Experimental modeling of diamond dissolution in kimberlite within crustal cumulative centers

- 1 — Ph.D. Senior Researcher D.S.Кorzhinskii Institute of Experimental Mineralogy of RAS ▪ Orcid ▪ ResearcherID

- 2 — Ph.D., Dr.Sci. Chief Researcher D.S.Кorzhinskii Institute of Experimental Mineralogy of RAS ▪ Orcid ▪ ResearcherID

- 3 — Ph.D. Researcher Lomonosov Moscow State University ▪ Orcid ▪ Elibrary

Abstract

The main stages within the chemically active history of diamond genesis are proposed, from the upper-mantle chambers to the explosive ejections of diamonds and kimberlite material from cumulative centers to the surface. The paper focuses on the pre-final episode of diamond deposit genesis – the interaction of diamonds with carbonate-silicate kimberlite magmas in a crustal cumulate chamber. Such interactions are possible when the transport of diamonds by these magmas from the depths of the mantle primary chambers to the surface is stopped within crustal rock complexes with a strong roof. The cooling and solidification time of kimberlite melts in such cumulative centers is long enough to cause a significant mass loss of dissolving diamonds. The interaction of carbonate-silicate kimberlite melts with varying carbonate content with natural single-crystal diamonds was studied experimentally at a pressure of 0.15 GPa and a temperature of 1200 °C. Model carbonate, carbonate-fluid, natural kimberlite, and kimberlite-fluid systems were used as solvents. At experimental conditions, the solvents melted, and diamond crystals surface were underwent by dissolution. It was established that etching patterns are recorded on the growth planes, and diamonds lose mass: from 3-4.5 % after 2-hour exposure (the order of kimberlite transport time from the upper-mantle diamond-forming centers to the crustal cumulative centers) to 47.6 % after 10-day exposure (at the crustal cumulative center conditions). The results demonstrate that the dissolving ability of carbonate-silicate transport magmas is a factor that effectively reduces the diamond potential of kimberlite deposits.

Funding

The study is fulfilled under Research program N FMUF-2022-0001 of the IEM RAS.

Introduction

There are approximately 2500 known kimberlite pipes on the Earth, and only 25 of them are currently commercial diamond deposits. This means that less than 2-3 % of kimberlite pipes are of interest for industrial diamond mining [1]. This must be taken into account when formulating public policy on the effectiveness of mineral resource management [2]. One of the main risk factors in the formation of primary diamond deposits in kimberlite pipes is the dissolving capacity of carbonate and silicate-carbonate kimberlite melts for kinetically stable metastable diamonds [3-6]. Therefore, comprehensive mineralogical and experimental studies assessing the scale of diamond potential losses during diamond dissolution at various stages remain relevant today [7-10].

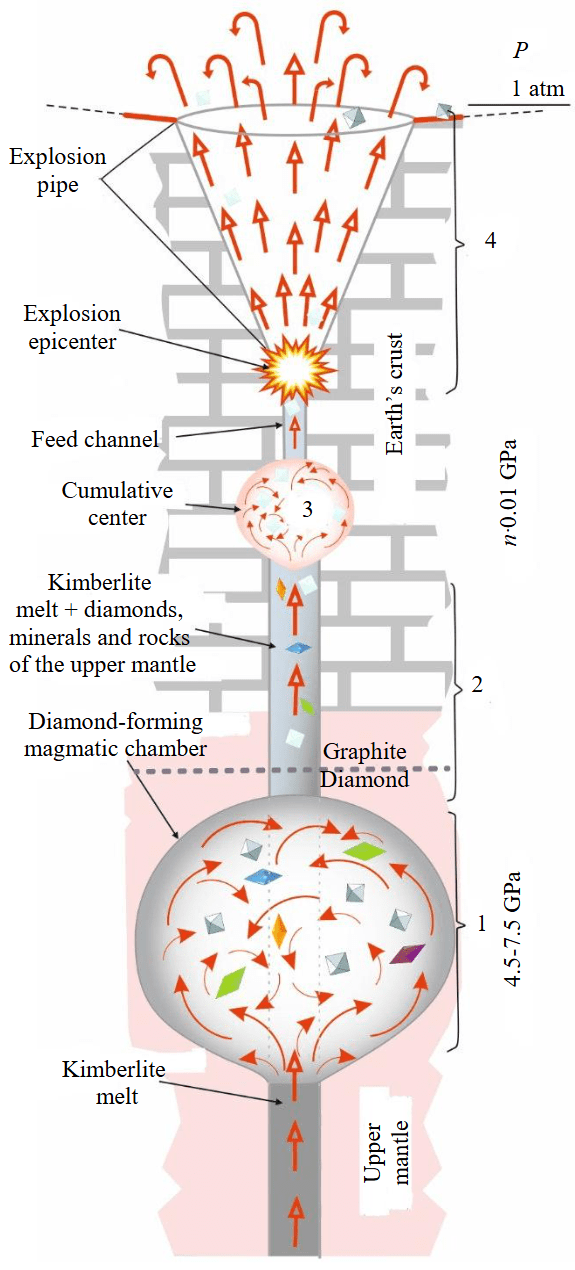

According to modern views, diamond is a polygenic mineral, forming in nature under various physicochemical and geodynamic conditions [1]. Based on a physicochemical approach combining experimental, mineralogical, and computational data, Yu.A.Litvin proposed the mantle-carbonatite theory for the formation of natural diamonds and associated paragenetic and xenogenic mineral phases [7, 11]. Later developed geological-genetic models for the formation of diamond deposits [12] are based on published information about diamond-bearing kimberlite systems and original studies of the ontogenetic features of diamond crystals, and are in agreement with the aforementioned mantle-carbonatite concept. Based on the proposed models, the main stages in the origin and evolution of kimberlite diamond deposits can be identified (Fig.1).

Fig.1. Schematic of diamond genesis and associated phases, and their evolution from route to the Earth’s surface

Stages in the origin and evolution of kimberlite diamond deposits

1. Primary diamond crystallization. Approximately 90 % of diamonds form in the subcratonic lithospheric mantle [1]. Their nucleation and growth (in a thermodynamically stable form) occur in stationary upper-mantle magma chambers of parental melts, where the maximum diamond potential of primary diamond deposits in the explosion kimberlite pipes is established. The formed diamonds can remain in the parental magma chamber for millions of years, unchanged or altered in shape due to subsequent growth stages, partial dissolution, or mass transfer [11, 13, 14].

2.Transport of diamonds by kimberlites from the mantle magma chamber to the Earth’s Below the upper-mantle magma chamber, the sublithospheric mantle begins to melt due to fluids [15]. Under a subcontinental thermal regime, metasomatized zones form where the temperature increases by several hundred degrees, thus kimberlite melts form. The surfaces of the formed diamonds begin to be actively affected by high-temperature carbonate-bearing kimberlite and assimilated diamond-forming melts, which are effective diamond solvents [7, 9, 14]. As they move towards the surface, kimberlite flows carry diamonds (with inclusions) along with genetically associated minerals and diamond-bearing rocks towards the Earth’s crust. The significantly carbonate (carbonatitic) composition of the liquid phase of kimberlite magma has been substantiated theoretically [3] and experimentally [16, 17].

Diamonds continue to partially lose mass in the transporting carbonate-bearing kimberlite melts during their ascent and emplacement to the continental crust. However, these losses are relatively small due to the short-term (up to several hours) dissolution of diamonds by magmas, with losses of up to 3.0-4.5 wt.% [7] during their transport into the Earth’s crust. On their way to the surface, the kimberlite magma carrying xenoliths can stop temporarily, when encountering dense rocks on its way and form episodic cumulative centers [18, 19]. During this process, the rate of diamond dissolution in kimberlites increases with decreasing pressure and increasing oxygen fugacity, at least from 6.3 to 1 GPa [20].

3. The final stopping of the kimberlite flow can ultimately occur within the Earth’s crust, in rock complexes with a strong roof, thus creating cumulative magma centers-chambers of kimberlite melts just before a kimberlite eruption. Here, at the lowest pressure of 0.15-0.20 GPa and still high temperatures of 1200-1250 °C [12, 21] the most favorable conditions for the dissolution of diamonds brought from the mantle depths are expected.

4. Formation of kimberlite explosion pipes. Most researchers agree on the explosive origin of diatremes as a result of the release of gases dissolved in the magma. At a depth of 1.5-3 km, regardless of temperature, the specific volume of dissolved water and CO2 sharply increases at pressures of 0.4-0.8 kbar, resulting in the formation of an explosion center and, consequently, an explosive ejection of the highly compressed contents of the cumulative center, forming an explosion cone and filling it with kimberlite and materials displaced from the upper mantle and Earth’s crust. As a result of the powerful explosion, kimberlite diamond deposits are created in the pipes, concentrating diamonds that survived after partial dissolution and were entrained by the explosion [6, 9]. At this final stage, we state the final diamond-bearing indicator of the deposit, but an additional damage to diamond content can be expected due to the incomplete removal of diamonds from the cumulative centers.

Therefore, one of the main risk factors at the formation of primary diamond deposits in kimberlite pipes is the dissolving ability of carbonate and silicate-carbonate kimberlite melts with respect to kinetically stable metastable diamonds. The extent of diamond loss due to dissolution can be determined experimentally.

The aim of this work was an experimental study of the interaction of carbonate-silicate melts with diamonds in crustal cumulative centers prior to kimberlite eruption, in order to assess the dissolving ability of carbonate and silicate-carbonate kimberlite melts, with application to the development of diamond crystal preservation factors and the determination of the productivity of primary diamond sources.

Experimental procedure

Experiments for investigation of the solubility of metastable but kinetically stable diamond were carried out on a high-pressure gas apparatus at P = 0.15 GPa and T = 1200 °C (IEM RAS, Chernogolovka). This temperature is consistent with the genetic geological model and geothermal studies [12, 21]. Solvent weight was 200 mg, along with a natural diamond crystal of various shapes (3-4 mm in size and weighing 30-50 mg), was placed in a Pt-capsule with a diameter of 7 mm, a height of 8 mm, and an ampoule wall thickness of 0.2 mm. The temperature was measured using a Pt70Rh30 (or Pt94Rh06) thermocouple and maintained by an automatic controller with an accuracy of ±2 °C. The duration of the experiments ranged from 2 to 12 days. Quenching cooling of the sample from 1200 to 800 °C occurred in 1.5-2.5 min. Reagents of analytical grade (99.5 %) were used as components for solvents of diamonds: CaCO3, Na2CO3, oxalic acid dihydrate H2C2O4·2H2O, and natural porphyritic kimberlite from the Nyurbinskaya pipe of the Yakutian diamond province (Kimb.Nyurb).

Model carbonate CaCO3, (CaCO3)50(Na2CO3)50, and carbonate-fluid (CaCO3)47.5(Na2CO3)47.5(H2C2O4·2H2O)5, wt.% compositions were used as solvents in the first stage of the experiments – to understand the complete picture of diamond dissolution in complex multicomponent kimberlitic systems, ranging from predominantly carbonate to silicate-carbonate compositions. The kimberlite-carbonate mixture (Kimb.Nyurb)80(CaCO3)20 served as the solvent at modeling the enrichment of kimberlite with Ca-carbonate just before an eruption (Table 1). To clarify the influence of the fluid on the diamond dissolution process another addition to the kimberlite was used – COH fluid in ratio 95:5 wt.%.

Analytical studies were performed at the IEM RAS. The experimental products were studied using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy on a Vega TS5130MM scanning electron microscope equipped with secondary and backscattered electron detectors and an INCA-PentaFET energy-dispersive X-ray detector for quantitative analysis. Microprobe analysis of the investigated samples were done at an accelerating voltage of 20 kV, an absorbed electron current of 0.1 nA, and a probe size of 0.1 µm. The analysis time per point (or area scan) was 70 s. The following were used as standards for quantitative analysis of the main elements: quartz, albite, MgO, Al2O3, wollastonite, as well as metals Mn, Cr, Ti, Fe.

Table 1

Starting chemical compositions of kimberlite-bearing media, wt.%

|

System |

SiO2 |

TiO2 |

Al2O3 |

Cr2O3 |

Fe2O3 |

MnO |

NiO |

MgO |

CaO |

Na2O |

K2O |

P2O5 |

CO2 |

H2O |

LOI* |

Sum |

|

Kimb.Nyurb |

31.47 |

0.52 |

4.03 |

0.11 |

8.53 |

0.08 |

0.15 |

30.30 |

8.09 |

0.06 |

0.83 |

0.54 |

15.21 |

99.92 |

||

|

(Kimb.Nyurb)80 (СaСO3)20 |

25.18 |

0.42 |

3.22 |

0.09 |

6.82 |

0.06 |

0.12 |

24.24 |

17.67 |

0.05 |

0.66 |

0.43 |

8.80 |

– |

12.17 |

99.94 |

|

(Kimb.Nyurb)95 H2C2O4·2H2O)5 |

29.90 |

0.49 |

3.83 |

0.10 |

8.10 |

0.08 |

0.14 |

28.79 |

7.69 |

0.06 |

0.79 |

0.51 |

2.50 |

2.5 |

14.45 |

99.92 |

|

*LOI – loss on ignition at 1100 °C for 1 day. |

||||||||||||||||

Raman scattering spectra of dissolved diamond crystals and the solvent medium after the experiments were obtained using a Renishaw RM1000 Raman spectrometer equipped with a Leica microscope (excitation wavelength 532 nm, power 20 mW). Spectra were recorded at 50x magnification for 100 s. The software used for data processing was Fytik 1.3.1 and OriginPro 2021. Phase identification of inclusions from Raman spectra was done using CrystalSleuth software and the RRUFF™ Project database [22]. After the experiments, the diamond crystals were cleaned with a sulfuric and nitric acid mixture, washed in alcohol, then in distilled water in an ultrasonic bath, and dried at a temperature of 120 °C. The loss of diamond mass was determined by precise weighing of the diamond crystals, with a measurement accuracy of 0.01 mg.

Experimental results on diamond dissolution at the conditions of crustal cumulative centers

Experiments on diamond dissolution at the conditions of crustal cumulative centers were conducted at a pressure of 0.15 GPa, a temperature of 1200 °C, and duration times ranging from 2 to 12 days. In the case of kimberlite and kimberlite-fluid systems samples after the experiments consisted of a dense mass with large and small pores (5-250 µm). The diamond crystal was separated with a little effort, leaving a smooth imprint in the quenching material. Carbonate and carbonate-fluid solvents after the experiments presented as a light, translucent, glassy, brittle mass. Sometimes, at opening the ampoule, spheres (50-200 µm) that appeared to be melted material could be found on its walls. The diamond crystal was easily extracted from the sample. Thus, the sample structures may indicate that the solvents were melted, and the diamond crystals were dissolved in the solvent melts.

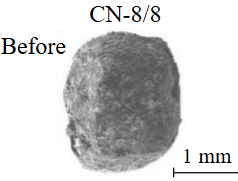

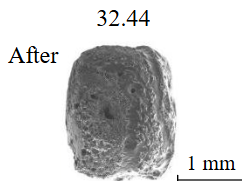

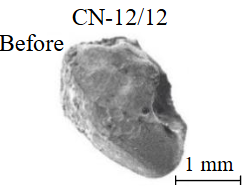

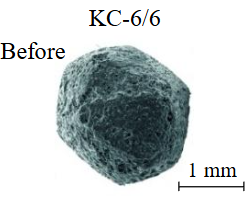

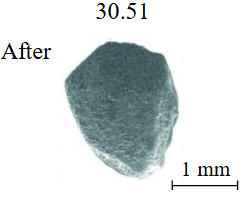

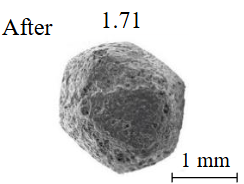

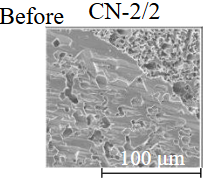

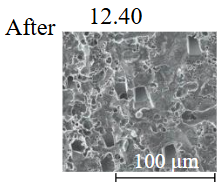

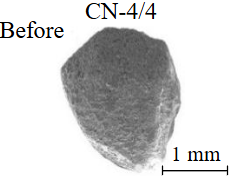

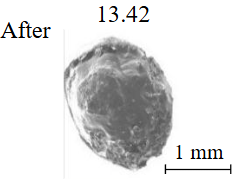

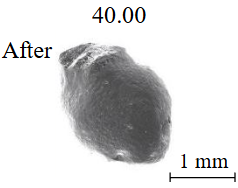

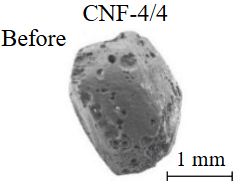

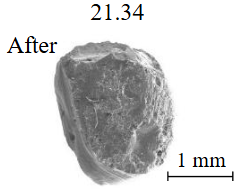

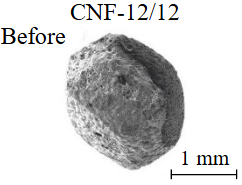

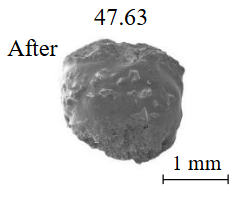

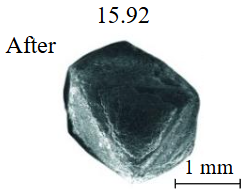

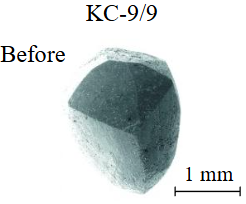

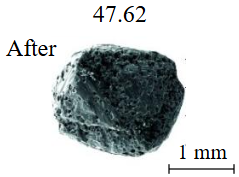

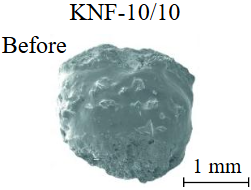

Diamond crystals undergoing dissolution in carbonate systems become more rounded, with their surfaces becoming smoother and more uniform than they were before the experiment (Table 2). Crystals from kimberlite systems exhibit increased roughness, porosity, and cavernousness due to the formation of numerous, varied indentations (Table 3). The photographs in Table 2 and 3 were acquired using backscattered electron mode. For natural diamonds, ditrigonal and shield-shaped layers on relict faces 111 are common relief features of planar-curved forms. The layered structure of the crystal (trigonal shield-like layers) is well observed in the experimental diamond crystal from experiment KC-6 (Table 3). During the layer-by-layer growth of diamond and incomplete formation (undergrowth) of a face to the edge, striations appear along the crystal edges, formed by the ends of octahedral faces – so-called parallel striations (run КС-12). Dissolution of the edges of octahedral faces produces sheaf-like (ditrigonal) striations. This texture can be observed on the faces of diamond crystals from the CNF-4 and KC-12 experiments (Table 2, 3).

Table 2

Experimental conditions for diamond dissolution in carbonate systems, diamond mass loss, and SEM images of diamond crystals before and after dissolution

|

Solvent |

Sample number/duration, days |

Mass loss, % |

Sample number/duration, days |

Mass loss, % |

|

CaCO3 |

|

|

||

|

(CaCO3)50(Na2CO3)50 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

[(CaCO3)50(Na2CO3)50]95 (COH)5 |

|

|

|

|

Table 3

Experimental conditions for diamond dissolution in kimberlite systems, diamond mass loss, and SEM images of diamond crystals before and after dissolution

|

Solvent |

Sample number/duration, days |

Mass loss, % |

Sample number/duration, days |

Mass loss, % |

|

(Kimb.Nyurb)80 (CaCO3)20 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

(Kimb.Nyurb)95 (COH)5 |

|

|

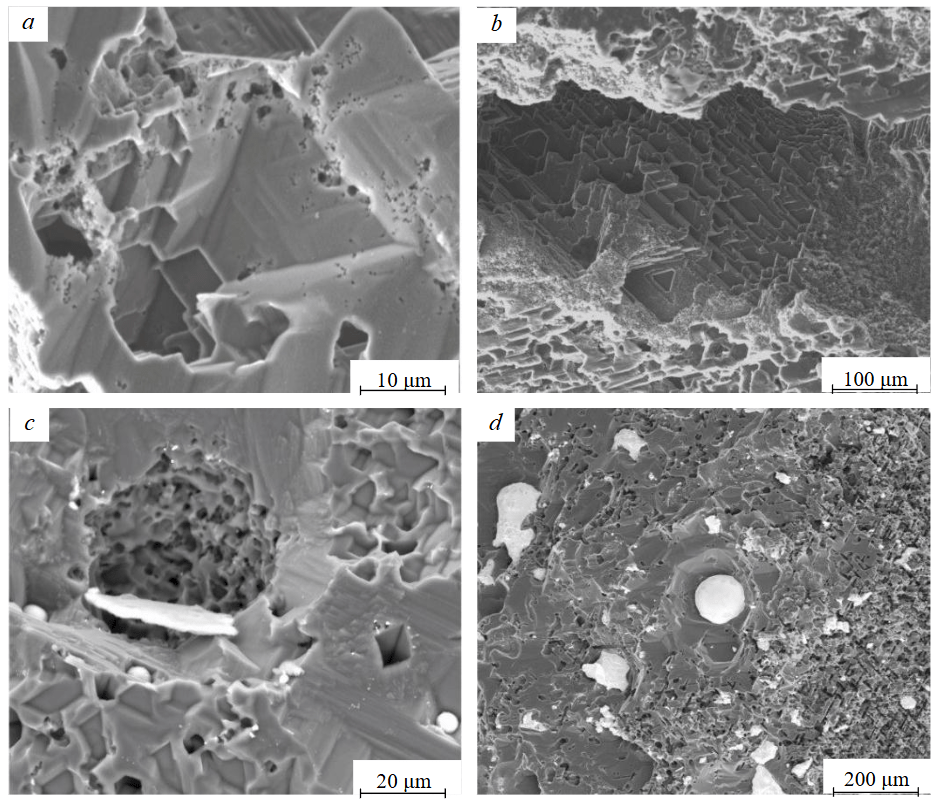

Another widely occured relief element on the 111 faces of natural diamonds are “negative trigons” [23]. Negative triangular features are evident on nearly all crystals after the experiments (Table 2, 3). Figure 2, а, b displays the magnified surface of etched facets, revealing clear negative trigons. Distinct spheres, presumably of quenched melt, are readily observed within the etch pyramids on the diamond surface (Fig.2, c, d). In the same images, it is evident that certain large triangular pits with truncated vertices have evolved into hexagonal forms.

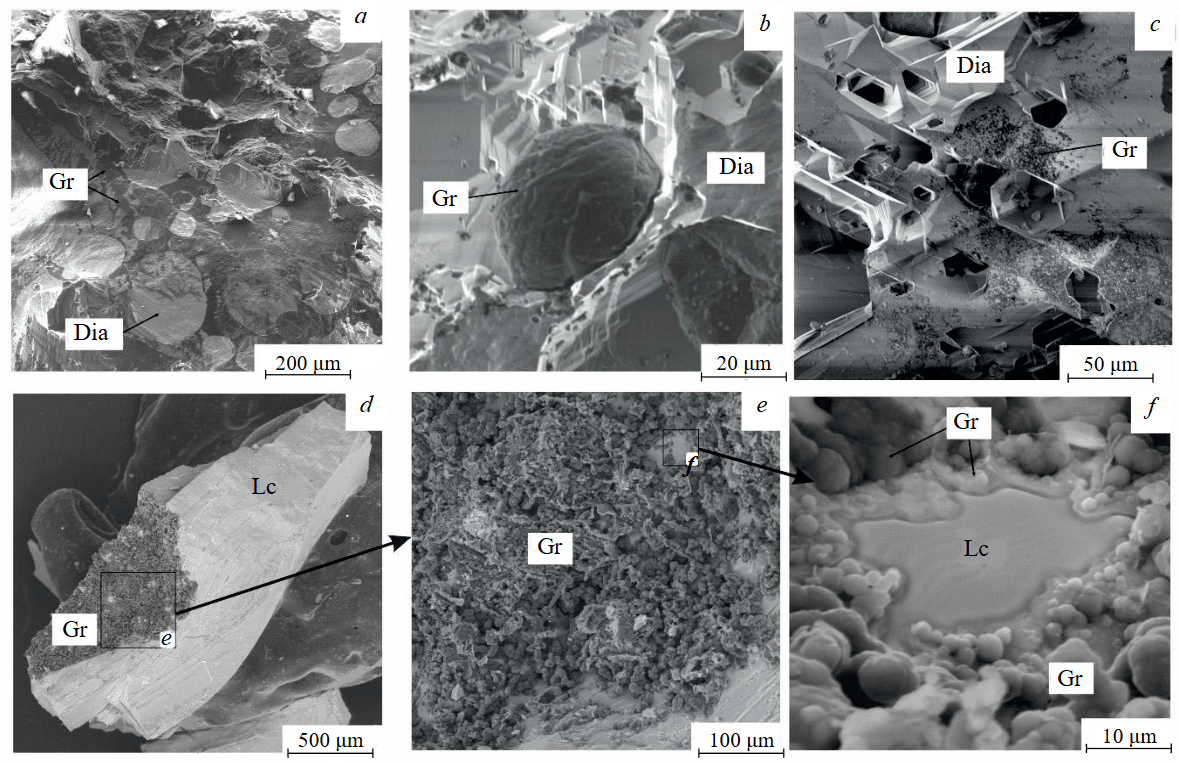

Fig.2. SEM images of etched diamond surfaces at backscattered electron mode: a – from experiment KC-9; b – from experiment CN-8; at mixed backscattered and secondary electron mode: c – from experiment CN-4; d – CNF-12

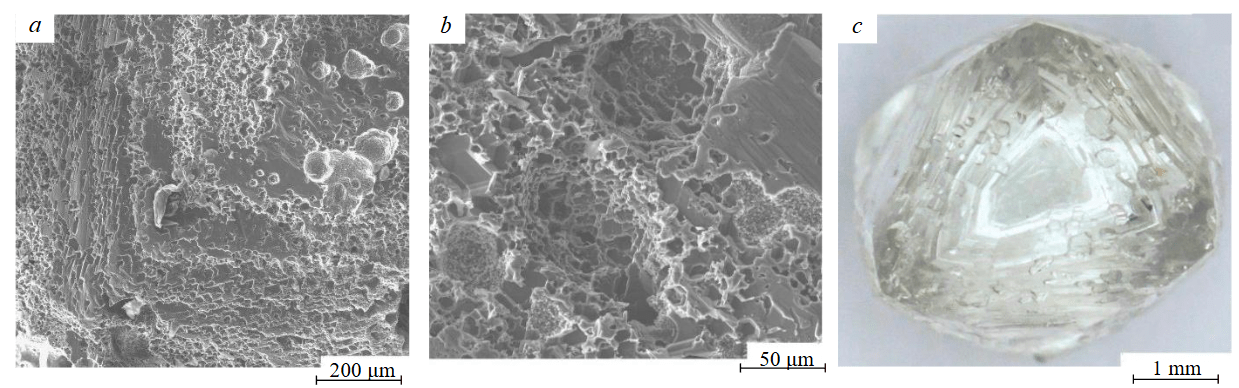

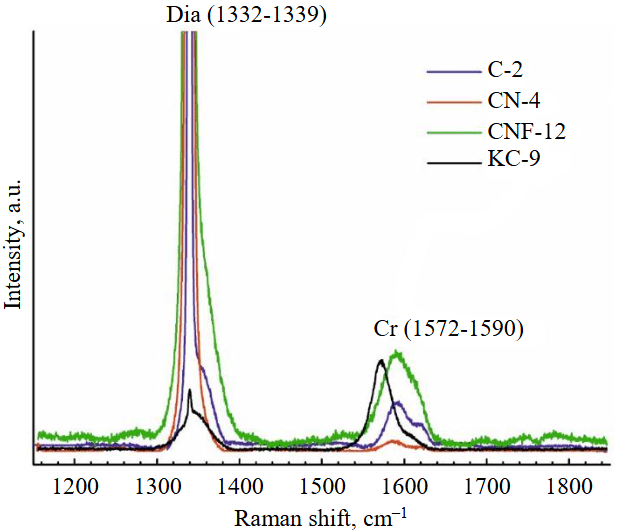

There is a diamond crystal with a finely pitted etched surface after acid cleaning of solidified melt-solvent particles on the Fig.3, а, b. Raman spectroscopy of partially dissolved crystals demonstrated the presence of both diamond and graphite peaks (Fig.4), signifying surface graphitization of the diamonds. At using all types of solvents, the diamonds after experiments were covered with a graphite film of varying thickness. Rounded imprints of melt/fluid bubbles were observed on this film (Fig.5, а). Graphite formed spherical inclusions in carbonate and carbonate-fluid systems (Fig.5, b). Figure 5, d-f demonstrates the process of “crust” formation at the interface between diamond and the carbonate medium. The “crust” consists of chains of graphite microspheres. The formation of graphite “dust” on the dissolving diamond crystal (Fig.5, c) was observed in runs with kimberlite solvent (KC-6, KC-12). Furthermore, Raman spectra of diamonds from these experiments often showed graphite peaks, despite the fact that visual inspection under an optical microscope revealed crystals that appeared “conditionally clean” without a graphite film.

Fig.3. Micro-pitted etching morphology: а – on the surface of a diamond crystal from experiment CN-4; b – in a natural diamond crystal from the Zapolyarnaya kimberlite pipe (Yakutia, Russia); c – natural corrosion of a natural crystal (b).

Photos were taken using an optical microscope at backscattered electron mode

Fig.4. Raman spectra of dissolved diamonds after experiments, prior to acid purification

Fig.5. Graphite formation:а – diamond surface in a graphite film after experiment CN-4; b – graphite sphere on the diamond surface after experiment CNF-4; c – graphite “dust” on the diamond surface from experiment KC-6; d-f – graphite “crust” on the surface of a quenched carbonate melt at the interface with the dissolving diamond from experiment CNF-4. SEM photos of the samples at secondary electron mode (а-c), at mixed mode of reflected and secondary electrons (d-f)

Dia – diamond; Gr – graphite; Lc – carbonate melt

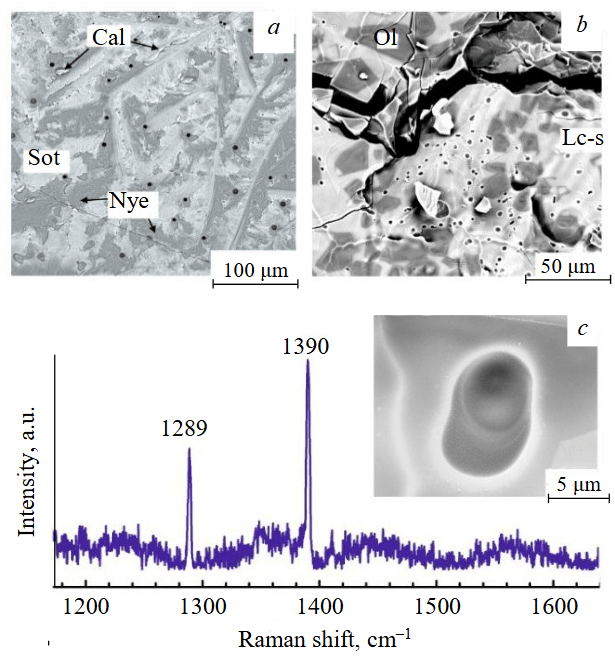

The carbonate melt after the experimental procedures was a dense, white, glass-like substance. Its composition consisted of quenched dendritic crystals of calcium carbonates (in case of CaCO3-solvent) or calcium and sodium carbonates (in case of a carbonate mixture (CaCO3)50(Na2CO3)50) – niererite Na2Ca(CO3)2, shortite Na2Ca2(CO3)3, and calcite CaCO3, as confirmed by micro-X-ray spectral analysis and Raman spectroscopy (Fig.6, a). The sizes of the quenched crystals vary over a wide range from 1 to 100 μm. Numerous micro-voids are observed in the quenched mass, which are most likely related to the release of gaseous H2O during quenching, this water originates from the atmosphere and is bound by hygroscopic sodium carbonate at the start of the experiment.

Fig.6. Formation of micro-voids in samples after experiments due to the release of gaseous H2O and/or CO2: a – run CN-8; b – run KNF-10; c – СO2-gas bubble in the experiment in quenched kimberlite melt and its Raman spectrum. SEM photos at secondary electrons mode

Ol – olivine; Cal – calcite; Nye – nyererite; Sot – shortite; Lc-s – carbonate-silicate melt

Experiments involving the carbonate-fluid system (CaCO3)47.5(Na2CO3)47.5(COH)5 did not reveal any substantial calcium phases. Areas with round micro-voids are found in the samples, where gas, H2O and/or CO2 contained in the starting composition was released during quenching. The size of the quenched crystallites is in the range of one to tens of micrometers.

During the experiments, the solvents in the experimental (Kimb.Nyurb)80(CaCO3)20 system samples were predominantly heterogeneous, consisting of: melt ± solid phase (including olivine, clinopyroxene, and calcite) ± fluid (CO2 and H2O). In all experiments, after quenching, the majority of the kimberlite solvent consists of isometric, spherical quench formations, 5-25 µm in cross-section, that are in conformal contact with one another, similar to pillow lavas. The quenched melt within these “pillows” occupies 75-80 % of the sample. It is homogeneous (though fine-grained areas are also encountered), with a Ca-carbonate-silicate composition and a calculated CO2 content of 15-22 wt.%. Relief phase relationships are evident on unpolished sample breaks. Large pores and channels indicate fluid presence in the melt during the experiment and its release during quenching. Furthermore, bubble imprints made of Ca-carbonate-silicate glasses are commonly found in the bulk of the samples.

The experimental sample of the system (Kimb.Nyurb)95(COH)5 also showed the formation of a homogeneous miscible carbonate-silicate substance, likely a melt (Fig.6, b) and silicate minerals, including olivine 20-100 µm and clinopyroxene up to 400 µm. It should be noted that the KNF-10 experiment, representing a kimberlite-fluid system, was the only successful experiment in the series. In the other experiments with this start composition, the hermetically sealed ampoules could not withstand prolonged exposition and were exploded due to the large amount of free fluid. This is evidenced by the abundance of pores (bubbles) in the quenched mass. According to Raman spectroscopy data, gaseous CO2 was detected in a closed bubble (Fig.6, c).

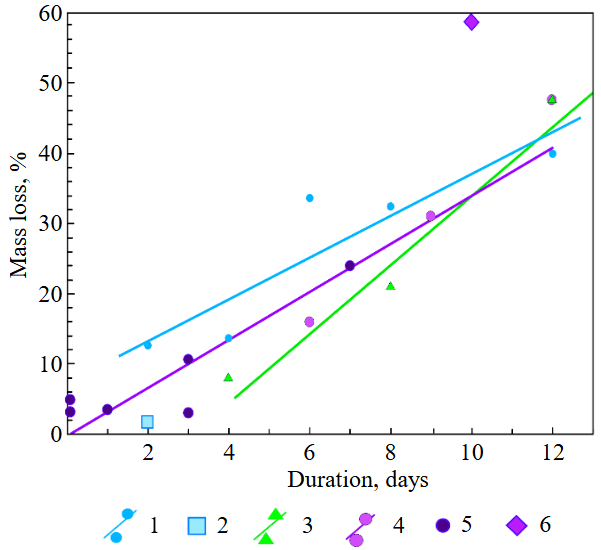

The experimental conditions and diamond mass loss are presented in Table 2, 3 and summarized in the graph (Fig.7). The lowest diamond mass loss (1.7 %) was recorded in Ca-carbonate melts after a 2-day duration. In the case of using a Ca,Na-carbonate solvent, diamond mass loss ranges from 12.40 to 39.97 % over duration periods of 2 to 12 days. Furthermore, the diamond mass loss for duration of 10 and 12 days is practically identical. The addition of 5 % fluid to the carbonate system, its influence is only evident after 12 days duration. In this carbonate-fluid melt, the mass loss reaches 47.63 %, representing an increase of 7.66 % over the mass loss observed in the “dry” carbonate melt. In experiments with kimberlite as a solvent, diamond mass loss ranged from 15.92 % after 6 days of duration to 47.62 % after 12 days of duration. Maximum losses of up to 58.79 % after 10 days of duration were recorded in the kimberlite-fluid solvent. It should be noted that after 12-day duration, the mass losses of diamonds demonstrate a very similar value for carbonate, carbonate-fluid, and kimberlite solvents.

Fig.7. Dependence of diamond mass loss at their dissolution in carbonate, carbonate-fluid, kimberlite, and kimberlite-fluid solvents on duration time at Р = 0.15 GPа, Т = 1200-1250 °С

1 – (CaCO3)50(Na2CO3)50; 2 – CaCO3; 3 – (CaCO3)47.5(Na2CO3)47.5(COH)5; 4 – kimberlite of Nyurbinskaya pipe; 5 – kimberlite of Nyurbinskaya pipe by [7]; 6 – (Kimb.Nyurb)95(СОН)5

Discussion

The results of this experimental study on diamond dissolution in carbonate and kimberlite melts in the presence of a fluid or in dry systems demonstrate that at crustal conditions, specifically within a crustal cumulative center of kimberlite melt (P = 0.15 GPa and T = 1200 °C with varying carbonate content), significant dissolution of transported diamond crystals is possible, up to 47.6 % after 10 days of duration.

Studies have demonstrated that in the crustal cumulative center, kimberlitic, kimberlite-fluid, carbonate, and kimberlite-carbonate mixtures melt, forming a melt that is the principal driver of diamond dissolution in the cumulative chamber. Solvent melting can be diagnosed by several indicators, both structural and analytical. The formation of carbonate spheres in dissolution pits on the diamond surface, the rounded pores within the dense but brittle carbonate material, and the diamond's own mass loss all suggest that these processes could only have taken place in a melt.

According to estimates based on experimental data, the primary melting temperature at the solidus of multicomponent kimberlites occurs between 800-1100 °C at pressures ranging from 0.1-0.2 GPa. The high porosity characterized by rounded pores and channels, the homogeneous chemical composition of the cement matrix between the rounded olivine grains, and the microstructures observed in the quenched samples all support the interpretation of melting. The kimberlite-carbonate mixture also melted, forming homogeneous carbonate-silicate melts and, upon quenching, these melts resulted in glasses with pores and impressions of released gas bubbles, in contrast to the alkali-carbonate-silicate immiscibility at 0.2 GPa and 1100-1250 °C [24].

The dissolution of diamonds in molten solvents led to morphological alterations, characterized by the formation of distinct dissolution morphologies. The fine pitting observed during the etching of diamond crystals in the experiment is analogous to the “corrosion” known in natural samples (see Fig.3, c). This phenomenon can be observed as scattered pits on the crystal’s surface, as well as a fine, net-like pattern across a surface area. Parallel hatching (as seen in experiment KC-12) can be revealed through the dissolution of diamond in metal-sulfide ± silicate solvents at 4.0-4.5 GPa and 1400-1450 °C [25, 26]. Rounded crystals are prevalent in natural diamonds [27], with the majority of their formation due to the interaction with kimberlite melt [28-30]. The conditions and mechanisms of this interaction have been the subject of long-standing scientific debate. Predominantly, they are characterized by a wide range of surface sculptures, such as trigonal or hexagonal pits, ditrigonal and shield-like layers, droplet-shaped tubercles, striations of varying intensity, and many other sculptural elements. Experimental investigations have revealed that surface sculptures on natural diamonds can be indicative of both dissolution conditions and the internal features of diamond crystals [31].

The results of experimental studies on the dissolution of diamond crystals (octahedral, pseudorhombo-dodecahedral ones, and cubes) in water-bearing carbonate and silicate melts at temperatures of 1100-1450 °C and pressures of 1-5.7 GPa [14] demonstrated that crystal dissolution can occur both during the ascent of diamonds from the mantle (upon contact with kimberlite and lamproite melts), as well as while diamonds are within the mantle. The authors demonstrated that the surface sculptural features observed on the experimental crystals are similar to those found on naturally dissolved crystals. In experiments, at a dissolution degree of 25 %, the octahedral faces are completely replaced by rounded surfaces. With further dissolution, the curvature of the surfaces changes, and at a weight loss of 45-50 %, the dissolution form of a pseudorhombo-dodecahedron becomes close to the dissolution form of an octahedron. At 50 % weight loss, cubic faces become tetrahexahedroidal and rounded, showing many quadrangular etch pits. Intensive dissolution creates deep etch channels at block boundaries, leading to a high chance of breaking along these channel’s line.

The research group experimentally found that the rate at which diamonds dissolve in kimberlitic magmas increases as pressure decreases from 6.3 to 1.0 GPa [8]. Therefore, the maximum diamond dissolution rate can be expected at the level of the Earth's crust. Previously, the interaction of Nyurbinskaya pipe kimberlite melts (Yakutia) with natural single-crystal diamonds was experimentally investigated at 0.15 GPa and 1200-1250 °C for 2 h (estimated time scale for kimberlite transport from upper-mantle diamond-forming sources to crustal cumulative centers) [7]. With weak surface dissolution of diamonds in Ca-carbonate-bearing kimberlite melt, diamond mass loss ranges from 3.0 to 4.5 %. This indicates that diamond dissolution occurs during transport, but it is insignificant due to the high ascent rate and, consequently, short residence time. The dissolution of a diamond crystal at all stages of its genesis and in the cumulative center, in particular, is discussed with reference to natural diamond “Matryoshka” [32].

Some models of kimberlite ascent suggest the upward movement of a localized, vertically constrained fracture filled with volatile-rich magma through the lithospheric mantle [12, 33]. Typical ascent rates for kimberlite magma are estimated to be between 10-30 m/s. Decarbonation and gas release are ongoing processes during the kimberlite magma's journey to the surface. As the melts rise, reactions between solid or liquid carbonates and silicates occur, leading to the release of CO2. Furthermore, a decrease in the viscosity of the kimberlite melt by more than 3 times by the time it reaches the surface can also contribute to its rapid ascent [34].

According to E.A.Vasiliev [19], the dominance of a single diamond population in a kimberlite pipe (characterized by exceptional preservation and crystal quality, relative simplicity of their anatomy, uniformity of spectroscopic characteristics, and minimal dissolution of crystals, as observed, for example, in the Mir and Internatsionalnaya pipes) may indicate that, after the activation of kimberlite formation, a portion of the melt containing diamonds grown in a single crystallization cycle rapidly ascended to the surface, forming the kimberlite bodies. In more complex cases E.A.Vasiliev suggests the possibility of stopping that non-opening crack that drives the kimberlite melt containing diamonds at rheological boundaries, leading to the formation of an intermediate chamber where the melt cools and solidifies. In this process, some crystals are deformed and dissolved, while aggregation of defects in the crystalline structure occurs, forming complex shapes. The Zapolyarnaya diamond pipe and the M.V.Lomonosov deposit are examples of such objects, among others.

Experimental samples exhibited diamond graphitization. Diamond is known to be the thermodynamically stable phase at high pressures, while graphite is relatively stable at low pressures, down to ambient [7]. The boundary between the stability fields of diamond and graphite is defined by the graphite-diamond equilibrium curve. Graphite is kinetically stable and metastable in the diamond stability field, and diamond is kinetically stable and metastable in the graphite stability field. On the graphite-diamond equilibrium curve, the equilibrium solubilities of graphite and diamond in any solvent composition are equal. In the graphite stability region, the equilibrium solubility of diamond is greater than the solubility of the stable graphite phase. However, in a strictly isothermal experiment, the concentration of dissolved carbon in metastable diamond approaches, but cannot reach, its solubility value [35]. When the solution that dissolves metastable diamond (which has higher solubility) becomes oversaturated with respect to stable graphite (which has lower solubility), graphite crystallization happens automatically. The process can proceed until metastable diamond is completely dissolved, with continuous crystallization of stable graphite. This is the reason for the difficulties in experimentally measuring the “equilibrium” solubility of metastable diamond. This is also evidenced by the findings of graphite, and graphite films on diamond crystals of impact and metamorphic diamonds [36, 37]. Surface graphitization on diamonds from kimberlites and xenoliths occurs less frequently, in the form of very thin, semi-transparent to dense opaque graphite films [38]. Surface graphitization of diamond has been experimentally documented in undersaturated volatile silicate melts, including basaltic and kimberlitic compositions, even at high pressures [23, 39, 40].

Kimberlite pipe formation demands a huge quantity of gas, driving the melt to boil and mix with the pipe’s molten and solidified magmatic rocks [41]. Gases may start forming and accumulating in kimberlite magma right from the initial stage of the deep kimberlite melt's ascent from the mantle diamond-forming source. In addition to the original gas source, incongruent melting of carbonates occurs at various depths: magnesite MgCO3 below 2.3 GPa [42], dolomite CaMg(CO3)2 at 0.5 GPa, siderite FeCO3 between 0.05 and 1 GPa [43], calcite CaCO3 at 0.1-0.7 GPa [44]. Moreover, the Earth's crust, where the cumulative centers form, contains carbonates and hydrous minerals, may be capable of supplying CO2 and H2O.

Crystallization of the liquidus silicate phases of olivine and clinopyroxene from kimberlitic magma increases the proportion of the carbonate component in residual kimberlitic melts. According to experimental data and thermodynamic modeling, the solubility of CO2 in these melts decreases with decreasing temperature [10], which causes the separation of dissolved carbon dioxide in the form of a free fluid. As the kimberlitic system solidified upon quenching, the internal fluid pressure within the bubbles increased and grew, leading to the rupture of their envelopes. Internal fluid pressure increased when the kimberlite system solidified during quenching in bubbles, resulting in the disintegration of their shells. At low pressures, the solubility of the fluid in the kimberlite melt decreases, leading to their increasing separation from the melt. These gases, along with those produced by decomposition, accumulate in large volumes prior to eruption. The mechanism for accumulating free gases, particularly CO2, could have also occurred within crustal cumulative kimberlite centers as they cooled. In the experiment, the presence of gas in this study is indicated by a large number of pores in the quenched samples (see Fig.6, a, b). Raman spectroscopy has detected gaseous CO2 in these enclosed bubbles. Moreover, the accumulation of gases and the large volumes of the cumulative centers allow the kimberlite melt to mix actively, enhancing diamond dissolution.

In this way, if a kimberlite flow encounters an obstruction in form of a dense crust rocks, it will likely be stopped there for some time (day or more), resulting in the formation of a stationary crustal cumulative center. At these conditions, experimentally modelling in this work, significant dissolution of diamonds in kimberlitic fluidized melts is most probable and can reach up to ~45-50 % with a lifetime of such a center about 10 days.

Conclusion

Our experiments investigating diamond dissolution in carbonate and kimberlite melts, under both fluid-present and dry conditions, reveal that Ca,Na-carbonate melts display the highest solubility for hold times up to 6 days, when compared to kimberlite and carbonate-fluid (5 wt.% fluid) melts. For longer exposure times (up to 12 days), the aggressiveness of the experimental media and the solubility of diamond in them are practically the same under the conditions of a crustal cumulative chamber (0.15 GPa and 1200 °C). This allows for substantial dissolution of introduced diamond crystals, reaching up to 47.6 % after 10 days.

The role of crustal cumulative centers as the main risk factors for the reduction of diamondiferous potential in deposits is shown. If there are “stopping points” along the diamond’s path to the Earth’s surface, the final stop occurs in the crustal rocks just before the kimberlite eruption. The crystals brought into the chambers dissolve considerably within them, up to complete disappearance, depending on the lifetime of that cumulative center. The degree of dissolution of the deposit’s main crystal generation allows for an estimation of the probability of kimberlite magma containing diamonds being delayed in cumulative centers.

References

- Kaminsky F.V., Voropaev S.A. Modern Concepts on Diamond Genesis. Geochemistry International. 2021. Vol. 59. N 11, p. 1038-1051. DOI: 10.1134/S0016702921110033

- Litvinenko V.S., Petrov E.I., Vasilevskaya D.V. et al. Assessment of the role of the state in the management of mineral resources. Journal of Mining Institute. 2023. Vol. 259, p. 95-111. DOI: 10.31897/PMI.2022.100

- Golovin A.V., Kamenetsky V.S. Compositions of Kimberlite Melts: A Review of Melt Inclusions in Kimberlite Minerals. Petrology. 2023. Vol. 31. N 2, p. 143-178. DOI: 10.1134/S0869591123020030

- Sokol A.G., Kruk A.N., Persikov E.S. Dissolution of Peridotite in a Volatile-Rich Carbonate Melt as a Mechanism of the Formation of Kimberlite-like Melts (Experimental Constraints). Doklady Earth Sciences. 2022. Vol. 503. Part 2, p. 157-163. DOI: 10.1134/S1028334X22040183

- Litvin Yu.A., Spivak A.V., Kuzyura A.V. Physicogeochemical Evolution of Melts of Superplumes Uplift from the Lower Mantle to the Transition Zone: Experiment at 26 and 20 GPa. Geochemistry International. 2021. Vol. 59. N 7, p. 661-682. DOI: 10.1134/S0016702921070041

- Giuliani A., Schmidt M.W., Torsvik T.H., Fedortchouk Y. Genesis and evolution of kimberlites. Nature Reviews Earth & Environment. 2023. Vol. 4. Iss. 11, p. 738-753. DOI: 10.1038/s43017-023-00481-2

- Litvin Yu.A., Kuzyura A.V., Varlamov D.A. et al. Interaction of Kimberlite Magma with Diamonds Upon Uplift from the Upper Mantle to the Earth’s Crust. Geochemistry International. 2018. Vol. 56. N 9, p. 881-900. DOI: 10.1134/S0016702918090070

- Khokhryakov A.F., Kruk A.N., Sokol A.G., Nechaev D.V. Experimental Modeling of Diamond Resorption during Mantle Metasomatism. Minerals. 2022. Vol. 12. Iss. 4. N 414. DOI: 10.3390/min12040414

- Smit K.V., Shirey S.B. Diamonds Are Not Forever! Diamond Dissolution. Gems & Gemology. 2020. Vol. 56. N 1, p. 148-155.

- Fedortchouk Y., Liebske C., McCammon C. Diamond destruction and growth during mantle metasomatism: An experimental study of diamond resorption features. Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 2019. Vol. 506, p. 493-506. DOI: 10.1016/j.epsl.2018.11.025

- Litvin Y.A. Genesis of Diamonds and Associated Phases. Springer, 2017, p. 51. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-54543-1

- Kozlov A.V., Vasilev E.A., Ivanov A.S. et al. Genetic geological model of diamond-bearing fluid magmatic system. Journal of Mining Institute. 2024. Vol. 269, p. 708-720.

- Gubanov N.V., Zedgenizov D.A., Vasilev E.A., Naumov V.A. New data on the composition of growth medium of fibrous diamonds from the placers of the Western Urals. Journal of Mining Institute. 2023. Vol. 263, p. 645-656.

- Khokhryakov A.F., Palyanov Y.N. The evolution of diamond morphology in the process of dissolution: Experimental data. American Mineralogist. 2007. Vol. 92. Iss. 5-6, p. 909-917. DOI: 10.2138/am.2007.2342

- Dasgupta R., Chowdhury P., Eguchi J. et al. Volatile-bearing Partial Melts in the Lithospheric and Sub-Lithospheric Mantle on Earth and Other Rocky Planets. Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry. 2022. Vol. 87, p. 575-606. DOI: 10.2138/rmg.2022.87.12

- Sharygin I.S., Litasov K.D., Shatskiy A. et al. Experimental constraints on orthopyroxene dissolution in alkali-carbonate melts in the lithospheric mantle: Implications for kimberlite melt composition and magma ascent. Chemical Geology. 2017. Vol. 455, p. 44-56. DOI: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2016.09.030

- Shatskiy A., Litasov K.D., Sharygin I.S., Ohtani E. Composition of primary kimberlite melt in a garnet lherzolite mantle source: constraints from melting phase relations in anhydrous Udachnaya-East kimberlite with variable CO2 content at 6.5 GPa. Gondwana Research. 2017. Vol. 45, p. 208-227. DOI: 10.1016/j.gr.2017.02.009

- Simakov S.K., Stegnitskiy Yu.B. On the presence of the postmagmatic stage of diamond formation in kimberlites. Journal of Mining Institute. 2022. Vol. 255, p. 319-326. DOI: 10.31897/PMI.2022.22

- Vasilev E.A. Defects of diamond crystal structure as an indicator of crystallogenesis. Journal of Mining Institute. 2021. Vol. 250, p. 481-491. DOI: 10.31897/PMI.2021.4.1

- Khokhryakov A.F., Kruk A.N., Sokol A.G. The effect of oxygen fugacity on diamond resorption in ascending kimberlite melt. Lithos. 2021. Vol. 394-395. N 106166. DOI: 10.1016/j.lithos.2021.106166

- Kavanagh J.L., Sparks R.S.J. Temperature changes in ascending kimberlite magma. Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 2009. Vol. 286. Iss. 3-4, p. 404-413. DOI: 10.1016/j.epsl.2009.07.011

- Lafuente B., Downs R.T., Yang H., Stone N. 1. The power of databases: The RRUFF project. Highlights in Mineralogical Crystallography. De Gruyter, 2016. P. 1-30. DOI: 10.1515/9783110417104-003

- Fedortchouk Y., Zhuoyuan Li, Chinn I., Fulop A. Geometry of dissolution trigons on diamonds: Implications for the composition of fluid and kimberlite magma emplacement. Lithos. 2024. Vol. 470-471. N 107526. DOI: 10.1016/j.lithos.2024.107526

- Shapovalov Yu.B., Kotelnikov A.R., Suk N.I. et al. Liquid Immiscibility and Problems of Ore Genesis: Experimental Data. Petrology. 2019. Vol. 27. N 5, p. 534-551. DOI: 10.1134/S0869591119050060

- Chepurov A.I., Sonin V.M., Zhimulev E.I. et al. Dissolution of diamond crystals in a heterogeneous (metal–sulfide–silicate) medium at 4 GPa and 1400 °C. Journal of Mineralogical and Petrological Sciences. 2018. Vol. 113. Iss. 2, p. 59-67. DOI: 10.2465/jmps.170526

- Sonin V.M., Zhimulev E.I., Chepurov A.A. et al. Incipient stages of transformation of round natural diamonds under dissolution in Fe-S melt at high pressure. Lithosphere. 2019. Vol. 19. N 6, p. 945-952 (in Russian). DOI: 10.24930/1681-9004-2019-19-6-945-952

- Orlov Yu.L. Diamond Mineralogy (in Russian). Мoscow: Nauka, 1984, p. 170.

- Ragozin A., Zedgenizov D., Kuper K., Palyanov Y. Specific Internal Structure of Diamonds from Zarnitsa Kimberlite Pipe. Crystals. 2017. Vol. 7. Iss. 5. N 133. DOI: 10.3390/cryst7050133

- Khokhryakov A.F., Nechaev D.V., Sokol A.G. Microrelief of Rounded Diamond Crystals as an Indicator of the Redox Conditions of Their Resorption in a Kimberlite Melt. Crystals. 2020. Vol. 10. Iss. 3. N 233. DOI: 10.3390/cryst10030233

- Kostrovitsky S., Dymshits A., Yakovlev D. et al. Primary Composition of Kimberlite Melt. Minerals. 2023. Vol. 13. Iss 11. N 1404. DOI: 10.3390/min13111404

- Palyanov Yu.N., Khokhryakov A.F., Kupriyanov I.N. Crystallomorphological and Crystallochemical Indicators of Diamond Formation Conditions. Crystallography Reports. 2021. Vol. 66. N 1, p. 142-155. DOI: 10.1134/S1063774521010119

- Litvin Yu.A. Physicogeochemical Mechanisms of the Genesis of Matryoshka-Type Diamonds on the Basis of the Mantle-Carbonatite Theory. Geochemistry International. 2023. Vol. 61. N 3, p. 238-251. DOI: 10.1134/S0016702923030072

- Barnes S.J., Yudovskaya M.A., Iacono-Marziano G. et al. Role of volatiles in intrusion emplacement and sulfide deposition in the supergiant Norilsk-Talnakh Ni-Cu-PGE ore deposits. Geology. 2023. Vol. 51. N 11, p. 1027-1032. DOI: 10.1130/G51359.1

- Persikov E.S., Bukhtiyarov P.G., Sokol A.G. Change in the viscosity of kimberlite and basaltic magmas during their origin and evolution (prediction). Russian Geology and Geophysics. 2015. Vol. 56. N 6, p. 885-892. DOI: 10.1016/j.rgg.2015.05.005

- Litvin Yu.A. The physicochemical conditions of diamond formation in the mantle matter: experimental studies. Russian Geology and Geophysics. 2009. Vol. 50. N 12, p. 1188-1200. DOI: 10.1016/j.rgg.2009.11.017

- Masaitis V.L., Futerhendler S.I., Gnevushev M.A. Diamonds in impactites of the Popigay meteoretic crator. Zapiski Vsesoyuznogo mineralogicheskogo obshchestva. 1972. Part 101, p. 108-112 (in Russian).

- Korsakov A.V., Shatsky V.S. Origin of graphite-coated diamonds from ultrahigh-pressure metamorphic rocks. Doklady Earth Sciences. 2004. Vol. 399. N 8, p. 1160-1163.

- Fedortchouk Y. A new approach to understanding diamond surface features based on a review of experimental and natural diamond studies. Earth-Science Reviews. 2019. Vol. 193, p. 45-65. DOI: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2019.02.013

- Sonin V., Leech M., Chepurov A. et al. Why are diamonds preserved in UHP metamorphic complexes? Experimental evidence for the effect of pressure on diamond graphitization. International Geology Review. 2019. Vol. 61. Iss. 4, p. 504-519. DOI: 10.1080/00206814.2018.1435310

- Korsakov A.V., Zhimulev E.I., Mikhailenko D.S. et al. Graphite pseudomorphs after diamonds: An experimental study of graphite morphology and the role of H2O in the graphitisation process. Lithos. 2015. Vol. 236-237, p. 16-26. DOI: 10.1016/j.lithos.2015.08.012

- Gernon T.M., Gilbertson M.A., Sparks R.S.J., Field M. The role of gas-fluidisation in the formation of massive volcaniclastic kimberlite. Lithos. 2009. Vol. 112. Suppl. 1, p. 439-451. DOI: 10.1016/j.lithos.2009.04.011

- Sutao Zhao, Poli S., Schmidt M.W. et al. An experimental determination of the liquidus and a thermodynamic melt model in the CaCO3-MgCO3 binary, and modelling of carbonated mantle melting. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 2022. Vol. 336, p. 394-406. DOI: 10.1016/j.gca.2022.08.014

- Kang N., Schmidt M.W., Poli S. et al. Melting of siderite to 20 GPa and thermodynamic properties of FeCO3-melt. Chemical Geology. 2015. Vol. 400, p. 34-43. DOI: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2015.02.005

- Irving A.J., Wyllie P.J. Subsolidus and melting relationships for calcite, magnesite and the join CaCO3-MgCO3 36 kb. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 1975. Vol. 39. Iss. 1, p. 35-53. DOI: 10.1016/0016-7037(75)90183-0