High-alumina gneisses of the Chupa Formation in the Belomorian Mobile Belt: metamorphic conditions, partial melting, and the age of migmatites

- 1 — Ph.D. Researcher Institute of Precambrian Geology and Geochronology RAS ▪ Orcid

- 2 — Ph.D., Dr.Sci. Chief Researcher Institute of Precambrian Geology and Geochronology RAS ▪ Orcid

- 3 — Ph.D. Senior Researcher Institute of Precambrian Geology and Geochronology RAS ▪ Orcid

Abstract

Migmatized gneisses of the Chupa paragneiss Formation in the Belomorian Mobile Belt (BMB) of the Fennoscandian Shield have been studied, and the conditions of partial melting during high-grade metamorphism of the rocks were determined. The melting temperatures and pressures, the amount and composition of the melt formed during the anatexis of gneisses in a closed system, were assessed through direct thermodynamic computer modeling of mineral formation and the construction of pseudosections in pressure-temperature coordinates. The mineral formation calculations are based on the principle of Gibbs energy minimization and were performed using the PERPLE_X software package. The bulk compositions of the migmatized rocks from the Chupa Formation, previously classified and grouped based on their major components, were used for the calculations. It is shown that water-saturated partial melting of compositionally diverse gneisses produces granitic or granodiorite-tonalitic melts within a temperature range of 680-730 °C at moderate to moderately high pressures. The study reveals that the key factor controlling the appearance of kyanite in the investigated rocks is a high Al2O3/CaO ratio (at least 5:1) in the protolith, combined with a total alkali content (Na2O + K2O) exceeding CaO. According the Chemical Index of Alteration (CIA), the protoliths of the gneisses contained detrital material of varying sedimentary maturity. The source rocks were likely weakly to moderately weathered. U-Pb ID-TIMS dating of monazite from two samples of garnet-kyanite-biotite migmatite (whole-rock analysis) indicates Paleoproterozoic migmatization of the Chupa gneisses at 1854 ± 5 Ma. This phase of Paleoproterozoic endogenic activity is widely recorded in the BMB and may be associated with the formation of the Lapland-Kola or Svecofennian orogens, located to the northeast and southwest of the belt, respectively.

Funding

The research was carried out at the expense of a grant from the Russian Science Foundation N 25-27-00117.

Introduction

The reconstruction of the formation and evolution mechanisms of continental crust remains one of the most pressing challenges in modern geology [1-3]. Granitoids play a key role in crustal formation processes [4-6], which cover significant areas and contain strategically important gold, iron, copper, rare metals, and rare earth elements, as well as other minerals [7-9]. Therefore, studying of granitoids, the mechanisms of their formation, and their role in crust formation is essential for expanding the country's strategic mineral resource base.

The formation of granitic material through the partial melting of metamorphic rocks plays an important role in tectonics [10-12], as the emergence and subsequent migration of anatectic melt significantly affects the rheology of the migmatized sequences by reducing their mechanical strength and increasing the volume of the metamorphic rocks. The volume, composition, and PT conditions of the granitic melt formation directly depend on the composition of the source rocks, the fluid regime of metamorphism, the closed or open nature of the system with respect to major components and liquid phases, including the mobility of the newly formed melt itself.

The PT melting conditions, quantity, and composition of the melt formed by melting metasedimentary rocks in closed or open systems can be determined through direct thermodynamic modeling by constructing pseudosections in “pressure – temperature” coordinates. For such calculations, the bulk compositions of the migmatized rocks are used. The success of this approach has been demonstrated in recent years in a number of scientific studies [13-15].

In this study, we turned to the analysis of the conditions for the manifestation of partial melting (anatexis) of rocks in the Chupa paragneiss Formation within the Belomorian Mobile Belt (BMB). For this analysis, we used the most diverse possible compositions of the protoliths of the Chupa Formation, allowing us to reveal the specifics of their melting. In addition to the protolith composition, we examined in detail the PTX regime at the onset of the melting process, the fluid regime, and the dependence of anatectic melt compositions on external parameters. Furthermore, to determine the timing of anatexis, U-Pb isotopic dating of monazite extracted from migmatized garnet-kyanite-biotite gneisses of the Chupa Formation was performed. The use of the obtained data makes a significant contribution to understanding the problem of crustal granitoid formation under conditions of elevated lithostatic pressure, which is necessary for reliable tectonic-metamorphic and geodynamic reconstructions.

Brief characteristics of the study area

The BMB is a complex nappe-fold structure, located in the northeastern part of the Fennoscandian Shield. It extends for 700 km along the White Sea as a belt 100-150 km wide, up to the border with Finland, and is bounded to the southwest by the Karelian and to the northeast by the Kola Archean cratons [16]. The BMB consists predominantly of Archean granitoids and migmatized gneisses, with subordinate amounts of Paleoproterozoic meta-intrusive mafic-ultramafic bodies and pegmatites. It represents a system of shallowly northeast-dipping Archean and Proterozoic tectonic nappes [17], complicated by domes. Proterozoic supracrustal formations are absent [16, 18, 19].

In the axial part of the BMB lies the Chupa tectonic nappe (Fig.1), as it is sometimes referred to in the literature, the Suite or Formation. As a Suite within the Belomorian Series, it was delineated during the 1951-1954 geological survey at a scale of 1:50,000 in the territory of the Chupa mica-bearing district. Other researchers, during subsequent geological mapping of the BMB, attributed lithologically similar sequences outside this area to the Chupa Formation. In this work, the neutral term “Formation” is used, as it does not define either the tectonic or stratigraphic nature of the geological unit under consideration, which in this case is not the subject of the study.

The Chupa Formation is considered by researchers as a tectonic nappe of metasedimentary rocks, which overlies the Khetolambina and Keret nappes and, together with them, is underthrust beneath the margin of the Karelian craton as a result of Late Archean subduction [16]. The Chupa tectonic nappe can be traced as a continuous belt or in the form of separate structures across the entire BMB [20]. According to the State Geological Map at a scale of 1:200,000 (Karelian Series, sheet Q-36-XV, XVI) [21], instead of the former Keret, Khetolambina, and Chupa Formations, the Kotozero migmatite-plagiogranite and Khetolambina ortho-amphibolite subcomplexes, as well as the Loukhi Formation, have been delineated. The Chupa Formation is assigned to the Loukhi Formation, the lower boundary of which is established by the abrupt change in rock associations compared to the underlying rocks of the Khetolambina and Kotozero subcomplexes of the Belomorian plutono-metamorphic complex. At the same time, the characteristic rocks of the Loukhi (Chupa) Formation, distinguishing it from others, are kyanite-bearing garnet-biotite, two-mica, and biotite gneisses with subordinate interlayers of amphibole-bearing schists and amphibolite bodies [16].

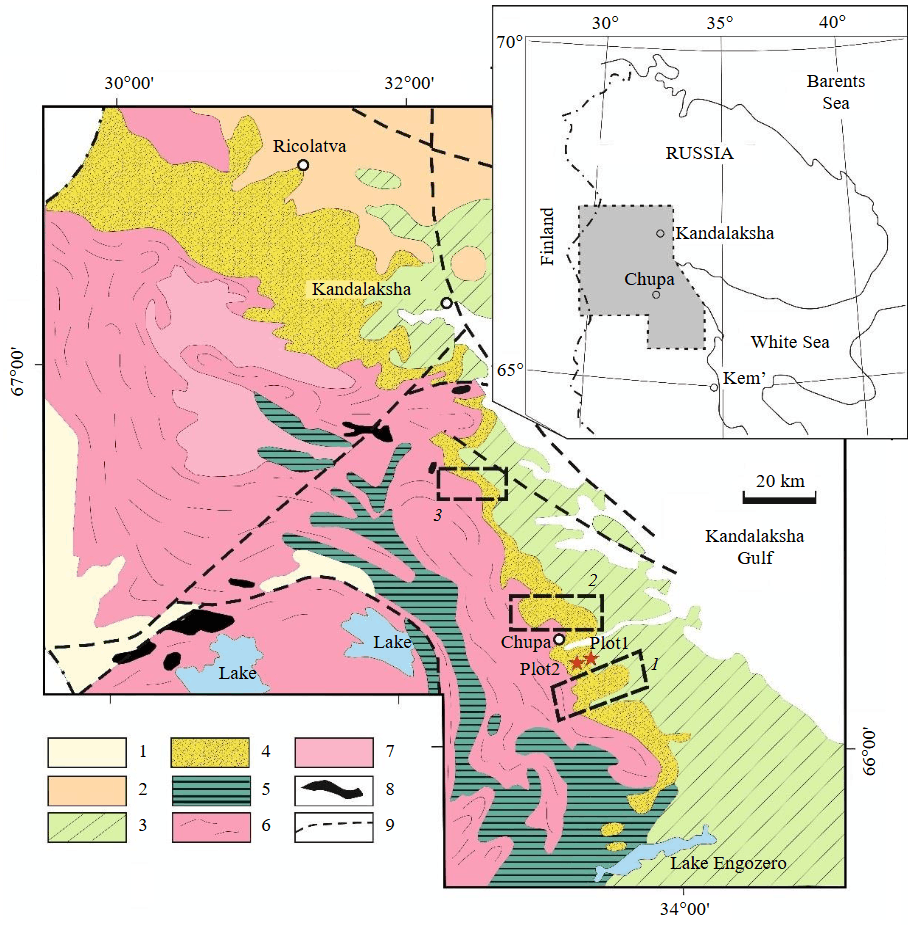

Fig.1. A schematic geological map of the study area indicating the location of the studied sample collection sites (compiled by Yu.V.Miller with modifications by the authors)

1 – Paleoproterozoic troughs; 2 – Svecofennian (Lapland) allochthon, Rikolatva nappe; 3-9 – Late Archean (Belomorian) allochthon: 3 – Khetolambina nappe – tonalites with included bands of mafic and ultramafic rocks, 4 – Chupa nappe – aluminous gneisses, injected by tonalities, 5, 6 – Kovdozero nappe (edge of the Karelian craton in allochthonous position): 5 – North Karelian System of greenstone belts – metabasalts and tuffs of intermediate composition, 6 – predominantly tonalitic infracrustal complex, 7 – Orijärvi nappe – tonalities, 8 – Paleoproterozoic gabbro-norite-lherzolite complex, 9 – faults.

Areas: 1 – Keleynogubsky; 2 – Pulonga-Chupa; 3 – Tupaya Guba – Seryak Asterisks indicate the sample collection points (Plot1, Plot2) for isotopic dating

There are several hypotheses regarding the origin of the Chupa gneisses. Some researchers suggest that they are deeply metamorphosed sediments [22]. Some scientists [18] consider them as products of ultrametamorphic and metasomatic alterations of metavolcanics of intermediate, to a lesser extent felsic and mafic compositions. In a later study [20], it is proposed that the metamorphic rocks of the Chupa Formation formed from poorly differentiated graywackes, whose sources included felsic (predominant), mafic, and apparently, in small amounts, ultramafic components, which most likely were the products of erosion of volcanic complexes, including proto-ophiolites of mafic zones within young ensimatic island arcs 2.8-2.9 Ga, closely associated with graywackes in the sections.

PT regimes and stages of metamorphism of the Belomorian Mobile Belt

The BMB underwent two major stages of metamorphism: Archean (2.9-2.7 Ga) and Paleoproterozoic (2.0-1.7 Ga) [16, 19], under elevated pressures (8-14 kbar). These metamorphic episodes in the Chupa Formation and adjacent amphibolites of the Central Belomorian greenstone belt are associated with two distinct migmatite and leucogranite formation events. The Neoarchean melting episode (2710±15 and 2706±14 Ma, U-Pb zircon ages) is linked to the formation of the Neoarchean Belomorian collisional orogen, while the Paleoproterozoic episode (1944±12 and 1882±9 Ma, U-Pb zircon ages of leucosomes) corresponds to the development of the Paleoproterozoic Lapland-Kola orogen [19].

There are numerous estimates of the thermodynamic regime of metamorphism of rocks in the Belomorian region. The PT parameters of the earliest moderate-pressure granulite stage of metamorphism are: T = 800 °C, P = 6-8 kbar [18]; T = 700-730 °C, P = 6-7 kbar [23]. The later stage of high-pressure amphibolite-facies metamorphism, locally reaching granulite-facies conditions, has the following parameters: T = 750-850 °C, P = 8-9 kbar [24]; T = 730-750 °C, P = 7-8.5 kbar [23].

The timing of the granulite-facies metamorphism in the Tupaya Guba area is estimated by the U-Pb method on zircon from garnet-biotite gneiss as 2.85 Ga, and on zircon from metagabbro as 2.7 Ga [23]. The high-pressure amphibolite-facies metamorphism, following the granulite one and corresponding to the conditions of the kyanite-sillimanite facies series, occurred in the interval of 2.7-2.67 Ga: T = 660-700 °C, P = 12-14 kbar [18]; T = 600-700 °C, P = 8-9 kbar [24]. A Paleoproterozoic stage of amphibolite-facies metamorphism is also distinguished, locally manifested along shearing zones, having lower PT parameters compared to the previous Late Archean amphibolite stage: T = 630-650 °C, P = 7.5 kbar [18]; T = 550-630 °C, P = 6-7 kbar in the area of the Chupa muscovite deposits [24].

For kyanite-bearing gneisses of the Chupa Formation, PT conditions of formation are given for leucosomes of Archean age (~2.68 Ga): P = 9-11 kbar, T = 700-780 °C. At the same time, it is noted that non-migmatized garnet-biotite gneisses are characterized by higher metamorphic parameters: P = 8.5-12.5 kbar, T = 720-840 °C [19]. For the melanosome around an early Paleoproterozoic leucosome in amphibolites (~1.94 Ga), the following conditions have been calculated: T = 625-700 °C, P = 9-11 kbar, while for the late (also Paleoproterozoic, ~1.88 Ga) leucosome crosscutting the early one, peak values (T = 800-830 °C, P = 14-15 kbar) have been established, decreasing to T = 670-700 °C, P = 10-12 kbar.

Zircon dating of kyanite gneisses and amphibolites [25] revealed that the zircon cores from gneisses correspond to Neoarchean events with ages of 2700-2800 Ma, and from amphibolites – to the time of magmatic crystallization (2775±12 Ma). At the same time, the inner rims of zircon from amphibolites and gneisses are associated with Neoarchean metamorphic events with ages of 2650±8 and 2599±10 Ma, respectively, and the outer rims – with Paleoproterozoic metamorphism around 1890 Ma.

Methods and research data

The content of chemical elements in the rocks was analyzed by X-ray fluorescence spectrometry (XRF, Central Laboratory of the Karpinsky Institute). The analyzed sample was mixed with a flux (50 % lithium metaborate and 50 % lithium tetraborate) in a 1:9 ratio and then fused in gold-platinum crucibles. The analysis was performed on pressed fused pellets weighing 4 g. The quantitative content of each element is automatically calculated by comparing the element signals (mass spectra) of the working sample and the calibration mixture. The lower detection limit for oxides was 0.01-0.03 wt.%.

U-Pb isotopic dating. Monazite from the crushed samples of migmatized garnet-kyanite-biotite gneiss was extracted using heavy liquids. Then, the monazite grains were grouped under a binocular microscope taking into account their morphology and size. Each analyzed batch contained from 8 to 12 monazite grains. Chemical decomposition of monazite was carried out in a thermostat at a temperature of 220 °C for 24 h using concentrated HCl acid with Teflon inserts inside a stainless-steel jacket. Separation of U and Pb was performed using a modified T.E.Krogh technique. For quantitative determination of Pb and U, a mixed 208Pb-235U tracer was applied. Isotopic analysis of Pb and U was performed on a Triton TI multi-collector mass spectrometer (analyst N.G.Rizvanova, IPGG RAS) in a single filament mode on Re filaments, pre-heated for 30 min at a temperature of 2000±50 °C. For the measurements, a silica gel emitter mixed with H3PO4 was used. Mass fractionation factors, determined for Pb from measurements of the NBS standard SRM-982 and for U from measurements of a natural sample, amounted to 0.1 and 0.08 % per atomic mass unit, respectively. Blank contamination did not exceed 50 pg Pb and 10 pg U. Data processing was carried out using the PbDAT and ISOPLOT programs (author K.Ludwig). When calculating the age, the uranium decay constants from [26] were used. Corrections for common lead were introduced according to model values. All errors are reported at the 2σ level.

Computer modeling of phase equilibria was performed using the PERPLE_X v.7.19 program [27] (updated up to 2024) with a database of thermodynamic data for minerals and solid solutions of biotite, plagioclase, chlorite, garnet, spinel, orthopyroxene, white micas, chloritoid, staurolite, cordierite, ilmenite in the MnTiNCKFMASH (MnO–TiO2–Na2O–CaO–K2O–FeO–MgO–Al2O3–SiO2–H2O–CO2) hp62ver system [28]. The thermodynamic description of melt properties was done according to the paper [29].

The material for determining the compositions of the protoliths of the supracrustal rocks of the Chupa Formation included 100 samples; in addition to the authors' own data, data from the works of O.I.Volodichev and O.S.Sibelev were used (all of them can be provided upon request). These data were divided by cluster analysis and using various diagrams into five groups, which were then analyzed in detail using thermodynamic calculations of metamorphic mineral formation conditions. The analysis of the chemical composition of 152 samples of rock-forming minerals was also used. U-Pb dating of migmatites by monazite was performed for two samples of migmatized garnet-kyanite gneiss (from the whole rock).

Petrochemical characteristics of the studied rocks

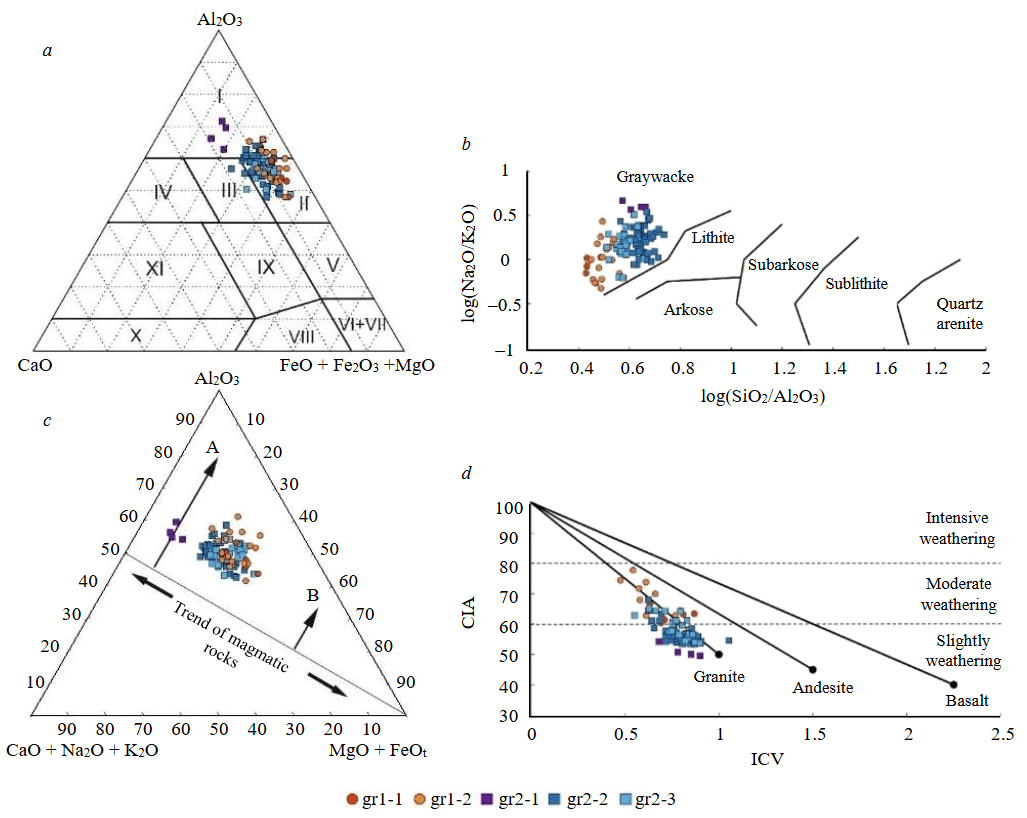

The available data on the chemical composition of the rocks of the Chupa Formation, based on cluster analysis, were preliminarily divided into five groups (gr1-1 – gr2-3) and considered on diagrams. On the N.P.Semenenko* classification diagram, most of the figurative composition points are concentrated in the upper part of field II, which corresponds to ferromagnesian aluminosilicate protoliths (Fig.2, a). A smaller number of points are located in the fields of alkaline-earth aluminosilicate (III) and aluminosilicate (I) protoliths. At the same time, within the field of aluminosilicate protoliths (I), two rock groups are distinguished – one with an elevated aluminum content (gr2-1), and the other (gr1-2, gr2-2) tends towards the compositions of ferromagnesian aluminosilicate protoliths (II).

On the classification diagram [30], which is used to determine sediment maturity, the compositions of the Chupa Formation gneisses fall into the field of immature sediments – greywackes (Fig.2, b). Weak and moderate sediment maturity is also illustrated by the Al2O3 – (CaO + Na2O + K2O) – (FeOt + MgO) diagram (Fig.2, c), proposed in the work [31]. The compositions of these samples form a compact field between vectors A and B, elongated towards the apex of the triangle in the direction of increasing weathering intensity. This indicates uneven chemical weathering of a wide spectrum of terrigenous material in the source area. A small part of the points forms a trend in the direction of composition change of acid igneous rocks (A) that underwent chemical weathering; at the same time, this could also be the result of a high degree of migmatization of the gneisses [32].

The Index of Compositional Variability (ICV) varies in the range from 0.5 to 1.1 and reflects the presence of clastic material of varying degrees of sedimentary maturity in the metasedimentary rocks (Fig.2, d, Table 1). The figurative points on the CIA-ICV diagram [31, 32] tend towards the lower part of the granite trend, while the points of aluminous gneisses have a higher ICV value and tend towards the central granite line. The Chemical Index of Alteration (CIA) indicates that the rocks of the Chupa Formation generally had weakly and moderately weathered source materials. The high-alumina gneisses, containing a noticeable amount of kyanite, have CIA values from 60 to 78 and are slightly more mature than the garnet-biotite gneisses, in which this index ranges from 50-60 (Fig.2, d).

Fig.2. Position of figurative points representing chemical compositions of Chupa Formation gneisses on classification diagrams: а – А–С–FM; b – log(Na2O/K2O) – log(SiO2/Al2O3) [30]; c – Al2O3 – (CaO + Na2O + K2O) – (MgO + FeOt), mol. % [31] (arrows indicate compositional trends during chemical weathering of acidic (A) and basic (B) igneous rocks); d – CIA-ICV [31, 33]

Field names according to N.P.Semenenko: I – aluminosilicate; II – iron-rich-magnesian aluminosilicate; III – alkali-earth-aluminosilicate, orthoseries; IV – calcic-aluminosilicate; V – aluminous-magnesian-iron-rich-siliceous; VI – iron-rich-siliceous; VII – magnesian ultramafic; VIII – alkali-earth-Al-poor, ultramafic orthoseries; IX – alkali-earth-aluminous, mafic othoseries; X – calc-carbonate; XI – aluminous-calcic

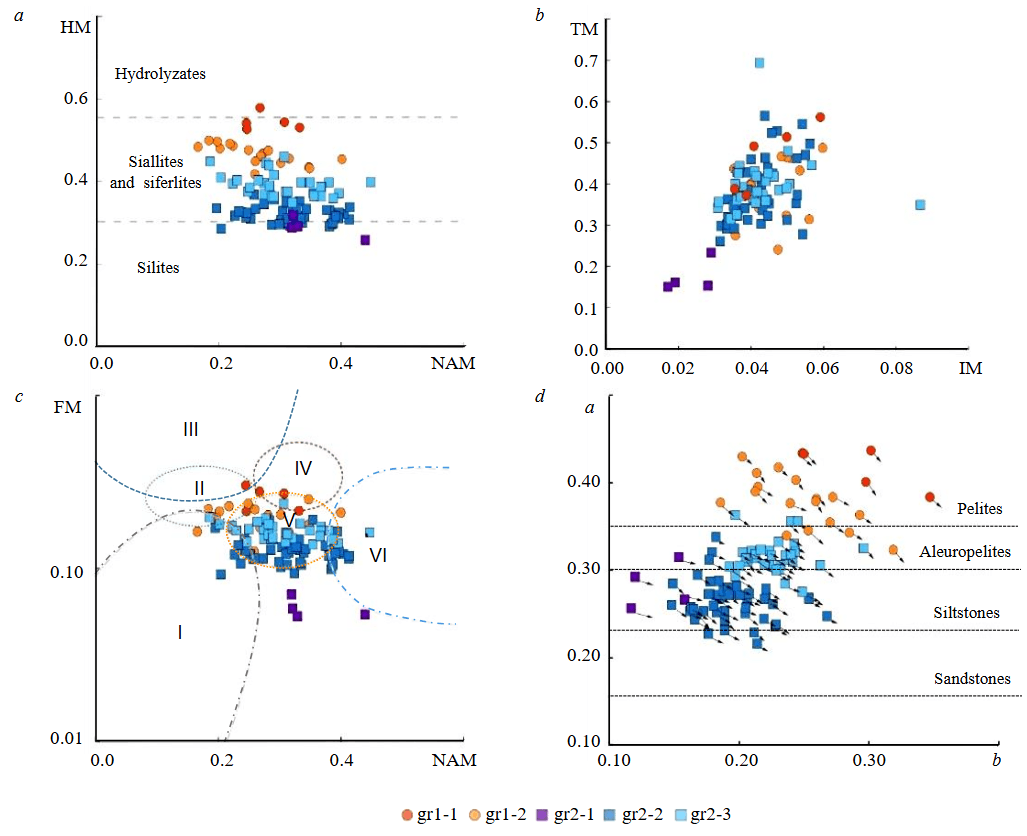

The compositions of the studied rocks, based on the values of the hydrolyzate modulus (HM) [34], belong to siallites and siferlites (the latter predominate), as well as silites (Fig.3, a). In half of the samples, the MgO content exceeds or is close to 3 wt.%, which allows them to be considered as pseudosiallites and pseudosilites. The negative correlation on the HM-NAM diagram (Fig.3, a) and the positive correlation in the coordinates of TM-IM (Fig.3, b), along with AlkM > 1 and elevated values of IM and HM, indicate the primary erosion of igneous rocks with a noticeable admixture of basic-composition pyroclastics (volcaniclastics) [34].

Table 1

Petrochemical indices of Chupa Formation gneisses

|

Group of gneisses |

N analyses |

HM |

АМ |

FM |

ТМ |

AlkM |

NAM |

IM |

ASM |

||||

|

gr1-1 |

5 |

0.52-0.58 |

0.32-0.37 |

0.21-0.30 |

0.04-0.06 |

0.54-1.04 |

0.25-0.33 |

0.37-0.56 |

4.5-5.9 |

||||

|

gr1-2 |

17 |

0.27-0.36 |

0.27-0.36 |

0.13-0.25 |

0.03-0.06 |

0.60-2.69 |

0.17-0.40 |

0.24-0.49 |

3.8-7.0 |

||||

|

gr2-1 |

4 |

0.26-0.32 |

0.22-0.27 |

0.05-0.07 |

0.02-0.03 |

3.68-4.63 |

0.32-0.44 |

0.15-0.23 |

5.0-6.8 |

||||

|

gr2-2 |

46 |

0.28-0.35 |

0.18-0.27 |

0.09-0.19 |

0.03-0.05 |

0.87-3.42 |

0.20-0.41 |

0.26-0.57 |

3.0-6.3 |

||||

|

gr2-3 |

29 |

0.36-0.44 |

0.23-0.31 |

0.15-0.19 |

0.03-0.09 |

0.62-3.18 |

0.19-0.45 |

0.32-0.45 |

3.5-7.6 |

||||

|

Group of gneisses |

N analyses |

Petrochemical parameters after A.N.Neelov [35] |

CIA |

ICV |

|||||||||

|

a, at. qty |

b, at. qty |

n, at. qty |

k, at. qty |

||||||||||

|

gr1-1 |

5 |

0.38-0.44 |

0.25-0.35 |

0.12-0.18 |

0.38-0.55 |

61-67 |

0.63-0.87 |

||||||

|

gr1-2 |

17 |

0.32-0.42 |

0.19-0.32 |

0.10-0.19 |

0.20-0.55 |

55-78 |

0.48-0.88 |

||||||

|

gr2-1 |

4 |

0.26-0.31 |

0.12-0.16 |

0.10-0.17 |

0.12-015 |

50-54 |

0.68-0.91 |

||||||

|

gr2-2 |

46 |

0.22-0.32 |

0.14-0.25 |

0.10-0.19 |

0.15-0.40 |

51-69 |

0.63-1.05 |

||||||

|

gr2-3 |

29 |

0.27-0.36 |

0.19-0.30 |

0.10-0.18 |

0.17-0.51 |

51-65 |

0.66-0.90 |

||||||

Notes. Petrochemical modules: hydrolyzate HM – [(Al2O3 + TiO2 + FeOt + MnO)/SiO2]; aluminum-silica АМ – [Al2O3/SiO2]; femic FM – [(FeOt + MnO + MgO)/SiO2]; titanium ТМ – [TiO2/Al2O3]; alkaline AlkM – [Na2O/K2O]; normalized alkalinity modulus NAM – [(Na2О + K2О)/Al2O3]; iron IM – [(FeOt + MnO)/(TiO2 + Al2O3)]; total alkalinity ASM – [Na2O + K2O] [34]. Petrochemical parameters: a – Al/Si, b – (Fe2+ + Fe3+ + Mn + Ca + Mg)/1000, vector length n – K + Na, vector slope k – K/(K + Na) [35]. CIA – [Al2O3/(Al2O3 + CaO + Na2O + K2O)]∙100 [31], IСV – [(Fe2O3 + K2O + Na2O + CaO + MgO + TiO2)/Al2O3 [32]. Median values of compositions are given in parentheses.

On the FM-NAM diagram [34], designed for the separation of clayey deposits, most of the rocks are localized in the field of essentially chloritic clay compositions with a subordinate role of Fe-hydromicas. The more leucocratic gneisses fall into the uncertainty field. A part of the compositions is located in the field of predominantly kaolinitic clays, while the high-alumina gneisses tend towards the upper part of field (V) and enter the overlap fields – montmorillonite-kaolinite-illitic clays (Fig.3, c).

To determine the nomenclatural classification of the rocks, the classification diagram of A.N.Neelov [35], developed for metamorphosed sedimentary-volcanogenic formations, was used. On the diagram (Fig.3, d), parameter a – the alumina modulus – reflects two mechanisms of material differentiation: the intensity of chemical weathering and granulometric sorting; parameter b characterizes the overall melanocratic index of the rocks; and the alkalinity of the rocks is expressed by vectors n and k. The main cluster of points is concentrated in the field of siltstones and aleuropelites. Fewer compositions fall into the field of sandstones and pelites. In accordance with this, it can be concluded that the distribution of rock composition points is related to a greater extent to the granulometric differentiation of the material. It should be noted that a part of the points (gr2-1) is characterized by a gentler slope of vector k (0.12-0.15) compared to other rock groups (0.20-0.55) due to the predominance of Na2O over K2O. At the same time, these compositions are shifted leftward along the b axis relative to the majority of other compositions due to the lower content of FeO and MgO in the rock. It is also characteristic that a part of the points (gr1-1) is shifted rightward along the b axis because of the higher content of FeO and MgO in the rock, while this rock group has the maximum values of parameter k (0.38-0.55) due to the predominance of K2O over Na2O.

Fig.3. Compositional plots of studied metasedimentary rocks from the Chupa Formation on modulus diagrams

FM-NAМ (а), ТМ-IМ (b) и HМ-NAМ (c) [34], a-b diagram (d)

Clay composition fields: I – predominantly kaolinitic clays; II – montmorillonite-kaolinite-hydromica clays; III – essentially chloritic clays with subordinate Fe-hydromicas; IV – chlorite-hydromica clays; V – chlorite-montmorillonite clays; VI – predominantly hydromica clays with significant feldspar admixture

Petrographic features of the Chupa gneisses

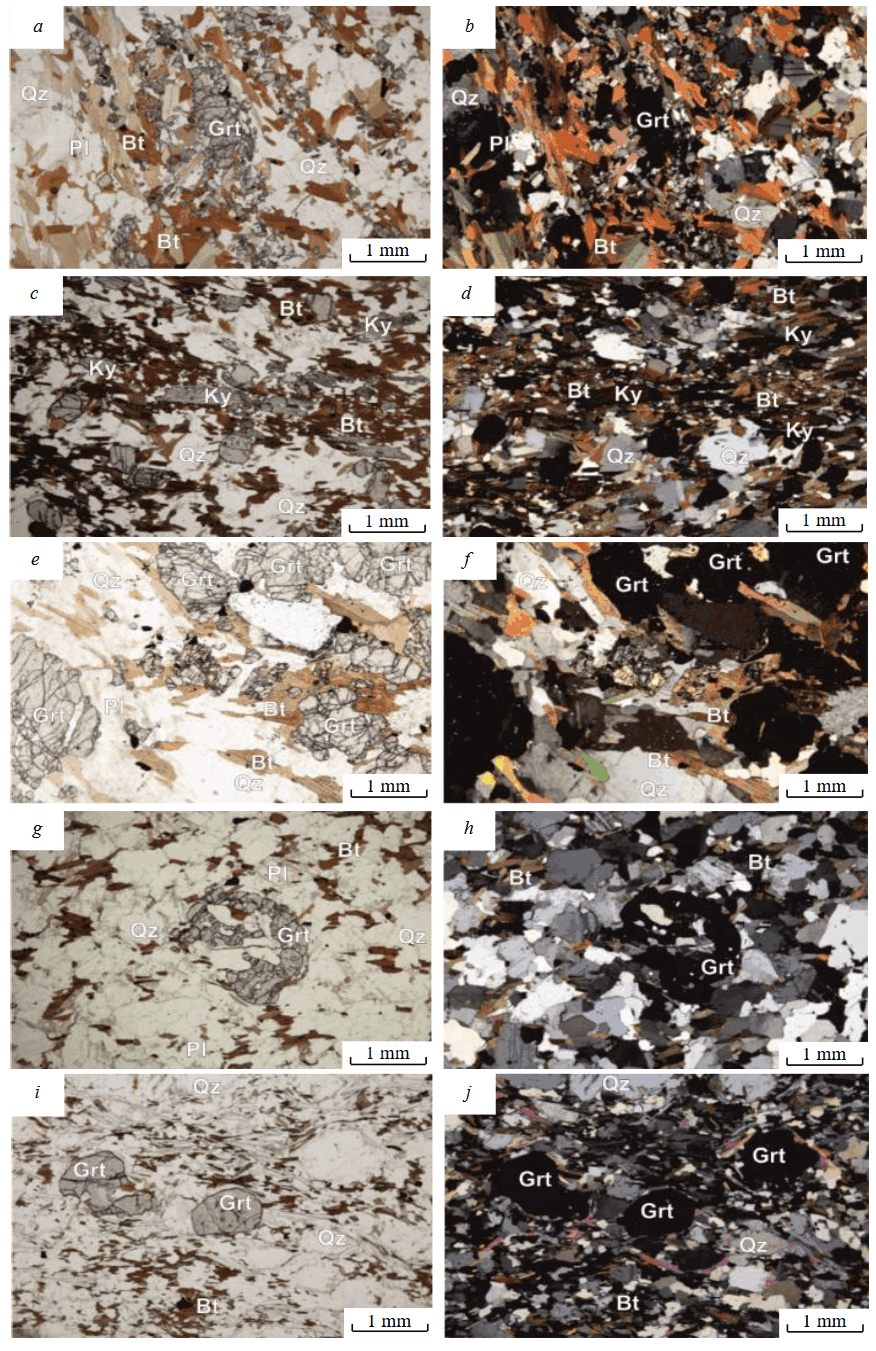

Based on petrographic composition, four varieties of gneisses are confidently distinguished: garnet-biotite; kyanite-garnet-biotite, with the kyanite content ranging from single grains to 20 vol.%; leucocratic essentially quartz-plagioclase gneisses, in which mafic minerals (garnet, biotite, single grains of kyanite) do not exceed 10 vol.%; and muscovite-bearing gneisses, in which muscovite is in association or paragenesis with the described mafic minerals. All gneisses are characterized by both fine-grained and coarse-grained porphyrolepidogranoblastic, lepidogranoblastic, and granoblastic structures, as well as massive, more often banded textures (Fig.4). As a rule, porphyroblasts are represented by garnet, much more rarely by kyanite. Garnet has a pyrope-almandine composition (Alm60-73Py17-30Grs6-9Sps1-4)* and contains inclusions of both matrix minerals – quartz, biotite,

kyanite – and accessory phases – apatite, monazite, zircon, rutile. Garnet grains exhibit retrograde zoning – from the core to the rim of the grains, the content of the pyrope component decreases and the proportion of the almandine component increases.

Fig.4. Petrographic characteristics of rocks from the Chupa Formation: kyanite-garnet-biotite gneiss(а, b);

garnet-kyanite-biotite gneiss (c, d); coarse-grained kyanite-garnet-biotite gneiss(e, f), kyanite partially replaced by staurolite; leucocratic garnet-biotite gneiss (g, h); garnet-muscovite-biotite gneiss (i, j).

Photographs on the left were taken in plane-polarized light (PPL), on the right – in cross-polarized light (XPL)

Biotite belongs to magnesian varieties (Mg# 0.58-0.67) with a predominance of the phlogopite component in its composition and contains 2.6-4.0 wt.% TiO2. It is the second most common and second largest in grain size, as a rule, tends to melanocratic layers, exhibits pleochroism in brown colors, has practically no secondary alterations, and contains inclusions of zircon.

Plagioclase (An 23-30 %) often has polysynthetic twins and is located in leucocratic layers, being locally subjected to secondary alterations. Quartz occurs together with plagioclase, its grain sizes vary widely, and fine grains or rims adjacent to garnet and around kyanite grains are often observed.

Kyanite most often occurs in paragenesis with garnet and biotite; its association with the boundaries of layers is observed, which, most likely, emphasizes the heterogeneity of the primary protolith of the metasedimentary rock. During retrograde changes, this early metamorphic kyanite is replaced by staurolite. Along with metamorphic kyanite, kyanite with reaction rims of muscovite and quartz is found in migmatites. Kyanite porphyroblasts may contain inclusions of quartz, biotite, apatite, and rutile.

Muscovite is the second most significant mica in the Chupa gneisses, occurs in association with biotite, and develops along cracks in kyanite, more rarely being present in the rock matrix. The muscovite content varies strongly and sometimes reaches 30 vol.%. Potassium feldspar is practically absent in the studied rocks but has been found as inclusions in garnet and in some types of migmatite leucosomes.

Migmatization in the studied gneisses is manifested unevenly – rocks are encountered across a wide spectrum – from those unaffected by migmatization to highly migmatized ones, containing up to 50-70 vol.% leucosomes. The thickness of the leucosomes varies from a few millimeters to a few centimeters. They are represented mainly by plagioclase-quartz aggregates with single grains of biotite, muscovite, and garnet; potassium feldspar varieties with muscovite are also occasionally found.

Determination of PT conditions of migmatization

The metamorphic mineral parageneses observed in the studied rocks are well reproduced during computer modeling of mineral formation in the PERPLE_X program (Fig.5). The paragenesis consisting of garnet, plagioclase, kyanite, biotite, and rutile occupies areas of high-temperature amphibolite and granulite facies of medium- to moderately high-pressure metamorphism on these diagrams. The best results for mineral formation during computer modeling were obtained using a carbonic-aqueous fluid with a ratio СО2:Н2О = 0.2:0.8. With a greater amount of carbonic acid in the fluid, carbonate minerals (dolomite, ankerite, etc.) become widespread, which does not correspond to natural observations.

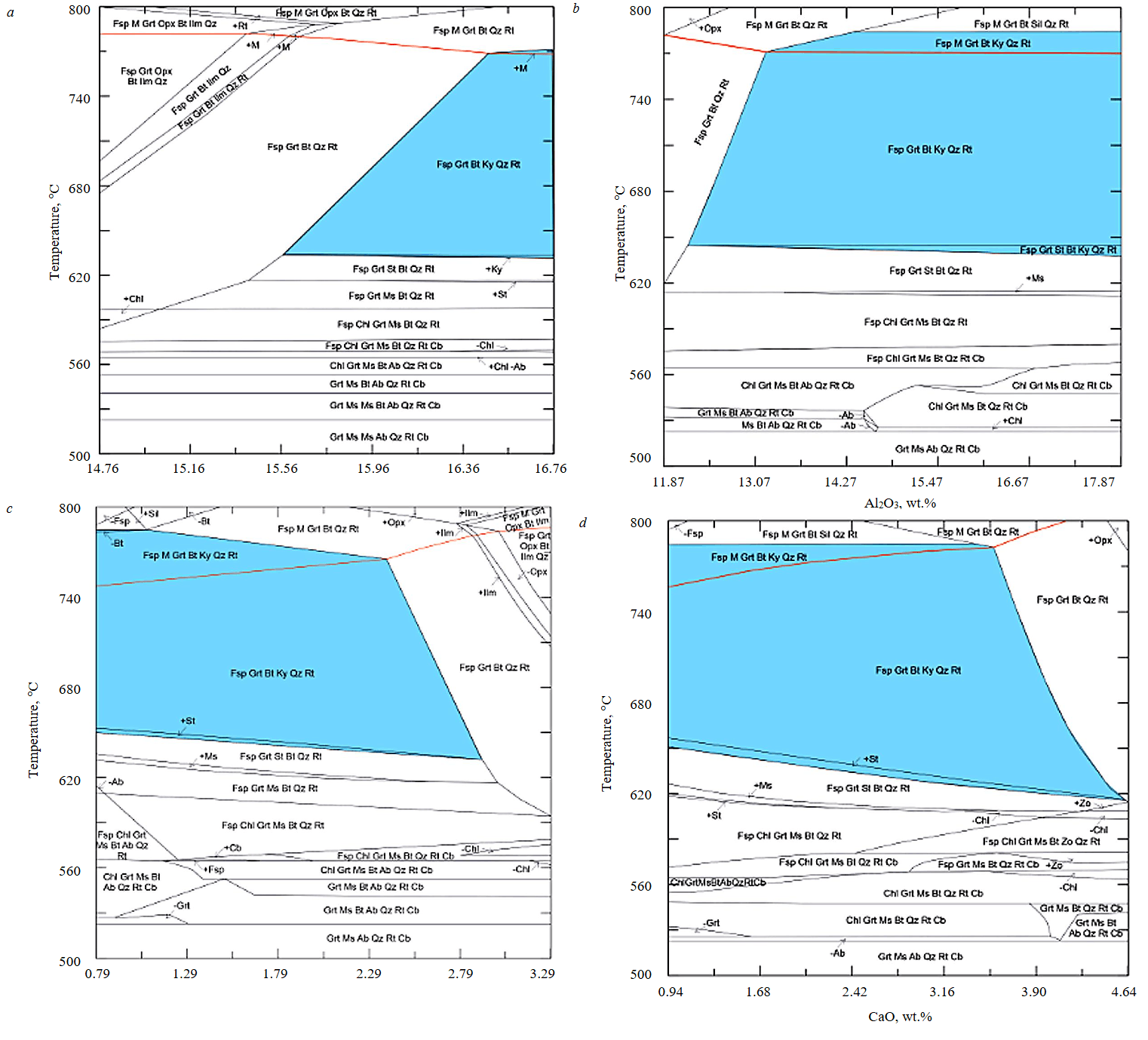

The kyanite-free mineral paragenesis is also adequately reproduced by modeling if the protoliths are characterized by an elevated calcium content (Fig.5, b). This can be demonstrated using binary diagrams with varying amounts of a series of components (Fig.6). The diagrams show that kyanite-bearing mineral parageneses, at the same PT parameters, can arise only in relatively high-alumina protoliths but with a low calcium content. While the first condition is obvious – alumina is the main component of kyanite – the increase in calcium content involves an increase in the amount of plagioclase in the metamorphic rock, which leads to the complete consumption of alumina during the formation of this feldspar. An additional condition to the specified parameters is the excess of the sum of alkalis (Na2O + K2O) over CaO in the protolith. However, in the considered examples, favorable protolith compositions for kyanite formation were those in which the sum of FeO + MgO contents usually did not exceed 10 wt.% (in rare cases, slightly higher).

The initial temperature of appearance of the granitic melt in rocks of different composition differs somewhat on average and indicates the possibility of anatectic leucosome formation in the temperature range of 680-730 °C. The most important parameter, besides the protolith composition, affecting the position of the granite liquidus line is the proportion (activity) of water in the metamorphic fluid. For example, a decrease in the molar fraction of water from 1 to 0.6 in a carbonic-aqueous fluid causes an increase in the initial melting temperature of the Chupa gneisses by 50-70 °C.

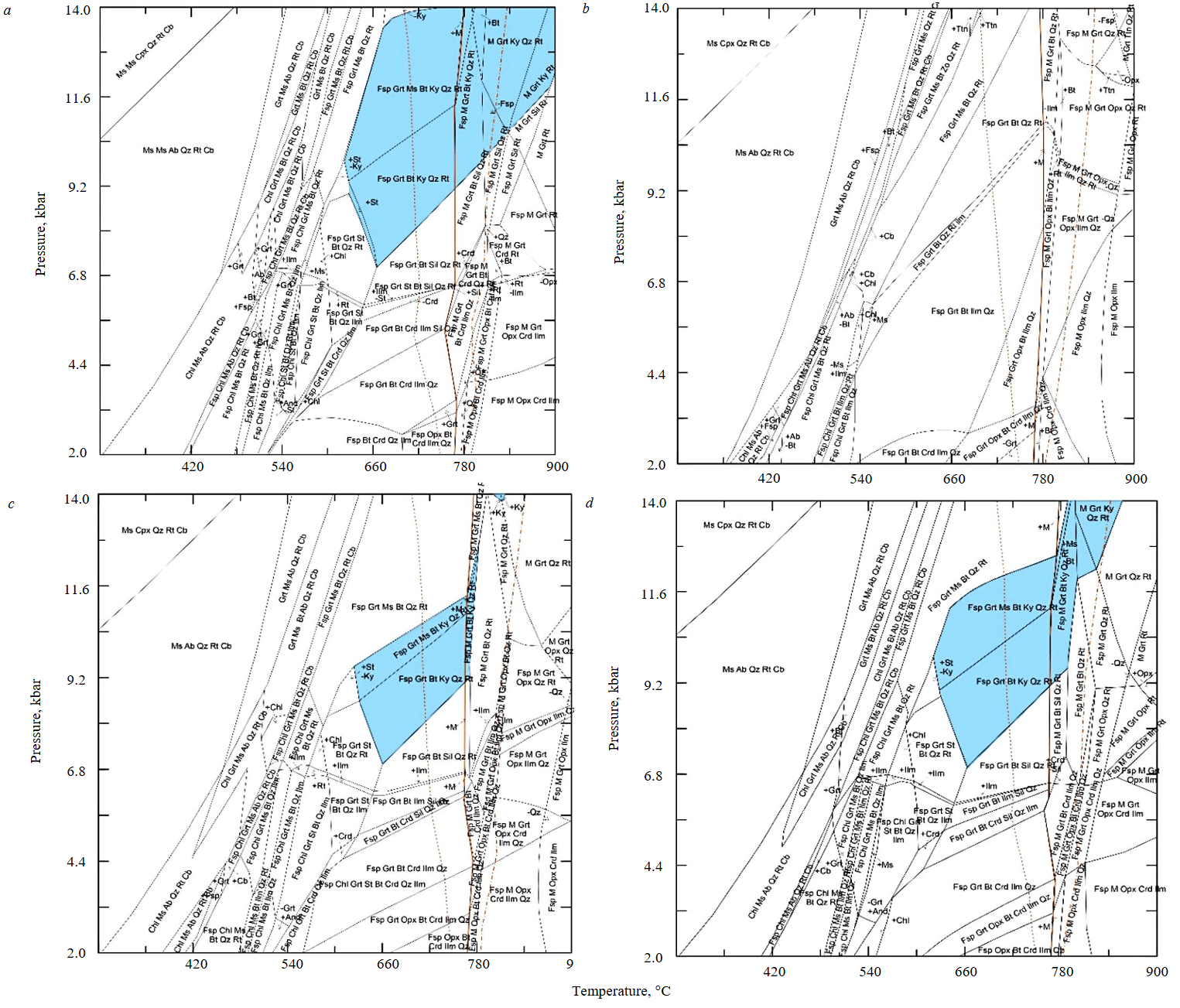

Fig.5. PT phase equilibrium diagrams calculated by Gibbs free energy minimization for rocks of the Chupa Formation: gneisses (gr1-2), having a protolith with compositions transitional between groups I (aluminosilicate) and II (ferromagnesian aluminosilicate) with elevated Fe and Mg contents (а); gneisses (gr2-1) with a protolith – aluminosilicate (I), but with a high CaO content (b); gneisses with protolith compositions between groups I and II, belonging to siltstones (gr2-2) (c) and aleuropelites (gr2-3) (d).

The field of presence of kyanite-bearing mineral parageneses is shown in blue. The position of the granite liquidus at different CO2:H2O ratios in the fluid is indicated by red lines: dashed line – CO2 = 0.0, solid line – CO2 = 0.2, dash-dotted line – CO2 = 0.4

Fig.6. Binary phase diagrams “Temperature – Composition”, calculated by the Gibbs free energy minimization method to determine compositions favorable for the appearance of kyanite with variations in the protolith contents of Al2O3 (a, b) and CaO (c, d).

The field of presence of kyanite-bearing mineral parageneses is shown in blue, the position of the granite liquidus at a fluid ratio of CO2:H2O = 0.2:0.8 is indicated by a red line

U-Pb dating of monazite

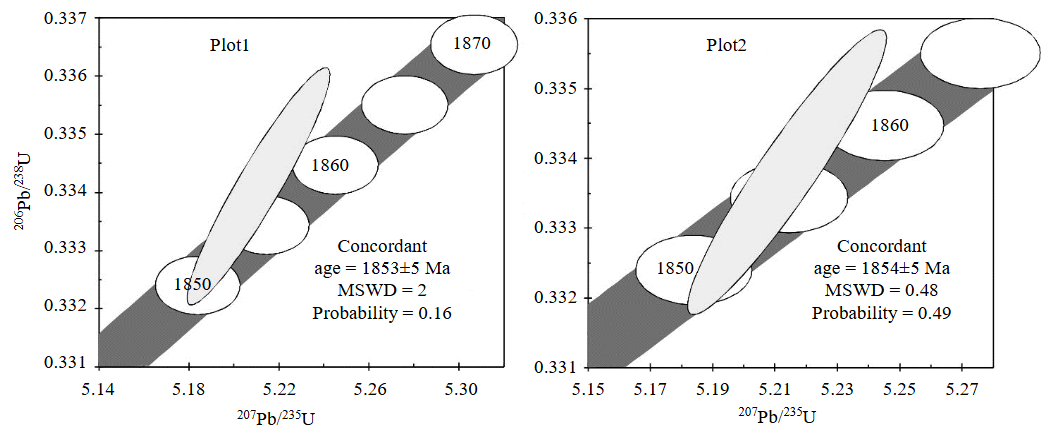

Isotopic U-Pb analysis of monazite from two samples (Plot1 and Plot2, see Fig.1) of migmatized garnet-kyanite-plagioclase gneiss is presented in Table 2. The figurative points of monazite on the Concordia diagram (Fig.7) are located with a slight deviation from the concordia curve of the two isotopic subsystems of the U-Pb system, which indicates the absence of its disturbance after the crystallization of the studied minerals.

Table 2

Results of U-Pb isotopic studies of monazite

|

Sample |

N grains |

206Pbа |

207Pbb |

208Pbb |

207Pb |

206Pb |

Th |

Rho |

Age, Ma |

Concordant |

MSWD/ Р |

||

|

206Pb |

207Pb |

207Pb |

|||||||||||

|

Plot1 |

8 grains |

4290 |

0.11313 |

2.2409 |

5.211 |

0.3341 |

6.2 |

0.94 |

1858.0 |

1854.4 |

1850.3 |

1853±5 |

2/0.16 |

|

Plot2 |

12 grains |

7590 |

0.11329 |

2.1725 |

5.214 |

0.3338 |

6.0 |

0.94 |

1856.9 |

1855.0 |

1852.9 |

1854±5 |

0.48/0.48 |

The concordant age values were for sample Plot1 1853±5 Ma, MSWD = 2 with a concordance probability of 0.16, and for sample Plot2 – 1854±5 Ma, MSWD = 0.48 with a probability of 0.49. Given the practical identity of the calculated age values, as well as their overlap within analytical error, the age of monazites from the two samples is taken as 1854±5 Ma.

Discussion

Metamorphic mineral parageneses in the studied rocks of the Chupa Formation have a sufficiently wide stability field in temperature and pressure coordinates. Data from previous studies (e.g. [19]) indicate that mineral parageneses corresponding to peak high-pressure granulite facies conditions are preserved in leucosomes of amphibolites, and their retrograde transformations occurred under medium- and high-temperature amphibolite facies conditions of high pressure. However, it remains unclear to which time of the endogenous evolution of the rocks these PТ parameters relate, since in the migmatites, these authors dated only Archean-age zircons, while younger (e.g., Paleoproterozoic) zircons were not detected in the samples. This is strange, since Paleoproterozoic processes are very intensely manifested in the BMB [16, 23, 37], which is confirmed by numerous geochronological studies [38-40]. In particular, in the rocks of the Voche-Lambina area in the northwestern part of the BMB, a leucosome with east-dipping transpressional lineations has an age of 1898±2 Ma and is associated with Paleoproterozoic collisional events [38]. Further south, in the Chupa-Loukhi area, the last collisional metamorphism and migmatization took place between 1840 and 1875 Ma (according to U-Pb SIMS studies of zircon [41]). Taking these geochronological data into account, a suggestion has been made [38] that within the BMB, the collision of the Archean Kola and Karelian cratons led to the formation of a regional complex of shearing zones (plastic shear flow) under amphibolite-facies metamorphic conditions, which was accompanied by migmatization of the rocks [38, 41,42]. Metamorphism does not always lead to noticeable migration of chemical elements in rocks, as follows from a number of works on structures adjacent to the Chupa Formation [43, 44].

Fig.7. Concordia diagram for two monazite samples from garnet-kyanite-plagioclase gneiss of the Chupa Formation.

Age values are calculated at 2σ confidence level

Metamorphic conditions corresponding to moderate or elevated pressures of the amphibolite facies are very characteristic both for the BMB and for structures directly adjacent to the belt. In particular, PT parameters of moderate-pressure amphibolite facies metamorphism have been established in intrusions of peridotites, as well as acidic and intermediate metavolcanics aged 1923-1926 Ma of the Kaskama structure of the Inari terrane, located north of the Lapland Granulite Belt [45]. Paleoproterozoic progressive amphibolite facies metamorphism at T = 625-660 °C and P = 7-9 kbar is also described in the rocks of the Korvatundra structure underlying the Lapland Granulite Belt [46].

The compositions of most protoliths of the Chupa gneisses turned out to be favorable for the formation of kyanite. The key factor determining the appearance of kyanite in the studied rocks is the elevated Al2O3/CaO ratio in the protoliths, which must be at least 5:1 with a content of the sum of alkalis (Na2O + K2O) exceeding the content of CaO. In such protoliths, kyanite forms both above and below the water-saturated solidus temperature. This determines the widespread presence of this mineral both in migmatized varieties and in gneisses that do not contain leucosomes.

Judging by the ICV values in the range of 0.5-1.1, the protoliths contained clastic material of varying sedimentary maturity. Weakly and moderately weathered rocks of granitic composition could have served as the protoliths.

Zones of gentle foliation and shearing (plastic shear flow), associated with the formation of gently dipping (5-30°) subhorizontal or northwest-striking thrusts, are considered as an important benchmark of the Paleoproterozoic stage of evolution of the BMB [38, 39, 42]. S.Yu.Kolodiazhnyi also believes that the widely developed, gently dipping thrust zones within the BMB formed as a result of the emplacement of the Porya Guba granulite protrusion [47]. Based on the geological relationships of Paleoproterozoic dikes and metagabbro masses with sheared rocks, as well as geochronological data obtained from metamorphic rocks in zones of gentle shearing and foliation, it is suggested that these zones formed around 1855 Ma [39].

According to U-Pb dating of titanite and rutile [37], during the period from approximately 1.94 to 1.82 Ga, the rocks of the BMB experienced slow cooling. The last metamorphic event 1900-1800 Ma, which led to the resetting of the U-Pb system in titanites and local zircon growth, was associated with zones of migmatization and pegmatite formation, where the most intensive circulation of aqueous-alkaline fluids is assumed [37, 41].

The obtained data on the PT parameters of metamorphism and the timing of migmatization in the Chupa Formation should be considered as one of the stages of Paleoproterozoic tectono-thermal activity, reaching conditions of partial rock melting in intensity. The place of this event in the overall sequence of tectonic events in the region, as well as the nature of the involvement of geological structures formed by that time, requires further study. Possibly, in the tectonic scenario explaining the evolution of Paleoproterozoic endogenous events within the BMB, one should take into account processes associated with the formation of the Svecofennian orogen and, accordingly, the Svecofennian orogeny.

Conclusion

The conducted studies of the mineral and petrographic composition, together with the determination of the lithochemical parameters of the rocks of the Chupa Formation (BMB), U-Pb dating of metamorphic monazite, and petrogenetic modeling, allow us to draw the following conclusions:

- The PT metamorphic parameters and the U-Pb isotopic age of 1854±5 Ma for monazite from migmatized gneisses of the Chupa Formation correspond to one of the stages of Paleoproterozoic tectono-thermal activity in the BMB. The nature of this activity in the context of the development and formation of large structures of the Belomorian region in the Paleoproterozoic requires further study.

- The metamorphic mineral parageneses, consisting of garnet, plagioclase, kyanite, biotite, and rutile, are well reproduced during computer modeling of mineral formation in the field of high-temperature amphibolite and granulite facies of medium- to moderately high-pressure metamorphism.

- The key factor determining the appearance of kyanite in the Chupa rocks is the elevated Al2O3/CaO ratio, which must be at least 5:1 at a weight content of alkalis, the sum (Na2O+ K2O) of which must exceed CaO.

- Judging by the value of the ICV parameter, the protoliths contained clastic material of varying sedimentary maturity. Such protoliths could have been weakly and moderately weathered granites.

References

- Mingguo Zhai, Xiyan Zhu, Yanyan Zhou et al. Continental crustal evolution and synchronous metallogeny through time in the North China Craton. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences. 2020. Vol. 194. N 104169. DOI: 10.1016/j.jseaes.2019.104169

- Emo R.B., Kamber B.S. Evidence for highly refractory, heat producing element-depleted lower continental crust: Some implications for the formation and evolution of the continents. Chemical Geology. 2021. Vol. 580. N 120389. DOI: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2021.120389

- Touret J.L.R., Santosh M., Huizenga J.M. Composition and evolution of the continental crust: Retrospect and prospect. Geoscience Frontiers. 2022. Vol. 13. Iss. 5. N 101428. DOI: 10.1016/j.gsf.2022.101428

- Marimon R.S., Hawkesworth C.J., Dantas E.L. et al. The generation and evolution of the Archean continental crust: The granitoid story in southeastern Brazil. Geoscience Frontiers. 2022. Vol. 13. Iss. 4. N 101402. DOI: 10.1016/j.gsf.2022.101402

- Sakyi P.A., Kwayisi D., Nunoo S. et al. Crustal evolution of alternating Paleoproterozoic belts and basins in the Birimian terrane in southeastern West African Craton. Journal of African Earth Sciences. 2024. Vol. 220. N 105449. DOI: 10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2024.105449

- Wen-Bin Xue, Shao-Cong Lai, Yu Zhu et al. Generation of Neoproterozoic granites of the Huangling batholith in the northern Yangtze Block, South China: Implications for the evolution of the Precambrian continental crust. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences. 2025. Vol. 277. N 106395. DOI: 10.1016/j.jseaes.2024.106395

- Alekseev V.I. Deep structure and geodynamic conditions of granitoid magmatism in the Eastern Russia. Journal of Mining Institute. 2020. Vol. 243, p. 259-265. DOI: 10.31897/PMI.2020.3.259

- Marin Yu.B., Smolensky V.V., Beskin S.M. Classification of Rare-Metal Alkali Granites. Geology of Ore Deposits. 2024. Vol. 66. N 7, p. 905-913. DOI: 10.1134/S1075701524700132

- Lehmann B. Formation of tin ore deposits: A reassessment. Lithos. 2021. Vol. 402-403. N 105756. DOI: 10.1016/j.lithos.2020.105756

- Yong-Fei Zheng, Peng Gao. The production of granitic magmas through crustal anatexis at convergent plate boundaries. Lithos. 2021. Vol. 402-403. N 106232. DOI: 10.1016/j.lithos.2021.106232

- Qiong-Xia Xia, Meng Yu, Er-Lin Zhu et al. Two generations of crustal anatexis in association with two-stage exhumation of ultrahigh-pressure metamorphic rocks in the Dabie orogen. Lithos. 2023. Vol. 446-447. N 107146. DOI: 10.1016/j.lithos.2023.107146

- Shaoji Yang, Yanru Song, Haijin Xu et al. Paleoproterozoic ultrahigh-temperature metamorphism and anatexis of the pelitic granulites in the Kongling terrane, South China. Precambrian Research. 2024. Vol. 414. N 107591. DOI: 10.1016/j.precamres.2024.107591

- Guangyu Huang, Jinghui Guo, Richard Palin. Phase equilibria modeling of anatexis during ultra-high temperature metamorphism of the crust. Lithos. 2021. Vol. 398-399. N 106326. DOI: 10.1016/j.lithos.2021.106326

- Haobo Wang, Shuyun Cao, Junyu Li et al. High-pressure granulite-facies metamorphism and anatexis of deep continental crust: New insights from the Cenozoic Ailao Shan–Red River shear zone, Southeast Asia. Gondwana Research. 2022. Vol. 103, p. 314-334. DOI: 10.1016/j.gr.2021.10.010

- Guangyu Huang, Hao Liu, Jinghui Guo et al. Partial melting mechanisms of peraluminous felsic magmatism in a collisional orogen: An example from the Khondalite belt, North China craton. Journal of Metamorphic Geology. 2024. Vol. 42. Iss. 6, p. 817-841. DOI: 10.1111/jmg.12774

- Early Precambrian of the Baltic shield. Ed. by V.A.Glebovitskii. Saint-Petersburg: Nauka, 2005, p. 711 (in Russian).

- Glebovitskii V.A., Sedova I.S., Larionov A.N., Berezhnaya N.G. Isotopic Timing of the Magmatic and Metamorphic Events at the Turn of the Archean and Proterozoic within the Belomorian Belt, Fenno-Scandinavian Shield. Doklady Earth Sciences. 2017. Vol. 476. Part 2, p. 1143-1146. DOI: 10.1134/S1028334X1710004X

- Volodichev O.I. Belomorian Complex of Karelia. Geology and Petrology. Leningrad: Nauka, 1990, р. 245 (in Russian).

- Slabunov A.I., Azimov P.Ya., Glebovitskii V.A. et al. Archaean and Palaeoproterozoic Migmatizations in the Belomorian Province, Fennoscandian Shield: Petrology, Geochronology, and Geodynamic Settings. Doklady Earth Sciences. 2016. Vol. 467. Part 1, p. 259-263. DOI: 10.1134/S1028334X16030077

- Myskova T.A., Glebovitskii V.A., Miller Yu.V. et al. Supracrustal Sequences of the Belomorian Mobile Belt: Protoliths, Age, and Origin. Stratigraphy and Geological Correlation. 2003. Vol. 11. N 6, p. 535-549.

- State Geological Map of the Russian Federation, Scale 1:200000. Izdanie 2-e. Seriya Karelskaya. List Q-36-XV, XVI (Loukhi). Obyasnitelnaya zapiska. Moscow: Moskovskii filial “VSEGEI”, 2021, p. 109 (in Russian).

- Ruchev A.M. On the protolith of the North Karelian gneisses of the Chupa Formation, Belomorian Complex. Geologiya i poleznye iskopaemye Karelii. Petrozavodsk: Karelskii nauchnyi tsentr RAN, 2000. Iss. 2, p. 12-25 (in Russian).

- Bibikova E.V., Borisova E.Yu., Drugova G.M., Makarov V.A. Metamorphic History and Age of Aluminous Gneisses of the Belomorian Mobile Belt on the Baltic Shield. Geokhimiya. 1997. N 9, p. 883-893 (in Russian).

- Drugova G.M. Peculiarities of the early Precambrian metamorphism in Eastern and Western parts of the Belomorsky folded belt (Baltic shield). Zapiski Vserossiiskogo mineralogicheskogo оbshchestva. 1996. Vol. 125. N 2, p. 24-38 (in Russian).

- Skublov S.G., Azimov P.Ya., Li X.-H. et al. Polymetamorphism of the Chupa шддшеу of the Belomorian Mobile Belt (Fennoscandia): Evidence from the Isotope-Geochemical (U-Pb, REE, O) Study of Zircon. Geochemistry International. 2017. Vol. 55. N 1, p. 47-59. DOI: 10.1134/S0016702917010098

- Steiger R.H., Jäger E. Subcommission on geochronology: Convention on the use of decay constants in geo- and cosmochronology. Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 1977. Vol. 36. Iss. 3, p. 359-362. DOI: 10.1016/0012-821X(77)90060-7

- Connolly J.A.D. Multivariable Phase Diagrams: An Algorithm Based on Generalized Thermodynamics. American Journal of Science. 1990. Vol. 290. Iss. 6, p. 666-718. DOI: 10.2475/ajs.290.6.666

- Holland T.J.B., Powell R. An improved and extended internally consistent thermodynamic dataset for phases of petrological interest, involving a new equation of state for solids. Journal of Metamorphic Geology. 2011. Vol. 29. Iss. 3, p. 333-383. DOI: 10.1111/j.1525-1314.2010.00923.x

- White R.W., Powell R., Holland T.J.B. et al. New mineral activity–composition relations for thermodynamic calculations in metapelitic systems. Journal of Metamorphic Geology. 2014. Vol. 32. Iss. 3, p. 261-286. DOI: 10.1111/jmg.12071

- Pettijohn F.J., Potter P.E., Siever R. Sand and Sandstone. Springer-Verlag, 1972, p. 634.

- Nesbitt H.W., Young G.M. Early Proterozoic climates and plate motions inferred from major element chemistry of lutites. Nature. 1982. Vol. 299. Iss. 5885, p. 715-717. DOI: 10.1038/299715a0

- Yurchenko A.V., Baltybaev S.K., Volkova Yu.R., Malchushkin E.S. The Mineralogical Composition, Metamorphic Parameters, and Protoliths of Granulites from the Larba Block of the Dzhugdzhur–Stanovoy Fold Area. Russian Journal of Pacific Geology. 2024. Vol. 18. N 2, p. 130-149. DOI: 10.1134/S181971402402009X

- Cox R., Lowe D.R., Cullers R.L. The influence of sediment recycling and basement composition on evolution of mudrock chemistry in the southwestern United States. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 1995. Vol. 59. Iss. 14, p. 2919-2940. DOI: 10.1016/0016-7037(95)00185-9

- Yudovich Ya.E., Ketris M.P. Principles of lithogeochemistry. Saint-Petersburg: Nauka, 2000, p. 479 (in Russian).

- Neelov A.N. Petrochemical classification of metamorphosed sedimentary and volcanic rocks. Leningrad: Nauka, 1980, p. 100 (in Russian).

- Warr L.N. IMA–CNMNC approved mineral symbols. Mineralogical Magazine. 2021. Vol. 85. Iss. 3, p. 291-320. DOI: 10.1180/mgm.2021.43

- Bibikova E., Skiöld T., Bogdanova S. et al. Titanite-rutile thermochronometry across the boundary between the Archaean Craton in Karelia and the Belomorian Mobile Belt, eastern Baltic Shield. Precambrian Research. 2001. Vol. 105. Iss. 2-4, p. 315-330. DOI: 10.1016/S0301-9268(00)00117-0

- Daly J.S., Balagansky V.V., Timmerman M.J., Whitehouse M.J. The Lapland–Kola orogen: Palaeoproterozoic collision and accretion of the northern Fennoscandian lithosphere. European Lithosphere Dynamics. Geological Society of London, 2006. Vol. 32, p. 579-598. DOI: 10.1144/GSL.MEM.2006.032.01.35

- Kozlovskii V.M., Travin V.V., Savatenkov V.M. et al. Thermobarometry of Paleoproterozoic Metamorphic Events in the Central Belomorian Mobile Belt, Northern Karelia, Russia. Petrology. 2020. Vol. 28. N 2, p. 183-206. DOI: 10.1134/S0869591120010038

- Dokukina K.A., Konilov A.N., Bayanova T.B. et al. Metamorphosed Plagiogranite Veins In Salma Eclogites, Belomorian Eclogite Province. Precambrian Research. 2024. Vol. 400. N 107248. DOI: 10.1016/j.precamres.2023.107248

- Bibikova E.V., Bogdanova S.V., Glebovitsky V.A. et al. Evolution of the Belomorian Belt: NORDSIM U-Pb Zircon Dating of the Chupa Paragneisses, Magmatism, and Metamorphic Stages. Petrology. 2004. Vol. 12. N 3, p. 195-210.

- Balaganskii V.V. Main stages of tectonic development of the Northeastern Baltic Shield in the Paleoproterozoic: Avtoref. dis. … d-ra geol.-mineral. nauk. Saint Petersburg: Institut geologii i geokhronologii dokembriya RAN, 2002, p. 32 (in Russian).

- Krylov D.P., Klimova E.V. Origin of carbonate-silicate rocks of the Porya Guba (the Lapland-Kolvitsa Granulite Belt) revealed by stable isotope analysis (δ18O, δ13C). Journal of Mining Institute. 2024. Vol. 265, p. 3-15.

- Salimgaraeva L.I., Skublov S.G., Berezin A.V., Galankina O.L. Fahlbands of the Keret archipelago, White Sea: the composition of rocks and minerals, ore mineralization. Journal of Mining Institute. 2020. Vol. 245, p. 513-521. DOI: 10.31897/PMI.2020.5.2

- Vrevsky A.B., Kuznetsov A.B., Lvov P.A. Age and Stratigraphic Position of a Supracrustal Complex (Kaskama Block, Inari Terrane, Northeastern Kola–Norwegian Region of the Fennoscandian Shield). Doklady Earth Sciences. 2023. Vol. 511. Part 2, p. 645-651. DOI: 10.1134/S1028334X23600950

- Nitkina E.A., Belyaev O.A., Dolivo-Dobrovolskii D.V. et al. Metamorphism of the Korvatundra Structure of the Lapland – Kola Orogen (Arctic Zone of the Fennoscandian Shield). Russian Geology and Geophysics. 2022. Vol. 63. N 4, p. 503-518. DOI: 10.2113/RGG20214404

- Kolodiazhnyi S.Yu. Paleoproterozoic structural-kinematic evolution of the South-East Baltic Shield. Moscow: GEOS, 2006, p. 332 (in Russian).