Conditions of chloride crystallization during well-based exploitation of saturated lithium-bearing brines in the southern part of the Siberian Platform

- 1 — Ph.D. Senior Researcher Institute of Volcanology and Seismology, Far Eastern Branch of the RAS ▪ Orcid

- 2 — Ph.D., Dr.Sci. Chief Researcher Institute of Volcanology and Seismology, Far Eastern Branch of the RAS ▪ Orcid ▪ Elibrary ▪ Scopus

- 3 — Ph.D., Dr.Sci. Head of Laboratory Institute of the Earth’s Crust, Siberian Branch of the RAS ▪ Orcid ▪ Elibrary

- 4 — Ph.D. Head of Department Gazprom Invest LLC ▪ Orcid ▪ Elibrary

- 5 — Ph.D. Senior Researcher RN Krasnoyarsk NIPIneft LLC ▪ Orcid ▪ Elibrary

- 6 — Head of Analytical Centre Institute of Volcanology and Seismology, Far Eastern Branch of the RAS ▪ Orcid ▪ Elibrary

- 7 — Junior Researcher Institute of Volcanology and Seismology, Far Eastern Branch of the RAS ▪ Orcid ▪ Elibrary

- 8 — Junior Researcher Institute of Volcanology and Seismology, Far Eastern Branch of the RAS ▪ Orcid ▪ Elibrary

Abstract

We examine crystallization conditions for saturated brines of calcium, potassium, and magnesium chlorides from the Angara‑Lena artesian basin, Siberian Platform. The study focuses on temperatures matching actual thermal conditions in wells of the “Lithium” site at the Kovykta gas‑condensate field. This critical type of lithium‑bearing raw material is classified as hard-to-recover reserves. In most wells (depths to 2.2 km), rock temperatures in the upper geological section remain below 20 °C. During well operation, various salts precipitate from saturated magnesium-calcium chloride brines within the production line. This leads to rapid wellbore clogging and eventual production shutdown. Thermodynamic analysis of phase diagrams reveals that crystallization yields antarcticite CaCl2·6H2O, tachhydrite Mg2CaCl6·12H2O, minor amounts of carnallite KMgCl3·6H2O, bischofite MgCl2·6H2O, and several other chlorides, depending on temperature. At temperatures above 55 °C, salt precipitation becomes negligible. Thermohydrodynamic simulations of a single flowing well under hydrogeological conditions similar to those at the Kovykta area (southern Siberian Platform) demonstrate the feasibility of long-term (1 month to 1 year) exploitation of saturated sodium-chloride and calcium-chloride lithium-bearing brines. Such operations can yield lithium production rates of 31.2 to 4.2 t per well.

Funding

The work was carried out under the topic FWME-2024-0007 “Heat and Mass Transfer, Seismicity, and Mineral Alterations in Hydrothermal and Volcanic Systems: Thermo-Hydrodynamic-Geochemical-Geomechanical Modelling, Applications for Geothermal Resource Assessment and Prediction of Catastrophic Hydrothermal Events, Volcanic Eruptions, and Major Earthquakes” at the IVS FEB RAS. The study used resources provided by the Shared Research Facilities Centre “Kamchatka Centre for Elemental, Mineral, and Isotopic Analysis”.

Introduction

Lithium, a strategically critical element, plays a key role in the manufacture of rechargeable batteries and is also used in nuclear power generation within tritium-based closed cycles; moreover, it has a wide range of other applications. A relatively new industrial type of lithium raw material in Russia is hydromineral resources [1, 2]. These comprise natural solutions of varying concentrations – from brackish thermal waters to highly concentrated brines. They are associated with evaporite formations, prolonged water – rock interaction, large-scale superimposed processes of platform magmatism [3, 4]. During the extraction of hydromineral resources, sudden salt crystallization often occurs inside wellbores, significantly complicating resource development. The aim of this study is to analyse phase diagrams of brine systems, perform thermohydrodynamic simulations to substantiate the feasibility of long-term well operation when extracting lithium‑bearing brines under conditions of limiting saturation, account for the actual temperature distribution along the wellbore, including heat exchange with enclosing rock formations. We examine solutions to test demonstration problems concerning salt deposition (halite NaCl, antarcticite CaCl2·6H2O) during the operation of a single production well in free-flowing mode. The study employs the TOUGH2-EWASG software, extending its application to saturated calcium chloride brines under hydrogeological conditions similar to those of the Kovykta area in the southern part of the Siberian Platform.

The global interest in lithium extraction is evidenced by numerous studies focusing on reserve exploration and assessment, as well as hybrid technologies for recovering lithium from geothermal brines and solutions [5, 6]. Examples include extraction from spent heat-transfer fluids in geothermal wellfields [7]. Technologies for extracting lithium from natural solutions (salars, seawater, and geothermal brines [8, 9]), as well as from industrial brines of the Siberian Platform [10, 11] have recently gained momentum.

Hydromineral lithium raw materials are found in several countries: eastern France [12], the Half‑Moon area in the eastern province of Saudi Arabia [13], Germany (at the Bruchsal geothermal power plant) [14]. Exploration efforts were also conducted in Nevada and the Salton Sea region (California, USA) [15]. Crude lithium ores remain industrially relevant; therefore, they continue to be the subject of scientific and applied research. For instance, to understand the genesis of lithium raw materials, studies investigated tectono-magmatic factors controlling the localization of lithium-fluorine granites in eastern Russia [16-18], as well as the ore-bearing potential of granitoid intrusions [19]. Many researchers observe connections between lithium-rich brines, geothermal manifestations and volcanic activity [20, 21]. The formation mechanism of lithium-bearing brines in the northern Tibetan Plateau involving geothermal fluids is described in the works [22, 23]. In article [24], the authors thoroughly examine the interactions between hydrothermal systems and volcanic structures themselves.

A significant share of global lithium production comes from the Miocene-Quaternary boron-lithium province deposits in South America. However, oil and gas reservoirs, as well as geothermal solutions, may represent an alternative lithium resource to salars and solid rocks [25]. The urgency of re-evaluating lithium reserves [26] in the Lithium Triangle became so high that studies are being conducted using satellite imagery and various geological data to locate ancient salars buried beneath volcanic deposits [27-30]. Issues of lithium transport and accumulation in the salars of the Lithium Triangle are examined in article [30]. Interest in concentrated lithium-bearing ground brines of the Siberian Platform has grown significantly in recent years [2, 31]. In terms of lithium-bearing brine resources, the hydromineral province of the Siberian Platform (including the Irkutsk Region and Western Yakutia) is comparable to deposits in South America, China, and Tibet [31]. From highly concentrated brines, it is possible to extract lithium chloride, carbonate, fluoride, hydroxide [11], and several other elements [32]. Integrated processing of highly mineralized concentrated brines would meet the demand for magnesium and calcium raw materials. Global interest in lithium is increasing, with research covering all aspects – genesis, exploration, reserve assessment, extraction, and develop-ment of pilot and industrial production facilities. To achieve technological sovereignty for Russia, it is necessary to continuously plan for the growth of the lithium mineral resource base, including conducting comprehensive studies of hydromineral raw materials. This would ensure independence from external lithium suppliers and enable domestic lithium extraction. Several challenges and technical issues stand in the way of developing the rich hydromineral lithium resources of the Siberian Platform, one of which is salt crystallization in production line during well extraction of highly mine-ralized concentrated brines. The aim of this study is to apply thermohydrodynamic simulation to estimate the amount of recoverable saturated brine from a typical production well operating in self-flow mode, considering mineral formation caused by heat losses during ascent into the zone of lower temperatures in the enclosing rock formations. The objectives include analysis of the chemical composition of a representative brine sample, analysis of corresponding phase diagrams, demonstration thermohydrodynamic simulation of production well operation using the porosity-permeability and thermophysical parameters of the Kovykta area.

Conditions for the occurrence of highly concentrated and saturated brines

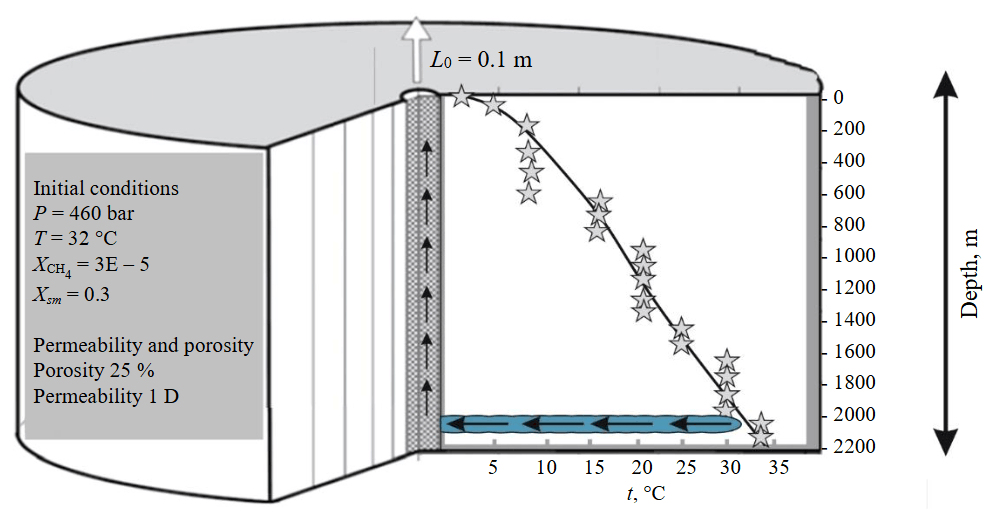

In the Angara‑Lena artesian basin, drilling revealed highly concentrated and saturated industrial brines with very high mineralization (to 630-728 g/l) and high formation pressure (to 400-500 bar) at depths of 1800-2200 m [1, 33, 16]. The anomalously high pressure enables well flowing (Fig.1); however, salt deposition in the casing string (CS) leads to a decline in production rate. Fig.2 shows the temperature profile of the production well versus depth. Over most of the wellbore, the temperature is below 20 °C, and chloride precipitation from supersaturated solutions may occur in an avalanche‑like manner. The temperature gradient is approximately 15 °C/km. The solubility of calcium and magnesium chlorides is strongly temperature-dependent – unlike, for example, the solubility of sodium chloride.

Exploration work in this basin has been ongoing since the 1960s. Currently, the geological exploration project for the “Lithium” subsurface site includes plans to conduct technological studies using a pilot plant for brine extraction and selective lithium recovery. One of the key challenges in lithium extraction is spontaneous salt crystallization in the well casing [1, 2], which leads to reduced

Fig.1. Kovykta area, Angara‑Lena artesian basin: a – controlled free‑flowing of a deep well, “Lithium” site; b – salt plug inside drill pipes – salts crystallize when the system’s PVT conditions are disrupted (photos provided by A.G.Vakhromeev)

Fig.2. Conceptual model of well exploitation of lithium‑bearing extremely saturated brines,Kovykta area, Angara‑Lena basin [31]

A production well in a radial-cylinder (RZ) coordinate system penetrates the target reservoir at a depth of 2 km; on the left – information on the initial conditions in the target reservoir and its porosity and permeability; on the right – a graph of temperature variation with depth (marked by asterisks) in the cap rock of the enclosing formations; arrows – movement of brine from the target reservoir upward through the well; ХСН4 – mass fraction of methane; Хsm – mass fraction of salt in the solution

flow and eventual cessation of lithium‑bearing brine production from wells. This is the primary reason why such raw materials are classified as hard-to-recover reserves. It is observed that salt crystallization, which clogs wells, typically occurs within the wellhead but may initiate at any point where the brine cools to certain temperatures. The high solubility of calcium and magnesium salts – primarily antarcticite CaCl2·6H2O, tachhydrite 2MgCl2·CaCl2·12H2O, and bischofite MgCl2·6H2O – ensures system stability in the reservoir under elevated temperatures 35-40 °C and high reservoir pressure. A decrease in temperature and pressure at the wellhead triggers spontaneous salt crystallization, predominantly of antarcticite with bischofite admixtures.

The Kovykta gas‑condensate field and the pilot site “Lithium” of the project are located in a region with a sharply continental climate, where daily air temperature fluctuations exceed 25 °C. Summers are hot (to 38-43 °C), while winters are cold, often dropping below −45 °C. External daily and seasonal temperature fluctuations have an adverse effect on the chloride system under consideration – the brine-salt system. Permafrost and the low‑temperature zone in the upper interval of the sedimentary cover’s geological section are critical factors in reducing the temperatures of casing strings and production line. Consequently, they also affect the upward flow of hydromineral raw materials – hard-to-recover concentrated brines – during geological exploration and production cycles [2], especially when the flow in the well is halted. When such brines are stored in open basins, the amount of precipitated salts largely depends on ambient temperature [10]. As a preliminary step in brine processing, natural cooling may be applied. This process is accompanied by crystallization and redistribution of elements between crystalline phases and the solution.

Methods for studying the chemical composition of brine and sediment

We examined chloride salt crystallization in the wellbore under temperatures corresponding to the thermal profile of the production line. Future research objectives include unsteady-state chemo-thermohydrodynamic simulations. We analysed the composition of brines from the Kovykta area (the “Lithium” project) to determine lithium content, major mineral elements: sodium, potassium, calcium, magnesium; principal anions: chloride, sulphate, hydrogen carbonate. The brine is highly concentrated; therefore, for analysis it was diluted 200-fold, with high‑precision control of the dilution factor.

A sample for analysis was collected from the mouth of a flowing well in the Kovykta area (the “Lithium” project). Sampling conditions – at an overflow with a high (more than 1000 m3/day) flow rate of controlled well flowing with brine. At room temperature, the brine formed a two-phase mixture, a viscous solution with crystals at the bottom, with the crystals being quantitatively superior to the solution. Homogenization of the two-phase mixture was achieved by gently heating it to approximately 40-50 °C. An aliquot of the resulting liquid was then collected and transferred to a volumetric flask with a total 200-fold dilution. According to the authors, the brine remains virtually unchanged in its chemical composition during flowing until the well is clogged, and the analysed composition reflects that of the saturated brine.

The macrocomponent composition was studied at the Shared Research Facilities Centre “Kamchatka Centre for Elemental, Mineral, and Isotopic Analysis” (IVS FEB RAS). Calcium and magnesium were determined by atomic absorption spectrometry with an uncertainty of 11 %, according to procedure PNDF 14:1:2:4.137-98. Lithium, sodium, potassium, rubidium, and cesium were analysed by flame emission spectrometry with an uncertainty of 10 %, following PNDF 14:1:2:4.138-98, using a Thermo Electron SOLAAR atomic absorption spectrophotometer. Iron was determined via reaction with sulphosalicylic acid: first, the total iron content was determined; then, only iron (III) was measured. Iron (II) was estimated as the difference between total iron and iron (III), following PNDF 14:1:2:4.50-96. Measurements were performed using a Shimadzu UV-Mini-1240 spectrophotometer. Chloride ions were determined by the argentometric method with an uncertainty of 16 %, following PNDF 14:1:2:3.96‑97. Sulphate ions were analysed by the turbidimetric method with an uncertainty of 15 %, following PNDF 14:1:2:159-2000.

The mineral composition of the salt precipitate formed at approximately 20 °C was studied using an X-ray diffractometer MAX XRD 7000 (Shimadzu). The measurement parameters were as follows: goniometer angular range 6-65° 2θ with step size: 0.1° 2θ, scanning speed 2 deg/min (equivalent to a dwell time of 3 s per point), sample rotation speed 30 rpm.

Solubility data for the KCl–MgCl2–CaCl2–H2O system were taken from reference sources on solubility in multicomponent aqueous-salt systems1. The state space of the KCl–MgCl2–CaCl2–H2O system at fixed temperature and pressure is represented by a tetrahedron: vertices correspond to pure components, six edges represent binary subsystems, four faces correspond to ternary subsystems [34-36]. We used solubility data for both binary and ternary subsystems within the KCl–MgCl2––CaCl2–H2O system. Reference sources provide information on solid phase compositions, solution compositions, and temperatures. The reference compositional data were converted to mole fractions. Concentration triangles were then constructed, with the compositions of solid phases and coexisting solutions plotted within specific temperature intervals. Temperature intervals were selected to ensure that no significant phase transitions occurred within each interval.

The effect of pressure on crystallization from brine can be assessed based on the ratio of molar volumes or densities of the coexisting phases. Salt crystals sink in their own saturated solution, so crystallization is accompanied by a decrease in molar volume. An increase in pressure will promote crystallization, while a decrease in pressure, conversely, favours the dissolution of salts. The influence of pressure on the equilibrium between salts and solutions can be neglected, as pressure has little effect on processes in condensed media.

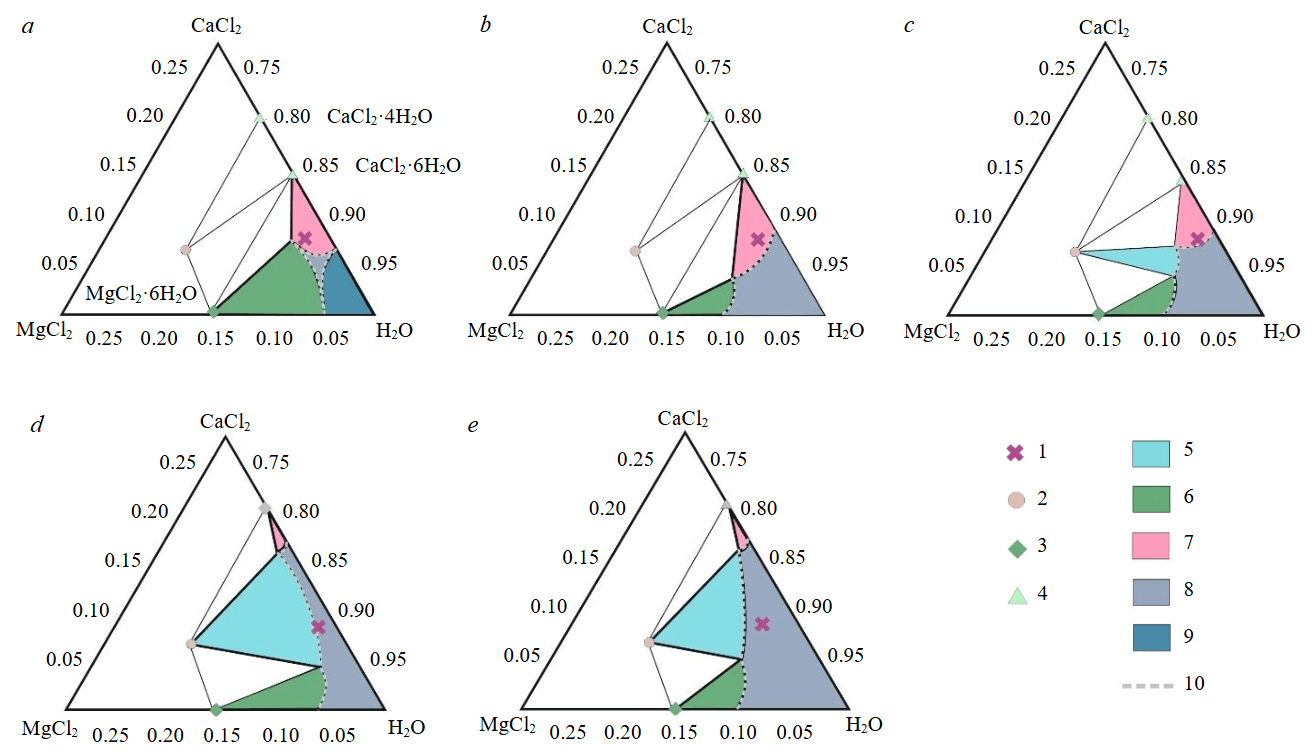

For convenience of presentation, three ternary subsystems were considered, with water as one of the components. Sodium chloride was excluded due to its negligible content in the brine sample under study. To construct quasi‑isothermal sections, data on the composition of solutions coexisting with salt crystals at various temperatures within the studied quaternary system were consolidated. The compositions of solutions and solid phases were expressed in mole fractions, with the following compounds taken as components KCl, MgCl2, CaCl2, and H2O. For simplification, the following ternary subsystems were examined within specific temperature intervals from –35 to 100 °C (rather than true isothermal sections) MgCl2–CaCl2–H2O, KCl–CaCl2–H2O, KCl–MgCl2–H2O. The obtained results were correlated with the actual composition of the brine from the production well to determine the composition of salts that clog the CS depending on temperature. When constructing the three-component MgCl2–CaCl2–H2O subsystem, potassium chloride amounts were chosen not to exceed its content in the brine. Within these limits, potassium chloride does not significantly affect the positions of the tie lines.

The composition triangles were scaled to make the crystallization fields visible in the region adjacent to water. It is necessary to identify conditions under which the figurative point of the brine falls into the liquid field. In this state, salts should not precipitate. If the figurative point of the brine lies on a two‑phase tie line – which represents the equilibrium between salt crystals and solution – the closer this point is to the liquid field, the smaller the amount of salt that precipitates. If the figurative point falls on a two-phase tie line (which represents the equilibrium between salt crystals and solution), the closer the figurative point of the brine is to the liquid field, the less salt precipitates. This is because the phase ratio in equilibrium is determined by the lever rule (or moment rule).

Results of the phase diagram analysis and thermohydrodynamic simulation

Brine composition

The brine is dominated by calcium and magnesium chlorides; potassium and sodium are present in smaller amounts. Due to the presence of trivalent iron, the solution has a brown-orange colour and a relatively low pH, as Fe3+ tends to undergo hydrolysis. After salt precipitation, lithium content in the brine is about 660 mg/l. When converted to LiCl, this corresponds to approximately 4 g of chloride. In addition to lithium, the brine contains rubidium 4.7 mg/l and cesium 13.9 mg/l. When converted to salts, the brine composition is CaCl2 442 g/l, MgCl2 112 g/l, KCl 5 g/l. The main components are calcium and magnesium chlorides, with subordinate amounts of potassium and sodium chlorides. Consequently, we expect the dominant salts to crystallize as various

Fig.3. Diffractogram of the salt precipitate coexisting with the lithium‑bearing brine at a temperature of about 20 °C

1 – salt; 2 – antarcticite; 3 – carnallite

Salt precipitate composition

At 20 °C, the salt precipitate consists primarily of antarcticite (calcium chloride hexahydrate), with only a small amount of carnallite present (Fig.3). Antarcticite crystallizes at temperatures below 30 °C; at higher temperatures, it gradually melts in its own crystallization water; can transform into less hydrated forms – calcium chloride tetrahydrate and dihydrate. Potassium and magnesium salts, as well as their compound carnallite, are less soluble. Carnallite remains stable at the melting temperature of antarcticite and apparently may crystallize inside the wellbore, although its quantity is small for this brine composition. Tachhydrite was not detected by X‑ray diffraction analysis. At approximately 20 °C, the well is likely to become clogged primarily with antarcticite. With a slight temperature increase to 40 °C, the salt precipitate dissolves almost completely, leaving only small amounts of other chlorides as suspended particles.

System KCl–MgCl2–CaCl2–H2O

The positions of the figurative point corresponding to the brine composition were compared with the fields of two‑phase equilibria in sections constructed for various temperature intervals (Fig.4) at a pressure of 1 atm. The hexahydrate CaCl2 · H2O undergoes stepwise dehydration, which involves formation of the dihydrate, release of water, and eventual appearance of a saturated solution (L) of the tetrahydrate and dihydrate. This sequence occurs within a narrow temperature interval of 20-45 °C (see Table). The phase transitions of calcium chloride hexahydrate may proceed via a metastable pathway2.

The KCl–MgCl2–CaCl2–H2O system has about 20 phases, including water and ice. The Table shows the salts that can crystallize from the brine of the studied composition at temperatures from –34 to 100 °C. Calcium and magnesium salts tend to form hydrates with variable amounts of water. As the temperature rises, water is gradually released, and crystal hydrates transform into less hydrated forms. We conventionally denote the crystal hydrates of calcium chloride as an extended region on the CaCl2–H2O edge. Antarcticite transforms into tetrahydrate and dihydrate when heated, and its solubility increases. Magnesium chloride behaves similarly – at low temperatures, the amount of crystallization water reaches 12; as the temperature increases, the dodecahydrate transforms into octahydrate, hexahydrate, and then into tetrahydrate and trihydrate – but this occurs at higher temperatures compared to calcium chloride hydrates. This behaviour is typical for crystal hydrates. A specific feature of calcium and magnesium chlorides may be the nature of the phase transition itself, which occurs via peritectic equilibrium with liquid release and resembles melting in their own crystallization water. For crystal hydrates, as the temperature rises, the field of two-phase equilibria shrinks, and consequently the amount of precipitated salt decreases. It is possible to select conditions under which the amount of precipitated salt will be negligible (not leading to clog formation), or the figurative point of the brine will fall within the liquid field.

Fig.4. Phase relation scheme for the ternary subsystem MgCl2–CaCl2–H2O, with temperature ranges from –35 to 0 °C (a),from 0 to 20 °C (b), from 20 to 30 °C (c), from 30 to 40 °C (d), above 40 °C (e)

1 – composition of the Kovytka brine; 2 – tachhydrite Mg2CaCl6·12H2O; 3 – magnesium chloride hydrates MgCl2·6H2O; 4 – calcium chloride hydrates CaCl2·6H2O; 5-7 – saturated solutions in equilibrium with the precipitate of tachhydrite (5), magnesium chloride hydrates (6), calcium chloride hydrates (7); 8 – region of the liquid solution; 9 – ice in contact with chloride solutions; 10 – line separating the liquid solution region from the two-phase equilibrium regions. The composition is expressed in mole fractions; the composition triangle is scaled; the variety of magnesium and calcium chloride hydrates is not shown [37]

Phases of system KCl–MgCl2–CaCl2–H2O [38]

|

Formula (name) |

Equilibria involving solutions |

t, °C |

|

KMgCl3‧6H2O (carnallite) |

– |

– |

|

MgCl2‧12H2O |

MgCl2‧12H2O ~ 2H2O (ice + L) |

≈ –34 |

|

MgCl2‧12H2O ~ MgCl2‧8H2O + 2H2O (L) |

≈ –17 |

|

|

MgCl2‧8H2O |

MgCl2‧8H2O ~ MgCl2‧6H2O + 2H2O (L) |

≈ –3 |

|

MgCl2‧6H2O (bischofite) |

MgCl2‧6H2O ~ MgCl2‧4H2O + 2H2O (L) |

117 |

|

CaCl2‧6H2O (antarcticite) |

CaCl2‧6H2O ~ CaCl2‧4H2O + 2H2O (L) |

29 |

|

CaCl2‧4H2O (hyaraite) |

CaCl2‧4H2O ~ CaCl2‧2H2O + 2H2O (L) |

45 |

|

Mg2CaCl6‧12H2O (tachhydrite) |

Mg2CaCl6‧12H2O ~ Mg2CaCl6‧6H2O + 6H2O (L) |

>55 |

|

Mg2CaCl6‧6H2O |

– |

– |

In the MgCl2–CaCl2–H2O subsystem, two phases can be distinguished: formation of antarcticite CaCl2‧6H2O and tachhydrite Mg2CaCl6·12H2O. These salts are the most likely to cause wellbore clogging. Antarcticite is a low-temperature phase, stable to approximately 29 °C. Tachhydrite, in turn, is observed at temperatures above 20 °C and replaces antarcticite. Therefore, the temperature regime for operating a production well must account for salt transformations that occur with temperature changes. It should be noted that magnesium exhibits a greater variety of hydrates compared to calcium, due to the higher tendency of the magnesium cation to form complexes. Therefore, at low temperatures, wellbore clogging is expected to involve magnesium chloride hydrates with varying water content and calcium chloride hydrates; at higher temperatures, the wellbore space will primarily be clogged with calcium chloride hydrates or calcium‑magnesium chloride hydrates.

Temperature range –35-0 °C

Within this temperature interval, magnesium and calcium chloride hydrates will crystallize from the brine of the studied composition. The figurative point of the brine lies in the equilibrium region of bischofite with antarcticite (Fig.4, a). This temperature range is relevant for well operation in Siberian winter conditions, when ambient temperatures can drop to –40 °C. As the brine rises to the surface and cools, it will precipitate magnesium and calcium chloride hydrates, as well as carnallite (not shown in Fig. 4, as it belongs to another subsystem). If lithium chloride remains and accumulates in the residual liquid phase, rubidium may substitute for potassium in carnallite, potassium chloride, and other potassium salts, concentrating in the salt precipitate. Such redistribution of target elements during brine phase transitions is important for scientifically grounded technologies of integrated raw material processing.

Temperature range 0-20 °C

Under these conditions, antarcticite crystallizes, as seen in Fig.4, b. The figurative point lies in the two‑phase field CaCl2‧6H2O ~ L in the MgCl2–CaCl2–H2O subsystem, rather far from the solution boundary. The solubilities of the salts under consideration strongly depend on temperature, and with its change, the regions of two‑phase equilibria and the liquidus shift noticeably. Due to the high concentration of calcium chloride in the brine, the precipitation of this mineral may be avalanche‑like. Carnallite will also precipitate, since the content of potassium and magnesium chlorides corresponds to the saturation line for carnallite, which is not shown in Fig.4 due to its belonging to another subsystem. If the brine composition is recalculated for the content of hydrated salts, the concentrations of carnallite, antarcticite, and tachhydrite are 17.7; 871.6 and 303.7 g/l respectively. The amount of carnallite is insignificant compared to antarcticite or tachhydrite.

Temperature range 20-30 °C

Within this temperature interval, calcium chloride hexahydrate (antarcticite) begins to significantly melt in its own crystallization water (Fig.4, c), and the two-phase equilibrium field shrinks. Calcium chloride tetrahydrate starts to precipitate, it is also highly soluble. A narrow field of tachhydrite appears, but the figurative point of the brine lies close to the boundary of the three‑phase tie line tachhydrite – antarcticite – solution, so tachhydrite precipitation is insignificant. Minor amounts of carnallite may also precipitate, as its concentration is close to the carnallite saturation line. Although the solubility of antarcticite increases in this temperature range, the figurative point of the brine lies within the two-phase equilibrium region, extending into the three-phase equilibrium region antarcticite – tachhydrite – solution. Therefore, wellbore clogging remains highly likely.

Temperature range 30-40 °C

In the MgCl2–CaCl2–H2O subsystem, the figurative point of the brine falls into the two‑phase equilibrium field of tachhydrite with the saturated solution Mg2CaCl6·12H2O ~ L. Meanwhile, the crystallization field of calcium chloride tetrahydrate shrinks, which corresponds to an increase in its solubility (Fig.4, d). Tachhydrite replaces antarcticite, which becomes unstable at this temperature, as well as gyarite, which has a narrow two‑phase tie line field. Potassium chloride is not expected to precipitate from the brine of this composition. However, small amounts of carnallite or bischofite may crystallize, since in the KCl–MgCl2–H2O subsystem the brine composition is close to saturation with respect to the precipitation of these minerals.

Temperature range above 40 °C

The figurative point of the brine lies in the region of two-phase equilibrium of tachhydrite with its saturated solution (Fig.4, e); the brine is undersaturated with respect to other chlorides. Since the brine composition lies practically on the boundary of the single-phase region corresponding to the liquid solution and the two‑phase equilibrium line, the amount of precipitated tachhydrite should not be large, as the phase ratio is determined by the lever rule and the mass of the liquid solution must significantly exceed the mass of the precipitated tachhydrite. This temperature range is relatively convenient for operation, since within its limits, clogging of the well casing should not occur due to the small amount of precipitated salt (tachhydrite), as well as the removal of precipitated crystals to the surface. The calculated mixing with hot fresh process water or steam, with batch feeding into the area of the tubing shoe is permissible.

As the temperature rises, the liquid field expands, and the figurative point of the brine enters the single‑phase region of the solution. The same applies to other chlorides: heated brine becomes undersaturated with respect to other salts. This is the most convenient temperature range for operating deep tubed wells, during which no clogging or flow decline should occur.

Thermohydrodynamic simulation of salt deposition during the operation of a production well; fluid state equations

Problem statement, model geometry

The geometry of the radial‑cylindrical RZ‑model is shown in Fig.2. To simulate systems containing saline solutions and non‑condensable gas [38], the TOUGH2 software with the EWASG state module is used.

The initial permeability and porosity correspond to the Znamenskaya area: depth 2 km, thickness 2.5 m, porosity 0.25 (25 %), permeability 1 D, initial pressure 300 bar, temperature 32 °C, mass fraction of СН4 = 3·10–5. At the initial simulation stages, NaCl was specified as the salt, although CaCl2 predominates in real conditions. From a practical standpoint, this was assumed to provide a safety margin when justifying engineering and technology solutions, since sodium chlorides precipitate into the solid phase first. The model temperature of 32 °C, measured at the wellbore bottom, is likely somewhat underestimated, as under such conditions the figurative point is in the coexistence region of tachhydrite and its saturated solution. However, for sodium chloride this simplification is not critical, as its solubility weakly depends on temperature.

In the model, the initial mass fraction of dissolved NaCl is automatically determined by the TOUGH2 software with the EWASG state module under conditions of saturation. Over a wide temperature range, the density and viscosity of saturated solutions of sodium, calcium, and magnesium chlorides are similar. Therefore, in geofiltration estimations, one can rely on the NaCl properties supported in the EWASG state module of the TOUGH2 software. The significant differences between sodium chloride and calcium/magnesium chlorides for simulation purposes are as follows: the solubility of NaCl depends only weakly on temperature; in general, halite has lower solubility compared to magnesium and calcium chlorides.

Simulation of production with cyclic injection of hot water (test problem 1)

This problem does not explicitly account for the wellbore (see Fig.2), and production/injection are defined in the mode of a cyclically operating mass source. The target reservoir is specified as a disc with a thickness of 2.5 m and a radius of 200 m. The computational grid (RZ) consists of 100 adjacent elements (NX = 100) with progressively increasing radius. The cyclic mass source is defined at the centre of the model as follows: injection of fresh water with a flow rate Q and a temperature of 100 °C (enthalpy 419 kJ/kg) in the time ranges [ΔtK, Δt (K + 1)], withdrawal of brine with a flow rate Q in the time ranges [Δt (K + 1), Δt (K + 2)], where ∆t = 1 day, K = 0, 2, 4, … 364. For one day, hot water is injected into the well; then, for one day, fluid is extracted at the same flow rate – and this continues for a year (365 days). Fixed boundary conditions are set at the outer boundary of the model. To improve mixing of the injected water with the formation brine, an elevated value of hydrodispersion (molecular diffusion of 0.001 m2/s) is defined in the model.

The maximum possible flow rate for cyclic withdrawal/injection is determined to be 9.3 kg/s using multivariate simulation, based on the condition of preventing crystallization in the bottomhole zone. The total annual production of NaCl salt in such a model is estimated at 8436.7 t. When converted to lithium, this amounts to 9.6 t, assuming a lithium mass fraction of 0.114 % in the initial brine mineralization.

Simulation of production in self‑flow mode (test problem 2)

This simulation considers heat exchange of the extracted fluid through the walls of a 2000 m deep well with the enclosing rock formations. The model is defined on an RZ computational grid with 100 elements in the radial direction (NX = 100, as in test problem 1) and 101 elements in the depth direction (NZ = 100). The target reservoir is defined in the depth range from 1977.5 to 2000.0 m. Above this interval are impermeable enclosing rocks with a specified temperature distribution. Initial conditions are set for the following main variables: pressure P, temperature T, solid phase saturation SS (volume fraction of solid salt in the pore space), mass fraction of methane XCH4. The initial temperature distribution is specified by equation

where Z is depth, m.

The initial pressure is set according to the hydrostatic law, with a maximum value of 300 bar at a depth of 2 km; SS = 0.01 (which automatically defines a saturated sodium chloride solution), XCH4 = 3.0·10–7 (i.e., the mass fraction of CH4 is low). The production well is defined in self‑flow mode at the wellhead, with a productivity index of 1.0·10–12 m3.

The estimated well productivity over 3 days in this problem is such that the maximum flow rate reaches 7 kg/s, thereafter, the flow stabilizes at 4 kg/s. Wellbore clogging is equivalent to the SS variable reaching a value of 1.0 (100 %). At the time point of 237 days, the solid phase saturation SS reaches 1.0 in the near‑wellhead section – i.e., the wellbore becomes clogged by a salt plug. Thus, the operational lifetime of the well under the conditions specified in the model is limited to 237 days.

Simulation of production in self‑flow mode with account for permeability reduction due to pore space clogging (test problem 3)

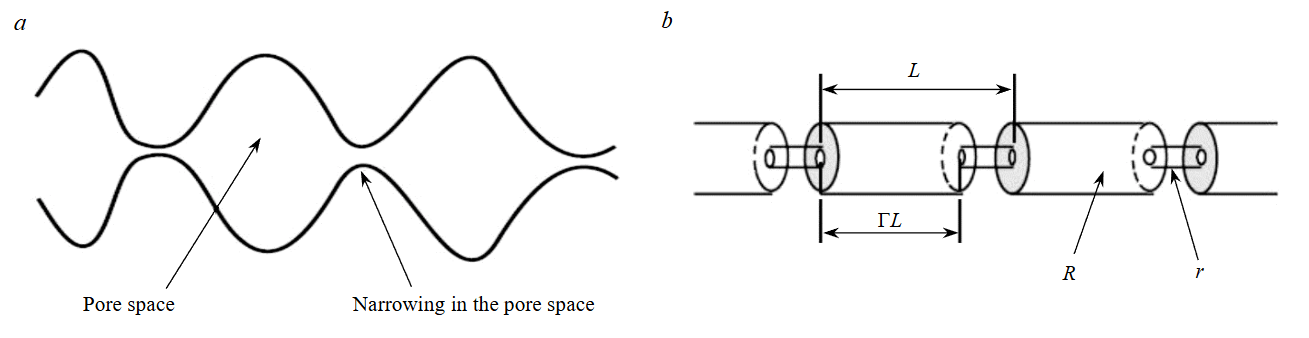

This problem retains the conditions of the previous one but additionally accounts for the reduction of reservoir permeability as the fracture‑pore space becomes filled with crystalline salt. The relationship between the amount of solid phase precipitated from the solution and the change in porosity is rather straightforward. However, the contribution of porosity change to permeability change is more complex. Laboratory experiments show that a small change in porosity can lead to significant changes in permeability. This is explained by the convergent‑divergent nature of pore channels: pore constrictions get sealed by precipitate, while disconnected cavities remain within the pore space [39]. The effects of permeability reduction are determined not only by the overall decrease in porosity, but also by the geometry of the pore space and the distribution of precipitate within it. Such effects can manifest differently in various types of porous media, which creates difficulties in predicting permeability changes due to salt deposition. In EWASG, several options are available for the functional dependence of relative permeability changes k/k0 on the relative change in active porosity ⇔f/⇔0:

where 1 − SS is the fraction of the initial pore space that remains accessible to fluids.

The simplest model representing the convergent‑divergent nature of natural pore channels can be visualized as a sequence of capillary tube segments with larger and smaller radii (Fig.5).

Fig.5. Model for convergent-divergent (compressing-expanding) pore channels:

a – conceptual model; b – series of successive tubes

Although in models of straight capillary tubes the permeability remains non‑zero until porosity reaches zero, in models of tubes with variable channel radii the permeability drops to zero at non‑zero porosity. For the model shown in Fig.5, the following relationship holds [39]:

where the total porosity has the form:

⇔r – the fraction of initial porosity at which permeability drops to zero; Γ – the fraction of the length of porous channels with large radii.

Then the following expression arises:

Thus, equation (1) has only two initial geometric parameters to be determined, – ⇔r and Γ. In the simulation, the above‑described scheme of a series of sequential tubes was adopted to simulate the permeability decline as a function of porosity, with parameter values ⇔r = 0.1, Г = 0.8. Additionally, the well productivity index was increased (compared to test problem 2) to 1.0·10–11 m3, while the wellhead pressure remains unchanged at 1 bar (free flowing).

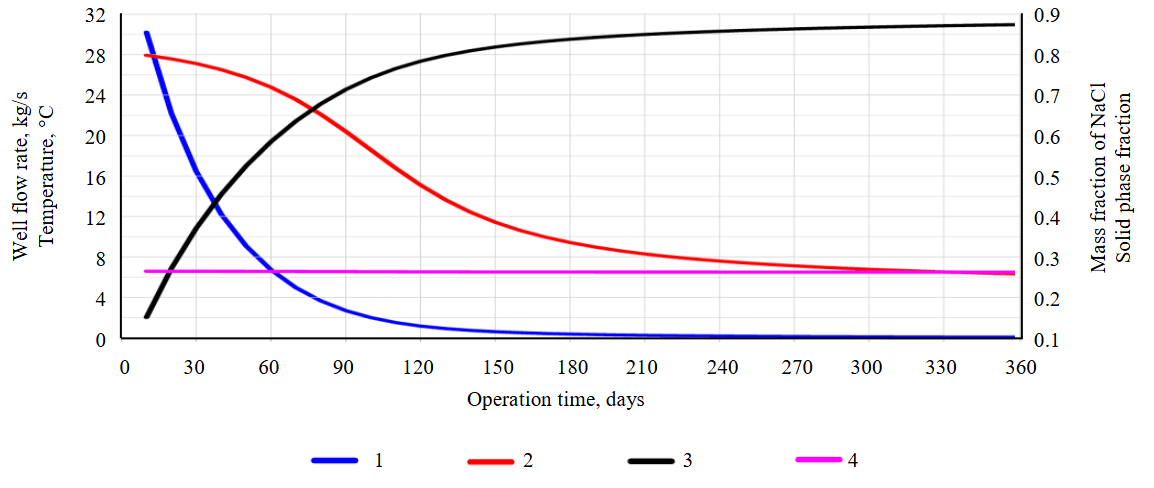

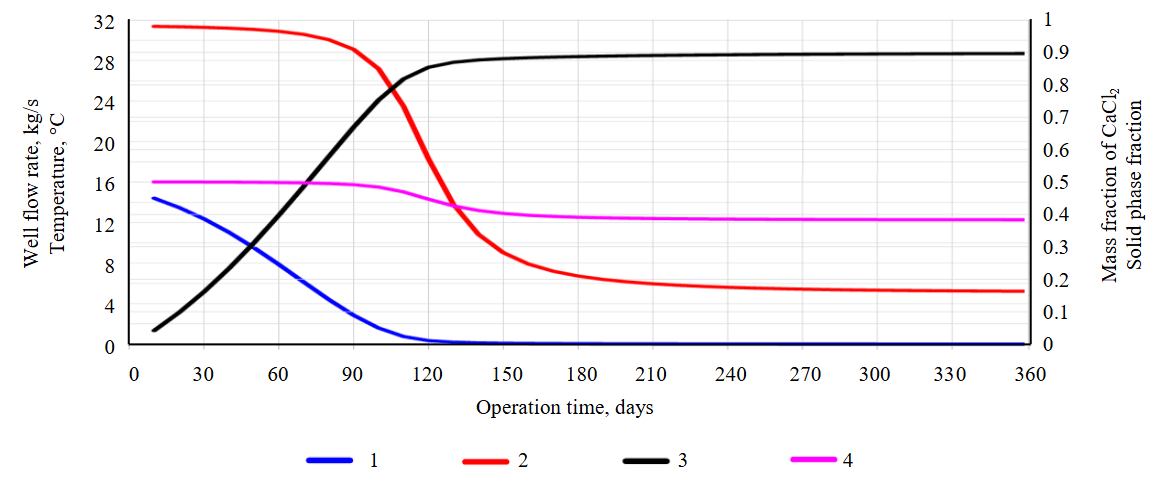

Figure 6 shows the simulation results with the initial parameters: changes in flow rate and wellhead temperature; solid‑phase saturation and NaCl concentration in the wellhead section over a one‑year production period. The dynamics of wellbore filling with solid precipitate at various time points (t = 0, 30, 60, 150, and 360 days) reveals non‑uniform deposition, predominantly in the upper near‑wellhead section. After just one month of operation, the upper part of the well is 50 % clogged, and the flow rate decreases threefold. The total salt production is estimated at 27,387.7 t. When converted to lithium, this amounts to 31.2 t, assuming a lithium mass fraction of 0.114 % in the initial brine mineralization.

Fig.6. Results of TOUGH2‑EWASG simulation of extremely saturated brine extraction (test problem 3)

1 – variation of production well flow rate, kg/s; 2 – wellhead temperature, °C; 3 – volumetric fraction SS of filling the wellbore with NaCl solid phase; 4 – mass fraction of NaCl in the near‑wellhead section of the production well

Fig.7. Results of TOUGH2‑EWASG‑CaCl2 simulation of saturated brine extraction (test problem 4A)

1 – variation of production well flow rate, kg/s; 2 – wellhead temperature, °C; 3 – volumetric fraction SS of filling the wellbore with CaCl2·6H2O solid phase; 4 – mass fraction of CaCl2 in the near‑wellhead section of the production well

Simulation of production in self‑flow mode with account for permeability reduction due to pore space clogging and a calcium chloride composition of the saturated brine (test problems 4, 4A)

Test problem 4 retains the conditions from the previous case (test problem 3). However, the focus shifts to a calcium chloride‑dominated composition of the saturated brine, and the possibility of antarcticite precipitation in the solid phase within both the target reservoir and the wellbore. Consequently, the fluid state module EWASG was programmatically modified to EWASG-CACL2. The solubility of antarcticite as a function of temperature is approximated by the formula

where XEQ – the mass fraction of CaCl2 in the saturated brine; Т – the temperature, °C.

The dependence of the density of the saturated brine DB on the mass fraction of CaCl2 is defined as: DB = 997.55060 + 460.56046 ∙ XEQ + 974.57187 ∙ XEQ2.

Simulation results with the initial parameters show that the well flow rate catastrophically drops from 2 kg/s to zero within the first week of operation, and the wellhead section becomes filled with antarcticite. The total production of CaCl2 is low, amounting to 207.6 t. When converted to lithium, this equals 237 kg, assuming a lithium mass fraction of 0.114 % in the initial brine mineralization. Therefore, test problem 4A was considered. In this variant, compared to test problem 4, the well productivity index was increased to 1.0·10–10 m3; the thermal conductivity of the enclosing rock formations was reduced to 0.1 W/m·°C.

Figure 7 shows the simulation results with the initial parameters: changes in flow rate and wellhead temperature; solid‑phase saturation and CaCl2 concentration in the wellhead section over a 37-day production period. As in the previous test problems, the dynamics of wellbore filling with solid precipitate at various time points (t = 1 h, 1, 3, 5, 10, and 37 days) reveals non-uniform deposition, predominantly in the upper near-wellhead section. After just one week of operation, the upper part of the well is 50 % clogged, and the flow rate decreases from 14 to 5.5 kg/s. The total salt production is estimated at 3681 t. When converted to lithium, this amounts to 4.2 t, assuming a lithium mass fraction of 0.114 % in the initial brine mineralization.

Discussion

The brines are dominated by calcium, magnesium, potassium, and sodium chlorides. While sodium and potassium chlorides exhibit a weak temperature dependence of solubility, the solubility of calcium and magnesium chlorides – which crystallize as hydrates with a variable number of water molecules – clearly depends on temperature. Due to the strong temperature dependence of solubility, saturated concentrated solutions of calcium and magnesium chlorides are highly sensitive to fluctuations in external parameters. Even a slight decrease in temperature can trigger an avalanche‑like crystallization of hydrated chlorides from the brine. Calcium chloride dominates the composition of the brine produced from the well at the Kovykta gas condensate field (“Lithium” site), where geological exploration is underway and a pilot plant for the extraction of lithium‑bearing brines is being constructed. The brine must remain liquid at temperatures above 40-55 °C, when in the MgCl2–CaCl2–H2O subsystem a wide region is occupied by the crystallization of tachhydrite, and the figurative point of the brine lies close to the boundary of its precipitation.

Figure 2 shows the CS temperature profile, revealing that over most of the string’s length the temperature is below 35 °C, which in principle may lead to clogging at any section. The situation is especially critical in the first kilometre from the surface, where the temperature drops to 2-9 °C. This is the zone of avalanche‑like precipitation of antarcticite and bischofite. At depths of 600-1200 m, the well temperature ranges from 10 to 20 °C. Here, antarcticite will crystallize, and its amount may become significant enough to cause CS clogging. At depths of 1200-1900 m, where the CS temperature is 20-30 °C, the amount of precipitated antarcticite decreases, and tachhydrite begins to form instead. Below 1900 m (temperatures above 30 °C), tachhydrite may precipitate, and the amount of crystalline phases decreases with increasing temperature. Above 40 °C, the amount of precipitated tachhydrite decreases due to increased solubility, and the quantity of precipitated salt may no longer be critical for well operation, for example, due to mechanical removal of crystals by the pressurized brine flow.

It should be noted that during the extraction of hard-to-recover hydromineral raw materials at the “Lithium” site, it will be optimal to implement technical and technology solutions to maintain a high temperature (conventionally above 40-55 °C) in the casing string, production line, and wellhead equipment. Under high‑temperature conditions, antarcticite becomes unstable, and the tachhydrite crystallization field shrinks. As a result, the amount of precipitated salt may be small and insufficient to fill the internal space of the production line.

An alternative approach to addressing wellbore clogging by chloride salts is offered by Russian experience in optimizing production well performance [40]. Research was focused on the issue of reservoir permeability reduction due to wellbore colmation during the initial penetration in hydrocarbon production [41]. Simulation of rock fragmentation and process fluid flow was carried out [42], demonstrating that precipitate formation can be offset by its transport to the surface. The negative consequences of productive formation permeability decline are discussed in [43]. One countermeasure involves the use of process fluids that reduce surface tension. Technology for drilling through ice masses using the melting method was developed [44], highlighting both the relevance and technical feasibility of temperature control during well drilling operations. It should be noted that methods for extracting saturated brines prone to crystallization (hard‑to‑recover reserves) are described in several patents [31]. These propose a combination of solutions: a new wellhead design and piping configuration and drilling technology with simultaneous return and back‑injection into an absorbing horizon; during drilling pause – injection of low‑mineralized, stabilized brines into the bottomhole formation zone, followed by pressure release and transition to self‑flow mode with drill string heating. Additionally, there is a Russian patent for an invention describing a method for penetrating interlayers with abnormally high reservoir pressure and low permeability and porosity.

A technology of the thermocase was developed [45, 46] – namely, the creation of a thermal insulation layer in the CS [47] or of a hot heat‑transfer fluid flow. Initially, the thermocase technology was designed for oil production in permafrost regions, aimed at preventing permafrost thawing [48]. Materials such as basalt fibre, polyurethane foam, and others can be used as thermal insulators. It is possible that the thermocase technology may prove useful not only for preventing permafrost thawing, but also for controlling the temperature regime of wells during hydrodynamic studies and the extraction of hard-to-recover highly mineralized brines.

The technology of heating the production line with a hot heat‑transfer fluid flow can be considered optimal. This method was tested under actual production cycle conditions at the controlled overflow well 3A Znamenskaya and demonstrated its effectiveness. Therefore, to address the problem of wellbore clogging by salt precipitation from brine, the following existing technologies can be applied: heating with injection of low‑mineralized or essentially “pure” hot process water; well equipment heating; thermal insulation of well equipment.

TOUGH2‑EWASG simulation reproduces dynamic processes during the exploitation of sodium chloride brines and allows assessing the feasibility of operating under similar conditions with more soluble calcium chloride brines. In the model, salt crystallization occurs due to the reduced solubility of halite in response to temperature changes. However, the temperature dependence of NaCl solubility is relatively weak – in contrast to the solubility of calcium and magnesium chlorides. When extrapolating the simulation results to calcium and magnesium chloride solutions, a faster clogging of the wellbore space is observed compared to potassium chloride. The extraction method involving cyclic injection of hot water and pumping out the resulting brine (test problem 1) prevents wellbore clogging and ensures sustainable production of hydro‑mineral resources. However, this approach requires effective mixing of the injected hot water with the native brine. This can be easily simulated by increasing the hydrodynamic dispersion coefficient, however, achieving such mixing in practice may be challenging.

Thermohydrodynamic simulation (test problems 3 and 4A) of free‑flow operation, accounting for non‑steady heat transfer, demonstrated the feasibility of extracting saturated sodium chloride (27,387.7 t) and calcium chloride (3681 t) brines from the target productive reservoir – despite thermodynamic crystallization predicted by the well’s temperature profile. Lithium production is estimated at 31.2 t to 4.2 t per well. The thermohydrodynamic simulations reveal that the flow rate of free‑flowing wells declines in synchrony with decreasing temperature and increasing rate of wellbore filling with solid precipitate. The model reproduces field‑observed phenomena: rapid clogging of the production line, production decline within weeks (for calcium chloride saturated brines) or months (for sodium chloride saturated brines).

Conclusion

The KCl–MgCl2–CaCl2–H2O system contains about twenty phases, including ice and solution. When the CS clogs, two of them become important – antarcticite CaCl2‧6H2O and tachhydrite Mg2CaCl6·12H2O. Calcium and magnesium chloride salts crystallize from the brine mainly as crystalline hydrates with a variable number of water molecules. Their solubility increases significantly with rising temperature. The brine composition is dominated by calcium chloride – 442 g/l, magnesium chloride – 112 g/l, potassium chloride – about 5 g/l. During wellbore clogging, the behaviour of calcium and magnesium chlorides is critical because they are the dominant salts. Potassium-based salts, even if they precipitate, do so in small amounts. This suggests their role in clogging the production line and CS is insignificant and can be neglected.

In the temperature range from –35 to –10 °C – typical for Siberian winters – ice, magnesium and calcium chloride hydrates, and magnesium chloride dodecahydrate MgCl2·12H2O crystallize from the brine at the surface. Rubidium can enter this compound as an isomorphic impurity. Lithium, in turn, most likely remains in the liquid phase. At temperatures from –10 to 20 °C, antarcticite CaCl2‧6H2O can crystallize in an avalanche‑like manner, leading to wellbore clogging with salt deposits. As temperature rises, the two-phase equilibrium field of antarcticite with its saturated solution shrinks due to the expanding liquid field. This corresponds to an increase in antarcticite solubility and a decrease in the amount of precipitated salt. In the 20-30 °C temperature range, the antarcticite crystallization field continues to shrink, yet antarcticite still precipitates. At the same time, a narrow equilibrium field between the saturated solution and tachhydrite appears on the phase diagram. Tachhydrite can also crystallize in significant amounts both in the CS and near the wellhead. This temperature range is not ideal for operation. However, within these limits, antarcticite solubility is already relatively high, and the tachhydrite crystallization field is rather narrow. As a result, the amount of salt precipitated is likely to be lower than under colder conditions.

As the temperature rises further, within the 30-40 °C range, antarcticite is replaced by tachhydrite (a double salt with the formula Mg2CaCl6·12H2O). Additionally, carnallite KMgCl3·6H2O may precipitate from the brine, though only in small amounts. In this temperature range, wellbore clogging occurs not due to antarcticite but rather due to tachhydrite deposition. Increasing temperature leads to a shrinkage of the double hydrate crystallization field. In the 40-55 °C range, the figurative point of the brine approaches the two‑phase equilibrium line for tachhydrite crystallization. Consequently, although tachhydrite still crystallizes, the amount of salt formed relative to the brine mass is small. At higher temperatures to 100 °C, tachhydrite precipitates only in negligible quantities.

The well thermogram shows that down to a depth of 1200 m, the temperature is below 20 °C, and the CS may become clogged with antarcticite and bischofite. Below 1200 m, at temperatures above 20 °C, antarcticite is replaced by tachhydrite. Tachhydrite is also highly soluble, and at temperatures above 30 °C it will dominate the composition of the precipitated solid phase. However, as temperature increases, the amount of precipitated antarcticite decreases due to its rising solubility.

Summarizing the thermodynamic analysis, we can conclude that the optimal temperature conditions for operating deep wells to extract hard-to-recover highly concentrated calcium chloride brines are temperatures above 30-55 °C. Field experience with problematic wells shows that washing the CS with low‑mineralized solutions, well thermal insulation, and well heating techniques can be adapted for extracting hard-to-recover saturated and highly concentrated lithium‑bearing brines. The technical conditions required to maintain the necessary temperature ranges can be similar to the thermocase method. This method is currently used in developing hard-to-recover hydrocarbon resources in permafrost areas. Its purpose is twofold: to prevent permafrost thawing and to avoid deposition of heavy paraffins inside casing pipes.

Thermohydrodynamic simulation of a single free‑flowing well, under hydrogeological conditions similar to those of the Kovykta area in the south of the Siberian Platform, demonstrated the fundamental feasibility of long‑term operation (from one month to one year) with saturated sodium chloride and calcium chloride lithium‑bearing brines. Lithium production is estimated at 31.2 to 4.2 t per well.

Future research tasks include refining the fluid state module of TOUGH2‑EWASG for calcium chloride and magnesium chloride brines, validating the models using data from field tests at exploration and production sites of saturated lithium‑bearing chloride brines, developing methods for solving inverse problems to determine reservoir porosity and permeability, thermophysical properties and boundary conditions of target reservoirs, justifying technologies for sustainable well operation in the following modes: self‑overflow/free flow, pumping, combined self‑overflow with injection of hot water or steam.

1. Handbook of solubility. In 7 vol. Vol. 3: Ternary and multicomponent systems formed by inorganic substances. Book 3 / Comp. V.B.Kogan, S.K.Ogorodnikov, V.V.Kafarov. Leningrad: Nauka, 1970, p. 1221.

2. Kirgintsev A.N., Trushnikova L.N., Lavrentieva V.G. Solubility of inorganic substances in water. Leningrad: Khimiya, 1972, p. 248.

References

- Yurchik I.I. Lithium in brines of the Siberian salt basin. 20th International Scientific Congress Interexpo GEO-Siberia: Materialy Mezhdunarodnoi nauchnoi konferentsii “Nedropolzovanie. Gornoe delo. Napravleniya i tekhnologii poiska, razvedki i razrabotki mestorozhdenii poleznykh iskopaemykh. Ekonomika. Geoekologiya”, 15-17 maya 2024, Novosibirsk, Rossiya. Novosibirsk: Sibirskii gosudarstvennyi universitet geosistem i tekhnologii, 2024. Vol. 2. N 1, p. 247-250 (in Russian). DOI: 10.33764/2618-981X-2024-2-1-247-250

- Mohunov V.Yu., Gulyi N.I. Analysis of trends in modern technologies for the extraction of lithium from hydromineral raw materials. Nedropolzovanie XXI vek. 2022. N 4 (96), p. 38-50 (in Russian).

- Patrikeev P.A., Akhiyarov A.V., Kirsanov A.M. et al. Forecast of oil and gas potential within the Kochechumsko-Markhinskaya petroleum promising zone of the Lena-Tunguska petroleum province, taking into account the complex geological section saturated with products of intrusive trap magmatism. Fiziko-tekhnicheskie problemy dobychi, transporta i pererabotki organicheskogo syrya v usloviyakh kholodnogo klimata: Sbornik trudov III Vserossiiskoi konferentsii, posvyashchennoi 25-letiyu Instituta problem nefti i gaza SO RAN, 10-13 sentyabrya 2024, Yakutsk, Rossiya. Kirov: Mezhregionalnyi tsentr innovatsionnykh tekhnologii v obrazovanii, 2024, p. 75-80 (in Russian). DOI: 10.24412/cl-37255-2024-1-75-80

- Donskaya T.V., Gladkochub D.P. Post-collisional magmatism of 1.88-1.84 Ga in the southern Siberian Craton: An overview. Precambrian Research. 2021. Vol. 367. N 106447. DOI: 10.1016/j.precamres.2021.106447

- Chang S.A., Balouch A., Abdullah. Analytical perspective of lithium extraction from brine waste: Analysis and current progress. Microchemical Journal. 2024. Vol. 200. N 110291. DOI: 10.1016/j.microc.2024.110291

- Popov G.V., Pashkevich R.I. Kinetics of ion exchange of lithium from solutions in static conditions. Bashkir Chemical Journal. 2018. Vol. 25. N 4, p. 46-49 (in Russian). DOI: 10.17122/bcj-2018-4-46-49

- Belova T.P., Ratchina T.I. Research of lithium sorption by KU-2-8 cation exchanger from model solutions simulating geothermal fluids in the dynamic mode. Journal of Mining Institute. 2020. Vol. 242, p. 197-201. DOI: 10.31897/PMI.2020.2.197

- Mends E.A., Chu P. Lithium extraction from unconventional aqueous resources – A review on recent technological development for seawater and geothermal brines. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering. 2023. Vol. 11. Iss. 5. N 110710. DOI: 10.1016/j.jece.2023.110710

- Suharyanto A., Rohmah M., Lalasari L.H., Mubarok M.Z. Lithium adsorption behaviour from Ciseeng geothermal brine water onto Amberlite resin. AIP Conference Proceedings. 2024. Vol. 3003. Iss. 1. N 020113. DOI: 10.1063/5.0186324

- Ryabtsev A.D., Kotsupalo N.P., Menzheres L.T. et al. Implementation of an Integrated Technology for Processing Brines of the Calcium Chloride Type to Obtain a Bromineless Lithium Concentrate. Theoretical Foundations of Chemical Engineering. 2023. Vol. 24. N 9, p. 337-342. DOI: 10.1134/S0040579524700635

- Kotsupalo N.P., Nemudry A.P. Development of Processing Technology for Mining and Hydromineral Lithium-Containing Raw Materials. Scientific Basis for the Production of Selective Lithium Sorbent. Chemistry for Sustainable Development. 2021. Vol. 29. N 3, p. 346-353. DOI: 10.15372/KhUR2021312

- Bofill L., Bozetti G., Schäfer G. et al. Quantitative facies analysis of a fluvio-aeolian system: Lower Triassic Buntsandstein Group, eastern France. Sedimentary Geology. 2024. Vol. 465. N 106634. DOI: 10.1016/j.sedgeo.2024.106634

- Ashadi A.L., Martinez Y., Kirmizakis P. et al. First High-Power CSEM Field Test in Saudi Arabia. Minerals. 2022. Vol. 12. Iss. 10. N 1236. DOI: 10.3390/min12101236

- Herrmann L., Ehrenberg H., Graczyk-Zajac M. et al. Lithium recovery from geothermal brine – an investigation into the desorption of lithium ions using manganese oxide adsorbents. Energy Advances. 2022. Vol. 1. Iss. 11, p. 877-885. DOI: 10.1039/d2ya00099g

- Glen J.M.G., Earney T.E. New high resolution airborne geophysical surveys in Nevada and California for geothermal and mineral resource studies. Geothermal Resources Council Transactions. 2023. Vol. 47, p. 1738-1762.

- Kuzmenko P.S., Mikheeva E.D. Mineral resource base of deposits of lithium-bearing clays and tuffs. Nedropolzovanie XXI vek. 2024. N 2 (103), p. 14-19 (in Russian).

- Antipin V.S., Kuzmin M.I., Odgerel D. et al. Rare-Metal Li–F Granites in the Late Paleozoic, Early Mesozoic, and Late Mesozoic Magmatic Areas of Central Asia. Russian Geology and Geophysics. 2022. Vol. 63. N 7, p. 772-788.DOI: 10.2113/RGG20214409

- Alekseev V.I. Tectonic and magmatic factors of Li-F granites localization of the East of Russia. Journal of Mining Institute. 2021. Vol. 248, p. 173-179. DOI: 10.31897/PMI.2021.2.1

- Alekseev V.I. Type intrusive series of the Far East belt of lithium-fluoric granites and its ore content. Journal of Mining Institute. 2022. Vol. 255, p. 377-392. DOI: 10.31897/PMI.2022.21

- Alam M.A., Muñoz A. A critical evaluation of the role of a geothermal system in lithium enrichment of brines in the salt flats: A case study from Laguna Verde in the Atacama Region of Chile. Geothermics. 2024. Vol. 119. N 102970. DOI: 10.1016/j.geothermics.2024.102970

- Sudarikov C.M., Zmievskii M.V. Geochemistry of ore-forming hydrothermal fluids of the World ocean. Journal of Mining Institute. 2015. Vol. 215. p. 5-15 (in Russian).

- Fei Xue, Hongbing Tan, Xiying Zhang et al. Contrasting sources and enrichment mechanisms in lithium-rich salt lakes: A Li-H-O isotopic and geochemical study from northern Tibetan Plateau. Geoscience Frontiers. 2024. Vol. 15. Iss. 2. N 101768. DOI: 10.1016/j.gsf.2023.101768

- Zheng Hao, Zhao HaiXiang, Tan HongBing. Calculation of ore-forming material balance and material source of Li-B rich brines in Mami Co Lake, Tibet. Mineral Deposits. 2023. Vol. 42. N 2, p. 411-424. DOI: 10.16111/j.0258-7106.2023.02.011

- Kiryukhin A.V., Nazhalova I.N., Zhuravlev N.B. Hot water-methane reservoirs at southwest foothills of Koryaksky volcano, Kamchatka. Geothermics. 2022. Vol. 106. N 102552. DOI: 10.1016/j.geothermics.2022.102552

- Dugamin E.J.M., Cathelineau M., Boiron M.C. et al. Lithium enrichment processes in sedimentary formation waters. Chemical Geology. 2023. Vol. 635. N 121626. DOI: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2023.121626

- Al-Jawad J., Ford J., Petavratzi E., Hughes A. Understanding the spatial variation in lithium concentration of high Andean Salars using diagnostic factors. Science of the Total Environment. 2024. Vol. 906. N 167647. DOI: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.167647

- Baines A., Broadley M., Gines J. et al. Bare-earth satellite imagery and the search for hidden lithium-rich brines: An example from the Lithium Triangle in South America. The International Meeting for Applied Geoscience and Energy: Expanded Abstracts 2023 Technical Program, 28 August – 1 September 2023, Houston, TX, USA. Society of Exploration Geophysicists, 2023, p. 1136-1140. DOI: 10.1190/image2023-3909965.1

- Lattus J.M., Barber M.E., Skoković D. et al. Spaceborne Radars for Mapping Surface and Subsurface Salt Pan Configuration: A Case Study of the Pozuelos Salt Flat in Northern Argentina. Remote Sensing. 2024. Vol. 16. Iss. 8. N 1411. DOI: 10.3390/rs16081411

- Jiang Guo, Zhou Kefa, Wang Jinlin et al. Identification of lithium-beryllium granitic pegmatites based on deep learning. Earth Science Frontiers. 2023. Vol. 30. N 5, p. 185-186. DOI: 10.13745/j.esf.sf.2023.5.20

- Rossi C., Bateson L., Bayaraa M. et al. Framework for Remote Sensing and Modelling of Lithium-Brine Deposit Formation. Remote Sensing. 2022. Vol. 14. Iss. 6. N 1383. DOI: 10.3390/rs14061383

- Agafonov Yu.A., Alekseev S.V., Alekseeva L.P. et al. Manifestations of lithium brine and gas and abnormally high reservoir pressures in the south of the Siberian platform (fluid-geodynamic interpretation of geological, geophysical and geofield data; forecast of mining and geological conditions, innovative approaches and solutions in drilling and development of Kovykta Gas Condensate Field). In 2 vol. Vol. 1. Obzor problemy bureniya skvazhin v usloviyakh AVPD i vysokodebitnykh fontannykh pritokov redkometalnykh rassolov. Geologo-strukturnaya pozitsiya i stroenie Kovyktinskogo GKM. Gidrogeologiya i minerageniya kontsentrirovannykh rassolov. Stroenie mezhsolevykh prirodnykh rezervuarov osadochnogo chekhla galogenno-karbonatnogo kembriya. Polikomponentnye promyshlennye rassoly glubokikh gorizontov chekhla kak kompleksnoe gidromineralnoe syre. Tekhnologii pererabotki rassolov. Irkutsk: Irkutskii natsionalnyi issledovatelskii tekhnicheskii universitet, 2022, p. 302 (in Russian).

- Melentiev G.B., Shevchuk R.M., Delitsyn L.M. et al. Priority mineral resources and “critical” materials of Russia for production of lithium-ion batteries. Proceedings of the Komi Science Center of the Ural Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences. “Economic Sciences” series. 2023. N 3 (61), p. 59-70 (in Russian). DOI: 10.19110/1994-5655-2023-3-59-70

- Alexeev S.V., Alexeeva L.P., Vakhromeev A.G. Brines of the Siberian platform (Russia): Geochemistry and processing prospects. Applied Geochemistry. 2020. Vol. 117. N 104588. DOI: 10.1016/j.apgeochem.2020.104588

- Syrkov A.G., Prokopchuk N.R., Vorobiev A.G., Brichkin V.N. Academician N.S.Kurnakov as the founder of physico-chemical analysis – the scientific base for the development of new metal alloys and materials. Tsvetnye metally. 2021. N 1, p. 77-83 (in Russian). DOI: 10.17580/tsm.2021.01.09

- Soliev L., Jumaev M.T. Divarent equilibriumin multi-component systems. Chemical Journal of Kazakhstan. 2021. N 4 (76), p. 59-71 (in Russian). DOI: 10.51580/2021-1/2710-1185.49

- Khamrakulov Z.A., Askarova M.K., Tukhtaev S. Solubility of components in the systems MgCl2–CaCl2–H2O and (48.2% CaCl2 + 51.8% MgCl2)–NaClO3–H2O. Russian Journal of Inorganic Chemistry. 2015. Vol. 60. N 10, p. 1286-1291. DOI: 10.1134/S0036023615080100

- Vakhromeev A.G., Smirnov A.S., Sverkunov S.A. et al. Technological variants of developing lithium-bearing deposits of hard-of-recover inter-salt brine-bearing formations by high-pressure fluid system. Construction of oil and gas wells on land and sea. 2025. N 6 (390), p. 5-13 (in Russian).

- Feng Liu, Gui-ling Wang, Wei Zhang et al. Using TOUGH2 numerical simulation to analyse the geothermal formation in Guide basin, China. Journal of Groundwater Science and Engineering. 2020. Vol. 8. N 4, p. 328-337. DOI: 10.19637/j.cnki.2305-7068.2020.04.003

- Pruess K., Oldenburg C., Moridis G. TOUGH2 User’s Guide, Version 2.0. Ernest Orlando Lawrence Berkley National Laboratory, 1999. Report N LBNL-43134, p. 204. DOI: 10.2172/751729

- Toporkova E.V., Konkin V.V., Lashkin N.E., Zaitsev K.A. Improving the technology of oil treatment at a fault-line oil field. Akademicheskii zhurnal Zapadnoi Sibiri. 2015. Vol. 11. N 5 (60), p. 35-36 (in Russian).

- Gasumov R.A. Causes of Fluid Entry Absence When Developing Wells of Small Deposits (on the example of Khadum-Batalpashinsky horizon). Journal of Mining Institute. 2018. Vol. 234, p. 630-636. DOI: 10.31897/PMI.2018.6.630

- Grigoriev B.S., Eliseev A.A., Pogarskaya T.A., Toropov E.E. Mathematical Modeling of Rock Crushing and Multiphase Flow of Drilling Fluid in Well Drilling. Journal of Mining Institute. 2019. Vol. 235, p. 16-23. DOI: 10.31897/PMI.2019.1.16

- Rogov E.A. Study of the well near-bottomhole zone permeability during treatment by process fluids. Journal of Mining Institute. 2020. Vol. 242, p. 169-173. DOI: 10.31897/PMI.2020.2.169

- Serbin D.V., Dmitriev A.N. Experimental research on the thermal method of drilling by melting the well in ice mass with simultaneous controlled expansion of its diameter. Journal of Mining Institute. 2022. Vol. 257, p. 833-842. DOI: 10.31897/PMI.2022.82

- Artemenkov V.Y., Erehinskiy B.A., Zariaev I.A. Application of insulated lift pipes for oil and gas extraction. Pipeline transport: Theory and practice. 2017. N 2 (60), p. 20-23 (in Russian).

- Grishin M.S., Galeev A.R. Study of a combined technology for wellbore isolation in permafrost intervals. Problemy razrabotki mestorozhdenii uglevodorodnykh i rudnykh poleznykh iskopaemykh. 2023. Vol. 1, p. 154-159 (in Russian).

- Poskonina E.A., Kurchatova A.N. Determination of the minimal thermocase length depending on well spacing. PROneft. Professionals about Oil. 2022. N 2 (12), p. 66-70 (in Russian). DOI: 10.24887/2587-7399-2019-2-66-70

- Badanina Yu.V., Komkov M.A., Bochkarev S.V., Pavlovskaya K.V. Establishment of tubing with high-performance composite thermal barrier coating for steam-heat processing wells. Fundamental Research. 2016. N 11, p. 461-466 (in Russian).