On the need to refine triaxial testing methods for investigating the mechanical behaviour of salt rocks and salt-based geomaterials

- 1 — Postgraduate Student Belarusian State University ▪ Orcid ▪ Elibrary ▪ Scopus ▪ ResearcherID

- 2 — Ph.D., Dr.Sci. Head of Department Belarusian State University ▪ Orcid ▪ Elibrary ▪ Scopus ▪ ResearcherID

- 3 — Ph.D. Head of Department LLC ProTech Engineering ▪ Orcid ▪ Elibrary

Abstract

This paper addresses the necessity of refining standard triaxial testing methods for characterizing the mechanical behaviour of salt rocks. Triaxial testing is a key tool for determining the strength and deformation characteristics of rocks; however, existing standards often fail to account for the unique features of salts, such as their highly plastic behaviour, creep, temperature sensitivity, and defect-healing capability. The work highlights the critical importance of considering large strains and volumetric changes of specimens during testing, as this enables a more accurate representation of the behaviour of salt rocks, as this enables a more accurate representation of the behaviour of salt rocks. It is proposed that current standards be updated by incorporating well-established correction equations for geometry evolution and volumetric strain, as well as by adopting the Hencky strain measure. Experimental results obtained on natural salt rock specimens and salt-based geomaterials demonstrate significant errors in the evaluation of the stress-strain state when traditional data-processing methods are applied without accounting for the specific properties of salts. The analysis underscores the need to revise existing triaxial testing standards in line with the proposed approaches, thereby improving the accuracy and reproducibility of data that underpin geomechanical modelling and engineering design.

Introduction

For robust constitutive modelling, it is essential to have high-quality and representative input data on the physical and mechanical properties of the materials, as well as their proper interpretation for determining the characteristics of the investigated system. Geomaterials are no exception: understanding the mechanisms governing their deformation behaviour is required across a wide range of stress levels and stress states [1, 2]. Axisymmetric triaxial tests conducted according to the schemes of T. von Kármán and R.Böker form a core experimental method for characterising materials under complex stress-strain conditions [3, 4]. In these methods, a prepared specimen is first subjected to hydrostatic pressure σ1 = σ2 = σ3 in a hydraulic chamber, after which the deviatoric stress is increased to induce triaxial compression or extension by adjusting either the axial load or the confining pressure. The stress states attained in standard test configurations map directly to the Nadai – Lode parameter μσ and the deviatoric Lode angle θ: triaxial compression corresponds to σ1 = σ2 ≠ σ3, μσ = 1, θ = π/6, whereas triaxial extension is characterised by σ1 ≠ σ2 = σ3, μσ = –1, θ = –π/6. The most widely standardised and practically important configuration among these is triaxial compression.

Testing protocols for triaxial compression are generally classified and defined according to the category of natural geomaterials under investigation:

- frozen materials, characterised by cryogenic structural bonding;

- rock materials, in which structural bonds of predominantly chemical nature provide strengths exceeding 5 MPa;

- granular (dispersed) soils, dominated by mechanical, physical and physico-chemical structural bonds;

- semi-rock materials, which exhibit intermediate behaviour between rock and granular soils and are often loose or weakly cemented formations with strengths below 5 MPa.

Salt rocks hold a distinct position among these materials: their strengths may reach and even exceed 40 MPa, yet they exhibit plastic behaviour intrinsically linked to significant creep, which is commonly attributed to the combined action of multiple deformation mechanisms [5]. Among these mechanisms, within the stress and temperature ranges characteristic of most mining and underground construction operations, the following are generally distinguished:

- dislocation creep, driven by defects within grains (crystals) and accompanied by dynamic recrystallisation [6, 7];

- diffusional creep, operating through mass transport in the solid phase [6];

- solution-precipitation creep [6], characterised by dissolution of stressed grain contacts, diffusion of material through thin fluid films, and precipitation on unloaded surfaces [8, 9], as part of a complex and not yet fully understood physico-chemical process [5, 10]. Phenomenologically, it is commonly treated together with diffusional creep;

- damage accumulation, understood as the growth and development of microcracks and pores under deformation, which may progress to the opening of intergranular contacts or the failure of individual grains [7, 11, 12].

Such mechanical behaviour is observed well before the peak strength is reached and, in triaxial tests, is characterised by significant plastic deformation [13, 14] and dilatancy. The associated volumetric expansion under compressive loading persists up to high confining pressures, with its onset conventionally identified by the dilatancy boundary [11]. The underlying creep mechanisms further imply that large strains can develop not only at high stress levels, but also under comparatively low stresses when the loading duration is sufficiently long.

It is essential to account for temperature conditions during testing. The temperature of rocks in situ or under operational conditions may differ substantially from laboratory room temperature. With increasing depth, temperatures within the geological medium rise significantly, and in modern shaft-mining operations in situ rock temperatures may reach 35-60 °С [15-17]. The rocks considered here are highly sensitive to temperature variations [18]. Creep processes are substantially accelerated, and the resulting deformation rates under such conditions may differ by several times compared with those at room temperature [19, 20]. Temperature also affects the immediate mechanical response, influencing both stiffness and strength parameters [21].

It is also important to note another distinctive feature of salt rocks arising from diffusional and solution-precipitation creep [22, 23]: their capacity to restore their structure and heal accumulated defects [20, 24], including those generated during drilling, which can significantly affect test results [25, 26]. This healing capacity can be exploited in the laboratory and is widely recommended as an additional testing stage – a reconsolidation procedure [22, 27], in which the specimen is first preloaded in the triaxial cell under a prescribed, not necessarily isotropic, pressure and held for a certain time until a selected completion criterion is met, after which the standard deviatoric loading stage is carried out. Such reconsolidation stages are commonly carried out under stress and temperature conditions close to those in situ and may continue for extended periods. Some authors limit the procedure to several hours [28], whereas others maintain specimens under load for up to 10 days when testing at deviatoric stress levels above 10 MPa and recommend even longer reconsolidation periods when studying creep at lower stress levels [22]. In some studies, reconsolidation is implemented in several sub-stages [29]. To accelerate these long-lasting processes, elevated mean stresses or temperatures above in situ levels are sometimes applied [30].

Salt rocks differ fundamentally from most conventional hard rocks: even under high confining pressures, their test results cannot reliably be interpreted under the assumptions of small strains and negligible shape change [4]. These assumptions, while often acceptable for hard rocks, can significantly overestimate stress levels in salt specimens and consequently distort assessments of rock-mass behaviour, leading to overly optimistic engineering decisions. This contrast underscores the need for a well-substantiated revision of data-processing and interpretation methods, as well as for the incorporation of dedicated experimental procedures, to ensure that the resulting measurements remain physically representative.

Methods

According to the main widely adopted standards for axisymmetric triaxial compression, such as ASTM, GOST, ISRM recommendations [31, 32], and other national and international guidelines, testing procedures and data processing are generally formulated in terms of engineering (nominal) strain:

where L0, L – the initial and current specimen lengths, respectively.

The only widely used standards that explicitly deviate from this convention are certain ASTM procedures. While they still take the initial specimen geometry as the reference configuration, they permit (but neither require nor explicitly promote as best practice) the consideration of large strains and evolving specimen geometry. This exceptionality arises from their application to triaxial tests at elevated temperatures, where the deformation mechanisms of rocks are further driven from brittle towards plastic regimes. However, even in these cases, the standards do not provide explicit guidance on data processing or on how to account for large deformations and geometry changes in a way that would ensure reproducible implementation across different laboratories.

Thus, in routine laboratory practice the shape of specimens of strong rock is typically assumed to remain constant. In contrast, for granular (dispersed) soils subjected to large strains, various standardisation frameworks have been proposed and widely recommended procedures for correcting the specimens cross-section area [33, 34], either through direct measurements or by introducing an effective cross-sectional area correction of the form:

where А0, А1, А2 – the initial and finite cross-sectional areas of the specimen (under the assumptions of constant and changing volume, respectively); εа – the axial strain; εv – the volumetric strain; b – a coefficient characterising the non-uniform radial deformation of the specimen.

The assumption of small strains and constant specimen geometry for strong rocks is widely adopted for reasons of convenience, since the vast majority of rock types reach their strength limit at very small strains – often with absolute axial strains below 1 % even under high confining pressures; at sufficiently high confinement, many rocks deform plastically and may not reach a distinct failure point at all [4].

However, even strong salt rocks with uniaxial compressive strengths of 40 MPa and higher typically exhibit clearly plastic behaviour already at relatively low confining pressures. In such cases, peak strength may be reached in the range of axial compressive strains from 5 to 30 % [35], or may not be reached at all, with stress–strain curves characterised by continuous hardening [36]. It is therefore evident that such test responses require explicit consideration of large strains.

Outside the community of high-pressure and high-temperature experimentalists, some of the earliest publications to address the treatment of large strains in rock testing were those by German researchers [27]. These studies subsequently formed the basis of recommended testing procedures that emphasise the need to account for “true” strains and strain rates. Nevertheless, they continued to assume constant specimen volume during testing, using a correction function analogous to equation (2) [22, 27]. Similar conclusions were drawn from investigations of salt specimens from the Jiangsu and Jianghan provinces of China [37]. Some authors have further proposed not only expres-sing strain in logarithmic (Hencky) form, but also correcting the specimen geometry according to the following relations [38, 39]:

where ε¯a – the axial Hencky strain; σ¯a – the true axial stress; F – the axial load.

The authors, in line with many previous studies, adopt the Hencky (logarithmic) strain measure for data interpretation:

Where ε¯i – the principal strains; λi – the corresponding principal stretches.

The volumetric strain is then defined as:

In addition, we propose, in the general case, to account for the change in cross-section either from direct radial measurements or from combined axial strain and specimen volume measurements in the pressure chamber, introducing the corresponding corrections under the assumption

and according to

where Amaх, Amean – the maximum and height-averaged cross-sectional areas of the specimen, respectively; A0 и А – the initial and finite cross-sectional areas; λr, λa, λr,e, λa,e – the principal radial and axial stretches and their experimentally obtained values; J – the Jacobian (relative volume change), J = det(F) = λ1 λ2 λ3; ε¯r – the radial strains; ε¯a – the axial strains; ε¯v – the volumetric strain.

Both approaches, for specimens whose shape remains close to an ideal cylinder, yield comparable stress values

or, depending on the apparatus design

where F – the load at the loading piston; ph – the hydrostatic pressure in the chamber; As – the total cross-sectional area of the piston.

Where necessary, additional correction factors should be applied to account for observed non-ideal deformation patterns. The problem of stress correction in specimens of irregular shape has been discussed since the classic studies of the 1940s, and various aspects of it have been examined by many researchers [33, 34, 40], these issues are widely reflected, in different forms, in recommendations for testing granular soils.

Equations (7) are introduced purely for convenience, so that all quantities can be expressed in a single strain measure. When εr, or εa together with εv, are taken from direct measurements, the resulting values, by virtue of relation (6), are fully consistent with the correction function (3), commonly used for soils, as these formulations are equivalent, in contrast to equation (4).

The values likewise coincide with the calculated ones once specimen geometry evolution due to large displacements is taken into account:

where εv, max – the maximum nominal volumetric strain (in the case of specimen “barrelling”) obtained from direct measurements of εa and εr; εr, mean – the average transverse strain over the specimen height derived from direct measurements of εa and εv.

In equation (7) differences between using direct measurements of the radial strain ε¯r and those based on combined axial ε¯a and volumetric measurements ε¯v arise primarily when the final specimen geometry departs from an ideal cylinder. In that case, computing stresses from the fluid-volume change in the pressure cell yields an average cross-sectional area over the specimen height, whereas direct measurements of the cross-section lead to more conservative stress estimates in the presence of specimen “barrelling”. Relative to conventional approaches to interpreting sensor data, the present framework differs in several key respects:

- representation of stress-strain responses in terms of the Hencky strain measure, including the identification of characteristic features such as the onset of dilatancy, peak strength and the attainment of residual strength;

- explicit incorporation of specimen geometry evolution, which is common practice in salt-rock testing internationally but remains only weakly embedded in formal standards;

- explicit incorporation of lateral and volumetric strains, which is largely absent from established rock-testing protocols for rocks in general, including salt.

Typical results from standard triaxial compression tests on salt rocks, conducted in three independent laboratories, are grouped into four groups:

- group 1 – short-term triaxial tests on rock salt with prior reconsolidation of specimens cored from deep boreholes;

- group 2 – short-term triaxial tests on rock salt without prior reconsolidation of specimens cored from deep boreholes;

- group 3 – short-term triaxial tests on an anthropogenic geomaterial, artificially produced as a mixture of salt-processing waste [41] and cements [42-44];

- group 4 – long-term triaxial tests on rock salt and sylvinite without prior reconsolidation.

Presentation of the results is based on comparing the primary experimental curves with those obtained after additional post-processing, evaluated using three approaches:

- approach 1 – strain measure (1) with no stress correction;

- approach 2 – strain measure (5) with stress correction (7) under the assumption ε¯v = 0;

- approach 3 – strain measure (5) with stress correction (7) incorporating the measured volumetric strain ε¯v.

Results

As it is not feasible to display the complete experimental records and their interpretation in graphical form, the raw data (εa, εr, σ1, σ3 for groups 1-3 and t, εa, εr, σ1, σ3 for group 4) are provided in electronic format for full reproducibility and are available at: Supplement: 1 (csv).

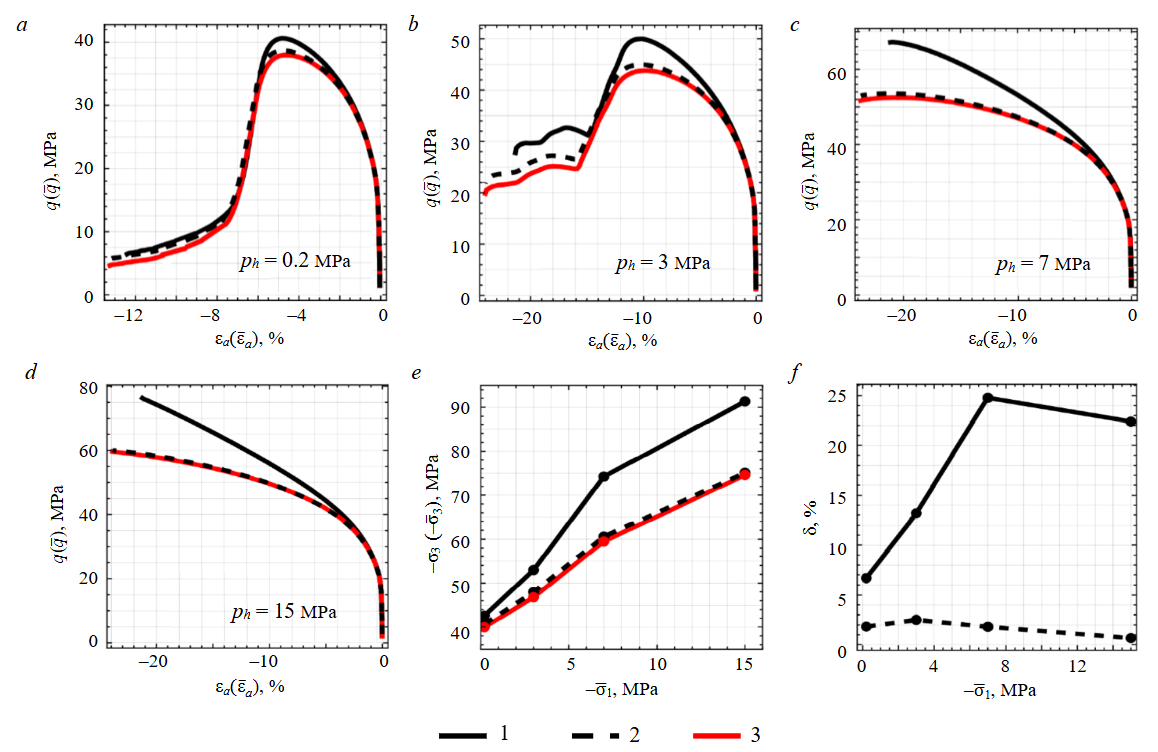

Group 1. Rock-salt specimens recovered from a deep borehole were tested at confining pressures (ph = –σ1 = –σ2) of 0, 2, 3, 7 and 15 MPa. In situ stress magnitudes exceed these confining levels from the deviatoric loading stage. Before the main phase of deviatoric loading, the samples were subjected to reconsolidation [22, 23, 27]. In this series, a brief reconsolidation stage of 2 h was applied at an elevated mean stress of 60 MPa (in situ level – 25 MPa). Volumetric changes in this group were quantified from the axial displacement of the loading piston and the corresponding change in oil volume within the pressure chamber.

The processed results are presented in Fig.1. The relative error was evaluated using the following expression, with the value obtained from approach 3 taken as the reference:

where σ3 – the minimum principal stress determined by the given approach; σ3, ref – the reference minimum principal stress.

All tests exhibited a clear onset of dilatancy at every confining pressure, consistent with the deformation behaviour of such geomaterials [11, 45, 46]. The relative error with respect to the reference method was 24.8 % for approach 1 and 2.5 % for approach 2.

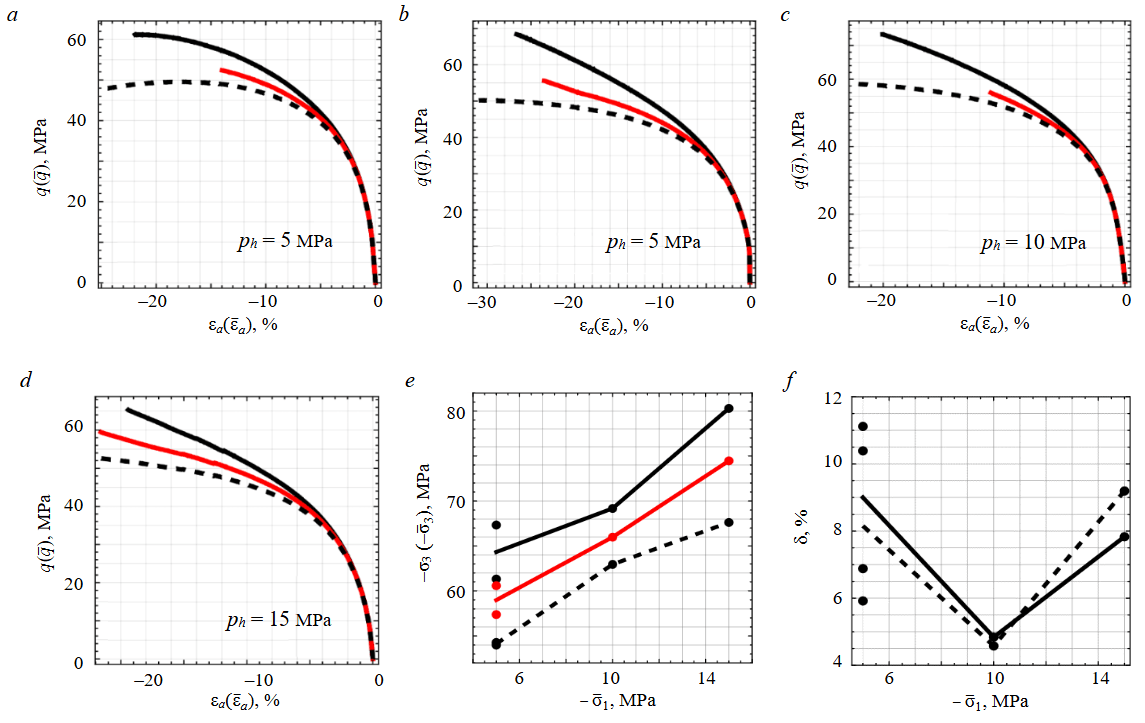

Group 2. Triaxial tests on rock salt specimens recovered from deep boreholes were conducted at confining pressures (ph = –σ1 = –σ2) of 5, 10, and 15 MPa. In situ stresses exceed these confining pressure levels. No reconsolidation stage was performed by the laboratory for this test series. Volumetric strain was inferred from combined axial and circumferential strain measurements obtained using full-bridge strain-gauge systems.

The processed results are presented in Fig.2 in a format analogous to group 1. Even at low confining pressures, specimens in this group exhibited volumetric contraction throughout the entire deformation history, a response that is atypical for rock salt but was consistently observed across a large number of tests. In such cases, accounting for the measured volumetric strain ε¯v leads to less conservative stress estimates than applying a correction under the assumption ε¯v = 0. This behaviour is most likely attributable to technological disturbance of the specimens.

During testing, lateral strain gauges occasionally failed (debonded), and changes in the volume of fluid in the pressure vessel were not recorded, which prevents stress correction over the full strain range. Consequently, the relative error values and the curve shown in Fig.2, d are reported only up to the point immediately preceding gauge failure and should be regarded as substantially underestimated.

Fig.1. Processed results of triaxial tests from group 1: stress-strain curves for different confining pressures (a-d); strength plots in principal stresses (e), and relative error of the approaches (f)

1 – approach 1 (original curve); 2 – approach 2 (correction with ε¯v=0); 3 – approach 3 (with ε¯v≠0)

Fig.2. Processed results of triaxial tests from group 2: stress-strain curves for different confining pressures (a-d); strength plots in principal stresses (e), and relative error of the approaches (f)

For legend, see Fig.1

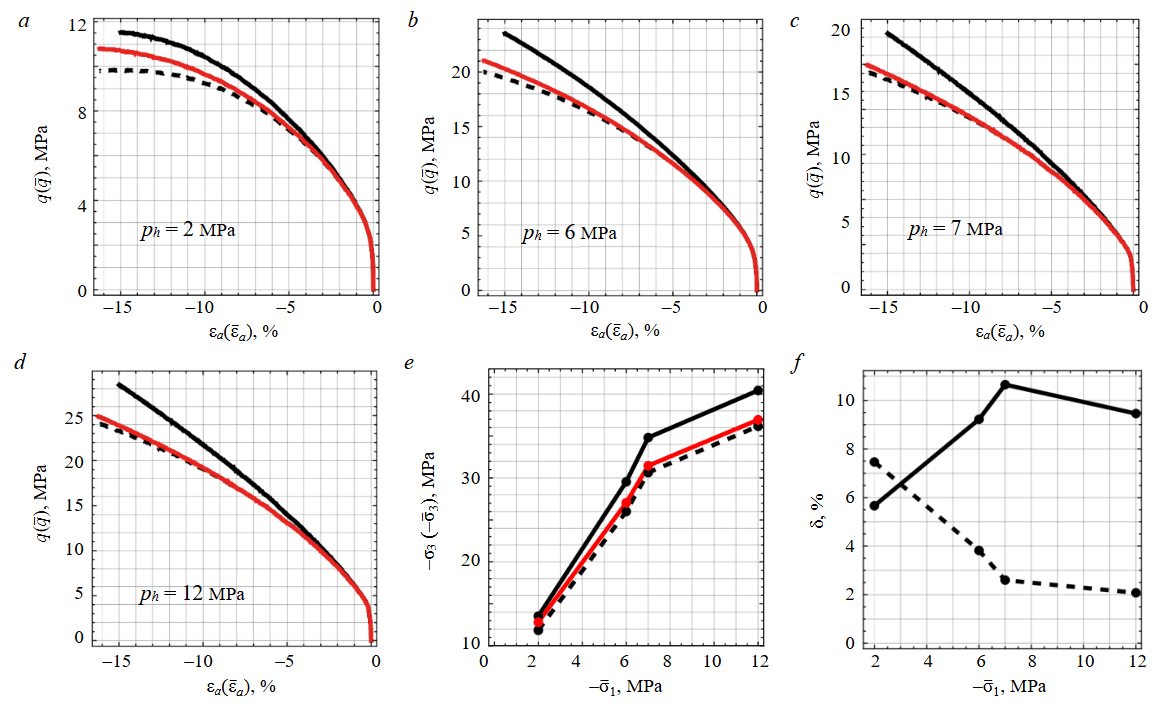

Group 3. Tests were conducted on an artificial geomaterial consisting of a moulded mixture of salt-production waste with a small proportion of cement and chemical admixtures, cured for 28 days. Specimens were loaded at confining pressures (ph = –σ1 = –σ2) of 2, 6, 7, and 12 MPa. Volumetric changes were determined using full-bridge strain-gauge systems recording axial and circumferential strains, supported by measurements of the oil volume in the pressure vessel.

Because the specimens had not been subjected to any prior loading, they exhibited transient volumetric creep during the application of hydrostatic confinement. To minimise the influence of this effect, the specimens were stabilised by consolidating them for 15 min at the target confining pressure before the start of deviatoric loading. As the specimens in this group comprised various mixtures with differing mechanical responses, the data are summarised, which aligns with the objectives of this work.

The processed data are shown in Fig.3 in a format analogous to group 1. The strain ranges observed are comparable to those reported for other salt-bearing artificial materials [47] and may be regarded as an idealised representation of the mechanical response of natural composite rock masses consisting of a strong, brittle framework with a high content of salt-rock inclusions.

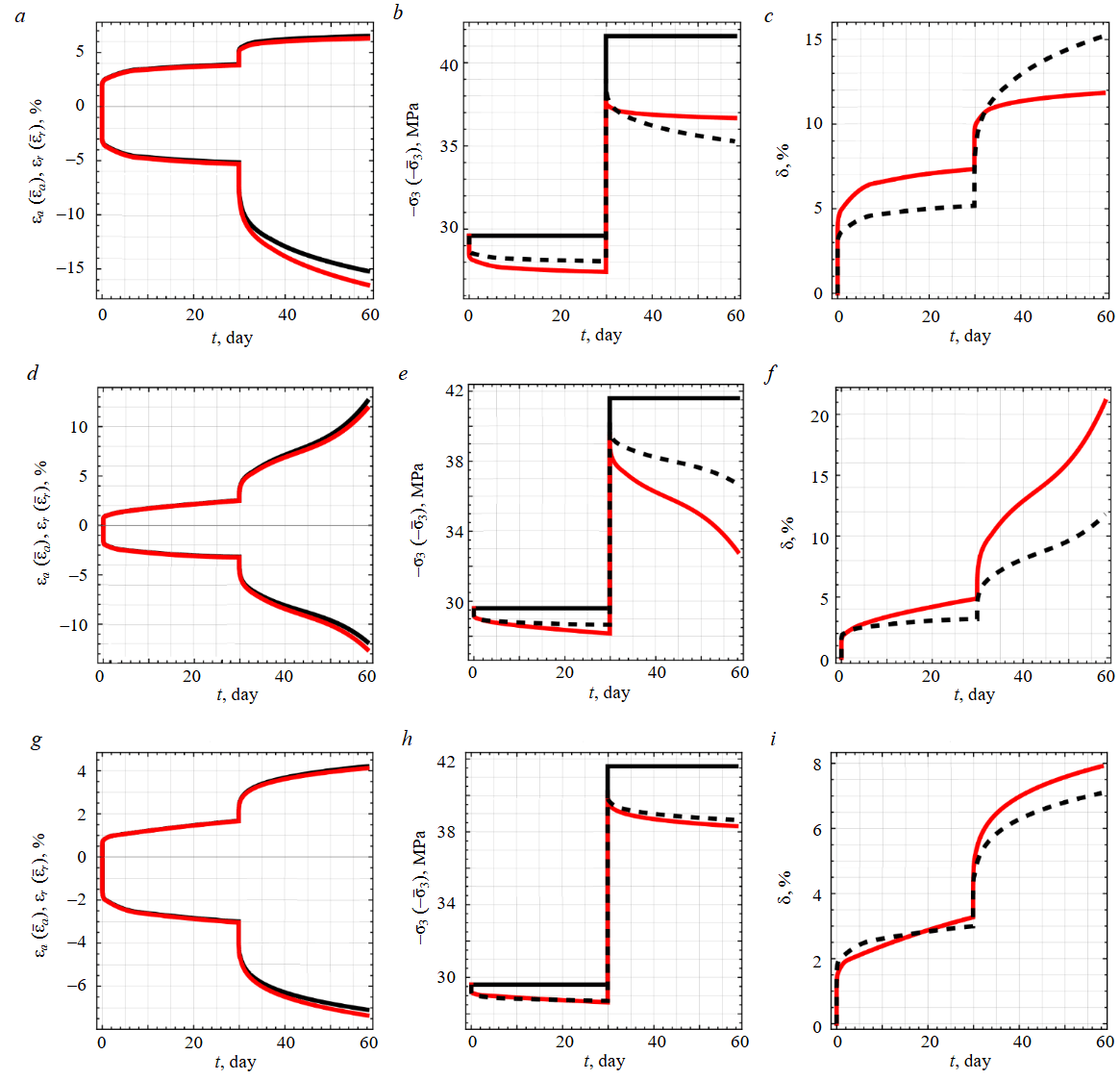

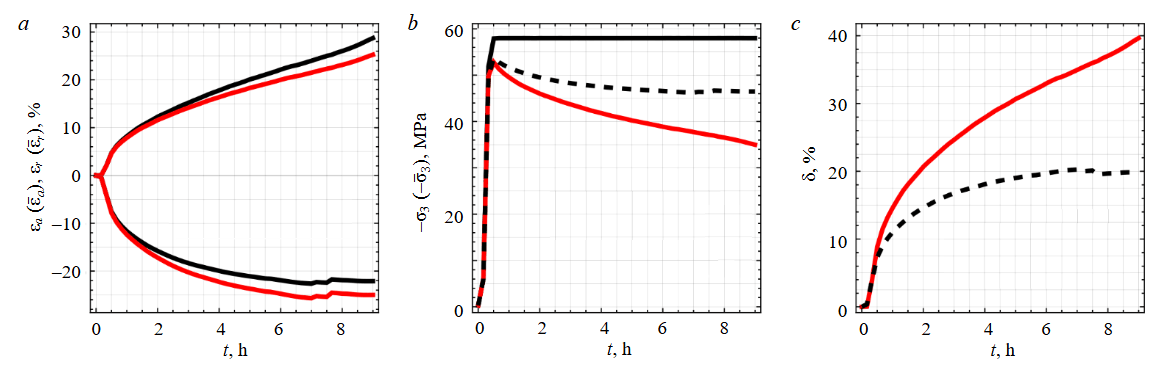

Group 4. Long-term triaxial tests on salt-rock specimens were conducted at confining pressures (ph = –σ1 = –σ2) of 2 MPa for rock salt and 6 MPa for sylvinite. No additional reconsolidation stage was applied. Volumetric changes were evaluated from axial and circumferential strain measurements obtained using full-bridge strain-gauge systems.

The processed results are presented in Fig.4 for rock salt and Fig.5 for sylvinite. Relative error was assessed for the actual axial stresses, with approach 1 taken as the reference because it corresponds to the target stress level (the test configuration prescribed a nominally constant stress). Accordingly, the curves in Fig.4, c, f, i and Fig.5, c should be interpreted as the relative loss of the minimum principal stress σ3 with respect to the prescribed target level, arising from the absence of stress correction during the tests.

Fig.3. Processed results of triaxial tests from group 3: stress-strain curves for different confining pressures (a-d); strength plots in principal stresses (e), and relative error of the approaches (f)

For legend, see Fig.1

Fig.4. Results of the processed triaxial tests for group 5 (rock salt): stress-strain curves (a, d, g), the corresponding actual axial stresses (b, e, h), and relative stress losses (c, f, i) at ph = 2 MPa

For legend, see Fig.1

Fig.5. Results of triaxial tests for group 5 (sylvinite): stress-strain curves (a), the corresponding actual axial stresses (b), and relative stress losses (c) at ph = 6 MPa

For legend, see Fig.1Discussion

Authors’ perspective is based on the following points:

- Triaxial testing of salt rocks performed strictly in accordance with conventional standards, without appropriate modifications or justified deviations, may yield non-physical values in test reports. Reliance on such results without regard to salt-specific behaviour may introduce substantial risks in engineering projects.

- The absence of standardised guidance for such deviations and additions increases inter-laboratory variability, in extreme cases making the results mutually incomparable.

- During the characterisation of the mechanical behaviour of salt rocks, specimen geometry evolution throughout deformation must be taken into account. In international practice, the most common approach is to apply a correction based on the assumption of constant specimen volume. However, neglecting volumetric strains can introduce substantial errors and therefore cannot be justified in all cases.

- Correction equations should incorporate established coefficients to account for non-ideal finite specimen geometries, such as barrelling of the entire sample or of local segments.

- The atypical contraction observed in group 2 specimens is attributed to anthropogenic defects and decompaction relative to their natural in situ state. Because salt rocks are, to some extent, capable of healing such damage, design standards should provide guidance on implementing a reconsolidation stage and on the criteria for its termination. Developing such guidance will require further experimental and theoretical investigations.

- Since triaxial testing of salt rocks often involves strains of 20-30 % [48], the use of the Hencky strain measure in test reporting can somewhat streamline the analysis and interpretation of the results, as well as their subsequent use in numerical modelling [49-51]. If standards retain nominal strain only (1), the effects of specimen geometry evolution at large strains, as captured by equations (1), (8) and (9), must be explicitly accounted for. We therefore recommend that standards permit reporting in a strain measure chosen at the discretion of the end user, provided that the adopted definition is clearly specified in the test documentation.

- Temperatures of salt formations in natural state and during operation may differ substantially from laboratory temperatures, with potentially significant effects on test outcomes, especially in long-term tests. The test temperature should therefore be systematically documented in the test report and, where appropriate, explicitly specified in the laboratory testing programme. Given the importance of this factor and the ongoing trend towards ever greater depths of underground mining operations, there is a clear need for further studies aimed at its quantitative characteristics.

- For salt rocks, test results should include parameters describing deformability in addition to strength. This requirement is dictated by modern engineering needs for advanced constitutive models. Moreover, failure is not always attained within a physically meaningful strain range, which does not diminish the value of the test.

- Updated triaxial compression standards should specify methods for determining not only short-term strength and deformability, but also provide methodological requirements for long-term tests.

- Standardization of testing methods continues to advance [52, 53]. However, the existing international GOST standard for triaxial compression of the “Rocks” series no longer reflects established engineering practice. The national GOST standard in the “Soils” series, despite substantial improvements, still omits several features relevant to salt and salt-bearing rocks. Given the widespread occurrence of such formations, these provisions should be incorporated into the revised triaxial compression standard and adopted at the international level.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates the critical need for revising current testing standards for salt, salt-bearing rocks, and geomaterials with similar mechanical behaviour. Analysis of representative laboratory datasets reveals substantial deficiencies in existing standard triaxial testing protocols. Traditional procedures systematically overlook specimen geometry evolution, large plastic strains, volumetric changes, in situ temperature conditions, and the capacity of such materials to heal induced defects, leading to significant errors in derived mechanical parameters. Reinterpretation and comparison of experimental results show quantitatively large relative errors, underscoring the necessity of implementing improved methodologies to obtain accurate and reproducible data.

Access to data

The experimental results (raw εa, εr, σ1, σ3 data for groups 1-3, and t, εa, εr, σ1, σ3 for group 4) required are available for interpretation and reproduction at the following link: Supplement: 1 (csv).

References

- Karev V.I., Khimulia V.V., Shevtsov N.I. Experimental Studies of the Deformation, Destruction and Filtration in Rocks: A Review. Mechanics of Solids. 2021. Vol. 56. N 5, p. 613-630. DOI: 10.3103/S0025654421050125

- Hunsche U., Albrecht H. Results of true triaxial strength tests on rock salt. Engineering Fracture Mechanics. 1990. Vol. 35. Iss. 4-5, p. 867-877. DOI: 10.1016/0013-7944(90)90171-C

- Ilyinov M.D., Petrov D.N., Karmanskiy D.A., Selikhov A.A. Physical simulation aspects of structural changes in rock samples under thermobaric conditions at great depths. Mining Science and Technology. 2023. Vol. 8. N 4, p. 290-302. DOI: 10.17073/2500-0632-2023-09-150

- Stavrogin A.N., Tarasov B.G. Experimental physics and mechanics of rocks. Saint Petersburg: Nauka, 2001, p. 343 (in Russian).

- Shi-Yuan Li, Urai J.L. Rheology of rock salt for salt tectonics modeling. Petroleum Science. 2016. Vol. 13. Iss. 4, p. 712-724. DOI: 10.1007/s12182-016-0121-6

- Konstantinova S.A., Aptukov V.N. Selected problems in the mechanics of deformation and failure of salt rocks. Novosibirsk: Nauka, 2013, p. 191 (in Russian).

- Zilbershmidt V.G., Zilbershmidt V.V., Naimark O.B. Failure of salt rocks. Moscow: Nauka, 1992, p. 142 (in Russian).

- Schléder Z., Burliga S., Urai J.L. Dynamic and static recrystallization-related microstructures in halite samples from the Klodawa salt wall (central Poland) as revealed by gamma-irradiation. Neues Jahrbuch für Mineralogie. 2007. Vol. 184. Iss. 1, p. 17-28. DOI: 10.1127/0077-7757/2007/0079

- Urai J.L., Spiers C.J. The effect of grain boundary water on deformation mechanisms and rheology of rocksalt during long-term deformation. The Mechanical Behavior of Salt – Understanding of THMC Processes in Salt. CRC Press, 2007, p. 149-158. DOI: 10.1201/9781315106502

- Skvortsova Z.N. Recrystallization Creep As a Form of Adsorption Plastification. Protection of Metals and Physical Chemistry of Surfaces. 2013. Vol. 49. N 5, p. 510-516. DOI: 10.1134/S2070205113050080

- van Oosterhout B.G.A., Hangx S.J.T, Spiers C.J. Mechanisms of dilatancy in rock salt at the grain-scale and implications for the dilatancy boundary. The Mechanical Behavior of Salt X. CRC Press, 2022, p. 25-37. DOI: 10.1201/9781003295808-03

- Vandeginste V., Yukun Ji, Buysschaert F., Anoyatis G. Mineralogy, microstructures and geomechanics of rock salt for underground gas storage. Deep Underground Science and Engineering. 2023. Vol. 2. Iss. 2, p. 129-147. DOI: 10.1002/dug2.12039

- Fan Yang, Jinyang Fan, Zhenyu Yang et al. Plasticity analysis and constitutive model of salt rock under different loading speeds. Journal of Energy Storage. 2023. Vol. 67. N 107583. DOI: 10.1016/j.est.2023.107583

- Lu Wang, Jianfeng Liu, Huining Xu, Yangmengdi Xu. Research on Confining Pressure Effect on Mesoscopic Damage of Rock Salt Based on CT Scanning. Proceedings of GeoShanghai 2018 International Conference: Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering. Springer, 2018, p. 254-262. DOI: 10.1007/978-981-13-0113-1_28

- Holländer R., Schröter U.-C., Wilke F.H. Experiences with slim Solution Mining Caverns for ventilation purposes in a potash mine. Kali und Steinsalz. Verband der Kali- und Salzindustrie, 2012. Iss. 1, p. 32-37.

- Woods P.J.E. The geology of Boulby Mine. Economic Geology. 1979. Vol. 74. N 2, p. 409-418. DOI: 10.2113/gsecongeo.74.2.409

- Baryakh А.А., Smirnov E.V., Kvitkin S.Y., Tenison L.O. Russian potash industry: Issues of rational and safe mining. Russian Mining Industry. 2022. N 1, p. 41-50 (in Russian). DOI: 10.30686/1609-9192-2022-1-41-50

- Kravcenko O.S., Filimonov Yu.L. Deformation of rock salt under increased temperature. Mining Informational and Analytical Bulletin. 2019. N 1, p. 69-76 (in Russian). DOI: 10.25018/0236-1493-2019-01-0-69-76

- Shkuratnik V.L., Kravchenko O.S., Filimonov Yu.L. Stresses and Temperature Affecting Acoustic Emission and Rheological Characteristics of Rock Salt. Journal of Mining Science. 2019. Vol. 55. N 4, p. 531-537. DOI: 10.1134/S1062739119045879

- Salzer K., Günther R.-M., Minkley W. et al. Joint project III on the comparison of constitutive models for the mechanical behavior of rock salt II. Extensive laboratory test program with clean salt from WIPP. Mechanical Behaviour of Salt VIII. CRC Press, 2015, p. 3-12. DOI: 10.1201/b18393

- Sriapai T., Walsri C., Fuenkajorn K. Effect of temperature on compressive and tensile strengths of salt. ScienceAsia. 2012. Vol. 38, p. 166-174. DOI: 10.2306/scienceasia1513-1874.2012.38.166

- Günther R.-M., Salzer K., Popp T., Lüdeling C. Steady-State Creep of Rock Salt: Improved Approaches for Lab Determination and Modelling. Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering. 2015. Vol. 48. Iss. 6, p. 2603-2613. DOI: 10.1007/s00603-015-0839-2

- Hansen F., Popp T., Wieczorek K., Stührenberg D. Salt reconsolidation applied to repository seals. Mechanical Behaviour of Salt VIII. CRC Press, 2015, p. 179-189. DOI: 10.1201/b18393

- Fuenkajorn K., Phueakphum D. Laboratory assessment of healing of fractures in rock salt. Bulletin of Engineering Geology and the Environment. 2011. Vol. 70. Iss. 4, p. 665-672. DOI: 10.1007/s10064-011-0370-y

- Ilyinov M.D., Kartashov Yu.M., Karmansky A.T., Kozlov V.A. Influence of rock disturbance on their rheological properties. Journal of Mining Institute. 2010. Vol. 185, p. 31-36 (in Russian).

- Aptukov V.N., Volegov S.V. Modeling Concentration of Residual Stresses and Damages in Salt Rock Cores. Journal of Mining Science. 2020. Vol. 56. N 3, p. 331-338. DOI: 10.1134/S1062739120036806

- Hunsche U. Uniaxial and Triaxial Creep and Failure Tests on Rock: Experimental Technique and Interpretation. Visco-Plastic Behaviour of Geomaterials. Springer, 1994, p. 1-53. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-7091-2710-0_1

- Tavostin M.N., Koshelev A.E., Osipov Yu.V. Study of physico-mechanical properties of rock salt with the tentative comprehensive loading. Mining Informational and Analytical Bulletin. 2015. N 2, p. 89-96 (in Russian).

- Wolters R., Sun-Kurczinski J.Q., Düsterloh U. et al. WEIMOS: Laboratory investigation and numerical simulation of damage reduction in rock salt. The Mechanical Behavior of Salt X. CRC Press, 2022, p. 190-199. DOI: 10.1201/9781003295808-18

- Lüdeling C., Günther R.-M., Hampel A. et al. WEIMOS: Creep of rock salt at low deviatoric stresses. The Mechanical Behavior of Salt X. CRC Press, 2022, p. 130-140. DOI: 10.1201/9781003295808-13

- Suggested methods for determining the strength of rock materials in triaxial compression: Revised version. International Journal of Rock Mechanics and Mining Sciences & Geomechanics Abstracts. 1983. Vol. 20. Iss. 6, p. 285-290. DOI: 10.1016/0148-9062(83)90598-3

- Aydan Ö., Ito T., Özbay U. et al. ISRM Suggested Methods for Determining the Creep Characteristics of Rock. Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering. 2014. Vol. 47. Iss. 1, p. 275-290. DOI: 10.1007/s00603-013-0520-6

- La Rochelle P., Leroueil S., Trak B. et al. Observational Approach to Membrane and Area Corrections in Triaxial Tests. Advanced Triaxial Testing of Soil and Rock. ASTM International, 1988, p. 715-731. DOI: 10.1520/STP29110S

- Lade P.V. Triaxial Testing of Soils. Wiley-Blackwell, 2016, p. 432. DOI: 10.1002/9781119106616

- Pankov I.L., Morozov I.A. Salt Rock Deformation under Bulk Multiple-Stage Loading. Journal of Mining Institute. 2019. Vol. 239, p. 510-519. DOI: 10.31897/PMI.2019.5.510

- Asanov V.A., Baryakh A.A., Zhigalkin V.M. et al. Laboratory study of saline rock deformation. Physical Mesomechanics Journal. 2008. Vol. 11. N 1, p. 14-18 (in Russian).

- Guan Wang, Wei Xing, Jianfeng Liu, Lingzhi Xie. Comparison of Triaxial Compression Short-Term Strength Tests and Data Processing Methods for Rock Salt. Clean Energy Systems in the Subsurface: Production, Storage and Conversion. Springer, 2013, p. 305-315. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-642-37849-2_25

- Renbo Gao, Fei Wu, Jie Chen et al. Accurate characterization of triaxial deformation and strength properties of salt rock based on logarithmic strain. Journal of Energy Storage. 2022. Vol. 51. N 104484. DOI: 10.1016/j.est.2022.104484

- Yu Bian, Jianfeng Liu, Guosheng Ding et al. Different Methods to Evaluate Strength from Compression Tests for Rock Salt. Clean Energy Systems in the Subsurface: Production, Storage and Conversion. Springer, 2013, p. 281-291. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-642-37849-2_23

- Rouabhi A., Labaune P., Tijani M. et al. Phenomenological behavior of rock salt: On the influence of laboratory conditions on the dilatancy onset. Journal of Rock Mechanics and Geotechnical Engineering. 2019. Vol. 11. Iss. 4, p. 723-738. DOI: 10.1016/j.jrmge.2018.12.011

- Karasev M.A., Selikhov A.A., Bychin A.K. Laboratory tests and analysis of mathematical models of deformation of crushed salt rocks. News of the Ural State Mining University. 2023. Iss. 4 (72), p. 94-105 (in Russian). DOI: 10.21440/2307-2091-2023-4-94-105

- Hinze M., Sinan Xiao, Schmidt A., Nowak W. Experimental evaluation and uncertainty quantification for a fractional viscoelastic model of salt concrete. Mechanics of Time-Dependent Materials. 2023. Vol. 27. Iss. 1, p. 139-162. DOI: 10.1007/s11043-021-09534-9

- Sturm P., Moye J., Gluth G.J.G. et al. Properties of alkali-activated mortars with salt aggregate for sealing structures in evaporite rock. Open Ceramics. 2021. Vol. 5. N 100041. DOI: 10.1016/j.oceram.2020.100041

- Jantschik K., Czaikowski O., Moog H.C., Wieczorek K. Investigating the sealing capacity of a seal system in rock salt (DOPAS project). Kerntechnik. 2016. Vol. 81. Iss. 5, p. 571-585. DOI: 10.3139/124.110721

- Baryakh A.A., Konstantinova S.A., Asanov V.A. Deformation of salt rocks. Yekaterinburg: UrO RAN, 1996, p. 204 (in Russian).

- Khloptsov V.G., Semenova M.V., Khloptsov D.V. Mechanical properties of rock salt. Moscow; Izhevsk: Institut kompyuternykh issledovanii, 2022, p. 104 (in Russian).

- Karasev M.A., Selikhov A.A., Bychin A.K. Laboratory study of the backfilling material based on halite waste. Transport, mining and construction engineering: science and production. 2023. N 23, p. 180-188 (in Russian). DOI: 10.26160/2658-3305-2023-23-180-188

- Osipov Yu.V., Voznesensky A.S. Determination of Rheological Properties of Bischofite from Triaxial Tests. Journal of Mining Science. 2022. Vol. 58. N 6, p. 886-895. DOI: 10.1134/S1062739122060023

- Kazlouski Ja.Ja., Zhuravkov M.A. Investigation of the stress-strain state of various types of mine shaft linings in carnallite rock mass. Mechanics of Machines, Mechanisms and Materials. 2023. N 2 (63), p. 53-60 (in Russian). DOI: 10.46864/1995-0470-2023-2-63-53-60

- Aptukov V.N., Volegov S.V. Simulation of the process of deformation and fracture of saliferous rock samples under compression. Bulletin of Perm University. Mathemathics. Mechanics. Computer Science. 2017. Iss. 3 (38), p. 49-54 (in Russian). DOI: 10.17072/1993-0550-2017-3-49-54

- Karasev M.A., Protosenya A.G., Katerov A.M., Petrushin V.V. Analysis of shaft lining stress state in anhydrite-rock salt transition zone. Rudarsko-geološko-naftni zbornik. 2022. Vol. 37. N 1, p. 151-162. DOI: 10.17794/rgn.2022.1.13

- Trufanov A.N., Rostovtsev A.V. Current changes in the field of interstate and national standards for determining the mechanical characteristics of soils. Mezhdunarodnyi stroitelnyi kongress. Nauka. Innovatsii. Tseli. Stroitel'stvo: Sbornik tezisov dokladov. Moscow: NITs “Stroitelstvo”, 2023, p. 118-119 (in Russian). DOI: 10.37538/2949-219Х-2023-118-119

- Ilinov M.D., Korshunov V.A., Pospekhov G.B., Shokov A.N. Integrated experimental research of mechanical properties of rocks: Problems and solutions. Gornyi zhurnal. 2023. N 5, p. 11-18 (in Russian). DOI: 10.17580/gzh.2023.05.02