Constructed Floating Wetlands – a phytotechnology for wastewater treatment: application experience and prospects

- 1 — Ph.D., Dr.Sci. Chief Researcher Polar-Alpine Botanical Garden-Institute of N.A.Avrorin, Federal Research Centre, Kola Science Centre of the RAS ▪ Orcid

- 2 — Ph.D. Researcher Institute of North Industrial Ecology Problems, Kola Science Centre of the RAS ▪ Orcid

- 3 — Ph.D. Leading Researcher Institute of North Industrial Ecology Problems, Kola Science Centre of the RAS ▪ Orcid

Abstract

The article is devoted to the actively developing area of wastewater treatment – Constructed Floating Wetlands (CFW, floating bioplatforms). The paper explores the creation history and operational experience of CFW in Russia and abroad. It describes the designs and preferred compositions of substrates and plants for creating phytomodules, paying special attention to the use of natural minerals and the selection of local macrophyte plant species. The CFW technology is suitable for treating various types of wastewater, including inorganic effluents from mining enterprises. The research examines the results of applying phytotechnology for wastewater treatment for pollutants (total nitrogen and phosphorus, organic matter, suspended particles, heavy metals, sulphates, boron, etc.). The article shows successful practices of using CFW for acidic drainage effluents, which are the most challenging for phytotechnology application. The study identifies key factors affecting pollutant removal efficiency – water depth, flow rate, coverage area, aeration, and temperature. The research presents methods to enhance the depth of water treatment at low temperatures. It also notes the positive impact of floating bioplatforms on the condition of water bodies where they are located. The study provides cost estimates for applying CFW technology for wastewater treatment and gives recommendations based on the experience of implementing the technology at a settling pond of a mining enterprise in the Murmansk Region.

Funding

The study was conducted under the research projects FMEZ-2025-0046, FMEZ-2025-0044, FMEZ-2024-0012.

Introduction

Mining industry is one of the rapidly developing sectors of the Russian economy, and all enterprises in this field are recognized as facilities that have a negative impact on the environment. Their responsibilities include approving standards for maximum permissible discharge of pollutants into water bodies. Quarry, shaft, drainage waters coming from the mining enterprises are dominated by mineral components and nitrogen compounds (for quarry wastewater using explosives), while domestic wastewater in industrial areas contains organic matter. Water is disposed to treatment facilities (separate or combined), and then, through settling ponds, into natural water bodies or recycled water supply for enterprise needs. The impact of insufficiently treated effluents results in changes in the hydrological and temperature regimes, increased water turbidity, bottom silting, and restructuring of the species composition of microbiota, flora, and fauna [1]. In 2022, the Information and Technical Reference on Best Available Technologies for Wastewater Treatment (ITS NDT 8-2022) was introduced. It recognizes biosorption, ozonation, ferrate oxidation, aerobic and anaerobic microbiological treatment, coagulation/flocculation, and membrane distillation as the most promising wastewater treatment methods. Phytotechnologies are highlighted as a direction that, as international experience showed, besides their important environmental significance, confirmed their high economic efficiency in water treatment systems. In 2000, the International Water Association issued the main design and operation document for phytotreatment systems [2]. National water treatment standards are developed based on it, considering local features [3, 4].

Phytotechnologies are actively being implemented worldwide, as evidenced by a number of review articles published in international periodicals on water treatment of various types [5, 6], removal of metals and metalloids using bioplatforms [7], and increasing process intensification [8]. The scientific literature extensively covers the experience of operating phytoremediation systems in cold climates (Finland, Canada, Norway, Northern China) [9-11].

In Russia, among the articles in the Scientific Electronic Library over the past five years and related to the industrial-scale implementation of phytotechnologies, only two are devoted to treating quarry waters for nitrogen at a mining enterprise in the Murmansk Region [12] and desalinating drainage waters in irrigation systems in Kalmykia [13]. Although these technologies have not yet gained wide distribution in Russia, the development of methods for their design and operation in various climatic zones of the country and for a wide range of pollutants attracts the attention of the scientific community [14, 15].

History of floating platforms development

A promising direction in phytotechnology is the creation of floating platforms. The scientific literature provides various names for this technology: Floating treatment wetland, Floating island, Ecological floating bed, Artificial floating island, Planted floating system bed, Vegetated floating island, Hydroponic root mat, Natural floating wetland, Constructed Floating Wetlands. In recent years, the most commonly used term is Constructed Floating Wetlands (CFW), which we will use in this text.

The methods of forming such vegetative structures have been known since ancient times, when countries suffering from regular flooding of fertile lands began to develop aquatic agricultural technologies (floating-bed agriculture). This method is still widely used in Bangladesh, India, Vietnam, Indonesia, Thailand, and the Philippines. It involves creating artificial floating islands for hydroponic cultivation of vegetable and cereal crops in long-term flooded areas [16, 17]. A distinctive feature of floating bioplatforms is the development of the root system in the aquatic environment, while the leaf biomass grows above the water surface. Easily decomposable remnants of aquatic plants – Eichhornia and Lémna – are used as substrate-soil substitutes. These plants are characterized by active accumulation of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium, thus simultaneously serving as bio-fertilizers.

The development of CFW technology initially took place within the framework of Constructed Wetlands (CW) technology, which emerged in Germany in the 1950s. However, CFW quickly evolved into an independent scientific field. The first report on the creation of CFW for water treatment came from Germany and was published in [18]. Although floating bioplatforms cannot technically be called “artificial wetlands”, the term remains widely used. This is because CFW combines water treatment mechanisms found in both natural and artificial wetlands (ponds) with freely floating vegetation [19]. The cost of CFW technology is significantly lower than CW, as it does not require the construction and maintenance of hydraulic structures. A detailed retrospective analysis of CW technology development, including CFW, was conducted in [20]. Research on hydroponic technologies (floating and non-floating (rooted) wetlands) and their differences from CW and biological treatment ponds was presented in [19].

In the late 1980s, CFW technology began to actively develop in China, the USA, and Japan [21], primarily for treating domestic and stormwater runoff. Further development focused on both improving and expanding the range of removable pollutants and combining with classical and modern water treatment technologies, leading to the development of hybrid systems [22].

Currently, the leading countries in implementing CW technologies are China, the USA, Germany, Japan, and Australia. For CFW technologies, the leaders are China and Pakistan [4].

Floating bioplatform structures

Due to the active implementation of nature-inspired technologies such as CFW for water treatment and landscape design, the USА company Floating Islands International launched industrial production of bioplatform frames made from recycled PET foam. More often, frames are constructed from scrap materials based on proprietary designs [23]. Ensuring the bioplatform frame buoyancy and the ability to combine separate modules into clusters are particularly important. PVC or polyethylene pipes, as well as bamboo stems, are used for this purpose [24]. There is experience in using 1.5-litre PET bottles as floats. The bioplatform base is made of foamed polymer plastics (polyurethane foam, polyethylene foam, polypropylene foam, recycled PETE). The most rational area of individual modules is 2 m2, but the literature provides options for frames ranging from 0.025 to 50 m2 [24]. Modules are connected using natural or synthetic fibres [25] or special straps.

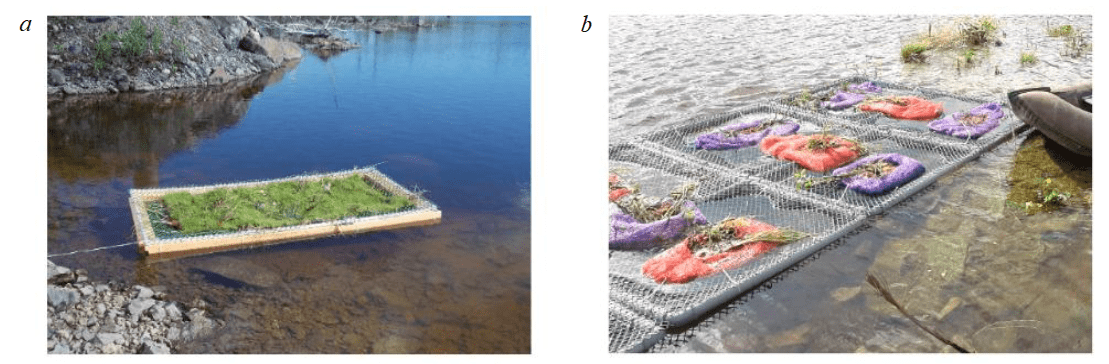

Figure 1 shows a patented design of a floating bioplatform phytomodule [26] used for testing quarry water treatment technology at the settling pond of AO Olkon (Olenegorsk, Murmansk Region) [12]. The structure includes a rectangular base frame constructed from plastic pipes 1 and 2 m long, with diametres of 20 or 50 mm, connected at right angles with elbows. A plastic grid with 3×3 cm cell size, covering an area of 2 m2, is placed on the frame. This serves as a bio-loading platform for pre-grown carpet-like grass turf (Fig.1, a) or phytomats [27] (Fig.1, b), both planted with marsh plants [28].

Fig.1. General view of the floating bioplatform phytomodule with marsh plants planted in the turf (a) and phytomates (b)

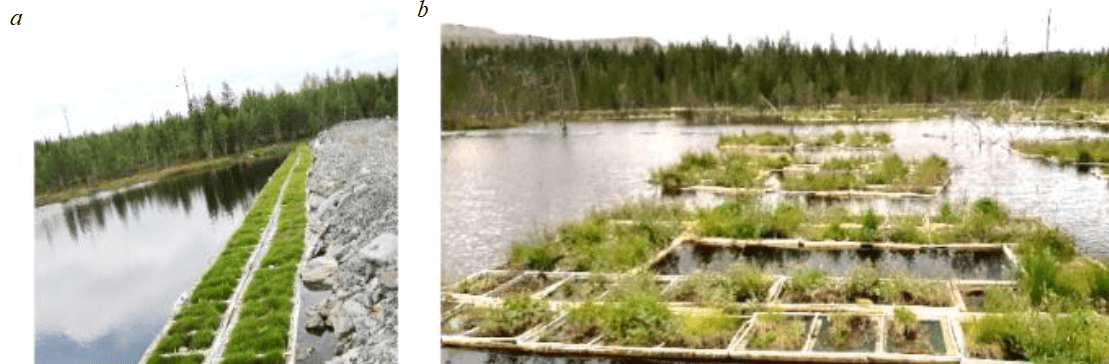

The formed rows of phytomodules were attached to the bank of the reservoir using cables with carabiners, while clusters were installed in the centre of the reservoir and held in deep-water areas using an anchor consisting of a bag filled with stones weighing approximately 15 kg. Details of the connection between phytomodules and methods of strengthening the structure are provided in the patent [26]. Fig.2 shows how the phytomodules were installed on the water surface.

Fig.2. Installation of phytomodules in a row (a) and clusters (b) in the deep-water part of the reservoir

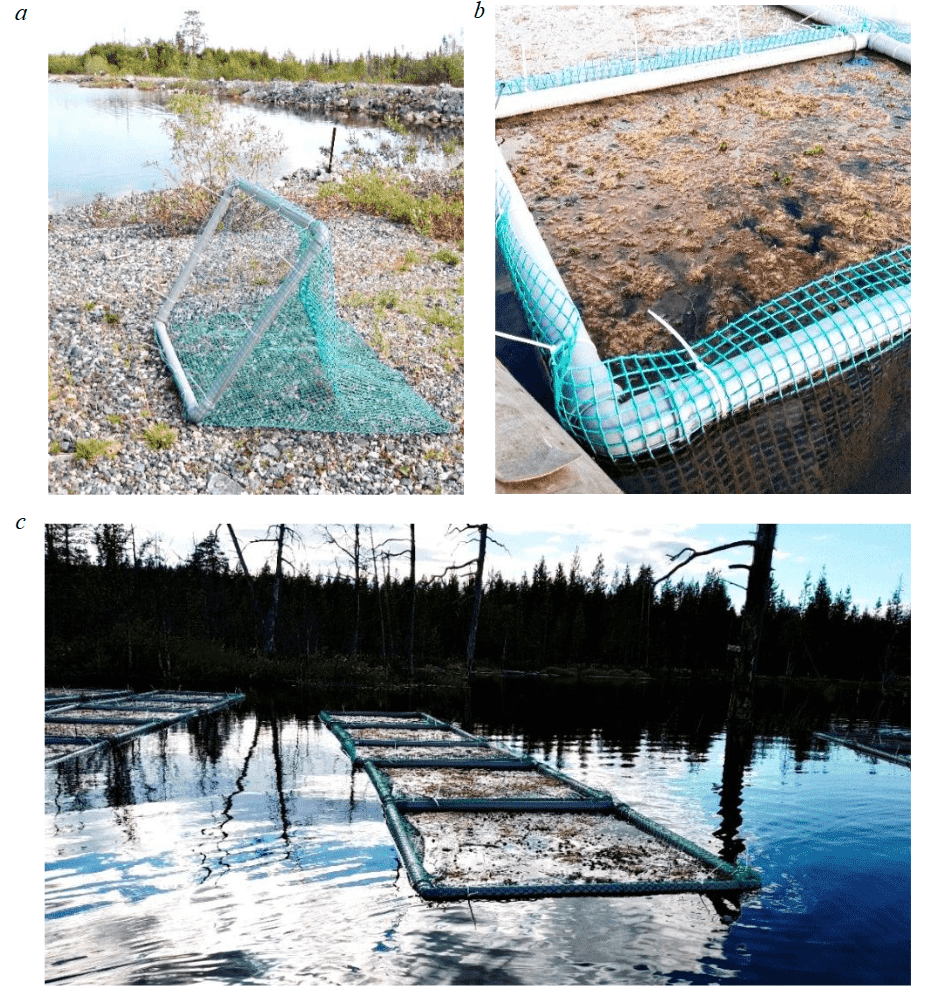

In addition to floating bioplatforms, phytoplants [29] were used in open areas of the reservoir with depths to 2 m. The design of these consists of a rigid base made of buoyant material, a mesh bed part, and an anchor (Fig.3).

Fig.3. Floating plant beds installed in deep-water sections of the reservoir: a – general view of the phytomodule; b – plant bed filled with local aquatic plant species; c – plant beds installed in a row configuration

In CFW technologies, when selecting substrates for plants, the following material parameters are considered: porosity, capillary, and fertilizing value. The most commonly used materials include coconut and bamboo fibre, compost, activated carbon, biochar, vermiculite, perlite, and plastic granules. Recom mendations for substrate selection and optimization are outlined in a review article [30]. The primary requirement for these materials is minimal impact on water pH and non-toxicity to microbiota and plants. The authors of [28] used Vipon brand thermo-vermiculite of various fractions, widely employed in other hydroponic technologies, as well as fresh and bedding wood sawdust.

The selection of plants in CFW technology is of fundamental importance, as their ability to rapidly grow biomass and accumulate pollutants in it largely determines the degree of water treatment. Equally important is the presence of aerenchyma in the root system – an air-containing tissue composed of cells with large intercellular spaces filled with air [18]. This tissue, commonly found in aquatic and marsh plants, ensures the necessary level of gas exchange under anaerobic conditions.

In favourable climatic conditions, the following plants are most commonly used in water treatment for various pollutants: common bulrush (Schoenoplectus (Scirpus) lacustris), sedge (Carex sp.), water lettuce (Pistia stratiotes), broad-leaved cattail (Typha latifolia), duckweed (Lémna minor), soft rush (Juncus effusus), common reed (Phragmites australis), common water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes). Pilot studies by M.A.Pashkevich et al. [31] revealed the active transport of Zn, Cu, and Mn in broad-leaved cattail and common arrowhead (Alisma plantago-aquatica), indicating hyperaccumulation of heavy metals by macrophyte plants.

In northern conditions, based on existing experience, the following plants can be recommended for use as biological loading for floating bioplatforms: red fescue (Festuca rubra), grey foxtail (Elytrigia intermedia), perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne), timothy grass (Phleum pratense) – for forming carpet-like grass turf [28]; white-winged marsh plant (Calla palustris), marsh trefoil (Menyanthes trifoliata), goat willow (Salix caprea), tea-leaved willow (S. phylicifolia), creeping buttercup (Ranunculus repens), coltsfoot (Tussilago farfara), various sedges, narrow-leaved cotton-grass (Eriophorum angustifolium), cotton-grass (E. vaginatum), Scheuchzer’s cotton-grass (E. scheuchzeri), marsh cinquefoil (Comarum palustre), sphagnum mosses (Sphagnum spp.), marsh horsetail (Equisetum palustre), stream horsetail (E. fluviatile) – native bog species for additional planting in the created vegetation cover[27]. In open water areas with shallow depths (to 1 m) in backwaters, it is possible to use goat willow and tea-leaved willow, marsh marigold (Cáltha palústris), creeping buttercup (Ranunculus repens), floating hook-moss (Warnstofia fluitans), floating pondweed (Potamogeton natans), duckweed (Fig.4), common water-pepper (Hippuris vulgaris), marsh horsetail and stream horsetail.

Fig.4. Using duckweed to swamp a pond’s backwater

It should be noted that the selection of plant assortment was based on many years of experience in their application. Preference was given to relatively tolerant to technogenic pollution (including biogenic elements) perennial macrophytes (hydro- and hydatophyte plants) growing in the Murmansk Region, excluding interspecific conflicts and intraspecific competition, capable of vegetative reproduction under pollution conditions, accumulating large biomass, and performing filtration (settling of suspended solids), absorption (absorption of biogenic elements and organic substances), accumulation (accumulation of certain metals and organic substances), oxidative (enrichment of water with oxygen), and detoxification (conversion of toxic compounds into non-toxic ones) functions.

A significant role in CFW technology is played by the symbiosis of plants with microorganisms (bacteria, algae, fungi), especially in the rhizosphere (root) zone. To enhance treatment efficiency, measures are taken to create an artificial biofilm – a consortium of bacteria, fungi, algae, and protozoa united by extracellular polymeric compounds on a solid carrier. The main polymeric components are polysaccharides, proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids. The biodiversity in this community is higher than in water, which increases biomass, microbocenosis stability, and the surface area of CFW [18]. The biofilm is particularly effective in removing suspended solids, phosphorus, and nitrogen, mitigating the negative impact of uneven water flow, temperature, and anthropogenic load on the bioplatform plants [32].

As carriers for biofilm, both natural and synthetic materials are used: plant residues, basalt fibre, zeolites, activated carbon, borosilicate glass, vermiculite, perlite, natural fibres, clinoptilolite (natural ion exchanger), polyethylene, polypropylene, polyurethane. Methods for forming artificial biofilm in water treatment technologies are detailed in [33]. In pilot experiments, the surface area of the biofilm increases through the use of bio-ball garlands filled with porous material. The appearance and method of attaching bio-balls to the root zone of plants are presented in [34].

Among the variety of water types successfully treated with CFW technologies, the following are distinguished: domestic wastewater, quarry water, stormwater (surface runoff, street and roadway wash-offs), agricultural wastewater (livestock and poultry farming), food industry plant effluents, oil-contaminated water, wastewater from textile and sugar processing industries, eluates (effluents from solid domestic waste landfills), drainage water, process water.

The development of CFW technology is based on data from laboratory, pilot (microcosm), and field studies. For practical implementation, field experiment results are undoubtedly more valuable, but they are described much less frequently in scientific literature compared to laboratory and pilot research findings. For the first time, a detailed review of comparing water treatment efficiencies obtained through various types of experiments within the framework of CFW technology application was conducted by Chinese experts in [21]. Out of an extensive body of scientific articles published in English and Chinese, only 28 are devoted to field experiment results (in situ research), with 11 of them relating to hybrid systems (e.g., those with submerged plants and forced aeration). The highest efficiency of CFW phytotechnology was noted for removing all forms of nitrogen (ammonium, nitrate, nitrite, organic), phosphate phosphorus and organically bound phosphorus, as well as for reducing biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) and chemical oxygen demand (COD) indicators in water. Research on treating faecal-contaminated water have also delivered encouraging results [22].

Efficiency of water treatment by floating bioplatforms

Scientific literature documents the results of water treatment for a wide range of pollutants using CFW.

Total nitrogen and phosphorus

Total nitrogen in water exists in ammonium, nitrate, nitrite, and organic forms. There are three ways to treat water for nitrogen: denitrification, sedimentation, and bioaccumulation by aquatic plants and microorganisms. Denitrification (reduction of nitrates to molecular nitrogen) removes to 80 % of nitrogen, while sedimentation and bioaccumulation account for a combined maximum of 20 % [21]. To enhance denitrification, authors recommend increasing the area of the rhizosphere zone and ensuring optimal water retention time in the treated water body. The degree of phosphorus removal with CFW varies from 5 to 88 % [18], with sorption by biofilm and sedimentation recognized as the main extraction mechanisms.

Organic pollutants

High organic matter content in water, as a labile carbon source, leads to uncontrolled algal growth. When organic matter decomposes under bacterial action, a large amount of oxygen is consumed, which causes the death of fish and other aquatic organisms. Organic matter is removed during water treatment through direct absorption by bacteria, algae, and higher plants, transformation of high-molecular compounds into simpler ones with lower molecular weight under the influence of microorganisms, adsorption of hydrophobic organic compounds on suspended particles or biofilm, followed by sedimentation as bottom deposits.

Suspended matter

Suspended particles increase water turbidity, which reduces the availability of solar radiation for bacteria, macrophytes, and benthic organisms. Suspended particles affect the survival rate of fish fry and the viability of zooplankton. Suspended solids are typically inorganic particles about 2 µm in size but can also have organic origins (algae, bacteria, and their remains). Since suspended particles have no nutritional value, they are not directly absorbed by plants or microorganisms. Instead, they sediment in the water layer between the bioplatform surface and bottom deposits, as well as on plant roots [21].

Heavy metals

Heavy metals (HM) enter water bodies through industrial discharges and runoff from road surfaces. These pollutants primarily appear in suspended form, with only a small portion in dissolved form, which can be directly absorbed by plants through interaction between HM ions and functional groups of the cell wall. High mineralization and multicomponent composition of incoming waters reduce the depth of treatment due to mutual influence of ions. The efficiency of suspended particle absorption depends on water composition, Eh, pH, HM concentration, nutrient availability, and physiological characteristics of plants included in the bioplatform. Examples of applying classical CW technologies for heavy metal removal are presented in [14], where treatment efficiency of up to 99 % is reported. There are few studies evaluating the effectiveness of HM extraction using CFW [35, 36]. Available results show that sedimentation of suspended forms in the rhizosphere zone and on biofilm is more effective than direct plant absorption. Therefore, it is recommended to focus on developing robust root mass and increasing biofilm surface area when implementing this technology.

Sulphates

A three-year experience in sulphate removal from drainage water in a settling pond is described in [37]. The field experiment was conducted in the Sudbury region (Canada), using soil as a substrate to create anaerobic conditions. The phytomodule included cattails, sedges, and rushes. The authors provided evidence of CFW effectiveness in reducing conditions at a low pH (5.0) and during prolonged operation of the bioplatform at low temperatures. The active development of sulphate-reducing bacteria was noted, which contributed to the reduction of sulphates to insoluble sulphides and their precipitation.

Boron

The problem of water ecosystem contamination with boron compounds is relevant in Chile, Turkey, New Zealand, and the USA due to territorial natural features. The boron concentration in drainage waters from boron-containing ore mines in Turkey reaches 2000 mg/l, while the average global surface water boron content is 0.1 mg/l [38]. The study shows that cattails, reeds, and duckweeds can act as boron hyperaccumulators when applied in CW systems. The main processes for boron removal in phytoremediation systems are sorption and plant bioaccumulation. To enhance boron removal efficiency, it is recommended to increase the content of organic matter and clay minerals in the substrate.

Selenium

Selenium is present in water in anionic form as selenates and selenites. A comprehensive assessment of selenium extraction efficiency using swampflower (the main macrophyte in floating wetlands in China) and Se concentration along the food chain was conducted in pilot experiments [39]. The results indicate the need to consider Se accumulation by all living organisms inhabiting the bioplatform.

Petroleum products and phenols

A comprehensive review of CFW technology application for petroleum- and phenol-contaminated water treatment is presented in [40]. The technology is recognized as highly effective both when using plants alone (primarily reeds and cattails) and with additional bacterial cultures. Experiments were mainly conducted in warm climate regions, but there are positive examples from northern regions as well. It is stated that rhizosphere microbiota of bioplatform plants handles petroleum contamination as effectively as introduced bacterial cultures. Therefore, measures to stimulate its growth are recommended.

When discussing the intricacies of implementing CFW technology, it is important to consider the modern direction of biosorption [41]. Both living biomass of plants and microorganisms, as well as detritus (which is often more effective), can serve as sorbents. Sorption is primarily due to the presence of oxygen-containing functional groups in living plant cells or detritus. Biosorption has extracellular, intracellular, and surface characteristics. Passive biosorption of pollutants occurs through interaction with the cell wall, which is a physicochemical process. Bioaccumulation, on the other hand, depends on intracellular metabolism and is therefore considered an active process.

When treating waters contaminated with heavy metals, biosorption plays a leading role. The sorption capacity of detritus is comparable to that of chemical sorbents, reaching hundreds of milligrams per gram. This method is particularly actively developed for extracting rare and dispersed elements, as well as precious metals, from wastewater.

Factors affecting the efficiency of CFW water treatment

Despite the fact that the main mechanisms of accumulation of various pollutants by plants are well known from numerous studies on phytoremediation and restoration of plant cover on technologically disturbed lands, it is quite difficult to predict the success of phytoremediation measures. The main factors affecting the efficiency of water treatment include water chemistry, water depth and flow rate, coverage area, aeration conditions, environmental conditions (water and air temperature, amount of precipitation).

Water chemistry is particularly important when selecting treatment methods, especially for wastewater from mining and industrial enterprises. On the one hand, effluents with extremely high or low pH values and elevated pollutant concentrations can have a phytotoxic effect on planted vegetation, leading to plant death [28, 42]. On the other hand, the joint presence of various pollutants in water can reduce treatment efficiency (compared to laboratory experiments) due to competition [21].

The optimal depth of the reservoir when applying CFW technology is considered to be 0.6-1.1 m, although experiments were conducted at various depths – from 0.25 to 3 m [43]. At shallow depths, plant roots of the bioplatform may touch the bottom sediments of the reservoir and gradually grow into the soil. Additionally, shallow depths reduce aeration efficiency, which decreases microbiological activity. With increasing water levels, plants may detach, potentially leading to their death. When selecting bioplatform plants, it is necessary to consider the maximum length of their root systems. In field trials at a settling pond for quarry waters, the depth reached 2 m during certain seasons due to increased discharge volumes [28]. This affected the efficiency of nitrate removal due to high water flow velocities and weak influence on the bioplatform plants (due to transit water flow). High flow velocities increase dissolved oxygen content in the water, which negatively affects denitrification [44]. Large water inflows contribute to biofilm washout or restructuring of its species composition [43]. Mathematical models were developed to simulate optimal flow rates and water retention times in the reservoir, an example of which is provided in [45].

To enhance treatment efficiency, the water surface coverage area is selected empirically to ensure proper oxygen levels in the water. A coverage exceeding 50 % may cause oxygen deficiency, while insufficient coverage results in low treatment efficiency. A 100 % coverage is only recommended in exceptional cases, such as nitrate removal, where denitrification (which occurs predominantly under anaerobic conditions) is the primary process [24]. At the settling pond of OA Olkon, 50 % of water surface was covered, amounting to 1300 m2. This was accomplished by creating 25 clusters with 19 floating phytomodules each, along with 150 additional phytomodules arranged in rows in shallow bank areas.

Dissolved oxygen content in water is crucial for root system development and biofilm formation. Aeration of the rhizosphere zone is important for removing organic matter and phosphate phosphorus but has an inhibitory effect on denitrification and sedimentation. Based on the target treatment objective, the oxygen regime in phytomodule-occupied zones is monitored and adjusted accordingly.

Climate conditions in areas where CFW systems are located can significantly impact the efficiency of water treatment. It is commonly believed that CFW technology is effective only during the summer period due to its reliance on microbiological activity, which decreases with lower temperatures. This is particularly relevant for nitrification-denitrification, which almost ceases at temperatures below 10 °C [11]. However, the removal of suspended solids is primarily a physical process driven by sedimentation and is therefore less dependent on temperature. High levels of BOD and COD reduction is observed in CFW systems in cold climate countries like Sweden and Canada. Denitrification is almost completely inhibited at temperatures below 10 °C. A study by Н.Postila et al. [46] evaluated the efficiency of total nitrogen removal in open-type phytoremediation systems in Finland, even during the summer period, showing only 12-14 % effectiveness (based on an assessment of 14 facilities).

Wetland treatment in cold regions using CFW (Talkeetna, Alaska) also showed insufficient effectiveness to meet regulatory standards [47]. However, a study conducted in Alberta (Canada) achieved high efficiency in municipal wastewater treatment [48]. The authors suggested that the positive results were due to maturation of the CFW system accompanied by enhanced interaction between plants and microorganisms, increased area of phytomodules, as well as addition of aeration under the CFW.

Relatively low water and air temperatures slow down plant growth and biomass accumulation. All macrophytes, such as reeds, cattails, and sedges, die off under prolonged exposure to low temperatures due to ice crystal formation in their cells and protein denaturation. Decaying biomass becomes a source of secondary water pollution.

To enhance water treatment efficiency during cold periods, the following methods are employed – introduction of biofilm carrier materials into the water body. Addition of labile organic matter sources (e.g., straw). Application of fibrous material suspensions and microbial mass in floating wetlands. The effectiveness of treatment directly correlates with microbial biodiversity within the system – the higher the diversity, the better the treatment even in cold conditions. Biotechnologies for cultivating cold-resistant macrophyte species, including genetic engineering, are actively developing. Particular attention is being paid to the study of benthic organisms, which contribute to the increased efficiency of CFW technology at low temperatures.

When assessing the impact of the environment, it is important to consider the projected consequences of climate change, as detailed in [21]: rising temperatures, changes in precipitation patterns, increased duration of dry periods. It is expected that warming will lead to an extension of the growth and development period for plants and the operational period of bioplatforms. However, increased precipitation intensity will reduce the water retention time in reservoirs with CFW and promote rapid nutrient leaching.

It should be emphasized that the results of field and pilot experiments differ significantly: under natural conditions, treatment efficiency decreases by an average of 20-30 %, and for phosphorus removal by more than 50 % compared to pilot studies. In some cases, secondary water pollution with nitrogen, phosphorus, and suspended solids occurs in situ.

Features of the floating bioplatform operation

Floating bioplatforms have a positive impact on the condition of water bodies where they are placed [21]. Since effective treatment requires a water surface coverage of at least 50 % by floating phytomodules, shading of the water surface occurs. This limits the development of phytoplankton and restructures its species composition – the proportion of blue-green algae, which cause water blooming, decreases. Thus, the application of CFW technology is recognized as promising in solving the problem of eutrophication of water bodies. However, an excessively high coverage area of the water surface with plant structures can lead to an extended period of water stratification, which must be monitored and regulated.

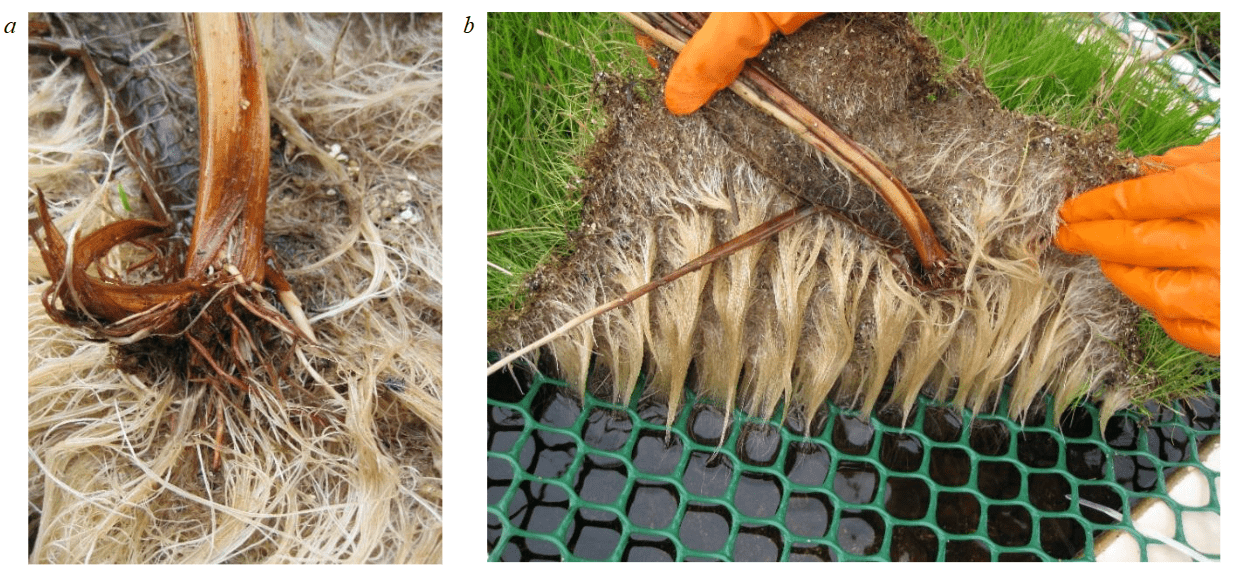

In [49], it is provided an example of the formation of an aquatic biocenosis in areas where CFW was applied on the Chicago River (USA), where the activity of zooplankton, insects, amphibians, reptiles, fish, and birds was noted in areas occupied by floating plant structures. Research [28] noted the active colonization of the floating bioplatform area by mosses and higher plants not included in the artificial phytocenosis, as well as the appearance of frogs, ducks, waders, hares, otters, and mice. The condition of the plant phytomodules observed in this study at the quarry water settling pond in 2024 is shown in Fig.5, 6.

The efficiency of water treatment for most pollutants largely depends on the power of root system development of bioplatform plants and the formation of biofilm on it. The example of root development noted in the studies [28] is shown in Fig.6.

Maintenance of floating wetlands involves monitoring the hydrological regime of the reservoir, controlling the physico-chemical composition of water, monitoring the formation of bottom sediments and biofilm on plant roots, periodic inspection of the condition of phytomodules, replacing damaged elements, planting new plant species, and observing their vegetation. To prevent secondary water pollution, it is necessary to periodically remove excess plant biomass of CFW, including plant residues [50]. This procedure is also necessary to maintain the required oxygen level in the aquatic environment. The collected biomass is suitable for use as biofuel, biochar production, biofertilizers, and biosorbents [51]. In the USA, CFW technologies are actively being developed for growing ornamental plants on stormwater runoff. This allows not only to clean the water but also to generate high income from selling flowers and biomaterials for landscape design [52].

Fig.5. The state of phytocenoses created using different phytomodules: a – floating plant beds; b – bioplatform + grass turf; c – bioplatform + phytomats

Fig.6. Root system condition of plants on floating phytomodules: a – Scheuchzer’s cotton-grass; b – turf

The cost of CFW varies widely depending on the complexity of the design, configuration, materials used, coverage area, plant composition, maintenance level, and other parameters. According to [4], the cost range is from $5 to $12.5 per 1 m2. The highest price is noted for treatment facilities for stormwater and domestic wastewater with a total area of 400 m2, both self-made and industrially manufactured. The lowest cost is observed for combined treatment of municipal (60 %) and industrial wastewater (40 %) over an area of 4000 m2.

The cost of commercially produced CFW ranges from $38 (Beemats products) to $377 (BioHaven products) per 1 m2 [53]. Other studies estimate costs not per unit area of CFW but per 1000 m3 of treated water. M.Afzal et al. [25] report a treatment cost of $0.26 per 1000 m3 of wastewater in Pakistan. In China, the cost of municipal wastewater treatment at municipal treatment facilities is as follows: conventional treatment facilities $770 per 1000 m3; CW technology $22.3 per 1000 m3; CFW technology $0.26 per 1000 m3 [54]. In the Russian Federation, the cost of treating municipal wastewater at wastewater treatment plants in the Northwestern Federal District ranges from $7 to $270 per 1000 m3, depending on the depth of nitrogen removal (ITS-10-2015). These cost estimates clearly demonstrate the obvious advantages of using floating bioplatform technology, in addition to its important environmental protection significance.

Conclusion

We made a comprehensive review of the experience and prospects of applying the rapidly developing phytotechnology – Constructed Floating Wetlands. The paper describes the history of floating bioplatform creation and examines various design options. We present the results of water treatment from different sources using CFW and identify factors influencing the process efficiency. The study describes operational features of floating bioplatforms and approximate cost estimates for technology implementation in different countries.

The undeniable advantage of implementing floating bioplatforms in practice is the simplicity of manufacturing, placement, and maintenance of their phytomodules, which ensures high economic efficiency. The comparative analysis indicates the need for multifactorial experimental modelling during pilot experiments and mandatory verification of treatment efficiency under field conditions. The application of the technology at an enterprise should be based on the results of laboratory, scaled-up, and pilot-scale tests. After these tests are completed, a final decision on implementation is made.

The introduction of CFW technology holds great promise for treating various types of water for a wide range of pollutants, as well as for landscape design in different climatic conditions of the Russian Federation.

References

- Nefedeva E.E., Sivolobova N.O., Kravtsov M.V., Shaikhiev I.G. Wastewater post-treatment using phytoremediation. Vestnik tekhnologicheskogo universiteta. 2017. Vol. 20. N 10, p. 145-148.

- Kadlec R., Knight R., Vymazal J. et al. Constructed Wetlands for Pollution Control: Processes, Performance, Design and Operation. IWA Publishing, 2000, p. 159.

- Nivala J., van Afferden M., Hasselbach R. et al. The new German standard on constructed wetland systems for treatment of domestic and municipal wastewater. Water Science and Technology. 2018. Vol. 78. Iss. 11, p. 2414-2426. DOI: 10.2166/wst.2018.530

- Arslan M., Iqbal S., Islam E. et al. A protocol to establish low-cost floating treatment wetlands for large-scale wastewater reclamation. STAR Protocols. 2023. Vol. 4. Iss. 4, p. 102671. DOI: 10.1016/j.xpro.2023.102671

- Shuting Shen, Xiang Li, Xiwu Lu. Recent developments and applications of floating treatment wetlands for treating different source waters: a review. Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 2021. Vol. 28. Iss. 44, p. 62061-62084. DOI: 10.1007/s11356-021-16663-8

- Vymazal J., Yaqian Zhao, Mander Ü. Recent research challenges in constructed wetlands for wastewater treatment: A review. Ecological Engineering. 2021. Vol. 169. N 106318. DOI: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2021.106318

- Guanlong Yu, Guoliang Wang, Tianying Chi et al. Enhanced removal of heavy metals and metalloids by constructed wetlands: A review of approaches and mechanisms. Science of The Total Environment. 2022. Vol. 821. N 153516. DOI: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.153516

- Fuhao Zhang, Jie Wang, Liyuan Li et al. Technologies for performance intensification of floating treatment wetland – An explicit and comprehensive review. Chemosphere. 2024. Vol. 348. N 140727. DOI: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2023.140727

- Varma M., Gupta A.K., Ghosal P.S., Majumder A. A review on performance of constructed wetlands in tropical and cold climate: Insights of mechanism, role of influencing factors, and system modification in low temperature. Science of The Total Envi-ronment. 2021. Vol. 755. Part 2. N 142540. DOI: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142540

- Heikkinen K., Karppinen A., Karjalainen S.M. et al. Long-term purification efficiency and factors affecting performance in peatland-based treatment wetlands: An analysis of 28 peat extraction sites in Finland. Ecological Engineering. 2018. Vol. 117, p. 153-164. DOI: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2018.04.006

- Kumwimba M.N., Batool A., Xuyong Li. How to enhance the purification performance of traditional floating treatment wetlands (FTWs) at low temperatures: Strengthening strategies. Science of The Total Environment. 2021. Vol. 766. N 142608. DOI: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142608

- Korneykova M.V., Myazin V.A., Ivanova L.A. et al. Development and optimization of biological treatment of quarry waters from mineral nitrogen in the Subarctic, Geography, Environment, Sustainability. 2019. Vol. 12. N 2, p. 97-105. DOI: 10.24057/2071-9388-2019-5

- Suprun V.A., Ustinova V.V. Evaluation of the Technical and Economic Efficiency of Using the Developed Bioengineering Facility for Treatment and Decrease in the Mineralization of Drainage and Run-off Water. Ecology and Industry of Russia. 2023. Vol. 27. Iss. 8, p. 4-9 (in Russian). DOI: 10.18412/1816-0395-2023-8-4-9

- Rybka K.Yu., Shchegolkova N.M. The role of constructed wetlands in toxic metal wastewater treatment. Water: Chemistry and Ecology. 2018. N 1-3 (114), p. 101-112 (in Russian).

- Rybka K.Y., Shchegolkova N.M. Principles of constructed wetlands designing. RUDN Journal of Ecology and Life Safety. 2019. Vol. 27. N 4, p. 255-263 (in Russian). DOI: 10.22363/2313-2310-2019-27-4-255-263

- Pyka L.M., Al-Maruf A., Shamsuzzoha M. et al. Floating gardening in coastal Bangladesh: Evidence of sustainable farming for food security under climate change. Journal of Agriculture, Food and Environment (JAFE). 2020. Vol. 1. N 4, p. 161-168. DOI: 10.47440/JAFE.2020.1424

- Ghosh T.K., Singh A.K., Mitra S., Karmakar S. Gathering insights of the global scenario of floating-bed agriculture through systematic literature review for its promotion in Indian context. Progress in Disaster Science. 2024. Vol. 24. N 100367. DOI: 10.1016/j.pdisas.2024.100367

- Hoeger S. Schwimmkampen: Germany’s artificial floating islands. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation. 1988. Vol. 43. Iss. 4, p. 304-306. DOI: 10.1080/00224561.1988.12456222

- Zhongbing Chen, Cuervo D.P., Müller J.A. et al. Hydroponic root mats for wastewater treatment – a review. Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 2016. Vol. 23. Iss. 16, p. 15911-15928. DOI: 10.1007/s11356-016-6801-3

- Vymazal J. The Historical Development of Constructed Wetlands for Wastewater Treatment. Land. 2022. Vol. 11. Iss. 2. N 174. DOI: 10.3390/land11020174

- Ran Bi, Chongyu Zhou, Yongfeng Jia et al. Giving waterbodies the treatment they need: A critical review of the application of constructed floating wetlands. Journal of Environmental Management. 2019. Vol. 238, p. 484-498. DOI: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.02.064

- Hamad M.T.M.H. Comparative study on the performance of Typha latifolia and Cyperus Papyrus on the removal of heavy metals and enteric bacteria from wastewater by surface constructed wetlands. Chemosphere. 2020. Vol. 260. N 127551. DOI: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.127551

- Lucke T., Walker C., Beecham S. Experimental designs of field-based constructed floating wetland studies: A review. Science of The Total Environment. 2019. Vol. 660, p. 199-208. DOI: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.01.018

- Samal K., Kar S., Trivedi S. Ecological floating bed (EFB) for decontamination of polluted water bodies: Design, mechanism and performance. Journal of Environmental Management. 2019. Vol. 251. N 109550. DOI: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.109550

- Afzal M., Arslan M., Müller J.A. et al. Floating treatment wetlands as a suitable option for large-scale wastewater treatment. Nature Sustainability. 2019. Vol. 2. Iss. 9, p. 863-871. DOI: 10.1038/s41893-019-0350-y

- Evdokimova G.A., Ivanova L.A., Mjazin V.A. Patent N 2560631 RF. Device for biological purification of waste quarry waters. Publ. 20.08.2015. Bul. N 23 (in Russian).

- Ivanova L.A., Korneikova M.V., Myazin V.A., Fokina N.V., Redkina V.V., Evdokimova G.A. Patent N 189759 RF. Phy-tosystem module for biological treatment of industrial wastewater from mineral pollutants. Publ. 03.06.2019. Bul. N 16 (in Russian).

- Ivanova L.A., Myazin V.A., Korneikova M.V. et al. It's time to clean up the Arctic. Development of a phytotreatment system for post-treatment of nitrogen compounds from mining wastewater. Apatity: Izd-vo Kol'skogo nauchnogo tsentra, 2021, p. 88. DOI: 10.37614/978.5.91137.449.5

- Ivanova L.A., Kornejkova M.V., Myazin V.A., Fokina N.V., Redkina V.V., Evdokimova G.A. Patent N 2773122 RF. Module of a phytosystem for biological purification of industrial waste water from mineral contaminants. Publ. 30.05.2022. Bul. N 16 (in Russian).

- Chao Yang, Xiangling Zhang, Yuqi Tang et al. Selection and optimization of the substrate in constructed wetland: A review. Journal of Water Process Engineering. 2022. Vol. 49. N 103140. DOI: 10.1016/j.jwpe.2022.103140

- Pashkevich M.A., Korotaeva A.E., Matveeva V.A. Experimental simulation of a system of swamp biogeocenoses to improve the efficiency of quarry water treatment. Journal of Mining Institute. 2023. Vol. 263, p. 785-794.

- Fuchao Zheng, Tiange Zhang, Shenglai Yin et al. Comparison and interpretation of freshwater bacterial structure and interactions with organic to nutrient imbalances in restored wetlands. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2022. Vol. 13. N 946537. DOI: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.946537

- Lago A., Rocha V., Barros O. et al. Bacterial biofilm attachment to sustainable carriers as a clean-up strategy for wastewater treatment: A review. Journal of Water Process Engineering. 2024. Vol. 63. N 105368. DOI: 10.1016/j.jwpe.2024.105368

- Shengjiong Deng, Deshou Cun, Rufeng Lin et al. Enhanced remediation of real agricultural runoff in surface-flow constructed wetlands by coupling composite substrate-packed bio-balls, submerged plants and functional bacteria: Performance and mechanisms. Environmental Research. 2024. Vol. 263. Part 2. N 120124. DOI: 10.1016/j.envres.2024.120124

- Xuehong Zhang, Yue Lin, Hua Lin, Jun Yan. Constructed wetlands and hyperaccumulators for the removal of heavy metal and metalloids: A review. Journal of Hazardous Materials. 2024. Vol. 479. N 135643. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2024.135643

- Sharma R., Vymazal J., Malaviya P. Application of floating treatment wetlands for stormwater runoff: A critical review of the recent developments with emphasis on heavy metals and nutrient removal. Science of The Total Environment. 2021. Vol. 777. N 146044. DOI: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.146044

- Gupta V., Courtemanche J., Gunn J., Mykytczuk N. Shallow floating treatment wetland capable of sulfate reduction in acid mine drainage impacted waters in a northern climate. Journal of Environmental Management. 2020. Vol. 263. N 110351. DOI: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.110351

- Türker O.C., Vymazal J., Türe C. Constructed wetlands for boron removal: A review. Ecological Engineering. 2014. Vol. 64, p. 350-359. DOI: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2014.01.007

- Chuanqi Zhou, Jung-Chen Huang, Fang Liu et al. Selenium removal and biotransformation in a floating-leaved macrophyte system. Environmental Pollution. 2019. Vol. 245, p. 941-949. DOI: 10.1016/j.envpol.2018.11.096

- Stanley M., Palace V., Grosshans R., Levin D.B. Floating treatment wetlands for the bioremediation of oil spills: A review. Journal of Environmental Management. 2022. Vol. 317. N 115416. DOI: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.115416

- Rai P.K. Novel adsorbents in remediation of hazardous environmental pollutants: Progress, selectivity, and sustainability prospects. Cleaner Materials. 2022. Vol. 3. N 100054. DOI: 10.1016/j.clema.2022.100054

- Zhongbing Chen, Cuervo D.P., Müller J.A. et al. Hydroponic root mats for wastewater treatment – a review. Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 2016. Vol. 23. Iss. 16, p. 15911-15928. DOI: 10.1007/s11356-016-6801-3

- Baoshan Shi, Xiangju Cheng, Junheng Pan et al. Impact of water depth and flow velocity on organic matter removal and nitrogen cycling in floating constructed wetlands. Science of The Total Environment. 2024. Vol. 954. N 176731. DOI: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.176731

- Xiaohan Li, Xing Yan, Haojie Han et al. The trade-off effects of water flow velocity on denitrification rates in open channel waterways. Journal of Hydrology. 2024. Vol. 637. N 131374. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhydrol.2024.131374

- Stephenson R., Sheridan C. Review of experimental procedures and modelling techniques for flow behaviour and their re-lation to residence time in constructed wetlands. Journal of Water Process Engineering. 2021. Vol. 41. N 102044. DOI: 10.1016/j.jwpe.2021.102044

- Postila H., Ronkanen A.-K., Kløve B. Wintertime purification efficiency of constructed wetlands treating runoff from peat extraction in a cold climate. Ecological Engineering. 2015. Vol. 85, p. 13-25. DOI: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2015.09.066

- Kadlec R., Johnson K. Treatment wetlands of the far north. Ecological Engineering. 2023. Vol. 190. N 106923. DOI: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2023.106923

- Arslan M., Wilkinson S., Naeth M.A. et al. Performance of constructed floating wetlands in a cold climate waste stabilization pond. Science of The Total Environment. 2023. Vol. 880. N 163115. DOI: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.163115

- Chih-Yu Wang, Sample D.J., Day S.D., Grizzard T.J. Floating treatment wetland nutrient removal through vegetation harvest and observations from a field study. Ecological Engineering. 2015. Vol. 78, p. 15-26. DOI: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2014.05.018

- Rehman K., Imran A., Amin I., Afzal M. Inoculation with bacteria in floating treatment wetlands positively modulates the phytoremediation of oil field wastewater. Journal of Hazardous Materials. 2018. Vol. 349, p. 242-251. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2018.02.013

- Ladislas S., Gérente C., Chazarenc F. et al. Floating treatment wetlands for heavy metal removal in highway stormwater ponds. Ecological Engineering. 2015. Vol. 80, p. 85-91. DOI: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2014.09.115

- Locke-Rodriguez J., Troxler T., Sukop M.C. et al. Floating flowers: Screening cut-flower species for production and phytoremediation on floating treatment wetlands in South Florida. Environmental Advances. 2023. Vol. 13. N 100405. DOI: 10.1016/j.envadv.2023.100405

- Lynch J., Fox L.J., Owen Jr. J.S., Sample D.J. Evaluation of commercial floating treatment wetland technologies for nutrient remediation of stormwater. Ecological Engineering. 2015. Vol. 75, p. 61-69. DOI: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2014.11.001

- Dong Qing Zhang, Jinadasa K.B.S.N., Gersberg R.M. et al. Application of constructed wetlands for wastewater treatment in developing countries – A review of recent developments (2000-2013). Journal of Environmental Management. 2014. Vol. 141, p. 116-131. DOI: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2014.03.015