Prospects for rare earth element mineralization in the weathering crusts developed on granite-gneisses of the Souktal Plutonic Complex (Northern Kazakhstan)

- 1 — Ph.D. Postdoctoral Scholar Nazarbayev University ▪ Orcid

- 2 — Ph.D. Associate Professor Nazarbayev University ▪ Orcid

- 3 — Junior Researcher Institute of Precambrian Geology and Geochronology RAS ▪ Orcid

- 4 — Ph.D. Senior Researcher N.A.Chinakal Institute of Mining Siberian Branch RAS ▪ Orcid

Abstract

This study investigates unique weathering crust samples from the most altered sections (30-43 m) of the weathering profile within the Souktal Plutonic Complex, Northern Kazakhstan. The samples, obtained from two drill cores, consist of quartz, kaolinite, microcline, muscovite, and plagioclase, as identified through polarized light microscopy and confirmed by X-ray diffraction analysis. Sequential extraction of rare earth elements (REE) was performed using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) following a two-step leaching procedure with hydroxylamine hydrochloride (0.2 mol NH2OH·HCl) and sodium hydroxide (1 mol NaOH) solutions. The extraction process effectively recovered REE, indicating their presence in an ion-exchangeable form, with total extraction rates (REE + Sc + Y) ranging from 4.1 to 7.8 ppm. The total light REE content varies from 3.5 to 5.9 ppm, while heavy REE content ranges from 0.2 to 0.7 ppm across all samples. Petrological and geochemical analyses suggest that the studied area represents an ion-adsorption-type REE weathered deposit. These findings enhance the understanding of ionic-adsorbed REE within weathering crusts and highlight the effectiveness of sequential extraction methods for REE determination. Moreover, the study suggests that this area holds promising potential as a future REE ion-adsorption site, contributing to the development of Kazakhstan’s national REE industry.

Funding

The work was performed within the framework of topic 064.01.00 (SPG) of Nazarbayev University and the research topic of the IPGG RAS FMUW 2025-0003 (FMUW 2022-0004).

Introduction

The interest in rare earth elements (REE) has been steadily increasing due to their crucial role in various industries, including electronics, aviation, automotive manufacturing, energy production, and many others. Despite their occurrence in various minerals, the average concentration of REE in the Earth’s crust is relatively low, and the number of known REE deposits remains limited [1, 2]. Rare earth elements play a vital role in modern industry and have significant potential for advancing new technologies and innovations. Hence, there is a growing emphasis on identifying sources of REE and improving their extraction and processing methods. REE play a crucial role in deciphering the genesis of various geological processes, including those at the mineral scale [3-5]. Recent studies have demonstrated that trace elements can be highly sensitive indicators of rare-metal mineralization [6, 7]. Thus, studying the distribution of rare and rare earth elements provides valuable data for identifying mineral deposits and analyzing their genesis. This method is applicable to both scientific research and practical applications in geosciences, including mineral exploration and extraction [8]. The primary sources of REE include minerals such as bastnasite, monazite, loparite, xenotime, and ion-adsorption clays [9].

Weathering processes lead to the leaching of REE from minerals, followed by their adsorption, resulting in the formation of ion-adsorption-type weathering crusts [10]. These deposits are widely distributed in Southern China and represent one of the world’s main sources of heavy rare earth elements (HREE) [11]. In addition to REE fractionation through the dissolution of REE-bearing minerals [12] other mechanisms of deposit formation include complexation with organic and inorganic ligands [13], mineral adsorption [14], surface precipitation [15], and redox reactions [16]. These characteristics make REE valuable indicators for studying the geochemical properties of rocks. Global REE reserves are estimated at approximately 120 million t, with the majority located in China, Brazil, Russia, India, and Australia. The most productive REE deposits are associated with carbonatites, alkaline rocks, and weathering crusts [17, 18].

Significant advancements in REE separation have been achieved through ion exchange [19, 20] and extraction methods [21]. Sequential chemical leaching or extraction is a highly effective technique for studying REE behavior [22, 23], widely applied in fractionating these elements in soils and sediments [24, 25].

Kazakhstan holds significant potential for REE deposit discoveries due to its substantial unexplored resources. The country has registered 384 deposits across 160 sites, including carbonatite, alkaline, magmatic, metamorphic, metasomatic, sedimentary, and weathering crust-type deposits [26]. One of the poorly studied weathering crust deposits is Souktal, located in the northern part of the country. Therefore, determining REE concentrations in the weathering crust over the Souktal granitic-gneisses using a two-stage sequential chemical extraction method is a relevant research objective.

Geological settings

The study area is located along the southeastern boundary of the Kostanay Region in Northern Kazakhstan. It lies within a tectonomagmatically reactivated zone at the junction of a regional submeridional compression zone and deep-seated fault structures of both sublatitudinal and submeri-dional orientations. These structures have contributed to the development of quartz-feldspar metasomatism with rare-metal (Sn, W, Be, Ta, Nb, etc.) and the formation of linear weathering crusts. Proterozoic granitic gneisses (γ2 PR2) represent the oldest rocks of the Souktal Massif. The massif ’s granitoids exhibit diverse compositions, though coarse-grained granitic gneisses predominate. These gneisses are encircled by a halo of banded microcline gneisses [27]. Proterozoic formations (PR) form the core of the Mesozoic Ulytau Anticline, where the exhumation and weathering of the Souktal granitic-gneiss complex have occurred [27]. The weathering crust over the granitic gneisses varies in thickness from 23 to 85 m [27]. The region also contains Lower to Middle Proterozoic (PR1-2) green schists and tuffs, with the total Proterozoic sequence reaching 5400-5700 m in thickness. The Proterozoic and Palaeozoic formations comprise the folded basement, while Mesozoic and Cenozoic unconsolidated deposits form the platform cover. Palaeozoic strata are relatively scarce. Devonian terrigenous sequences consist of red-coloured arkose sandstones, siltstones, coarse-grained sandstones, and conglomerates, with the upper portion characterized by interbedded fine-grained red sandstones, siltstones, and pinkish-gray calcareous sandstones (total thickness – 150 m). The Devonian strata exhibit a sharp angular unconformity with Palaeozoic mafic intrusions (gabbro) and Proterozoic schists [27].

The weathering profile is divided into four distinct zones: granitic-gneiss zone – characterized by fractures filled with manganese oxides and iron hydroxides; kaolinite-montmorillonite zone – composed of variegated clays, predominantly light green, greenish-light gray, gray, and black; reddish-gray kaolinite zone – consists of kaolinite, quartz, iron, and hydroxides; white kaolinite zone – primarily composed of kaolinite and quartz. Supergene formations are overlain by Cenozoic and Quaternary deposits. The sedimentary cover mainly consists of sands, loams, silts, and aeolian and alluvial deposits, reaching a thickness of up to 70 m [27].

Sampling and analytical methods

Sampling was conducted from two boreholes, labeled C-15 (N49°31'32.82"-E66°38'18.72") and C-18 (N49°31'32.84"-E66°38'24.30"), due to the lack of surface exposures. Borehole C-15 reached a depth of 43 m, while borehole C-18 extended to 30 m. Each collected sample weighed approximately 1 kg.

The mineral composition of the weathering crust was determined using a transmitted light microscope (Zeiss Primotech), for preliminary optical diagnostics and subsequently determined using X-ray diffraction (XRD). X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was performed using a Rigaku Smart Lab instrument with a CuKα X-ray source for samples at 30 kV X-ray tube voltage, 15 mA current, with a fixed slit system, a scanning range of 3 to 90°, a minimum step of 0.020 and a scanning speed of 2 rpm. Samples of the weathering crust from boreholes were carefully crushed, pulverized, and homogenized in a laboratory ball mill (Retsch, TM 300 DrumMill) at 80 rpm for 10-20 min, and then sieved using a sieve shaker (Retsch, AS 300 Control) to obtain powders with a particle size of 74 μm. 25 g of distilled water was added to 10 g of each sample, and the mixtures were left in sealed graduated cylinders at room temperature for two days to reach equilibrium. The pH of the resulting solutions was measured with a pH meter (ISOLAB). Subsequently, the samples were dried in an oven at 60 °C and ground in an agate mortar.

The two-step sequential leaching of REE in the samples was performed following the methods described in references [28, 29] as outlined:

- A 10 ml solution of NH2 OH·HCl (0.2 mol, pH = 5.0) was added to 1 g of powdered samples (74 μm) [30, 31] and shaken for 3 h. The suspension was then heated in a water bath at 95 °C for 4 h while being continuously mixed with a magnetic stirrer at 250 rpm. After centrifugation and filtration, the supernatant was collected.

- The residue was transferred into a glass beaker, and 10 ml of 1 mol NaOH was added. The mixture was then stirred at 350 rpm using a heating magnetic stirrer while being heated in a water bath at 75 °C for 1 h.

The liquid extracts from both steps were further analyzed for REE concentrations using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS). The concentrations of REE were determined using a single quadrupole-based ICP-MS (Thermo Fisher Scientific iCAP RQ). The calibration standard IV-STOCK-26-125ML was used to construct calibration curves and evaluate the reliability of the obtained results. The detection limits for all elements were calculated based on the calibration curves and were less than 0.0005 µg/l.

All analytical studies were conducted at Nazarbayev University (Astana, Kazakhstan).

Results

Mineral composition of rocks

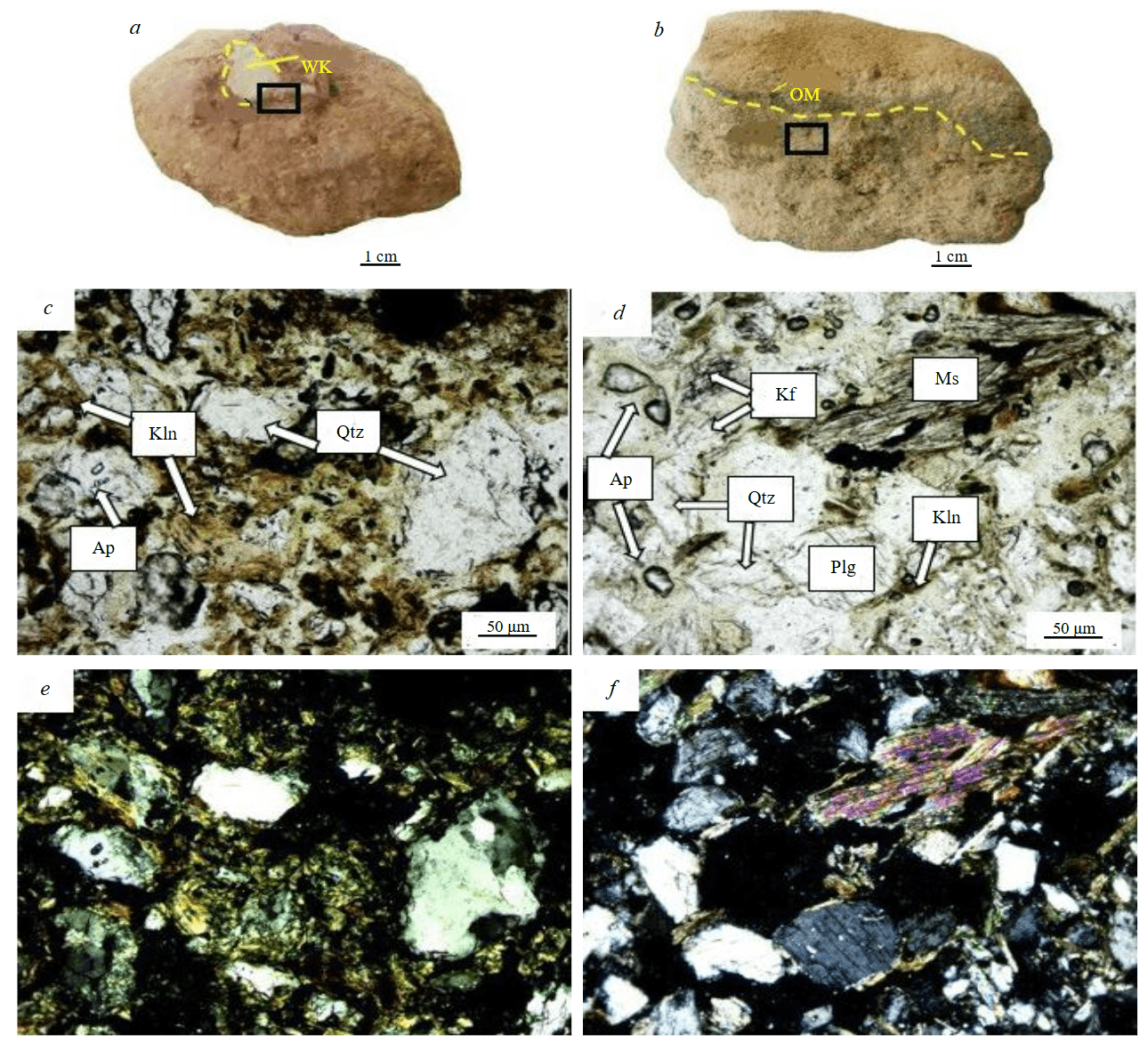

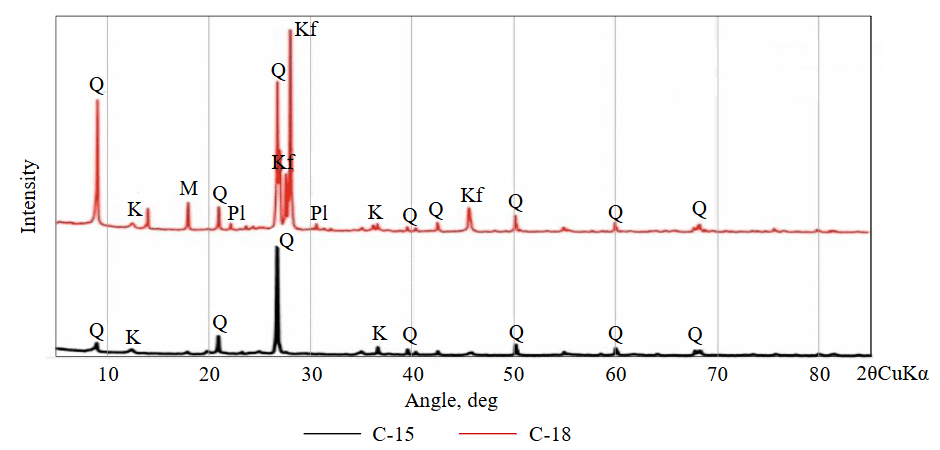

In hand specimens, the sample C-15 occurs as a slightly sticky reddish-brown, while the sample C-18 is yellowish brown, light and brittle. Both specimens are highly weathered granitic gneisses. The petrographic study revealed that they are composed of muscovite, K-feldspar, quartz, plagioclase, kaolinite, and Fe hydroxides (Fig.1). However, XRD patterns confirmed the presence of K-feldspar, quartz, plagioclase with minor muscovite and kaolinite but Fe hydroxides was never detected in XRD spectra (Fig.2). The average mineral contents show that the sample C-15 has, vol.%: 42.7 quartz, 54.3 kaolinite; and 3 hydroxides Fe; while sample C-18 has, vol.%: 47.8 quartz, 35 kaolinite, 8.3 K-feldspar, 5.4 muscovite, 3.5 plagioclase, and a small amount of amorphous materials.

Fig.1. Weathering crust fragments, sample C-15 – note-white kaolinite (WK) fragments in reddish brown fragile clay (a); sample C-18 – yellowish-grey fragile clay interbedded with organic matter (OM) (b); micrographs without analyzer (c, d); with analyzer (e, f ); quartz grains cemented by kaolinite with iron hydroxide (c, e); grains of quartz, feldspar, apatite, kaolinite and muscovite (d, f). Mineral abbreviations after R.Kretz [32]

Fig.2. X-ray diffraction (XRD) spectra of the samples: M – muscovite; Kf – K-feldspar; Q – quartz; K – kaolinite; Pl – plagioclase

Sequential experimental leaching

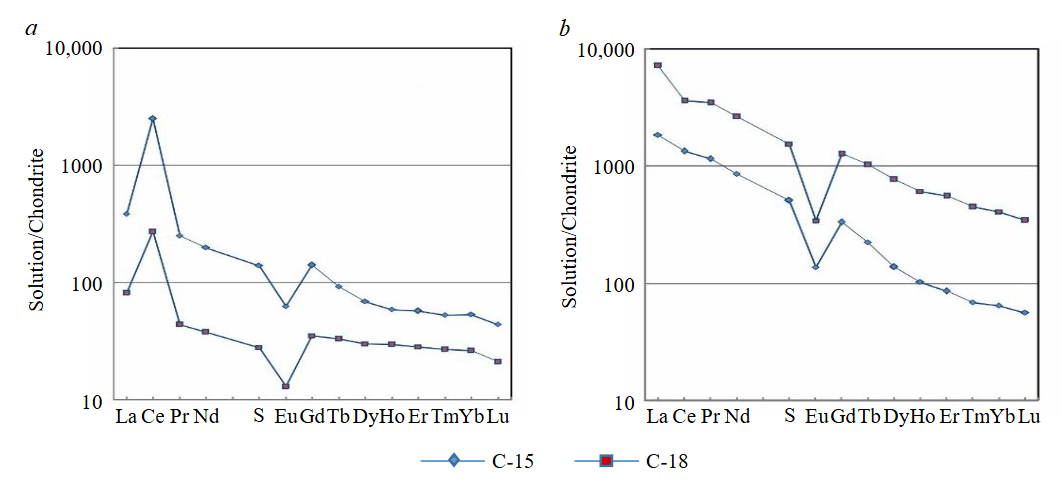

All REE, including Y and Sc, with the exception of Pm, were successfully extracted in the sequential leaching process (Fig.3).

Fig.3. Distribution of REE in experimental solutions at the first stage of leaching (a); at the second stage of leaching (b)

In the first step of the leaching, Ce, La, Nd, Y, Sc, Gd and Sm were extracted in relatively high amounts, while Eu, Tb, Dy, Ho, Er, Yb, and Tm were in much smaller quantities from the sample C-15 (see Table). On the other hand, sample C-18 released comparatively low amounts.

REE concentrations in the extracted solutions (ICP-MS)

|

Element |

Sample C-15 |

Sample C-18 |

|||

|

1st step NH2OH·HCl, ppb |

2nd step NaOH, ppb |

1st step NH2OH·HCl, ppb |

2nd stepNaOH, ppb |

||

|

Sc |

26.71 |

98.11 |

Below the detection limit |

146.32 |

|

|

Y |

59.16 |

116.88 |

38.32 |

1072.88 |

|

|

La |

90.27 |

435.86 |

19.16 |

1692.78 |

|

|

Ce |

1513.07 |

815.03 |

165.15 |

2214.96 |

|

|

Pr |

23.08 |

106.18 |

4.04 |

320.80 |

|

|

Nd |

90.50 |

391.20 |

17.22 |

1195.81 |

|

|

Sm |

20.64 |

75.11 |

4.13 |

227.78 |

|

|

Eu |

3.51 |

7.72 |

0.72 |

19.31 |

|

|

Gd |

27.88 |

65.88 |

7.02 |

251.70 |

|

|

Tb |

3.32 |

8.07 |

1.19 |

37.05 |

|

|

Dy |

16.89 |

33.81 |

7.40 |

188.67 |

|

|

Ho |

3.21 |

5.59 |

1.61 |

33.33 |

|

|

Er |

9.09 |

13.67 |

4.53 |

88.54 |

|

|

Tm |

1.30 |

1.69 |

0.66 |

11.04 |

|

|

Yb |

8.55 |

10.42 |

4.20 |

65.73 |

|

|

Lu |

1.07 |

1.38 |

0.52 |

8.48 |

|

|

ΣРЗЭ |

1812 |

1971 |

237 |

6351 |

|

|

La/Yb |

10.55 |

41.83 |

4.56 |

25.76 |

|

|

Ce/Ce* |

2.83 |

0.96 |

2.13 |

0.85 |

|

|

Σ sample, ppm |

1.8 |

2.3 |

0.2 |

6.3 |

|

|

Total Σ REE, ppm |

4.1 |

6.5 |

|||

|

ΣРЗЭ + Sc + Y |

4.1 |

7.8 |

|||

In the second leaching step (remnant of REE from the 1st step of extraction), the high concentration of Ce, La, Nd, Y, Pr, Sc, and Lu was leached in sample C-15; while sample C-18 liberated even higher quantity (see Table).

The most abundant extracted element is Ce in the 1st step leaching, followed by Nd and La, in C-15 whereas in C-18 the order is Ce > Y > La. In the 2nd step of leaching, the extracted amount is Ce > La > Nd > Y in both samples (see Table). Ce has the highest extracted values while Tm has the lowest.

The results of laboratory experiments showed that the obtained solutions are characterized by elevated values of light rare earth elements (LREE) relative to HREE. The La/Yb ratio in the experimental solutions at the first leaching stage was 10.5 and 4.6 in samples C-15 and C-18, respectively. The La/Yb ratio in C-15 and C-18 at the second leaching stage is higher, at 41.8 and 25.8. The total extraction of REE, including Sc and Y, during the two-stage sequential leaching was 4.1 ppm from sample C-15 and 7.8 ppm from sample C-18 (see Table).

The experimental solutions from the first leaching stage showed maximum Ce-anomaly values of 2.83 in the sample from borehole C-15 and 2.13 in the sample from borehole C-18. The minimum Ce/Ce* values were obtained at the second leaching stage – 0.96 and 0.85 from the samples of boreholes C-15 and C-18, respectively (see Table).

The results of laboratory experiments showed a negative Eu-anomaly at two stages of the experiment (Fig.3).

The pH measurements indicate a higher value of 5.03 in C-18 and a lower value of 4.85 in C-15.

Discussion

Origin of REE in ion-adsorption form in the weathering crust of granite-gneisses

The weathered granitic gneiss from the Souktal Plutonic Complex is characterized as a clay-rich REE deposit, where feldspars undergo kaolinization due to crustal weathering and deposition from detrital sedimentary rocks. Quartz, the most stable mineral, is present in all weathering crust zones. It is often leached, angular, and contains traces of mica with clay aggregates adhering to its surface, and occasionally has inclusions of black, iron-rich minerals [27]. Feldspars and platy-angular fragments of light and greenish micas are predominantly found in clay-mica zones, with feldspars being replaced by kaolinite. The minerals are frequently impregnated with iron and manganese hydroxides [27]. In both samples, kaolinite is closely associated with Fe hydroxides (see Fig.1). However, Fe hydroxides were not detected in the XRD spectra due to their amorphous or poorly crystalline state [33]. The results of the studies showed that the main minerals concentrating REE in the weathering crust are kaolinite, micas, iron hydroxides, feldspars, and apatite. Our results show that the REE in the Souktal are of a typical ion-adsorption origin. Ion-adsorption-type REE deposits refer to the phenomenon where REE bind to clay minerals and sediment particles through electrostatic attraction in their ionic form [34]. This type of deposit was first discovered in China (in 1969), in the weathered granitic crust in Longnan, Jiangxi Province [35, 36]. Later, similar deposits were subsequently found in other places. Several authors have attributed the formation of these deposits to the enrichment of REE through the weathering of magmatic parent rocks. The content of clay minerals in the weathering crusts of deposits ranges from 40 to 70 %, and the content of ion-exchangeable REE in samples typically ranges from 50 to 70 % [37-39].

REE-bearing minerals in rocks can be broadly classified into two categories: REE-bearing accessory and ore minerals (including silicates such as zircon, allanite, titanite, and garnet; phosphates such as xenotime, apatite, and monazite; fluoro-carbonates such as bastnasite, synchysite, and parisite; as well as niobates, tantalates, and fluorite) and rock-forming minerals (such as feldspar, quartz, muscovite, biotite, and amphibole, and others) [40-42]. Approximately 78 % of REE originate from the decomposition of REE-bearing minerals, while the breakdown of rock-forming minerals contributes around 22 % [12, 24]. The increase in REE concentrations is primarily driven by the decomposition of accessory minerals and the extent of mineral weathering within the weathering profile [24, 40]. In the weathering crust deposits of Northern Kazakhstan, cerium-group REE generally dominate over yttrium-group REE [43]. Although REE are relatively widespread, their distribution is highly uneven along both the strike and dip within the weathering profile [27]. In the weathering crust of the Souktal Massif, the primary REE- and Y-bearing minerals are kaolinite, muscovite, and, to a lesser extent, plagioclase [25].

Additionally, clay minerals act as indicators of the degree of rock weathering, with fully weathered layers primarily characterized by the transformation of feldspar into kaolinite [24, 44]. Within the weathering profile, as rock transitions to clay, REE are initially leached from the parent material and, with increasing pH, become adsorbed in the most intensely weathered horizons. The total extracted REE content is 6.5 ppm in sample C-18, whereas it is lower in sample C-15, at 4.1 ppm. These findings may help identify more enriched weathering crust zones within the study area.

The reliability of selected reagents for leaching

Primary REE-bearing minerals break down during weathering, thus releasing soluble REE ions [45]. These ions interact mainly with clay minerals and other sediments, forming ion-exchangeable complexes that can be easily leached or extracted [38, 39]. To enhance the efficiency of REE extraction, extensive research has been conducted on the extraction processes of REE from weathering crusts, which have formed because of leaching from parent rocks [46]. The extraction of REE ions adsorbed on clay minerals can be desorbed through ion exchange by cations, including Na+, Ca2+, and NH4 [20, 38, 47]. The results of two-stage leaching experiments on weathering crust samples from the granitic-gneisses of the Souktal Plutonic Complex in Northern Kazakhstan demonstrated successful REE extraction using NH2OH·HCl and NaOH. Therefore, the leaching procedure with these reagents is a reliable method for extracting ion-exchangeable REE.

Distribution characteristics of REE

The LREE (La, Ce, Pr, Nd, Sm, Eu, and Sc) are released at a rate five times higher than the HREE (Y, Tb, Dy, Ho, Er, Tm, Yb, Lu, and Gd) in both of the samples. A similar LREE-enriched mineral deposit has been observed in the granite porphyry of the Jiangxi Region, China [48]. A key indicator of chemical weathering is the enrichment of REE in the weathering crust relative to the parent substrate [49]. In weathering crusts formed on granitoid protoliths, HREE are generally more enriched [50]. However, this study demonstrates that LREE dominate in solution after leaching, with La/Yb ratios of 10.5 and 4.6 in samples C-15 and C-18, respectively, during the first leaching stage, and increasing to 41.8 and 25.8 in samples C-15 and C-18 in the second leaching stage (see Table). Research conducted at the Institute of Precambrian Geology and Geochronology of the RAS confirms the preferential removal of LREE from the weathering profile during the leaching of Precambrian granitoids from the Fennoscandian Shield. Furthermore, the study revealed that when weakly acidic sulfuric acid interacts with Paleoproterozoic granitic gneisses of the Fennoscandian Shield, progressive LREE enrichment relative to HREE occurs with increasing interaction time [51]. Similar findings have been reported in previous studies on the selective leaching of REE from marine sediments using hydrochloric acid [52].

Among REE, europium can exist in multiple oxidation states. A negative Eu-anomaly (Fig.3) is characteristic of highly weathered rocks, where Eu3+ is leached under oxidizing conditions [52].

Cerium can exist as Ce3+ and Ce4+ under supergene conditions. The presence of Ce in both forms within modern natural aquatic systems is evident, as indicated by a negative Ce-anomaly in oxygenated waters. In contrast, anoxic waters exhibit a positive Ce-anomaly, indicating Ce enrichment relative to La and Nd (including Pd). Since the pH of oceanic water remains relatively stable and can be measured or calculated, the partial oxygen pressure can be determined based on Ce content. However, in the drainage solutions of the supergene zone, pH values are more variable and fluctuate across different stages of continental weathering [51, 52]. Numerous factors influence Ce behaviour [13, 53, 54], with pH-Eh conditions being the primary controls on Ce partitioning between solid and liquid phases [55]. Another key factor affecting Ce behaviour is the intensity of drainage within the weathering profile [52]. Our results indicate that the Ce-anomaly is positive during the first leaching stage but becomes negative in the second stage, likely due to variations in pH conditions. Additionally, Ce exhibits a relatively high concentration among REE (Fig.3). During the first leaching stage, a positive Ce-anomaly is observed, whereas the second, alkaline leaching stage results in a negative Ce-anomaly. Petrographic studies reveal that Fe hydroxides are closely associated with kaolinite (see Fig.1). Previous research [45, 56, 57] has shown that Fe hydroxides play a critical role in forming positive Ce-anomalies across various geological settings. These Fe hydroxides account for approximately 95 % of the total Ce content, as Fe oxides can adsorb REE and are typically associated with clay minerals [50, 52]. Studies on REE sorption and co-precipitation onto Fe hydroxides have demonstrated a positive Ce-anomaly in solutions due to its oxidation in the solid phase [50]. These findings align with our data, which show positive Ce-anomalies (Ce/Ce* = 2.83 and 2.3) during the first leaching stage.

Conclusion

Petrographic and geochemical analyses suggest that the weathering profile of the Souktal Massif holds significant potential for further REE exploration. The findings confirm that the deposit belongs to the ion-adsorption type of REE deposits formed in the weathering crust of granitic-gneisses. Sequential leaching effectively extracted REE, with total recovery of REE + Sc + Y ranging from 4.1 to 7.8 ppm. The total content of LREE varies from 3.5 to 5.9 ppm, while HREE range from 0.2 to 0.7 ppm. The observed positive Ce-anomaly in the weathering profile is attributed to the association of kaolinite with Fe hydroxides. Based on these results, further investigations are recommended to a depth of approximately 100 m.

These findings not only enhance our understanding of geological processes in the formation of ion-adsorption deposits but also hold practical significance for the industrial development of REE resources in the region.

References

- Binnemans K., Jones P.T. Rare Earths and the Balance Problem. Journal of Sustainable Metallurgy. 2015. Vol. 1. Iss. 1, p. 29-38. DOI: 10.1007/s40831-014-0005-1

- Takeda O., Okabe T.H. Current Status on Resource and Recycling Technology for Rare Earths. Metallurgical and Materials Transactions E. 2014. Vol. 1. Iss. 2, p. 160-173. DOI: 10.1007/s40553-014-0016-7

- Rogova I.V., Stativko V.S., Petrov D.A., Skublov S.G. Trace Element Composition of Zircons from Rapakivi Granites of the Gubanov Intrusion, the Wiborg Massif, as a Reflection of the Fluid Saturation of the Melt. Geochemistry International. 2024. Vol. 62. N 11, p. 1123-1136. DOI: 10.1134/S0016702924700630

- Skublov S.G., Petrov D.A., Galankina O.L. et al. Th-Rich Zircon from a Pegmatite Vein Hosted in the Wiborg Rapakivi Granite Massif. Geosciences. 2023. Vol. 13. Iss. 12. N 362. DOI: 10.3390/geosciences13120362

- Salimgaraeva L., Berezin A., Sergeev S. et al. Zircons from Eclogite-Associated Rocks of the Marun–Keu Complex, the Polar Urals: Trace Elements and U–Pb Dating. Geosciences. 2024. Vol. 14. Iss. 8. N 206. DOI: 10.3390/geosciences14080206

- Skublov S.G., Hamdard N., Ivanov M.A., Stativko V.S. Trace element zoning of colorless beryl from spodumene pegmatites of Pashki deposit (Nuristan province, Afghanistan). Frontiers in Earth Science. 2024. Vol. 12. N 1432222. DOI: 10.3389/feart.2024.1432222

- Levashova E.V., Skublov S.G., Hamdard N. et al. Geochemistry of Zircon from Pegmatite-bearing Leucogranites of the Laghman Complex, Nuristan Province, Afghanistan. Russian Journal of Earth Sciences. 2024. Vol. 2. Iss. 2. N ES2011 (in Russian). DOI: 10.2205/2024ES000916

- Evdokimov A.N., Pharoe B.L. Indicator role of rare and rare-earth elements of the Northwest manganese ore occurrence (South Africa) in the genetic model of supergene manganese deposits. Journal of Mining Institute. 2021. Vol. 252, p. 814-825. DOI: 10.31897/PMI.2021.6.4

- Shijie Wang. Rare Earth Metals: Resourcefulness and Recovery. JOM. 2013. Vol. 65. Iss. 10, p. 1317-1320. DOI: 10.1007/s11837-013-0732-y

- Yan Hei Martin Li, Wen Winston Zhao, Mei-Fu Zhou. Nature of parent rocks, mineralization styles and ore genesis of reg-olith-hosted REE deposits in South China: An integrated genetic model. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences. 2017. Vol. 148, p. 65-95. DOI: 10.1016/j.jseaes.2017.08.004

- Zhiwei Bao, Zhenhua Zhao. Geochemistry of mineralization with exchangeable REY in the weathering crusts of granitic rocks in South China. Ore Geology Reviews. 2008. Vol. 33. Iss. 3-4, p. 519-535. DOI: 10.1016/j.oregeorev.2007.03.005

- Bosia C., Chabaux F., Pelt E. et al. U–Th–Ra variations in Himalayan river sediments (Gandak river, India): Weathering frac-tionation and/or grain-size sorting? Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 2016. Vol. 193, p. 176-196. DOI: 10.1016/j.gca.2016.08.026

- Davranche M., Pourret O., Gruau G., Dia A. Impact of humate complexation on the adsorption of REE onto Fe oxyhydroxide. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science. 2004. Vol. 277. Iss. 2, p. 271-279. DOI: 10.1016/j.jcis.2004.04.007

- Piasecki W., Sverjensky D.A. Speciation of adsorbed yttrium and rare earth elements on oxide surfaces. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 2008. Vol. 72. Iss. 16, p. 3964-3979. DOI: 10.1016/j.gca.2008.05.049

- Dardenne K., Schäfer T., Lindqvist-Reis P. et al. Low Temperature XAFS Investigation on the Lutetium Binding Changes during the 2-Line Ferrihydrite Alteration Process. Environmental Science & Technology. 2002. Vol. 36. Iss. 23, p. 5092-5099. DOI: 10.1021/es025513f

- Bau M., Koschinsky A. Oxidative scavenging of cerium on hydrous Fe oxide: Evidence from the distribution of rare earth elements and yttrium between Fe oxides and Mn oxides in hydrogenetic ferromanganese crusts. Geochemical Journal. 2009. Vol. 43. Iss. 1, p. 37-47. DOI: 10.2343/geochemj.1.0005

- Tkachev A.V., Rundqvist D.V., Vishnevskaya N.A. Main Features of the REE Metallogeny through Geological Time. Geology of Ore Deposits. 2022. Vol. 64. N 3, p. 41-77. DOI: 10.1134/S1075701522030060

- Yufeng Huang, Hongping He, Xiaoliang Liang et al. Characteristics and genesis of ion adsorption type REE deposits in the weathering crusts of metamorphic rocks in Ningdu, Ganzhou, China. Ore Geology Reviews. 2021. Vol. 135. N 104173. DOI: 10.1016/j.oregeorev.2021.104173

- Spedding F.H., Voigt A.F., Gladrow E.M, Sleight N.R. The Separation of Rare Earths by Ion Exchange. I. Cerium and Yttrium. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1947. Vol. 69. Iss. 11, p. 2777-2781. DOI: 10.1021/ja01203a058

- Spedding F.H., Voigt A.F., Gladrow E.M. et al. The Separation of Rare Earths by Ion Exchange. II. Neodymium and Praseodymium. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1947. Vol. 69. Iss. 11, p. 2786-2792. DOI: 10.1021/ja01203a060

- Zimina G.V., Nikolaeva I.I., Tauk M.V., Tsygankova M.V. Extraction schemes of rare-earth metals’ separation. Tsvetnye metally. 2015. N 4, p. 23-27 (in Russian). DOI: 10.17580/tsm.2015.04.04

- Land M., Öhlander B., Ingri J., Thunberg J. Solid speciation and fractionation of rare earth elements in a spodosol profile from northern Sweden as revealed by sequential extraction. Chemical Geology. 1999. Vol. 160. Iss. 1-2, p. 121-138. DOI: 10.1016/S0009-2541(99)00064-9

- Estrade G., Marquis E., Smith M. et al. REE concentration processes in ion adsorption deposits: Evidence from the Ambohimirahavavy alkaline complex in Madagascar. Ore Geology Reviews. 2019. Vol. 112. N 103027. DOI: 10.1016/j.oregeorev.2019.103027

- Denys A., Janots E., Auzende A.-L. et al. Evaluation of selectivity of sequential extraction procedure applied to REE speciation in laterite. Chemical Geology. 2021. Vol. 559. N 119954. DOI: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2020.119954

- Zhenxiao Wu, Yu Chen, Yang Wang et al. Review of rare earth element (REE) adsorption on and desorption from clay minerals: Application to formation and mining of ion-adsorption REE deposits. Ore Geology Reviews. 2023. Vol. 157. N 105446. DOI: 10.1016/j.oregeorev.2023.105446

- Mihalasky M.J., Tucker R.D., Renaud K., Verstraeten I.M. Rare earth element and rare metal inventory of central Asia: Fact Sheet 2017–3089. U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey, 2018, p. 4. DOI: 10.3133/fs20173089

- Isayeva L.D., Dyussembayeva K.Sh., Kembayev M.K., Yusupova U. Rare earth elements and their forms of occurrence in the weathering crust of ore talayryk (the North Kazakhstan). News of the National Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Kazakhstan. Series of geology and technical sciences. 2015. Vol. 6. N 414, p. 57-65 (in Russian).

- Setiawan I. The sequential REE (Rare Earth Elements) extraction of weathered crusts of granitoids from Sibolga, Indonesia. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 2021. Vol. 882. N 012020. DOI: 10.1088/1755-1315/882/1/012020

- Junussov M., Mádai F., Földessy J., Hámor-Vidó M. The Role of Organic Matter in Gold Occurrence: Insights from Western Mecsek Uranium Ore Deposit. Economic and Environmental Geology. 2024. Vol. 57. Iss. 4, p. 371-386. DOI: 10.9719/EEG.2024.57.4.371

- Junussov M., Mustapayeva S. Preliminary XRF Analysis of Coal Ash from Jurassic and Carboniferous Coals at Five Kazakh Mines: Industrial and Environmental Comparisons. Applied Sciences. 2024. Vol. 14. Iss. 22. N 10586. DOI: 10.3390/app142210586

- Junussov M., Madai F., Kristály F. et al. Preliminary analysis on roles of metal–organic compounds in the formation of in-visible gold. Acta Geochimica. 2021. Vol. 40. Iss. 6, p. 1050-1072. DOI: 10.1007/s11631-021-00494-y

- Kretz R. Symbols for rock-forming minerals. American Mineralogist. 1983. Vol. 68. N 1-2, p. 277-279.

- Shi-Yong Wei, Fan Liu, Xiong-Han Feng et al. Formation and Transformation of Iron Oxide–Kaolinite Associations in the Presence of Iron(II). Soil Science Society of America Journal. 2011. Vol. 75. Iss. 1, p. 45-55. DOI: 10.2136/sssaj2010.0175

- Sababa E., Essomba Owona L.G., Temga J.P., Ndjigui P.-D. Petrology of weathering materials developed on granites in Biou area, North-Cameroon: implication for rare-earth elements (REE) exploration in semi-arid regions. Heliyon. 2021. Vol. 7. Iss. 12. N e08581. DOI: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e08581

- Deng-hong Wang, Zhi Zhao, Yang Yu et al. Exploration and research progress on ion-adsorption type REE deposit in South China. China Geology. 2018. Vol. 1. Iss. 3, p. 415-424. DOI: 10.31035/cg2018022

- Wang Zhen, Chen Zhen Yu, Zhao Zhi et al. REE mineral and geochemical characteristics of Neoproterozoic metamorphic rocks in South Jiangxi Province. Mineral Deposits. 2019. Vol. 38. N 4, p. 837-850 (in Chinese). DOI: 10.16111/j.0258-7106.2019.04.010

- Sanematsu K., Kon Y. Geochemical characteristics determined by multiple extraction from ion-adsorption type REE ores in Dingnan County of Jiangxi Province, South China. Bulletin of the Geological Survey of Japan. 2013. Vol. 64. N 11/12, p. 313-330.

- Li M.Y.H., Mei-Fu Zhou, Williams-Jones A.E. The Genesis of Regolith-Hosted Heavy Rare Earth Element Deposits: Insights from the World-Class Zudong Deposit in Jiangxi Province, South China. Economic Geology. 2019. Vol. 114. N 3, p. 541-568. DOI: 10.5382/econgeo.4642

- Li M.Y.H., Mei-Fu Zhou. The role of clay minerals in formation of the regolith-hosted heavy rare earth element deposits. American Mineralogist. 2020. Vol. 105. N 1, p. 92-108. DOI: 10.2138/am-2020-7061

- Yuejun Wang, Weiming Fan, Guowei Zhang, Yanhua Zhang. Phanerozoic tectonics of the South China Block: Key obser-vations and controversies. Gondwana Research. 2013. Vol. 23. Iss. 4, p. 1273-1305. DOI: 10.1016/j.gr.2012.02.019

- Bern C.R., Shah A.K., Benzel W.M., Lowers H.A. The distribution and composition of REE-bearing minerals in placers of the Atlantic and Gulf coastal plains, USA. Journal Geochemical Exploration. 2016. Vol. 162, p. 50-61. DOI: 10.1016/j.gexplo.2015.12.011

- Xiangping Zhu, Bin Zhang, Guotao Ma et al. Mineralization of ion-adsorption type rare earth deposits in Western Yunnan, China. Ore Geology Reviews. 2022. Vol. 148. N 104984. DOI: 10.1016/j.oregeorev.2022.104984

- Isayeva L.D., Dyussembayeva K.Sh., Kembayev M.K. et al. Forms of occurrence of rare earth elements in the weathering crust of the Kundybay deposit (North Kazakhstan). News of the National Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Kazakhstan. Series of geology and technical sciences. 2015. Vol. 2. N 410, p. 23-30 (in Russian).

- Alshameri A., Hongping He, Chen Xin et al. Understanding the role of natural clay minerals as effective adsorbents and al-ternative source of rare earth elements: Adsorption operative parameters. Hydrometallurgy. 2019. Vol. 185, p. 149-161. DOI: 10.1016/j.hydromet.2019.02.016

- Meijun Yang, Xiaoliang Liang, Lingya Ma et al. Adsorption of REEs on kaolinite and halloysite: A link to the REE distribution on clays in the weathering crust of granite. Chemical Geology. 2019. Vol. 525, p. 210-217. DOI: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2019.07.024

- Zhenyue Zhang, Changyu Zhou, Wendou Chen et al. Effects of Ammonium Salts on Rare Earth Leaching Process of Weath-ered Crust Elution-Deposited Rare Earth Ores. Metals. 2023. Vol. 13. Iss. 6. N 1112. DOI: 10.3390/met13061112

- Lifen Yang, Cuicui Li, Dashan Wang et al. Leaching ion adsorption rare earth by aluminum sulfate for increasing efficiency and lowering the environmental impact. Journal of Rare Earths. 2019. Vol. 37. Iss. 4, p. 429-436. DOI: 10.1016/j.jre.2018.08.012

- Zhi Zhao, Denghong Wang, Leon Bagas, Zhenyu Chen. Geochemical and REE mineralogical characteristics of the Zhaibei Granite in Jiangxi Province, southern China, and a model for the genesis of ion-adsorption REE deposits. Ore Geology Reviews. 2022. Vol. 140. N 104579. DOI: 10.1016/j.oregeorev.2021.104579

- Nesbitt H.W. Chapter 6 – Diagenesis and metasomatism of weathering profiles, with emphasis on Precambrian paleosols. Developments in Earth Surface Processes. Elsevier, 1992. Vol. 2: Weathering, Soils & Paleosols, p. 127-152. DOI: 10.1016/B978-0-444-89198-3.50011-8

- Chaoxi Fan, Cheng Xu, Aiguo Shi et al. Origin of heavy rare earth elements in highly fractionated peraluminous granites. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 2023. Vol. 343, p. 371-383. DOI: 10.1016/j.gca.2022.12.019

- Felitsyn S.B., Alfimova N.A., Klimova E.V. Fractionation of Rare Earth Elements in the Acid Treatment of Granitoids. Lithology and Mineral Resources. 2011. Vol. 46. N 4, p. 391-394. DOI: 10.1134/S0024490211040031

- Dubinin A.V. Geochemistry of rare earth elements in the ocean. Мoscow: Nauka, 2006, p. 360.

- Developments in Geochemistry. Ed. by P.Henderson. Elsevier, 1984. Vol. 2: Rare Earth Element Geochemistry, p. 522.

- Matrenichev V.A., Klimova E.V. Experimental modeling of the conditions for the formation of Precambrian weathering profiles. Composition of solutions and redistribution of lanthanides. Vestnik of Saint-Petersburg University. Earth Sciences. 2017. Vol. 62. N 4, p. 389-408 (in Russian). DOI: 10.21638/11701/spbu07.2017.405

- De Baar H.J.W., Bacon M.P., Brewer P.G., Bruland K.W. Rare earth elements in the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 1985. Vol. 49. Iss. 9, p. 1943-1959. DOI: 10.1016/0016-7037(85)90089-4

- Li M.Y.H., Mei-Fu Zhou, Williams-Jones A.E. Controls on the Dynamics of Rare Earth Elements During Subtropical Hillslope Processes and Formation of Regolith-Hosted Deposits. Economic Geology. 2020. Vol. 115. N 5, p. 1097-1118. DOI: 10.5382/econgeo.4727

- Ni Su, Shouye Yang, Yulong Guo et al. Revisit of rare earth element fractionation during chemical weathering and river sediment transport. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems. 2017. Vol. 18. Iss. 3, p. 935-955. DOI: 10.1002/2016GC006659