Study of the interaction between the drilling fluid and lake water during the opening of the subglacial Lake Vostok in Antarctica

- 1 — Ph.D. Assistant Lecturer Empress Catherine II Saint Petersburg Mining University ▪ Orcid

- 2 — Ph.D. Scientific Supervisor of Laboratory Empress Catherine II Saint Petersburg Mining University ▪ Orcid ▪ Scopus

- 3 — Postgraduate Student Empress Catherine II Saint Petersburg Mining University ▪ Orcid ▪ Scopus

- 4 — Ph.D. Assistant Lecturer Empress Catherine II Saint Petersburg Mining University ▪ Orcid ▪ Scopus

- 5 — Ph.D. Associate Professor Empress Catherine II Saint Petersburg Mining University ▪ Orcid ▪ Scopus

Abstract

The article presents the laboratory results of formation and breaking of water and organosilicon fluid emulsions, as well as formation and dissociation of nitrogen hydrates under PT conditions close to the conditions at the interface of a glacier and subglacial Lake Vostok using the Gas Hydrate Autoclaves GHA 350 complex. The studied organosilicon fluid was polydimethylsiloxane WACKER AK-10 (in the Russian classification according to GOST 13032-77, PMS-10) with a density of 0.9359 g/cm3 and a kinetic viscosity of 10 mm2/s. We found that a decrease in the emulsion temperature leads to an increase in the time of its breaking, the formation of microemulsions and multiple emulsions of the “oil – in water – in oil” type. This is especially evident at temperatures ≤10 °C. The average emulsion breaking time was 107 s. The minimum emulsion breaking time was observed at a minimum mixer rotation speed of 100 rpm and a maximum temperature of 60 °C, and the maximum emulsion breaking time was observed at a mixer rotation speed of 500 rpm and a temperature of –2.8 °C. We found that nitrogen hydrates were formed at a pressure of 35.0±0.5 MPa and a temperature of ≤ –1 °C.

Funding

Research is executed within the State task N FSRW-2024-0003.

Introduction

In 1996, Russian scientist A.P.Kapitsa [1] published the first official paper about the discovery of a huge lake below a thick Antarctic glacier in the Vostok Station area. In this regard, the scientific research shifted towards a comprehensive interdisciplinary and international study of subglacial lakes [2, 3]. To date, 675 subglacial lakes have been discovered in Antarctica [4], and only four ice drilling projects with subsequent penetration into the lakes have been implemented: Vostok [5, 6], Whillans [7, 8], Mercer [8, 9], and Filchner [10]. The largest of the discovered lakes, Lake Vostok [2, 11, 12], is of greatest interest to the Russian scientific community. Since 1990, experts from the Mining University and the Arctic and Antarctic Research Institute (AARI) with the technology and scientific support from French experts and the logistical support from American experts drilled the deep 5G borehole.

The purpose of drilling a deep borehole was initially to collect a core sample through the entire glacier thickness, but the discovery of the subglacial lake added another goal – environmentally friendly opening of the lake with subsequent clean sampling of lake water [13, 14]. As a result of long-term drilling, on 5 February 2012, at a depth of 3769.3 m, Russian scientists reached the surface of the subglacial Lake Vostok, and on 25 January 2015, they opened it again [5, 6, 13]. However, they did not succeed to collect clean lake water samples. Currently, experts from the Mining University are actively developing effective and environmentally friendly technologies for drilling the ice cover and studying subglacial environments [15-19].

Deep ice drilling requires various low-temperature fluids (drilling fluids – DF), which are poured into the well from the wellhead. DF provide compensation for lithostatic (overburden) pressure and are a cleaning agent. Without them, deep ice drilling is impossible, since ice is a plastic-brittle rock, in which plastic deformations are especially active at high pressures and massif temperatures close to melting. As a result, well diameter decreases, which leads to complications and accidents.

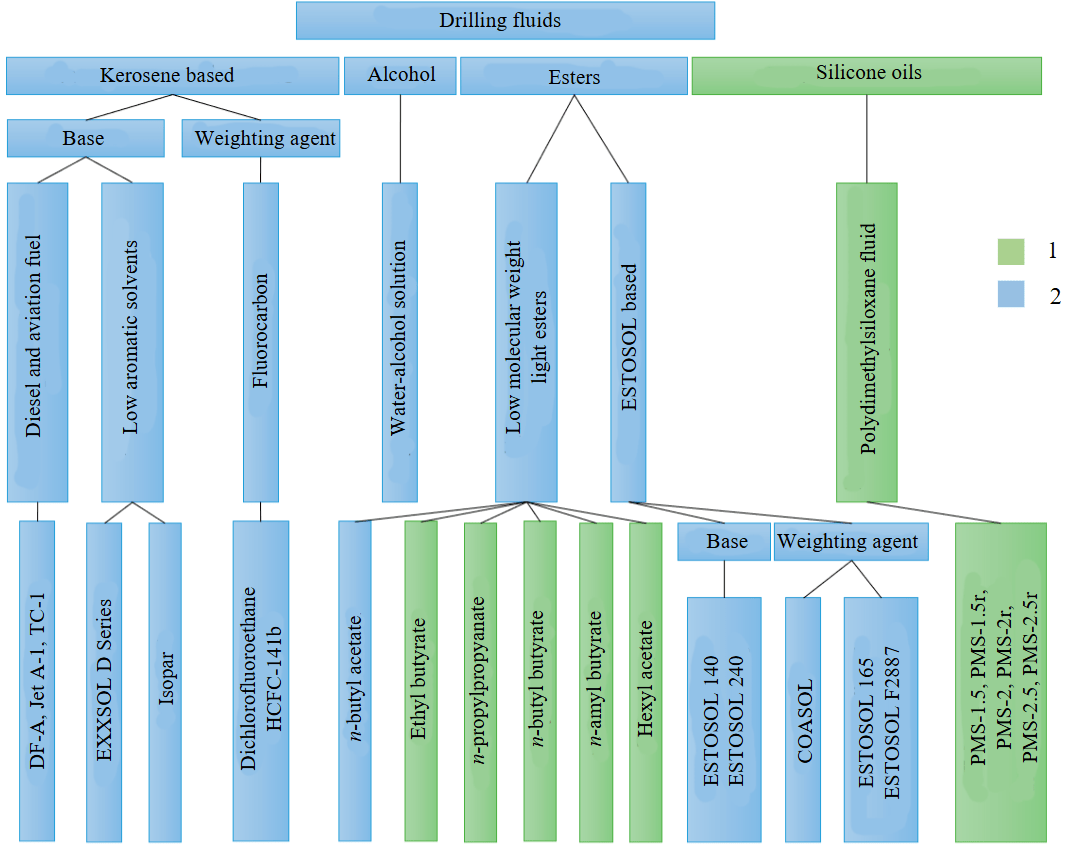

Low-temperature fluids can be divided into four main groups (Fig.1): two-component petroleum base fluids with added weighting agent, alcohol compounds, ester compounds, and silicone oils [20, 21]. Most of these fluids are environmentally unsafe. For example, the most common DF – a mixture of hydrocarbons used in the 5G well, despite its advantages (cheapness, low viscosity, density adjustable over a wide range, inertness with respect to ice, hydrophobicity), is based on aviation fuel (TS-1, Jet A-1) being a highly toxic compound, and the fluorocarbon weighting agents used (freon HCFC-141b) have a negative impact on the Earth’s ozone layer [22].

Opening of subglacial reservoirs is based on the pressure undercompensation, which is the difference between the lithostatic pressure Pg (ice pressure) and the hydrostatic pressure Pgdf (DF pressure). The lithostatic pressure must be greater than the hydrostatic pressure. Compliance with this condition ensures that water rises from the lake into the well during opening, and its flow continues until the moment when the pressure balance “fluid in the well – lake” is reached [23-25].

Fig.1. Classification of drilling fluids [20]

1 – used in drilling; 2 – promising

At the moment of opening, the stream of lake water entering the well actively mixes with the DF, forming an emulsion. Moreover, the higher the value of the differential pressure, the higher the initial speed of the stream, and, accordingly, the speed and height of the lake water rise into the well [25]. The emulsion is a mixture of water and colder DF, which can contribute to faster freezing, in comparison with clean water, and to the contamination of the lake water in the well, which will not allow collecting clean samples [26-28].

Opening can also be complicated by hydrates formation, which hinders the movement of equipment in the well and increases the risk of tool freezing. Formation waters containing gases of organic and inorganic origin, acting as hydrate formers, and come from the lake bottom surface. The growth of the hydrate phase occurs under certain PT conditions and the presence of hydrate-forming substances. This process is accelerated by high flow rates, mixing, crystallization centres, and free water. During the subglacial reservoir opening, active mixing occurs, which, given the large interface between lake water and cold DF, leads to solid hydrates formation [29-31].

Hydrate formation is caused by both the chemical interaction of water and DF, and the budget of atmospheric gases – oxygen and nitrogen, which enter the lake with melt water [32, 33]. For example, in 2012 and 2015, when the subglacial Lake Vostok was opened, a column of freon clathrates was formed, which separated the lake water and DF. The PT conditions at the “lake – glacier” interface are optimal for the formation of many types of hydrates. In [32] the volume and concentration of atmospheric gases entering the lake are indirectly estimated, but direct measurements were not made due to the lack of access to the subglacial space.

This article discusses the use of promising environmentally friendly DF – silicone (organosilicon) fluids (oils) [34]. Silicone fluids are transparent, colourless, odourless, practically insoluble in water and highly resistant to chemical and oxidative degradation [35]. They have a wide range of industrial, consumer, food, and pharmaceutical application both in pure form and as an ingredient in finished products. Silicone additives can often be found in cosmetics. Many suppliers use these silicone fluids to make their own industrial mixtures and emulsions, but silicone fluids are produced by only a few companies in the world and are a commercial product.

Silicone fluids are used in the food industry. For example, the food additive E900 is a liquid polydimethylsiloxane (PMS) and is an antifoam in the industrial production of food. The additive is used as a binding agent, stabilizer, texturizer, anti-caking and anti-clogging agent, which confirms its environmental safety [22, 36]. PMS is also used as an additive to drilling fluids when drilling production wells for oil and gas [21]. The development and investment in the production of organosilicon fluids is steadily increasing every year, which can ultimately lead to a rational distribution of their production considering consumption, logistics, and energy supply of processes, especially in fast-growing Asian regions, as well as the discovery of new areas of application (for example, in deep ice drilling in the Arctic and Antarctic [37, 38]).

The advantages of PMS include environmental friendliness, non-toxicity, hydrophobicity, miscibility, preservation of density and rheological properties in a wide range of temperatures. The disadvantages are high cost, low evaporation rate, high compressibility, and significant change in density depending on temperature.

A new technological solution for PMS is its use as a DF in deep ice drilling [20]. Experts from Russia, China, the USA, and Europe conduct comprehensive studies on the interaction of PMS with ice slurry, choosing brand and manufacturer for specific drilling conditions based on density and rheological properties, conduct experimental drilling, study the effect on the hydraulic system and interaction with materials, etc.

Currently, there are no implemented well drilling projects using PMS [21]. Therefore, ice drilling and opening of subglacial reservoirs using linear PMS remain poorly understood. Modelling and forecasting the subglacial reservoir opening while ensuring processing and environmental requirements needs a detailed consideration of formation and breaking of emulsions (water and PMS) and gas hydrates. The study target is the interaction between PMS and lake water during the subglacial reservoir opening, and the subject is the formation and breaking of emulsions and gas hydrates. The purpose of the study is to determine the influence of fluid temperature, the intensity of their mixing, and the type of gas on the formation and breaking of emulsions and gas hydrates, considering the PT conditions at the glacier and the subglacial Lake Vostok interface.

Research methods

The organosilicon fluid WACKER AK-10 (PMS-10 in the Russian classification according to GOST 13032-77) from the German chemical company Wacker Chemie AG was used as the test fluid (Table 1).

Table 1

Properties of organosilicon fluid WACKER AK-10 at T = 25 °C [9]

|

Parameter |

Indicator |

Determination method |

|

Visibility |

Colourless, pure |

– |

|

Density, g/cm3 |

0.93 |

DIN 51757 |

|

Boiling point, °C |

180 |

ISO 2592 |

|

Flash point (fluid), °C |

365 |

EN 14522 |

|

Pour point, °C |

–80 |

DIN 51794 |

|

Surface tension, N/m |

0.020 |

DIN 53914 |

|

Kinetic viscosity, mm2/s |

10 |

DIN 53019 |

|

Dynamic viscosity, MPa·s |

9.3 |

|

|

Coefficient of thermal expansion at 0-150 °C, m2·10–4/(m2 · °C) |

10 |

|

The studies were conducted using laboratory equipment of the Arctic Research Centre of the Mining University. At the initial stage, the density and rheological properties of the fluid under study were determined in laboratory conditions. The density of WACKER AK-10 was measured by two independent methods – by Mettler Toledo Density meter Easy D40 and an AON-1 hydrometer; temperature – using a digital thermometer LT-300; viscosity – by a Fann 35SA viscometer. The formation and breaking of emulsions and gas hydrates were studied using the German Gas Hydrate Autoclaves GHA 350 system, which includes a GHA-350 autoclave, an overhead mixer, a Huber Ministat 240 thermostat, gas boosters with a maximum pressure of 15 and 40 MPa, a model gas preparation system, three video cameras, and a computer. The gas hydrate autoclave system makes it possible to generate PT conditions close to the conditions at the point of opening of the subglacial Lake Vostok by borehole 5G (pressure 33.78±0.05 MPa, ice melting temperature at the glacier/lake interface –2.72±0.10 °C [8], volume of fluids in the autoclave – water 200 ml, PMS 125 (200) ml). Methylene blue dye concentrate was added to the water in advance for better visualization of the process. Nitrogen, helium, and their mixture in a 1:1 ratio were used as the gas to generate pressure. Lake water was obtained from a lake ice core from borehole 5G at Vostok Station. Laboratory studies were conducted with video recording of the emulsion formation and breaking at a pressure P = 35.0±0.2 MPa with a change in the mixer rotation speed n from 100 to 700 rpm and emulsion temperature Te from –3.5 to 60 °C. The fluid mixing time was 60 s (selected experimentally in such a way that the emulsion did not change its dispersion upon further mixing). Experiments under the same PTe conditions were conducted 1-4 times. Upon completion of the experiments, all video recordings were processed visually.

Discussion

Results of density and rheology measurements of WACKER AK-10 at T = 25 °C: density 0.9359 g/cm3, kinetic viscosity 10 mm2/s. Ten series (168 experiments, including seven experiments with video recording 20-600 min long) of laboratory studies of formation and breaking of emulsions were conducted.

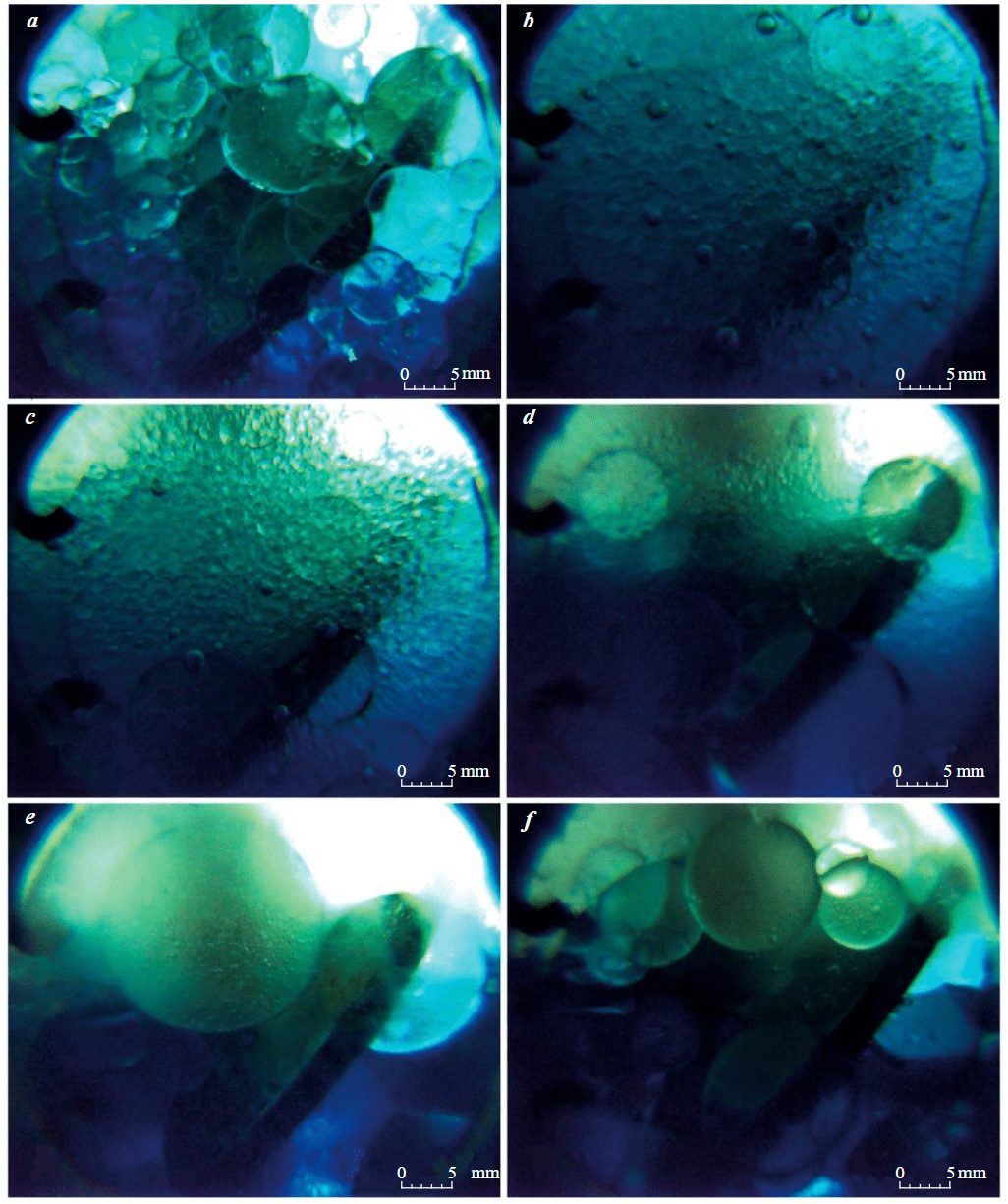

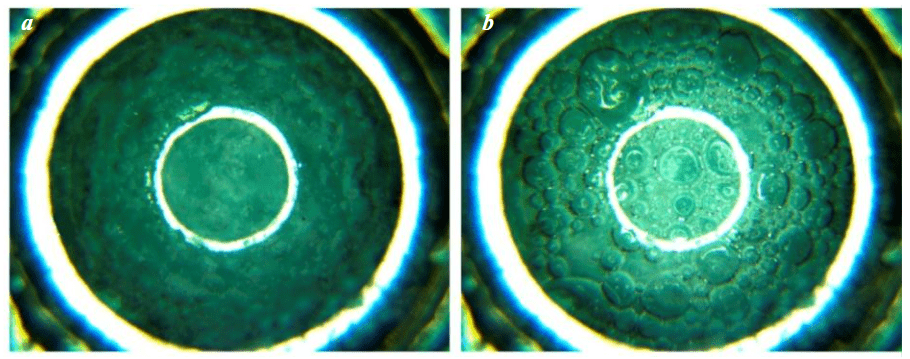

The intensity of mixing has a great influence on the dispersion of the emulsion. Mixing WACKER AK-10 and water at P = 35 MPa and rotation speed n < 200 rpm leads to the formation of polydisperse emulsions, and at rotation speed n ≥ 200-400 rpm (the range is determined by the change in Te) monodisperse emulsions are formed. Increasing the rotation speed of the mixer leads to a decrease in the size of the emulsion globules. Fig.2, a shows the emulsion at the moment of stopping the mixer, formed at Te = 0 °C, P = 35 MPa, and n = 100 rpm. It is polydisperse, since the globules have different sizes (0.2-6 mm). The emulsion in Fig.2, b formed at T = 0 °C, P = 35 MPa and n = 700 rpm is monodisperse, the size of its globules is 1-2 mm.

Lowering the temperature of the mixed fluids T ≤ 10 °C leads to the formation of finely dispersed emulsions with globule sizes of 0.1-0.5 mm (Fig.2, c, d). Lowering the temperature of the fluids to 0 °C and below in rare cases leads to the formation of multiple emulsions of the O/W/O (oil – in water – in oil) type. Fig.2, e, f show emulsions in which the diameter of a large water globule is 6.75 mm with small organosilicon fluid globules inside with a diameter of 0.05-0.30 mm. Usually, the lifetime of such individual globules does not exceed 5 min.

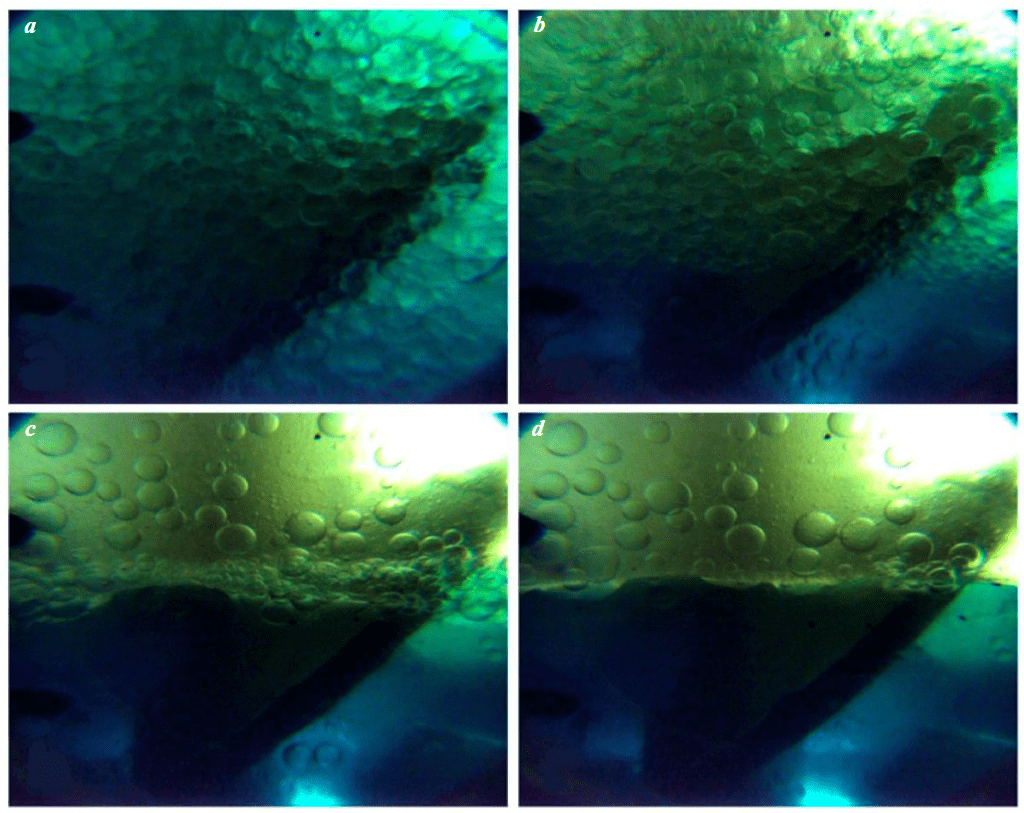

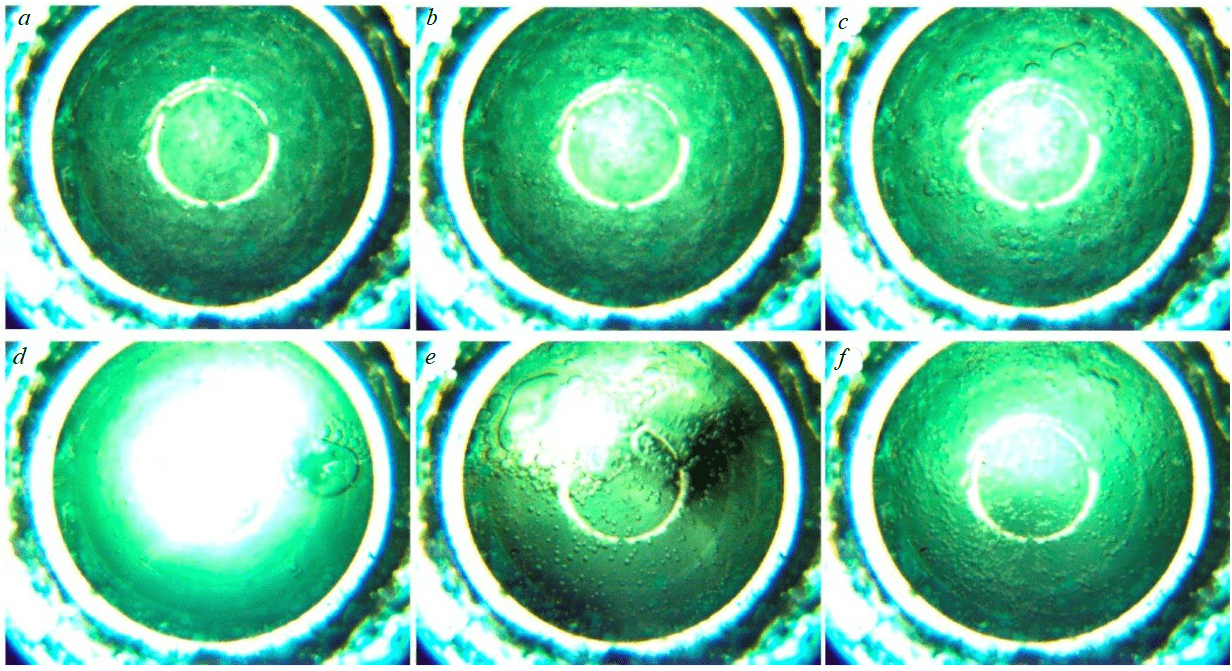

Emulsion breaking is shown in Fig.3. After stopping the mixing, active merging of water globules and the formation of larger ones, exceeding the initial size by 2-7 times, is observed, while kinetic instability appears, leading to creaming of emulsions (floating of the dispersed phase particles under the influence of gravity; in this case, the dispersed phase is water) with subsequent coalescence.

Fig.2. Results of formation and breaking of emulsions and water: a – type of emulsion at the moment of stopping the mixer at T = 0 °C and n = 100 rpm; b – type of emulsion at the moment of stopping the mixer at T = 0 °C and n = 700 rpm; c – formation of finely dispersed emulsions during breaking at T = 0 °C and n = 600 rpm; d – formation of finely dispersed emulsions during breaking at T = –3.5 °C and n = 400 rpm; e – formation of an O/W/O emulsion at T = –2.8 °C and n = 100 rpm; f – formation of an O/W/O emulsion at T = –3.5 °C and n = 150 rpm

Fig.3. Breaking of the WACKER AK-10 and water emulsion at P = 35 MPa, T = 10 °C, n = 250 rpm: a – 10 s; b – 30 s; c – 60 s; d – 84 s (complete breaking of the emulsion)

Video by link webm

Merging (coalescence) of two globules with formation of a new, larger globule is shown in Fig.4. When a clear interface between the emulsion and water appears in the video, a finely dispersed emulsion is formed on it. The layer of globules gradually decreases and eventually larger features are formed – floccules and globules – a set of several macromolecules. Floccules are broken in the first minutes, and the existence time of individual globules can reach tens of hours. The individual globules that survive the longest are those that are at the contact between two fluids and a solid surface, which leads to their subsequent fusion.

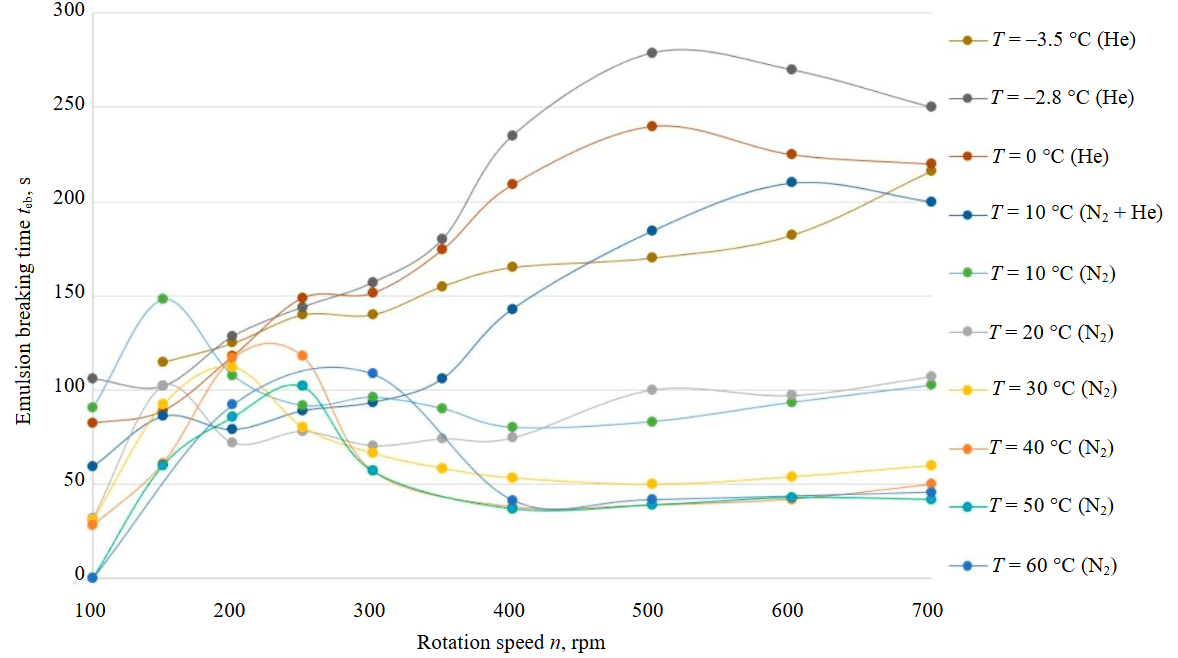

The laboratory results of the emulsion breaking time are presented in Table 2 and Fig.5. At a mixer rotation speed in the range of 150-300 rpm using nitrogen, the upper extrema of the emulsion breaking time are observed, which decrease to minimum values at n = 400 rpm. At n > 400 rpm, the dependence on the rotation speed decreases and becomes linear, this is especially evident at Te = 30-60 °C. A shift in the emulsion breaking time extrema is also observed depending on the mixer rotation speed, so at Te = 60 °C the extremum is reached at n = 300 rpm, and at Te = 10 °C the extremum is at n = 150 rpm. Figure 5 shows the dependences of the emulsion breaking time on the mixer rotation speed using helium. A linear, weakly ascending dependence is observed, and mathematical models are developed for these data in order to determine the emulsion breaking time y depending on the fluid temperature T and the mixer rotation speed x:

Fig.4. Coalescence of globules at T = 10 °C: a – two separate globules; b – fusion of globules; c – a single globule

These models are of the greatest interest, since their PT conditions are close to that of at the interface of the subglacial Lake Vostok and the glacier.

Table 2

Laboratory results of breaking of the WACKER AK-10 (PMS-10) and water emulsion

|

Item N |

Rotation speed n, rpm |

Gas used to generate pressure in the autoclave |

|||||||||

|

Nitrogen (N2) |

N2+He |

Helium (He) |

|||||||||

|

Volume of fluid in the autoclave |

|||||||||||

|

125 ml DF + 200 ml water |

200 ml DF + 200 ml water |

||||||||||

|

Average emulsion breaking time teb at different temperatures, s |

|||||||||||

|

60 °С |

50 °С |

40 °С |

30 °С |

20 °С |

10 °С |

10 °С |

0 °С |

–2,8 °С |

–3,5 °С |

||

|

1 |

100 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

28.0 |

31.0 |

32.0 |

90.5 |

59.3 |

82.5 |

106.0 |

– |

|

2 |

150 |

– |

60.0 |

61.0 |

92.0 |

102.0 |

148.3 |

86.0 |

89.0 |

102.0 |

115.0 |

|

3 |

200 |

92.0 |

85.7 |

117.0 |

112.0 |

72.0 |

107.8 |

79.0 |

118.0 |

128.5 |

125.0 |

|

4 |

250 |

– |

102.0 |

118.0 |

80.3 |

78.0 |

91.7 |

89.0 |

149.0 |

144.0 |

140.0 |

|

5 |

300 |

108.5 |

57.0 |

57.0 |

66.5 |

70.5 |

96.0 |

93.5 |

151.5 |

157.0 |

140.0 |

|

6 |

350 |

– |

– |

– |

58.5 |

74.0 |

90.0 |

106.0 |

174.5 |

180.0 |

155.0 |

|

7 |

400 |

41.5 |

37.0 |

38.0 |

53.5 |

74.5 |

80.0 |

143.0 |

209.0 |

235.0 |

165.0 |

|

8 |

500 |

41.8 |

39.0 |

39.0 |

50.0 |

100.0 |

83.0 |

184.5 |

240.0 |

279.0 |

170.0 |

|

9 |

600 |

– |

43.0 |

42.0 |

54.0 |

97.0 |

93.3 |

210.0 |

225.0 |

270.0 |

182.0 |

|

10 |

700 |

45.8 |

42.0 |

50.0 |

60.0 |

107.0 |

102.5 |

200.0 |

220.0 |

250.0 |

216.0 |

Changing the gas type and increasing the WACKER AK-10 sample volume from 125 to 200 ml leads to an increase in the emulsion breaking time. In the rotation speed range of 100-250 rpm, the minimum emulsion breaking time is observed when using helium, in the range of 250-300 rpm, the emulsion breaking time for helium and nitrogen is the same, and above 300 rpm, emulsions with helium are broken twice as slowly as emulsions using nitrogen.

Fig.5. Dependences of the WACKER AK-10 and water emulsion breaking time on the mixer rotation speed at T = –3.5-60.0 °C and P = 35 MPa

A decrease in the temperature of fluids leads to an increase in the emulsion breaking time, this is especially evident at a temperature of Te ≤ 20 °C and below. For example, a change in temperature from 30 to 10 °C with the same mixing speed n = 700 rpm increases the emulsion breaking time by two times.

The study of formation and breaking (dissociation) of hydrates in a mixture of water, organosilicon fluid, and gas under conditions close to the surface conditions of the subglacial Lake Vostok was conducted using a gas hydrate autoclave system. Considering the procedure of opening subglacial reservoirs and the PT conditions for hydrate formation, the required temperature range is from –10 to +10 °C. Based on the laboratory results, nitrogen hydrates are formed at P = 35±0.5 MPa and T ≤ –1 °C. This means that if there is a sufficient volume of nitrogen in the ice, nitrogen hydrates can form even before opening. Hydrates are also formed in a mixture of nitrogen and helium in a 1:1 ratio at P = 35±0.5 MPa and T ≤ –2.8 °C. Considering the inertness of helium, the compounds formed are nitrogen hydrates.

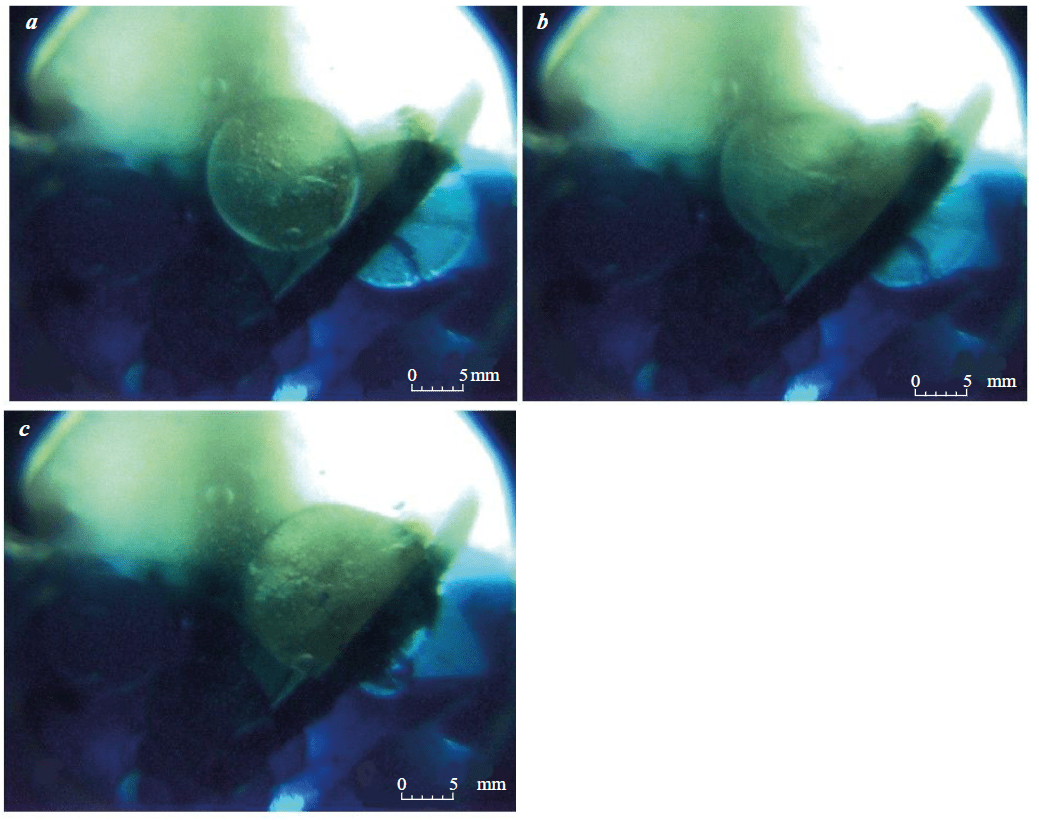

Addition of inert gas – helium – to nitrogen resulted in a shift in PT conditions for the formation of solid gas hydrates towards a temperature decrease. The use of helium to generate pressure in the autoclave and the presence of residual nitrogen in the fluids resulted in the formation of nitrogen hydrate at P = 35±0.5 MPa and T ≤ –5 °C (Fig.6, 7, a). In this case, the exact nitrogen content is difficult to determine. In some experiments, an increase in the mixer rotation speed resulted in its freezing in the autoclave, which caused the experiment termination. This occurred due to the instantaneous intensification of the formation of a large amount of hydrates due to the active mixing of water and organosilicon fluid. This phenomenon should be especially considered when developing ice drilling technologies and opening subglacial reservoirs.

It is known that dissociation of gas hydrates is initiated by decreasing pressure or increasing temperature. After decreasing the pressure in the autoclave from 35 to 25 MPa, small gas bubbles of 0.2-0.8 mm are released from the hydrates and accumulate in a closed space (Fig.7, b). The bubbles merge and form larger bubbles of 1-5 mm in size. Upon accumulation of a critical volume of gas (70-90 s after the start of the pressure change), the bubbles collapse and the gas escapes upward (Fig.7, c). The dissociation intensifies with the release of the first bubbles, and after 30-40 s, an increase in their size from 0.2-0.8 to 0.8-5 mm is observed (Fig.7, d). They cover more than 70 % of the viewing window surface. The merging of small bubbles into larger ones and their release continues for 40-60 s, after which the size of the resulting bubbles decreases again to 0.2-0.8 mm, and individual mergers into bubbles to 5 mm are formed (Fig.7, e, f).

Fig.6. Formation and breaking of nitrogen hydrate: a – before dissociation; b – after dissociation of nitrogen hydrates at T = –5 °C and P = 25 MPa

Fig.7. Dissociation of nitrogen hydrate at T = 0 °C and P = 25 MPa after the time: a – 0 min; b – 1 min; c – 2 min; d – 3 min; e – 4 min; f – 5 min

The decrease in temperature in the autoclave T ≤ 0 °C and the formation of ice/hydrates on the inside of the viewing windows for video cameras leads to condensation on the outside. This interferes with visual observation of the processes, which must be considered in further studies.

Summary

A set of investigations was conducted aimed at studying the formation and breaking of emulsions and gas hydrates during the interaction of two liquids (water and organosilicon fluid) and pressure generation using helium and/or nitrogen, which was a kind of test survey, since laboratory studies of emulsions and gas hydrates under PT conditions close to the conditions at the interface of the glacier and subglacial Lake Vostok were not conducted.

The influence of fluid temperature, mixing intensity, and gas type on the formation and breaking of emulsions from water and WACKER AK-10 was studied:

- low thermodynamic and kinetic stability of the studied emulsion is observed;

- the intensity of mixing largely influences the dispersion (with an increase in mixing intensity, the size of globules decreases) and the time of breaking of emulsions (experiments with nitrogen showed maximum points at a mixer rotation speed n = 150-300 rpm, with helium at a mixer rotation speed n = 600-700 rpm).

Conclusion

The approved laboratory research methodology using the Gas Hydrate Autoclaves GHA 350 is applicable for studying the formation and breaking of emulsions and gas hydrates. In laboratory conditions, using modern verified equipment, the density and rheological properties of the studied organosilicon fluid WACKER AK-10 were measured at T = 25 °C: density 0.9359 g/cm3, kinetic viscosity 10 mm2/s.

It was found that a decrease in the emulsion temperature leads to an increase in the time of its breaking, the formation of microemulsions, which are characterized by a decrease in the interfacial tension between the aqueous and organic phases to ultra-low values, and multiple emulsions of the O/W/O type. This is especially evident at Te ≤ 10 °C. The average emulsion breaking time was 107 s. The minimum emulsion breaking time is observed at a minimum mixer rotation speed n = 100 rpm and a maximum temperature Te = 60 °C, and the maximum emulsion breaking time is observed at a mixer rotation speed n = 500 rpm and a temperature Te = –2.8 °C.

It was found that nitrogen hydrates are formed at a pressure P = 35±0.5 MPa and a temperature T ≤ –1 °C. Addition of an inert gas – helium – to nitrogen leads to a shift in the PT conditions for the formation of nitrogen hydrates – with a gas ratio of 1:1, nitrogen hydrates are formed at P = 35±0.5 MPa and T ≤ –2.8 °C.

Research into the formation and breaking of emulsions and gas hydrates is relevant and significant in developing the technology of environmentally safe and accident-free opening of subglacial reservoirs using organosilicon fluids.

In further investigations, it is necessary to use other brands of organosilicon fluids, for example, PMS-1.5, PMS-2.0, PMS-2.5, PMS-3.0, PMS-1.5r, PMS-2.0r, PMS-2.5r, which are of greatest interest from the point of view of applicability in opening the subglacial Lake Vostok.

References

- Popov S.V., Masolov V.N., Lukin V.V. Russian geophysical research of the Subglacial Lake Vostok, East Antarctica. Problems of Geography. 2020. Vol. 150, p. 212-224 (in Russian).

- Siegert M.J. A 60-year international history of Antarctic subglacial lake exploration. Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 2018. Vol. 461, p. 7-21. DOI: 10.1144/SP461.5

- Bolshunov A.V., Vasiliev N.I., Timofeev I.P. et al. Potential technological solution for sampling the bottom sediments of the subglacial lake Vostok: relevance and formulation of investigation goals. Journal of Mining Institute. 2021. Vol. 252, p. 779-787. DOI: 10.31897/PMI.2021.6.1

- Livingstone S.J., Yan Li, Rutishauser A. et al. Subglacial lakes and their changing role in a warming climate. Nature Reviews Earth & Environment. 2022. Vol. 3. Iss. 2, p. 106-124. DOI: 10.1038/s43017-021-00246-9

- Тalalay P.G., Markov A.N. Thermobaric Conditions at Ice-Water Interface in Subglacial Lake Vostok, East Antarctica. Natural Resources. 2015. Vol. 6. N 6, p. 423-432. DOI: 10.4236/nr.2015.66040

- Litvinenko V.S. Unique engineering and technology for drilling boreholes in Antarctic ice. Journal of Mining Institute. 2014. Vol. 210, p. 5-10 (in Russian).

- Malczyk G., Gourmelen N., Werder M. et al. Constraints on subglacial melt fluxes from observations of active subglacial lake recharge. Journal of Glaciology. 2023. Vol. 69. Iss. 278, p. 1900-1914. DOI: 10.1017/jog.2023.70

- Mikucki J.A., Lee P.A., Ghosh D. et al. Subglacial Lake Whillans microbial biogeochemistry: a synthesis of current knowledge. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A. 2016. Vol. 374. Iss. 2059. N 20140290. DOI: 10.1098/rsta.2014.0290

- Yan Zhou, Xiangbin Cui, Zhenxue Dai et al. The Antarctic Subglacial Hydrological Environment and International Drilling Projects: A Review. Water. 2024. Vol. 16. Iss. 8. N 1111. DOI: 10.3390/w16081111

- Griffiths H.J., Anker P., Linse K. et al. Breaking All the Rules: The First Recorded Hard Substrate Sessile Benthic Community Far Beneath an Antarctic Ice Shelf. Frontiers in Marine Science. 2021. Vol. 8. N 642040. DOI: 10.3389/fmars.2021.642040

- Vasilyev N.I., Leychenkov G.L., Zagrivny E.A. Prospects of Obtaining Samples of Bottom Sediments from Subglacial Lake Vostok. Journal of Mining Institute. 2017. Vol. 224, p. 199-208. DOI: 10.18454/PMI.2017.2.199

- Siegert M.J., Ross N., Le Brocq A.M. Recent advances in understanding Antarctic subglacial lakes and hydrology. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A. 2016. Vol. 374. Iss. 2059. N 20140306. DOI: 10.1098/rsta.2014.0306

- Bulat S.A. Microbiology of the subglacial Lake Vostok: first results of borehole-frozen lake water analysis and prospects for searching for lake inhabitants. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A. 2016. Vol. 374. Iss. 2059. N 20140292. DOI: 10.1098/rsta.2014.0292

- Ignatiev S.A., Vasilev D.A., Bolshunov A.V. et al. Experimental Research of Ice Cuttings Transport by Air While Drilling of the Snow-Firn Layer. Ice and Snow. 2023. Vol. 63. N 1, p. 141-152. DOI: 10.31857/S2076673423010076

- Bolshunov A.V., Vasilev D.A., Ignatiev S.A. et al. Mechanical drilling of glaciers with bottom-hole scavenging with compressed air. Ice and Snow. 2022. Vol. 62. N 1, p. 35-46 (in Russian). DOI: 10.31857/S2076673422010114

- Korobov G.Y., Vorontsov A.A. Study of conditions for gas hydrate and asphaltene-resin-paraffin deposits formation in mechanized oil production. Bulletin of the Tomsk Polytechnic University. Geo Аssets Engineering. 2023. Vol. 334. N 10, р. 61-75 (in Russian).

- Bolobov V., Martynenko Y., Yurtaev S. Experimental Determination of the Flow Coefficient for a Constrictor Nozzle with a Critical Outflow of Gas. Fluids. 2023. Vol. 8. Iss. 6. N 169. DOI: 10.3390/fluids8060169

- Shishkin Е.V., Bolshunov А.V., Timofeev I.P. et al. Model of a walking sampler for research of the bottom surface in the subglacial lake Vostok. Journal of Mining Institute. 2022. Vol. 257, p. 853-864. DOI: 10.31897/PMI.2022.53

- Litvinenko V., Trushko V. Modelling of geomechanical processes of interaction of the ice cover with subglacial Lake Vostok in Antarctica. Antarctic Science. 2025. Vol. 37. Iss. 1, p. 39-48. DOI: 10.1017/S0954102024000506

- Talalay P.G. Mechanical Ice Drilling Technology. Springer, 2016, p. 284. DOI: 10.1007/978-981-10-0560-2

- Triest J., Alemany O. Drill fluid selection for the SUBGLACIOR probe: a review of silicone oil as a drill fluid. Annals of Glaciology. 2014. Vol. 55. Iss. 68, p. 311-321. DOI: 10.3189/2014AoG68A028

- Solomon S., Ivy D.J., Mills M.J. et al. Emergence of healing in the Antarctic ozone layer. Science. 2016. Vol. 353. Iss. 6296, p. 269-274. DOI: 10.1126/science.aae0061

- Sukhanov A., Gansheng Yang, Vishniakov R., Vasilev N. The electromechanical drill penetrates the subglacial lake Vostok – A Case Study. Oil Gas European Magazine. 2020. Vol. 46. Iss. 2, p. 12-16. DOI: 10.19225/200611

- Michaud A.B., Vick-Majors T.J., Achberger A.M. et al. Environmentally clean access to Antarctic subglacial aquatic environments. Antarctic Science. 2020. Vol. 32. Iss. 5, p. 329-340. DOI: 10.1017/S0954102020000231

- Serbin D.V. Prevention of emulsion formation during opening subglasial reservoirs. News of the Ural State Mining University. 2021. Iss. 3 (63), p. 80-88 (in Russian). DOI: 10.21440/2307-2091-2021-3-80-88

- Vasilev N.I., Timofeev I.P., Bolshunov A.V. et al. Extension-Type Pulling-and-Running Gear for Investigations of Subglacial Lake Vostok. International Journal of Engineering and Technology. 2017. Vol. 9. N 4, p. 3330-3337. DOI: 10.21817/ijet/2017/v9i4/170904424

- Lipenkov V.Ya., Turkeev A.V., Ekaykin A.A. et al. Unsealing Subglacial Lake Vostok: Lessons and implications for future full-scale exploration. Arctic and Antarctic Research. 2024. Vol. 70. N 4, p. 477-498 (in Russian). DOI: 10.30758/0555-2648-2024-70-4-477-498

- Lukin V.V., Vasiliev N.I. Technological aspects of the final phase of drilling borehole 5G and unsealing Vostok Subglacial Lake, East Antarctica. Annals of Glaciology. 2014. Vol. 55. Iss. 65, p. 83-89. DOI: 10.3189/2014AoG65A002

- Gizatullin R., Dvoynikov M., Romanova N., Nikitin V. Drilling in Gas Hydrates: Managing Gas Appearance Risks. Energies. 2023. Vol. 16. Iss. 5. N 2387. DOI: 10.3390/en16052387

- Gaidukova O., Misyura S., Morozov V., Strizhak P. Gas Hydrates: Applications and Advantages. Energies. 2023. Vol. 16. Iss. 6. N 2866. DOI: 10.3390/en16062866

- Alekhina I., Ekaykin A., Moskvin A., Lipenkov V. Chemical characteristics of the ice cores obtained after the first unsealing of subglacial Lake Vostok. Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 2017. Vol. 461, p. 187-196. DOI: 10.1144/SP461.3

- Lipenkov V.Ya., Turkeev A.V., Vasilev N.I. et al. Melting temperature of ice and total gas content of water at the ice-water interface above subglacial Lake Vostok. Arctic and Antarctic Research. 2021. Vol. 67. N 4, p. 348-367 (in Russian). DOI: 10.30758/0555-2648-2021-67-4-348-367

- Fourteau K., Martinerie P., Faïn X. et al. Estimation of gas record alteration in very low-accumulation ice cores. Climate of the Past. 2020. Vol. 16. Iss. 2, p. 503-522. DOI: 10.5194/cp-16-503-2020

- Talalay P.G. Perspectives for development of ice-core drilling technology: a discussion. Annals of Glaciology. 2014. Vol. 55. Iss. 68, p. 339-350. DOI: 10.3189/2014AoG68A007

- Qinglei Wang, Huanrui Zhang, Zili Cui et al. Siloxane-based polymer electrolytes for solid-state lithium batteries. Energy Storage Materials. 2019. Vol. 23, p. 466-490. DOI: 10.1016/j.ensm.2019.04.016

- Xiao-ying Zhang, Pei-ying Zhang. Polymersomes in Nanomedicine – A Review. Current Nanoscience. 2017. Vol. 13. Iss. 2, p. 124-129. DOI: 10.2174/1573413712666161018144519

- Bohan Zhang, Jianfu Ma, Khan M.A. et al. The Effect of Economic Policy Uncertainty on Foreign Direct Investment in the Era of Global Value Chain: Evidence from the Asian Countries. Sustainability. 2023. Vol. 15. Iss. 7. N 6131. DOI: 10.3390/su15076131

- Barykin S.E., Sergeev S.M., Provotorov V.V. et al. Sustainability Analysis of Energy Resources Transport Based on A Digital N-D Logistics Network. Engineered Science. 2024. Vol. 29. N 1093. DOI: 10.30919/es1093