Recent advances in petrophysical properties, mechanical behavior and durability of calcarenite rocks

- Head of the Geotechnical Laboratory University of Bari Aldo Moro ▪ Orcid

Abstract

Recent research on predicting petrophysical and mechanical properties of carbonate rocks, integrating textural and microstructural observations with geotechnical measurements, has sparked critical discussions. While some studies present robust experimental methods and fresh insights, others rely on less rigorous approaches. In the Mediterranean area, shallow-water calcarenites crop out along both the coastline and internal areas. Typically, these carbonates are soft and exhibit high porosity, open in type, controlled by the depositional fabric and post-depositional processes. Their strength primarily depends on the type and amount of calcite cement, with water presence significantly impacting their stress-strain behavior. Strength and stiffness decrease markedly in the transition from dry to saturated conditions. Well-cemented calcarenites with early and late diagenetic cement exhibit brittle behavior in both dry and saturated states, whereas poorly cemented types with early calcite cementation alone show brittle behavior when dry and pseudo-ductile to ductile behavior when saturated. Dual-porosity systems, combining micro- and macro-pores, dominate the hydraulic properties of calcarenites, playing a key role in decay mechanisms and patterns. This study compares existing literature with laboratory analyses of calcarenite lithofacies from Apulia and Basilicata (Southern Italy), yielding new insights into their mechanical and physical behavior, as well as durability.

Funding

This research was supported by MIUR (Italian Ministry of Education, University and Research) under Grant 2010 ex MURST 60 % ‘‘Modelli geologico-tecnici, idrogeologici e geofisici per la tutela e la valorizzazione delle risorse naturali, ambientali e culturali’’ (coordinator G.F.Andriani). The research was financially supported by European Community within the Project Interreg III A “WET SYS B” 2000-2006 (responsible G.F.Andriani) and Apulia Region within the Program “CT14” (responsible G.F.Andriani). Work carried out within the framework of the Project MIUR (Italian Ministry of Education, University and Research) 2017-2018 ex MURST 60 % “Engineering geology and hydrogeological studies applied to the protection, development and promotion of geo-resources and historical, artistic and geo-environmental heritage” (responsible G.F.Andriani).

Introduction

Calcarenites are typically characterized by intermediate strength between soils and hard rocks, and show progressive modifications in mechanical behaviour resulting from changing boundary conditions, including stress state, loading method and saturation degree. They exhibit transition from rock-like to soil-like behaviour, both on a large and small scale, due to destructuration processes and are characterized by a complex physical-mechanical response controlled by fabric, including texture and structure both microscopic and macroscopic, and bonding, mainly due to syndepositional and diagenetic cementation. Furthermore, at the rock mass scale, post-depositional tectonic episodes and groundwater circulation have to be considered. Thus, specific interrelationships exist between depositional facies and post depositional processes and overall strength of these materials, including weathering resistance [1-4]. Kanji [5] has recently published a synthesis of the literature and studies on the physico-mechanical properties of soft rocks, including calcarenites and other lithotypes, showing reliable problems in utilizing current and widespread methods for their classification and characterization.

The pore structure of calcarenites is complex, as they are allochemical rocks composed of grains consisting mainly of fossiliferous material, intraclasts, ooids, and peloids, which are embedded in the micrite matrix and cement. The cement is mostly composed of early diagenetic calcite, neomorphic microsparite, and, to a lesser extent, late diagenetic calcite in the form of sparite, in other words coarse crystalline calcite that fills pore spaces. Despite this complex texture and pore structure, many authors agree that these materials are characterized by open porosity, although it is of a dual type due to the presence of both micropores and macropores [6]. In fact, a highly open porous texture has been widely documented through the combination of 2D and 3D methodological approaches and simple vacuum imbibition tests using water [2, 7]. On the contrary, Festa et al. [8] propose a prevailing closed-pore network made up of intragranular pores and, to a lesser extent, mouldic and separate-vug pores, although this statement is based on 2D thin section petrography observations and on questionable geotechnical data, elaborated and interpreted in a decidedly dubious manner [9]. Furthermore, recent studies on the physical and mechanical behaviour of some Plio-Pleistocene lithofacies of the calcarenites cropping out in Apulia and Basilicata showed different mechanisms of material weakening for short- and long-term interaction with water by means of Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM), Mercury Intrusion Porosimetry (MIP), thin sections and X-ray Micro-computer Tomography (MCT) analyses [1, 2, 7]. These complex mechanisms need highly open porous textures and particular types of bonding in order to develop.

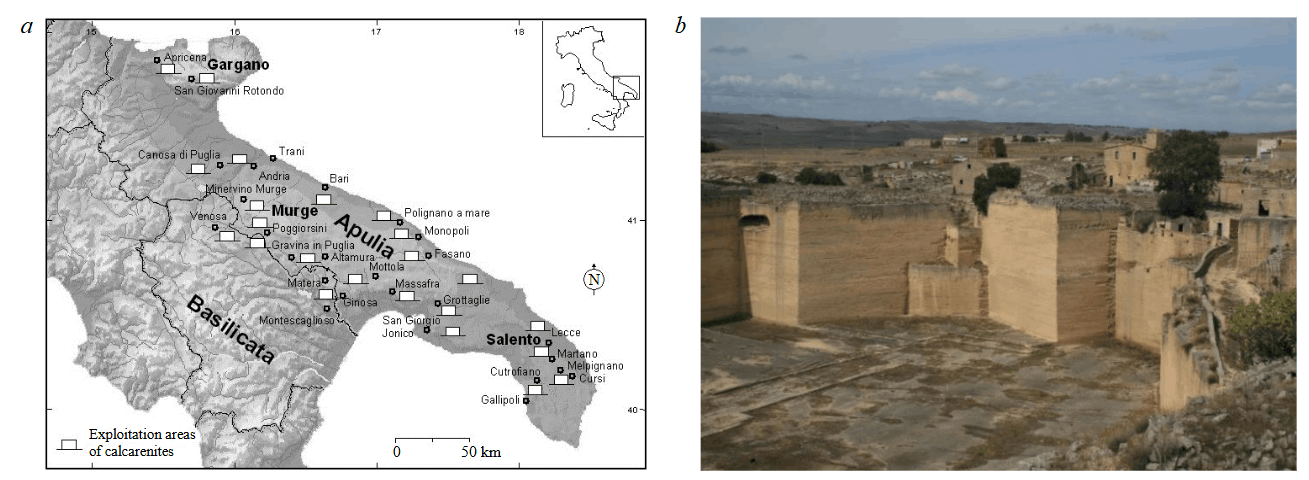

Calcarenites are ubiquitous in their worldwide distribution and are generally interpreted as the result of depositional and diagenetic processes in both modern and ancient marine and non-marine environments. Porosity and permeability features give them excellent fluid accumulation capacity and drainage properties which characterize important hydrocarbon and water systems in North Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, Mexico, Australia, the North Sea and the Mediterranean basin, comprising some areas of South Italy. In Apulia and Basilicata, calcarenite sequences crop out particularly along both the coastline and the inner Murge edge, in correspondence of hill slopes, valley cliffs and quarry walls (Fig.1). These calcarenites belong mainly to the Calcarenite di Gravina (Middle Pliocene – Lower Pleistocene) and are constituted by fine-, medium- and coarse-grained packstones and grainstones [2, 10]. Oligocene-Miocene open-shelf sequences, belonging to the Calcareniti di Porto Badisco (Upper Oligocene), Lecce (Upper Oligocene – Lower Miocene) and Pietra Leccese (Upper Burdigalian – Lower Messinian) formations, are widely exposed in the Salento Peninsula (South Apulia). Specifically, the Pietra Leccese formation is represented by porous biomicrites, fine- to medium-grained packstone-wackestone in types, widely used as stone material in the built heritage of the Baroque architecture in the Salento Peninsula [11, 12]. In general, it can be stated that the calcarenites have a noteworthy historical importance not only linked to their use over time as building material but also because ancient habitations, rupestrian churches, animal shelters, and underground caves were dug into this rock since prehistoric times. Additionally, these materials are important in constituting significant hydrogeological units which control groundwater recharge and transport of contaminants within a complex, multilayered system comprising a wide and deep aquifer hosted in the Mesozoic carbonate basement [2, 13, 14].

Fig.1. Principal exploitation areas of the calcarenites from Apulia and Basilicata (a); quaternary calcarenites outcrops along the walls of an ancient quarry (b), Poggiorsini, Grottelline locality, Apulia

This study aims to enhance the understanding of the physical and mechanical properties of calcarenite rocks, based on both new experimental data and a critical review of existing literature. By employing a combination of standard and unconventional testing methods, this work not only introduces new findings but also critically examines and refines existing concepts in the field. A review of recent and historic studies, alongside new experimental data, suggests that some fundamental concepts concerning the physical and mechanical behavior of calcarenites require clarification and refinement. The analysis emphasizes the relationship between these properties and the depositional and diagenetic characteristics of calcarenites, focusing on their textural and structural features, and offering new insights into their behavior. Such knowledge is essential for a wide range of geo-engineering applications, particularly in hydrogeology and stability-related issues, as well as for restoration and conservation of both modern constructions and historic and artistic heritage.

Methods

New findings from experimental analysis on the calcarenites from Apulia and Basilicata and results from previous studies on the same units and other similar calcarenites cropping out in different geographic regions have been used to show the significant textural elements which affect the mechanical and physical behavior of carbonate soft rocks. By comparing and combining analysis of the experimental results obtained for this study with literature data and information, a critical assessment of petrophysical and mechanical properties of these materials was carried out, suitable for deriving relationships between the different parameters and evaluating its susceptibility to weathering.

For this study, a multidisciplinary approach using traditional methods of investigation associated with new experimental unconventional techniques was used. Accordingly, this study collects 127 calcarenite blocks from quarries and natural outcrops in Apulia and Basilicata. In particular, rectangular blocks belonging to the Calcarenite di Gravina formation were taken from the quarry areas of Altamura, Canosa di Puglia, Gravina in Puglia, Massafra, Matera, Minervino Murge, Montescaglioso, and Poggiorsini. Polyhedral blocks of the same geological formation were taken from fresh outcrops in the sites of Mottola, Monopoli and Polignano a mare. Conversely, rectangular blocks belonging to the Pietra Leccese formation were taken from the quarry areas of Cursi and Melpignano. Standard thin-sections were also prepared to examine rock fabric by means of optical polarizing microscopy with transmitted light. Circular cylinders of 54 mm in diameter were prepared, according to the ASTM Standard D4543-19. The specimen length to diameter ratios were between 2.0:1 and 2.5:1. The apparent density of both dry and water saturated conditions was calculated by mass volume ratio according to the Method B of the ASTM Standard D7263-16. The determination of effective porosity of the samples was obtained by using water immersion method, according to research [2, 9]. The experimental procedure requires an analytical balance with a capacity of 2000 g and a precision of one thousandth for hydrostatic weighing, a PC water bath, a vacuum pump, and a vacuum desiccator. The specimens are first weighed in air and then weighed in distilled water at 20 °C for 48 h, which is the typical time required to obtain a seemingly constant value for hydrostatic weighing. In the second phase of the experiment, the samples are completely saturated under vacuum (80 kPa) without removing them from the water bath. This method also allows for the determination of the water absorption and the degree of saturation. Full saturation (Sr = 100 %) was achieved for almost all the facies studied.

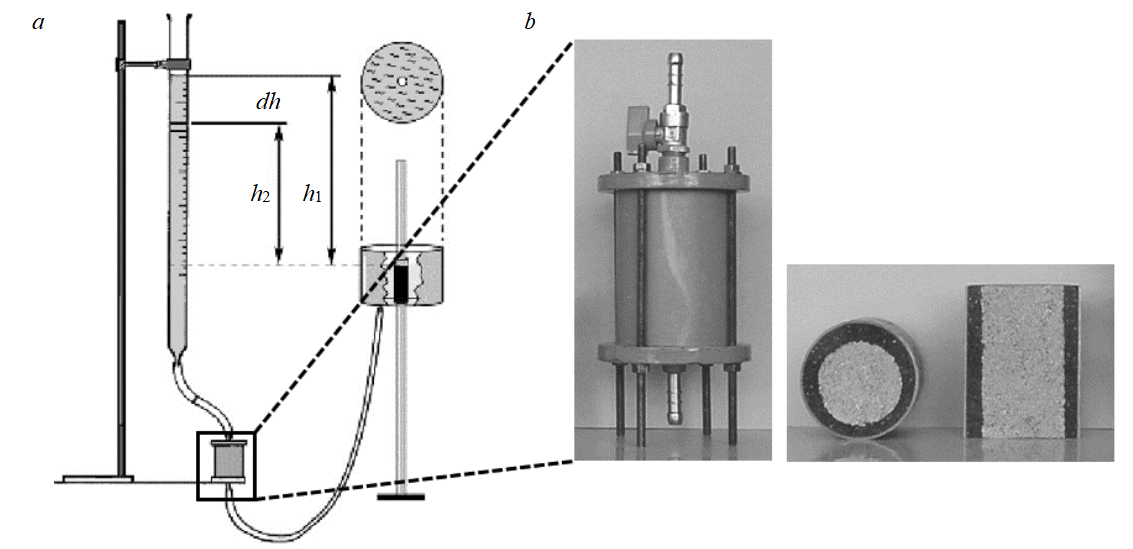

The procedure for measuring uniaxial compressive strength (UCS) was performed on dry and saturated samples, according to the ISRM suggested method for intact rocks [15], by imposing a load constant stress rate of 0.2 MPa/s. Low load rate was selected in order to better examine the progress to failure and stress – strain behaviour of these soft rock materials. The modulus of elasticity was derived from the UCS test on dry samples from the slope of the stress – strain curves by tangent modulus (Et). Disc specimens (diameter of 54 mm, height to diameter ratio – 0.5:1) were prepared from cylinder specimens and used for the indirect tensile strength test (Brazilian test). Rectangular (370×150×110 mm) and polyhedral blocks (about 1.75 dm3) were used for Schmidt hammer test. A Type N hammer was used, according to Aydin [16]. Water permeability tests were conducted in a purpose-built cell on cylindrical rock samples (diameter 71 mm and height 140 mm) using the falling head method. The hydraulic conductivity k20 standardized at 20 °C was evaluated for a range of hydraulic gradients between 0.5 and 15 (Fig.2). Thermal properties of the calcarenites were obtained from the measurement of the thermal linear expansion coefficient al, based on mechanical length-change measurements at 20, 40, 60 and 80 °C on rock bars of 350×15×15 mm according to Popov et al. [17]. The thermal conductivity l in variable regime was obtained on two specimens for each study site by means of the experimental “cut-core” method [18]; measurements were taken on the same samples first in the dry state and then in the saturated state.

Fig.2. Scheme of the water permeability test instrument (a); permeability built cell for cylindrical rock samples and laboratory prepared transversal and longitudinal sections of specimens (b)

Results

Table 1 summarizes the main test results on the calcarenites from Apulia and Basilicata analyzed in the context of this study.

Table 1

Physical and mechanical properties of the calcarenites from Apulia and Basilicata

|

Properties |

Calcarenite di Gravinaformation |

Pietra Lecceseformation |

|

Specific gravity Gs (average) |

2.70 |

2.70 |

|

Unit weight (dry) γd, kN/m3 |

12.0-18.2 |

15.3-19.0 |

|

Unit weight (saturated) γs, kN/m3 |

17.6-21.5 |

19.6-22.0 |

|

Total porosity n, % |

33-56 |

30-43 |

|

Water absorption wa, % |

18-46 |

16-28 |

|

Degree of saturation Sr, % |

100 |

100 |

|

Hydraulic conductivity k20, 10–5·m/s |

1.2-14.0 |

4.5-7.5 |

|

Thermal linear expansion al, 10–6·K–1 |

1.95-3.50 |

3.34-5.21 |

|

Thermal conductivity (dry) λd, W·m–1·K–1 |

0.61-1.13 |

0.64-1.10 |

|

Thermal conductivity (saturated) λs, W·m–1·K–1 |

1.12-1.64 |

0.82-1.53 |

|

Compressive Strength (dry) σn, MPа |

1.1-7.3 |

12.8-23.4 |

|

Tangent Modulus (dry) Et, GPа |

0.5-10 |

3.5-14 |

|

Compressive Strength (saturated) σs, МPа |

0.7-4.9 |

7.1-12.2 |

|

Indirect Tensile strength (dry) σtd, МPа |

0.11-1.1 |

1.2-2.7 |

|

Indirect Tensile strength (saturated) σts, МPа |

0.08-0.8 |

0.42-1.5 |

|

Schmidt Rebound Number (dry) Rl |

0 |

10-24 |

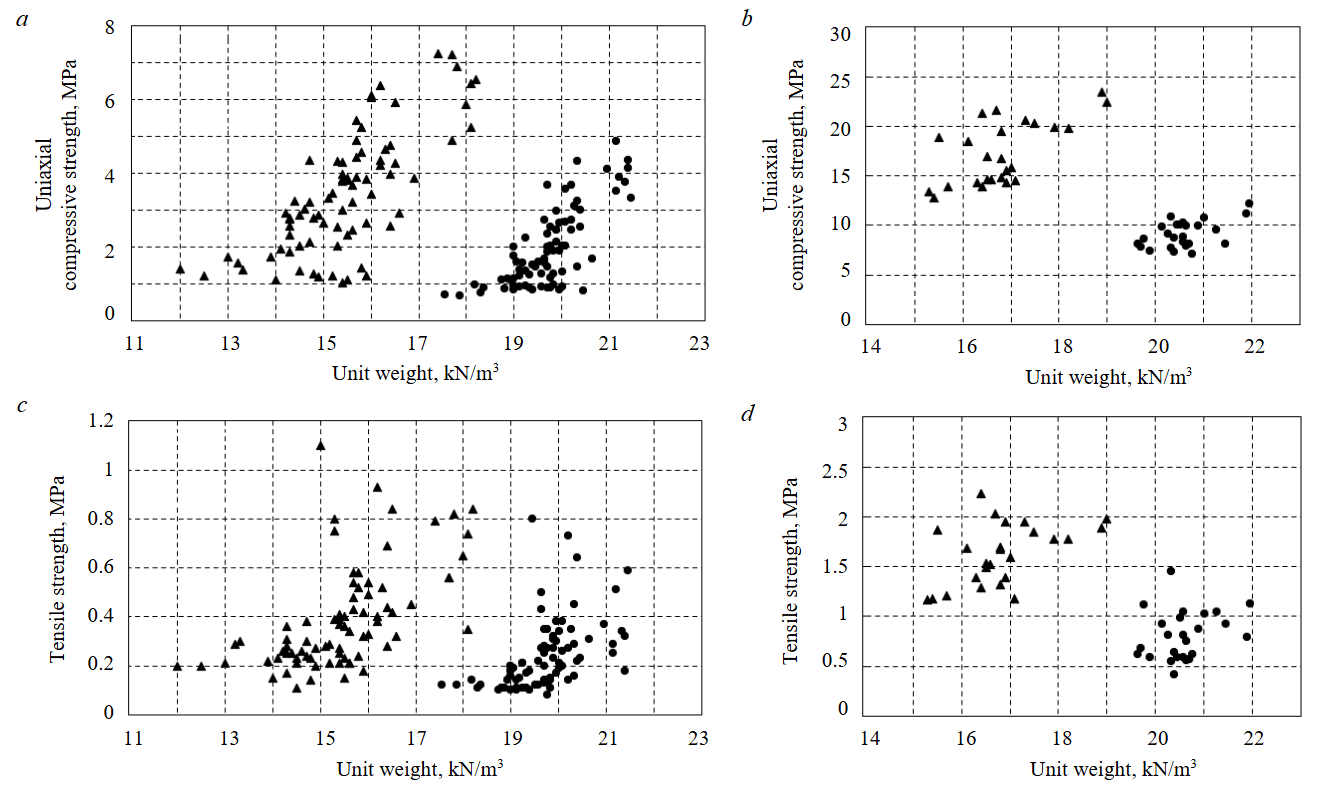

In particular, Fig.3, a, b shows the results of the uniaxial compression test for the Calcarenite di Gravina and Pietra Leccese formations in terms of uniaxial strength as a function of unit weight, distinguishing the results obtained from dry and saturated samples, while Fig.3, c, d shows the results of the Brazilian tensile strength test for the same formations in terms of tensile strength as a function of unit weight, distinguishing the results obtained from dry and saturated samples.

Fig.3. Uniaxial compression strength plotted against unit weight for samples belonging to the Calcarenite di Gravina formation (a) and the Pietra Leccese formation (b); tensile strength plotted against unit weight for samples belonging to the Calcarenite di Gravina formation (c) and the Pietra Leccese formation (d)

♦ – dry conditions; • – saturated conditions

Discussion

Petrophysical properties. Calcarenite is a clastic limestone characterized predominantly by a grain-size range of 0.0063-2.00 mm in diameter. Basically, according to Folk [19], it is a carbonate sandstone constituted by a framework of calcitic or aragonitic grains, allochems. The main allochems consist of bioclasts, pellets, ooids, and intraclasts. Spaces between grains are partially or completely filled by micrite matrix and/or sparite cement. Micrite matrix is microcrystalline lime-mud with a particle size finer than 30 μm. It may be originated by biological and/or physical erosion of coarser carbonate grains, post mortem disintegration of aragonitic calcareous algae, inorganic precipitation from carbonate saturated waters and biochemical precipitation by algal activity. Wherever the calcite matrix is affected by recrystallization and neomorphic processes, it takes the term “microspar” which occurs as fine grained calcite microcrystals, 4-10 μm in size, uniform in shape and size. Sparite cement or sparry calcite cement is produced by the precipitation of calcite from carbonate-rich solutions passing through the pore spaces in the sediment. It consists of coarse calcite crystals, 0.03-1.0 mm in size, occurring immediately after deposition or immediately after burial (early diagenesis) and a long time after deposition and during burial (late diagenesis). Carbonate cements can be subdivided into numerous important types on the basis of Mg/Ca ratio and salinity of the solution.

Generally, blocky or mosaic cement, which is formed in freshwater and phreatic environment, is widespread in the lithofacies characterized by the highest UCS and/or indirect tensile strength (ITS) values. In the Mediterranean Basin, most subaerial outcrop surfaces in calcarenite sequences occur along exposures of sea or valley cliffs and quarry walls. They are mainly massive bedded or medium-bedded, well-sorted calcarenites accumulated in beach foreshore and shoreface environments. These environments include a great variety of physical and biological processes which produce different sedimentary facies, texturally and structurally distinct and conditioned also by the topography of the underlying bedrocks.

After deposition, due to diagenetic processes such as compaction, cementation, dissolution, recrystallization, changes or obliterations of pre-existing fabrics occur. Pore-size distribution, pore types, pore network topology, and physical parameters of calcarenites are the result of both depositional and postdepositional processes, including diagenesis and weathering. Consequently, pore system in calcarenite rocks is very complex due to small-scale facies heterogeneities which lead to the co-presence of both effective and closed pore types, even though the latter with lower development or absent. Furthermore, open porosity, at the sample scale, is characterized by a wide range of pore sizes and pore types, including large and medium capillary pores, and entrained air pores, sensu Mindess et al. [20], and show a uniform connectivity in the pore system. The pore structure consists of complex and tortuous networks. These involve mainly arrangements of interparticle, intraparticle, mouldic, vug, boring, burrow and cement/matrix intercrystal pores, sensu Choquette and Pray [21], interconnected by pore throats, in which microcraks (through pores) can be indented. Pore throat sizes and distributions depend on grain packing and arrangement, sizes and shapes of grains and crystals, and energy of deposition. They generally range from 0.01 to 5 μm, although microcracks can be greater than 63 μm. Throats and intercrystal pores are assessed by capillary pressure measurements, being often too small to be analyzed in thin sections [22].

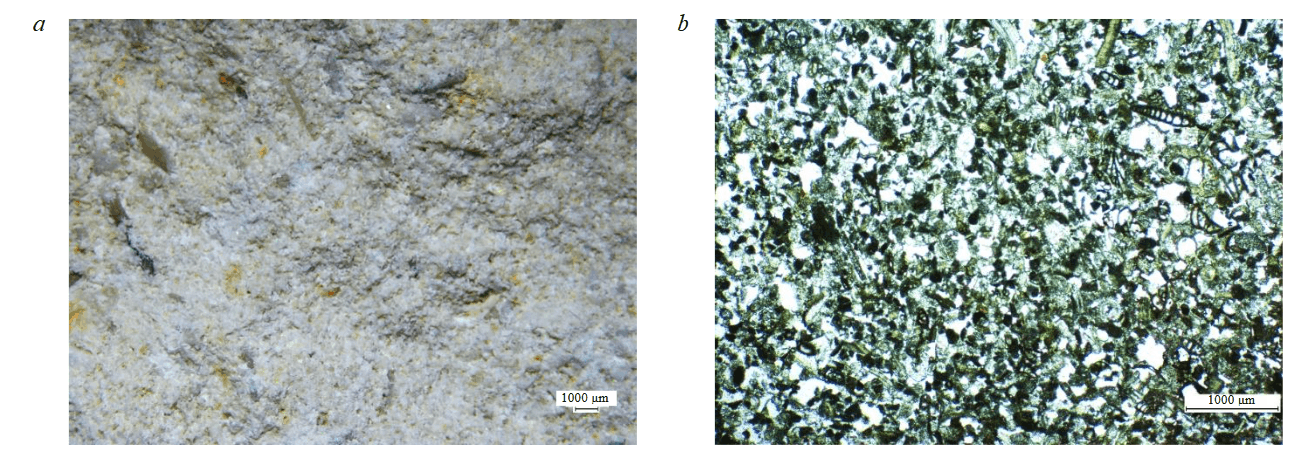

The dominant pore types are different for the different facies, but it can be stated that interparticle, intraparticle and intercrystal pores are present everywhere. In particular, pores in the fabric of almost all the lithofacies in Apulia and Basilicata and, particularly, for those belonging to the Calcarenite di Gravina formation, are mainly interconnected and continuous. This is also due to the fact that for the most widespread lithofacies belonging to the Calcarenite di Gravina formation (fine-grained bioclastic wackestone, medium-grained bioclastic or bio-lithoclastic packstone, medium- to coarse-grained bioclastic or bio-lithoclastic grainstone) the degree of packing is low due to a precocious diagenesis occurred with or very soon after deposition (Fig.4). Therefore, cement precipitation begins in the early stages of compaction or even before burial induces an increase in pressure and temperature. Not surprisingly, early-stage cement in the form of meniscus calcite cement is present at grain contacts in many calcarenite lithofacies in Apulia and Basilicata. This type of cement is complemented by a border of fine calcite crystals on the grain surfaces, at some places surrounded by scalenohedronic or rhombohedral elongated crystals and microcrystals (“dog tooth” cement). It follows that low degree of compaction and scarce cementation lead to high connectivity of the pore network and therefore high effective or open porosity and low or non-existent closed-porosity. The only exceptions are caliche and rudstone intervals where pores are occluded by vadose blocky low-Mg calcite cement, even though, according to Wright [23], caliche should be dealt with separately from calcareous tufas and similar materials.

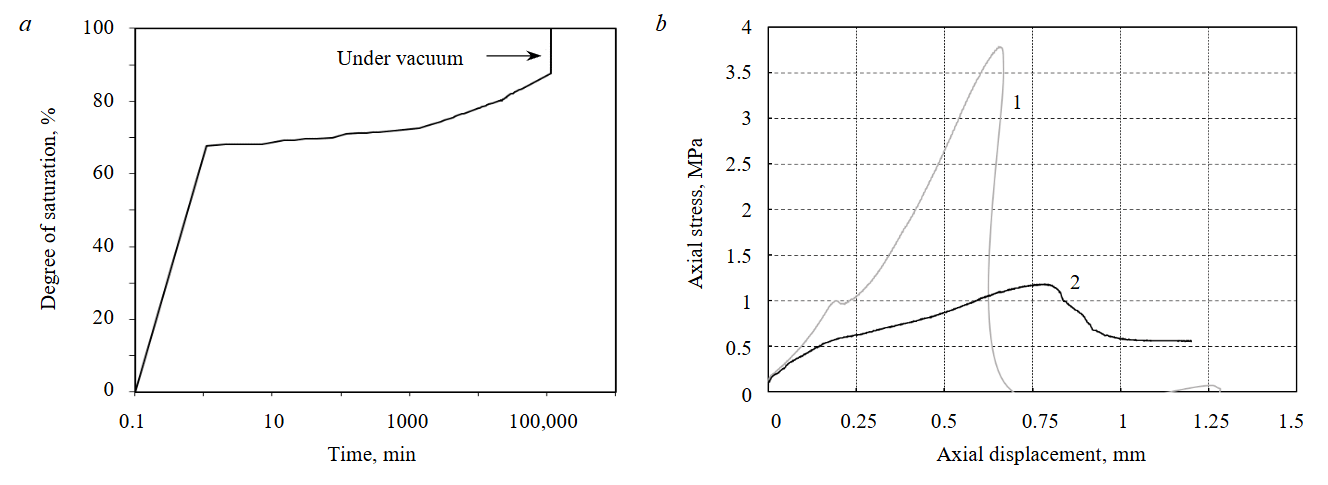

With particular regard to the Pietra Leccese formation (fine- to medium-grained bioclastic wackestone, fine- to medium-grained bioclastic packstone) and mud dominated bioclastic packstone of the Calcarenite di Gravina formation, the pore network involves intragranular pores and, subordinately, mouldic and vug pores. Despite these lithofacies are mainly characterized by sand fine grain size and pore structure with non-negligible tailing fine content, it is possible to assert that open porosity (interconnected and accessible pores) provides an important contribution to the total porosity, while closed porosity is very low or absent due to scarce post-depositional cementation, as demonstrated by imbibition test results. In particular, the most widespread and known lithofacies belonging to the Pietra Leccese formation, although characterized by the presence of many intragranular pores consisting of internal chambers of foraminifera, show open porosity slightly lower or equal to total porosity. The overall interconnection of the pore network is due to intercrystal pores and microcracks. The last take place during burial diagenetic phases, mostly in the intergranular spar cement. Figure 5, a provides the results of an experimental imbibition test, suggested to complement the standard test method according to ASTM D2216-19, for an immersed sample of mud-dominated bioclastic packstone from Massafra, in the locality of Caprocetta (Apulia).

Fig.4. Macroscopic (a) and microscopic (b) appearances (microphotographs in plane-polarized light) of the medium-grained calcarenite of Montescaglioso, Bongermino quarry, Basilicata

Fig.5. Relationship between degree of saturation and time found by means of imbibition tests for water-immersed specimens of calcarenite (a); stress-strain curves from servo-controlled uniaxial compression test on two samples (b); samples belonging to the Calcarenite di Gravina formation, Caprocetta locality, Massafra, Apulia

1 – sample in dry condition; 2 – sample in saturated condition

A degree of saturation of 88 % is obtained for this immersed sample at the pressure exerted only by buoyancy forces, but the absorption of further water by immersion under vacuum conditions (80 kPa) leads to full saturation (Sr = 100 %), as demonstration of a total interconnection and accessibility of the pores. Furthermore, at the pressure exerted only by buoyancy forces, for the specimen tested most of the water is absorbed in a few minutes (68 % in about 2 min), following which water absorption increases very slowly.

Other calcarenite lithofacies also showed similar trends. Many previous studies, by means of liquid intrusion (e.g., MIP) combined with or separate other methods such as image analysis and IFU (Intermingled Fractal Units) or X-ray Micro-computer Tomography (MCT) and Infrared Thermo-graphy (IRT), to mention only a few [1, 2, 7, 24, 25], demonstrated how porosity is significantly or completely open for these materials. Closed pores can only be formed mainly by recrystallization processes which strongly modify the fabric of these materials due to prolonged diagenesis, resulting in an increase of stiffness and strength. Recently, an interesting approach is presented in Ciantia et al. [7], where the authors used different calcarenite lithofacies from some exploitation sites in Apulia to reconstruct their three-dimensional textures by means of MIP, SEM and X-ray MCT.

Pore structure and tortuous nature of pore channels are responsible of the capacity of the calca-renites to retain and transmit water or other fluids, and to conduct, propagate and accumulate heat in both saturated and unsaturated conditions. At the mesoscopic scale, in fact, porosity of the calca-renites is basically primary in type, being controlled by the texture; the structural porosity is limited to the synsedimentary and post-depositional structures, including laminations, bioturbations and microcracks. A theoretical framework which can be used to investigate the unsaturated hydraulic behaviour of the calcarenite rocks is based on the pore bundle model and dual porosity concept under equilibrium conditions in the falling head infiltration test, by using the advective-diffusive forms of the Richards’ equation [6].

At the rock mass scale, both the primary and secondary porosity can play an important role in defining the total porosity. Thus, two types of porosity have to be considered – textural and structural. The textural porosity depending on nature (bioclast species type, lithoclasts etc.), arrangement and interlocking of grains; the structural porosity is related to the macroscopic non-random discontinuities, e.g. karst features, fractures and faults. With the exception of some coarse-grained calcarenite lithofacies which show high values of water hydraulic conductivity, the most widespread lithofacies outcropping in Apulia and Basilicata show a moderate water permeability. In carbonate pore systems, commonly, pore type effectiveness and complex pore size networks can explain a low correlation between porosity and permeability.

For the calcarenites of Apulia and Basilicata, at the laboratory scale, the hydraulic conductivity is influenced largely by amount and type of cement, and pore-size distribution, which in turn depends on the grain-size distribution, grain shape and rock fabric. In other words, the smaller the grains are, the smaller the average size of the pores and the lower the hydraulic conductivity. Thus, the calcarenites of Apulia and Basilicata are mainly characterized by open pore networks and permeability is not dependent on the relationship between closed and open porosity, but it is conditioned by their fabric, including relationships between lithoclasts and bioclasts, taxonomic groups and primary mine-ralogy of bioclasts, and type and distribution of micrite and cement. In more detail, mud-dominated bioclastic packstone and bioclastic wackestone of the Plio-Quaternary calcarenites are characterized by lower hydraulic conductivity with respect to grainstone and packstone lithofacies, mainly due to a wide distribution of pores (bimodal and exceptionally trimodal) which includes relatively long tails of large and medium capillary pores, sensu Mindess et al. [20]. Specifically, they are open intercrystalline pores within micrite and cement, not resolvable or hardly observable at the resolution of an optical microscope commonly used for thin section inspections. Therefore, for the calcarenites of Apulia and Basilicata, a greater or lesser hydraulic conductivity obtained from laboratory direct mea-surements on the different lithofacies should not be explained by the distinct and diverse weight in the assessment of closed and open porosity, but it is greatly dependent on the relationship between capillary pores and air pores. In other words, the hydraulic conductivity is higher for the lithofacies in which coarse tails of non-capillary pores (slowly draining pores and rapidly draining pores) are present in the pore distribution curves; conversely, the hydraulic conductivity is lower for the lithofacies with long tails of capillary pores [6].

The remarkable presence of capillary pores (intragranular and intercrystal pores), in the calcarenite lithofacies belonging to the Pietra Leccese formation, justifies lower values of hydraulic conductivity than those of the main lithofacies of the Plio-Quaternary calcarenites, although both the geological formations are characterized by open porosity. In more details, for the lithofacies of the Pietra Leccese formation, the capacity to transmit fluids through their pore network depends on grain packing, grain-size distribution, including grain-cement sizes, which in turn affect the pore-size distribution of these rocks.

Total porosity and porosity type also affect thermal properties of these materials: capacity to conduct, propagate and accumulate heat is low and this is more evident for the Plio-Quaternary facies (Calcarenite di Gravina) with respect to the Miocene facies (Pietra Leccese). Overall, thermal conductivity and thermal diffusivity of the dry calcarenites are primarily governed by porosity: they decrease as porosity increases and degree of packing decreases. In particular, no remarkable direct influence of grain- and pore-size on the thermal properties is generally observed. On the contrary, at a higher degree of cementation can be associated slightly higher values of the above-mentioned thermal properties. The effective role of the open porosity and closed porosity on the thermal properties of these materials still remains to be sorted out, although the thermal conductivity and thermal diffusivity of calcarenites characterized by pore structure containing also closed pores should be greater than those of calcarenites with open pore structure, all other things being equal. To date, no study has investigated this issue for the calcarenites from Apulia and Basilicata, since the porosity for these materials is essentially open, as already widely demonstrated in the specific literature. Additionally, an increase in the thermal conductivity and a decrease in the thermal diffusivity are found in all the lithofacies with the increase in water content. Thus, porosity being equal, thermal conductivity and specific heat capacity increase and thermal diffusivity decrease in water-saturated conditions. Aesthetic appeal and insulating properties still make these materials highly appreciated for building and construction purposes today.

Mechanical properties. According to the engineering classification of rocks based on UCS and elastic modulus of intact laboratory samples elaborated by Deere and Miller [26], the main calcarenite lithofacies from Apulia and Basilicata fall into very low strength class. They can be considered as soft rocks on the basis of the UCS at the dry conditions, generally less than 25 MPa. On average the Pietra Leccese formation shows higher values of UCS than those of the Calcarenite di Gravina formation due to higher packing density, wider distribution of calcite cement, sparry calcite in particular (although smaller in size, microspar). A positive correlation between dry density or grain packing and UCS is not always confirmed for the Calcarenite di Gravina formation. Generally, type and amount of calcite cement control the overall strength of this material, but it is difficult to quantify the contribution of each fabric element on this regard. Based on direct experiences described in previous papers, already cited in this work, mud-dominated packstone and fine- to medium-grained bioclastic wackestone with abundant microspar, and the medium or coarse grained lithofacies with drusy, granular or blocky cement present the highest UCS and ITS values.

At the rock mass scale, a complex time-dependent and spatially variable physical mechanical behaviour is associated in particular to coarse grained lithofacies due to the heterogeneous spatial distribution of cement, significantly more abundant in the upper levels of the outcrops. With the particular regards to the Calcarenite di Gravina formation, the most important calcarenite types for their historical use as ornamental and building stone are medium or medium-fine grained packstone or grainstone characterized at the dry state by UCS in the range 3-7 MPa and UCS/ITS between 7.5 and 9.0, the latter, generally, limited to the more resistant types [2, 9]. Stress – strain curves describe a brittle material and exhibit essentially linear and elastic behaviour up to the yielding point, which marks the start of a progressive rupture mechanism of the cement bonds and, volumetric compression strain becomes nonlinear and it is usually plastic [2].

The yield point is not always well-defined, especially when the early portion of the curve deviates from linear proportionality and the curve’s slope changes due to irregular distribution of cement and small partial failures in the specimens. After the yield point the slope of the curve decreases until a well-defined peak is reached and then strain softening occurs (Fig.5, b). The nature of each curve is profoundly influenced by cementation which overcomes the effect of other fabric elements. Specimens showing regular distribution of cement and fabric homogeneity are characterized by an extensional failure surface, propagating in the direction of the maximum load application line. Tortuous or irregular failure surfaces or two or three intersecting failure surfaces can be attributed to the anisotropy of specimens due to clusters of higher grain packing or cementation rate.

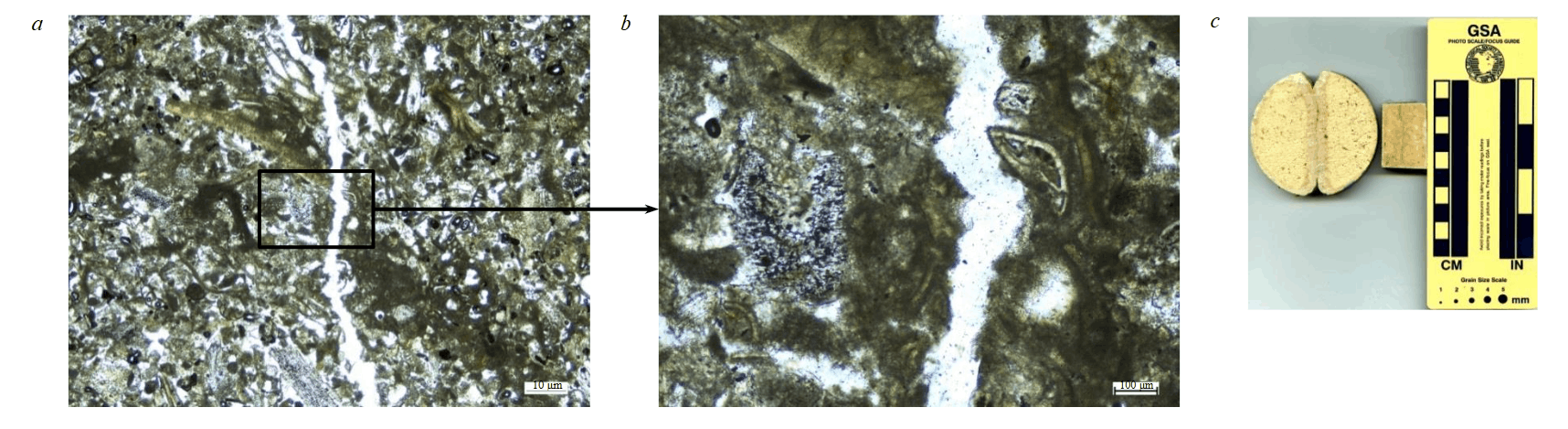

Generally, the failure surfaces run through the pore space involving the cement without intersecting grains, despite the presence of delicate shells (Fig.6). The crack propagation is not transgranular (between the grains or along the grain boundaries) but involves shells in the facies with abundant late generation cement. It is of particular importance to note the impact of water content on the mechanical behaviour of these rocks because with the increasing of degree of saturation the calcarenite strength, in terms of UCS and ITS, decreases significantly, up to a reduction higher than 45 % under saturated conditions (Sr = 100 %), with respect to the dry material [2, 7]. Thus, the presence of water in the pores and capacity to hold water in the pore network, the last directly related to pore-size distribution, strongly affect the mechanical behaviour of these materials, with strength and stiffness that considerably decrease in the transition from dry to saturated conditions (see Fig.5, b). Furthermore, the lightly cemented calcarenites are very interesting in terms of mechanical properties because they exhibit brittle deformation in the dry state and, ductile or pseudo-ductile deformation and higher decrease of UCS or ITS for saturated samples. These are characterized by the presence of only early calcite cement and a wide pore-size distribution, comprising capillary and non-capillary pores because open porosity and pore-size distribution influence the water absorption and retention of these rocks. Thus, type and amount of cement and presence of water in pores mainly affect the mechanical behavior of the calcarenites [2, 7].

Fig.6. Different views of a failure plane of a calcarenite specimen belonging to the Plio-Quaternary calcarenites (Papapietro quarry, Montescaglioso, Basilicata): a – thin section microphotograph in plane-polarized light (2x); b – magnification at 10x of the microphotograph frame (delicate shells are unbroken along the failure plane); c – slice of the indirect tensile strength test specimen and polished slab used for the thin section from the same piece

Fine-grained lithofacies are able to hold water during the UCS and ITS tests maintaining a high degree of saturation. Coarse- and medium-grained facies, on the other hand, may suddenly leak water during the UCS or ITS tests, especially when they are characterized by great percentages of interconnecting meso- and macropores, and high hydraulic conductivity values. Thus, the incidence of water on the mechanical properties of these lithofacies is lesser than that in the other.

Ciantia et al. [7] aptly explained and demonstrated, by means of a series of new and non-codified tests, the different mechanisms of debonding for short- and long-term immersion in water. Their study demonstrates that the hydro-chemo-mechanical weakening of calcarenites is linked to both temporary (synsedimentary cement) and persistent (diagenetic cement) bonding. They state that saturation for calcarenite specimens does not cause any short-term effect on the diagenetic cement. This leads to three important considerations. First, a strong weakening of the material for short-term immersion in water, a typical situation that occurs during laboratory mechanical tests, characterizes only the facies in which there is almost exclusively first-generation cement. Second, for calcarenite rock masses, we must also consider the effects of the chemical dissolution of the diagenetic cement for long-term immersion in water, a mechanism which accelerates creep rate and damage evolution. And finally, the long-term chemical dissolution of calcite cement is the main mechanism affecting the mechanical behaviour of the calcarenites.

With regard to the Oligo-Miocene lithofacies, generally, they show lower total porosity, lower permeability and higher overall strength than those of Plio-Quaternary lithofacies. Good packing density and wider distribution of calcite cement, microspar in particular, characterize these lithofacies, but also for these materials, a positive correlation between UCS or ITS and dry density or grain packing is not always verified. It follows that, the main factors affecting the physical and mechanical properties of these materials are the amount and type of cement and pore-size distribution. Worth mentioning is the Piromafo facies, a greenish-brown or greenish-gray fine- to medium-grained glauconitic and phosphatic biomicrite with macrofossils, especially Bivalves and Gastropods, occurring in the upper part of the Pietra Leccese formation. The Piromafo facies shows a lower capability to conduct and propagate heat and higher fire resistance with respect to other lithofacies of the Pietra Leccese and this feature can be attributable to the chemical and mineralogical composition of the material in its insoluble residue content rather than to the differences of porosity or pore network topology and pore-size distribution.

A concluding observation is the greater dispersion in the values of uniaxial compressive strength and tensile strength in the Calcarenite di Gravina formation compared to Pietra Leccese. Calcarenite di Gravina is, in fact, an extremely heterogeneous formation in terms of textural and microstructural features. It includes both high-energy temperate-water bioclastic and mixed bioclastic-lithoclastic calcarenites from shore, nearshore, and offshore zones, in response to high-frequency sea level changes. In particular, the lithoclasts derive from the Cretaceous limestone bedrock and were supplied to the shoreline via ephemeral rivers. In contrast, the Pietra Leccese formation is a homogeneous planktonic foraminiferal biomicrite, typically deposited in shallow marine environments.

Based on the above considerations and critical review of data reported in the relevant scientific literature, and personal previous experiences on the subject, it is possible to propose a new geotechnical classification of the calcarenites using the values of UCS in the dry condition, fabric description and cementation grade, and stress – strain behaviour of the material in the dry and saturated conditions (Table 2). In particular, the stress – strain behaviour of the calcarenites from Apulia and Basilicata was obtained in the framework of a cooperation project involving researchers and technicians of the University of Bari Aldo Moro and the National Research Council (CNR)-IRPI Department of Bari. In the last decade, as a part of this research activity, 484 samples belonging to the main lithofacies of the calcarenites from Apulia and Basilicata were classified by means of petrophysical and mechanical test at the geotechnical laboratory of the University of Bari and geotechnical and geomechanical laboratory of CNR-IRPI Bari. In addition to the fabric analysis, UCS and ITS tests in the dry and saturated state were performed for each facies by setting the vertical displacement rate at 1.0 μm/s which was measured by means of displacement transducers, whereas the axial stress was measured by means of a load cell. The most important class limit is that between very soft and soft calcarenites because it is marked by the UCS value in the dry state of 5 MPa. In fact, under this value, the calcarenites exhibit brittle behavior in the dry state and pseudo-ductile or ductile behavior in the saturated state. Furthermore, over this value the calcarenites show similar stress – strain behavior in both dry and saturated conditions, although the value of UCS in saturated conditions is considerably lower than that determined in dry conditions. In reasonable terms, the overall strength of the calcarenites is mainly controlled by type and amount of calcite cement, water content or degree of saturation and pore size distribution for which it would be useful to address statistically the spatial trends of the dependent random variable due to one or more independent random variables. Thus, new studies and research on the behaviour of these materials could develop in this direction.

Weathering and durability. All other factors being equal, overall strength and pore structure have the most significant impact on rock weathering as well as stone durability. With respect to strength, a fundamental role is played by the tensile strength, which represents the “cohesive” strength of materials and is comparable with the crystallization pressure. Besides, the tensile strength is closely related to the rock fabric features and, especially for litho- and/or bioclastic carbonate materials, can be considered as direct expression of the amount, type and distribution of cement. The most dangerous weathering processes in calcarenites develop in the presence of water, such as freezing/thawing, salt crystallization but also material dissolution and biodeterioration [9, 24, 27].

Furthermore, these processes depend on water infiltration rate, hydrodynamic properties of water movement, water absorption and retention. We also have to consider that all three phases of water (vapor, liquid and ice) can be found within the pore space. Thus, the analysis and characterization of the interaction between rock and water play a fundamental role in clarifying and defining causes of rock weathering or stone deterioration and decay patterns.

Table 2

Classification of calcarenites from Apulia and Basilicata

|

Group |

Range of UCS in the dry state, МPа |

General rating of rock based on strength |

Rock fabric features |

Stress – strain behaviour |

|

AC1 |

10-25 |

Moderately soft |

Coarse- and medium-grained packstone and grainstone, mud-dominated packstone; partial and total void-filling drusy and granular cement; tangent and long contacts between grains. Fine- to medium-grained bioclastic wackestone and mud-dominated packstone with the predominance of sparry cement |

Brittle under different water conditions |

|

AC2 |

5.0-10 |

Soft |

Medium-grained grainstone and packstone; partial void-filling and pore-lining “dog tooth” cement; tangent and long contacts between grains |

Brittle under dry condition, brittle or quasi-brittle in saturated condition |

|

AC3 |

1.0-5.0 |

Very soft |

Coarse-grained grainstone, medium-grained packstone; scarce cement, meniscus and microcrystalline in types; tangent contacts between grains; medium-fine wackestone with a crypto- and/or microcrystalline based mass |

Brittle under dry condition, ductile or pseudo-ductile in saturated condition |

|

AC4 |

0.6-1.0 |

Extremely soft |

Coarse grainstone and medium packstone very scarce in cement, microcrystalline in type; microsparstone as a result of complete obliterative recrystallization or replacement; fine wackestone and packstone with irregular distribution of fibrous acicular cement and/or discontinuous epitaxial fringes; floating and tangent contacts between grains |

Brittle or quasi-brittle under dry condition, ductile in saturated condition |

In this contest, the pore structure, in terms of pore-size distribution, geometry and topology of the pore network, represents the main critical factor regarding the potential for the calcarenite rock to absorb and hold water and hence to weather. In particular, hydraulic conductivity and specific surface area are respectively in direct and inverse relation with pore size. In turn, water condensation and retention inside the rocks is directly related to specific surface area. It was observed in my laboratory studies at the sample scale that wide pore size distributions comprising strong coarse and fine tails can be considered an important factor in evaluating weatherability of the calcarenites: materials characterize by pore networks with coarse pores (up to 2.0 mm) connected to a significant number of pores lower than 10 μm are the most susceptible to dissolution and crystallization weathering. It is not without reason that crystallization pressure is inversely related to pore size. Thus, coarse pores enable the entry of water into material, while capillary pores hold water against drainage forces. The longer the water stays in a material the greater the possibility that it may cause weathering. Furthermore, the calcarenite tensile strength is connected with cement bonding properties, thus irregularly and weakly cemented lithofacies with early cement fringes only, as a fine encrustation of minute calcite crystals growing at the contact between grains or on the pore wall surfaces, are particularly susceptible to physical weathering. In other words, sizes and connectivity of pores type and amount of cement as well affect, on the one hand, the hydraulic behaviour of the calcarenites in terms of sorptivity, hygroscopicity, water absorption and retention, and on the other hand, tensile strength. Detailed information about pore structure and cementation can be therefore considered essential for a qualitative evaluation of the potential weatherability for the calcarenites.

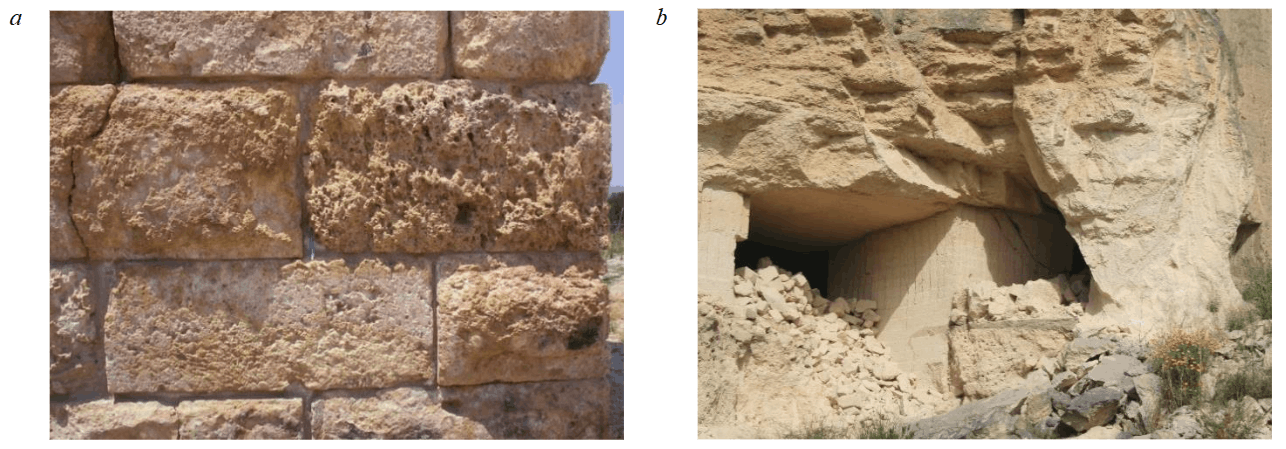

In monuments and buildings built with calcarenite stones, deterioration states of the ashlar blocks are also dependent on their position as regards exposure in architectural structures. The appearance of stone surfaces is in fact the result of their exposure to wind, rain, humidity and thermal cycling effects. In this regard, it is useful to remember that calcite is the only mineral that upon heating expands in one direction while contracts in the other and upon cooling it contracts along the c-axis while expands along the other ones. All this results in induced tensile, compressive and shear stresses at the grain boundaries and causes microcracks which increase porosity and whose coalescence can lead to the failure of the blocks. In many archaeological sites, it is not so uncommon to observe fractures, crossing the ashlar blocks as a result of long-term overloading and creep (Fig.7, a).

Typical decay patterns in the ashlar blocks of calcarenite consist of loss of material and detachment, including granular disintegration into sand, breakout of compact stone fragments and notching, differential erosion associated to lamination, bioturbation, alveolization, commonly attributed to salt crystallization, lichen crusts and other biodeterioration effects. Particularly interesting in calcarenite rocks is the time effect on the strength and stiffness properties at the rock mass scale (i.e., creep). Calcarenites are very often subject to deterioration processes causing a progressive degradation of their mechanical properties. In many sites, these processes can cause the collapse of cliffs or underground cavities, with dangerous consequences also in terms of loss of human life. Experiences from underground calcarenite quarries have shown that the stability degree of pillars and vaults within the quarries decreases with time, as an effect of creep on the total strength of the rock mass [28]. This effect is particularly significant in humid or wet sites, and for soft rock mass subjected to hydro and thermal cycling (Fig.7, b).

Fig.7. Fractures, alveolar forms and microbial patinas on rectangular blocks of an ancient wall (а); progressive roof failures, and pillar and wall crushing found in the underground quarries (b), Pietra Caduta locality, Canosa di Puglia, Apulia

Conclusions

This paper addresses the fundamental aspects of the physical and mechanical behavior of calcarenite rocks, through new tests and a comparison of results with those available in the literature. A laboratory analysis was conducted on different calcarenite lithofacies from Apulia and Basilicata. The method adopted in this study to describe the petrophysical and mechanical properties of these materials includes conventional and non-conventional geotechnical laboratory testing procedures, thin section petrography, and an in-depth analysis of bibliographic data on these materials. The literature data also include results from studies that employed combined techniques, such as liquid intrusion (MIP), image analysis, Intermingled Fractal Units (IFU), X-ray Micro-computed Tomography (MCT), and Infrared Thermography (IRT), among others.

The physical-mechanical behaviour of carbonate soft rocks is a complex topic but, at the same time, very fascinating because the factors involved are different and the relationships between them are intricate and, at times, not entirely clear.

In the Mediterranean Basin, including parts of South Italy, calcarenite sequences crop out along hill slopes, sea or valley cliffs and quarry walls. These rocks are mainly massive bedded or medium-bedded and display significant textural and structural variability due to complex depositional processes and post-depositional diagenesis, influenced by the underlying bedrock topography. Consequently, different lithofacies with distinct grain- and pore-size distributions, pore network topologies, and bonding characteristics can be found within the same sedimentary body.

Recent research on petrophysical and mechanical properties of calcarenites has provided a more complete understanding of their behaviour under different boundary conditions and degree of saturation. Current findings indicate that the complex physical-mechanical behaviour of calcarenites is controlled by fabric, including texture and structure both microscopic and macroscopic. Specifically, type and amount of cement and pore-size distribution, which are closely associated to the distribution of grain sizes, grain shape, compaction and other processes such as dissolution and recrystallization, play a fundamental role both in determining the stress – strain behaviour and the hydraulic properties of the material.

The intricate pore network of calcarenites is due to small-scale lithofacies heterogeneities which lead to the co-presence of both micropores and macropores, highlighted by a bimodal and occasionally trimodal pore size distribution. For the calcarenites from Apulia and Basilicata, this complexity of pore structure is associated with a predominantly open porosity because all pores are connected by very small capillary-like paths known as pore throats, as demonstrated by 2D and 3D metho-dological approaches and simple vacuum imbibition tests. Exceptions occur due to vadose blocky low-Mg calcite cements that occlude pores in the caliche and rudstone intervals. Petrographic analysis with an optical microscope, limited to a resolution of 0.2 μm, cannot resolve details on pore structure, such as pore throats and microcracks, which are crucial for understanding pore interconnectivity. More information on the subject together with other physical and mechanical properties of the calcarenites can be obtained combining qualitative results from 2D thin section study and 3D methods (quantitative 3D petrography, porosimetry etc.), adequately compared with geotechnical test data.

The complex and tortuous pore networks in some calcarenite lithofacies explain the low correlation between permeability and porosity, as fluid transmission capacity depends on the pore structure. Specifically, bimodal, and occasionally trimodal, pore-size distributions, which include large and medium capillary pores combined with entrained air pores, certainly affect the hydraulic properties of the material but at the same time hinder the fundamental understanding of drainage processes. In other words, porosity being equal, the hydraulic properties of each calcarenite lithofacies strongly depend on the geometry and topology of the pore network and the relative percentages of pores present, that is, between capillary pores that hold water against drainage forces and coarse pores where free gravity drainage occurs. Furthermore, in calcarenites, depositional porosity undergoes changes due to diagenetic processes after burial, through the formation of later cement and post-depositional dissolution. In general, second-generation cements, such as drusy, granular, or blocky and equant mosaic, reduce porosity and permeability by altering the pore structure, particularly the pore-size distribution and network connectivity. These changes affect water infiltration, with hydraulic behavior in terms of hygroscopicity, sorptivity, water absorption, and retention being tightly controlled by pore structure and the type and amount of calcite cement. These properties and tensile strength, also controlled by the type and amount of calcite cement, provide a qualitative evaluation of the potential weatherability for the calcarenites.

Another important aspect to consider is the impact of water content and degree of saturation on the mechanical behavior of these materials. Most calcarenites show a decrease in UCS and tensile strength by over 45 % compared to the dry material when saturated. Additionally, lightly cemented calcarenites, with only early diagenetic cement, exhibit changes in stress – strain behavior and stiffness when transitioning from dry to saturated conditions, with the mode of failure shifting from brittle fracturing to pseudo-ductile or ductile fracturing.

The selective deterioration patterns observed on exposed calcarenite stone blocks result from complex chemical, physical, and biological processes. These processes vary spatially and temporally within the same artifact due to factors such as solar exposure, humidity, and intrinsic material characteristics, in terms of microfabric and mesoscopic structures. While the main weathering agents can be identified within a given environmental context, predicting their specific effects on stone material and hypothesizing about its durability and deterioration rate is challenging. At the same time, it is not always easy to associate each physical, chemical, or biological process with different decay patterns or to define with certainty the impact of each agent or factor in the evolution of the overall degradation process. This is because the genesis and development of decay patterns are strongly controlled by the depositional and diagenetic fabric of the stone material. The relationship between certain inorganic and organic sedimentary structures (e.g., parallel and cross-lamination, bioturbation) and decay patterns is evident through differential erosion processes.

While significant progress has been made in understanding the physical and mechanical behavior of calcarenites, much remains to be explored regarding the complex relationships between their textural and structural characteristics and the performance of these materials across various application contexts. Future research should aim to investigate these interactions further, particularly in relation to hydrogeology, such as groundwater filtration and infiltration processes, as well as their role in construction geology, and the stability of underground spaces and slopes. In addition to their historical use as natural building materials in iconic Mediterranean structures, calcarenites continue to play an important role in modern construction practices. A comprehensive approach that integrates geological, structural, and environmental factors will be crucial for advancing both the preservation of cultural heritage and the development of sustainable solutions in geoengineering.

References

- Ciantia M.O., Castellanza R., Crosta G.B., Hueckel T. Effects of mineral suspension and dissolution on strength and compressibility of soft carbonate rocks // Engineering Geology. 2015. Vol. 184. P. 1-18. DOI: 10.1016/j.enggeo.2014.10.024

- Lollino P., Andriani G.F. Role of Brittle Behaviour of Soft Calcarenites Under Low Confinement: Laboratory Observations and Numerical Investigation // Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering. 2017. Vol. 50. Iss. 7. P. 1863-1882. DOI: 10.1007/s00603-017-1188-0

- Zimbardo M. Mechanical behaviour of Palermo and Marsala calcarenites (Sicily), Italy // Engineering Geology. 2016. Vol. 210. P. 57-69. DOI: 10.1016/j.enggeo.2016.06.004

- Noël C., Fryer B., Baud P., Violay M. Water weakening and the compressive brittle strength of carbonates: Influence of fracture toughness and static friction // International Journal of Rock Mechanics and Mining Sciences. 2024. Vol. 177. № 105736. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijrmms.2024.105736

- Kanji M.A. Critical issues in soft rocks // Journal of Rock Mechanics and Geotechnical Engineering. 2014. Vol. 6. Iss. 3. P. 186-195. DOI: 10.1016/j.jrmge.2014.04.002

- Pastore N., Andriani G.F., Cherubini C. et al. Pore network model to predict flow processes in unsaturated calcarenites // Italian Journal of Engineering Geology and Environment. 2024. Special Issue 1. P. 261-273. DOI: 10.4408/IJEGE.2024-01.S-29

- Ciantia M.O., Castellanza R., di Prisco C. Experimental Study on the Water-Induced Weakening of Calcarenites // Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering. 2015. Vol. 48. Iss. 2. P. 441-461. DOI: 10.1007/s00603-014-0603-z

- Festa V., Fiore A., Luisi M. et al. Petrographic features influencing basic geotechnical parameters of carbonate soft rocks from Apulia (southern Italy) // Engineering Geology. 2018. Vol. 233. P. 76-97. DOI: 10.1016/j.enggeo.2017.12.009

- Andriani G.F. Comment on «Petrographic features influencing basic geotechnical parameters of carbonate soft rocks from Apulia (southern Italy)» [Eng. Geol. 233: 76-97] // Engineering Geology. 2021. Vol. 285. № 106053. DOI: 10.1016/j.enggeo.2021.106053

- Bonomo A.E., Munnecke A., Schulbert C., Prosser G. Microfacies analysis and 3D reconstruction of bioturbated sediments in the calcarenite di Gravina formation (southern Italy) // Marine and Petroleum Geology. 2021. Vol. 125. № 104870. DOI: 10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2020.104870

- Margiotta S., Sansò P. The Geological Heritage of Otranto – Leuca Coast (Salento, Italy) // Geoheritage. 2014. Vol. 6. Iss. 4. P. 305-316. DOI: 10.1007/s12371-014-0126-8

- Calia A., Tabasso M.L., Mecchi A.M., Quarta G. The study of stone for conservation purposes: Lecce stone (southern Italy) // Stone in Historic Buildings: Characterization and Performance. Geological Society of London, 2014. Vol. 391. P. 139-156. DOI: 10.1144/SP391.8

- Romanazzi A., Gentile F., Polemio M. Modelling and management of a Mediterranean karstic coastal aquifer under the effects of seawater intrusion and climate change // Environmental Earth Sciences. 2015. Vol. 74. Iss. 1. P. 115-128. DOI: 10.1007/s12665-015-4423-6

- Balacco G., Alfio M.R., Parisi A. et al. Application of short time series analysis for the hydrodynamic characterization of a coastal karst aquifer: the Salento aquifer (Southern Italy) // Journal of Hydroinformatics. 2022. Vol. 24. Iss 2. P. 420-443. DOI: 10.2166/hydro.2022.135

- Zhilei He, Guoli Wu, Jun Zhu. Mechanical properties of rock under uniaxial compression tests of different control modes and loading rates // Scientific Reports. 2024. Vol. 14. № 2164. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-024-52631-1

- Aydin A. ISRM Suggested Method for Determination of the Schmidt Hammer Rebound Hardness: Revised Version // The ISRM Suggested Methods for Rock Characterization, Testing and Monitoring: 2007-2014. Springer, 2015. P. 25-33. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-07713-0_2

- Popov Y., Beardsmore G., Clauser C., Roy S. ISRM Suggested Methods for Determining Thermal Properties of Rocks from Laboratory Tests at Atmospheric Pressure // Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering. 2016. Vol. 49. Iss. 10. P. 4179-4207. DOI: 10.1007/s00603-016-1070-5

- Mongelli F., Loddo M., Tramacere A. Thermal conductivity, diffusivity and specific heat variation of some Travale field (Tuscany) rocks versus temperature // Tectonophysics. 1982. Vol. 83. Iss. 1-2. P. 33-43. DOI: 10.1016/0040-1951(82)90005-1

- Lokier S.W., Al Junaibi M. The petrographic description of carbonate facies: are we all speaking the same language? // Sedimentology. 2016. Vol. 63. Iss. 7. P. 1843-1885. DOI: 10.1111/sed.12293

- Karagiannis N., Karoglou M., Bakolas A., Moropoulou A. Building Materials Capillary Rise Coefficient: Concepts, Determination and Parameters Involved // New Approaches to Building Pathology and Durability. Springer, 2016. P. 27-44. DOI: 10.1007/978-981-10-0648-7_2

- Dasgupta T., Mukherjee S. Porosity in Carbonates // Sediment Compaction and Applications in Petroleum Geoscience. Springer, 2020. P. 9-18. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-030-13442-6_2

- El Sharawy M.S., Gaafar G.R. Pore – Throat size distribution indices and their relationships with the petrophysical properties of conventional and unconventional clastic reservoirs // Marine and Petroleum Geology. 2019. Vol. 99. P. 122-134. DOI: 10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2018.10.006

- Nash D.J. Calcretes, Silcretes and Intergrade Duricrusts // Landscapes and Landforms of Botswana. Springer, 2022. P. 223-246. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-030-86102-5_13

- Pia G., Casnedi L., Sanna U. Pore Size Distribution Influence on Suction Properties of Calcareous Stones in Cultural Heritage: Experimental Data and Model Predictions // Advances in Materials Science and Engineering. 2016. Vol. 2016. № 7853156. DOI: 10.1155/2016/7853156

- Mineo S., Pappalardo G. InfraRed Thermography presented as an innovative and non-destructive solution to quantify rock porosity in laboratory // International Journal of Rock Mechanics and Mining Sciences. 2019. Vol. 115. P. 99-110. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijrmms.2019.01.012

- Tatone B.S.A., Abdelaziz A., Grasselli G. Novel Mechanical Classification Method of Rock Based on the Uniaxial Compressive Strength and Brazilian Disc Strength // Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering. 2022. Vol. 55. Iss. 4. P. 2503-2507. DOI: 10.1007/s00603-021-02759-7

- Hemeda S. Influences of bulk structure of Calcarenitic rocks on water storage and transfer in order to assess durability and climate change impact // Heritage Science. 2023. Vol. 11. № 118. DOI: 10.1186/s40494-023-00949-w

- Paraskevopoulou C. Time-Dependent Behavior of Rock Materials // Engineering Geology. IntechOpen, 2021. 33 p. DOI: 10.5772/intechopen.96997