Ontological modeling and management of digital transformation of mining enterprises architecture

- 1 — Head of Laboratory National University of Science and Technology “MISiS” ▪ Orcid

- 2 — Ph.D., Dr.Sci. Head of Department National University of Science and Technology “MISiS” ▪ Orcid ▪ Scopus ▪ ResearcherID

Abstract

The paper is devoted to the conceptual formalization of the goals, objectives and criteria for managing the digital transformation of mining enterprises. The main idea is to define digital transformation as a process of minimizing or completely excluding human participation from the implementation of production processes in order to build an autonomously functioning cyber-physical industrial system. In order to determine the ways of building and functioning mechanisms of such systems, the necessity of forming an enterprise architecture model has been established, both ensuring the completeness and consistency of the knowledge embedded in it, and providing an instrumental numerical basis for self-organization and self-regulation of the system. The irrelevance of applying existing standards and frameworks for building architecture models is substantiated. Approaches to the construction of an ontological model and ways of its application in the management task of the digital transformation of mining enterprises are proposed. Under the results of the work, a basic ontological model of the mining enterprise architecture was formed based on the OWL descriptive logic language in the Protégé environment, applicable to geospatial natural and technical industrial systems with an open type of production environments. The resulting model was tested using the HermiT logical inference mechanism, confirmed its coherence and consistency, which indicates the potential correctness of the initial hypotheses of the study and the possibility of further research into the formation of a methodology for the digital transformation of mining enterprises.

Introduction

Today, most industrial enterprises, with the support of engineering companies and research groups, are actively working in the field of digital transformation (DT) of production systems in the paradigm of the Industry 4.0 concept [1-3]. This activity includes:

- development, implementation, and pilot testing of robotic complexes with various levels of autonomy, including the use of unmanned aerial vehicles, unmanned transport systems and technological equipment [4-6];

- application of machine learning and data mining methods for a wide range of production mana-gement tasks [7-9] (predictive maintenance [10-12], planning of production indicators [13, 14], etc.);

- the organization of efficient transmission, storage and processing of large amounts of data [15, 16], coming from Internet of Things devices into a distributed computing environment [17, 18].

A relatively new direction is the work in the field of creating digital twins of technological processes and equipment, which are a highly accurate cybernetic model with two-way control communication with a physical analogue [19, 20].

Despite the success in solving certain scientific and practical tasks, the issues of conceptual goal-setting of such activities remain an obvious and critically important problem on the way to scaling the results and, in fact, the actual digital transformation of enterprises. At the declarative level, the result of digital transformation is understood as a transition to qualitatively new principles for the implementation of technological processes, which is difficult to formalize and quantify. Taking into account that automation is the previous stage of enterprise transformation, it should be assumed that the goal of digitalization can be formulated as minimizing or completely excluding (where possible) human participation in production processes through the use of Industry 4.0 methods and technologies. This means that the processes currently being implemented with direct human participation, including through information and automated systems, should be brought to an autonomously executable (software) form of management. Thus, the ultimate goal of digital transformation of enterprises is to build an effective autonomously functioning cyber-physical industrial system.

Based on goal-setting, it can be assumed that an autonomously functioning system, like some complexly configured rational agent [20-22], should have the ability to self-organize and self-regulate, and in some cases, to self-learn. In this regard, it is obvious that ensuring such requirements is possible only if the system has objective knowledge of its own functionality, criteria, and limitations of activity, as well as the structure and condition of its components. Such knowledge about the system is commonly referred to as an “architecture model” [23-25], and currently there are several international standards and frameworks regulating this concept with varying degrees of detail and practical applicability. The most relevant are the IEC PAS 63088:2017 “Smart manufacturing – Reference architecture model Industry 4.0 (RAMI4.0)” [26, 27] and the framework “The Open Group Architecture Framework 10 (TOGAF 10)” [28, 29]. Both standards specify the need for declarative knowledge in the form of an ontological (meta-) architecture models to reduce errors in managing the progress of the digital transformation of the enterprise. However, despite a number of really important methodological aspects, the proposed models cannot be directly used for the digital transformation of mining industries, do not regulate the construction of an autonomously functioning industrial system and, as a result, do not have the necessary tool base for formal computational procedures of knowledge manipulation. The purpose of the work is to formalize the type and mechanisms of the architecture model of an autonomously functioning cyber-physical industrial system to ensure the processes of digital transformation of mining enterprises.

Models and methods of the study

RAMI4.0 and TOGAF 10 regulate the need to represent an enterprise as a formalized architecture model that ensures transparency, controllability, consistency of views and actions of all stakeholders: from enterprise owners to software development teams. At the same time, it cannot be said that both standards are completely interchangeable, compatible or clearly complementary to each other, and the proposed architecture models provide a clear understanding of the actions necessary to realize the digital transformation of enterprises, especially mining industries.

RAMI4.0 is focused on industrial enterprises and largely develops the initial concept of Industry 4.0. In the RAMI4.0 enterprise architecture model, one of the most important aspects remains the use of the lifecycle and the products value chain integrated with the hierarchy levels of objects in the physical world (from products to the enterprise's connection to the external “connected” world) and layers of interaction (from assets to business). Of course, the use of PLM (Product Lifecycle Management) for continuous product management (from product type design to disposal of each specific instance) in order to improve the production process is a well-established practice [30]. The approach may be quite native when it comes to a machine-building enterprise, where processes can be considered as deterministic and discretized over time intervals, and where the product is a clearly delineated type and instance of a product that can be equipped with devices that transmit information about its condition in real time. However, in the case of a mining enterprise, the formalization and, most importantly, the need for continuous changes in the types and specimens of the rock mass being produced are very unobvious. Moreover, an important component of the standard is the assumption of full observability, integration, and manageability of the production environment, provided by an appropriate set of sensors, controllers, and programs, which can be described as a closed type of production environment. Mining enterprises, on the other hand, are geotechnical spatially distributed systems subject to the effects of stochastic natural phenomena, and generally have a dynamically expanding configuration of the production environment that directly changes as a result of technological processes. In this regard, the constant saturation of a mining enterprise with all kinds of devices is not completely rational, and the production environment can be characterized as partially observable, without time-stable boundaries, and attributed to systems with an open type of production environment. As a result, the direct application of the RAMI4.0 standard for the digital transformation of mining enterprises is currently difficult to implement.

The TOGAF 10 framework represents a more general approach to digital transformation, extending to processes and organizations in any field of activity, including, for example, government agencies, medical institutions or construction sites. Universality entails a large number of generalizations that require serious adaptation to the conditions of specific DT facilities. Unlike RAMI4.0, TOGAF 10 has a more rigorous instrumental methodology (since it is not a standard, but a framework), declaring a set of actions and, above all, a clear list of results that are recommended to be obtained when forming an enterprise architecture model. Such results include a set of catalogs of enterprise components, matrices of communication between components and sets of diagrams in va-rious notations (BPMN, UML, ERD, etc.), divided into four main types of architecture: business, data, applications and technologies. Despite the extensive and well-understood base of the resulting elements of the architecture model, TOGAF 10 leaves the processes of their formation, determination of accuracy, completeness, consistency, and order of implementation open and relies on the experience, knowledge, attentiveness and responsibility of participants in the digital transformation of specific enterprises. Of course, the compilation of any model is based on expert knowledge and is impossible without the participation of relevant specialists. However, in the case of large-scale industrial systems, which include mining enterprises, the lack of specific mechanisms for verifying the consistency of heterogeneous information embedded in the model entails at least high risks of disrupting the continuity of production processes. Moreover, some of the elements of the architecture model (especially diagrams in various notations) are aimed at making it easier for humans to perceive information, while digital transformation, the concept itself, and specific Industry 4.0 technologies are initially aimed at minimizing human participation in production processes. Therefore, it is impossible to speak with full confidence about the high practical applicability of the TOGAF 10 framework to obtain a model that provides any level of functional autonomy of the system.

Thus, the standards considered are largely irrelevant to the goals, objectives, and conditions of the digital transformation of mining enterprises. However, their main feature should be noted – an attempt to formalize the connection between fundamentally different components of enterprises, such as abstract concepts of business process organization (regulations, conditions, requirements, personnel roles, etc.), real-life objects of the physical world (sensors, equipment, products, resources, infrastructure elements), information (formal and informal expert knowledge; digital, analog, and neurophysiological signals measured by parameters, etc.) and software entities that implement a set of functional management tasks. In other words, in the context of building an enterprise architecture model, we are talking about the formation of knowledge about the system in order to build management mechanisms, that is, in fact, about an ontological model. Thus, the architecture model can be informally defined by some ontology, which can be transformed into a knowledge base with mechanisms for proving the consistency and truth of statements embedded in it, as well as logical inference mechanisms for making enterprise management decisions.

The creation of ontologies and knowledge bases in various subject areas occupies a significant place in the history of artificial intelligence and, as a rule, is associated with the construction of expert systems capable of helping professionals solve problematic problems. As an example for mining industries, a number of works can be cited on the construction of formal classification systems for the types and properties of coal mining equipment [31], matching the terminology of IT systems and operated mining equipment [32, 33] or managing technical inspections and repairs of equipment [34]. Despite the high degree of detail of the taxonomy, the developed ontologies are aimed at solving highly specialized problems, and the expert systems obtained on their basis are designed exclusively for interaction with personnel in enterprise management processes. The coordination of specialized ontologies among themselves or with more general ontologies of knowledge can be quite difficult or impossible, which limits their scientific and practical significance.

At the same time, the concepts of “ontology” and “knowledge base” can be used both to formalize and verify knowledge when building an enterprise architecture model, and as tools for saturating (teaching) the system with knowledge about itself to build an autonomously functioning cyber-physical industrial system. Today, OWL (Open World Language or Web Ontology Language) is one of the most expressive, flexible and promising tools for building ontologies, recommended for creating Web 3.0 semantic networks and based on descriptive logic – a highly expressive and decidable formal logical language [35-37]. The basis of descriptive logic and OWL are: one-place and two-place atomic axiomatic statements – “concepts” and “roles”; hierarchical structures (classes or categories) of interrelations between statements; the reducibility of classes and super classes to instances with the possibility of assigning values (data); a finite set of properties of relations between statements (transitivity, reflexivity, etc.), obeying basic algebraic logic; as well as a set of “reasoners” – developed logical inference mechanisms to prove the completeness and consistency of ontology, deduction of hidden (obviously undeclared) axioms and for the purpose of dialog interaction with the knowledge base.

In this paper, we propose an approach to building an ontological architecture model using the OWL language and specialized Protégé software (ver. 5.6.3) in the process of digital transformation of mining enterprises. A feature of the proposed approach is the representation of the most general concepts in the form of hierarchical classes, and the final typical components of the enterprise architecture in the form of instances of such classes. The purpose of the obtained ontology is not dialogical work with the knowledge base, but the formation of a consistent semantic connection of various mining, geological, geotechnical, and physic-technological concepts, which further determine a finite set of atomic functional tasks that are unchangeable in time to identify the structure of the program components of an autonomously functioning cyber-physical industrial system. It should be noted that the proposed approach is aimed at forming a standardized model with unified and invariant concepts that are not tied to a specific enterprise, but due to the advantages of the OWL language, the model can be easily expanded both in width and depth of hierarchies, and the names of individual statements can be changed without violating logic.

Due to the specificity of the field under consideration and the lack of terminological and semantic consensus in it, we will first characterize the concepts used in this study and introduce a number of formulations.

The architecture of enterprise A is understood as a set of structural components and a configuration of the relationships between them that determine the actual form of the organization and the principles of management of production processes. Such components are concepts of a fundamentally different nature, which can be written as:

where С1–technological processes and operations – an ordered set of purposeful interactions of objects of the physical world, leading to a change in the states of these objects; С2 – physical objects – objects of the technological environment interacting with each other when performing production tasks, which can be classified as equipment (dump trucks, excavators, etc.), infrastructure (geospatial facilities and technological zones), products (conventional units of rock mass) and resources (fuel and energy, etc.); С3– management agents – components of an enterprise capable of perceiving, processing and transmitting information about the states of physical objects to determine the order of technological processes and operations; С4 – information – possible states of physical objects described by a set of measurable parameters and data forming such states; R – relations (mappings) – a set of possible types of relationships between components.

The architecture management task can be formulated as choosing a configuration that optimizes the integral efficiency indicator of the enterprise, which can select both the amount of profit received or the volume of useful desired (products) shipped, and a more relevant volume of profit for the mining enterprise in relation to the volume of processed ore,

where F – a certain procedure for the transformation of architecture and the choice of its configuration, which would ensure the optimum of the integral criterion of enterprise efficiency ПΣ.

To solve such a macro-optimization problem, a strict formal statement is necessary, which in turn requires taking into account a greater depth of detail of the factors, identifying their relationship, and clearly defined criteria and search conditions. An attempt to reduce this problem to a single mathematical function, i.e., to fully formalize it, seems extremely difficult (and probably with unsolvable computational complexity), and therefore it is necessary to find other ways to represent it – model abstraction. It is possible to formulate a hypothesis that there is a model Ω, that allows us to describe A, determine the type F, and reduce the architecture management problem to the optimization problem of the criterion ПΣ. In this regard, for the sake of clarity, we will introduce a number of definitions and assumptions:

- At any given time, the enterprise retains its main activity, which means that the list of technological processes and operations С1, as well as the list of physical objects С2 must be comparable and equivalent.

- At any given time, the architecture of an enterprise should ensure the implementation of a complete list of technological processes and operations that explain and regulate the activities of such an enterprise.

- Digital transformation is a continuous process of non-deterministic changes in the architecture of an enterprise aimed at improving integrated efficiency.

- The integrated efficiency of an enterprise depends on the effectiveness of solving individual tasks of managing technological processes and operations.

- Management tasks are solved by management agents Ci3,j, which are staff Ci3,j=1 and software systems Ci3,j=0.

- The efficiency of solving management tasks is defined as minimizing discrepancies between the planned values of production indicators and the actual ones (AccuracyCi3,j) with minimal expenditure of time and/or resources (PerformanceCi3,j).

- Improved performance indicators for solving management problems can be achieved through the development and implementation of software components with more advanced (in terms of accuracy and performance) computing mechanisms.

Thus, digital transformation is understood as the process of replacing existing management agents with more advanced software components Ci'3,j=0. The immediate criterion for changing the architecture is the availability (and the possibility of integration into the architecture) such a software component that performs the task of management at a level of efficiency not lower than the current management agent. Then the task of architecture management during digital transformation can be written as:

It should be noted that the possibility of implementing (restrictions on changing the architecture) a new software component as a management agent should be determined by maintaining the functional integrity of the entire production system. Functional integrity should be understood as the ability of the system to solve a complete list of management tasks Φ,

where R0 – display of a set containing a complete list of management tasks Φ and a set of management agents Ci'3,j=0,

Due to the abstraction of management agents as components implementing the receipt, processing and transmission of information, regardless of their nature, the ability to solve a complete list of management tasks is considered as preserving the ability to produce a complete list and volumes of С4 information necessary for the operation of such management agents, so equation (2) can be rewritten as:

where С'4 – a set of information produced by a set of management agents Ci'3,j obtained after a change in architecture F.

In other words, when implementing a new management agent, the functional integrity of the entire system should be tested to answer the following questions:

- Can the new management agent get the information needed for the job?

- Does the new management agent produce the information necessary to maintain the working capacity of all other management agents?

- Is it possible to exclude from the architecture a management agent that previously performed this management task?

- Is it possible to introduce a new management agent without excluding the current one?

The answers to these questions can be reduced to a number of mathematical procedures, and in combination with the proposed formalization, the architecture management tasks are relevant outside the framework of discussing the digital transformation of enterprises, i.e. they are applicable not only to software systems, but also to personnel. However, in the context of this study, digital transformation is understood as the minimization or complete exclusion of human participation in the implementation of production processes, the construction of an autonomously functioning cyber-physical industrial system. This means that a multitude of physical objects С2 must perform a multitude of technological processes and operations С1 under the management of software agents С3, operating with digital information С4. In this case, the concept of enterprise architecture can be identified with the concept of software architecture, without being completely equivalent. Thus, technological processes and operations, as well as physical objects, although they can be represented by digital information objects or models in cybernetic space, nevertheless cannot become completely software entities and be excluded from the enterprise architecture. Accordingly, there is some substantial part of the architecture that is invariant for any arbitrary period of time, regardless of its changes caused by digital transformation, while part of the architecture, mainly related to management agents, can and should be modified. Based on the proposed definitions and assumptions 1 and 2, it can be concluded that as a part of the architecture model that remains unchanged over time, there should be a list of management tasks that, on the one hand, should be derived from the interconnection of the components of the architecture itself, and on the other, should be associated with specific management agents. Then the most important aspects of the digital transformation of architecture is to determine the full list of tasks implemented by management agents in order to identify their structural and functional relationship, the possibility and need for change; and procedures for manipulating management agents in terms of changing the structural configuration of the architecture.

The procedures for manipulating software components in automatic mode have been well studied and are implemented using a combination of understandable standard Git-CI/CD-Docker/Kubernetes technologies and analogues, as a result of which consideration of their implementation issues is beyond the scope of this study. However, it should be noted that the definition of the list of software components for filling Git repositories and their placement via Kubernetes on end nodes is carried out by developers and system architects. The de facto configuration of the architecture and the procedure for manipulating its structure are determined on the basis of an expert assessment of a person or group of persons operating with a certain model representation of the enterprise architecture. At the same time, the effectiveness of such procedures (non-violation of the functional integrity of the system) largely depends on the degree of elaboration of the model, its availability in general, and the ability to compare the initial architecture “as is” with what should be “to be”.

Accordingly, the first step to begin digital transformation is to identify a list of tasks for mana-gement agents that does not depend on specific management agents and meets the requirement of full functional coverage of the system. The compilation of such a list is complicated by a number of problems:

- the degree of detail depth (tasks should be sufficiently “atomized”, but not excessively decomposed to elementary operations);

- the degree of completeness (tasks should describe the entire production activity of the enterprise, including the one that is currently not a software function (implemented in the form of “mental” labor of personnel), but serves as an integral operation of the chain of technological processes);

- the degree of accuracy (the task should explain the interrelation of different types of architecture components and be equivalent to a formal computational procedure);

- the degree of consistency (the task must be unambiguous in its description and content, and also not be equivalent to another task).

It is possible to solve and obtain any quantitative estimates of the formulated problems using a model that would provide a representation of heterogeneous architectural components in the form of abstract concepts, connect them with formal logical rules and provide a computing device that guarantees the possibility of working with statements. Thus, it is proposed to consider ontological modeling as the type and mechanisms of building an architecture model.

Let А0 be the initial type of enterprise architecture at the initial stage of DT, which can be described by the “as is” model – Ω0; А′, …, А′′…′ are the types of enterprise architecture at individual stages of change, which can be described by the models Ω′, …, Ω′′…′ ; and А* is a type of enterprise architecture upon completion of digital transformation, which can be described by the “to be” model – Ω*. At any arbitrary moment of time α the enterprise possesses some architecture Аα, the type of which can (and should) be determined through the representation of the model Ωα. The continuous process of digital transformation of an enterprise →DT can be represented as a set of discrete steps, non-deterministic in time, to change the Аα, carried out until its appearance becomes equivalent to А*, which can be determined by comparing the Ωα and Ω* models.

At the initial step α = 0 the view of architecture Аα=0 should be determined, the model Ωα=0 should be compiled, the final type of architecture А* should be determined, and the corresponding immutable model Ω* should be compiled. Next, starting from step α = 1 to α = *, it is necessary to evaluate the compliance of the current architecture model Ωα with the required Ω*, determine the need and possibility of modifying the architecture, and make decisions on making changes. Then the process of enterprise architecture management in the context of digital transformation DT can be written as:

where →DT – a set of discrete steps to change the architecture (1) to bring the enterprise to the form of an autonomously functioning industrial system.

At the same time, the following conditions must be true at each stage:

where Frule of inference – a mechanism for the logical derivation of a complete list of atomic tasks of management agents Φ from the ontological architecture model Ωα. Then each atomic task φ ∈ Φ can be assigned a management agent Ci3,j that implements it as part of the architecture.

Also, achieving the fulfillment of (3), i.e. deducibility of the complete list of atomic tasks Ф from the Ωα ontology, is possible only when the Ωα ontology is consistent,

Consistency of ontology should be understood as the truth of all axiomatic statements embedded in it in the form of declared concepts and relations between them.

Therefore, it is necessary to compile a set of conceptual expressions that will form the basis of the ontological model of the mining enterprise architecture, link them with an appropriate set of relations that determine the company's activities, and check the obtained ontology for consistency in order to confirm the hypotheses outlined and the possibility of further work in the field of digital transformation.

Results and discussions

Due to the limitations of the presentation of all the theoretical concepts embedded in the proposed ontology of mining enterprise architecture, here are some key examples:

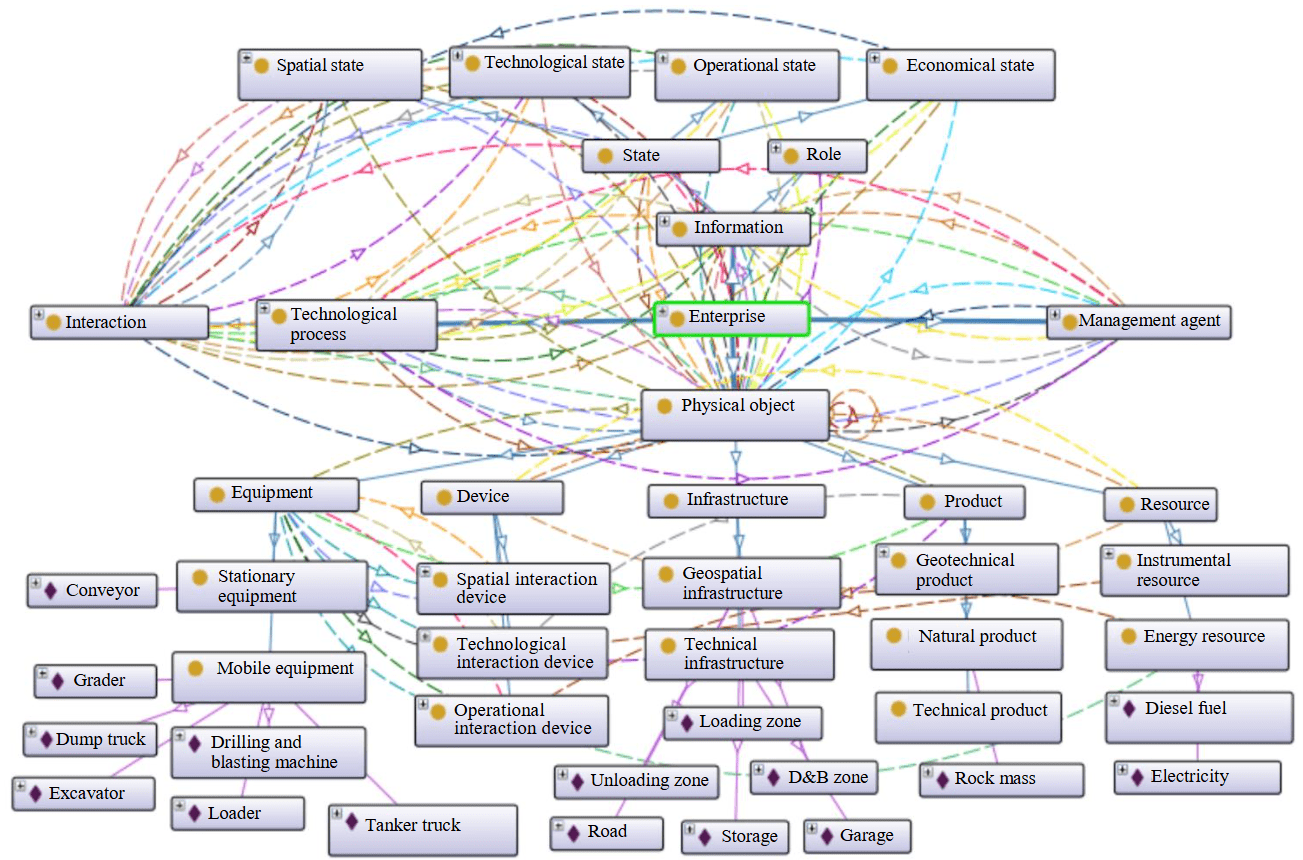

- an enterprise consists of technological processes, physical objects, management agents and information related to each other, having their own taxonomy (hierarchical classification) with end instances in the form of standard (uncountable and not having their own unique names) components;

- the physical objects are understood as elements of the production environment that do not have independent decision-making, including: equipment (outlined specimens – dump truck, conveyor, excavator, etc.), infrastructure (geospatial – road, board, dump; technical – loading area, warehouse, maintenance garage), devices (components of equipment – bucket, chassis, etc.), product (natural – rock mass block; geotechnical – roadbed; etc.), resource (energy – fuel, electricity; instrumental – water, explosive);

- each physical object has states, which are understood as abstract spatial, technological, operational and economic information properties described by a group of data in the form of measurable physical or economic quantities;

- the atomic task of the management agent φ(Ci'3,j) ∈ Φ is understood as a class of computational procedure for determining changes in the state of a physical object during its pairwise interactions with other physical objects acceptable within the framework of a technological process at a certain point in time;

- as a class of computational procedure, the classical tasks of the theory of automated control systems are assumed: detection, identification, predicting, planning, and control.

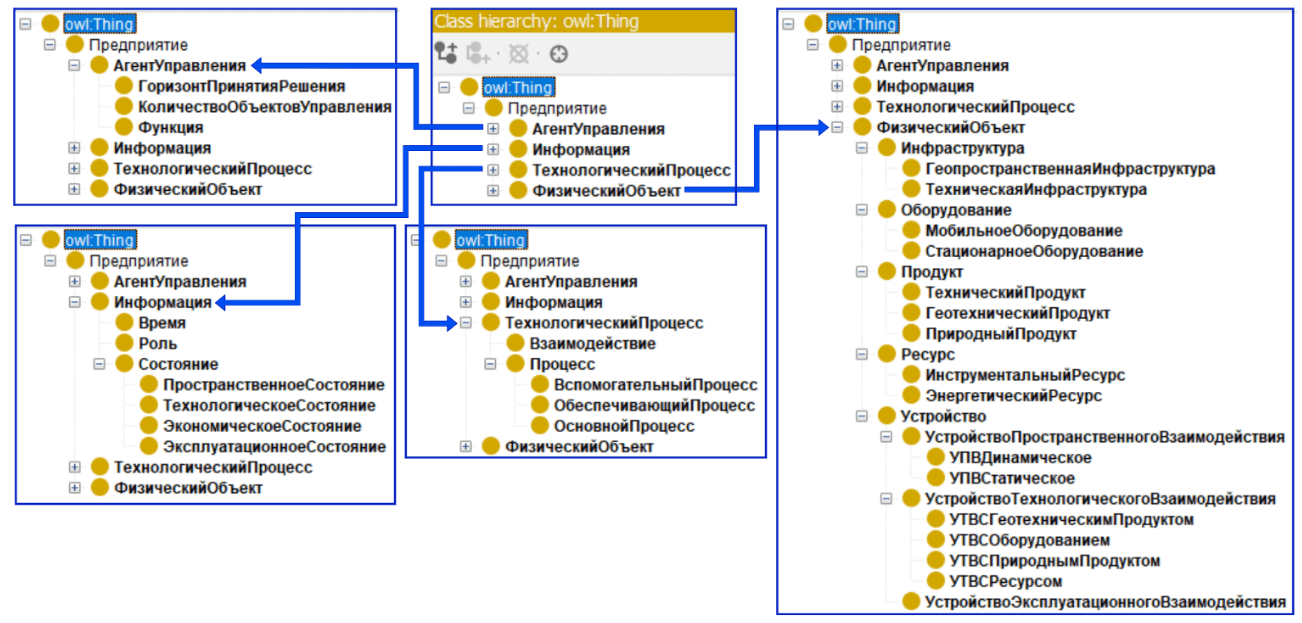

The full set of common classes and the hierarchical structure of the resulting model is shown in Fig.1. The implementation of the ontology was carried out in the OWL language in the Protégé software environment ver. 5.6.3.

The proposed taxonomy is formed based on general interdisciplinary concepts, intentionally created in the form of a general-purpose ontology in order to enable potential alignment with other more general ontologies (time, physical quantities, etc.) or, conversely, special-purpose ones (including such as [32-35]). One of the important characteristic features of the taxonomy is its applicability to geospatial industrial systems in which natural and technical components act as the core of activity, starting from the production environment itself (spatial infrastructure facilities) to the products.

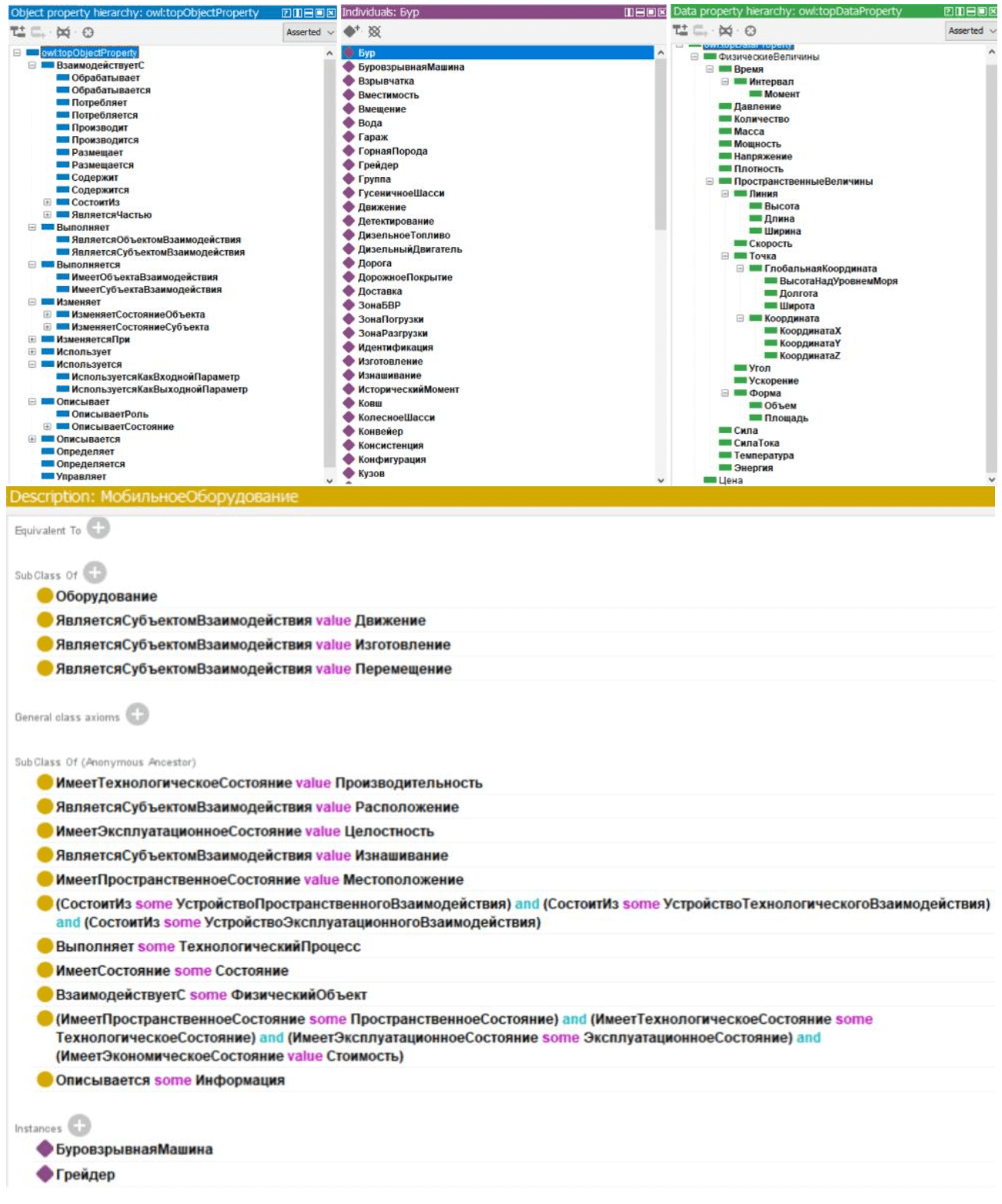

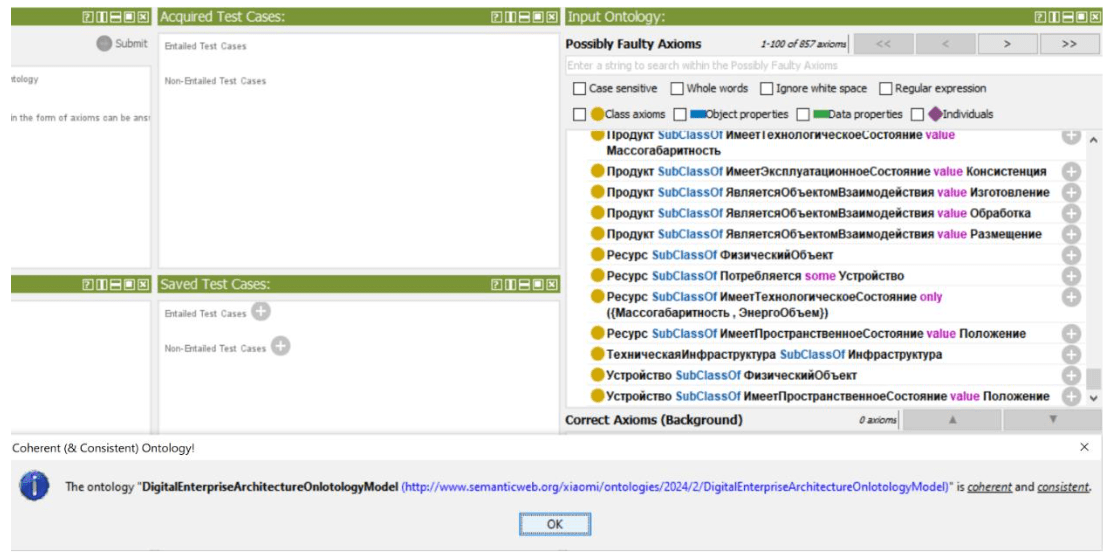

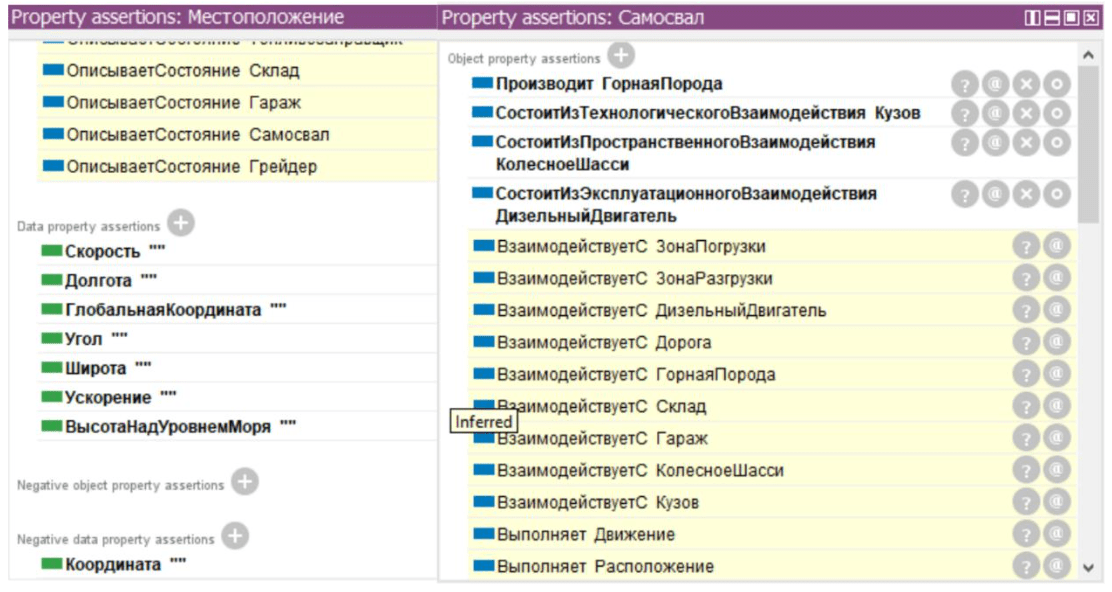

Including of individual instances in the form of well-understood and stable entities for each of the final taxonomy classes is a mandatory addition and a possible application of this ontology in the context of mining enterprises (currently mainly open-pit mining enterprises). Together with a set of properties-relationships between concepts explaining the roles of each instance and a set of data in the form of various measurable quantities (Fig.2) defining the concepts of “states” of physical objects, the resulting special-purpose ontology forms the basic architecture model of a mining enterprise. The lower part of Fig.2 shows an example of assigning sets of a priori axiomatic relations to classes of a hierarchy with other classes and instances that determine the logical and semantic construction of the model. Note that the individual names in the current version of the ontology are illustrative in order to explain the proposed approach aimed at standardizing the way the architecture model is formed. Clear formulation of specific names should be carried out by joint efforts of expert groups from among scientific and industry specialists during open discussions.

Fig.1. Hierarchy of classes of concepts of the ontological model of enterprise architecture

Fig.2. Fragments of the hierarchy table of relations between concept classes (Object property hierarchy, blue) and their instances; instance tables (Individuals, purple) and data hierarchy tables (Data property hierarchy, green); an example of the formation of initial (a priori) logical axioms for the concept class “Mobile Equipment” (Description, yellow)

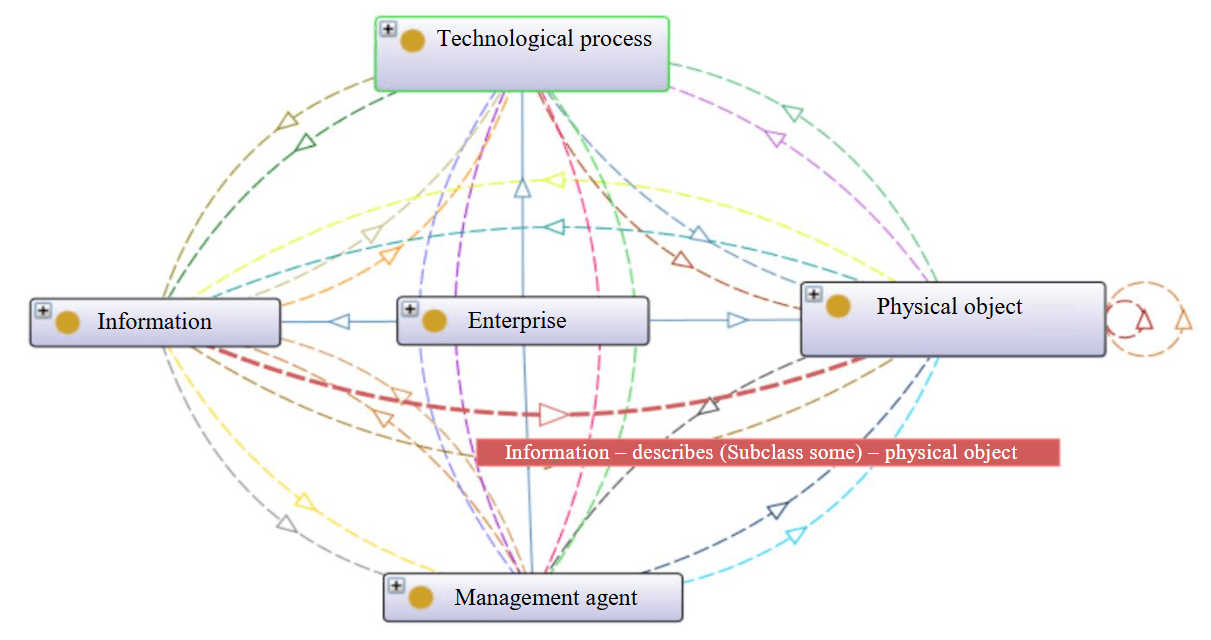

As a result of declaring all the axioms, the resulting ontological model can be represented as a semantic graph, where classes and their instances act as nodes, and the relationships between them act as edges (Fig.3, 4).

Due to the high dimension of the resulting semantic graph, it is rather difficult to represent its full form in the framework of this work. For example, Fig.4 shows a fragment of the semantic graph detail when the “Physical object” branch is expanded to its final instances.

Fig.3. Fragment of the semantic graph of ontology

Fig.4. A fragment of the detail of the semantic graph of the ontology

To determine the achievement of the key goal of this study, which is to confirm the consistency of the obtained ontology, one of the most traditional and developed methods of descriptive logic, HermiT ver. 1.4.3.456, was used [36]. Reasoner presents a logical inference mechanism to prove the completeness and consistency of the underlying axioms and to deduce hidden a posteriori relationships in the semantic graph.

Figure 5 shows a visualization of HermiT's work through the tools for testing and debugging ontologies. In the lower part of the screen, a message in a pop-up window indicates the confirmation of coherence (interconnectedness of all axioms) and consistency of the resulting ontology.

Figure 6 shows examples of visualization of the reasoner's work for deducing a posteriori relationships of class instances that were not declared “manually” at the stage of ontology formation.

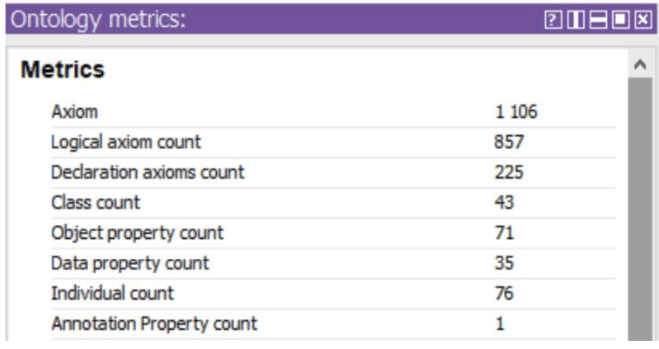

Figure 7 shows metric estimates of the number of axiomatic statements (including a priori declared and logically derived ones) for the current version of the ontology.

Fig.5. Confirmation of coherence and consistency of ontology by built-in axiom proof tools

Fig.6. Visualization of the HermiT risoner's work results for the “Location” and “Dump truck” instances

Fig.7. Metrics of ontology in terms of the number of axioms, classes, relationships, and instances

Thus, the achievability of the set research goal has been determined and the initial hypotheses about the possibility of building an enterprise architecture model based on onto-logy in order to ensure the digital transformation of mining industries have been confirmed. At the moment, a sufficient number of class instances have not been introduced into the ontology, which are the basic components of the architecture of mining enterprises. This is explained by the fact that the proposed ontology is aimed at unifying and standardizing the architecture model of mining industries, and therefore, the participation of a wide range of industry experts is necessary to ensure exhaustive depth, completeness, and uniformity of the taxonomy. The current model is proposed to be considered as a basic illustrative example of the formation of a comprehensive digital transformation methodology for building autonomously functioning geospatial industrial systems. In the future, based on the obtained model, it is planned to form a logical inference mechanism (3), (4), as well as a formal definition of the procedure for managing the structural configuration of the architecture in terms of management agents (1).

Conclusion

A number of conceptual statements of tasks and criteria for managing the digital transformation of mining enterprises are proposed, declaring the minimization or complete exclusion of human participation in the implementation of technological processes and, as a result, the construction of an autonomously functioning cyber-physical industrial system. The necessity of forming a knowledge model about the structural and functional properties of such a system in order to ensure self-organization and self-regulation is shown, and the requirements for the instrumental means of implementing the model are formulated.

It is determined that an enterprise architecture model should be understood as a knowledge model, regulating a set of key components with a complexly formalized heterogeneous essence and their interrelation. The impossibility of using existing standards and frameworks (RAMI 4.0, TOGAF 10) to build an enterprise architecture model to ensure the DT processes of geospatial natural and technical industrial systems with an open type of production environment is substantiated.

A number of principles and mechanisms for forming an architecture model of an independently functioning cyber-physical industrial system based on ontological modeling are formulated. The mechanism of application of the model in the management structure of the digital transformation of the enterprise is explained. In accordance with the proposed approach, the basic architecture model of a mining enterprise was formed in the form of general and special purpose ontologies in the OWL descriptive logic language in the Protégé environment. The resulting ontological model has undergone a formal coherence and consistency verification procedure, which suggests partial confirmation of the initial hypotheses and the possibility of further research into the formalization of methodolo-gical aspects of the digital transformation of mining industries.

Access to data

The resulting model is applied for the possibility of independent verification, as well as for the open participation of those interested in its development:

References

- Alkhalaf T., Durrah O., Alkhalaf M. Digital Transformation, Business Model, and Performance in the Context of Digital SMEs: Evidence From France // Digital Technologies for Sustainability and Quality Control. IGI Global Scientific Publishing, 2025. P. 101-120. DOI: 10.4018/979-8-3693-4373-9.ch005

- Makarenko Ya.V., Solovyeva I.А. Digital transformation of the enterprise: key definitions, principles and approaches. Bulletin of the South Ural State University. Series “Economics and Management”. 2025. Vol. 19. N 1, p. 112-123 (in Russian). DOI: 10.14529/em250109

- Litvinenko V.S. Digital Economy as a Factor in the Technological Development of the Mineral Sector. Natural Resources Research. 2019. Vol. 29. Iss. 3, p. 1521-1541. DOI: 10.1007/s11053-019-09568-4

- Yong Fang, Xiaoyan Peng. Micro-Factors-Aware Scheduling of Multiple Autonomous Trucks in Open-Pit Mining via Enhanced Metaheuristics. Electronics. 2023. Vol. 12. Iss. 18. N 3793. DOI: 10.3390/electronics12183793

- Sobolev А.А. Review of case history of unmanned dump trucks. Gornyi zhurnal. 2020. N 4, p. 51-55 (in Russian). DOI: 10.17580/gzh.2020.04.10

- Temkin I.O., Deryabin S.A., Al-Saeedi A.A.К., Konov I.S. Operational planning of road traffic for autonomous heavy-duty dump trucks in open pit mines. Eurasian Mining. 2024. N 2, p. 89-92. DOI: 10.17580/em.2024.02.19

- Vladimirov D.Ya., Klebanov A.F., Kuznetsov I.V. Digital Transformation of Surface Mining and New Generation of Open-Pit Equipment. Mining Industry Journal. 2020. N 6, p. 10-12 (in Russian). DOI: 10.30686/1609-9192-2020-6-10-12

- Lukichev S.V., Nagovitsin O.V. Digital transformation of mining industry: Past, Present and Future. Gornyi zhurnal. 2020. N 9, p. 13-18 (in Russian). DOI: 10.17580/gzh.2020.09.01

- Klebanov A.F., Bondarenko A.V., Zhukovsky Yu.L., Klebanov D.A. Establishing remote control centers of a mining operation: strategic prerequisites and implementation stages. Russian Mining Industry. 2024. N 4, p. 174-183 (in Russian). DOI: 10.30686/1609-9192-2024-4-174-183

- Klebanov A.F., Sizemov D.N., Kadochnikov M.V. Integrated Approach to Remote Monitoring of Technical and Operating Conditions of Mine Dump Trucks. Russian Mining Industry. 2020. N 2, p. 75-81 (in Russian). DOI: 10.30686/1609-9192-2020-2-75-81

- Koteleva N., Valnev V. Automatic Detection of Maintenance Scenarios for Equipment and Control Systems in Industry. Applied Sciences. 2023. Vol. 13. Iss. 24. N 12997. DOI: 10.3390/app132412997

- Zhukovskiy Y.L., Kovalchuk M.S., Batueva D.E., Senchilo N.D. Development of an Algorithm for Regulating the Load Schedule of Educational Institutions Based on the Forecast of Electric Consumption within the Framework of Application of the Demand Response. Sustainability. 2021. Vol. 13. Iss. 24. N 13801. DOI: 10.3390/su132413801

- Korolev N.A., Zhukovskiy Y.L., Buldysko A.D. et al. Energy resource evaluation from technical diagnostics of electromechanical devices in minerals sector. Mining Informational and Analytical Bulletin. 2024. N 5, p. 158-181 (in Russian). DOI: 10.25018/0236_1493_2024_5_0_158

- Zhukovskiy Y., Koshenkova A., Vorobeva V. et al. Assessment of the Impact of Technological Development and Scenario Forecasting of the Sustainable Development of the Fuel and Energy Complex. Energies. 2023. Vol. 16. Iss. 7. N 3185. DOI: 10.3390/en16073185

- Zakharov V.N., Kaplunov D.R., Klebanov D.A., Radchenko D.N. Methodical approaches to standardization of data acquisition, storage and analysis in management of geotechnical systems. Gornyi zhurnal. 2022. № 12, p. 55-61 (in Russian). DOI: 10.17580/gzh.2022.12.10

- Sahal R., Breslin J.G., Ali M.I. Big data and stream processing platforms for Industry 4.0 requirements mapping for a predictive maintenance use case. Journal of Manufacturing Systems. 2020. Vol. 54. P. 138-151. DOI: 10.1016/j.jmsy.2019.11.004

- López Martínez P., Dintén R., Drake J.M., Zorrilla M. A big data-centric architecture metamodel for Industry 4.0. Future Generation Computer Systems. 2021. Vol. 125, p. 263-284. DOI: 10.1016/j.future.2021.06.020

- Deryabin S.A., Rzazade Ulvi Azar ogly, Kondratev E.I., Temkin I.O. Metamodel of autonomous control architecture for transport process flows in open pit mines. Mining Informational and Analytical Bulletin. 2022. N 3, p. 117-129 (in Russian). DOI: 10.25018/0236_1493_2022_3_0_117

- Schmitt R., Borck C., Behm M., Böhnke J. Approach of an asset combination based on RAMI4.0 for the digital transformation and operation of a Digital Twin. Procedia CIRP. 2024. Vol. 130, p. 724-729. DOI: 10.1016/j.procir.2024.10.155

- Deryabin S.A., Temkin I.O., Zykov S.V. About some issues of developing Digital Twins for the intelligent process control in quarries. Procedia Computer Science. 2020. Vol. 176, p. 3210-3216. DOI: 10.1016/j.procs.2020.09.128

- Sakurada L., Leitao P., De La Prieta F. Agent-Based Asset Administration Shell Approach for Digitizing Industrial Assets. IFAC-PapersOnLine. 2022. Vol. 55. Iss. 2, p. 193-198. DOI: 10.1016/j.ifacol.2022.04.192

- Reinpold L.M., Wagner L.P., Gehlhoff F. et al. Systematic comparison of software agents and Digital Twins: differences, similarities, and synergies in industrial production. Journal of Intelligent Manufacturing. 2025. Vol. 36. Iss. 2, p. 765-800. DOI: 10.1007/s10845-023-02278-y

- Angreani L.S., Vijaya A., Wicaksono H. Enhancing strategy for Industry 4.0 implementation through maturity models and standard reference architectures alignment. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management. 2024. Vol. 35. Iss. 4. p. 848-873. DOI: 10.1108/JMTM-07-2022-0269

- Leitão P., Karnouskos S., Strasser T.I. et al. Alignment of the IEEE Industrial Agents Recommended Practice Standard With the Reference Architectures RAMI4.0, IIRA, and SGAM. IEEE Open Journal of the Industrial Electronics Society. 2023. Vol. 4, p. 98-111. DOI: 10.1109/OJIES.2023.3262549

- Villar E., Martín Toral I., Calvo I. et al. Architectures for Industrial AIoT Applications. Sensors. 2024. Vol. 24. Iss. 15. N 4929. DOI: 10.3390/s24154929

- Shirbazo A., Binghao Li, Ata S. et al. A Guideline for the Standardization of Smart Manufacturing and the Role of RAMI 4.0 in Digitising the Industrial Sector. IEEE Internet of Things Journal. 2025. Vol. 12. Iss. 12, p. 19090-19118. DOI: 10.1109/JIOT.2025.3559929

- Esposito G., Romagnoli G. A Reference Model for SMEs understanding of Industry 4.0. IFAC-PapersOnLine. 2021. Vol. 54. Iss. 1, p. 510-515. DOI: 10.1016/j.ifacol.2021.08.166

- Safitri S.R., Mulyana R., Fajrillah A.A.N. Developing enterprise architecture for BPRACo SMEs digital transformation by using TOGAF 10. Jurnal Informatika dan Komputer. 2024. Vol. 7. N 3, p. 165-174. DOI: 10.33387/jiko.v7i3.8629

- Afarah S.F., Hindarto D., Wahyuddin M.I. Optimizing Automotive Manufacturing Systems through TOGAF Modelling. SinkrOn. 2024. Vol. 8. N 1, p. 414-425. DOI: 10.33395/sinkron.v9i1.13256

- Khai Min Chew, Lee Wah Pheng. Product Life Cycle Data Management and Analytics in RAMI4.0 using the Manufacturing Chain Management Platform. Journal of the Institution of Engineers. 2021. Vol. 82. N 3, p. 101-108. DOI: 10.54552/v82i3.120

- Baolong Zhang, Xiangqian Wang, Huizong Li, Miaomiao Jiang. Knowledge modeling of coal mining equipments based on ontology. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 2017. Vol. 69. N 012136. DOI: 10.1088/1755-1315/69/1/012136

- Stanković R.M., Obradović I., Kitanović O., Kolonja L. Towards a Mining Equipment Ontology. 12th International Conference “Research and Development in Mechanical Industry”, 14-17 September 2012, Vrnjačka Banja, Serbia. SaTCIP, 2012, p. 10.

- Kolonja L., Stanković R., Obradović I. et al. Development of terminological resources for expert knowledge: a case study in mining. Knowledge Management Research & Practice. 2016. Vol. 14. Iss. 4, p. 445-456. DOI: 10.1057/kmrp.2015.10

- Vlasenko L., Lutska N., Zaiets N. et al. Core Ontology for Describing Production Equipment According to Intelligent Production. Applied System Innovation. 2022. Vol. 5. Iss. 5. N 98. DOI: 10.3390/asi5050098

- Motik B., Shearer R., Horrocks I. Hypertableau Reasoning for Description Logics. Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research. Vol. 36, p. 165-228. DOI: 10.1613/jair.2811

- Herron D., Jiménez-Ruiz E., Weyde T. On the Potential of Logic and Reasoning in Neurosymbolic Systems Using OWL-Based Knowledge Graphs. Neurosymbolic Artificial Intelligence. 2025. Vol. 1, p. 15. DOI: 10.1177/29498732251320043

- Jiaoyan Chen, Pan Hu, Jimenez-Ruiz E. et al. OWL2Vec*: embedding of OWL ontologies. Machine Learning. 2021. Vol. 110. Iss. 7. p. 1813-1845. DOI: 10.1007/s10994-021-05997-6