Diamond polygenicity from Carnian deposits of the Bulkur anticline of the northeast Siberian platform

- 1 — Ph.D. Senior Researcher V.S.Sobolev Institute of Geology and Mineralogy SB RAS ▪ Orcid

- 2 — Ph.D. Senior Researcher Diamond and Precious Metal Geology Institute of Siberian Branch of RAS ▪ Orcid

- 3 — Ph.D. Chief Geologist ALROSA (Zimbabwe) Limited ▪ Orcid

- 4 — Junior Researcher V.S.Sobolev Institute of Geology and Mineralogy SB RAS ▪ Orcid

- 5 — Ph.D., Dr.Sci. Chief Researcher V.S.Sobolev Institute of Geology and Mineralogy SB RAS ▪ Orcid

Abstract

A comprehensive study of the Carnian diamonds of the Bulkur anticline in the northeastern Siberian craton has been conducted. Two most common diamond types in the Bulkur area have been identified: scarred dodecahedroids and crystals of varieties V-VII according to the Yu.L.Orlov classification. These groups are characterized by a lighter carbon δ13C isotope composition from –19.6 to –24.7 ‰, differing in morphology, concentration and forms of nitrogen aggregation, and composition of melt inclusions. Submicroscopic inclusions in diamonds of these groups have been studied for the first time. Such inclusions in dodecahedroids are of less ferruginosity (12 and 31 wt.% FeO on average) and more enriched in potassium (5.5 and 1.7 wt.% K2O on average) compared to diamonds of varieties V-VII. It is concluded that the studied dodecahedroids with scars from the Carnian deposits of the Bulkur anticline represent a separate type of diamonds characteristic to the northeast of the Siberian platform. It is assumed that the primary sources are Precambrian in age and that the diamonds entered the Triassic and younger placers as a result of the erosion of Proterozoic coastal-marine deposits within the Precambrian protrusions, in particular on the Olenek uplift.

Funding

Work is done on State assignment of IGM SB RAS N 122041400157-9 and DPMGI SB RAS FUFG-2024-0007.

Introduction

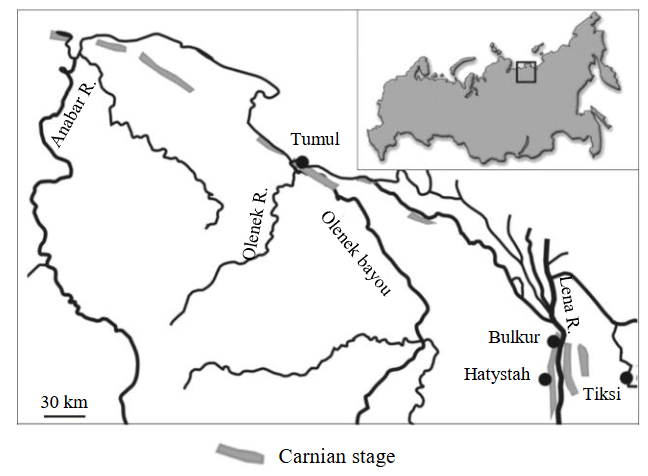

The diamond potential of the Carnian stage deposits of the Upper Triassic age within the Bulkur anticline along the left bank of the Lena River in its lower reaches was discovered in the 1970s and was intensively studied [1] (Fig.1). The diamond potential of the Carnian stage varies laterally. The highest concentrations are found in the lower Lena region, where the placers of the Bulkur anticline are distinguished by very high diamond potential, while their productivity decreases to the west and east of it [2]. The formation is represented by terrigenous rocks with abundant marine fauna, the thickness of the formation varies from 10 to 100 cm. The formation comes out on the day surface with its end and plunges to the west into the Predverkhoyansk trough at an angle of up to 30° or more.

Fig.1. Schematic map of the location of diamond-bearing rocks of the Carnian stage within the northeast of the Siberian craton. The square on the inset – the location of the area.

The scheme is based on the article [19]

The diamond content within the formation fluctuates and reaches 13 ct/m3 [3, 4]. Indicator minerals of kimberlites without signs of mechanical wear and hypergene corrosion are abundant, which indicates the proximity of the primary source [5, 6]. There are small amounts of diamond suite grains among the pyropes [1]. This allowed us to assume the existence of a nearby kimberlite body (bodies) with high diamond content. However, the exploration conditions, primarily the rapid subsidence of the formation in the western direction under the sediments of the Predverkhoyansk trough, did not allow us to discover the primary source of diamonds. Exploration criteria for diamonds based on their satellite minerals are widely used both within the Yakutian diamondiferous province and in other territories promising for diamond content [7, 8].

A large number of diamonds found in the Bulkur anticline were studied in the Amakin expedition of the ALROSA and described in [9, 10]. The unusual nature of the diamond suite was shown, up to 80 % of which have a light carbon isotope composition, and a conclusion was made about the unknown type of primary source. This situation is typical for the Anabar placers (Ebelyakh, Mayat, etc.), where, as in Bulkur, diamonds that are completely atypical for kimberlite bodies are associated with kimberlite minerals. This contradiction was considered by the authors in [11], where the polygenesis of diamonds is argued not only by typomorphism, but also by the types of primary sources. It is assumed that the deposits of the Carnian stage are Late Triassic tuffites and diamond potential is associated with them [12]. However, neither here nor in other places of the Siberian platform have volcanic sources of these tuffs been found. As a result, the situation with the diamond-bearing capacity of the Carnian stage remains unclear.

An additional study of the Carnian diamonds of the Bulkur anticline was undertaken to determine their origin and routes of entry into these deposits. It is important to use an integrated approach to the study of diamond, a mineral with a wide range of physicochemical, morphological and other features that can collectively determine its typomorphism. It is generally accepted that mineral inclusions in natural diamonds, captured by them during growth, reflect the geochemical features of the upper mantle silicate substrate composition [13-16]. However, fundamental genetic information on the composition of the diamond-forming environment can be obtained based on the results of studying submicroscopic and nanosized inclusions captured by diamond at the initial stage of crystallization of the diamond matrix [17, 18].

In order to clarify the features of the crystallization environment and evolutionary changes during the growth of diamonds presented in the Carnian stage deposits, this work is the first to study multiple submicroscopic polyphase inclusions in these diamonds. Such studies are especially necessary for diamonds in which mineral inclusions visible in the optical magnification range are rare. The isotopic composition of carbon in diamonds, the concentration and forms of structural nitrogen impurity were also studied.

Samples and research methods

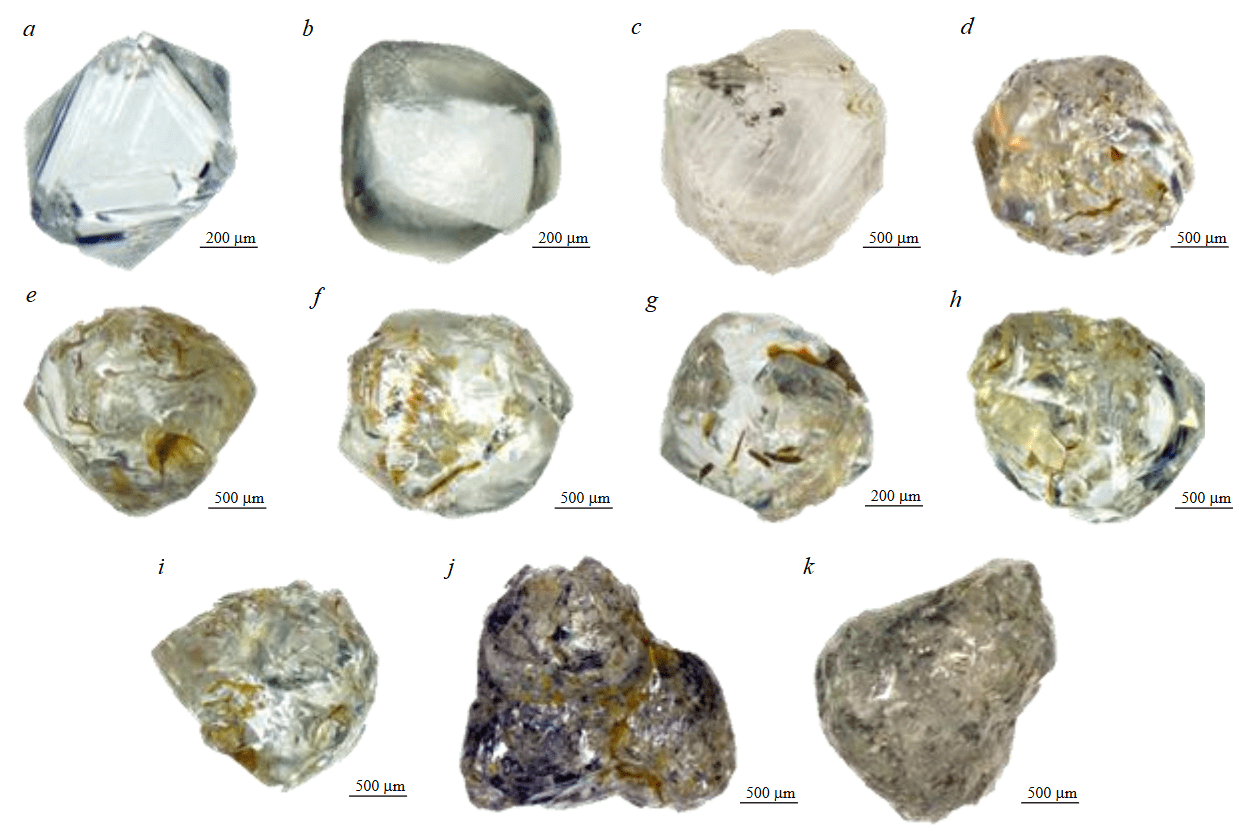

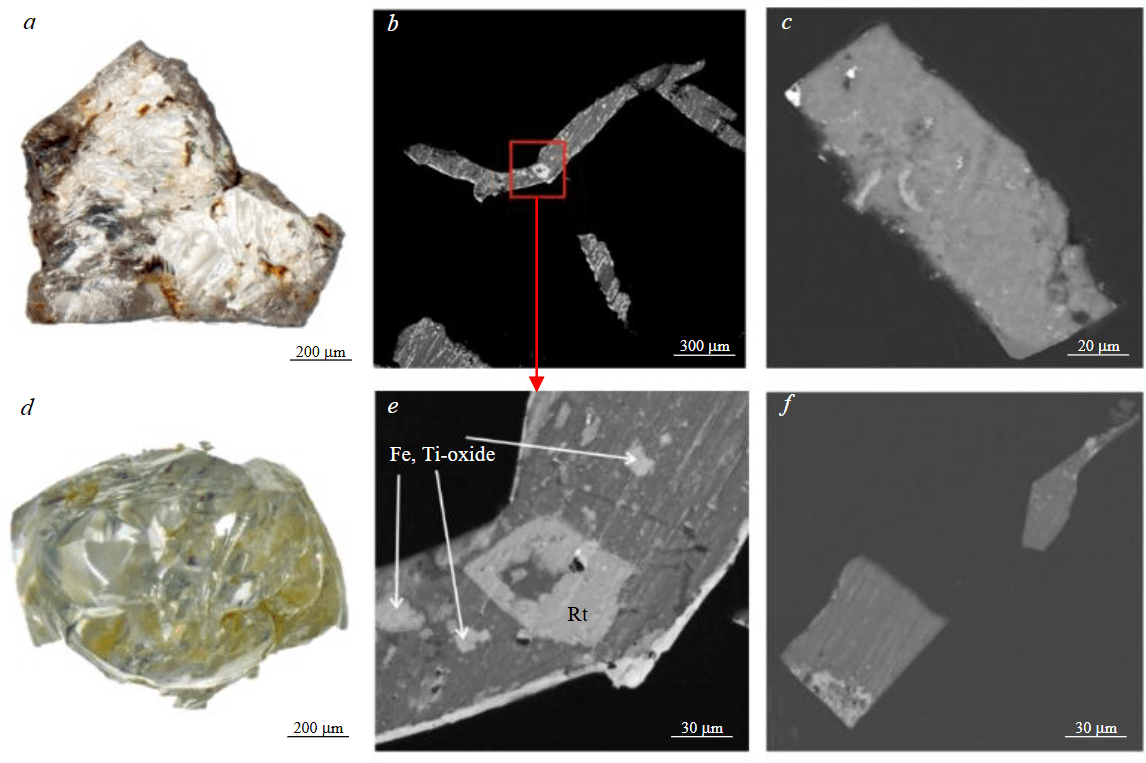

A total of 97 diamond crystals ranging in size from 1 to 4 mm from Carnian deposits of the Bulkur anticline (lower reaches of the Lena River, Bulkur area) were studied (Fig.1). A characteristic morphological feature of the diamonds from this area is the predominance of typical dodecahedroids (51.7 %), often cryptolayered and with sheaf-like striation, less often with shagreen and bands of plastic deformation. On the surface of such crystals, as a rule, there are scars filled with secondary material, which are a sign of magmatic etching. Of the total number of crystals, 35 % are classified as V and VII varieties according to the Yu.L.Orlov classification [20]. Such crystals have a gray to black color due to the pre-sence of numerous fluid inclusions with amorphous carbon on their faces (Fig.2, j, k) [21, 22]. Laminar crystals of octahedral and transitional octahedron – rhombododecahedron habit are rare (about 13 %) (Fig.2, a-c). They are up to 1 mm in size and are represented by sharp-edge octahedrons. Two samples are fragments of yellow cubic habit crystals (II variety according to the classification of Yu.L.Orlov). Such crystals are often found in diamond placers of Yakutia and the Urals [23]. An important characteristic of the studied collection is the high content (more than 50 %) of whole and slightly damaged crystals, but for most of them increased fracturing with products of exogenous ferruginization is noted.

In this work, crystals of the most common types of diamonds in the Bulkur area were selected for detailed studies of microinclusions: dodecahedroids with scars and numerous dark-colored inclusions (Fig.2, d-i), as well as diamonds of V-VII varieties (Fig.2, j, k). The internal structure of the diamonds and the nature of the distribution of structural impurities in them were studied on plane-parallel plates 90-170 μm thick, cut mainly along the (110) plane.

Fig.2. Typical diamond crystals of the studied collection

a-с – diamonds of the variety I according to Yu.L.Orlov: a, c – a colorless octahedron with polycentrically growing edges, b – curved dodecahedron; d-i – curved dodecahedron with deep scars on the surface filled with ironification products; j, k – diamonds of V-VII varieties with numerous dark-colored inclusions

The distribution of nitrogen and hydrogen impurities was determined from the spectra. The spectra with an aperture of 50 μm were recorded in the range of 750-7500 cm–1 at a resolution of 2 cm–1 on a VERTEX 70 FT-IR spectrometer (Bruker) equipped with a HYPERION 2000 microscope. Individual growth zones of the studied diamonds, as well as zones with a predominant location of inclusions, were identified by the cathodoluminescence (CL) method using a LEO-1430VP scanning electron microscope with an energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometer. The isotopic composition of carbon was determined with a Finnigan-MAT Delta mass spectrometer in the double-inlet mode after oxidation of the sample in pure oxygen according to the method [24]. The measurement error of the isotope ratio did not exceed ±0.02 ‰. The isotopic data are given relative to the international standard PDB.

To study mineral inclusions, the crystals were grind in until the inclusion was brought to the surface of the diamond matrix. Identification of some mineral phases was carried out by Raman spectroscopy on a Horiba Jobin-Yvon LabRam HR800 device. The chemical composition of the inclusions was determined using a MIRA 3 scanning microscope (TESCAN, Czech Republic). The phase composition of nanosized polyphase inclusions was studied by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) on a Philips CM200 (LaB6) device at an accelerating voltage of 200 kV [25, 26].

The main part of the analytical work was carried out at the Analytical Center for multi-elemental and isotope research of the Siberian Branch of the RAS. Research using the transmission electron microscopy method was carried out at the GFZ Helmholtz Centre for Geosciences (Potsdam, Germany).

Results and discussion

IR spectroscopy

According to the diamond classification [27, 28], all the studied samples belong to the 1aAB type with impurity nitrogen in the form of A and B1. The IR spectra also show absorption bands with maxima at 1370 and 1430 cm–1, due to the presence of the B2 defect in diamonds [29], and a peak at 3107 cm–1, caused by hydrogen impurity, is often observed [30].

Based on the content and distribution of the structural nitrogen impurity, taking into account the morphology of diamonds, four groups have been identified (Table 1). The first group of diamonds studied can be classified as kimberlite based on the morphology of their crystals, the range of nitrogen content and the degree of its aggregation with a high degree of probability. The second group, represented by a yellow cuboid, corresponds to diamonds of the II variety according to the Yu.L.Orlov classification [20]. The third group includes rounded colorless dodecahedroids with scars filled with secondary products. Diamonds of this group predominate in the placer under consideration. They have a high content of nitrogen impurity with a fairly high degree of aggregation. The fourth group is represented by typical diamonds of the V-VII varieties according to the Yu.L.Orlov classification [20]. The groups differ significantly from each other both in the total content of nitrogen impurity (from 47 to 1956 ppm) and in the degree of its aggregation, which, along with differences in morphology, directly indicates the polygenicity of placer diamonds.

Table 1

Structural impurity composition of the studied diamonds

|

Sample number |

Zone |

N(A), ppm |

N(B), ppm |

Ntot, ppm |

B, % |

Diamond description |

|

Kar-80 |

Center Rim |

64 45 |

7 3 |

71 47 |

10 5 |

Colorless dodecahedron |

|

Kar-19 |

Center Rim Rim Rim |

290 413 503 437 |

185 307 346 272 |

474 720 849 709 |

39 43 41 38 |

Colorless octahedron |

|

Kar-21 |

Center Rim Rim |

287 376 404 |

312 541 523 |

599 917 928 |

52 59 56 |

Colorless dodecahedron |

|

Kar-78 |

Rim Center |

239 302 |

157 235 |

397 536 |

40 44 |

Colorless octahedron |

|

Kar-101 |

Rim Center |

427 396 |

80 94 |

507 490 |

16 19 |

Colorless dodecahedron |

|

Kar-16 |

Rim Center Center |

100 96 106 |

0 0 0 |

100 96 106 |

0 0 0 |

Yellow cuboid |

|

Kar-2 |

Center Rim |

866 776 |

300 429 |

1167 1205 |

26 36 |

Dodecahedron with scars |

|

Kar-15А |

Center Rim Rim |

776 809 766 |

398 389 389 |

1173 1197 1155 |

34 32 34 |

Dodecahedron with scars |

|

Kar-74 |

Rim Rim Center |

771 766 807 |

447 443 355 |

1218 1209 1162 |

37 37 31 |

Dodecahedron with scars |

|

Kar-87 |

Center Rim |

825 833 |

315 315 |

1140 1148 |

28 27 |

Dodecahedron with scars |

|

Kar-88 |

Rim Center |

540 535 |

332 337 |

871 872 |

38 39 |

Dodecahedron with scars |

|

Kar-34 |

Rim Rim Center Center |

1667 1642 1609 1543 |

286 315 329 286 |

1953 1956 1938 1829 |

15 16 17 16 |

The variety V |

|

Kar-38 |

Rim Rim Center |

1328 1345 1180 |

315 372 472 |

1643 1717 1652 |

19 22 29 |

The variety V |

|

Kar-38a |

Rim Rim Center |

1490 1302 1289 |

272 269 409 |

1762 1571 1698 |

15 17 24 |

The variety V |

Defects in the crystal structure of diamonds are an indicator of crystallogenesis [31]. In the article [32], the defect-impurity composition of diamonds from the Bulkur anticline was studied, where all the described dodecahedroids were classified as variety I according to the classification of Yu.L.Orlov [20].

Inclusions in diamonds

Mineral and melt inclusions in dodecahedral diamonds with scars and in diamonds of the V variety, which we identified in the Carnian stage deposits, were studied. Visually, they are represented mainly by graphite, sulfides or dark-colored material. As a rule, such inclusions reflect the composition of the diamond-forming substrate [33].

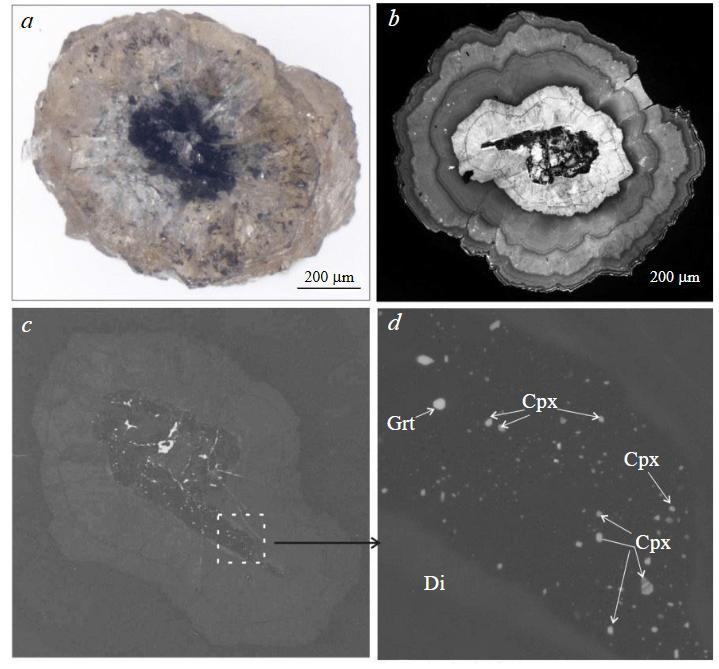

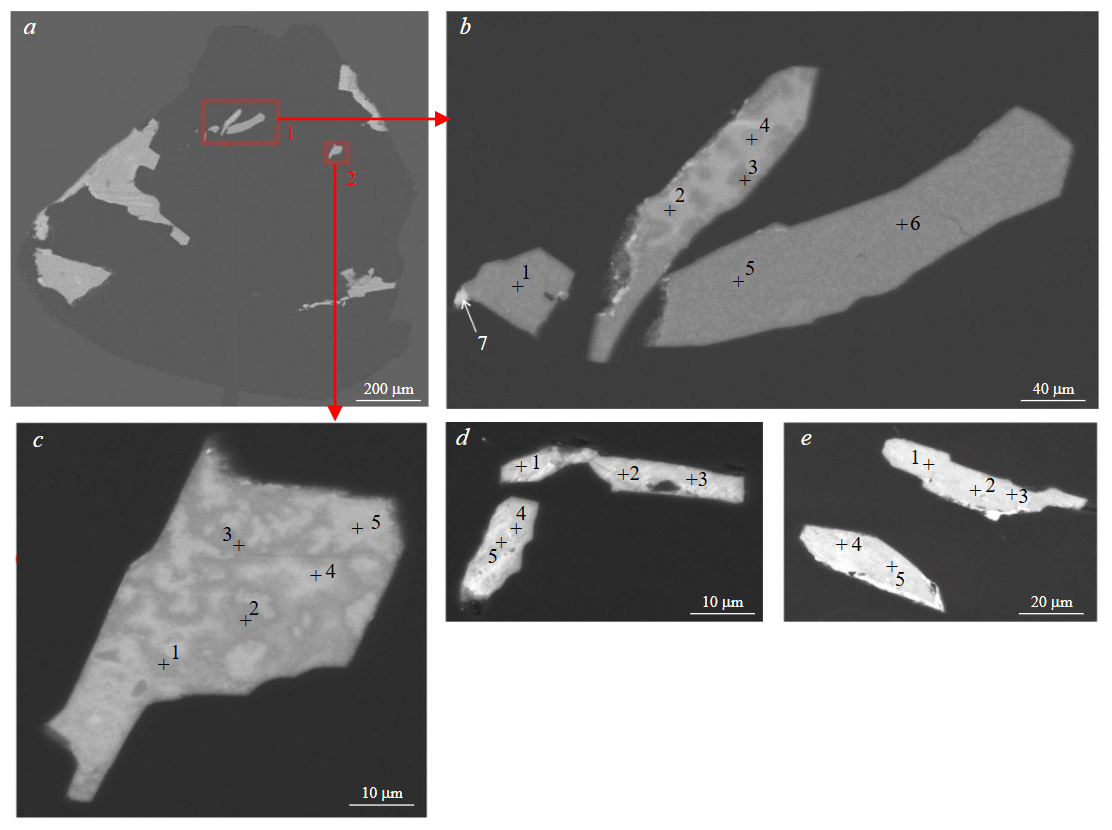

Dodecahedroids with scars. In the central growth zone of the dodecahedral crystal of diamond Kar-15, multiple silicate inclusions of monoclinic pyroxene and garnet (Fig.3, a, b) in association with nanosized polyphase crystal-fluid inclusions were recorded. These inclusions have extremely small sizes, not exceeding 5 µm, a rounded shape, sometimes crystallographic faceting is manifested. According to the chemical composition, they are represented by monoclinic pyroxene, garnet, mica and polyphase formations. They are partially altered, as evidenced by the presence of chlorite and other undiagnosed phases (Table 2). The chemical composition of garnets and pyroxenes varies within insignificant limits. The inclusions of almandine-pyrope garnet belong to the lherzolite paragenesis and are characterized by a low content, wt.%: Cr2O3 1.5, a typical amount of CaO for this association of about 4.43, FeO 15.5 and MgO 14.9 [10]. According to the chemical composition, the pyroxenes are divided into two groups based on the Na2O content. The first group includes pyroxenes characterized by a relatively high content of the jadeite end member Na2O 3.6-4.8 wt.%, an increased content of FeO and a stable admixture of Cr2O3 about 1 wt.% (Table 2). In the second group of pyroxenes, the Na2O content does not exceed 1 wt.%. Ilmenite was identified in association with garnet and clinopyroxene, wt.%: TiO2 49.1; FeO 42.1; Cr2O3 0.98; MnO 4.89; MgO 2.87 and mica with barium impurity BaO 3.0-4.1. This is the first finding of mica in a diamond with a high barium content. The stable presence of barium in the diamond-forming environment is confirmed by the composition of the polyphase nanosized inclusions recorded in the central part of this diamond sample and studied by the TEM method (Fig.3).

Fig.3. General view (a) of a polished diamond crystal Kar-15 (Bulkur area, lower reaches of the Lena River); cathodoluminescent image (b); BSE image of the crystal centre (c); the area of inclusions location (c) in enlarged fragment (d);

Cpx – clinopyroxene; Grt – garnet; Di – diamond

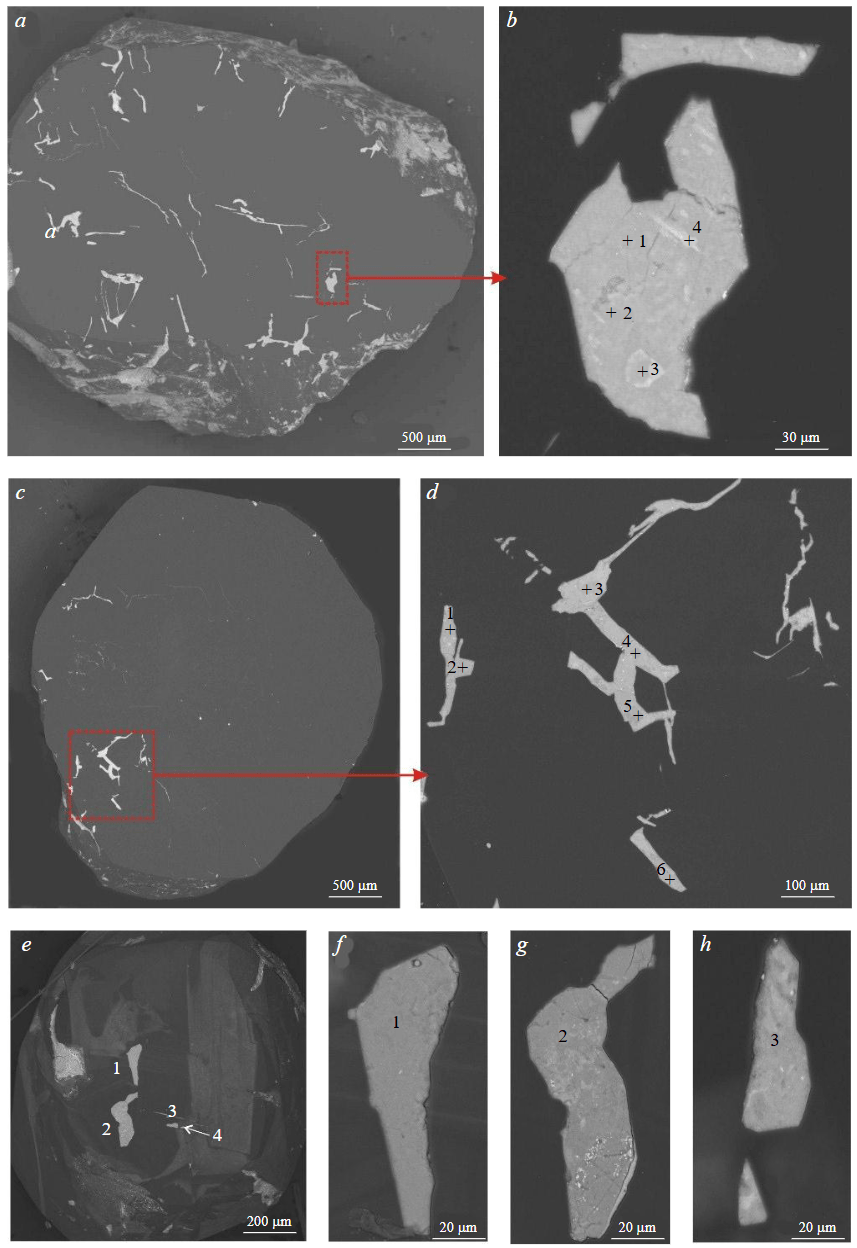

In nine samples of scarred dodecahedroids, the chemical composition of the dark-colored substance (apparently, crystallized melt) filling numerous microcracks developed throughout the entire volume of the sample was studied (Fig.4). This substance is a heterogeneous material enriched in alumina, iron and potassium (Table 3), as well as titanium. It was not possible to identify individual phases of this initially homogeneous, probably melt, substance in this work. However, the gross composition of inclusions in diamonds of this group given in Table 3 allows us to estimate the chemistry of the melt captured during crystallization. In general, it can be characterized as an iron- and potassium-enriched aluminosilicate melt containing water and volatile components and having the following average chemical composition, wt.%: SiO2 48-52; Al2O3 27-30; FeO 7-10; MgO is about 2, CaO is less than 1, K2O is on average 5.8-7.0. In the Kar-4 sample, more than 10 wt.% potassium was recorded in all inclusions (Fig.5, Table 3). The presence of a large number of fluid inclusions in the “northern” type dodecahedroids, especially in diamond crystals of varieties V-VII, is shown in [21, 34].

Table 2

Composition of clinopyroxene and garnet microinclusions from the Kar-15 diamond of the Bulkur site, wt.%

|

SiO2 |

TiO2 |

Al2O3 |

Cr2O3 |

FeO |

MgO |

CaO |

Na2O |

Total |

#Mg |

|

Cpx |

|||||||||

|

50.6 |

0.69 |

3.01 |

1.82 |

8.04 |

14.3 |

20.6 |

0.67 |

99.73 |

75.98 |

|

52.0 |

0.48 |

2.58 |

0.84 |

8.69 |

12.5 |

22.1 |

0.78 |

100 |

72.00 |

|

51.1 |

0.56 |

2.84 |

0.89 |

9.49 |

12.5 |

20.9 |

0.87 |

99.19 |

70.19 |

|

52.1 |

0.48 |

3.08 |

1.78 |

7.61 |

12.7 |

20.9 |

1.02 |

99.56 |

74.82 |

|

55.4 |

0.41 |

8.21 |

1.28 |

6.63 |

8.17 |

16.4 |

2.33 |

98.8 |

68.71 |

|

56.1 |

0.46 |

6.33 |

1.58 |

4.98 |

11.57 |

15.0 |

3.97 |

99.94 |

80.55 |

|

54.7 |

0.47 |

6.70 |

1.54 |

5.19 |

12.7 |

14.1 |

4.7 |

100.01 |

81.35 |

|

55.0 |

0.56 |

5.98 |

1.31 |

5.73 |

12.1 |

15.2 |

4.13 |

100.04 |

79.03 |

|

56.3 |

0.54 |

6.20 |

1.60 |

4.46 |

11.5 |

15.2 |

4.01 |

99.86 |

82.18 |

|

54.2 |

0.36 |

6.82 |

1.44 |

4.86 |

13.9 |

12.9 |

5.48 |

99.99 |

83.55 |

|

54.6 |

0.66 |

5.49 |

1.13 |

6.03 |

12.7 |

15.8 |

3.53 |

99.97 |

78.99 |

|

55.3 |

0.67 |

5.51 |

1.03 |

5.74 |

12.3 |

15.7 |

3.37 |

99.6 |

79.19 |

|

54.6 |

0.36 |

6.93 |

1.13 |

4.79 |

14.1 |

12.7 |

5.77 |

100.3 |

83.96 |

|

54.5 |

0.48 |

6.48 |

1.45 |

5.18 |

12.7 |

14.2 |

4.70 |

99.7 |

81.41 |

|

53.8 |

0.66 |

5.1 |

1.21 |

6.19 |

13.7 |

15.4 |

3.84 |

99.92 |

79.79 |

|

55.1 |

0.61 |

5.56 |

0.97 |

5.82 |

12.7 |

15.6 |

3.64 |

99.91 |

79.52 |

|

54.7 |

0.37 |

7.03 |

1.31 |

4.51 |

13.7 |

12.7 |

5.62 |

100 |

84.41 |

|

54.9 |

0.21 |

6.72 |

1.51 |

5.03 |

12.6 |

14.2 |

4.75 |

99.92 |

81.69 |

|

55.0 |

0.18 |

6.92 |

1.34 |

4.27 |

14.1 |

12.7 |

5.71 |

100.2 |

85.47 |

|

55.1 |

0.51 |

6.37 |

1.42 |

5.23 |

12.1 |

14.5 |

4.48 |

99.68 |

80.41 |

|

54.6 |

0.56 |

5.9 |

1.11 |

5.95 |

13.1 |

14.6 |

4.07 |

99.92 |

79.71 |

|

55.1 |

0.39 |

6.75 |

1.36 |

5.07 |

13.2 |

13.2 |

4.94 |

99.95 |

82.22 |

|

51.6 |

0.52 |

3.94 |

1.54 |

7.87 |

16.7 |

17.1 |

0.72 |

99.99 |

79.07 |

|

51.5 |

0.51 |

3.73 |

1.77 |

7.74 |

15.4 |

18.6 |

0.83 |

100 |

77.99 |

|

51.7 |

0.53 |

3.77 |

1.58 |

7.37 |

15.3 |

19.0 |

0.65 |

99.99 |

78.76 |

|

51.7 |

0.62 |

3.76 |

1.55 |

7.46 |

15.1 |

19.1 |

0.79 |

100 |

78.28 |

|

51.5 |

0.59 |

4.34 |

1.15 |

7.49 |

14.6 |

19.7 |

0.63 |

100 |

77.65 |

|

52.0 |

0.56 |

3.8 |

1.27 |

8.02 |

17.3 |

16.2 |

0.80 |

99.99 |

79.37 |

|

50.5 |

0.45 |

3.08 |

1.46 |

10.7 |

14.7 |

18.1 |

0.95 |

99.99 |

71.08 |

|

51.2 |

0.76 |

3.97 |

1.63 |

7.23 |

15.1 |

19.3 |

0.77 |

99.98 |

78.82 |

|

51.2 |

0.92 |

4.12 |

1.69 |

7.85 |

15.0 |

18.4 |

0.76 |

99.86 |

77.25 |

|

53.3 |

0.41 |

6.12 |

1.22 |

9.26 |

12.0 |

13.4 |

4.23 |

100 |

69.83 |

|

52.0 |

0.33 |

3.69 |

1.63 |

8.23 |

18.4 |

14.9 |

0.78 |

99.99 |

79.90 |

|

51.3 |

0.45 |

3.52 |

1.24 |

9.12 |

15.3 |

18.9 |

0.54 |

100.3 |

74.91 |

|

Grt |

|||||||||

|

42.3 |

0.25 |

21.1 |

1.5 |

15.5 |

14.9 |

4.43 |

|

99.99 |

63.2 |

Under conditions of decreasing temperature, phases of different composition are separated from the melt. In sample Kar-111, multiple separations of Ti-containing phases, including rutile, are clearly recorded (Fig.5, Table 3). Heterogeneity was also revealed in sample Kar-30. Table 3 shows two groups of compositions. In the first case (points 2, 5, 6), the composition is enriched in SiO2, Al2O3 and K2O; in the second (1, 3, 4), a decrease in the content of SiO2, Al2O3, and K2O is observed with a significant increase in iron.

Fig.4. Micrographs of dodecahedral habit diamond crystals with scars and partially crystallized melt inclusions: a sample Kar-34 in the BSE radiation (a), enlarged fragment of inclusion (b); a sample of Kar-30 in the BSE radiation (c), enlarged fragment of inclusions (d); a sample Kar-11 in cathodoluminescence (e); enlarged fragments of the Kar-11 sample (f-h).

The numbers indicate the chemical analyses corresponding to the dots in Table 3

Table 3

Chemical composition of melt matter in rounded diamonds with scars of the Bulkur site, wt.%

|

Kar-17-5 |

4 |

48.7 |

n/d |

28.8 |

14.3 |

2.58 |

0.35 |

5.33 |

100.1 |

Kar-111 |

Fe, Ti-oxides |

19 |

6.91 |

60.7 |

5.16 |

24.8 |

– |

0.65 |

0.76 |

99.0 |

||||

|

3 |

49.3 |

n/d |

28.7 |

13.5 |

2.63 |

0.32 |

5.48 |

99.93 |

18 |

7.68 |

68.9 |

5.62 |

20.3 |

– |

0.85 |

1.02 |

104.4 |

|||||||

|

2 |

49.6 |

n/d |

29.2 |

7.70 |

2.13 |

0.24 |

6.86 |

95.49 |

17 |

5.15 |

75.5 |

4.19 |

13.4 |

– |

0.69 |

0.69 |

99.62 |

|||||||

|

1 |

48.1 |

n/d |

27.9 |

10.7 |

2.44 |

0.21 |

6.31 |

95.45 |

16 |

1.93 |

89.0 |

1.84 |

5.28 |

– |

0.45 |

0.17 |

98.67 |

|||||||

|

Kar-11 |

4 |

50.3 |

n/d |

29.8 |

7.26 |

1.98 |

0.78 |

5.43 |

95.55 |

15 |

3.92 |

89.3 |

3.16 |

1.82 |

– |

0.49 |

0.66 |

99.35 |

||||||

|

3 |

52.5 |

0.23 |

30.3 |

6.30 |

3.86 |

1.00 |

5.61 |

99.8 |

Rutile |

14 |

1.67 |

91.6 |

1.76 |

3.21 |

– |

0.45 |

0.15 |

98.85 |

||||||

|

49.9 |

0.38 |

28.3 |

6.88 |

3.94 |

1.08 |

5.02 |

95.5 |

13 |

1.33 |

92.9 |

1.84 |

2.65 |

– |

0.46 |

0.10 |

99.18 |

||||||||

|

2 |

48.9 |

n/d |

29.1 |

9.36 |

2.34 |

0.77 |

5.1 |

95.57 |

K-bearing silicate phases |

12 |

48.7 |

0.91 |

27.2 |

9.05 |

2.23 |

0.86 |

5.78 |

94.7 |

||||||

|

50.6 |

n/d |

29.8 |

6.38 |

2.1 |

0.87 |

5.81 |

95.56 |

11 |

49.2 |

1.52 |

27.8 |

6.53 |

1.67 |

0.66 |

6.78 |

94.2 |

||||||||

|

1 |

47.8 |

n/d |

28.9 |

10.6 |

2.08 |

0.93 |

4.85 |

95.16 |

10 |

52.6 |

0.10 |

27.3 |

8.82 |

3.68 |

0.69 |

6.42 |

99.51 |

|||||||

|

48.2 |

0.10 |

29.2 |

9.72 |

2.14 |

0.84 |

5.12 |

95.22 |

8 |

53.4 |

0.12 |

28.1 |

8.70 |

1.79 |

0.96 |

7.04 |

100.1 |

||||||||

|

Kar-30 |

4 |

36.4 |

0.31 |

24.0 |

25.5 |

3.23 |

0.55 |

3.09 |

93.08 |

6 |

51.4 |

0.25 |

27.8 |

8.34 |

2.38 |

0.92 |

6.41 |

97.5 |

||||||

|

3 |

36.5 |

12.3 |

23.0 |

22.0 |

2.55 |

0.62 |

3.00 |

99.97 |

5 |

50.3 |

0.95 |

27.1 |

8.43 |

2.40 |

0.90 |

6.02 |

96.1 |

|||||||

|

1 |

35.7 |

0.92 |

23.1 |

23.4 |

2.61 |

0.60 |

3.64 |

89.97 |

4 |

50.1 |

0.10 |

27.3 |

8.46 |

2.31 |

0.94 |

6.36 |

95.47 |

|||||||

|

6 |

47.0 |

2.51 |

28.0 |

12.6 |

2.50 |

0.46 |

6.68 |

99.8 |

3 |

50.5 |

0.27 |

27.6 |

7.97 |

1.93 |

0.73 |

6.30 |

95.3 |

|||||||

|

5 |

49.1 |

0.70 |

29.4 |

10.6 |

2.04 |

0.61 |

5.93 |

98.38 |

2 |

51.0 |

0.41 |

27.1 |

6.63 |

2.73 |

0.73 |

6.16 |

94.8 |

|||||||

|

2 |

44.7 |

1.16 |

27.7 |

17.8 |

2.53 |

0.53 |

5.38 |

99.8 |

1 |

52.9 |

0.10 |

28.7 |

9.09 |

1.86 |

0.78 |

6.55 |

99.88 |

|||||||

|

Kar-34 |

4 |

43.6 |

0.03 |

26.5 |

15.7 |

2.27 |

0.78 |

5.19 |

94.04 |

Kar-4 |

24 |

44.6 |

1.80 |

25.6 |

11.5 |

3.44 |

1.84 |

11.2 |

99.98 |

|||||

|

3 |

47.8 |

0.01 |

27.4 |

11.4 |

2.36 |

0.81 |

5.61 |

95.38 |

23 |

42.6 |

2.31 |

23.4 |

14.2 |

5.41 |

1.49 |

10.7 |

100.1 |

|||||||

|

2 |

47.8 |

0.03 |

28.2 |

10.5 |

2.36 |

0.81 |

5.83 |

95.5 |

22 |

47.1 |

0.67 |

26.4 |

11.6 |

1.32 |

2.08 |

10.3 |

99.47 |

|||||||

|

1 |

48.7 |

0.15 |

27.1 |

8.8 |

4.05 |

0.9 |

5.84 |

95.54 |

18 |

50.1 |

1.12 |

28.0 |

6.70 |

1.53 |

1.92 |

10.4 |

99.72 |

|||||||

|

Components |

SiO2 |

TiO2 |

Al2O3 |

FeO |

MgO |

CaO |

K2O |

Total |

Components |

SiO2 |

TiO2 |

Al2O3 |

FeO |

MgO |

CaO |

K2O |

Total |

|||||||

Fig.5. Micrographs of rounded diamonds containing inclusions of a partially crystallized melt enriched in titanium, iron, and aluminum: a – general view of the Kar-111 sample; b, c – BSE image; d, f – general view of the Kar-4 sample and melt inclusions inside it; e – enlarged fragment of inclusion b; Rt – rutile; Fe, Ti-oxide – Fe- and Ti- oxides.

The compositions of the individual phases are shown in Table 3

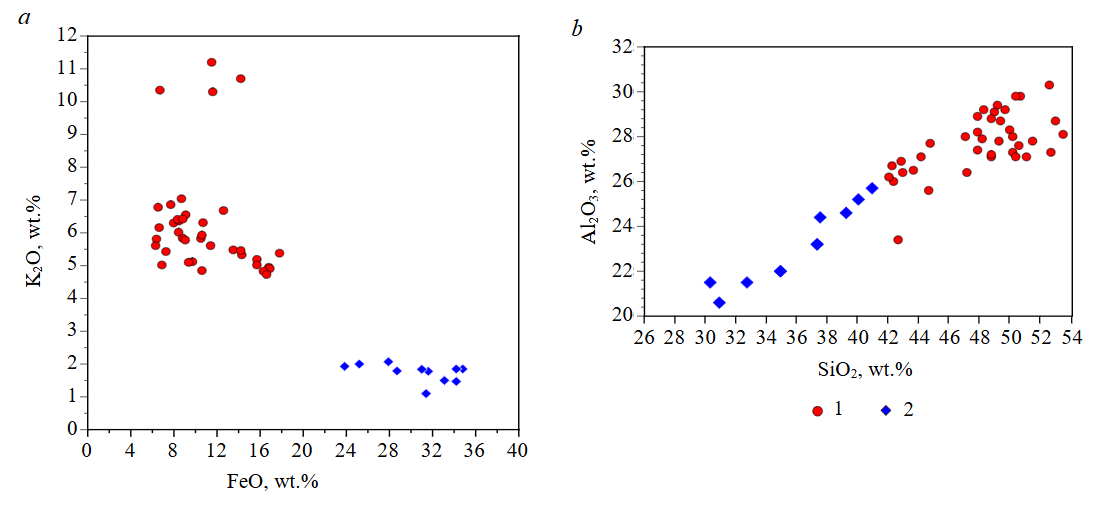

The process of transformation of aluminosilicate melt is shown most clearly using the example of two types of diamonds: dodecahedroid with scars Kar-10-17 and diamonds of the V variety Kar-81 and Kar-82 (Fig.6). All the separated phases in the radiation of backscattered electrons differ in color (lighter and darker). In the first case, the formed phases are subdivided into three groups by chemical composition. The dark part in the given inclusions has a uniform chemical composition, wt.%: SiO2 42.0-44.1; Al2O3 26-27.1; FeO 14.2-16.9; MgO 2.15-2.54; K2O 4.73-5.46. Light zones are characterized by an average 2.03-2.17 wt.% and a low 0.50-0.87 wt.% K2O content. They show a sharp increase in FeO, on average up to 40 wt.% (Table 4).

Diamonds V-VII according to Yu.L.Orlov classification. Melt inclusions in diamonds of the V-VII variety (Fig.6, d, e) are characterized by a low potassium content, not exceeding 2 wt.% K2O, and a high enrichment of iron from 25.2 to 34.6 wt.% FeO (Table 4). A distinctive feature of their composition is the stable presence of sulfates and chlorine (possibly chlorides). The main differences in the chemical composition of melt inclusions of the considered types of diamonds are shown in Fig.7. Melt inclusions in diamonds of dodecahedral habit with scars are more enriched in potassium, silica and aluminum, and in diamonds of the V-VII varieties such inclusions are distinguished by a higher iron content in the composition.

In the diamond of the V-VII varieties Kar-2, the TEM method recorded carbonatite polyphase nanosized inclusions of low-magnesium composition, represented by phases of SiO2, apatite, Ba, Sr-carbonate, Mg, Fe, K-silicate (not diagnosed) and multiple fluid vacuoles. Amorphous silica was also noted in this sample. Similar inclusions in alluvial diamonds of this type from the northeast of the Siberian craton are described in the article [34].

The source of such low-magnesium carbonatite melts-solutions could be subducted rocks of the oceanic and partially continental crust. Enrichment of such inclusions with incompatible elements may indicate the seepage of salt fluids enriched in Ba, Sr, P, Ti, K, Cl, through carbonated eclogites.

Fig.6. BSE images of rounded diamonds of the “northern” type: а – a sample Kar-10-17 (general view); b, c – enlarged fragments 1 and 2; d, e – inclusions in V-VII varieties diamonds (Kar-81 и Kar-82). The numbers indicate the points, the chemical compositions of which are given in Table 4

Table 4

Chemical composition of melt matter in the rounded diamond with scars and diamonds of the V-VII varieties (the Bulkur site), wt.%

|

Components |

Kar-10-17 (rounded diamond with scars) |

|||||||||||

|

Inclusion (fragment) 1 |

Inclusion (fragment) 2 |

|||||||||||

|

The dark part |

The light part |

The dark part |

The light part |

|||||||||

|

1 |

3 |

5 |

6 |

2 |

4 |

7 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

|

SiO2 |

42.3 |

42.0 |

42.8 |

44.1 |

27.5 |

26.6 |

20.1 |

42.9 |

42.2 |

51.8 |

32.2 |

34.2 |

|

Al2O3 |

26.0 |

26.2 |

26.9 |

27.1 |

19.5 |

19.3 |

11.3 |

26.4 |

26.7 |

21.5 |

23.1 |

23.6 |

|

FeO |

16.8 |

16.9 |

15.7 |

14.2 |

36.7 |

37.7 |

63.6 |

16.3 |

16.6 |

16.2 |

31.8 |

29.2 |

|

MgO |

2.54 |

2.45 |

2.28 |

2.15 |

3.14 |

3.19 |

n/d |

2.32 |

2.39 |

1.86 |

3.26 |

3.49 |

|

CaO |

0.33 |

0.34 |

0.32 |

0.30 |

0.31 |

0.38 |

n/d |

0.42 |

0.43 |

n/d |

0.31 |

0.35 |

|

K2O |

4.95 |

4.91 |

5.02 |

5.46 |

0.87 |

0.50 |

2.11 |

4.83 |

4.73 |

8.62 |

2.03 |

2.17 |

|

ZrO2 |

n/d |

n/d |

n/d |

n/d |

n/d |

n/d |

2.95 |

n/d |

n/d |

n/d |

n/d |

n/d |

|

Total |

92.9 |

92.8 |

93.02 |

93.31 |

88.02 |

87.67 |

100.1 |

93.2 |

93.05 |

99.98 |

92.7 |

93.01 |

|

Components |

Diamonds of varieties V-VII |

|

||||||||||

|

Kar-81 |

Kar-82 |

|

||||||||||

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

|

SiO2 |

37.3 |

37.5 |

39.2 |

37.9 |

40.9 |

32.7 |

30.9 |

30.3 |

34.9 |

37.3 |

40.0 |

|

|

Al2O3 |

23.2 |

24.4 |

24.6 |

24.0 |

25.7 |

21.5 |

20.6 |

21.5 |

22.0 |

23.2 |

25.2 |

|

|

FeO |

34.8 |

33.1 |

31.4 |

31.4 |

27.9 |

25.2 |

23.8 |

28.7 |

31.4 |

34.6 |

29.1 |

|

|

MgO |

2.39 |

2.71 |

2.81 |

2.23 |

3.03 |

4.51 |

4.84 |

4.44 |

2.23 |

2.39 |

3.03 |

|

|

CaO |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

0.85 |

2.67 |

0.62 |

– |

– |

0.19 |

|

|

K2O |

1.85 |

1.50 |

1.10 |

1.84 |

2.07 |

2.00 |

1.93 |

1.79 |

1.84 |

1.85 |

1.47 |

|

|

SO3 |

0.61 |

0.70 |

0.70 |

0.54 |

0.41 |

0.44 |

0.91 |

0.27 |

0.54 |

0.61 |

0.92 |

|

|

Cl |

0.10 |

0.09 |

0.08 |

0.09 |

0.09 |

0.09 |

0.08 |

0.10 |

0.09 |

0.11 |

0.08 |

|

|

Total |

100.25 |

100 |

99.81 |

98.0 |

100.1 |

87.2 |

85.8 |

87.72 |

93.0 |

100.06 |

99.91 |

|

Fig.7. Chemical composition of melt inclusions in Carnian diamonds of various types: a – K2O-FeO; b – Al2O3-SiO2

1 – dodecahedrons with scars; 2 – diamonds of varieties V-VII

Isotopic composition of carbon in diamonds

The carbon isotope composition of ten diamonds was studied: seven rounded dodecahedroids with scars and three kimberlite-type crystals – two octahedrons and one crystal of transitional form from octahedron to dodecahedron with laminar face structure. All dodecahedroids with scars showed a light carbon isotope composition, while the last three showed a heavy isotope composition (Table 5). This indicates differences in carbon sources for diamond formation and, consequently, different formation conditions.

Table 5

Carbon isotopic composition of diamonds from Carnian deposits

|

Sample number |

Crystal shape |

Color |

δ13С, ‰ |

|

Kar-72 |

Rounded dodecahedron (scars) |

Colorless |

–19.55 |

|

Kar-85 |

Rounded dodecahedron (scars) |

Colorless |

–20.36 |

|

Kar-86 |

Rounded dodecahedron (scars) |

Colorless |

–21.93 |

|

Kar-87 |

Rounded dodecahedron (scars) |

Colorless |

–22.33 |

|

Kar-88 |

Rounded dodecahedron (scars) |

Colorless |

–24.65 |

|

Kar-96 |

Rounded dodecahedron (scars) |

Colorless |

–23.25 |

|

Kar-100 |

Rounded dodecahedron (scars) |

Colorless |

–21.27 |

|

Kar-78 |

Octahedron |

Colorless |

–2.34 |

|

Kar-6А |

Transitional form |

Colorless |

–8.82 |

|

Kar-40 |

Octahedroid |

Colorless |

–10.21 |

Research results discussion

The studied diamonds (97 crystals) represent a polygenic mixture, generally characteristic of the northeast of the Siberian platform [11]. Among the studied diamonds, the following stand out: kimberlite-type diamonds; rounded dodecahedoids with scars; cuboids of the II variety; diamonds of the V-VII varieties.

Dodecahedroids with scars differ from other groups of diamonds. If diamonds of varieties V-VII and II are typical for the entire northeast of the platform and are distributed over an area of up to 400 thousand km2 [11], then the described rounded dodecahedroids in the Carnian deposits of Bulkur differ from dodecahedroids of the rest of the territory. First of all, this concerns the high defectiveness of Bulkur crystals, the presence of internal cracks filled with undiagnosed material, possibly epigenetic. In the process of opening these cracks during dissolution, scars are formed along them. Similar inclusions and scars are noted on diamonds of varieties V-VII, and the list of microinclusions in them is also similar (see Table 2). The study of the isotopic composition of carbon of the diamonds under consideration showed a light isotopic composition of carbon δ13C from –19.6 to –24.7 ‰. The carbon isotope composition of diamonds is one of the most important indicators of the source of the substance in genetic issues of diamond formation [35]. For most kimberlite diamonds, δ13C is from –4 to –8 ‰. It is believed that peridotite diamonds and eclogite diamonds close to them in isotopic composition were formed with the participation of mantle carbon [36]. The lighter isotopic composition of carbon indicates more complex subduction processes. Note that diamonds from ophiolites are also enriched in the light carbon isotope. The isotopic composition of carbon was characterized by δ13C values from –18.8 to –28.4 ‰ [37].

In placers, the percentage of diamonds enriched in the light carbon isotope is significantly higher. Alluvial diamonds of the V-VII varieties are characterized by δ13Cavg from –20 to –24 ‰ [38]. It could be assumed that dodecahedroids with scars are the result of deep dissolution of diamonds of the V-VII varieties, especially since they are completely similar in carbon isotope composition (Table 5) [39]. However, they differ in the concentration and forms of nitrogen aggregation (see Table 1). This type also differs in the chemical composition of the melt inclusions contained in the diamond. Such inclusions in dodecahedroids, compared to diamonds of the V-VII variety, are less ferrous (on average 12 and 31 wt.% FeO), and are also more enriched in potassium (on average 5.5 and 1.7 wt.% K2O). In addition, dodecahedroids are better crystallized, they have twin intergrowths, which cannot be found in diamonds of varieties V-VII, characterized by a ballas structure [40]. Cathodoluminescence microscopy makes it possible to reveal zonal inhomogeneities in natural diamond crystals and obtain information on the growth conditions and post-growth changes [41, 42]. The cathodoluminescence pattern in Fig.3 shows the growth zoning of the crystal, conformal to its surface, which indicates a low degree of dissolution. Therefore, the dodecahedral shape is probably close to the growth one and is formed in the process of rapid defective growth. We believe that the studied dodecahedroids with scars from the Carnian deposits of the Bulkur anticline represent a separate type of diamonds characteristic to the northeast of the platform. This type of diamonds is closest to diamonds of the V-VII varieties, differing in a slightly higher quality structure. In genetic terms, both varieties are close and are most likely associated with subduction. Dodecahedroids in other placers of this region have a more perfect structure. Thus, dodecahedroids from the placer of the Kuoika River (left tributary of the Olenek River) are characterized by jewelry quality [10].

For diamonds from placers in the northeastern Siberian platform, the authors of this article developed a classification scheme based on source types [11]: diamonds from Phanerozoic kimberlites; rounded dodecahedroids from Precambrian sources (presumably lamproites); yellow-orange cuboids of type II from Precambrian sources of unknown type; diamonds of types V-VII from Precambrian sources of unknown type; “yakutites” – diamonds of the Popigai astrobleme, present in Neogene-Quaternary placers. Only diamonds from Phanerozoic kimberlites are accompanied by indicator minerals, diamonds from Precambrian sources are not accompanied by indicators, or at least they have not been reliably identified, therefore it is difficult to determine the types of their source. We apply the same approach to characterizing diamonds from the Carnian stage of the Bulkur anteclise. Of the total diamond population, approximately 13 % are kimberlite, 51 % are scarred dodecahedroids, approximately 35 % are diamonds of varieties V-VII, and the rest are cuboids. Judging by the nature of the accompanying kimberlite indicator minerals, the kimberlite diamonds most likely originate from Early Triassic kimberlites [11, 43]. For the remaining diamonds, the authors of this article suggest their origin from unknown Precambrian sources.

Kimberlites, judging by the complete absence of mechanical wear of indicator minerals, diverse granulometry and their abundance in the Carnian deposits, are located in the immediate vicinity of the studied area [11]. However, finding them is extremely difficult due to the subsidence of the Carnian layer in the western directions. The presence of Precambrian diamonds is explained by the geological development of the region. From the end of the Permian, the Olenek uplift began to actively develop, as a result of which Precambrian deposits were exposed and actively eroded within its limits, in particular, Vendian clastic deposits, which are the most realistic intermediate reservoir for Precambrian diamonds throughout the Siberian platform [11]. At that time, the Predverkhoyansk trough did not yet exist and direct removal of clastic material, including diamonds, from the Olenek uplift to the Bulkur anticline area took place [7]. Within the Olenek uplift, diamonds from the Upper Triassic Rhaetian deposits, according to our research, are similar to those from Bulkur [3]. Geological reorganization of the region began at the end of the Mesozoic with the formation of the Verkhoyansk fold system, as a result of which the Bulkur region was separated from the Olenek uplift by the Pred-verkhoyansk trough. A geomorphological trap likely existed in the Bulkur region, resulting in the accumulation of a large number of diamonds here, whereas along the Carnian continuation in both directions from Bulkur, the number of diamonds decreases.

According to some researchers [4], the source of Carnian diamonds is Triassic kimberlites. Triassic dates have been obtained for kimberlite-type zircons [44], but this fact does not provide any evidence of the diamond potential of kimberlites. In this article, we assume a Precambrian age of the primary sources and their inclusion in Triassic and younger placers as a result of the erosion of Proterozoic coastal-marine deposits within the Precambrian projections, in particular on the Olenek uplift [11]. The proposed interpretation of the diamond potential of the Carnian stage within the Bulkur anticline fits in completely with the overall picture of the diamond potential of the Siberian platform [11]. In practical terms, both small-scale placer diamond potential and primary diamond potential are possible in the Bulkur anticline area. But its implementation is extremely complicated by the nature of the exploration situation, caused by the immersion of the productive layer in the western directions.

Conclusion

A polygenetic pattern based on typomorphism and source types has been proposed for Carnian diamonds. A type of kimberlite diamonds associated with Phanerozoic kimberlite bodies has been identified, along with three types of diamonds not typical of kimberlite bodies and associated with Precambrian sources of unknown type. The source type cannot be determined because the diamonds are not accompanied by corresponding indicator minerals, and conclusions can only be drawn from the diamonds themselves. Most of them have a light carbon isotope composition, suggesting a possible connection between their source and subduction processes.

Based on comprehensive studies of diamonds from Carnian deposits of the Bulkur anticline, a new type has been identified – rounded dodecahedroids with scars, which differ from dodecahedroids in the rest of the placer diamond field. This distinct type of alluvial diamond is likely characteristic to the northeastern Siberian craton.

It is assumed that the primary sources of the studied dodecahedral diamonds were Precambrian in age, and their inclusion in Triassic and younger placers can be explained as the result of erosion of Proterozoic coastal-marine deposits within Precambrian indentations, particularly on the Olenek uplift. This interpretation of the diamond potential of the Carnian stage within the Bulkur anticline is consistent with the general understanding of the diamond potential of the Siberian platform [11].

References

- Selivanova V.V. Typomorphism of diamond and its satellite minerals from the coastal-marine Triassic placers of the Northern Verkhoyansk region: Avtoref. dis. … kand. geol.-mineral. nauk. Moscow: Moskovskii ordena Trudovogo Krasnogo Znameni geologorazvedochnyi institut im. S.Ordzhonikidze, 1991, p. 20.

- Grakhanov S.A., Goloburdina M.N., Ivanov A.S., Aschepkov I.V. Mineralogical and petrographic characteristics of the diamond-bearing formations of the Bulkur anticline, Republic of Sakha (Yakutia). Regional Geology and Metallogeny. 2024. N 98, p. 41-63 (in Russian). DOI: 10.52349/0869-7892_2024_98_41-63

- Grakhanov S.A., Koptil V.I. Triassic diamond placers on the northeastern Siberian platform. Russian Geology and Geophysics. 2003. Vol. 44. N 11, p. 1189-1199.

- Grakhanov S.A., Goloburdina M.N. Ancient diamond placers of the Russian Federation. Regional Geology and Metallogeny. 2024. N 99, p. 68-106 (in Russian). DOI: 10.52349/0869-7892_2024_96_68-106

- Afanasev V.P., Zinchuk N.N., Pokhilenko N.P. Diamond prospecting mineralogy. Novosibirsk: Geo, 2010, p. 650 (in Russian).

- Goloburdina M.N., Grakhanov S.A., Proskurnin V.F. Petrographic composition of diamond-bearing Carnian formations of the Bulkur anticline the north-eastern Siberian Platform. Lithosphere. 2023. Vol. 23. N 4, p. 654-671 (in Russian). DOI: 10.24930/1681-9004-2023-23-4-654-671

- Sobolev N.V. On mineralogical criterions of diamond content in kimberlites. Geologiya i geofizika. 1971. N 3, p. 70-80 (in Russian).

- Ustinov V.N., Mikoev I.I., Piven G.F. Prospecting models of primary diamond deposits of the north of the East European Platform. Journal of Mining Institute. 2022. Vol. 255, p. 299-318. DOI: 10.31897/PMI.2022.49

- Zinchuk N.N., Koptil V.I. Typomorphism of the Siberian platform diamonds. Moscow: Nedra, 2003, p. 603 (in Russian).

- Zinchuk N.N., Koptil V.I. Specific features of diamonds from ancient sedimentary thick layers within crystalline massif influence areas. Otechestvennaya geologiya. 2020. N 3, p. 75-88 (in Russian). DOI: 10.24411/0869-7175-2020-10017

- Afanasiev V.P., Pokhilenko N.P. Approaches to the diamond potential of the Siberian craton: A new paradigm. Ore Geology Reviews. 2022. Vol. 147. N 104980. DOI: 10.1016/j.oregeorev.2022.104980

- Grakhanov S.A., Proskurnin V.F., Petrov O.V., Sobolev N.V. Triassic Diamondiferous Tuffaceous-Sedimentary Rocks in the Arctic Zone of Siberia. Russian Geology and Geophysics. 2022. Vol. 63. N 4, p. 458-482. DOI: 10.2113/RGG20214431

- Harris J.W., Smit K.V., Fedortchouk Y., Moore M. Morphology of Monocrystalline Diamond and its Inclusions. Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry. 2022. Vol. 88, p. 119-166. DOI: 10.2138/rmg.2022.88.02

- Walter M.J., Kohn S.C., Araujo D. et al. Deep Mantle Cycling of Oceanic Crust: Evidence from Diamonds and Their Mineral Inclusions. Science. 2011. Vol. 334. Iss. 6052, p. 54-57. DOI: 10.1126/science.1209300

- Stachel T., Harris J.W. The origin of cratonic diamonds – Constraints from mineral inclusions. Ore Geology Reviews. 2008. Vol. 34. Iss. 1-2, p. 5-32. DOI: 10.1016/j.oregeorev.2007.05.002

- Stachel T., Luth R.W. Diamond formation – Where, when and how? Lithos. 2015. Vol. 220-223, p. 200-220. DOI: 10.1016/j.lithos.2015.01.028

- Klein-BenDavid O., Izraeli E.S., Hauri E., Navon O. Mantle fluid evolution – a tale of one diamond. Lithos. 2004. Vol. 77. Iss. 1-4, p. 243-253. DOI: 10.1016/j.lithos.2004.04.003

- Klein-BenDavid O., Izraeli E.S., Hauri E., Navon O. Fluid inclusions in diamonds from the Diavik mine, Canada and the evolution of diamond-forming fluids. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 2007. Vol. 71. Iss. 3, p. 723-744. DOI: 10.1016/j.gca.2006.10.008

- Letnikova E.F., Lobanov S.S., Pokhilenko N.P. et al. Sources of Clastic Material in the Carnian Diamond-Bearing Horizon of the Northeastern Part of the Siberian Platform. Doklady Earth Sciences. 2013. Vol. 451. Part 1, p. 702-705. DOI: 10.1134/S1028334X13070131

- Orlov Yu.L. Diamond mineralogy. Мoscow: Nauka, 1984, p. 170.

- Smith E.M., Kopylova M.G., Frezzotti M.L., Afanasiev V.P. Fluid inclusions in Ebelyakh diamonds: Evidence of CO2 liberation in eclogite and the effect of H2O on diamond habit. Lithos. 2015. Vol. 216-217, p. 106-117. DOI: 10.1016/j.lithos.2014.12.010

- Stachel T., Aulbach S., Harris J.W. Mineral Inclusions in Lithospheric Diamonds. Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry. 2022. Vol. 88, p. 307-391. DOI: 10.2138/rmg.2022.88.06

- Gubanov N.V., Zedgenizov D.A., Vasilev E.A., Naumov V.A. New data on the composition of growth medium of fibrous diamonds from the placers of the Western Urals. Journal of Mining Institute. 2023. Vol. 263, p. 645-656.

- Reutsky V.N., Borzdov Yu.M., Palyanov Yu.N. Effect of diamond growth rate on carbon isotope fractionation in Fe–Ni–C system. Diamond and Related Materials. 2012. Vol. 21, p. 7-10. DOI: 10.1016/j.diamond.2011.10.001

- Wirth R. Focused Ion Beam (FIB): A novel technology for advanced application of micro- and nanoanalysis in geosciences and applied mineralogy. European Journal of Mineralogy. 2004. Vol. 16. N 6, p. 863-876. DOI: 10.1127/0935-1221/2004/0016-0863

- Wirth R. Focused Ion Beam (FIB) combined with SEM and TEM: Advanced analytical tools for studies of chemical composition, microstructure and crystal structure in geomaterials on a nanometre scale. Chemical Geology. 2009. Vol. 261. Iss. 3-4, p. 217-229. DOI: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2008.05.019

- Green B.L., Collins A.T., Breeding C.M. Diamond Spectroscopy, Defect Centers, Color, and Treatments. Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry. 2022. Vol. 88, p. 637-688. DOI: 10.2138/rmg.2022.88.12

- Ashfold M.N.R., Goss J.P., Green B.L. et al. Nitrogen in Diamond. Chemical Reviews. 2020. Vol. 120. Iss. 12, p. 5745-5794. DOI: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00518

- Speich L., Kohn S.C., Bulanova G.P., Smith C.B. The behaviour of platelets in natural diamonds and the development of a new mantle thermometer. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology. 2018. Vol. 173. Iss. 5. N 39. DOI: 10.1007/s00410-018-1463-4

- Goss J.P., Briddon P.R., Hill V. et al. Identification of the structure of the 3107 cm−1 H-related defect in diamond. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter. 2014. Vol. 26. N 14. N 145801. DOI: 10.1088/0953-8984/26/14/145801

- Vasilev E.A. Defects of diamond crystal structure as an indicator of crystallogenesis. Journal of Mining Institute. 2021. Vol. 250, p. 481-491. DOI: 10.31897/PMI.2021.4.1

- Molotkov A.E., Pavlushin A.D., Smelov A.P. et al. Defect-impurity composition of diamonds from Carnian deposits of the north eastern Siberian platform. Otechestvennaya geologiya. 2014. N 5, p. 74-79 (in Russian).

- Weiss Y., Czas J., Navon O. Fluid Inclusions in Fibrous Diamonds. Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry. 2022. Vol. 88, p. 475-532. DOI: 10.2138/rmg.2022.88.09

- Logvinova A.M., Wirth R., Tomilenko A.A. The phase composition of crystal-fluid nanoinclusions in alluvial diamonds in the northeastern Siberian Platform. Russian Geology and Geophysics. 2011. Vol. 52. N 11, p. 1286-1297. DOI: 10.1016/j.rgg.2011.10.002

- Galimov E.M. Isotope fractionation related to kimbelite magmatism and diamond formation. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 1991. Vol. 55. N 6, p. 1706-1708. DOI: 10.1016/0016-7037(91)90140-Z

- Kan Li, Long Li, Pearson D.G., Stachel T. Diamond isotope compositions indicate altered igneous oceanic crust dominates deep carbon recycling. Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 2019. Vol. 516, p. 190-201. DOI: 10.1016/j.epsl.2019.03.041

- Weiwei Wu, Jingsui Yang, Wirth R. et al. Carbon and nitrogen isotopes and mineral inclusions in diamonds from chromitites of the Mirdita ophiolite (Albania) demonstrate recycling of oceanic crust into the mantle. American Mineralogist. 2019. Vol. 104. Iss. 4, p. 485-500. DOI: 10.2138/am-2019-6751

- Ragozin A.L., Shatskii V.S., Zedgenizov D.A. New Data on the Growth Environment of Diamonds of the Variety V from Placers of the Northeastern Siberian Platform. Doklady Earth Sciences. 2009. Vol. 425A. N 3, p. 436-440. DOI: 10.1134/S1028334X09030192

- Ragozin A.L., Zedgenizov D.A., Kuper K.E., Shatsky V.S. Radial mosaic internal structure of rounded diamond crystals from alluvial placers of Siberian platform. Mineralogy and Petrology. 2016. Vol. 110. Iss. 6, p. 861-875. DOI: 10.1007/s00710-016-0456-0

- Pavlushin A., Zedgenizov D., Vasilev E., Kuper K. Morphology and Genesis of Ballas and Ballas-Like Diamonds. Crystals. 2021. Vol. 11. Iss. 1. N 17. DOI: 10.3390/cryst11010017

- Wiggers de Vries D.F., Drury M.R., de Winter D.A.M. et al. Three-dimensional cathodoluminescence imaging and electron backscatter diffraction: tools for studying the genetic nature of diamond inclusions. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology. 2011. Vol. 161. Iss. 4, p. 565-579. DOI: 10.1007/s00410-010-0550-y

- Vasilev E., Zedgenizov D., Zamyatin D. et al. Cathodoluminescence of Diamond: Features of Visualization. Crystals. 2021. Vol. 11. Iss. 12. N 1522. DOI: 10.3390/cryst11121522

- Nikolenko E.I., Logvinova A.M., Izokh A.E. et al. Cr-spinel assemblage from the Upper Triassic gritstones of the northeastern Siberian Platform. Russian Geology and Geophysics. 2018. Vol. 59. N 10, p. 1348-1364. DOI: 10.1016/j.rgg.2018.09.011

- Agashev A.M., Chervyakovskaya M.V., Serov I.V. et al. Source rejuvenation vs. re-heating: Constraints on Siberian kimberlite origin from U–Pb and Lu–Hf isotope compositions and geochemistry of mantle zircons. Lithos. 2020. Vol. 364-365. N 105508. DOI: 10.1016/j.lithos.2020.105508