Diamondiferous garnet lherzolite from the V.Grib kimberlite pipe: relationship between subduction, mantle metasomatism and diamond formation

- 1 — Ph.D. Senior Researcher V.S.Sobolev Institute of Geology and Mineralogy SB RAS ▪ Orcid

- 2 — Junior Researcher V.S.Sobolev Institute of Geology and Mineralogy SB RAS ▪ Orcid

- 3 — Ph.D., Dr.Sci. Director A.N.Zavaritsky Institute of Geology and Geochemistry UB RAS ▪ Orcid

Abstract

The article presents the results of a comprehensive study of diamondiferous lherzolite from the V.Grib kimberlite pipe. The composition of rock-forming minerals (olivine, orthopyroxene, Cr-diopside, Cr-pyrope) in terms of major elements mainly corresponds to minerals from inclusions in diamonds of the lherzolite association and diamondiferous lherzolites of the world. The elevated modal amount of orthopyroxene (18 vol.%) as well as the concentration of FeO (7.5 wt.%) and the value of MgO/SiO2 ratio (0.89) for lherzolite allow assigning it to orthopyroxene-enriched lherzolites. Specific features of the composition of Cr-diopside and Cr-pyrope in respect of rare elements indicate that at the time of capture by kimberlite, lherzolite retained the signs of a slight impact of mantle metasomatism. Modelling results allowed suggesting magnesiocarbonate and silicate high-density fluids (HDF) as the metasomatic agent. No signs of influence of proto-kimberlite melt were found. The degree of nitrogen aggregation in diamond (%B from 6 to 15) indicates a long stay in mantle conditions, which excludes formation shortly before the emplacement of kimberlite. Extremely light values of carbon isotope composition (δ13C = –18.59 ‰) indicate the involvement of organic carbon of subduction origin in diamond formation. Diamond formation could be associated with an ancient metasomatic event occurring with the leading role of low-Mg silicate-carbonate HDF, the source of which were eclogites and/or subducted sedimentary deposits containing organic carbon. The calculated P-T parameters (3.7 GPa, 814 °C) of the last equilibrium of mineral phases of lherzolite point to its capture from a depth of ~118 km, which corresponds to a section of the lithospheric mantle (approximately 95-120 km), within which rocks also demonstrating features of specific transformations under the influence of subduction-related fluids were earlier discovered.

Funding

The analytical work was carried out at the expense of the RSF grant 20-77-10018. Xenolith sample was collected as part of field work under the State assignment of IGM SB RAS N 122041400241-5.

Introduction

Identification and characteristics of rocks that are the substrate for diamond formation in the lithospheric mantle are possible due to the study of their syngenetic or synchronous mineral inclusions [1-3] as well as diamondiferous mantle rocks proper (peridotites and eclogites) which occur as xenoliths in kimberlites [4-6] and lamproites [7]. The analysis of mineral inclusions in diamonds allows identifying the features of diamond-forming environment [1] and estimating the time of diamond formation [3], and the study of diamondiferous mantle xenoliths additionally makes it possible to reconstruct the stages of lithospheric mantle evolution to the time of kimberlite or lamproite magmatism and to establish the relationship between episodes of diamond formation and tectono-thermal events in the lithospheric mantle and the lower crust [3, 5].

The results of the study of mineral inclusions in diamonds from kimberlite pipes of the M.V.Lomonosov and V.Grib deposits in the Arkhangelsk Diamond Province (ADP) [8, 9] lying in the northern East European Platform suggest that peridotites are the dominant substrate for diamonds with a subordinate role of eclogites [10-12], which is typical for most diamonds in the world [1]. Despite numerous comprehensive studies of diamonds from the ADP deposits [13-15], data on the concentrations of major elements in pyropes and Cr-diopsides included in ADP diamonds of the peridotite association are limited [8, 9], and data on the contents of rare elements were not yet obtained [16]. This does not allow to reliably establish the relationship between the stages of diamond formation and certain metasomatic events in the lithospheric mantle of the ADP [16, 17], to assess the thermal regime of the lithospheric mantle at the stages of diamond formation and to determine the range of diamond distribution depths [18, 19].

The paper presents the results of a comprehensive study of diamondiferous lherzolite from the V.Grib kimberlite pipe, including data on the concentrations of major elements in rock-forming minerals, rare elements in Cr-pyrope and Cr-diopside, reconstructed bulk chemical composition of lherzolite and the results of calculating the P-T parameters of the last equilibrium of mineral associations as well as data on the defect-impurity and isotope compositions of carbon in diamond extracted from lherzolite. The information obtained is used to reconstruct the stages of lherzolite formation and transformation as well as to determine the genesis of diamond.

Methods

Lherzolite G1-3 was found in a kimberlite sample from the diatreme part of the V.Grib pipe (sampling depth 380 m from the surface) as a rounded xenolith measuring 4×3×1.5 cm. The central part of the xenolith measuring 2×1.5×1 cm was carefully extracted to exclude contamination with kimberlite and manually crushed to fractions from +2 to –0.1 mm. A diamond crystal was found in the mineral fraction of –1 + 0.5 mm. From the same mineral fraction, 10 visually “fresh” grains of pyrope and Cr-diopside without mineral inclusions and secondary alterations were selected. These grains were mounted in epoxy, polished and coated with carbon. All analytical work, with the exception of determining the concentrations of rare elements in pyrope and Cr-diopside, was carried out at the Analytical Center for Multi-Element and Isotope Studies at IGM SB RAS (Novosibirsk).

Mineralogical and petrographic study of lherzolite was performed in a flat-polished thin section using a ZEISS Аxiolab 5 optical microscope equipped with an Axiocam 208 colour high-resolution digital camera and a Tescan MIRA 3 LMU scanning electron microscope equipped with an INCA Energy 450 X-Max 80 microanalysis system (Oxford Instruments Ltd.). Concentrations of major elements in rock-forming minerals were determined on a JEOL JXA-8100 electron probe microanalyzer at an accelerating voltage 20 kV, beam current 50 nA, and beam size 1 μm. Natural mineral standards of IGM SB RAS were used for calibration. Relative standard deviations were within 1.5 %. The results were obtained for 10 s at the peak as well as for 10 s on both sides of the background; ZAF correction was applied. The detection limits were < 0.05 wt.% for all analysed elements, including 0.01 wt.% for Cr and Mn; 0.02 wt.% for Ti and Na; 0.05 wt.% for K.

Trace element concentrations in pyrope and Cr-diopside were determined in a flat-polished thin section mounted in epoxy, polished and coated with carbon using an XSERIES2 quadrupole inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) combined with a 213 nm wavelength laser sampling device (Nd:YAG solid-state laser, New Wave Research) at the Analytical Centre of Novosibirsk State University. Before each determination, the analysed area of the mineral was checked in transmitted and reflected light for the absence of cracks, microinclusions and secondary alterations. The analysis was conducted at frequency 20 Hz with pulse energy 12 mJ/cm–2 and beam size 50 μm. Helium was used as a carrier gas. Data collection time was 90 s per point including 30 s for the background and 60 s for the signal. NIST 612 and NIST 614 reference samples were used as external standards. The drift of the instrument sensitivity was controlled by surveying NIST 610 as an unknown sample. Two analyses of NIST 612 standard were performed before and after every ten measurements. The detection limits were: 0.001 ppm for La, Pr, Nb, Tb, Ho, Y, Tm, Lu; 0.002 ppm for Ce, Ta, Th; 0.003 ppm for Eu, Sr; 0.005 ppm for Zr, Nd, Dy, Er, Hf, U; 0.01 ppm for Sm, Yb; 0.02 ppm for V, Ba, Gd; 0.1 ppm for Sc, Mn, Co; 0.6 ppm for Cr, Ni; 1 ppm for Ti. Ca concentrations determined by electron probe analysis were used as internal standards.

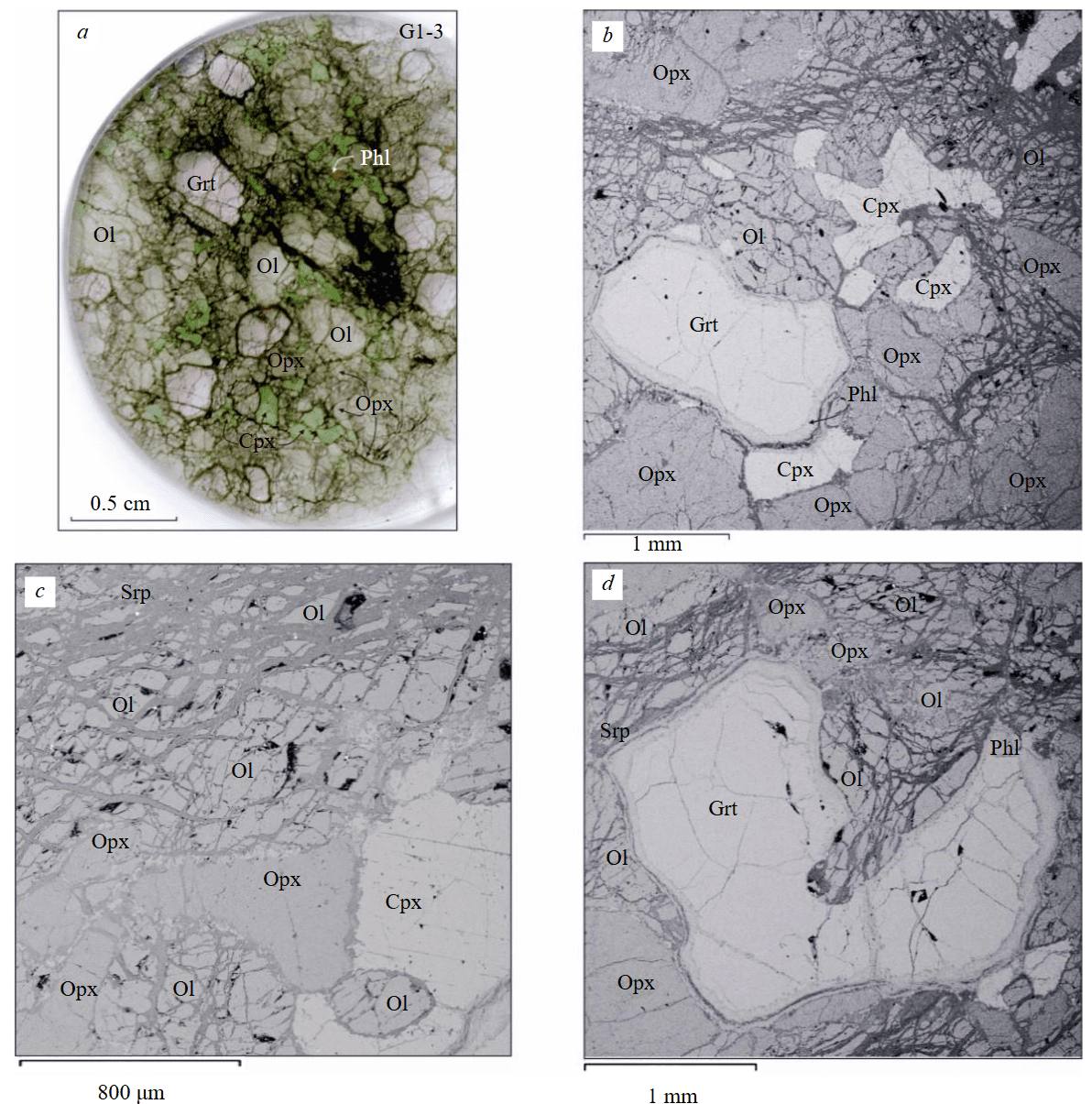

Fig.1. Mineralogical and petrographic features of diamondiferous lherzolite G1-3 from the V.Grib kimberlite pipe: a – general view of a flat-polished thin section; b-d – images in backscattered electrons

Ol – olivine; Opx – orthopyroxene; Cpx – clinopyroxene; Grt – garnet; Phl – phlogopite; Srp – serpentine

The defect-impurity composition of diamond was studied using infrared (IR) spectroscopy on a Bruker Vertex 70 spectrometer combined with a HYPERION 2000 IR microscope. Absorption spectra were recorded in the central and edge zones of crystal in the wave interval 600-4500 cm–1 with an aperture 50×50 μm and spectral resolution 1 cm–1. Spectra processing and normalization to the internal absorption of diamond were carried out in the OPUS (version 5.0, BRUKER OPTIK, USA) and SpectrExamination (developed by O.E.Kovalchuk, PJSC ALROSA) software. Nitrogen concentrations in the form of A- and B1-defects were calculated using the coefficients from article [20].

Identification of an inclusion in diamond was performed using a Horiba Jobin Yvon LabRAM HR800 Raman spectrometer equipped with a 532 nm Nd:YAG laser and an Olympus BX41 microscope. Spectra were recorded in the wavelength band 200-1200 cm–1 at exposure time 7 s and magnification 50x.

Carbon isotope composition (δ13C) of diamond was obtained on a Delta V Advantage mass spectrometer. Measurement was accomplished in dual gas injection mode. The ground sample was subjected to full volume oxidation to CO2 in a vacuum reactor. For quality control of measurements, graphite standards USGS-24 (δ13C = –16.049 ‰) and GR-770 (δ13C = –24.65 ‰) were used.

Results

Xenolith G1-3 is a garnet (11 vol.%) containing lherzolite consisting of predominant olivine (61 vol.%) as well as ortho- (18 vol.%) and clinopyroxene (10 vol.%). Lherzolite is characterized by a coarse-grained texture, grain sizes of rock-forming minerals reach 5 mm (Fig.1). The sample contains phlogopite (< 1 vol.%) which occurs both as individual large (to 2 mm) tabular grains (Fig.1, a), and as rims around garnet grains (Fig.1, b, d). Olivine grains are penetrated by numerous cracks along which serpentine develops (Fig.1). All rock-forming minerals of lherzolite are homogeneous in composition without signs of chemical zoning (Table 1, Fig.2, 3).

Table 1

Average concentrations of major elements in rock-forming minerals and reconstructed bulk composition of lherzolite G1-3, wt.%

|

Element |

Olivine |

Orthopyroxene |

Cr-diopside |

Cr-pyrope |

Bulk composition of rock |

|

|

SiO2 |

41.10 |

57.72 |

55.46 |

41.91 |

45.62 |

|

|

TiO2 |

ND |

0.02 |

0.05 |

0.07 |

0.02 |

|

|

Al2O3 |

ND |

0.53 |

2.39 |

21.81 |

2.73 |

|

|

Cr2O3 |

b.d.l. |

0.15 |

1.30 |

2.05 |

0.38 |

|

|

FeO |

8.70 |

5.54 |

1.77 |

9.28 |

7.50 |

|

|

MnO |

0.08 |

0.12 |

0.05 |

0.43 |

0.12 |

|

|

MgO |

49.74 |

35.77 |

15.97 |

19.63 |

40.53 |

|

|

CaO |

0.01 |

0.18 |

21.02 |

4.73 |

2.66 |

|

|

Na2O |

ND |

0.03 |

1.92 |

0.02 |

0.20 |

|

|

NiO |

0.39 |

ND |

ND |

ND |

0.24 |

|

|

Sum |

100.02 |

100.07 |

99.94 |

99.92 |

100.01 |

|

|

Mg# |

91.1 |

92.0 |

94.2 |

79.0 |

90.6 |

|

Note. ND – no data; b.d.l. – below detection limit.

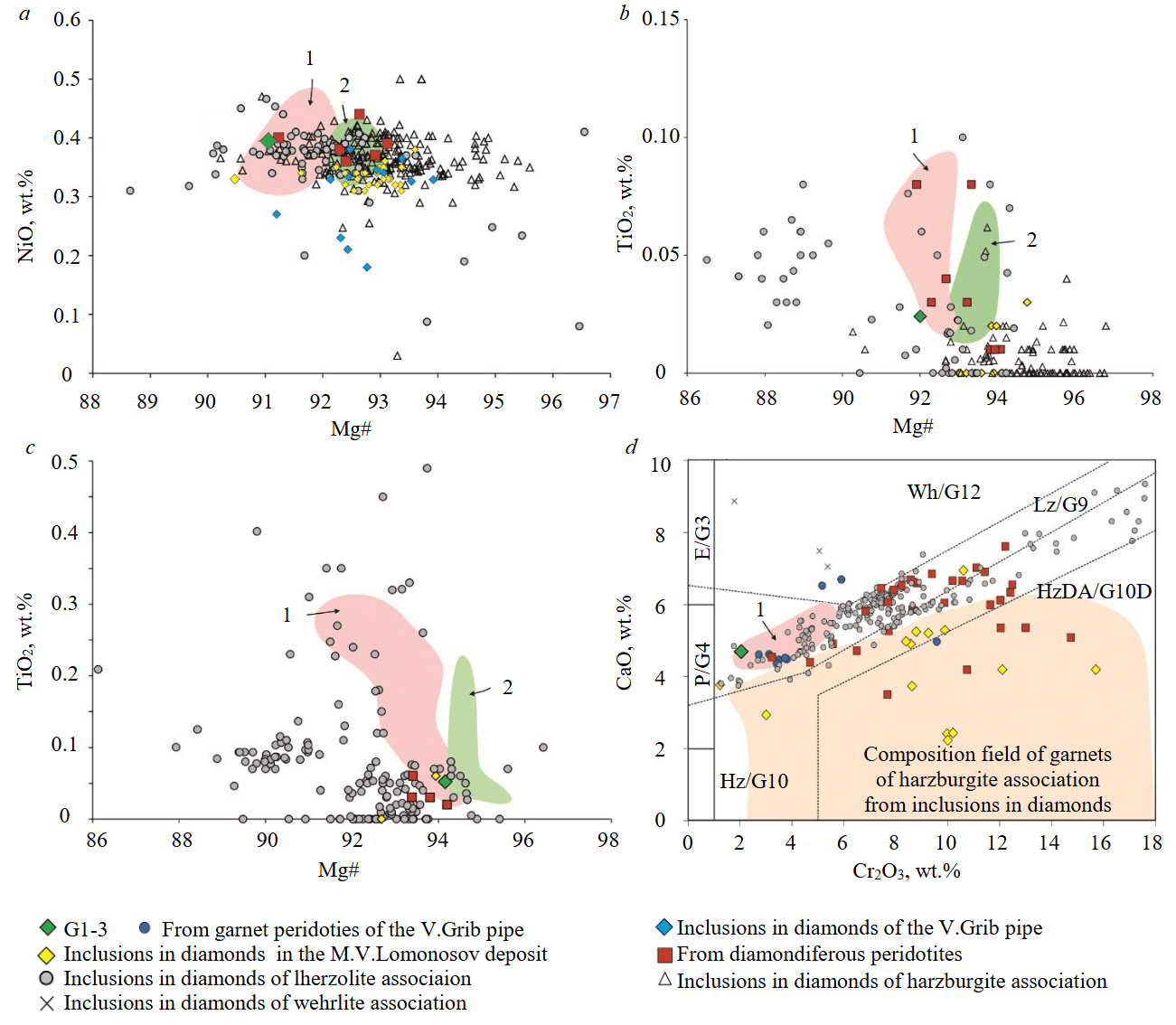

Olivine is represented by forsterite with Mg# = Mg/(Mg + Fe) × 100 = 91.1 and NiO concentration 0.4 wt.%. In composition, olivine corresponds to olivines from phlogopite-garnet lherzolites of the V.Grib pipe (see Fig.2, a). Mg# values of olivine G1-3 correspond to Mg# of olivines of cratonic garnet lherzolites of the world (Mg# av 91.5±1.2 [1]) and olivines of the lherzolite association from inclusions in diamonds of the world (Mg#av 91.8±1.0 [1]), see Fig.2, a). Mg# values of olivine G1-3 are lower than for most olivines from inclusions in diamonds from the V.Grib and M.V.Lomonosov deposit kimberlite pipes (except for three grains with Mg# 90.5-91.6; see Fig.2, a) as well as olivines of the harzburgite association from inclusions in diamonds of the world (Mg#av 93.1±0.9 [1]). Published data on the composition of olivines from diamondiferous peridotites are limited [5, 7, 21], since in most samples olivine is completely replaced by serpentine [4, 6]. Nevertheless, olivine G1-3 has an identical composition to olivine from diamondiferous lherzolite of the Argyle lamproite pipe [7] (see Fig.2, a).

Fig.2. Specific features of the composition of olivine (a), orthopyroxene (b), clinopyroxene (c) and garnet (d) from diamondiferous lherzolite G1-3 of the V.Grib kimberlite pipe in comparison with peridotites of the V.Grib pipe [22], diamondiferous peridotites from kimberlite pipes of Canada [4, 5] and South Africa [21, 23], from the Udachnaya kimberlite pipe (Russia [6]) and the Argyle lamproite pipe (Australia [7]), inclusions in diamonds of the world [1, 18] and the ADP [8, 10, 11]. CaO/Cr2O3 diagram for garnets [24] with additional fields from [25]

HzDA/G10D – harzburgite-dunites of the “diamond association”; Hz/G10 – harzburgite-dunites; Lz/G9 – lherzolites; Wh/G12 – wehrlites; E/G3 – eclogites; P/G4 – low-chromium pyroxenites

1 – from phlogopite-garnet lherzolites of the V.Grib pipe; 2 – from garnet lherzolites of the V.Grib pipe

Orthopyroxene is represented by enstatite with Mg# 92.0, which is lower than Mg# values of enstatites from inclusions in diamonds from kimberlite pipes of the M.V.Lomonosov deposit (93.0-94.8 [8]) and diamonds of the harzburgite association of the world (Mg#av 94.2±1.1 [1]) as well as from garnet lherzolites of the V.Grib pipe (92.7-93.7 [22]). However, Mg# corresponds to Mg# values of enstatites from phlogopite-garnet lherzolites of the V.Grib pipe. (91.4-92.9 [22]) as well as diamondiferous peridotites (91.9-94.1 [5, 6, 21]) and inclusions in diamonds of the lherzolite association (92.4±1.9 [1]) (see Fig.2, b). According to the concentrations of TiO2 (0.02 wt.%) and Na2O (0.03 wt.%), enstatite G1-3 corresponds to the field of the “diamond association” (TiO2 ≤ 0.06 wt.%, Na2O ≤ 0.16 wt.% [1]).

Fig.3. TiO2 to Mg# (a) and FeO to MgO (b) ratios in Cr-pyrope from diamondiferous lherzolite G1-3 of the V.Grib kimberlite pipe in comparison with peridotites of the V.Grib kimberlite pipe [22] and inclusions in diamonds [1, 8]

Table 2

Concentrations of rare elements in Cr-diopside from lherzolite G1-3, ppm

|

Element |

Number of Cr-diopside grain |

||||||||

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

|

|

Sc |

22.2 |

19.6 |

23.6 |

22.1 |

20.3 |

19.9 |

19.6 |

19.0 |

20.8 |

|

Ti |

309 |

256 |

374 |

377 |

280 |

283 |

321 |

260 |

260 |

|

V |

321.2 |

269.4 |

316.3 |

306.8 |

326.1 |

316.5 |

296.6 |

306.5 |

333.3 |

|

Cr |

8069 |

6627 |

8078 |

7610 |

7922 |

7927 |

7378 |

7725 |

8381 |

|

Mn |

391.1 |

373.1 |

413.2 |

429.4 |

409.9 |

436.8 |

422.7 |

412.3 |

425.3 |

|

Co |

16.5 |

15.4 |

16.5 |

17.7 |

17.7 |

18.8 |

17.7 |

17.8 |

17.4 |

|

Ni |

265.2 |

262.8 |

261.3 |

275.0 |

305.8 |

309.3 |

307.5 |

305.8 |

299.3 |

|

Sr |

29.72 |

7.77 |

61.11 |

30.21 |

16.71 |

17.84 |

40.66 |

6.57 |

13.14 |

|

Y |

0.646 |

0.631 |

0.718 |

0.637 |

0.520 |

0.580 |

0.708 |

0.583 |

0.537 |

|

Zr |

1.023 |

0.461 |

1.854 |

1.597 |

0.719 |

0.774 |

1.635 |

0.467 |

0.633 |

|

Nb |

0.543 |

0.087 |

1.295 |

0.668 |

0.419 |

0.449 |

0.747 |

0.062 |

0.565 |

|

Ba |

9.92 |

0.37 |

20.62 |

18.19 |

6.27 |

8.03 |

13.27 |

0.11 |

3.24 |

|

La |

1.150 |

0.407 |

1.658 |

1.059 |

0.761 |

0.573 |

1.348 |

0.390 |

0.665 |

|

Ce |

1.729 |

0.767 |

2.834 |

2.069 |

1.330 |

1.116 |

2.511 |

0.667 |

1.113 |

|

Pr |

0.172 |

0.068 |

0.321 |

0.231 |

0.137 |

0.118 |

0.254 |

0.064 |

0.093 |

|

Nd |

0.599 |

0.229 |

1.135 |

0.901 |

0.441 |

0.369 |

1.018 |

0.212 |

0.404 |

|

Sm |

0.15 |

0.12 |

0.19 |

0.23 |

0.17 |

0.15 |

0.20 |

0.14 |

0.12 |

|

Eu |

0.072 |

0.055 |

0.086 |

0.073 |

0.059 |

0.057 |

0.073 |

0.053 |

0.053 |

|

Gd |

0.225 |

0.251 |

0.306 |

0.196 |

0.181 |

0.187 |

0.269 |

0.157 |

0.176 |

|

Tb |

0.033 |

0.035 |

0.041 |

0.035 |

0.034 |

0.025 |

0.037 |

0.034 |

0.029 |

|

Dy |

0.209 |

0.193 |

0.219 |

0.181 |

0.150 |

0.172 |

0.157 |

0.148 |

0.135 |

|

Ho |

0.029 |

0.024 |

0.041 |

0.027 |

0.026 |

0.023 |

0.031 |

0.024 |

0.024 |

|

Er |

0.062 |

0.057 |

0.058 |

0.055 |

0.042 |

0.034 |

0.054 |

0.044 |

0.033 |

|

Tm |

0.003 |

0.005 |

0.007 |

0.006 |

0.008 |

0.003 |

0.007 |

0.006 |

0.004 |

|

Yb |

0.03 |

0.03 |

0.03 |

0.03 |

0.02 |

0.02 |

0.03 |

0.02 |

0.03 |

|

Lu |

0.002 |

0.004 |

0.003 |

0.002 |

0.007 |

0.001 |

0.005 |

0.002 |

0.002 |

|

Hf |

0.062 |

0.052 |

0.091 |

0.106 |

0.059 |

0.058 |

0.081 |

0.034 |

0.043 |

|

Ta |

0.032 |

0.003 |

0.060 |

0.024 |

0.014 |

0.016 |

0.029 |

0.005 |

0.018 |

|

Th |

0.066 |

0.010 |

0.148 |

0.078 |

0.044 |

0.037 |

0.120 |

0.006 |

0.062 |

|

U |

0.011 |

b.d.l. |

0.029 |

0.019 |

0.013 |

0.008 |

0.019 |

b.d.l. |

0.012 |

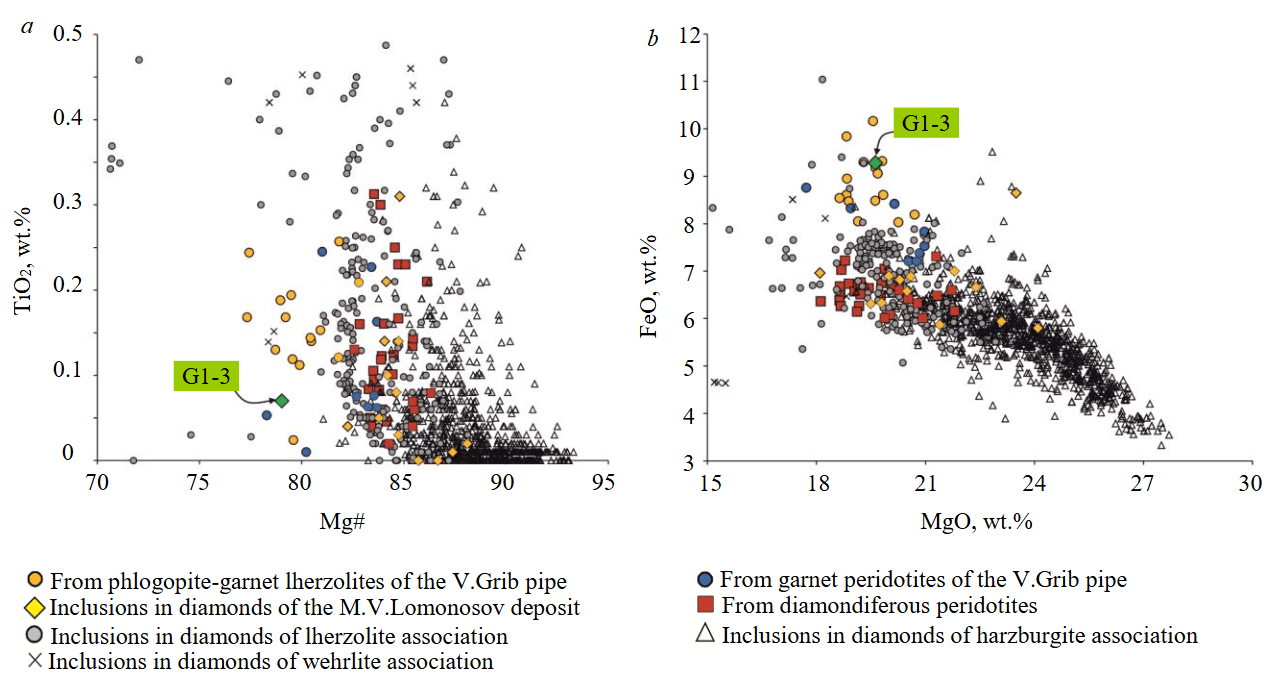

Fig.4. Specific features of rare-earth element composition of Cr-diopside and Cr-pyrope from diamondiferous lherzolite G1-3 of the V.Grib kimberlite pipe: a-e – concentrations of rare-earth elements (a, c) [26] and rare (b, d) elements normalized to chondrite C1; e – Lan/Ybn to Ti/Eu ratios in Cr-diopside; f – Y and Zr content in Cr-pyrope.

Compositions of Cr-pyropes from peridotites of the V.Grib pipe and the Lz-1-1 group [16, 22], diamondiferous peridotites [4, 5, 23], J4 and inclusions in diamonds [1].

EA018 – garnet peridotite of the Ekati pipe (Canada) [5]; VKN – Cr-diopside from inclusions in diamonds of the Venetia (South Africa), Karowe (Botswana) kimberlite pipes and a placer deposit in Namibia [1]; DO40 – diamondiferous lherzolite of the Premier kimberlite pipe (South Africa) [23]; BD3736/1 – Cr-pyrope of exsolved genesis in orthopyroxene megacryst from the Jagersfontein kimberlite (South Africa) [27]. Inclusions in diamonds from Victor (Canada) – VMG327-1, Gacho Kue (Canada) – GK51A, Mwadui (Tanzania) – MW2-5b kimberlite pipes and pre-metasomatic garnet [1]

Clinopyroxene is represented by Cr-diopside (Cr2O3 1.3 wt.%) with Mg# 94.2, which is much higher than that of enstatite in lherzolite G1-3, and also higher than the average Mg# values in Cr-diopsides from inclusions in diamonds (Mg# 92.8) and cratonic lherzolites (Mg# 92.3) [1]. By TiO2 (0.05 wt.%), Cr2O3 concentrations and Mg# values, Cr-diopside G1-3 corresponds to those from both diamondiferous lherzolites and inclusions in diamonds (see Fig.2, c). Cr-diopside G1-3 has higher Al2O3 contents (2.4 wt.%) and lower K2O concentrations (< 0.05 wt.%) compared to Cr-diopsides from both diamondiferous lherzolites (Al2O3 0.8-1.4 wt.%, K2O 0.2-0.4 wt.% [5, 7]), and inclusions in diamonds (Al2O3 0.3-4.8 wt.% [1, 18], Al2O3av 1.4 wt.% [1]; K2O to 1.7 wt.%, K2Oav 0.1 wt.% [1]). Relative to chondrite C1 (Table 2, Fig.4, a, b [26]), Cr-diopside G1-3 is slightly enriched in light (L) rare-earth elements (REE) (< 5 chondrite units (CU); Lan/Ybn = 23) as well as Ba, Sr, Th, U (< 3 CU), depleted in heavy (H) REE (0.8-0.1 CU), Zr-Hf (0.2-0.6 CU) and contains concentrations of medium (M) REE at the level of chondrite C1. Cr-diopside G1-3 is depleted in all REE as well as Sr, Zr and Hf relative to Cr-diopsides from lherzolites of the V.Grib pipe [22], diamondiferous lherzolite of the Ekati kimberlite pipe (Canada) [5] and peridotite J4 (rare element composition of garnet and clinopyroxene in this sample is close to the primitive one [1]). Nevertheless, concentrations of REE close to those of Cr-diopside G1-3 were determined for inclusions of Cr-diopsides in diamonds from the Venetia (South Africa), Karowe (Botswana) kimberlite pipes and a placer deposit in Namibia (Fig.4, a [1]). In the distribution of Lan/Ybn and Ti/Eu, the composition of Cr-diopside G1-3, as well as Cr-diopsides from inclusions in diamonds and peridotite J4, corresponds to the field of silicate metasomatism (Fig.4, e). Cr-diopside G1-3 is characterized by higher values of the Ti/Eu ratio (Fig.4, e), while it contains much lower concentrations of TiO2 compared to Cr-diopsides of the 1st type (LREE 6-27 CU, in equilibrium with silicate melt, Fig.4, a) from lherzolites of the V.Grib pipe (TiO2 0.14-0.23 wt.%).

Garnet is represented by Cr-pyrope, which in terms of Cr2O3 (2.05 wt.%) and CaO (4.7 wt.%) concentrations corresponds to the lherzolite association (see Fig.2, d [24, 25]). Cr-pyrope G1-3 has a low Mg# value (79.0), which is not characteristic of pyropes of both harzburgite and lherzolite associations from inclusions in diamonds and diamondiferous peridotites (see Fig.3, a), but at the same time contains low concentrations of TiO2 (0.07 wt.%). This, in turn, is typical for pyropes from inclusions in diamonds and diamondiferous peridotites, but not characteristic of pyropes from phlogopite-garnet lherzolites of the V.Grib pipe (see Fig.3, a). Cr-pyrope G1-3 contains higher concentrations of FeO (9.3 wt.%) compared to pyropes from diamondiferous peridotites, inclusions in diamonds among them those from the M.V.Lomonosov deposit, but corresponds to those from phlogopite-garnet lherzolites of the V.Grib pipe (see Fig.3, b). Relative to chondrite C1 (Table 3, Fig.4, c, d [26]), Cr-pyrope G1-3 is depleted in high-field strength (HFSE) and large-ion lithophile (LILE) elements, as well as LREE (0.02-0.03 CU), contains MREE at the chondrite level (0.2-2 CU) and is enriched in HREE (3-13 CU). In the distribution of REE normalized to chondrite C1 (Fig.4, c, d [26]), a fractionated spectrum from LREE to HREE is recorded (Lan/Ybn = 0.002; Gdn/Ybn = 0.2). Relative to the composition of garnet J4 [1], Cr-pyrope G1-3 is depleted in all incompatible elements (Fig.4, c, d), but with similar HREE contents. REE distribution spectrum of Cr-pyrope G1-3 is not typical for garnets of both harzburgite, and lherzolite associations from inclusions in diamonds and diamondiferous peridotites, which, as a rule, are characterized by sinusoidal (less often “hump”) REE distribution spectra [1]. However, fractionated (from MREE to HREE) REE spectra similar to Cr-pyrope G1-3 were identified for pyropes from diamondiferous lherzolite of the Premier kimberlite pipe (South Africa) [23] and for pyropes of the lherzolite association from inclusions in diamonds of the Victor, Gacho Kue (Canada) and Mwadui (Tanzania) kimberlite pipes [1] (Fig.4, c, d). Cr-pyrope G1-3 contains low concentrations of Y (11.5 ppm) and Zr (1.2 ppm) typical of Lz-1-1 type garnet xenocrysts from the ADP kimberlite pipes, but different from most garnets from inclusions in diamonds and diamondiferous peridotites, and much lower than garnet J4 (Fig.4, f).

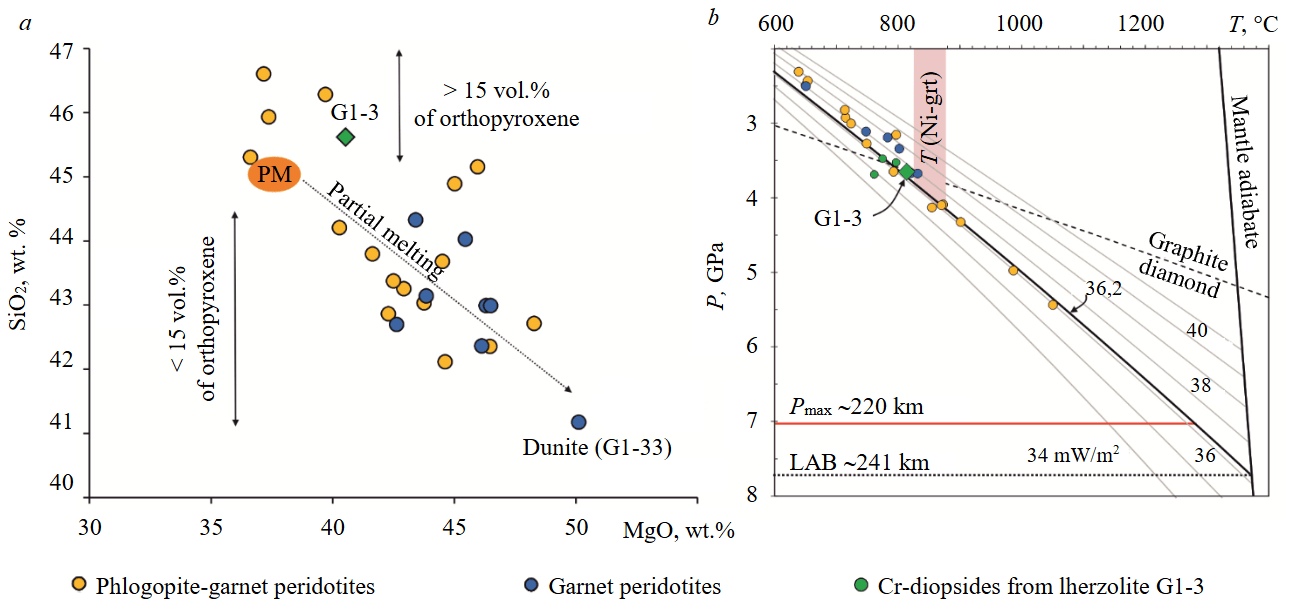

The results of reconstruction of the chemical composition of lherzolite G1-3, based on the modal content of rock-forming minerals and their compositions, are presented in Table 1. The chemical composition of lherzolite G1-3 is identical to the compositions of phlogopite-garnet lherzolites in the V.Grib pipe containing > 15 vol.% orthopyroxene: elevated concentrations of SiO2 (45.3-46.6 wt.%) are characteristic at lower MgO contents (36.6-40.5 wt.%) and Mg# values (89.4-90.6) (Fig.5, a). Compared with composition of the primitive mantle [28], lherzolite G1-3 has slightly higher concentrations of SiO2 and MgO at lower contents of TiO2, Al2O3, and CaO.

Table 3

Concentrations of rare elements in Cr-pyrope from lherzolite G1-3, ppm

|

Element |

Number of Cr-pyrope grain |

|||||||

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

|

|

Sc |

102.4 |

108.7 |

107.3 |

106.6 |

97.46 |

95.30 |

97.84 |

97.10 |

|

Ti |

341 |

348 |

331 |

405 |

366 |

427 |

422 |

404 |

|

V |

130.5 |

129.4 |

122.1 |

145.9 |

142.0 |

161.0 |

166.6 |

169.6 |

|

Cr |

9696 |

9677 |

8940 |

12,235 |

12,012 |

13,405 |

13,483 |

12,809 |

|

Mn |

1300 |

1114 |

1117 |

1154 |

1259 |

1266 |

1415 |

1402 |

|

Co |

41.37 |

39.58 |

39.90 |

44.06 |

46.58 |

49.67 |

51.37 |

52.70 |

|

Ni |

15.21 |

14.30 |

14.61 |

16.34 |

16.93 |

17.87 |

17.68 |

19.20 |

|

Sr |

0.008 |

0.003 |

0.020 |

0.017 |

0.006 |

b.d.l. |

0.008 |

0.004 |

|

Y |

11.87 |

13.33 |

12.08 |

13.26 |

10.39 |

11.12 |

10.37 |

9.60 |

|

Zr |

0.889 |

1.504 |

1.230 |

1.496 |

0.895 |

1.305 |

1.112 |

0.760 |

|

Nb |

0.020 |

0.020 |

0.019 |

0.020 |

0.017 |

0.021 |

0.011 |

0.015 |

|

Ba |

0.02 |

b.d.l. |

b.d.l. |

b.d.l. |

b.d.l. |

b.d.l. |

b.d.l. |

b.d.l. |

|

La |

0.005 |

0.004 |

0.010 |

0.003 |

b.d.l. |

0.004 |

0.001 |

0.002 |

|

Ce |

0.028 |

0.007 |

0.011 |

0.011 |

0.005 |

0.009 |

0.010 |

0.008 |

|

Pr |

0.003 |

0.002 |

0.003 |

0.005 |

0.001 |

0.003 |

0.001 |

0.001 |

|

Nd |

0.012 |

0.009 |

0.033 |

0.047 |

0.009 |

0.037 |

0.031 |

0.013 |

|

Sm |

0.05 |

0.06 |

0.07 |

0.08 |

0.04 |

0.09 |

0.06 |

0.07 |

|

Eu |

0.036 |

0.049 |

0.046 |

0.065 |

0.053 |

0.055 |

0.058 |

0.050 |

|

Gd |

0.45 |

0.51 |

0.42 |

0.47 |

0.34 |

0.44 |

0.39 |

0.32 |

|

Tb |

0.121 |

0.150 |

0.142 |

0.153 |

0.119 |

0.122 |

0.120 |

0.109 |

|

Dy |

1.396 |

1.622 |

1.493 |

1.762 |

1.262 |

1.397 |

1.317 |

1.232 |

|

Ho |

0.381 |

0.497 |

0.441 |

0.439 |

0.375 |

0.396 |

0.374 |

0.319 |

|

Er |

1.480 |

1.720 |

1.588 |

1.730 |

1.364 |

1.405 |

1.341 |

1.200 |

|

Tm |

0.262 |

0.299 |

0.259 |

0.300 |

0.230 |

0.226 |

0.229 |

0.204 |

|

Yb |

1.89 |

2.08 |

2.06 |

2.16 |

1.74 |

1.71 |

1.82 |

1.69 |

|

Lu |

0.340 |

0.376 |

0.319 |

0.388 |

0.302 |

0.317 |

0.290 |

0.257 |

|

Hf |

0.049 |

0.072 |

0.057 |

0.061 |

0.042 |

0.061 |

0.057 |

0.029 |

|

Ta |

b.d.l. |

b.d.l. |

0.002 |

0.006 |

b.d.l. |

b.d.l. |

b.d.l. |

b.d.l. |

|

Th |

b.d.l. |

b.d.l. |

b.d.l. |

0.003 |

b.d.l. |

b.d.l. |

b.d.l. |

b.d.l. |

|

U |

b.d.l. |

b.d.l. |

b.d.l. |

0.007 |

b.d.l. |

b.d.l. |

b.d.l. |

b.d.l. |

To calculate the P-T parameters of the last equilibrium a combination of a thermometer [29] and a barometer [30] was used as well as a monomineral thermobarometer for Cr-diopside [18] and a thermometer for Cr-pyrope [31]. The calculation results are shown in Fig.5, b. The combination [29, 30] showed the result T – 814 °С and P – 3.7 GPa, which corresponds to a depth of ~118 km. The calculation results according to [18] give T values within 775-800 °С and P from 3.5 to 3.7 GPa. T values for Cr-pyrope [31] vary from 830 to 870 °С, which, when projected onto the most optimal (best-fit) geotherm for the lithospheric mantle in the area of the V.Grib pipe (36.2 mW/m2, Fig.5, b [17]), corresponds to P from 3.8 to 4.1 GPa. The obtained P-T values lie near the graphite-diamond phase transition line (Fig.5, b).

Fig.5. Specific features of reconstructed chemical composition (a) and calculated P-T parameters (b) of diamondiferous lherzolite G1-3 from the V.Grib kimberlite pipe. Reconstructed compositions of peridotites from the V.Grib kimberlite pipe according to [21]. Composition of the primitive mantle (PM) according to [28]. Approximation of geotherms according to [17]

LAB – lithosphere-asthenosphere boundary; Pmax – maximum pressure values for xenocrysts of mantle Cr-pyropes and Cr-diopsides in the V.Grib pipe [17]; T (Ni-grt) – range of calculated T values for Cr-pyrope [31]. Black solid line (36.2 mW/m2) shows the optimal calculated (“best-fit”) geotherm for the lithospheric mantle in the V.Grib pipe area [17]

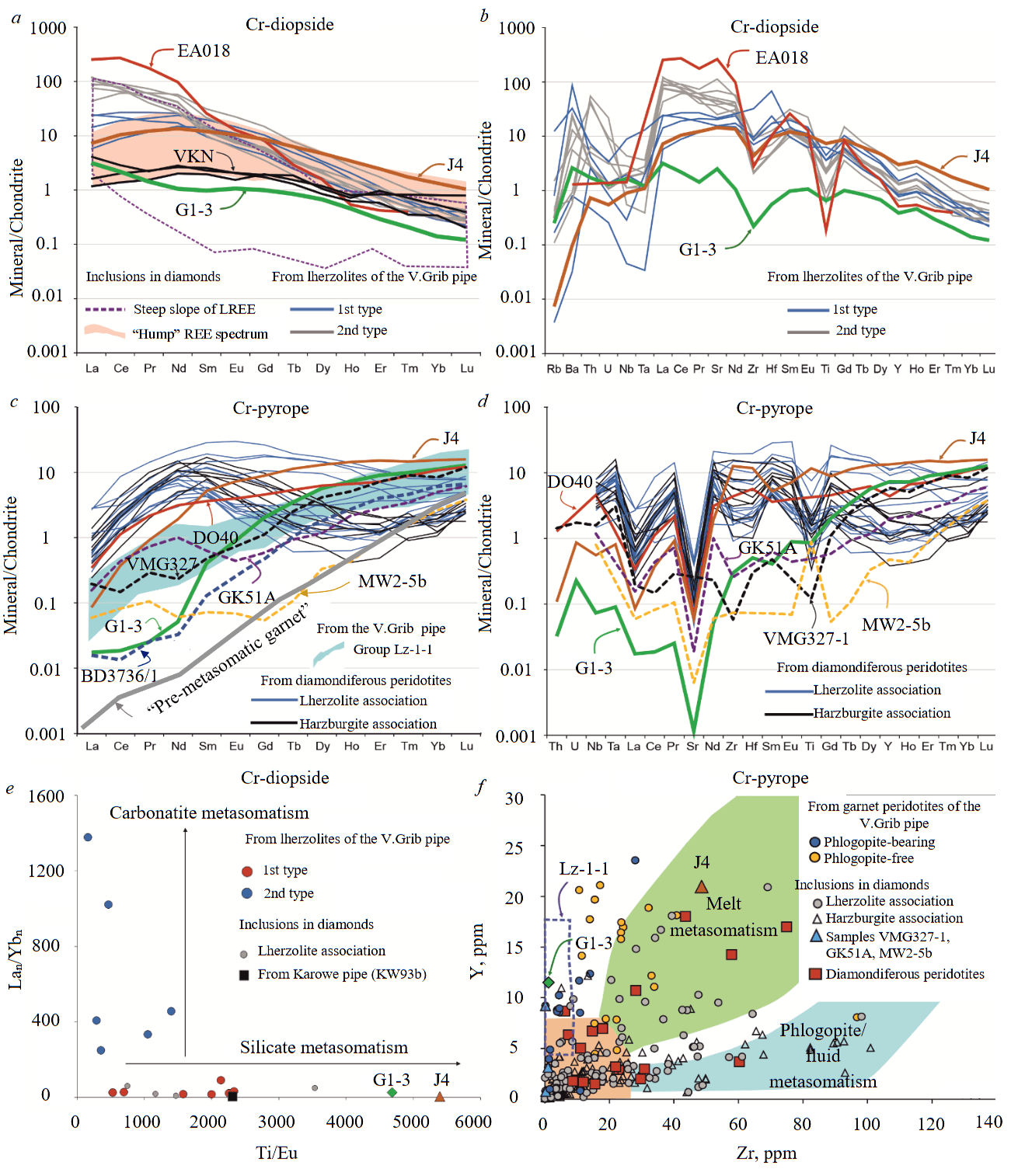

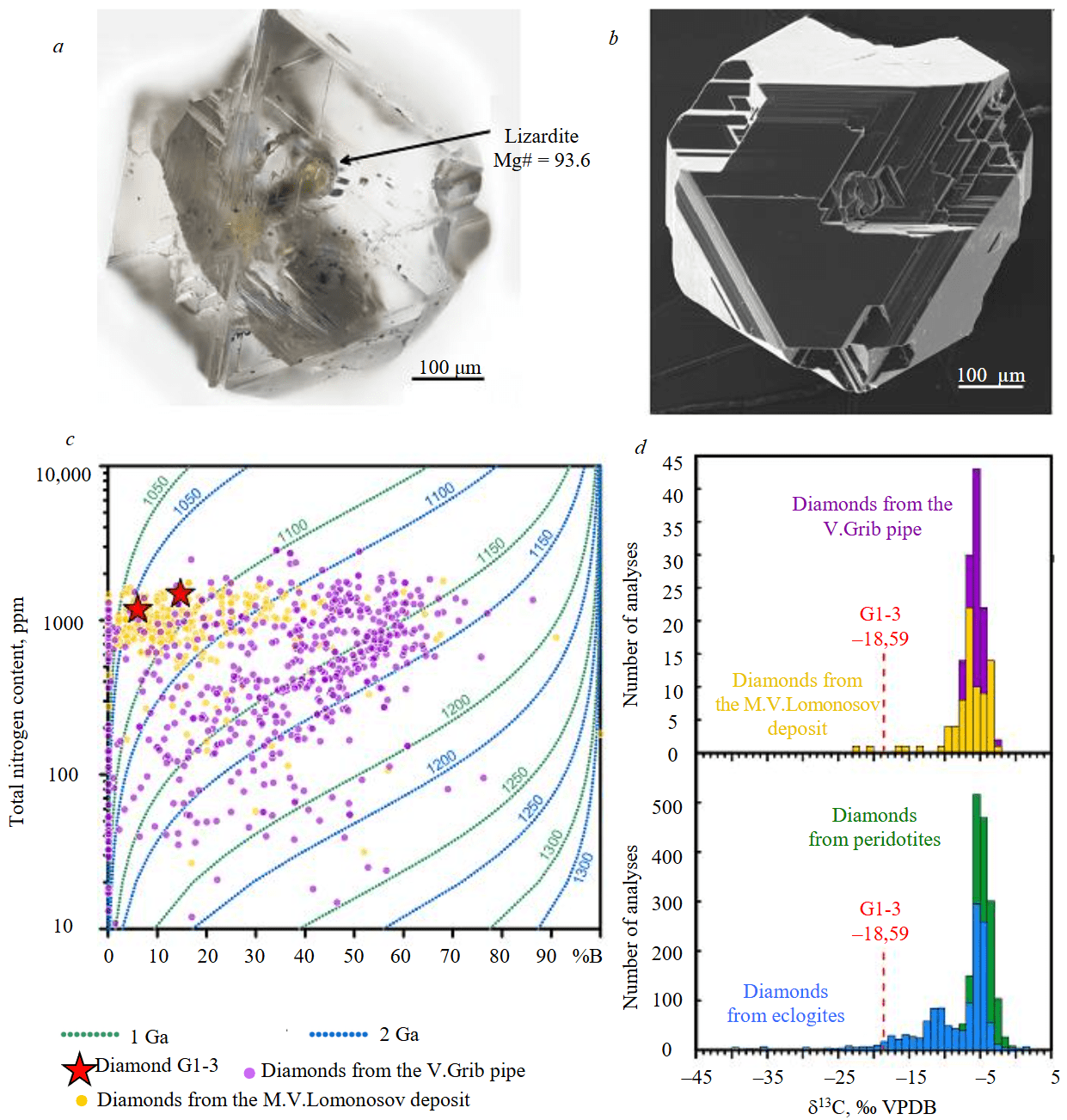

A colourless octahedral diamond measuring ~500 μm was extracted from lherzolite G1-3 (Fig.6, a, b). Rare positively oriented trigonal sculptures are preserved on the flat faces of the octahedron. Octahedron edges are slightly multiplied and form a stepped pattern, some of the vertices are mechanically chipped. According to the defect-impurity composition, the diamond belongs to the most common IaAB type and contains nitrogen in the form of A- and B-defects [32]. Total nitrogen concentration (Ntot) decreases from 1480 to 1170 ppm from the centre to the edge of the crystal, and its aggregation degree (percentage content in the form of highly aggregated defect B: %B = B/(B + A)∙100) diminishes from 15 to 6 %. The available data on the defect-impurity composition of diamonds from the ADP deposits demonstrate wide variations in the aggregation degree and total nitrogen content of crystals in the V.Grib kimberlite pipe (Ntot = 637±534 ppm, %B = 34±20 [10, 12, 14]) and a narrower range of values for diamonds from the M.V.Lomonosov deposit (Ntot = 955±323 ppm, %B = 15±14 [13, 15]). Diamonds similar to G1-3 in Ntot and %B are practically not documented in the V.Grib kimberlite pipe (Fig.6, c), but are widespread in the M.V.Lomonosov deposit. The absorption coefficient of the line 3107 cm–1 of hydrogen-containing defect N3VH in diamond G1-3 is 13.4 and 8.8 cm–1 in the central and edge zones, which is higher than the average values (from 2 to 4 cm–1) determined for diamonds from different ADP kimberlite pipes.

Calculation of the conditions of diamond G1-3 stay in the mantle, based on dependence of aggregation of nitrogen defect centres on annealing time and temperature [33], showed that when choosing an interval of 1-2 Ga, the annealing of diamond G1-3 occurred at temperature 1050-1090 °C (Fig.6, c). Isotope composition of carbon δ13C in diamond G1-3 shows an extremely low value of –18.59 ‰ relative to the VPDB standard (Fig.6 d). The available data on isotope composition of carbon in diamonds from the ADP kimberlite pipes (Fig.6, d) are limited by δ13C values from –22.1 to –2.9 ‰ for the M.V.Lomonosov deposit [34, 35] and from –9.6 to –2.8 ‰ for the V.Grib pipe [10, 12]. The vast majority of measurements lie in the range of middle mantle values from –8 to –3 ‰ [1]. The accumulated global database indicates the existence of a strongly lightened carbon isotope composition in diamonds from eclogites, down to δ13C values below –40 ‰, which is not characteristic for diamonds from peridotites [1]. Rare extremely negative δ13C values from –14 to –26 ‰ were recorded in peridotite diamonds from deposits in the Kalahari Craton (South Africa [1]) and the Siberian Craton (Russia [6]). A greenish secondary inclusion with Mg# 93.6 was found in diamond G1-3, identified using the Raman spectroscopy as lizardite (Fig.6, a). Mg# of this inclusion differs significantly from the rock-forming olivine (Mg# 91.1), but corresponds to Mg# of serpentine present in the rock.

Fig.6. Characteristics of diamond from lherzolite G1-3: a – photo in reflected light; b – image in secondary electron (SE) mode; c – defect-impurity composition; d – isotope composition of carbon. For comparison, diagrams show data on total nitrogen content and aggregation degree of diamonds from the V.Grib [10, 12] and the M.V.Lomonosov deposit [13-15] kimberlite pipes as well as data on isotope composition of carbon in diamonds from the same pipes [10, 12, 34] and other regions of the world [1]. Isotherms are calculated in accordance with equations [33]

Discussion of results

Olivine from lherzolite G1-3 is characterized by some of the lowest Mg# values (91.1) among peridotites of the V.Grib pipe (Mg# 91.3-92.7, with the exception of two phlogopite-garnet lherzolites with Mg# 91.0 [22]). Mg# values of olivine suggest a degree of melting ≤ 20 % at pressure ~3 GPa [36], however, cumulative data on modal amount of enstatite of 18 vol.% with FeO concentration 7.5 wt.% and MgO/SiO2 ratio 0.89 for lherzolite G1-3 confirms its relationship with orthopyroxene-enriched lherzolites [37]. This, in turn, excludes its single-stage formation from a primitive mantle source and suggests a possibility of adding enstatite both before and after partial melting [37].

Low Mg# values of olivine from lherzolite G1-3 can also be related to enrichment of initially depleted peridotite in FeO as a result of high-temperature melt metasomatism [36, 37]. In this case, true Mg# values of olivine, reflecting the degree of melting, will be hidden, and the obtained Mg# values can falsely reflect a less depleted character of restite. Olivines from inclusions in diamonds in the V.Grib pipe are characterized by higher Mg# values (92.1-93.9), which indicates a more depleted character of peridotites, which are substrates for diamonds (minimum ~40 % at 3 GPa and from ~30 % to ~50 % at 7 GPa). However, in terms of concentrations of major elements and Mg# values, olivine from diamondiferous lherzolite G1-3 corresponds to olivines from both inclusions in diamonds of the lherzolite association and from cratonic lherzolites (see Fig.2 a, b). At the paragenesis level, this points to the same depletion history of lherzolites, a substrate for diamonds, and diamond-free lherzolites. Analysis and interpretation of data on the composition of olivines from inclusions in diamonds and cratonic lherzolites [1, 38] excludes large-scale manifestations of Fe metasomatism in the lithospheric mantle of cratons during its evolution after the stages of diamond formation, but allows for local manifestations of metasomatism as a result of the impact of small portions of melt or fluid, including the possibility of shifts in Mg# values in olivine. One manifestation of this type of metasomatism is the infiltration of protokimberlite melts [36]. This type of enrichment of peridotites is confirmed by the presence of variations in the concentrations of NiO in olivines and Mg# values (including a decrease in Mg# below 90) as well as chemistry nonequilibrium between the rock-forming minerals [36], which is not recorded in lherzolite G1-3. Rock-forming minerals of lherzolite G1-3 are homogeneous in composition, and NiO contents in olivine correspond to the contents in peridotites of the V.Grib pipe, which have a higher magnesium olivine (see Fig.2, a).

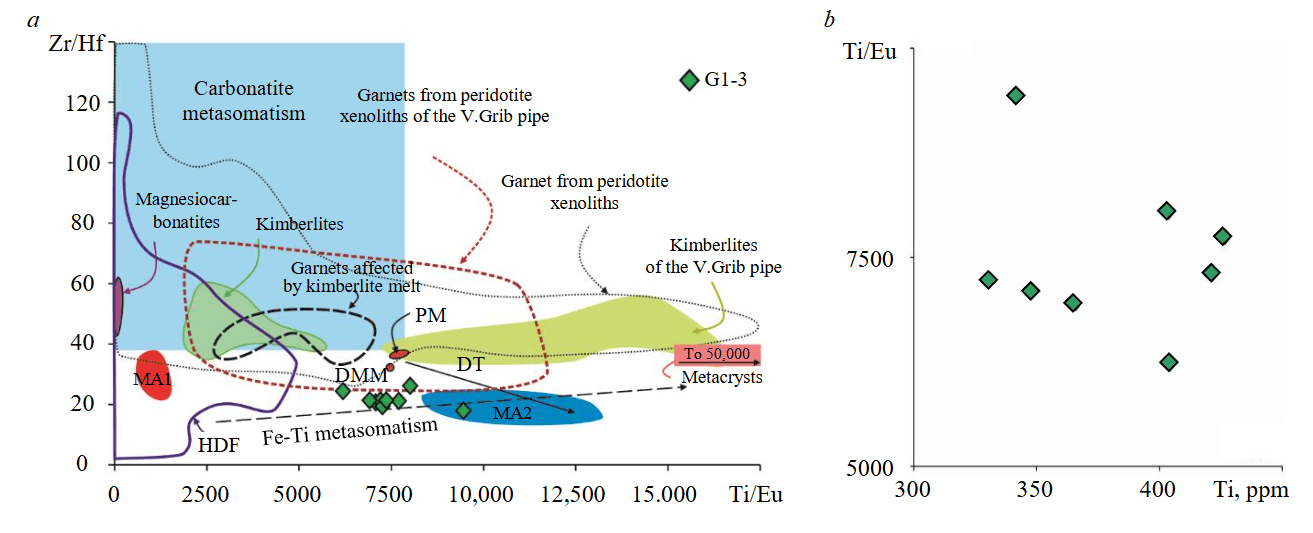

The influence of high-temperature melt metasomatism should, doubtless, be reflected first of all in the composition of Cr-pyrope, namely, in the enrichment in TiO2, Y and Zr [36]. Cr-pyrope of lherzolite G1-3 contains low concentrations of TiO2 (0.07 wt.%), Y (11.5 ppm) and Zr (1.2 ppm), which does not correspond to the compositions of garnets affected by melt metasomatism [1, 36]. Low values of Zr/Y (0.1) and Zr/Hf (21.4) ratios in Cr-pyrope (see Fig.4, f, 7, a [1]) together with low values of Lan/Ybn (26) at high Ti/Eu (4686) in Cr-diopside (see Fig.4, e) also exclude the influence of carbonatite type of mantle metasomatism.

Zr/Hf to Ti/Eu (7400) ratios in Cr pyrope G1-3 do not correspond to the values determined for garnets affected by carbonate-silicate (kimberlite) melt (Zr/Hf 30-50 at Ti/Eu 2500-7000). In Zr/Hf to Ti/Eu diagram, the position of points of all analysed grains of Cr pyropes from lherzolite G1-3 marks areas both near the Fe-Ti metasomatism trend and parallel to the melt depletion trend (Fig.7, a). The absence of an obvious positive correlation between the values of Ti/Eu ratios and Ti contents in Cr pyropes G1-3 (Fig.7, b) as well as low Ti concentrations, do not allow to conclude that Fe-Ti metasomatism was involved [39, 40].

Fig.7. Zr/Hf to Ti/Eu (a) and Ti/Eu to Ti (b) ratios in all analysed grains of Cr-pyrope in diamondiferous lherzolite G1-3. Fields and trends according to [1]; kimberlites of the V.Grib pipe according to [16]; garnets from peridotites of the V.Grib pipe according to [22]; megacrysts of the V.Grib pipe according to [16]; garnets affected by kimberlite melt according to [41].

HDF [42]: DT – partial melting trend. MA – calculated composition of metasomatic agent in equilibrium with composition of Cr-pyrope in lherzolite G1-3: MA1 – distribution coefficient [43], MA2 – distribution coefficient [44]

A distinctive feature of Cr-pyrope G1-3 is the depletion of all incompatible elements relative to garnet of primitive composition J4, depletion of LREE, MREE, HFSE and LILE relative to chondrite C1 and preservation of the fractionated spectrum from LREE to HREE, which is a sign of restitic nature of garnet, i.e. pyrope can be characterized as depleted [1, 27, 41]. Cr-pyropes of this type are rarely found as inclusions in diamonds (see Fig.4, c, d) and, similar to Cr-pyrope G1-3, have low concentrations of Zr (≤ 1 ppm) and Y (≤ 10 ppm). Based on concentrations of TiO2, CaO, Cr2O3, Zr, Y and REE, Cr-pyrope G1-3 corresponds to Cr-pyrope of exsolved genesis in the orthopyroxene megacryst of the Jagersfontein kimberlite pipe captured by kimberlite from a depth of ~90 km, and to Cr-pyrope from an inclusion in diamond of the Victor kimberlite pipe (see Fig.4, c, d). The REE distribution spectrum of these garnets is very close to that calculated for the hypothetical “pre-metasomatic” garnet, but differs from it by elevated REE concentrations (see Fig.4, c), which does not allow to assert the absolute absence of signs of the influence of mantle metasomatism on Cr-pyrope G1-3. According to [41], enrichment of the “pre-metasomatic” garnet in LREE (to 0.02-1.2 CU) with preservation of fractionation in the MREE-HREE region is possible with addition of ≤ 1 % of melt of carbonatite composition ((Sm/La)n from 6 to 20, (Gd/Sm)n ~ 1 [41]) or a minimal amount (< 0.00003 %) of high-magnesium carbonatite fluid ((Sm/La)n ~ 4, (Gd/Sm)n ~ 0.9 [27]), which, however, does not correspond to the composition of Cr-pyrope G1-3 ((Sm/La)n av. ~24, (Gd/Sm)n av ~5, see Fig.4, c).

The calculated values of Zr/Hf (16-23) and Ti/Eu (9000-13,000) in the composition of the hypothetical metasomatic agent in equilibrium with Cr-pyrope G1-3, using the distribution coefficient for garnet with basaltic melt at 2-3 GPa (KD [44]), do not correspond to the values of any natural melt (Fig.7, a). The calculated ratios of Zr/Hf (28-35) and Zr (< 2 ppm) for the composition of the metasomatic agent (KD [43]), in equilibrium with Cr-pyrope G1-3, correspond to both magnesiocarbonate and silicate high-density fluids (HDF) and silicate fluids [42, 45]. The calculated Zr/Hf (28-35) and Ti/Eu (870-1330) values for the composition of metasomatic agent (KD [43]) also correspond to the values for HDF (Fig.7, a). Considering the absence of Fe-Ti metasomatism signs in the composition of Cr-pyrope G1-3, the trend reflecting its metasomatic transformation by Zr/Hf to Ti/Eu is opposite to that of Fe-Ti metasomatism (Fig.7, a) and can reflect a low degree of partial melting of peridotite with preservation of Cr-pyrope and Cr-diopside, as well as subsequent metasomatic enrichment in fluid with a high LREE/HREE ratio. This model agrees with Mg# data for olivine, which suggests a melting degree ≤ 20 % at pressure ~3 GPa [36].

It is known that HDF is capable of efficiently transporting carbon and leading to diamond crystallization when interacting with different mantle rocks [42]. The main sources of information on the composition and origin of HDF are fibrous diamonds, the formation of which is associated with both pre-kimberlite and more ancient metasomatic events [42]. The degree of nitrogen aggregation (%B from 6 to 15) of diamond G1-3 indicates a long stay in mantle conditions, which excludes formation immediately before the emplacement of kimberlite. Extremely light values of isotope composition of carbon (δ13C = –18.59 ‰) indicate the involvement of organic carbon of subduction nature in diamond formation [1]. The study of microinclusions in diamonds from the V.Grib kimberlite pipe showed that both high-Mg carbonatite and low-Mg carbonate-silicate HDF could be diamond-generating environments [46]. Experimental studies link the origin of low-Mg carbonate and silicate HDF with partial melting of eclogites and subduction sediments with different H2O and CO2 ratios [42]. In this regard, the growth of diamond G1-3 could be associated with an ancient metasomatic event that occurred with the leading role of low-Mg silicate-carbonate HDF, the source of which were eclogites and/or subducted sediments containing organic carbon. In this case, the interaction of such HDF with lherzolite G1-3 also led to a slight enrichment of Cr-pyrope in LREE and a change in Zr/Hf and Ti/Eu ratios.

Enrichment of cratonic peridotites in orthopyroxene can be due to the influence of: subduction-related melts or fluids, including those formed by melting of eclogites; SiO2-enriched melts formed by melting of harzburgites; during reaction with komatiite melt at pressures > 4 GPa [1, 47]. In case of lherzolite G1-3, there is no clear evidence in favour of any of the above models, since Cr-pyrope and Cr-diopside do not have/did not retain signs of the influence of melt mantle metasomatism. Experimental data [48] indicate that water-saturated silicate melts as well as water-rich fluid phases containing minor amounts of dissolved silicate or oxide, can be an environment for diamond nucleation and growth. However, the stability limit of diamond in peridotites is determined by the buffer reaction enstatite + magnesite = forsterite + diamond/graphite [48], which, probably, indicates that the processes of diamond formation are separated from the enrichment of lherzolite G1-3 in orthopyroxene. Thus, diamond formation could occur after the stage of lherzolite enrichment in orthopyroxene before the episode of partial melting, but evidence for this period of evolution/transformation was not preserved in the rock. In this case, the fact of diamond preservation in lherzolite G1-3 would argue against the effect of high-temperature silicate melt on the rock after the stage of diamond formation, since this would inevitably result in dissolution [48-50].

The calculated P-T parameters of the last equilibrium of mineral phases of lherzolite G1-3 point to the capture of xenolith by kimberlite from a depth of ~118 km, which corresponds to the depth interval (approximately 95-120 km) from which mantle xenoliths that have signs of the influence of subduction-related fluid were captured [46] including zircon-bearing eclogites forming at the stage of Paleoproterozoic (1.9-1.7 Ga) subduction. This allows assuming that rocks in this section of lithospheric mantle underwent specific local transformations with the leading role of subduction-related fluids of low-Mg carbonate and silicate composition.

Conclusion

This study provided the first data on the composition of rock-forming minerals, including concentrations of rare elements in Cr-pyrope and Cr-diopside, of diamondiferous lherzolite G1-3 from the V.Grib kimberlite pipe, as well as the defect-impurity and isotope compositions of carbon in diamond extracted from lherzolite.

Analysis of major element data for olivine, orthopyroxene, Cr-pyrope, and Cr-diopside from diamondiferous lherzolite G1-3 showed that the composition of these rock-forming minerals corresponds to minerals from both inclusions in diamonds of the lherzolite association and from diamondiferous lherzolites. However, the concentrations of rare and rare-earth elements in Cr-pyrope and Cr-diopside are the same as for lherzolite G1-3, and the nature of their chondrite-normalized distribution spectra were found to date in a very limited number of inclusions in diamonds.

Mg# values of olivine suggest a degree of melting ≤ 20 % at pressure ~3 GPa for the studied lherzolite. Relative to peridotite J4, Cr-diopside G1-3 is depleted in REE, Sr, Zr and Hf, and Cr-pyrope is depleted in all incompatible elements, which, taking into account the presence of a fractionated distribution spectrum from LREE to HREE in Cr-pyrope, allows asserting that lherzolite G1-3 retained signs of partial melting at the time of capture by kimberlite. Nevertheless, elevated REE concentrations in Cr-pyrope G1-3 relative to the composition of hypothetical “pre-metasomatic” garnet do not allow asserting an absolute absence of signs of the influence of mantle metasomatism on Cr-pyrope G1-3. Considering low concentrations of TiO2 (0.07 wt.%), Y (11.5 ppm), Zr (1.2 ppm) and low values of Zr/Y (0.1) and Zr/Hf (21.4) ratios in Cr-pyrope, as well as low values of Lan/Ybn (26) in Cr-diopside G1-3 and calculated values of Zr/Hf and Ti/Eu for the composition of the hypothetical metasomatic agent in equilibrium with Cr-pyrope G1-3, magnesiocarbonate and silicate high-density fluids (HDF) can be assumed as the metasomatic agent that affected lherzolite.

The degree of nitrogen aggregation (%B from 6 to 15) of diamond G1-3 indicates its long stay in mantle conditions, which excludes formation shortly before kimberlite emplacement. Extremely light values of carbon isotope composition (δ13C = –18.59 ‰) indicate the involvement of organic carbon of subduction nature in diamond formation. It was established that formation of diamond G1-3 could be associated with an ancient metasomatic event, which occurred with the leading role of low-Mg silicate-carbonate HDF, the source of which were eclogites and/or subducted sedimentary deposits containing organic carbon. In this case, diamond growth and metasomatic enrichment of Cr-pyrope and Cr-diopside occurred within a single stage.

Elevated modal amount of enstatite (18 vol.%), FeO concentration (7.5 wt.%) and MgO/SiO2 ratio (0.89) for lherzolite G1-3 confirm its association with orthopyroxene-rich lherzolites. Orthopyroxene enrichment could be associated with the influence of subduction-related melts or fluids and SiO2-enriched melts. However, Cr-pyrope and Cr-diopside of lherzolite G1-3 did not have/did not retain the signs of the influence of melt mantle metasomatism, and the processes of diamond and orthopyroxene formation were, probably, isolated.

Cumulative result of the present and previous studies allows assuming that rocks of the lithospheric mantle captured by kimberlite of the V.Grib pipe from intervals from ~95 to ~120 km had signs of specific local transformations with the leading role of subduction-related fluids of low-Mg carbonate and silicate composition.

References

- Stachel T., Aulbach S., Harris J.W. Mineral Inclusions in Lithospheric Diamonds. Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry. 2022. Vol. 88, p. 307-391. DOI: 10.2138/rmg.2022.88.06

- Stachel T., Cartigny P., Chacko T., Pearson D.G. Carbon and Nitrogen in Mantle-Derived Diamonds. Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry. 2022. Vol. 88, p. 809-875. DOI: 10.2138/rmg.2022.88.15

- Smit K.V., Timmerman S., Aulbach S. et al. Geochronology of Diamonds. Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry. 2022. Vol. 88, p. 567-636. DOI: 10.2138/rmg.2022.88.11

- Creighton S., Stachel T., McLean H. et al. Diamondiferous peridotitic microxenoliths from the Diavik Diamond Mine, NT. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology. 2008. Vol. 155. Iss. 5, p. 541-554. DOI: 10.1007/s00410-007-0257-x

- Aulbach S., Stachel T., Heaman L.M., Carlson J.A. Microxenoliths from the Slave craton: Archives of diamond formation along fluid conduits. Lithos. 2011. Vol. 126. Iss. 3-4, p. 419-434. DOI: 10.1016/j.lithos.2011.07.012

- Logvinova A.M., Taylor L.A., Fedorova E.N. et al. A unique diamondiferous peridotite xenolith from the Udachnaya kimberlite pipe, Yakutia: role of subduction in diamond formation. Russian Geology and Geophysics. 2015. Vol. 56. N 1-2, p. 306-320. DOI: 10.1016/j.rgg.2015.01.022

- Jaques A.L., O’Neill H.St.C., Smith C.B. et al. Diamondiferous peridotite xenoliths from the Argyle (AK1) lamproite pipe, Western Australia. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology. 1990. Vol. 104. Iss. 3, p. 255-276. DOI: 10.1007/BF00321484

- Sobolev N.V., Yefimova E.S., Reimers L.F. et al. Mineral inclusions in diamonds of the Arkhangelsk kimberlite province. Russian Geology and Geophysics. 1997. Vol. 38. N 2, p. 358-370.

- Garanin V., Garanin K., Kriulina G., Samosorov G. Diamonds from the Arkhangelsk Province, NW Russia. Springer, 2021, p. 248. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-030-35717-7

- Rubanova E.V., Palazhchenko O.V., Garanin V.K. Diamonds from the V.Grib pipe, Arkhangelsk kimberlite province, Russia. Lithos. 2009. Vol. 112. Suppl. 2, p. 880-885. DOI: 10.1016/j.lithos.2009.04.044

- Malkovets V.G., Zedgenizov D.A., Sobolev N.V. et al. Contents of Trace Elements in Olivines from Diamonds and Peridotite Xenoliths of the V.Grib Kimberlite Pipe (Arkhangelsk Diamondiferous Province, Russia). Doklady Earth Sciences. 2011. Vol. 436. Part 2, p. 219-223. DOI: 10.1134/S1028334X1102005X

- Galimov E.M., Palazhchenko O.V., Verichev E.M. et al. Carbon Isotopic Composition of Diamonds from the Archangelsk Diamond Province. Geochemistry International. 2008. Vol. 46. N 10, p. 961-970. DOI: 10.1134/S0016702908100017

- Vasilev E.A., Kriulina G.Yu., Garanin V.K. Thermal history of diamond from Arkhangelskaya and Karpinsky-I kimberlite pipes. Journal of Mining Institute. 2022. Vol. 255, p. 327-336. DOI: 10.31897/PMI.2022.57

- Vasilev E.A., Ustinov V.N., Leshukov S.I. et al. Diamonds from V.Grib kimberlite pipe: Morphology and spectroscopic features. Lithosphere. 2023. Vol. 23. N 4, p. 549-563 (in Russian). DOI: 10.24930/1681-9004-2023-23-4-549-563

- Khachatryan G.K., Anashkina N.E. Ratio of structural impurity distribution in diamond crystals and kimberlite pipe diamond potentiak (case study of Arkhangelsk region and Yakutia). Ores and metals. 2021. N 3, p. 114-130 (in Russian). DOI: 10.47765/0869-5997-2021-10023

- Agasheva E.V., Gudimova A.I., Chervyakovskii V.S., Agashev A.M. Contrasting Diamond Potentials of Kimberlites of the V.Grib and TsNIGRI-Arkhangelskaya Pipes (Arkhangelsk Diamondiferous Province) as a Result of the Different Compositions and Evolution of the Lithospheric Mantle: Data on the Contents of Major and Trace Elements in Garnet Xenocrysts. Russian Geology and Geophysics. 2023. Vol. 64. N 12, p. 1459-1480. DOI: 10.2113/RGG20234569

- Agasheva E., Gudimova A., Malygina E. et al. Thermal State and Thickness of the Lithospheric Mantle Beneath the Northern East-European Platform: Evidence from Clinopyroxene Xenocrysts in Kimberlite Pipes from the Arkhangelsk Region (NW Russia) and Its Applications in Diamond Exploration. Geosciences. 2024. Vol. 14. Iss. 9. N 229. DOI: 10.3390/geosciences14090229

- Nimis P., Preston R., Perritt S.H., Chinn I.L. Diamond’s depth distribution systematics. Lithos. 2020. Vol. 376-377. N 105729. DOI: 10.1016/j.lithos.2020.105729

- Nimis P. Pressure and Temperature Data for Diamonds. Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry. 2022. Vol. 88, p. 533-565. DOI: 10.2138/rmg.2022.88.10

- Boyd S.R., Kiflawi I., Woods G.S. Infrared absorption by the B nitrogen aggregate in diamond. Philosophical Magazine B. 1995. Vol. 72. Iss. 3, p. 351-361. DOI: 10.1080/13642819508239089

- Viljoen K.S., Swash P.M., Otter M.L. et al. Diamondiferous garnet harzburgites from the Finsch kimberlite, Northern Cape, South Africa. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology. 1992. Vol. 110. Iss. 1, p. 133-138. DOI: 10.1007/BF00310887

- Shchukina E.V., Agashev A.M., Kostrovitsky S.I., Pokhilenko N.P. Metasomatic processes in the lithospheric mantle beneath the V.Grib kimberlite pipe (Arkhangelsk diamondiferous province, Russia). Russian Geology and Geophysics. 2015. Vol. 56. N 12, p. 1701-1716. DOI: 10.1016/j.rgg.2015.11.004

- Viljoen K.S., Dobbe R., Smit B. et al. Petrology and geochemistry of a diamondiferous lherzolite from the Premier diamond mine, South Africa. Lithos. 2004. Vol. 77. Iss. 1-4, p. 539-552. DOI: 10.1016/j.lithos.2004.03.023

- Sobolev N.V., Lavrentev Yu.G., Pokhilenko N.P., Usova L.V. Chrome-rich garnets from the kimberlites of Yakutia and their parageneses. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology. 1973. Vol. 40. Iss. 1, p. 39-52. DOI: 10.1007/BF00371762

- Grütter H.S., Gurney J.J., Menzies A.H., Winter F. An updated classification scheme for mantle-derived garnet, for use by diamond explorers. Lithos. 2004. Vol. 77. Iss. 1-4, p. 841-857. DOI: 10.1016/j.lithos.2004.04.012

- McDonough W.F., Sun S.-s. The composition of the Earth. Chemical Geology. 1995. Vol. 120. Iss. 3-4, p. 223-253. DOI: 10.1016/0009-2541(94)00140-4

- Gibson S.A. On the nature and origin of garnet in highly-refractory Archean lithospheric mantle: constraints from garnet exsolved in Kaapvaal craton orthopyroxenes. Mineralogical Magazine. 2017. Vol. 81. Iss. 4, p. 781-809. DOI: 10.1180/minmag.2016.080.158

- White W.M. Geochemistry. Wiley-Blackwell, 2020, p. 960.

- Taylor W.R. An experimental test of some geothermometer and geobarometer formulations for upper mantle peridotites with application to the thermobarometry of fertile lherzolite and garnet websterite. Neues Jahrbuch für Mineralogie. 1998. Vol 172. Iss. 2-3, p. 381-408. DOI: 10.1127/njma/172/1998/381

- Nickel K., Green D.H. Empirical geothermobarometry for garnet peridotites and implications for the nature of the lithosphere, kimberlites and diamonds. Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 1985. Vol. 73. Iss. 1, p. 158-170. DOI: 10.1016/0012-821X(85)90043-3

- Sudholz Z.J., Yaxley G.M., Jaques A.L., Chen J. Ni-in-garnet geothermometry in mantle rocks: a high pressure experimental recalibration between 1100 and 1325 °C. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology. 2021. Vol. 176. Iss. 5. N 32. DOI: 10.1007/s00410-021-01791-8

- Green B.L., Collins A.T., Breeding C.M. Diamond Spectroscopy, Defect Centers, Color, and Treatments. Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry. 2022. Vol. 88, p. 637-688. DOI: 10.2138/rmg.2022.88.12

- Taylor W.R., Canil D., Milledge H.J. Kinetics of Ib to IaA nitrogen aggregation in diamond. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 1996. Vol. 60. Iss. 23, p. 4725-4733. DOI: 10.1016/S0016-7037(96)00302-X

- Galimov Eh.M., Zakharchenko O.D., Maltsev K.A. et al. Isotope composition of carbon in diamonds from kimberlite pipes in Arkhangelsk Region. Geokhimiya. 1994. N 1, p. 67-73 (in Russian).

- Kriulina G.Yu., Garanin V.K., Vasilyev E.A. et al. New Data on the Structure of Diamond Crystals of Cubic Habitus from the Lomonosov Deposit. Moscow University Geology Bulletin. 2012. Vol. 67. N 5, p. 282-288. DOI: 10.3103/S0145875212050055

- Czas J., Pearson D.G., Stachel T. et al. A Palaeoproterozoic diamond-bearing lithospheric mantle root beneath the Archean Sask Craton, Canada. Lithos. 2020. Vol. 356-357. N 105301. DOI: 10.1016/j.lithos.2019.105301

- Reisberg L., Aulbach S. Continental lithospheric mantle. Treatise on Geochemistry. Elsevier, 2025. Vol. 1, p. 773-865. DOI: 10.1016/B978-0-323-99762-1.00079-6

- Pearson D.G., Scott J.M., Jingao Liu et al. Deep continental roots and cratons. Nature. 2021. Vol. 596. Iss. 7871, p. 199-210. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-021-03600-5

- Qiwei Zhang, Morel M.L.A., Jingao Liu et al. Re-healing cratonic mantle lithosphere after the world’s largest igneous intrusion: Constraints from peridotites erupted by the Premier kimberlite, South Africa. Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 2022. Vol. 598. N 117838. DOI: 10.1016/j.epsl.2022.117838

- Heckel C., Woodland A.B., Gibson S.A. Cretaceous thinning of the Kaapvaal craton and diamond resorption: Key insights from a highly-deformed and metasomatized ilmenite-dunite xenolith. Lithos. 2025. Vol. 494-495. N 107901. DOI: 10.1016/j.lithos.2024.107901

- Qiao Shu, Brey G.P. Ancient mantle metasomatism recorded in subcalcic garnet xenocrysts: Temporal links between mantle metasomatism, diamond growth and crustal tectonomagmatism. Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 2015. Vol. 418, p. 27-39. DOI: 10.1016/j.epsl.2015.02.038

- Weiss Y., Czas J., Navon O. Fluid Inclusions in Fibrous Diamonds. Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry. 2022. Vol. 88, p. 475-532. DOI: 10.2138/rmg.2022.88.09

- Dasgupta R., Hirschmann M.M., McDonough W.F. et al. Trace element partitioning between garnet lherzolite and carbonatite at 6.6 and 8.6 GPa with applications to the geochemistry of the mantle and of mantle-derived melts. Chemical Geology. 2009. Vol. 262. Iss. 1-2, p. 57-77. DOI: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2009.02.004

- Johnson K.T.M. Experimental determination of partition coefficients for rare earth and high-field-strength elements between clinopyroxene, garnet, and basaltic melt at high pressures. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology. 1998. Vol. 133. Iss. 1-2, p. 60-68. DOI: 10.1007/s004100050437

- Gibson S.A., McMahon S.C., Day J.A., Dawson J.B. Highly Refractory Lithospheric Mantle beneath the Tanzanian Craton: Evidence from Lashaine Pre-metasomatic Garnet-bearing Peridotites. Journal of Petrology. 2013. Vol. 54. Iss. 8, p. 1503-1546. DOI: 10.1093/petrology/egt020

- Agasheva E.V., Mikhailenko D.S., Korsakov A.V. Association of quartz, Cr-pyrope and Cr-diopside in mantle xenolith in V.Grib kimberlite pipe (northern East European Platform): genetic models. Journal of Mining Institute. 2024. Vol. 268, p. 503-519.

- Tomlinson E.L., Kamber B.S. Depth-dependent peridotite-melt interaction and the origin of variable silica in the cratonic mantle. Nature Communications. 2021. Vol. 12. N 1082. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-021-21343-9

- Luth R.W., Palyanov Yu.N., Bureau H. Experimental Petrology Applied to Natural Diamond Growth. Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry. 2022. Vol. 88, p. 755-808. DOI: 10.2138/rmg.2022.88.14

- Howarth G.H., Kahle B., Janney P.E. et al. Caught in the act: Diamond growth and destruction in the continental lithosphere. Geology. 2023. Vol. 51. N 6, p. 532-536. DOI: 10.1130/G51013.1

- Howarth G.H., Giuliani A., Bussweiler Y. et al. Kimberlite pre-conditioning of the lithospheric mantle and implications for diamond survival: a case study of olivine and mantle xenocrysts from the Koidu mine (Sierra Leone). Mineralium Deposita. 2024. Vol. 60. Iss. 4, p. 677-695. DOI: 10.1007/s00126-024-01312-0