Physical properties of Paleozoic-Mesozoic deposits from wells in the South Barents Basin

- 1 — Ph.D. Senior Researcher Geological Institute of the KSC RAS ▪ Orcid

- 2 — Ph.D. Head of Department Apatity Branch of Murmansk Arctic University ▪ Orcid

Abstract

The Arctic shelf zone is an important research target due to its significant hydrocarbon potential. A study of the physical properties (density, elasticity, elastic anisotropy index, specific acoustic impedance, and porosity) was conducted for core samples from six wells in the South Barents Basin: Admiralteyskaya-1, Krestovaya-1, Ludlovskaya-1, Shtokmanskaya-1, Arkticheskaya-1, and Severo-Kildinskaya-82. The sample collection consists of sandstones, siltstones, and limestones. Core analysis revealed that rocks from non-productive wells (Arkticheskaya-1, Admiralteyskaya-1, and Krestovaya-1), located in the central part of the South Barents Basin and within the Admiralty High, differ in their physical and petrographic properties from rocks in gas and gas-condensate wells (Shtokmanskaya-1, Severo-Kildinskaya-82, and Ludlovskaya-1), located near the boundaries of the South Barents Basin. Core samples from productive wells (Shtokmanskaya-1, Severo-Kildinskaya-82, Ludlovskaya-1) exhibit lower average P-wave velocities, lower specific acoustic impedance, and higher open porosity and/or elastic anisotropy index compared to non-productive wells (Arkticheskaya-1, Admiralteyskaya-1, Krestovaya-1). This combination of petrophysical parameters provides the reservoir properties of rocks prospective for hydrocarbons. The petrographic variation of the reservoir properties of the studied rocks from productive to non-productive wells is associated with a decrease in grain size and a transition from pore-filling cement to thin-film and basal cement. The sandstones from the Shtokmanskaya well have a larger grain size (0.1-0.5 mm), whereas the sandstones from the Arkticheskaya-1 and Krestovaya-1 wells are finer-grained (0.1-0.2 mm). The Shtokmanskaya-1 well is characterized by pore-filling cement, the Arkticheskaya-1 ‒ by thin-film cement, and the Krestovaya-1 ‒ by cement of the basal type. The established physical properties of sedimentary rocks, suitable for the development of productive strata, will allow for the screening out of empty areas at the preliminary stage of analyzing geophysical materials during the search for geological and tectonic structures prospective for hydrocarbon accumulations.

Funding

The work was carried out in the framework of the State contract of GI KSC RAS N FMEZ-2024-0006.

Introduction

The importance of hydrocarbon resources today can hardly be overestimated. The Russian Federation holds approximately one-third of the world's natural gas reserves. In terms of oil reserves, Russia is second only to five countries, which is sufficient reason to develop this industry. According to some estimates, up to 30 % of the world's gas and 13 % of oil may be located on the shelves of the Eastern Arctic marginal seas at depths not exceeding 500 m [1]. The search, exploration, and development of these accumulations in the Arctic regions are associated with solving complex technical and technological challenges [2, 3]. The depletion of the hydrocarbon resource base under modern conditions necessitates the creation of new effective and environmentally friendly technologies for developing fields with hard-to-recover reserves, primarily those with low-permeability reservoirs [4, 5].

A major achievement was the discovery of the global Arctic Petroleum Belt. Geological exploration on the shelves of the Barents, Pechora, and Kara seas has mapped numerous local features and identified 22 hydrocarbon fields [6]. Oil, gas, and gas-condensate fields have been discovered in the Barents Sea. Oil fields (Varandey-more, Prirazlomnoye, etc.) have been found in its southeastern part (Pechora Sea), directly adjacent to the Timan-Pechora Basin. Five fields have been discovered in the South Barents Basin – the Shtokmanskoye and Ledovoye (gas-condensate), and the Severo-Kildinskoye, Murmanskoye, and Ludlovskoye (gas) [7]. Within the boundaries of the Barents Sea, coal deposits have been found (Timan-Pechora Basin, Svalbard Archipelago), coal-bearing strata [8] and rare earth element deposits [9] are known on Franz Josef Land. A substantial amount of drilling and geophysical data has been accumulated over a vast area, enabling the integrated interpretation of results from regional seismic exploration and the re-interpretation of archival seismic data to delineate and identify prospective zones of oil and gas accumulation and targets for further geological exploration in areas with ambiguous forecasts and a lack of commercial petroleum potential [10].

The South Barents and North Barents basins are unique areas of crustal subsidence with geological features favorable for the formation of large oil and gas accumulations: an enormous thickness of the sedimentary cover, rifted geodynamic conditions, and a wide range of rocks that can act as both fluid seals and reservoirs [11]. The South Barents gas-condensate and gas fields are directly associated with Triassic and Jurassic deposits and are confined to the peripheral and boundary zones of the basin [12].

Fundamental studies of the physical properties of rocks (core samples) from shelf deposits and geothermal investigations of marine muds in the Barents-Kara region have been conducted at the Geological Institute of the KSC RAS for many years [13-15]. With modern drilling and oil and gas production technologies, core studies are not always performed [7]. Nevertheless, it is core analysis that provides information on the reservoir properties of rocks, which is one of the key issues in identifying prospective structures and petroleum objects. Core material is used in experimental and theoretical studies of applicability of the method of directional reservoir depressurization in fields with low-permeability reservoirs [3], of efficiency of water-gas injection for condensate recovery from low-pressure reservoirs [16], of overburden pressure influence on the permeability of sandstones and other hydrocarbon reservoirs [17, 18], and estimating the compressibility coefficients of fractures and intergranular pores in hydrocarbon reservoirs [19]. Digital models also rely on a large number of parameters obtained from lithological and petrographic studies of thin sections and well cores [20].

An important aspect of well core studies is research into the changes in the physical properties of rocks during the retrieval of samples from great depths [21] and specifically, changes in the mechanical properties, porosity, and fracturing of reservoir rocks during core retrieval from depth to the surface [22, 23]. The use of refined data on the mechanical properties of retrieved rock samples enhances the accuracy of digital geological models, which are necessary for conducting geological exploration, determining reservoir properties, assessing oil and gas saturation of fields, and developing oil and gas deposits.

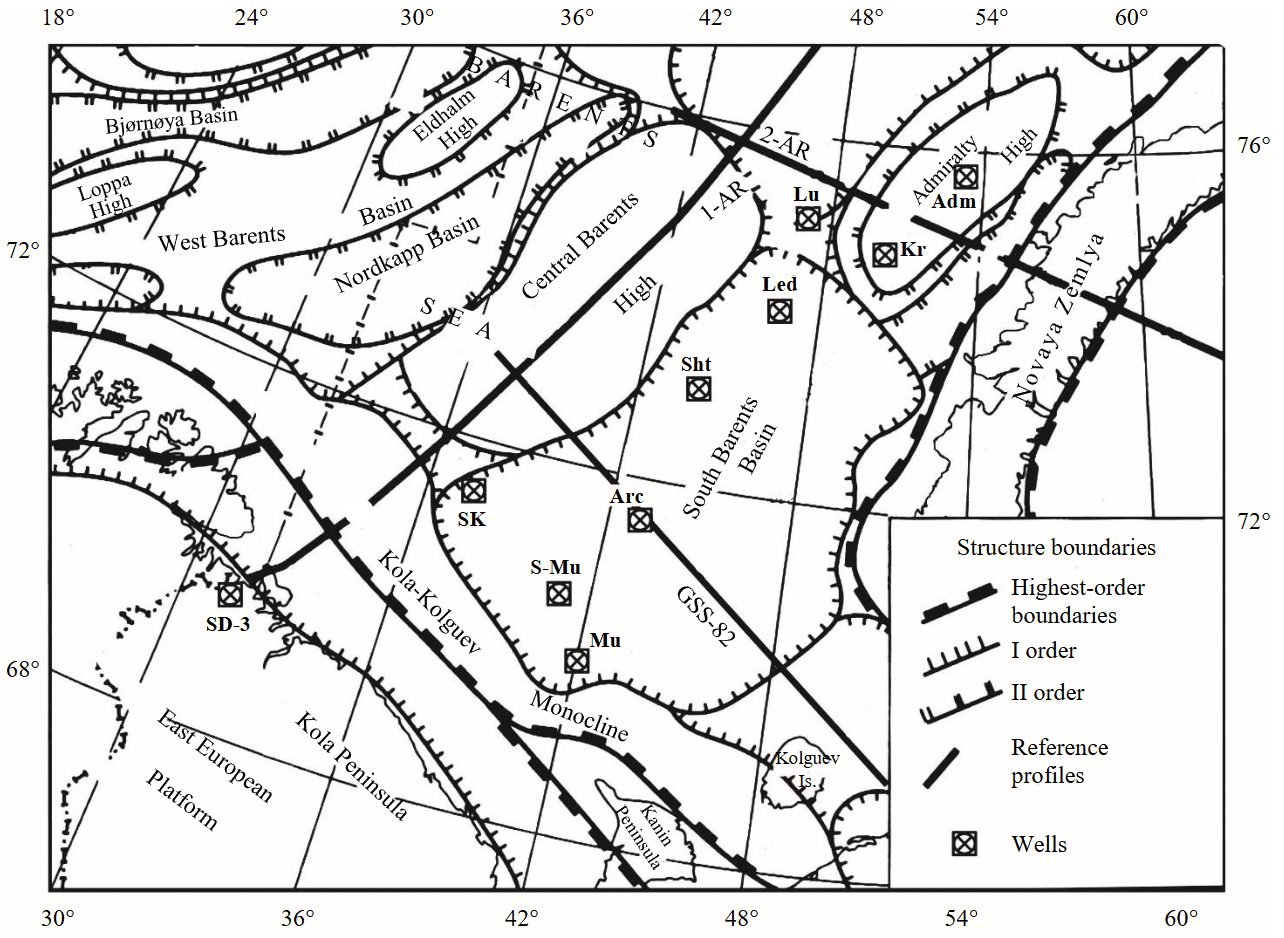

This paper presents a petrographic characterization and the results of a study of the physical properties of core (density, elasticity, elastic anisotropy index, specific acoustic impedance, and porosity) from wells in the South Barents Basin: Admiralteyskaya-1, Krestovaya-1, Ludlovskaya-1, Shtokmanskaya-1, Arkticheskaya-1, Severo-Kildinskaya-82 (Fig.1). The rocks are represented by Paleozoic-Mesozoic deposits of the interval from the Lower Permian to the Lower Cretaceous.

The value of the open porosity index serves as the primary criterion for the reservoir properties of sedimentary rocks. In this work, we examine which combinations of physical parameters can be characteristic of reservoir rocks. Information on the physical properties of sedimentary rocks from the shelf deposits of the South Barents Basin (and indeed from all offshore wells, in principle) appears infrequently in open publications, and this material may be useful for lithologists, petroleum geologists, marine geologists, and engineers.

Fig.1. Geological schematic map of the southern part of the Barents Sea [24] with location of wells: SD-3 – Kola Superdeep; SK – Severo-Kildinskaya-82; S-Mu – Severo-Murmanskaya; Mu – Murmanskaya-24; Аrc – Arkticheskaya-1; Led – Ledovaya-1; Кr – Krestovaya-1; Sht – Shtokmanskaya-1; Lu – Ludlovskaya-1; Аdm – Admiralteyskaya-1. Reference seismological profiles: GSS-82, 1-АR, 2-АR

Methods

Core samples (42 specimens) were studied in petrographic thin sections using POLAM RP-1 (“LOMO” JSC) and Amplival (Carl Zeiss Jena) polarizing microscopes. The methodologies of V.N.Shvanov and V.T.Frolov [25] were used for sandstone classification and determination of their granulometric composition, specifically V.N.Shvanov's diagram for sandy rocks, which considers the ratio of different clastic components (quartz, feldspars, rock fragments) in sandstones. Grain size was determined using an eyepiece with a scale ruler on the polarizing microscope.

The material for petrophysical studies was prepared as follows: cube-shaped samples (edge length 25-30 mm) were cut from the core, with their faces (wave propagation directions) marked as x, y, z; the normal to face z coincides with the core axis, while directions x and y are arbitrary and mutually orthogonal. Elastic properties (longitudinal wave velocities Vx, Vy, Vz) were measured in the three respective directions in dry samples using a standard GSP UK-10PMS ultrasonic device. The instrumental error of the time interval was ±0.5 %, the duration of a single measurement – 0.5 min, the operating frequency – 45-60 kHz. A concentrated polysaccharide solution was used as a coupling agent to ensure wave transmission from the sensor to the sample surface. The number of measurements in each of the three directions of a cubic sample ranged from 5 to 10.

Subsequently, the elastic anisotropy index was calculated using the formula

where Vm is the average propagation velocity of longitudinal waves, Vm = (Vx + Vy + Vz)/3.

The anisotropy of the elastic properties of a rock is determined by the geometry of its fracture system and, like permeability anisotropy, is one of the key petrophysical parameters important for reservoir rocks.

Density ρ was determined by hydrostatic weighing of the samples (Archimedes' method) in air-dry and water-immersed states, using the formula ρ = ρwmdry/(mdry – mwet), where ρw = 1 g/cm3 is the density of water; mdry is the weight of the dry sample in air; mwet is the weight of the sample immersed in water.

Specific acoustic impedance was determined by the formula R = ρVm. Variations in the R parameter indicate the alternation of rock layers with different physical properties in the section.

The open porosity coefficient was determined for each sample in the collection by impregnating initially dry core samples with kerosene. The porosity coefficient was calculated using the formula Cp = (Vpor/Vsample)∙100 %, where Vpor is the pore volume, cm3; Vsample – the sample volume, cm3. Porosity is one of the primary factors controlling reservoir quality [26, 27].

Results

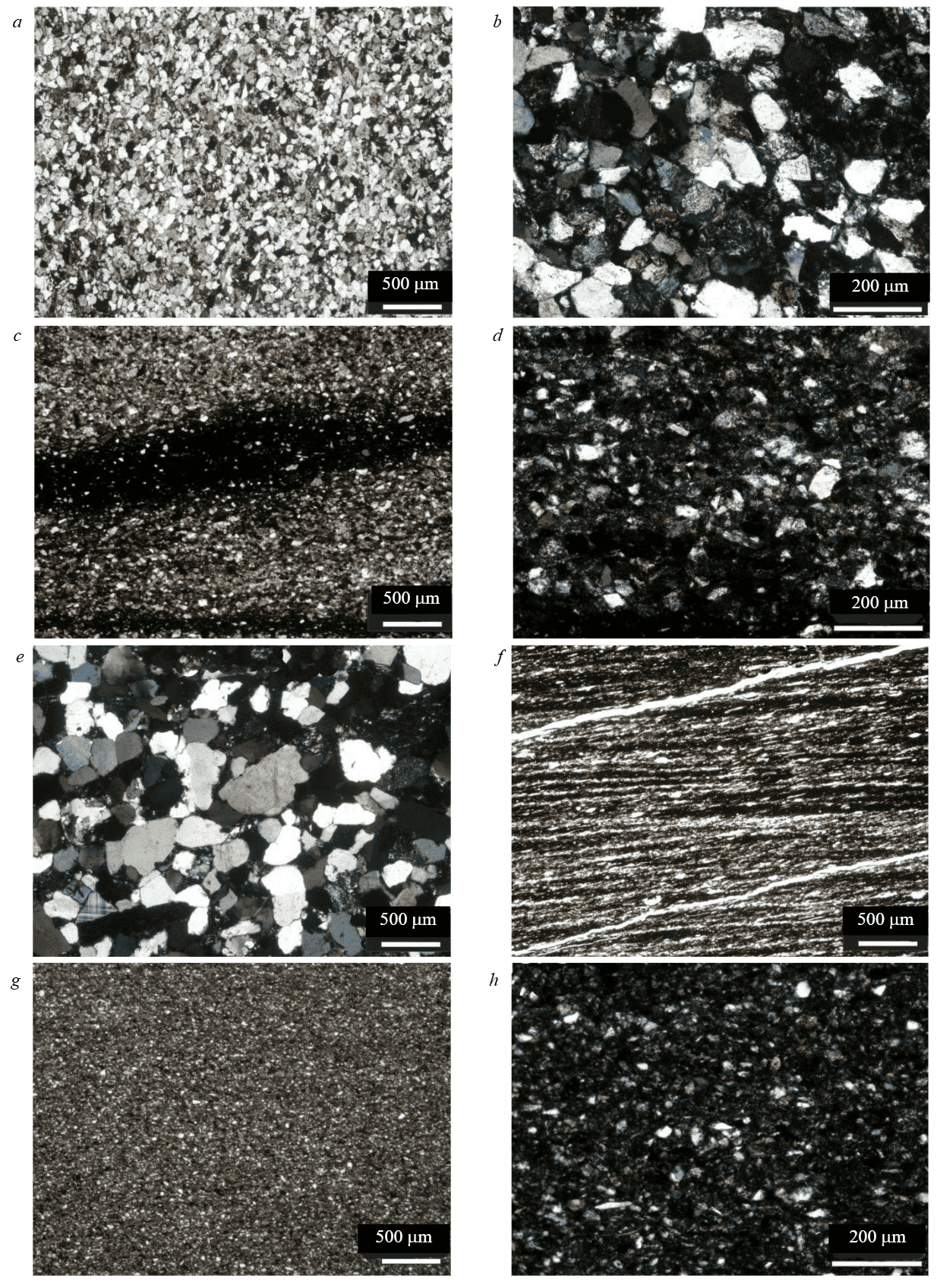

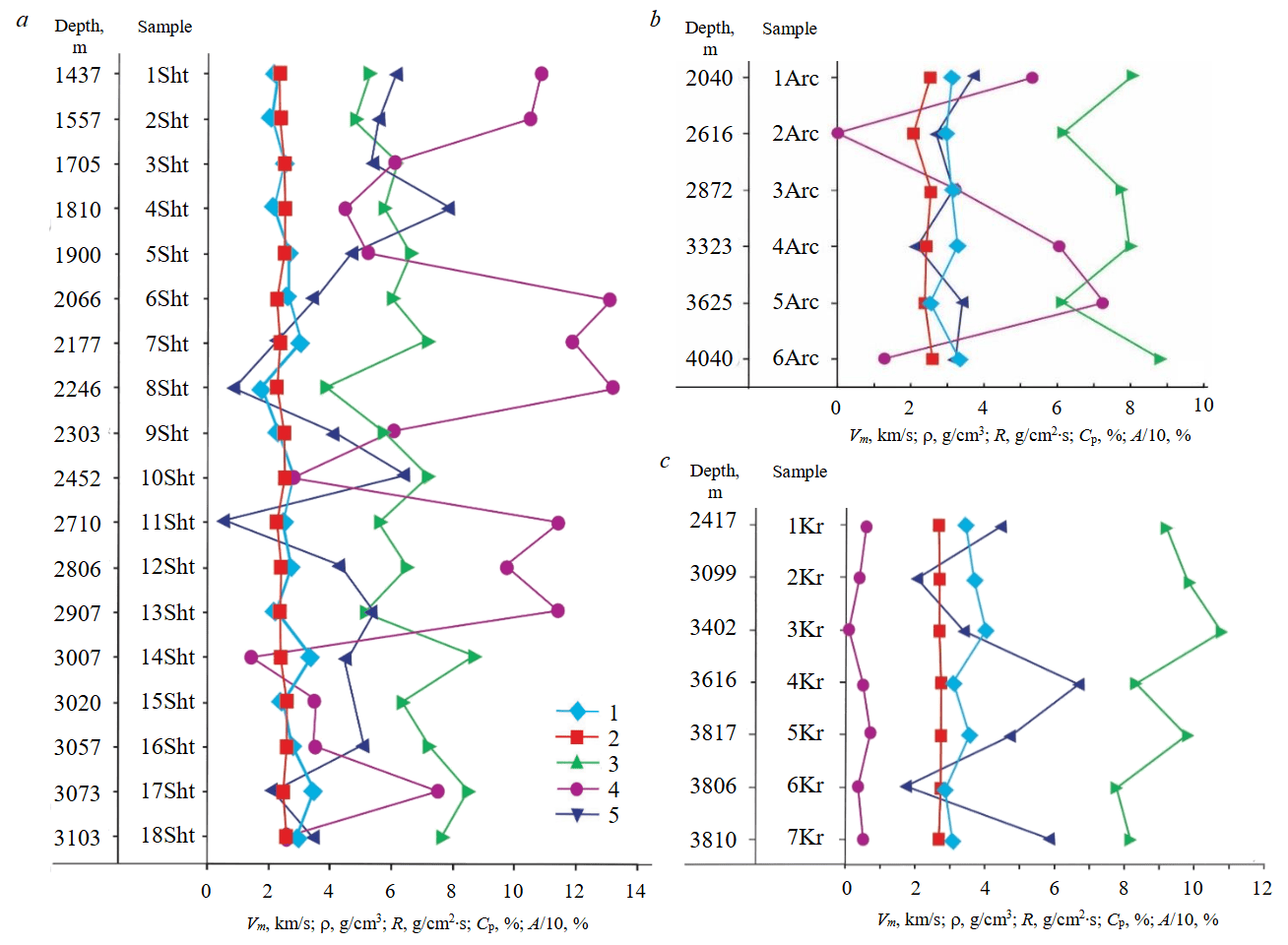

The measurement and calculation results are presented in Table. All samples were described macroscopically and in thin sections (Fig.2). Figure 3 shows the core measurement results for the most representative wells in terms of the number of samples: Shtokmanskaya-1, Arkticheskaya-1, and Krestovaya-1.

Core description in thin sections

The studied core collection is represented by sedimentary rocks: sandstones, siltstones, and limestones, often with interlayers of carbonaceous material. Quartz grains are ubiquitous in the rocks – colorless, with low relief, gray interference colors, and typical undulatory extinction. Microcline fragments, identified by their gridiron twinning, and acidic plagioclases – colorless, with low relief, gray interference colors, and polysynthetic twins with thin twin lamellae – are widely distributed. Mica is present everywhere, typically as separate colorless flakes, with characteristic low relief, bright interference colors, and sparkling extinction. Individual zircon grains are common, characterized by high relief and bright interference colors with zoning. Sericite, which forms small yellowish flakes, and rarely chlorite with typical dirty-gray interference colors, typically develops on individual feldspar grains.

Many samples (sandstones, siltstones, etc.) are very similar to each other in thin sections, minor differences in the percentage content and size of fragments of individual minerals. A brief description of sample compositions is given in Table. Mineral alterations in thin sections show that most of the studied sediments exhibit features typical of late catagenesis (mesocatagenesis) or early metagenesis (apocatagenesis) phases.

Physical properties of well core

Shtokmanskaya-1 well. Rock density ρ varies slightly through the section from 2.26 to 2.6 g/cm3 and tends to gradually increase with depth (Table, Fig.3, а). The average longitudinal wave velocity Vm does not depend on density but also varies slightly and gradually increases with depth. Density directly influences specific acoustic impedance, which changes significantly through the section and mirrors the variations in Vm.

Physical properties of the core samples

|

Sample |

Depth, m;age |

Rock, composition |

Longitudinal waves velocity Vx; Vy; Vz, km/s |

Average velocityVm, km/s |

Densityρ, g/сm3 |

Specific acoustic impedanceR, g/сm2∙s |

Elastic anisotropy indexА, % |

Open porosity, Cp, % |

|

Shtokmanskaya-1 well |

||||||||

|

1Sht |

1437;K1 |

Fine-grained arkose sandstone (0.1-0.5 mm, predominantly 0.15 mm) thin-layered; pore-filling cement of chlorite-sericite composition, locally ferruginous |

2.92; 2.80; 1.14 |

2.29 |

2.31 |

5.29 |

61.44 |

10.8 |

|

2Sht |

1557;K1 |

Fine-grained arkose sandstone (0.1-0.5 mm, predominantly 0.15 mm); pore-filling cement of chlorite-sericite composition, locally ferruginous |

2.25; 2.78; 1.17 |

2.07 |

2.31 |

4.78 |

56.06 |

10.5 |

|

3Sht |

1705;K1 |

Fine-grained arkose sandstone (0.1-0.5 mm, predominantly 0.15 mm) thinly horizontally layered; pore-filling cement of chlorite-sericite composition, locally ferruginous |

3.12; 2.92; 1.40 |

2.48 |

2.50 |

6.20 |

53.64 |

6.1 |

|

4Sht |

1810;K1 |

Massive limestone |

2.20; 3.30; 0.93 |

2.14 |

2.51 |

5.37 |

78.38 |

4.4 |

|

5Sht |

1900;J3 |

Fine-grained arkose sandstone (0.1-0.5 mm, predominantly 0.15 mm) thin-layered with open fractures; pore-filling cement of chlorite-sericite composition, locally ferruginous |

2.64; 3.52; 1.77 |

2.64 |

2.51 |

6.63 |

46.87 |

5.2 |

|

6Sht |

2066;J2 |

Fine-grained arkose sandstone (0.1-0.5 mm, predominantly 0.15 mm) thin-layered, bioturbite structure; pore-filling cement of chlorite-sericite composition, locally ferruginous |

2.98; 3.01; 1.88 |

2.62 |

2.29 |

6.00 |

34.76 |

13.1 |

|

7Sht

|

2177;J2 |

Fine-grained arkose sandstone (0.1-0.5 mm, predominantly 0.15 mm) thin-layered, bioturbite structure; pore-filling cement of chlorite-sericite composition, locally ferruginous |

3.03; 3.07; 2.33 |

3.02 |

2.36 |

7.13 |

22.91 |

11.8 |

|

8Sht |

2246;J2 |

Medium-grained quartz sandstone (0.1-1.2 mm, predominantly 0.4-0.5 mm); film cement of chlorite-sericite composition, locally quartz regenerative |

1.79; 1.95; 1.73 |

1.72 |

2.26 |

3.89 |

8.84 |

13.2 |

|

9Sht |

2303;J2 |

Fine-grained arkose sandstone (0.1-0.5 mm, predominantly 0.15 mm) cross-bedded, bioturbite structure; pore-filling cement of chlorite-sericite composition, locally ferruginous |

3.01; 2.18; 1.72 |

2.30 |

2.50 |

5.75 |

40.20 |

6.1 |

|

10Sht |

2452;J1 |

Limestone thin-layered |

3.56; 3.50; 1.33 |

2.80 |

2.57 |

7.19 |

64.17 |

2.8 |

|

11Sht |

2710;J1 |

Medium-grained quartz sandstone (0.1-1.2 mm, predominantly 0.4-0.5 mm) massive; film cement of chlorite-sericite composition, locally quartz regeneration cement |

2.55; 2.46; 2.38 |

2.46 |

2.28 |

5.61 |

4.89 |

11.4 |

|

12Sht |

2806;T3 |

Fine-grained arkose sandstone (0.1-0.5 mm, predominantly 0.15 mm); pore-filling cement of chlorite-sericite composition, locally ferruginous |

3.05; 3.32; 1.79 |

2.72 |

2.39 |

6.50 |

42.93 |

9.7 |

|

13Sht |

2907;T3 |

Fine-grained arkose sandstone (0.1-0.5 mm, predominantly 0.15 mm); pore-filling cement of chlorite-sericite composition, locally ferruginous |

2.94; 2.22; 1.53 |

2.23 |

2.33 |

5.20 |

53.82 |

11.5 |

|

14Sht |

3007;T3 |

Fine-grained arkose sandstone (0.1-0.5 mm, predominantly 0.15 mm) horizontally layered; pore-filling cement of chlorite-sericite composition, locally ferruginous |

3.89; 4.06; 2.14 |

3.36 |

2.59 |

8.70 |

44.73 |

1.4 |

|

15Sht |

3020;T3 |

Fine-grained arkose sandstone (0.1-0.5 mm, predominantly 0.15 mm) cross-bedded; pore-filling cement of chlorite-sericite composition, locally ferruginous |

2.53; 3.28; 1.61 |

2.47 |

2.57 |

6.35 |

47.89 |

3.5 |

|

16Sht |

3057;T3 |

Fine-grained arkose sandstone (0.1-0.5 mm, predominantly 0.15 mm) thin-layered, bioturbite; pore-filling cement of chlorite-sericite composition, locally ferruginous |

2.61; 3.79; 1.83 |

2.74 |

2.64 |

7.23 |

50.93 |

3.5 |

|

17Sht |

3073;T3 |

Fine-grained arkose sandstone (0.1-0.5 mm, predominantly 0.15 mm) thin-layered; pore-filling cement of chlorite-sericite composition, locally ferruginous |

3.72; 3.82; 2.86 |

3.47 |

2.49 |

8.64 |

21.51 |

7.5 |

|

18Sht

|

3103;T3 |

Fine-grained arkose sandstone (0.1-0.5 mm, predominantly 0.15 mm) micaceous, cross-bedded; pore-filling cement of chlorite-sericite composition, locally ferruginous |

2.79; 3.66; 2.26 |

2.90 |

2.60 |

7.54 |

34.48 |

2.6 |

|

Average values |

2.43 |

2.43 |

5.9 |

42.69 |

7.5 |

|||

|

Arkticheskaya-1 well |

||||||||

|

1Arc |

2040;K1 |

Fine-grained arkose sandstone (0.1-0.5 mm, predominantly 0.15 mm); pore-filling cement of chlorite-sericite composition, locally ferruginous |

3.73; 3.52; 2.20 |

3.15 |

2.56 |

8.06 |

37.24 |

5.4 |

|

2Arc |

2616;J2 |

Silt-clay rock, thin-layered with shell fragments |

3.32; 3.26; 2.30 |

2.96 |

2.09 |

6.19 |

27.34 |

0.0 |

|

3Arc |

2872;J2 |

Fine-grained arkose sandstone (0.1-0.5 mm, predominantly 0.15 mm) cross-bedded; pore-filling cement of chlorite-sericite composition, locally ferruginous |

3.45; 3.48; 2.28 |

3.07 |

2.53 |

7.77 |

31.52 |

3.3 |

|

4Arc |

3323;J1 |

Fine-medium-grained arkose sandstone (0.1-0.5 mm, predominantly 0.2-0.3 mm) massive; film chlorite-sericite cement, locally regenerated quartz |

3.51; 3.61; 2.69 |

3.27 |

2.45 |

8.01 |

21.83 |

6.1 |

|

5Arc |

3625;T3 |

Medium-grained arkose sandstone (0.1-0.8 mm, predominantly 0.4-0.5 mm) massive; film chlorite-sericite cement, locally regenerated quartz |

2.87; 2.93; 1.83 |

2.54 |

2.41 |

6.12 |

34.44 |

7.3 |

|

6Arc |

4040;T3 |

Limestone, grain size ≤ 0.1-0.15 mm, thin-layered |

3.80; 3.87; 2.49 |

3.39 |

2.60 |

8.81 |

32.43 |

1.3 |

|

Average values |

3.06 |

2.44 |

7.47 |

30.75 |

3.9 |

|||

|

Krestovaya-1 well |

||||||||

|

1Kr |

2417;T1 |

Fine-grained arkose sandstone (0.1-0.2 mm) thinly horizontally layered; carbonate cement of basal type |

3.93; 4.18; 2.22 |

3.4 |

2.68 |

9.22 |

43.86 |

0.6 |

|

2Kr |

3099;T1 |

Fine-grained arkose sandstone (0.1-0.2 mm); carbonate cement of basal type |

4.25; 3.24; 3.47 |

3.65 |

2.70 |

9.85 |

20.40 |

0.4 |

|

3Kr |

3402;T1 |

Fine-grained arkose sandstone (0.1-0.5 mm, predominantly 0.15 mm); pore-filling cement of chlorite-sericite composition, locally ferruginous |

4.48; 4.64; 2.91 |

4.01 |

2.69 |

10.79 |

33.71 |

0.1 |

|

4Kr |

3616;T1 |

Fine-grained arkose sandstone (0.1-0.2 mm) thin-layered; carbonate cement of basal type |

2.98; 4.51; 1.67 |

3.05 |

2.74 |

8.36 |

65.91 |

0.5 |

|

5Kr |

3817;T1 |

Fine-grained arkose sandstone (0.1-0.2 mm) thin-layered; carbonate cement of basal type |

4.40; 4.10 2.19 |

3.56 |

2.74 |

9.75 |

47.62 |

0.7 |

|

6Kr |

3806;T1 |

Fine-grained arkose sandstone (0.1-0.2 mm) thin-layered; carbonate cement of basal type |

2.94; 3.21; 2.50 |

2.88 |

2.72 |

7.83 |

17.60 |

0.4 |

|

7Kr |

3910;P2 |

Silt-clay rock, thin-layered |

3.07; 4.31; 1.77 |

3.05 |

2.70 |

8.23 |

58.89 |

0.5 |

|

Average values |

3.38 |

2.71 |

9.16 |

41.14 |

0.4 |

|||

|

Admiralteyskaya-1 well |

||||||||

|

1Adm |

1845;P2 |

Massive carbonaceous limestone |

4.16; 3.23; 3.97 |

3.79 |

2.70 |

10.23

|

18.33 |

1.2 |

|

2Adm |

2047;P2 |

Thin-layered limestone |

3.11; 4.67; 2.34 |

3.37 |

2.65 |

8.93 |

49.82 |

7.0 |

|

3Adm |

2330;P1-2 |

Massive limestone |

4.60; 4.40; 3.49 |

4.16 |

2.73 |

11.36 |

20.11 |

0.7 |

|

4Adm |

2640;P1 |

Massive limestone |

4.38; 3.92; 1.56 |

3.31 |

2.72 |

9.00 |

65.19 |

1.1 |

|

Average values |

3.66 |

2.7 |

9.88 |

38.36 |

2.5 |

|||

|

Ludlovskaya-1 well |

||||||||

|

1Lu |

1717;J2 |

Fine-grained arkose sandstone (0.1-0.5 mm, predominantly 0.15 mm) thinly cross-bedded; pore-filling cement of chlorite-sericite composition, locally ferruginous |

3.91; 3.31; 2.16 |

3.13 |

2.57 |

8.04 |

40.18 |

4.1 |

|

2Lu |

2218;J1 |

Fine-grained arkose sandstone (0.1-0.5 mm, predominantly 0.15 mm); pore-filling cement of chlorite-sericite composition, locally ferruginous |

3.44; 3.72; 1.36 |

2.84 |

2.56 |

7.27 |

64.20 |

4.2 |

|

3Lu |

2881;T3 |

Fine-grained arkose sandstone (0.1-0.5 mm, predominantly 0.15 mm) cross-bedded; pore-filling cement of chlorite-sericite composition, locally ferruginous |

3.74; 3.52; 2.13 |

3.13 |

2.57 |

8.04 |

39.44 |

1.5 |

|

Average values |

3.03 |

2.57 |

7.79 |

47.94 |

3.3 |

|||

|

Severo-Kildinskaya-82 well |

||||||||

|

1SK |

3413;T1 |

Fine-grained arkose sandstone (0.1-0.5 mm, predominantly 0.15 mm) massive; pore-filling cement of chlorite-sericite composition, locally ferruginous |

3.61; 3.45; 2.01 |

3.02 |

2.67 |

8.04 |

41.27 |

1.6 |

|

2SK

|

3774;T1 |

Fine-grained arkose sandstone (0.1-0.5 mm, predominantly 0.15 mm) massive; pore-filling cement of chlorite-sericite composition, locally ferruginous |

2.74; 2.82; 1.47 |

2.34 |

2.50 |

5.85 |

45.77 |

5.9 |

|

3SK |

3875;T1 |

Fine-grained arkose sandstone (0.1-0.5 mm, predominantly 0.15 mm) massive; pore-filling cement of chlorite-sericite composition, locally ferruginous |

2.87; 2.27; 1.82 |

2.32 |

2.47 |

5.73 |

32.11 |

5.3 |

|

4SK |

4007;T1 |

Arkose sandstone, fine-medium-grained (0.1-0.5 mm, predominantly 0.2-0.3 mm) massive; film cement of chlorite-sericite composition, locally regenerated quartz |

4.19; 4.29; 3.13 |

3.87 |

2.54 |

9.83 |

23.49 |

5.8 |

|

Average values |

2.89 |

2.54 |

7.34 |

35.66 |

4.6 |

|||

The elastic anisotropy index A decreases down the section, varies substantially, and does not always align in the direction of change with the previous parameters. Porosity Cp exhibits the strongest variation, from 1.4 to 13.2 %, and in most cases is inversely proportional to the elastic parameters (Vm, R, A). The productive interval of this field with unique gas-condensate reserves is located within the depth range of 1813-2479 m [28]. According to [12], the Shtokmanskaya-1 well penetrated two gas-condensate intervals, at depths of ~1850-1900 m and ~2100-2200 m. Apparently, the samples 6Sht-8Sht with the highest porosity values Cp = 11.5-13.2 % belong to the second interval (2100-2200 m), although high porosity is also noted for samples 1Sht, 2Sht and 11Sht-13Sht (see Table, Fig.3).

Arkticheskaya-1 well. Rock density, as in the Shtokmanskaya well, changes weakly with depth from 2.4 to 2.6 g/cm3, decreasing to 2.09 g/cm3 at a depth of 2616 m (sample 2Arc, see Table, Fig.3, b). The average longitudinal wave velocity Vm and specific acoustic impedance R change synchronously through the section, not increasing with depth. The elastic anisotropy index A changes synchronously with R for the upper samples (1Arc-3Arc) and is in antiphase with R for the lower ones (4Arc-6Arc). The porosity coefficient Ср varies significantly from 0 to 7.1 %, increasing in the three lower samples. Data on the productivity of this well and the Arkticheskaya area in general are not available in open publications.

Fig.2. Photographs of thin sections of some rock samples: а, b – 4SK (fine-medium-grained arkose sandstone); c, d – 3Kr (fine-grained poorly sorted arkose sandstone); e – 8Sht (medium-grained quartz sandstone); f – 2Arc (silt-clay rock with distinct layering); g, h – 7Kr (silt-clay rock)

Fig.3. Variations in the physical properties of core along the section: a ‒ Shtokmanskaya-1 well; b ‒ Arkticheskaya-1 well; c ‒ Krestovaya-1 well

1 – average velocity Vm, km/s; 2 – density r, g/cm3; 3 – specific acoustic impedance R, g/сm2∙s; 4 – porosity coefficient Ср, %; 5 – elastic anisotropy indexА/10, %

Krestovaya-1 well. Sample density falls within a narrow range (2.68-2.74 g/cm3) due to rock homogeneity (see Table). The average velocity of longitudinal waves Vm and specific acoustic impedance R gradually decrease with depth. The elastic anisotropy index A varies significantly, being in antiphase with R for the upper samples (1Kr-5Kr), and changing synchronously with R for the lower samples (6Kr and 7Kr). The porosity coefficient Cp is low (0.1-0.7 %) in all samples, raising doubts about the possible presence of hydrocarbon accumulations here.

Discussion

Physical properties of core from the Kola Superdeep Borehole (SD-3) and a number of other wells drilled in ancient metamorphic rocks, as well as measurements of core from Cretaceous deposits of the Leningradskaya area (the Kara Sea shelf) [15], have shown that the elastic anisotropy of rocks, as a physical property related to the composition, structure, and fracture-pore system of the rock, reflects the tectonics of the object (rock massif) and is primarily caused by geodynamic processes [15, 29]. Recent studies [30] have obtained new information on the geological structure of the northern part of the Kara Sea shelf near the Severnaya Zemlya Archipelago. In general, the physical properties of rocks not only provide necessary information about their reservoir properties but also indicate the hydrocarbon potential of shelf deposits. Moreover, the formation of such a property of a sedimentary basin as hydrocarbon potential is ultimately determined by the evolution of the dynamic system of the basin itself [12, 31].

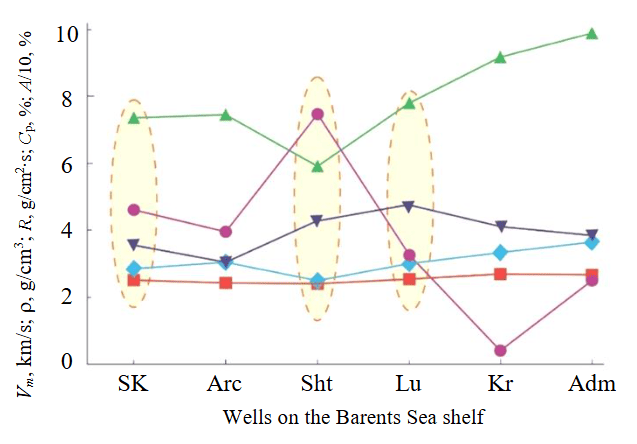

Figure 4 shows the average values of physical properties for each studied well (see Table), which represent characteristic points along a conditional profile oriented from southwest to northeast.

Despite the small number of studied samples, based on the average values of physical properties calculated for all wells (see Table, Fig.3), and using additional information, some conclusions can be drawn. According to [8, 28], three areas are productive: Severo-Kildinskaya-1 – gas, Shtokmanskaya-1 – gas-condensate, and Ludlovskaya-1 – gas. In terms of their geological position, productive wells are located at the boundaries of the basins, while non-productive ones are in the center of the South Barents Basin (Arkticheskaya-1) and within the Admiralty High (Krestovaya-1 and Admiralteyskaya-1, see Fig.1).

Fig.4. Average values of physical properties of wells core (from southwest to northeast).

Productive wells are highlighted by ellipses

For legend, see Fig.3

The physical properties of core samples from Severo-Kildinskaya, Shtokmanskaya, and Ludlovskaya gas wells (Fig.4) are similar in their relatively low Vm and R values and higher Cp and A values. All these parameters depend on the presence of pores and fractures. The development of a fracture-pore system leads to an increase in open porosity coefficients and (or) elastic anisotropy, while simultaneously reducing the average velocity of longitudinal waves and decreasing specific acoustic impedance. The highest open porosity values are noted in the Shtokmanskaya-1 well, which has unrivalled reservoir properties. In the Ludlovskaya-1 well, with low open porosity, the value of the elastic anisotropy index increases, which may be associated with the presence of fracture systems. It is known that the role of fracturing in fluid filtration increases especially in dense, low-porosity rock varieties with low intergranular permeability [32]. Such rocks can form fracture-pore, pore-fracture, and in some cases, purely fracture reservoirs, where fluid filtration occurs primarily through fractures. The reservoir properties of low-productivity wells (Arkticheskaya-1, Krestovaya-1, Admiralteyskaya-1) are inferior in this respect to gas wells (Ludlovskaya, Severo-Kildinskaya-82, Fig.4), expressed in low values of open porosity and elastic anisotropy index, but elevated R and Vm parameters.

Thus, the physical properties of the studied core samples differ noticeably between productive and non-productive wells.

If we consider the petrographic properties of rocks using the example of the Shtokmanskaya-1 well (productive) and Arkticheskaya-1 and Krestovaya-1 wells (non-productive), then with the same rock type (arkose sandstones), a difference is observed both in the granulometric composition of the rocks and in the cementation type. The sandstones of the Shtokmanskaya well are characterized by a larger grain size (0.1-0.5 mm), while the sandstones from the Arkticheskaya-1 and Krestovaya-1 wells are fine-grained (0.1-0.2 mm). The Shtokmanskaya-1 well features pore-filling cement, the Arkticheskaya-1 well has thin-film cement, and the Krestovaya-1 well has cement of the basal type. The reservoir properties of sandstones decrease during the transition from pore-filling to thin-film and basal cement [33]. In the Shtokmanskaya well, against the background of sandstones, two limestone samples (4Sht and 10Sht) stand out in the section, which are characterized by the lowest porosity but high anisotropy, which may indicate the presence of internal fractures. Similar thinly laminated or massive limestones with very low porosity and low anisotropy are also noted in the Arkticheskaya-1 well (2Arc and 6Arc, see Table, Fig.3). Possibly, the absence of pores in the limestones is related to the small grain size ≤ 0.1-0.15 mm, since the decrease in reservoir properties of terrigenous (clastic) rocks can be directly related to the reduction in the size of their granulometric composition.

Based on the data presented in the article, it can be argued that hydrocarbon fields in the subsurface of the South Barents Basin should be sought at a relatively short distance from its tectonic boundaries. It is believed that during gas generation in the South Barents thermal chamber, these vast volumes of gas migrated to relatively elevated areas, such as the Shtokman-Ludlovskaya area [11]. From another point of view, fluids were squeezed towards the edges of the basin due to powerful lithostatic pressure; fluids migrated from areas of overpressure to peripheral zones of decompaction [12]. In any case, the gas-condensate and gas fields discovered in the South Barents Basin ‒ Murmanskoye, Severo-Kildinskoye, Shtokmanskoye, Ledovoye, Ludlovskoye are confined to peripheral zones [8].

The obtained results can be useful in studying geotectonic structures prospective for hydrocarbons. Petrophysical methods can be applied to promptly screen out potentially empty areas at the preliminary stage of analyzing geophysical (seismological) materials. Lithological and petrophysical data from core samples of deep wells in oil and gas fields can also be used in mathematical modeling methods for constructing digital core models [34, 35], which are applied in studies of complex reservoir rocks that are difficult to experiment on or in assessing oil and gas reserves [20].

Conclusion

Based on the analysis of core from six wells in the South Barents Basin according to five different physical properties (density, elasticity, elastic anisotropy index, specific acoustic impedance, and porosity) and petrographic features, the following conclusions can be drawn.

Rocks from non-productive wells Arkticheskaya-1, Admiralteyskaya-1, and Krestovaya-1, located in the central part of the South Barents Basin and within the Admiralty High, differ in their physical properties from rocks of gas and gas-condensate wells Shtokmanskaya-1, Severo-Kildinskaya-82, and Ludlovskaya-1, located near the boundaries of the South Barents Basin. Core samples from productive wells have lower values of Vm and R and higher values of Cp and/or A than non-productive wells. It is this combination of petrophysical parameters that provides the reservoir properties of rocks prospective for hydrocarbons. The petrographic variation of the reservoir properties of the studied rocks in productive and non-productive wells is reflected in the decrease in the granulometric composition of the rocks and in the transition from pore-filling to thin-film and basal cement.

When searching for geotectonic structures prospective for hydrocarbons, petrophysical methods can be used to promptly screen out potentially empty areas at the preliminary stage of analyzing geophysical (seismological) materials.

References

- Tectostratigraphic Atlas of the Eastern Arctic. Ed. by O.V.Petrov, M.Smelror. St. Petersburg: VSEGEI, 2020, p. 152 (in Russian).

- Gusev E.A. Results and prospects of geological mapping of the Arctic shelf of Russia. Journal of Mining Institute. 2022. Vol. 255, p. 290-298. DOI: 10.31897/PMI.2022.50

- Karev V., Kovalenko Y., Ustinov K. Directional Unloading Method is a New Approach to Enhancing Oil and Gas Well Productivity. Geomechanics of Oil and Gas Wells. Springer, 2020, p. 155-166. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-030-26608-0_10

- Dvoinikov M.V., Leusheva E.L. Modern trends in the development of hydrocarbon resources. Journal of Mining Institute. 2022. Vol. 258, p. 879-880 (in Russian).

- Dmitrieva D., Romasheva N. Sustainable Development of Oil and Gas Potential of the Arctic and Its Shelf Zone: The Role of Innovations. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2020. Vol. 8. Iss. 12. N 1003. DOI: 10.3390/jmse8121003

- Archegov V.B., Nefedov Y.V. Oil and gas exploration strategy in evaluation of fuel and energy potential of Russian Arctic shelf. Journal of Mining Institute. 2015. Vol. 212, p. 5-13 (in Russian).

- Innovative development vector of JSC MAGE. Ed. by G.S. Kazanin, G.I. Ivanov. St. Petersburg, 2017, p. 263 (in Russian).

- Shipilov E.V., Murzin R.R. Hydrocarbon fields of Russia’s West Arctic shelf: geology and distribution regularities. Geologiya nefti i gaza. 2001. N 4, p. 6-19 (in Russian).

- Evdokimov A.N., Smirnov A.N., Fokin V.I. Mineral resources in Arctic islands of Russia. Journal of Mining Institute. 2015. Vol. 216, p. 5-12 (in Russian).

- Prischepa O., Nefedov Y., Nikiforova V. Arctic Shelf Oil and Gas Prospects from Lower-Middle Paleozoic Sediments of the Timan-Pechora Oil and Gas Province Based on the Results of a Regional Study. Resources. 2022. Vol. 11. Iss. 1. N 3. DOI: 10.3390/resources11010003

- Margulis E.A. Factors of forming the unique Shtokman-Ludlov knot of gas accumulation in the Barents Sea. Neftegazovaya Geologiya. Teoriya i praktika. 2008. Vol. 3. N 2, p. 9 (in Russian).

- Shipilov E.V. Hydrocarbons fields of the Russian Arctic shelf: Geology and regularities of the disposal. Vestnik of MSTU. 2000. Vol. 3. N 2, p. 339-351 (in Russian).

- Tsybulya L.A., Levashkevich V.G. Thermal field of the Barents Sea region. Apatity: Kolskii nauchnyi tsentr RAN, 1992, p. 112 (in Russian).

- Ilchenko V.L. Fission tracks analysis to determine the paleotemperature regime of the Barents Sea sediments. Litologiya i poleznye iskopaemye. 1995. N 5, p. 552-557 (in Russian).

- Ilchenko V.L., Chikirev I.V. Some Physical Properties of Cretaceous Rocks in the Southwestern Part of the Kara Sea Shelf. Lithology and Mineral Resources. 2009. Vol. 44. N 4, p. 328-338. DOI: 10.1134/S0024490209040026

- Drozdov A., Gorbyleva Y., Drozdov N., Gorelkina E. Perspectives of application of simultaneous water and gas injection for utilizing associated petroleum gas and enhancing oil recovery in the Arctic fields. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 2021. Vol. 678. N 012039. DOI: 10.1088/1755-1315/678/1/012039

- Kozhevnikov E.V., Turbakov M.S., Riabokon E.P., Poplygin V.V. Effect of Effective Pressure on the Permeability of Rocks Based on Well Testing Results. Energies. 2021. Vol. 14. Iss. 8. N 2306. DOI: 10.3390/en14082306

- Dasgupta T., Mukherjee S. Sediment Compaction and Applications in Petroleum Geoscience. Springer, 2020, p. 122. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-030-13442-6

- Zhukov V.S., Kuzmin Yu.O. Experimental evaluation of compressibility coefficients for fractures and intergranular pores of an oil and gas reservoir. Journal of Mining Institute. 2021. Vol. 251, p. 658-666. DOI: 10.31897/PMI.2021.5.5

- Belozerov I.P., Gubaidullin M.G. Concept of technology for determining the permeability and porosity properties of terrigenous reservoirs on a digital rock sample model. Journal of Mining Institute. 2020. Vol. 244, p. 402-407. DOI: 10.31897/PMI.2020.4.2

- Kozlovsky Y.A. The Superdeep Well of the Kola Peninsula. Springer-Verlag, 1987, p. 571. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-642-71137-4

- Baker R.O., Yarranton H.W., Jensen J.L. Practical Reservoir Engineering and Characterization. Elsevier, 2015, p. 534. DOI: 10.1016/C2011-0-05566-7

- Peng Xiang, Hongguang Ji, Jingming Geng, Yiwei Zhao. Characteristics and Mechanical Mechanism of In Situ Unloading Damage and Core Discing in Deep Rock Mass of Metal Mine. Shock and Vibration. 2022. Vol. 2022. N 5147868. DOI: 10.1155/2022/5147868

- Sakulina T.S., Roslov Yu.V., Ivanova N.M. Deep seismic investigations in the Barents and Kara seas. Izvestiya, Physics of the Solid Earth. 2003. Vol. 39. N 6, p. 438-452.

- Systematics and classification of sedimentary rocks and their analogues. Ed. by V.N.Shvanov. St. Petersburg: Nedra, 1998, p. 352 (in Russian).

- Yang Gao, Zhizhang Wang, Yuanqi She et al. Mineral characteristic of rocks and its impact on the reservoir quality of He 8 tight sandstone of Tianhuan area, Ordos Basin, China. Journal of Natural Gas Geoscience. 2019. Vol. 4. Iss. 4, p. 205-214. DOI: 10.1016/j.jnggs.2019.07.001

- Barletta A. Fluid Flow in Porous Media. Routes to Absolute Instability in Porous Media. Springer, 2019, p. 121-133. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-030-06194-4_6

- Kozlov S.A. Engineering geology of the Western Arctic shelf of Russia. St. Petersburg: VNIIOkeangeologiya, 2004, p. 147 (in Russian).

- Artyushkov E.V. On the origin of the seismic anisotropy of the lithosphere. Geophysical Journal International. 1984. Vol. 76. Iss. 1, p. 173-178. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-246X.1984.tb05033.x

- Gusev E.A., Krylov A.A., Urvantsev D.M. et al. Geological structure of the northern part of the Kara Shelf near the Severnaya Zemlya archipelago according to recent studies. Journal of Mining Institute. 2020. Vol. 245, p. 505-512. DOI: 10.31897/PMI.2020.5.1

- Lavrenova E.A., Shcherbina Yu.V., Mamedov R.A. Modeling of hydrocarbon systems and quantitative assessment of the hydrocarbon potential of Eastern Arctic seas. Proceedings of higher educational establishments. Geology and Exploration. 2020. Vol. 63. N 4, p. 23-38 (in Russian). DOI: 10.32454/0016-7762-2020-63-4-23-38

- Belonovskaya L.G., Bulach M.H., Gmid L.P. The role of fracture in the formation of capacitive-filtration space of complex reservoirs. Neftegazovaya Geologiya. Teoriya i praktika. 2007. Vol. 2, p. 18 (in Russian).

- Smirnova N.V. Types of cement and their effect on the permeability of sandy rocks. Geologiya nefti i gaza. 1959. N 7, p. 33-38 (in Russian).

- Samylovskaya E., Makhovikov A., Lutonin A. et al. Digital Technologies in Arctic Oil and Gas Resources Extraction: Global Trends and Russian Experience. Resources. 2022. Vol. 11. Iss. 3. N 29. DOI: 10.3390/resources11030029

- Esiri A.E., Jambol D.D., Ozowe C. Enhancing reservoir characterization with integrated petrophysical analysis and geostatistical methods. Open Access Research Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies. 2024. Vol. 7. Iss. 2, p. 168-179. DOI: 10.53022/oarjms.2024.7.2.0038