Reagent treatment of fluorin-containing wastewater from the processing industry

- 1 — Engineer Dmitry Mendeleev University of Chemical Technology of Russia ▪ Orcid

- 2 — Engineer Institute of Comprehensive Exploitation of Mineral Resources RAS ▪ Orcid

- 3 — Ph.D. Head of Laboratory Dmitry Mendeleev University of Chemical Technology of Russia ▪ Orcid

- 4 — Ph.D., Dr.Sci. Head of Department Dmitry Mendeleev University of Chemical Technology of Russia ▪ Orcid

- 5 — Ph.D., Dr.Sci. Dean Dmitry Mendeleev University of Chemical Technology of Russia ▪ Orcid

Abstract

Fluorine‑containing wastewater is one of the main problems of the mining and processing industries. Mining, dressing, and sulphuric acid digestion of apatite concentrate – all these processes are accompanied by the generation of vast amounts of wastewater with elevated fluoride content, which pose a serious threat to the environment. Conventional methods do not always allow achieving the required discharge standards, which in turn necessitates the search for alternative reagents. The main objective of this work is to assess the possibility of using waste from the mining and smelting sector (phosphochalk, magnesia scrap, dust from gas cleaning units) as precipitating reagents for the first stage of fluoride ion removal, followed by tertiary treatment with complex titanium‑containing coagulants. We conducted experiments to select reagents and their dosages, the use of which will allow achieving the lowest residual fluoride concentrations in water. We found that using calcium/magnesium hydroxides does not allow meeting the standards for residual fluoride anion content. To achieve maximum precipitation efficiency, a 30 % excess of precipitating reagents is required. The study confirms that large‑volume mineral waste can serve as precipitating reagents for fluoride ion, with treatment efficiencies of 94 % for phosphochalk, 90 % for magnesia refractory scrap, and 99 % for gas cleaning units. We proved the effectiveness of complex titanium‑containing coagulants for water defluorination in comparison with conventional coagulants (aluminium oxychloride/aluminium sulphate). The use of a complex reagent not only significantly reduces coagulant consumption and minimizes residual fluoride anion content, but also substantially intensifies precipitation (by 1.5-1.75 times) and filtration of coagulation sludges (by 1.25-1.5 times). The developed conceptual diagram for wastewater defluorination using large‑volume waste and complex titanium‑containing reagents allows significantly reducing the level of negative environmental impact and taking a step towards implementing the circular economy concept.

Introduction

The rapid population growth and increasing level of urban industrialization place enormous strain on production facilities, leading to high consumption of raw materials, energy, and especially clean freshwater. The heavy burden on the industrial sector contributes to a rise in environmental impact due to the generation of substantial volumes of wastewater and a wide range of industrial waste [1].

Mining enterprises are among the main sources of complex-chemical-composition industrial wastewater. For example, the majority of enterprises engaged in the extraction and dressing of apatite-nepheline ore are in the Murmansk Region [2]. It is known that producing 1 ton of apatite concentrate requires processing more than 2 tons of pre-crushed apatite-nepheline ore. This process generates vast amounts of mineral waste – tailings – of which over 900 million tons have already been accumulated. Dressing is typically carried out using the flotation method with flotation agents (fatty acids such as tall oil and its derivatives), which helps recover apatite in the froth product destined for consumers [3]. Production of apatite concentrate generates large volumes of wastewater. These waters contain flotation reagents, fluorides, phosphates, and strontium. Such wastewater accumulates in tailings dams – often located near residential areas – and is also discharged into water bodies without adequate treatment, causing significant pollution of surface- and groundwater [4]. Another source of wastewater is enterprises processing apatite raw materials [5]. For instance, the production of wet‑process phosphoric acid, based on sulphuric acid digestion of apatite concentrate, generates large quantities of acidic fluoride‑containing wastewater. Discharging this wastewater into water bodies or municipal sewage systems without prior treatment is unacceptable due to its extremely low pH (below 2) and exceedance of maximum permissible concentration (MPC) limits for fishery waters with respect to fluorides [6].

According to the State Report on the Environmental Condition of the Russian Federation for 2023, approximately 123.6 million m3 of polluted and insufficiently treated wastewater are discharged annually in the Murmansk Region. Of this volume, about 15-20 million m3 consist of fluoride‑containing effluents from apatite mining and phosphoric acid production facilities. The concentration of fluoride ions in these effluents regularly exceeds existing standards by tens of thousands of times. In some cases, it reaches 25 g/dm3, while the MPC for fishery purposes is only 0.75 mg/dm3. Fluorides are in the list of priority pollutants of regional water bodies, alongside heavy metals and organic compounds. In 2023, 90 cases of high pollution and 34 cases of extremely high pollution of water bodies were registered. Of these, 16 cases of exceedance were specifically attributed to fluoride compounds.

The development and implementation of modern wastewater treatment technologies that meet regulatory requirements will help minimize the negative impact on water bodies in the Murmansk Region. Although some treated water may be recycled back into the production process, the primary objective remains ensuring the safe discharge of effluents into the environment in compliance with existing standards. Currently, the treatment of fluoride‑containing wastewater is a topical issue that is closely linked to environmental protection [7].

Several main methods are used to remove fluoride ions from water:

- ion exchange; a key drawback of this water treatment process is the need to dispose of large volumes of regenerating solutions and the complexity of handling them [8];

- membrane method; the main disadvantage of the membrane method is the need to use specific membrane materials resistant to strongly acidic fluoride‑containing effluents, which leads to enormous capital and operational costs [9];

- coagulation method for removing fluoride ions from water using coagulants based on Al and Fe has been known for quite a long time [10]. It is advisable to use this method as the final treatment stage when fluoride content in water does not exceed 25 mg/dm3. It envisages the use ofcomplex coagulants (e.g., aluminosilicate) or titanium-containing coagulants [11-13]. Complex reagents significantly outperform traditional analogues and do not have their drawbacks [14, 15];

- chemical precipitation using calcium- and magnesium-containing reagents in the form of CaF2/MgF2 is the most cost-effective and efficient method for treating wastewater with high fluoride ion content [16-18].

The process of fluoride anion removal is represented by the following reactions:

In industrial practice, 10 % suspensions of calcium hydroxide or calcium oxide are used to remove fluorides from water [17]. A promising alternative to conventional reagents could be the use of calcium- or magnesium-containing industrial wastes for treating fluoride-bearing wastewater generated at ore dressing plants.

Enterprises in the mining and smelting sector generate various types of waste, including slags, oil-contaminated scale, sludges, and dusts [19]. Open-source studies report on the reuse of these waste types to produce secondary products [20-22]. To a lesser extent, wastes from ironworks are recycled – specifically, dust from gas cleaning units of electric arc furnaces (EAF) captured by aspiration systems. According to literature, the chemical composition of this waste consists of more than 35 % calcium compounds (CaR, where R is the anionic part: ОН–, О2–, or СО32–). This, in turn, indicates the potential for using this waste as a reagent to treat highly concentrated fluoride‑bearing wastewater.

An alternative reagent for fluoride removal from water can be magnesium‑containing waste from the production and consumption of refractory materials (broken and scrap bricks, dusts), which consist of more than 75 % MgO and also contain to 5 % CaO. One promising reagent for precipitating fluoride anions is also a by-product of the integrated processing of phosphogypsum into ammonium sulphate – phosphochalk, whose main component is calcium carbonate [17]:

The use of waste from mining and processing industries as reagents for wastewater treatment, in particular, in water defluorination, is of notable interest and requires experimental validation [23].

Methods

The main objective of this work is to assess the feasibility of using various large‑volume wastes as fluoride precipitants, as well as to evaluate the efficiency of coagulation‑based tertiary water treatment to meet the MPC standards for fishery water bodies.

Tightening legislation in the field of large-volume waste management is encouraging enterprises to process these materials. There are numerous technologies for processing this group of waste (e.g., as an additive to construction materials, fertilizers, etc.), yet unfortunately, only a small portion of them are actually implemented. Most of the annually generated waste is sent to temporary storage facilities (slag/sludge ponds) and has a serious long-term negative impact on the environment. Within the scope of the presented experiments, these wastes were used for the first time as reagents for defluorination of wastewater, which determines a high level of scientific novelty and practical significance.

The wastes used in this study were samples of large-volume mineral wastes that did not found widespread practical application and are typically sent to designated landfill sites for disposal:

- phosphochalk; for prevention of REE migration into the liquid phase, phosphochalk samples were obtained from phosphogypsum that had undergone preliminary REE removal. In the absence of preliminary REE extraction, migration into the solution is prevented due to the formation of insoluble fluoride compounds;

- electric arc furnace gas cleaning dust;

- magnesia refractory scrap.

Despite the fact that these wastes are used as additives in construction materials, their application is limited by several factors – namely, the absence of approved technical specifications that regulate the composition of materials, their properties, and permissible areas of use, considering the variability of admixture components. Since these wastes are generated as a result of production processes and must be accounted for until they are incorporated into process regulations as raw materials, their use in construction materials may be restricted and potentially unsafe. This, in turn, necessitates a more detailed analysis of each batch.

The composition of the wastes used is presented in Table 1.

Table 1

Waste composition, %

|

Types of waste |

Oxides |

Other |

||||

|

MgO |

SiO2 |

Al2O3 |

CaO |

Fe2O3 |

||

|

Magnesia refractory scrap |

74.98 |

15.53 |

5.10 |

2.38 |

0.50 |

1.51 |

|

Phosphochalk |

1.79 |

1.27 |

0.87 |

35.50 |

1.51 |

59.06 |

|

Gas cleaning dust |

10.36 |

11.00 |

18.44 |

18.07 |

0.25 |

41.88 |

Classical suspensions of calcium and magnesium hydroxides, with 10 % active component content, were used as control precipitating reagents. The reagent was introduced based on the estimated Cа(OH)2/F– and Mg(OH)2/F– ratios from reactions (1) and (2). The contact time was 10 min, and the precipitation stage lasted 30 min. In the supernatant, the pH and residual fluoride ion content were filtered and determined. The fluoride ion content was determined potentiometrically using an ELIS-131F ion-selective electrode and an ESr‑10103 silver/silver chloride reference electrode, in accordance with regulatory document PND F 14.1:2:4.270-2012. pH control was performed using a portable I-160 ion meter with a glass indicator electrode, by the potentiometric method, in accordance with regulatory document PND F 14.1:2:3:4.121-97. Sulphate content in water was determined photometrically using the KFK-3 instrument, in accordance with PND F 14.1:2.159-2000. The suspended solids content in the supernatant after applying the precipitating reagent and flocculant was determined gravimetrically using Gosmetr VL-320S analytical balances, in accordance with RD 52.24.468-2019. The phase composition of the resulting products was determined using a DRON-3M X-ray diffractometer.

Defluorination (Jar-tests) was carried out using a Velp JLT 4 laboratory flocculator in polymer containers (to prevent the formation of SiF4). To ensure reproducibility of the results, the experimental methodology was based on key provisions from GOST 51642-2000, including the procedure for preparing and dosing the coagulant, mixing conditions, and the efficiency assessment criterion, which involves estimating the residual concentration of the pollutant (in this case, the fluoride ion). The chemical precipitation and coagulation comprised the following stages: rapid coagulation 2 min at 200 rpm; slow coagulation 8 min at 25 rpm; precipitation and sludge compaction 30 min. The sludge was separated by filtration through a blue ribbon paper filter (filtration rating 5 μm).

The filtration rate was measured by passing the coagulated liquid through a filter for 60 s. The sedimentation rate was evaluated after the coarse-phase settling was complete and the optical density of the supernatant liquid had stabilized. This 60-second method for assessing sludge filterability is used by water utilities as a standard test for comparative analysis of new coagulants’ effectiveness. This time interval allows obtaining reproducible results applicable in water treatment.

The study focused on wastewater from an absorption gas cleaning unit, generated during the digestion of apatite concentrate with sulphuric acid, containing 12.0 g/dm3 of fluoride ions and having a pH of 1.3.

The following widely used coagulants were selected: polyaluminium hydroxychloride Al2(ОН)5Cl (manufactured by OOO Akva-Aurat, TU 2163-077-00205067-2013) and aluminium sulphate Al2(SO4)3 (manufactured by OOO Akva-Aurat, TU 20.13.41-004-41654713-2014). As complex titanium-containing coagulants (CTC), the following samples were used: CTCs (a mixture of aluminium and titanium sulphates); CTCs-cl (a mixture of aluminium and titanium chlorides/sulphates); CTCcl (a mixture of aluminium and titanium chlorides) [24, 25]. The content of the titanium-containing modifying additive did not exceed 5 % (TiO2 equivalent) of the total dose of the aluminium-containing coagulant.

Discussion

At the first stage of the experiment, conventional calcium- and magnesium‑containing reagents in the form of 10 % suspensions of Ca(OH)2 and Mg(OH)2 were used to precipitate most of the fluorides (Table 2).

Table 2

Residual fluoride ion content after water treatment with Ca(OH)2 and Mg(OH)2 suspensions

|

Precipitating reagent |

Ca(OH)2/Mg(OH)2 : F– |

Residual concentration of [F–], mg/dm³ |

pH level after treatment |

|

|

Ca(OH)2 |

1:1 |

282.0 |

1.40 |

|

|

1.1:1 |

270.0 |

1.41 |

||

|

1.2:1 |

240.1 |

1.47 |

||

|

1.25:1 |

186.5 |

1.52 |

||

|

1.3:1 |

182.0 |

1.64 |

||

|

1.5:1 |

180.2 |

1.61 |

||

|

1.75:1 |

168.7 |

1.63 |

||

|

2:1 |

168.0 |

1.68 |

||

|

2.5:1 |

161.9 |

1.62 |

||

|

Mg(OH)2 |

1:1 |

1573.4 |

1.38 |

|

|

1.1:1 |

1460.2 |

1.42 |

||

|

1.2:1 |

1350.8 |

1.40 |

||

|

1.3:1 |

1109.9 |

1.49 |

||

|

1.5:1 |

1035.6 |

1.51 |

||

|

1.75:1 |

917.1 |

1.53 |

||

|

2:1 |

903.0 |

1.55 |

||

|

2.5:1 |

889.7 |

1.50 |

||

Note. According to the PND F 14.1:2:3:4.121‑97 methodology, pH measurement uncertainty is 0.2. The uncertainty of quantitative determination of fluoride ions is ± 5 %.

As the data in Table 2 show, the use of calcium hydroxide suspension (milk of lime) achieves the highest efficiency of fluoride removal from the solution (over 98 %), compared to magnesium hydroxide suspension (no more than 93 %). This phenomenon can be explained by the fact that the efficiency of fluoride removal primarily depends on two key factors: the nature of the reagent used, and consequently the formation of less soluble calcium fluoride (15 mg/dm3) compared to magnesium fluoride (76 mg/dm3), as well as the achieved pH value of the system. We note that at the stoichiometric ratio of Cа(OH)2/Mg(OH)2 : F– equal to 1:1, the actual efficiency was significantly lower due to low pH values.

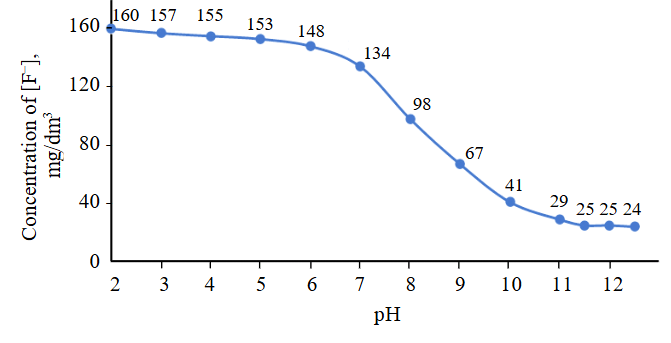

Since the next stage of the experiments involved assessing the effect of pH on fluoride ion removal efficiency, the system’s pH values were regulated solely by adjusting the dosage of Cа(OH)2 : F– suspension, without using additional alkaline reagents. This approach allowed us to exclude the influence of extraneous ions. The experimental results are presented in Fig.1.

Fluoride removal efficiency is directly dependent on the pH value. Precipitation is most effective when the system’s pH is at least 11.5. In this case, the optimal Cа(OH)2 : F– ratio was 4.7:1, which significantly exceeds the stoichiometric ratio. This excess of reagent is necessary to neutralize the initial acidity of the medium and maintain the system’s buf-fering capacity. If the pH exceeds 11.5, the efficiency increases only slightly, but the consumption of the precipitating reagent rises significantly (by 25-30 %), which in turn leads to an increase in sludge volume.

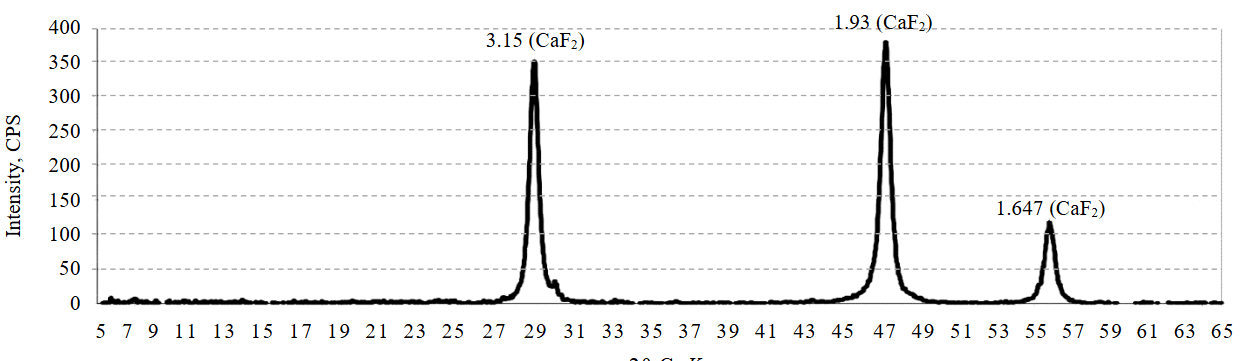

To confirm the binding of fluoride ions into insoluble calcium fluoride, we studied the phase composition of the precipitate after treating wastewater with milk of lime (Fig.2). The results of phase analysis of the precipitate sample obtained after the main stage of wastewater defluorination demonstrate that fluoride ions were bound into the insoluble compound CaF2 in the absence of intermediate forms (e.g., Ca(OH)F), which have higher solubility.

Fig.1. Dependence of residual fluoride ion content on pH

Fig.2. Diffractogram of the phase composition of the precipitate after the main treatment stage

Developing technical solutions focused on environmental protection and reducing reagent costs implies the rational use of all raw material components and energy. Therefore, within the scope of this work, we assessed the feasibility of using various mineral wastes as precipitating reagents in the first stage of wastewater defluorination. The experimental conditions were similar to those when using pure calcium or magnesium hydroxides. The data obtained from the experiment are presented in Table 3.

Table 3

Residual fluoride ion content after water treatment with mineral waste*

|

Waste |

∑Ca2+/Mg2+ : F– |

pH level after treatment |

Residual concentration of [F–], mg/dm3 |

|

|

Phosphochalk |

0.66 |

1.50 |

1290.0 |

|

|

0.88 |

1.56 |

1030.1 |

||

|

1.10 |

1.58 |

820.4 |

||

|

1.32 |

1.67 |

783.5 |

||

|

1.54 |

1.74 |

751.5 |

||

|

Magnesia refractory scrap |

0.31 |

1.55 |

1549.3 |

|

|

0.62 |

1.57 |

1450.1 |

||

|

0.93 |

1.60 |

1393.1 |

||

|

1.24 |

1.69 |

1267.5 |

||

|

1.55 |

1.84 |

1198.2 |

||

|

Gas cleaning dust from EAF emissions |

0.64 |

5.80 |

290.6 |

|

|

0.80 |

5.80 |

278.1 |

||

|

0.96 |

6.70 |

198.7 |

||

|

1.12 |

7.87 |

156.4 |

||

|

1.28 |

8.52 |

106.9 |

||

|

1.44 |

9.26 |

79.9 |

||

* See the note to Table 2.

Based on Table 3 data, we can conclude that the use of various anthropogenic wastes enables achieving a high degree of fluoride ion removal (over 99 % when using gas cleaning dust), which is close to the results of control experiments. Control experiments with pure reagents Ca(OH)2 and Mg(OH)2 provided a preliminary assessment of precipitation and justified the selection of mineral wastes as an alternative. Although some wastes showed lower defluorination efficiency – 93.7 % for phosphochalk and 90.0 % for magnesia refractory scrap – their application remains technologically and economically viable with further process optimization. For example, combining these wastes with a minimal addition of Ca(OH)2 could enhance purification efficiency.

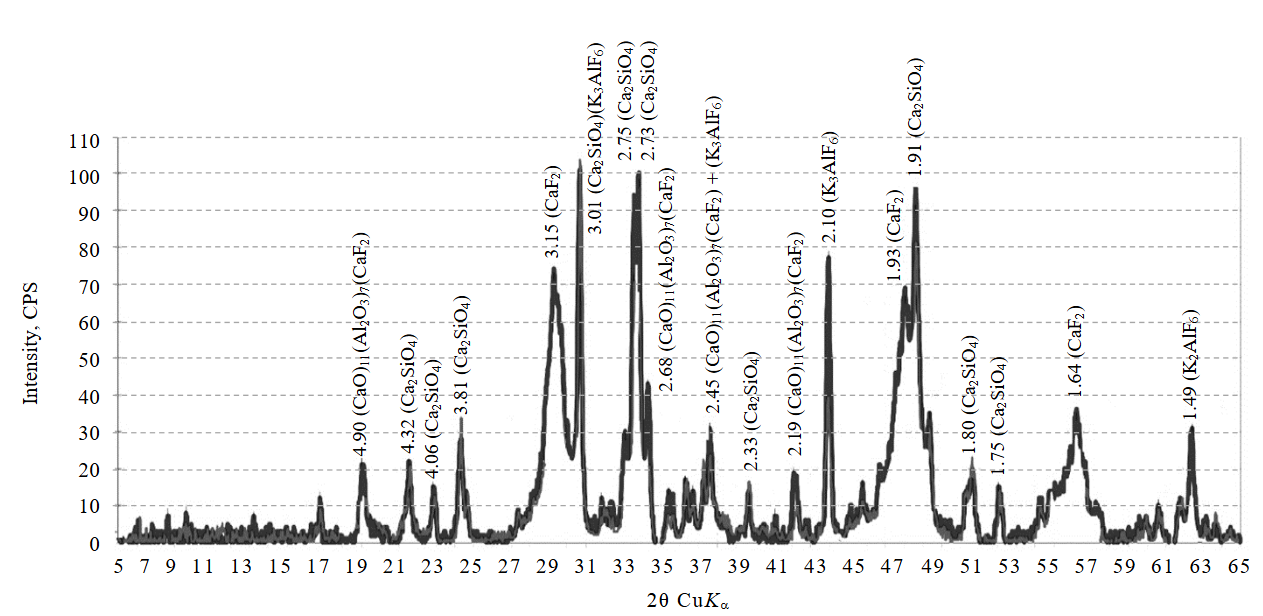

Since the main components of phosphochalk and magnesia scrap are calcium and magnesium compounds, the reaction products are predominantly calcium and magnesium fluorides. Given that the composition of the resulting compounds is clear and supported by literature data, the main research interest lies in studying the precipitate formed during the defluorination of wastewater using gas cleaning dust from EAF emissions.

To identify the compounds formed as a result of fluoride removal from wastewater using gas cleaning dust, we studied the phase composition of the resulting precipitate (Fig.3). According to the diffraction pattern data, the use of EAF gas cleaning dust enables conversion of fluorides into weakly crystallized calcium fluoride (more than 20 %). Additionally, the presence of calcium fluoroaluminate phase – 11CaO∙7Al2O3∙CaF2 (more than 30 %) and K3AlF6 (less than 5 %) was detected. Due to its composition, the resulting sludge can be used as a mineralizing additive to enhance the physico-chemical processes of calcium oxide assimilation that occur during clinker firing [26, 27]. This approach to utilizing the generated sludge will not only optimize production processes but also reduce the costs of natural mineral extraction, thereby lowering the cost of cement products [28, 29].

The reduced treatment efficiency when using magnesia scrap (89 %) is likely due to the larger particle size (290 μm versus 45 μm) compared to phosphochalk (93 % efficiency).

The use of phosphochalk in the defluorination of the model solution may be limited due to secondary water contamination with ammonium and sulphate ions, resulting from incomplete washing and residual traces of (NH4)2SO4 formed according to reaction (3). This disadvantage is eliminated at the site of secondary waste generation from phosphogypsum processing.

Since the individual use of gas cleaning dust from EAF emissions does not allow achieving the required discharge standards (residual fluoride concentration 79.9 mg/dm3), the next stage of the experiment required evaluating the feasibility of a combined method involving the joint use of the waste and milk of lime. The Ca(OH)2 suspension was introduced in the range of 2.5 % to 40 % by mass of the added waste, selected based on the previously determined optimal dose of dust (∑Cа2+/Mg2+: F–, ratio of 1.44:1). The experimental results are presented in Table 4.

Fig.3. Diffraction pattern of the phase composition of the precipitate after the main treatment stage using EAF dust

Table 4

Evaluation of the efficiency of the combined method at a waste ratio of ∑Cа2+/Mg2+ : F– 1,44:1*

|

Quantity of Ca(OH)2, % |

pH level after treatment |

Residual concentration of [F–], mg/dm3 |

|

0 |

9.26 |

79.9 |

|

2.5 |

9.78 |

64.5 |

|

5.0 |

10.27 |

50.6 |

|

7.5 |

10.75 |

41.4 |

|

10.0 |

11.05 |

34.9 |

|

12.5 |

11.37 |

27.1 |

|

15.0 |

11.49 |

27.1 |

|

17.5 |

11.64 |

27.4 |

|

20.0 |

11.78 |

27.5 |

|

25.0 |

12.10 |

27.5 |

* See note to Table 2.

The introduction of milk of lime at a dosage of 12.5 % (in terms of the active component) relative to the mass of gas cleaning dust allows achieving a residual fluoride ion concentration of 27.1 mg/dm3 at a pH value of 11.37. This is confirmed by previous experiments with pure reagents, where maximum efficiency was attained within the pH range of 11.0-11.5. A further increase in the Ca(OH)2 dosage (>15 %) does not lead to a significant reduction in fluoride concentration, despite the pH rising to 12.1. The obtained data demonstrate the feasibility of jointly using gas cleaning waste and milk of lime for fluoride removal. In this process, both the stoichiometric ratio of components and the achieved pH value of the system play a key role. Thus, the use of industrial waste as a precipitating reagent will allow some enterprises in the mining, smelting, and chemical sectors to take a step towards implementing the Zero Waste concept.

Despite the high degree of treatment, the residual fluoride ion concentration remains too high both for returning to the production process cycle and for discharge into sewage systems or water bodies. The water that had undergone the stage of precipitating most fluoride ions using the combined method was post-treated by coagulation. The stoichiometric dosage of reagents was estimated according to the following reactions:

The efficiency of fluoride ion removal by chemical precipitation and coagulation largely depends on the pH of the medium. The optimal pH values for achieving maximum treatment efficiency may vary depending on the reagent used [30]. If necessary, pH adjustment was performed using a 1 % solution of NaOH/HCl. The results of experiments on tertiary treatment of wastewater to remove fluoride ions (initial concentration 27.1 mg/dm3) using conventional coagulants are presented in Table 5. Fluoride ion removal from aqueous solutions during coagulation becomes more intensive as the pH of the medium decreases. This phenomenon is explained by the ability of amphoteric aluminium hydroxide sol Al(OH)3 to exhibit basic/acidic properties, which directly depend on the pH of the medium. In acidic media (pH < 5.0), the predominant aluminium forms are Al3+ions, which effectively interact with fluoride ions to form sparingly soluble AlF3 compounds as well as mixed hydroxofluoride complexes Al(OH)хF3-х. At the same time, the positive charge on the surface of flocs ≡Al–OH2+ promotes additional adsorption of F–. In weakly alkaline media (pH 7.5-8.0), the prevalence of anionic forms Al(OH)2O– and Al(OH)4– leads to electrostatic repulsion of fluorides and reduced treatment efficiency. Thus, the optimal pH values for coagulation lie in the range of 4.5-5.0 [31].

Table 5

Effectiveness of traditional aluminium‑containing coagulants in the defluorination of wastewater*

|

Al2(SO4)3 |

Al2(OН)5Cl |

||||||

|

Al/F |

pH level after adjustment |

Residual F– concentration, mg/dm3 |

Treatment efficiency, % |

Al/F |

pH level after adjustment |

Residual F– concentration, mg/dm3 |

Treatment efficiency, % |

|

Initial |

11.2* |

27.1 |

– |

Initial |

11.2* |

27.1 |

– |

|

1.1:1 |

7.00 |

23.8 |

4.9 |

1.25:1 |

7.00 |

25.0 |

0 |

|

1.2:1 |

6.00 |

7.7 |

69.4 |

1.5:1 |

5.64 |

11.8 |

52.8 |

|

1.3:1 |

5.87 |

3.1 |

87.8 |

1.75:1 |

5.02 |

4.5 |

82.0 |

|

1.4:1 |

5.78 |

2.1 |

91.6 |

2:1 |

4.92 |

3.6 |

85.6 |

|

1.5:1 |

5.16 |

1.9 |

92.5 |

3:1 |

4.80 |

3.0 |

88.2 |

|

2:1 |

4.79 |

1.8 |

92.9 |

3.5:1 |

4.83 |

2.3 |

90.9 |

|

2.5:1 |

4.66 |

1.5 |

94.1 |

4:1 |

4.68 |

2.1 |

91.6 |

|

3:1 |

4.50 |

1.4 |

94.4 |

4.5:1 |

4.56 |

1.5 |

94.0 |

|

|

|

|

|

5:1 |

4.49 |

1.3 |

94.8 |

* See note to Table 2.

Analysis of the results presented in Table 5 showed that increasing the coagulant consumption leads to a significant reduction in fluoride concentration. To achieve the permissible fluoride ion content (in accordance with Order N 552 of the Ministry of Agriculture of the Russian Federation dated 13.12.2016, as amended on 13.06.2024), it is necessary to add 250 % of the stoichiometrically estimated amount of aluminium sulphate and 450 % of aluminium oxychloride. This, in turn, results in excessive consumption of aluminium-containing reagents and an increase in the volume of coagulation sludge.

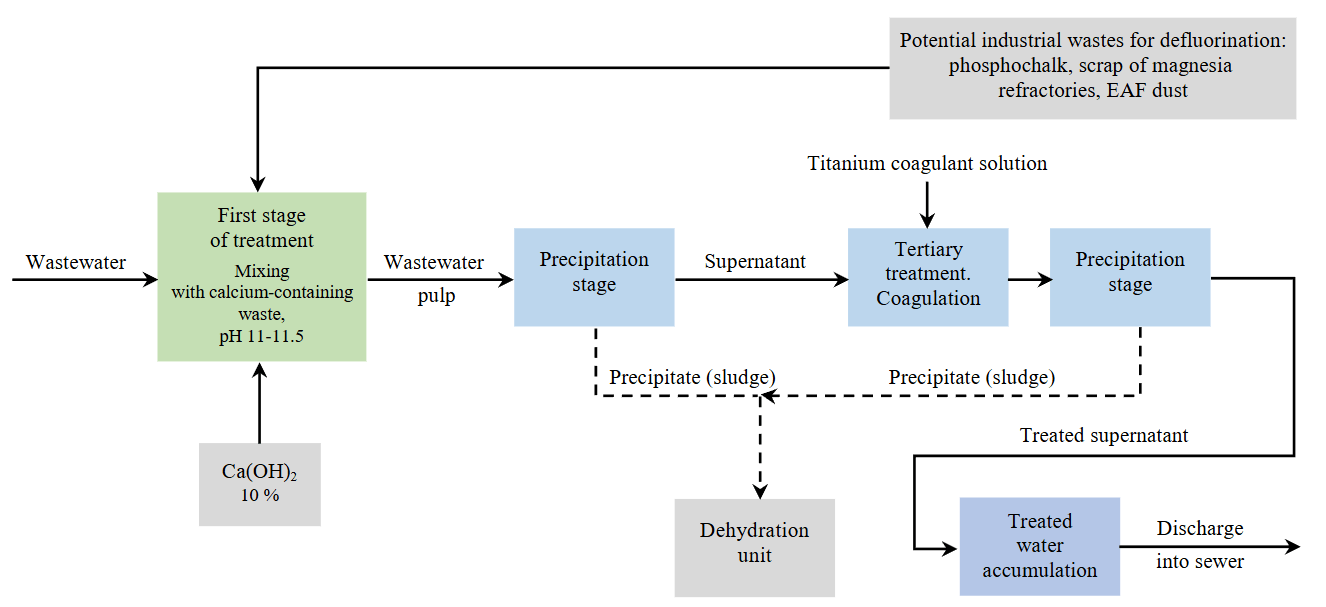

Based on the data obtained during the study, we designed a process flow diagram for reagent‑based treatment of wastewater to remove fluorine compounds (Fig.4).

To assess the potential for reducing coagulant consumption at the tertiary treatment stage, a series of experiments was conducted using complex titanium‑containing coagulants, which demonstrated high efficiency in treating wastewater with complex compositions [32-34].

Data on the effectiveness of complex titanium-containing coagulants in removing fluorides from wastewater, compared to conventional reagents, are presented in Table 6. The use of all forms of complex titanium-containing coagulants achieves higher treatment efficiency with significantly lower reagent consumption compared to individual aluminium‑containing coagulants.

Fig.4. Conceptual diagram of the reagent‑based wastewater defluorination

Table 6

Residual fluoride ion content after using CTC*

|

(Al+Ti)/F ratio |

pH level after adjustment |

Residual F– concentration, mg/dm3 |

|

CTCs (aluminium sulphate + 10 % TiOSO4) |

||

|

1:1 |

5.31 |

1.70 |

|

1.1:1 |

5.30 |

1.57 |

|

1.3:1 |

5.28 |

0.88 |

|

1.5:1 |

5.18 |

0.25 |

|

CTCs-cl (aluminium sulphate/oxychloride 3:1 + 10 % TiOSO4) |

||

|

1:1 |

5.23 |

1.68 |

|

1.1:1 |

5.19 |

1.28 |

|

1.3:1 |

5.18 |

0.74 |

|

1.5:1 |

4.98 |

0.21 |

|

CTCcl (aluminium oxychloride + 10 % TiCl4) |

||

|

1:1 |

5.16 |

1.71 |

|

1.1:1 |

5.14 |

1.14 |

|

1.5:1 |

5.10 |

0.74 |

|

2:1 |

5.03 |

0.52 |

*See note to Table 2.

Enhanced efficiency of complex titanium‑containing reagents is due to a combination of several effects. The developed surface area of titanium compound hydrolysis products promotes intensification of adsorption for contaminants on their surface. Additional efficiency gains result from nucleation of micelles formed by negatively charged insoluble titanium compounds (in particular, meta‑ and orthotitanic acids, TiO2·nH2O) and positively charged colloidal particles of aluminium hydroxide [35, 36]. The residual cation content of the coagulant (aluminium/titanium) met the MPC requirements only when complex titanium-containing coagulants were used (less than 0.04 mg/dm3 for aluminium and less than 0.1 mg/dm3 for titanium).

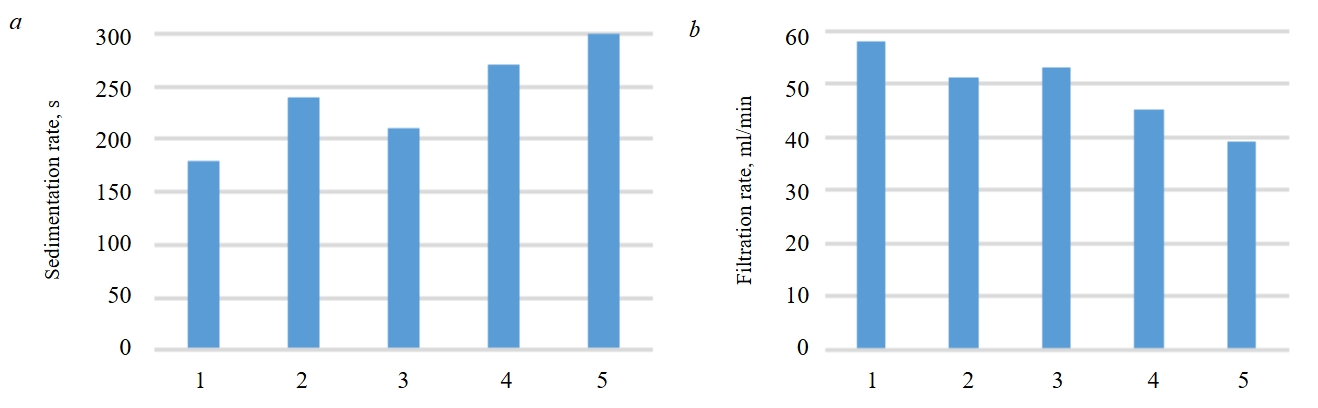

During the separation of coagulation sludges, we observed that their sedimentation and filtration rates (when using CTCs-cl and CTCcl) were significantly higher compared to conventional coagulants (aluminium sulphate, aluminium oxychloride) (Fig.5). Specifically, the sedimentation rate increased by a factor of 1.5-1.75 on average, while the filtration rate rose by a factor of 1.25-1.5.

Intensification of coagulation sludge sedimentation and filtration is attributed to polycondensation of titanium compound hydrolysis products (flocculation) leading to the formation of polymer bridges between meta‑ and orthotitanic acid structures, as well as initially formed aluminium hydroxide particles. This results in larger particles with higher sedimentation rates [37, 38].

Fig.5. Sedimentation rate (a) and filtration rate (b) of coagulation sludges

1 – CTCs-cl; 2 – CTCs; 3 – CTCcl; 4 – aluminium sulphate; 5 – aluminium oxychloride

Chemical composition of the precipitate obtained during coagulation (a mixture of insoluble fluorides of calcium, aluminium, and titanium) when using complex titanium‑containing coagulants corresponds to Class 5 hazardous waste (non‑hazardous). This allows for safe disposal in waste landfills with minimal environmental impact. Additionally, the precipitate can be treated with concentrated sulphuric acid solutions to produce hydrogen fluoride [39].

Conclusion

We examine the precipitation of fluoride ions from highly concentrated fluoride‑containing wastewater (12.0 g/dm3 of fluoride ions). The research confirms that industrial waste from the mining and smelting sector can serve as effective precipitating reagents in wastewater defluorination. The treatment efficiency reaches 93.7 % with phosphochalk, 90 % with magnesia refractory scrap, and 99.3 % with gas cleaning units.

The study shows that a combined treatment method, which integrates industrial waste and chemical reagents (EAF gas cleaning dust + Ca(OH)2 at an optimal ratio of 1.44:1 (∑Cа2+/Mg2+: F–) plus a 12.5 % milk of lime additive, achieves a residual fluoride concentration of 27.1 mg/dm3.

Implementing wastewater treatment with mineral waste offers two key benefits. It minimizes environmental impact and enables the use of generated sludges as secondary raw materials in the cement industry. This approach represents a step toward the Zero Waste concept.

We identified optimal conditions for tertiary wastewater treatment to meet regulatory standards using both conventional aluminium-containing and innovative complex titanium-containing coagulants. We found that complex coagulants reduce reagent consumption by 1.5-2.5 times and significantly accelerate the removal of generated precipitate.

Using a complex coagulant with an Al+Ti/F ratio of 1.1:1 achieves fluoride ion discharge standards in accordance with Order N 552 of the Ministry of Agriculture of the Russian Federation dated 13.12.2016 (as amended on 13.06.2024).

References

- de Mello Santos V.H., Campos T.L.R., Espuny M., de Oliveira O.J. Towards a green industry through cleaner production development. Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 2022. Vol. 29. Iss. 1, p. 349-370. DOI: 10.1007/s11356-021-16615-2

- Dauvalter V.A. Lakes hydrochemistry in the zone of influence of iron-mining industry waste waters. Vestnik of MSTU. 2019. Vol. 22. N 1, p. 167-176 (in Russian). DOI: 10.21443/1560-9278-2019-22-1-167-176

- Goryachev A.A., Krasavtseva E.A., Lashchuk V.V. et al. Assessment of the Environmental Hazard and Possibility of Processing of Refinement Tailings of Loparite Ores Concentration. Ecology and Industry of Russia. 2020. Vol. 24. N 12, p. 46-51 (in Russian). DOI: 10.18412/1816-0395-2020-12-46-51

- Pashkevich M.A., Chukaeva M.A. Assessment and reduction of the JSC “Apatite” negative impact on surface water. Mining Informational and Analytical Bulletin. 2015. N 10, p. 377-381 (in Russian).

- Pasechnik L.A., Shirokova A.G., Yatsenko S.P., Mediankina I.S. Concentration and purification of rare metals during the recycling of technogenic wastes. Transactions of the Kola Science Centre of RAS. 2015. N 5 (31), p. 186-189 (in Russian).

- Joshi A.N. A review of processes for separation and utilization of fluorine from phosphoric acid and phosphate fertilizers. Chemical Papers. 2022. Vol. 76. Iss. 10, p. 6033-6045. DOI: 10.1007/s11696-022-02323-9

- Belikov M.L., Lokshin E.P. Effective and affordable methods of cleaning a variety of water sources from the fluorine-containing inorganic impurities. Tsvetnye metally. 2020. N 3, p. 79-85 (in Russian). DOI: 10.17580/tsm.2020.03.12

- Millar G.J., Couperthwaite S.J., Wellner D.B. et al. Removal of fluoride ions from solution by chelating resin with imino-diacetate functionality. Journal of Water Process Engineering. 2017. Vol. 20, p. 113-122. DOI: 10.1016/j.jwpe.2017.10.004

- Yangbo Qiu, Long-Fei Ren, Jiahui Shao et al. An integrated separation technology for high fluoride-containing wastewater treatment: Fluoride removal, membrane fouling behavior and control. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2022. Vol. 349. N 131225. DOI: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.131225

- Shuo Li, Mengjie Liu, Fuming Meng et al. Removal of F− and organic matter from coking wastewater by coupling dosing FeCl3 and AlCl3. Journal of Environmental Sciences. 2021. Vol. 110, p. 2-11. DOI: 10.1016/j.jes.2021.03.009

- Jinjun Deng, Zeyu Gu, Lingmin Wu et al. Efficient purification of graphite industry wastewater by a combined neutralization-coagulation-flocculation process strategy: Performance of flocculant combinations and defluoridation mechanism. Separation and Purification Technology. 2023. Vol. 326. N 124771. DOI: 10.1016/j.seppur.2023.124771

- Zhiwei Lin, Xuezhi Li, Chunhui Zhang et al. Ti-doped fly ash aluminum iron based composite coagulant for efficient fluoride removal from mine drainage over a wide pH range. Journal of Water Process Engineering. 2024. Vol. 67. N 106152. DOI: 10.1016/j.jwpe.2024.106152

- Jianfeng Zhang, Brutus T.E., Jiemin Cheng, Xiaoguang Meng. Fluoride removal by Al, Ti, and Fe hydroxides and coexisting ion effect. Journal of Environmental Sciences. 2017. Vol. 57, p. 190-195. DOI: 10.1016/j.jes.2017.03.015

- Yonghai Gan, Jingbiao Li, Li Zhang et al. Potential of titanium coagulants for water and wastewater treatment: Current status and future perspectives. Chemical Engineering Journal. 2021. Vol. 406. N 126837. DOI: 10.1016/j.cej.2020.126837

- Thomas M., Bąk J., Królikowska J. Efficiency of titanium salts as alternative coagulants in water and wastewater treatment: short review. Desalination and Water Treatment. 2020. Vol. 208, p. 261-272. DOI: 10.5004/dwt.2020.26689

- Tafu M., Arioka Y., Takamatsu S., Toshima T. Properties of sludge generated by the treatment of fluoride-containing wastewater with dicalcium phosphate dehydrate. Euro-Mediterranean Journal for Environmental Integration. 2016. Vol. 1. N 4. DOI: 10.1007/s41207-016-0005-6

- Pérez-Moreno S.M., Romero C., Guerrero J.L. et al. Evolution of the waste generated along the cleaning process of phosphogypsum leachates. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering. 2023. Vol. 11. Iss. 6. N 111485. DOI: 10.1016/j.jece.2023.111485

- El Diwani G., Amin Sh.K., Attia N.K., Hawash S.I. Fluoride pollutants removal from industrial wastewater. Bulletin of the National Research Centre. 2022. Vol. 46. N 143. DOI: 10.1186/s42269-022-00833-w

- Urbanovich N.I., Korneev S.V., Volosatikov V.I., Komarov D.O. Analysis of the composition and processing techno-logies of dispersed iron containing waste. Foundry production and metallurgy. 2021. N 4, p. 66-69 (in Russian). DOI: 10.21122/1683 6065 2021 4 66 69

- Leontev L.I., Ponomarev V.I., Sheshukov O.Yu. Recycling and Disposal of Industrial Waste from Metallurgical Production. Ecology and Industry of Russia. 2016. Vol. 20. N 3, p. 24-27 (in Russian). DOI: 10.18412/1816-0395-2016-3-24-27

- Sverguzova S.V., Sapronova Zh.A., Zubkova O.S. et al. Electric steelmaking dust as a raw material for coagulant production. Journal of Mining Institute. 2023. Vol. 260, p. 279-288. DOI: 10.31897/PMI.2023.23

- Lacson C.F.Z., Ming-Chun Lu, Yao-Hui Huang. Fluoride-rich wastewater treatment by ballast-assisted precipitation with the selection of precipitants and discarded or recovered materials as ballast. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering. 2021. Vol. 9. N 4. N 105713. DOI: 10.1016/j.jece.2021.105713

- Li Wang, Ye Zhang, Ning Sun et al. Precipitation Methods Using Calcium-Containing Ores for Fluoride Removal in Wastewater. Minerals. 2019. Vol. 9. Iss. 9. N 511. DOI: 10.3390/min9090511

- Kuzin Е.N. Preparation and use of complex titanium-containing coagulant from quartz-leucoxene concentrate. Journal of Mining Institute. 2024. Vol. 267, p. 413-420.

- Kuzin E. Synthesis and Use of Complex Titanium-Containing Coagulant in Water Purification Processes. Inorganics. 2025. Vol. 13. Iss. 1. N 9. DOI: 10.3390/inorganics13010009

- Novosyolov A.G., Dreer Yu.I., Novoselova I.N., Levina Yu.A. Study of the mineralizing effect of cryolite and its influence on the processes of clinker formation. Bulletin of Belgorod State Technological University named after V.G.Shoukhov. 2023. N 11, p. 82-92 (in Russian). DOI: 10.34031/2071-7318-2023-8-11-82-92

- Koehler A., Neubauer J., Goetz-Neunhoeffer F. How C12A7 influences the early hydration of calcium aluminate cement at different temperatures. Cement and Concrete Research. 2022. Vol. 162. N 106972. DOI: 10.1016/j.cemconres.2022.106972

- Jian Liu, Xiaoli Ji, Qi Luo et al. Improvement of early age properties of Portland cement by ternary hardening-accelerating admixture. Magazine of Concrete Research. 2019. Vol. 73. Iss. 4, p. 195-203. DOI: 10.1680/jmacr.19.00148

- Matinde E., Simate G.S., Ndlovu S. Mining and metallurgical wastes: a review of recycling and re-use practices. Journal of the Southern African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy. 2018. Vol. 118. N 8, p. 825-844. DOI: 10.17159/2411-9717/2018/v118n8a5

- Xiaofeng Tang, Chengyun Zhou, Wu Xia et al. Recent advances in metal–organic framework-based materials for removal of fluoride in water: Performance, mechanism, and potential practical application. Chemical Engineering Journal. 2022. Vol. 446. Part 3. N 137299. DOI: 10.1016/j.cej.2022.137299

- Yonghai Gan, Li Zhang, Shujuan Zhang. The suitability of titanium salts in coagulation removal of micropollutants and in alleviation of membrane fouling. Water Research. 2021. Vol. 205. N 117692. DOI: 10.1016/j.watres.2021.117692

- Shon H.K., Vigneswaran S., Kandasamy J. et al. Preparation and Characterization of Titanium Dioxide (TiO2) from Sludge produced by TiCl4 Flocculation with FeCl3, Al2(SO4)3 and Ca(OH)2 Coagulant Aids in Wastewater. Separation Science and Technology. 2009. Vol. 44. Iss. 7, p. 1525-1543. DOI: 10.1080/01496390902775810

- Kuzin E.N., Kruchinina N.E. Titanium-containing coagulants for foundry wastewater treatment. CIS Iron and Steel Review. 2020. Vol. 20. N 2, p. 66-69. DOI: 10.17580/cisisr.2020.02.14

- Azopkov S.V., Kuzin E.N., Kruchinina N.E. Study of the Efficiency of Combined Titanium Coagulants in the Treatment of Formation Waters. Russian Journal of General Chemistry. 2020. Vol. 90. N 9, p. 1811-1816. DOI: 10.1134/S1070363220090364

- Hossain S.M., Park M.J., Park H.J. et al. Preparation and characterization of TiO2 generated from synthetic wastewater using TiCl4 based coagulation/flocculation aided with Ca(OH)2. Journal of Environmental Management. 2019. Vol. 250. N 109521. DOI: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.109521

- Yonghai Gan, Jingbiao Li, Li Zhang et al. Potential of titanium coagulants for water and wastewater treatment: Current status and future perspectives. Chemical Engineering Journal. 2021. Vol. 406. N 126837. DOI: 10.1016/j.cej.2020.126837

- Zhiwei Lin, Xuezhi Li, Chunhui Zhang et al. Ti-doped fly ash aluminum iron based composite coagulant for efficient fluoride removal from mine drainage over a wide pH range. Journal of Water Process Engineering. 2024. Vol. 67. N 106152. DOI: 10.1016/j.jwpe.2024.106152

- Beibei Liu, Baoyu Gao, Kangying Guo et al. The interactions between Al (III) and Ti (IV) in the composite coagulant polyaluminum-titanium chloride. Separation and Purification Technology. 2022. Vol. 282. Part B. N120148. DOI: 10.1016/j.seppur.2021.120148

- Hang Zhao, Xiaoguang Zhang, De’an Pan. Research progress on comprehensive utilization of fluorine-containing solid waste in the lithium battery industry. Green Manufacturing Open. 2024. Vol. 2. Iss. 3. N 15. DOI: 10.20517/gmo.2024.070201