Experience of using low- and medium-frequency ground penetrating radars to study the internal structure of a glacier and the bedrock topography in the Schirmacher Oasis area, East Antarctica

- 1 — Ph.D. Associate Professor Saint Petersburg State University ▪ Orcid ▪ Scopus ▪ ResearcherID

- 2 — Senior Lecturer Saint Petersburg State University ▪ Orcid

- 3 — Geophysical Technician All-Russian Geological Research Institute of A.P. Karpinsky ▪ Orcid

- 4 — Ph.D., Dr.Sci. Leading Engineer VNIIOkeangeologia ▪ Orcid

Abstract

During the expeditionary research of 2023-2024 in the conditions of thick Antarctic ice sheet, the medium- and low-frequency ground penetrating radars (GPR) OKO-3 with a 150 MHz antenna and Triton-M with an extendable 25-50-100 MHz antenna (LOGIS LLC, Russia) improved and adapted for glacier investigations were tested for the first time. An example of the ice sheet study in the Schirmacher Oasis area showed that the OKO-3 GPR allows obtaining detailed information on the internal structure of the ice sheet to depths of about 200 m and successfully solving glacial stratigraphy issues. The Triton-M GPR has proven itself well for mapping the roof of underlying rocks to depths of 250-300 m. The article presents new data on the glacier structure in the Novo Runway area, as well as information on the glacier thickness and the subglacial rock base topography near the Schirmacher Oasis (Novolazarevskaya and Maitri stations). Typical structures of the glacier strata in this area are gently sloping layers and steep folds that replace them, complicated by crevasses. The subglacial topography to the south of the oasis is quite gentle. Individual uplifts and depressions do not exceed 30 m. The interface between the ice and the rock base was recorded over a distance of 4.5 km to the south of the oasis. In the east, about a kilometre from the last rock outcrop, the oasis is limited by a sharp depression in the bed. New data opens up the possibility of constructing the ice sheet models, studying its dynamics and evolution, and finding patterns in the crevasse formation.

Introduction

Russian (former Soviet) radio-echo sounding (RES) research in Antarctica began in February 1964, when employees of the Arctic and Antarctic Research Institute (AARI) conducted the first experiments to study the electromagnetic waves propagation in a glacier body [1]. Since then, this method has been successfully used on the sixth continent to study the glacier structure, the subglacial topography, and to determine the state of the subglacial medium, including the presence of water bodies [1-3].

Later on, portable subsurface sounding radars (ground penetrating radar, GPR) were developed, which have a smaller penetration depth, but significantly greater detail. High resolution and mobility of GPR enabled to solve many urgent issues of ensuring the safety of logistics operations in Antarctica. The GPR make it possible to study the structure of a glacier and snow-firn layer, to identify and outline dangerous zones of glacial crevasses, snow swamps, snow puddles, and other hydrography features of oases for the prompt assessment of the state of transport hubs and communication routes [4-6].

In addition to deep radar studies of features under kilometre-thick ice layers and, on the contrary, very detailed GPR near-surface surveys using high-frequency antennas, special attention should be paid to glacier studies in the medium depth range (first hundreds of metres) using medium- and low-frequency antennas from 25 to 150 MHz. The data obtained make it possible to study the internal structure of glacier strata and to construct their 3D models. It becomes possible to map folded structures in the glacier and faults in them by tracing marker horizons, to correlated fold elements and crevasse areas, to identify and outline individual ice flows and zones of their junction. These data provide a background for modelling the processes occurring in glaciers. Such GPR, in addition to the internal structure of the glacier, allow for mapping the subglacial topography, which is of key importance in the formation of layers in glacier strata. The ice flow direction, the crevasse occurrence probability, and the englacial channel development depend on it. An idea of the ice sheet thickness is important as it is and is primary information required for mathematical modelling of glacier dynamics and heat and mass transfer in it [7-9]. In addition, mapping the subglacial topography is also an urgent task to ensure the safety of transport operations and the placement of infrastructure. In areas with smooth near-horizontal limits of underlying rocks, unbroken ice layers are highly likely. They seem to be the most stable and safe areas. On the contrary, pronounced topography, elevation differences, large inclination angles of the rock base walls are prerequisites for deformations and various fault types in the glacier body, hindering its use for organizing communication routes, constructing facilities, etc. However, mapping the subglacial topography with the required degree of detail is not simple. High ice resistance [10] and significant depths exclude the use of electrical resistivity tomography. Complex conditions for the excitation of elastic vibrations limit the use of shallow seismic exploration. Magnetotelluric prospecting, transient electromagnetic method, and other electromagnetic techniques with ungrounded lines based on the diffusion equation do not provide the required detail. The most suitable method for solving the issue at hand is GPR with low-frequency antennas and equipment with a long record length.

In this article, the authors share their experience in using two GPR developed by LOGIS LLC (Russia) on the Antarctic ice sheet: OKO-3 with a shielded AB-150 antenna (central frequency 150 MHz) and Triton-M with telescopic unshielded 25-50-100 MHz antennas.

A brief overview of radar research in Antarctica

Ice-penetrating radars have been used to study glaciers since the middle of the last century. The first Russian (former Soviet Union) studies on the application of this method were conducted at Mirny Station in February 1964 by employees of the Ice and Ocean Physics Department of the AARI. Two years later, the first experiments were conducted with a radar installed on board an Il-14 aircraft. In February 1968, the first our areal airborne radar survey was carried out on Enderby Land. In 1967, AARI developed the first Russian (former Soviet) ice-penetrating radar for studying thick polar glaciers, the RLS-60-67 [1]. Similar foreign studies were conducted by the Scott Polar Research Institute (SPRI) employees in December 1963 on the Brunt Ice Shelf [11].

Since the 1970s, RES research has become the main method for studying glaciers and the subglacial medium, surpassing seismic exploration, which was used before. The main advantage of radar is its efficiency, especially in the airborne version. Currently, almost all of Antarctica, with the exception of certain internal areas, is covered by radar research, which provides a fairly accurate idea of the ice thickness and the subglacial topography [12]. Typically, metre-range frequencies are used for research on thick glaciers. This is due to acceptable attenuation in the glacier (which depends on the frequency) and the size of the antennas, which are critical for mounting on an aircraft. In Russian practice, RES research with a sounding pulse frequency of 60 MHz have been used for a long time. Recently, a device with a frequency of 130 MHz has been used. A comprehensive review of these types of research is given in [1, 3] and other papers.

Ice-penetrating radars, with their high power (to 80 kW) and a fairly broad pulse (to 1 μs), allow successful locating of multi-kilometre glaciers. However, for the same reasons, they cannot provide detailed studies of the near-surface part, while it is of significant interest both for glaciology and for solving engineering issues, in particular, ensuring the transport operations safety by identifying crevasses in the glacier body. For this purpose, GPR are used, which have a much lower power and the sounding pulse duration. After the discovery of Lake Vostok [13, 14], the radar method is actively used to identify and study subglacial water bodies [15-18].

High-frequency GPR (400-900 MHz) proved themselves well for studying the upper part of a glacier to a depth of 20 m. The first examples of their successful application were given in the works of foreign authors and relate to studies of both Antarctic and mountain glaciers [2, 19, 20]. Since 2013, GPR have been regularly used by the Russian Antarctic Expedition (RAE) experts to ensure the transport operations safety, construction of infrastructure facilities, and other engineering tasks. GPR studies are part of glacier engineering surveys, where they occupy a leading place among other techniques. GPR with antennas of the specified frequencies provide for detecting crevasses and determining their morphology, assessing the thickness of ice above water bodies, marking and outlining dangerous zones on glaciers and snow-firn strata. As an example, we can cite the work on selecting a site for the construction of an airfield at Mirny Station, identifying crevasses in sections of the route of the Progress – Vostok logistic traverse, and studying a lake that formed at the site of a large depression in the Dålk Glacier in the Progress Station area [21, 22].

Near the Progress Station, GPR studies have been conducted for several years. They enabled to organize a safe route between the station and the airfield [1], select sites for a fuel storage depot, and survey a section of the glacier for crevasses where scientific expedition vessels are unloaded [23]. High-frequency GPR also helps to build airbases in Antarctica, including both searching for suitable sites for subsequent construction and surveying existing runways [24, 25]. Examples include monitoring the international Novo Runway [26], construction of the new Zenit runway near the Progress Station, searching for safe sites on the glacier for building airfields near the Russkaya and Mirny stations, as well as the Bunger Hills field camp. In addition, GPR provides important assistance in the study of permafrost, including in Antarctica [27-29].

In comparison with powerful ice-penetrating radars providing depths of hundreds and even a few thousand metres, as well as high-frequency antennas used for detailed study of the upper section, undeservedly little attention is paid to low- and medium-frequency radars with a central frequency range of 25-150 MHz. They make it possible to study in detail the glacial strata structure to depths of about 200 m, to obtain data on the morphology of lake basins with a water column thickness of several tens of metres, to map the subglacial rock base at depths of 250-300 m [30, 31]. These data provide a background for modelling glaciers and snow-firn layers, which help in studying the dynamics and evolution of such media.

For example, in the Maitri Station area (Schirmacher Oasis, East Antarctica), Indian colleagues managed to obtain a reflection from the bottom of Lake L-75 at a depth of 34 m, as well as a reflection from the roof of rocks below the glacier at a depth of about 180 m using a GPR with an 80 MHz antenna [32].

Since 2017, RAE researchers have been carrying out work on the Boulder – Ledyanoe – Dålk lake system, as well as on the sinkhole formed on Lake Dålk site (Progress-1 field base area, Larsemann Hills). The work involved GPR with a set of antennas of different frequencies: 900, 500, 200, 150, and 75 MHz. To obtain bottom reflections in the deepest depressions of these lakes, an antenna with a frequency of 75 MHz was used. Thus, reflections were recorded on Lake Boulder at a water thickness of more than 40 m [22]. New data on Lake Progress structure, in particular its subglacial part, were obtained using 500 and 38 MHz antennas [33].

The paper [29] presents the results of work with the GSSI SIR-20 GPR at a sounding pulse frequency of 100 MHz at the boundary of the ice cap with the Larsemann Hills oasis, aimed at mapping the roof of the bedrock beneath the glacier. The maximum possible sounding depth was 89 m, the maximum depth of the identifiable glacier strata was 75 m. The authors [29] noted the possibility of identifying areas of meltwater accumulation in depressions in the rock topography when analysing the wave field.

The VIRL-7 GPR (20 MHz) is successfully used to study mountain glaciers in the Pamirs, Caucasus, and Polar Urals. In [34], based on VIRL-7 GPR surveys, the change of the Abramov Glacier volume in the Pamirs was evaluated over the past 32 years. The maximum ice thickness was 219 m. Similar work assessed the ice thickness change on Elbrus for the period from 1997 to 2017 using the VIRL-6 GPR (20 MHz) mounted on a helicopter [35]. The maximum ice thickness obtained by the authors on the Bolshoy Azau Glacier was 237±12.6 m.

GPR with antennas of different frequencies are actively and successfully used in the Svalbard glaciers study. In particular, the Pulse Ekko GPR with a 50 MHz antenna enables to obtain reflections from interfaces in the glacier at depths greater than 250 m. The authors of [36-38] show positive experience in mapping the underlying rock base, studying the distribution of warm ice fragments in the glacier body, and identifying englacial channels. The GPR method makes a significant contribution to the study of glaciers and soil in Greenland [39, 40], as well as Iceland and the islands of the Canadian Archipelago [41, 42].

Work area and research targets

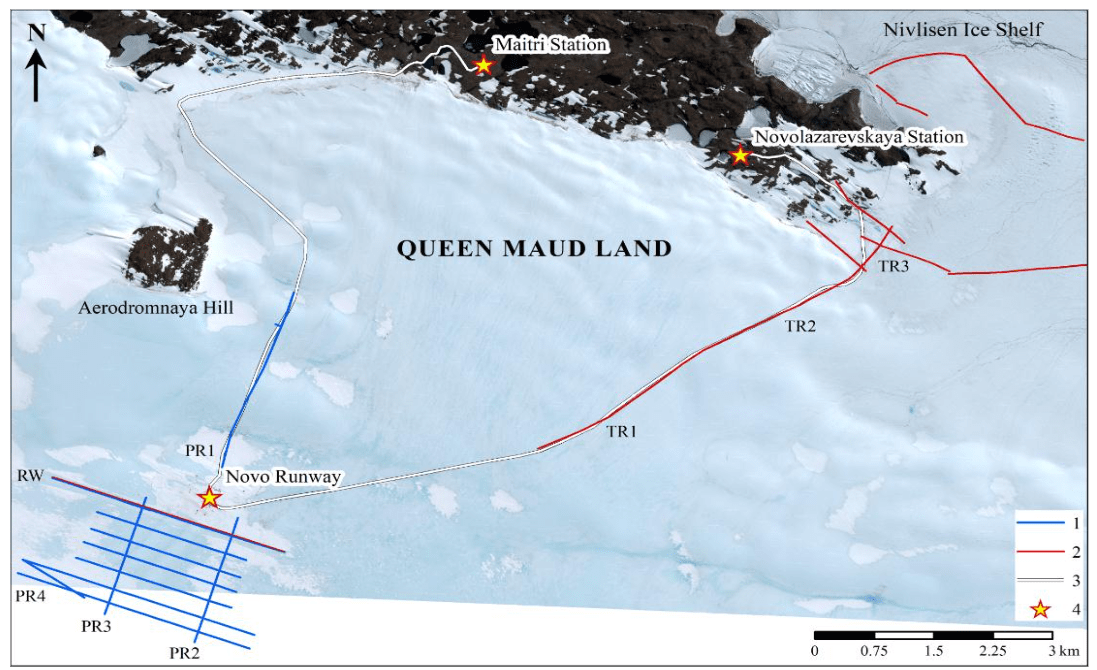

The work area is in the vicinity of the Schirmacher Oasis (East Antarctica), including its eastern end, as well as the area to the south, where on the ice cap, approximately 7 km from the oasis, there is a Novo Runway (Fig.1). The study targets were the subglacial rock base in the continuation of the Schirmacher Oasis and the ice cap itself.

The topography mapping of the subglacial rock base was performed along a system of routes located to the east of the oasis, as well as to the south along the tracks connecting the Russian Novolazarevskaya Station and the Indian Maitri Station with the Novo Runway. During this work, the lines passed from the rock outcrops of the Schirmacher Oasis and near Aerodromnaya Hill for reliable mapping of the subglacial surface. The lines began in areas with a smooth topography at the places of rock outcrops in order to avoid lateral reflections from steeply dipping rock walls. For the same reason, the routes did not pass near the vertical walls of the ice cap. Regular gridding of the line was hampered by the abundance of rivers and streams that eroded channels in the glacier more than 1 m deep, as well as the presence of snow swamps in the lowlands. The elevation difference on the line along the route to the runway (route TR1) was about 270 m from absolute elevations of 144 to 157 m in the southeastern part of the oasis to the 420 m mark 4.8 km south on the ice cap. In the E-W direction, the elevations changed insignificantly, the maximum difference was 14 m.

Fig.1. Area of GPR lines

1 – lines made by the OKO-3 GPR, AB-150 antenna; 2 – lines made by the Triton-M GPR, 25 MHz antenna; 3 – route; 4 – infrastructure facilities

Along the runway itself, where the absolute marks of the daylight surface are from 548 to 570 m, the reflection from the rock base was not recorded on the radar images due to the large thickness of the ice sheet. During the 67th RAE season (November – December 2021), the authors obtained the first data on the internal structure of the glacier within the runway and in the vicinity of it. Then, the ice flow junction zone and the fold systems adjacent to it from the west and east were found. During the present study, in the 69th RAE season (December 2023 – February 2024), the authors selected the specified area for test assessment of the discussed equipment capabilities for studying the internal structure of the glacier to depths of 150 m, including mapping of folded structures and other features.

Equipment, methods of field work and data processing

The Triton-M GPR with an unshielded 25-50-100 MHz extendable antenna and the improved OKO-3 GPR with a 150 MHz shielded antenna with a long record length, adapted for glacier studies, were tested for the first time in a thick Antarctic ice sheet conditions. The GPR survey started with the field trial. It was aimed at selecting the equipment (radar type and central frequency of antennas) and survey modes (number of accumulations, wheel calibration, sweep time, number of points per route, etc.). The goal was to compare the equipment and select the optimal parameters for mapping the subglacial topography and studying the internal structure of the glacier at depths exceeding 100 m.

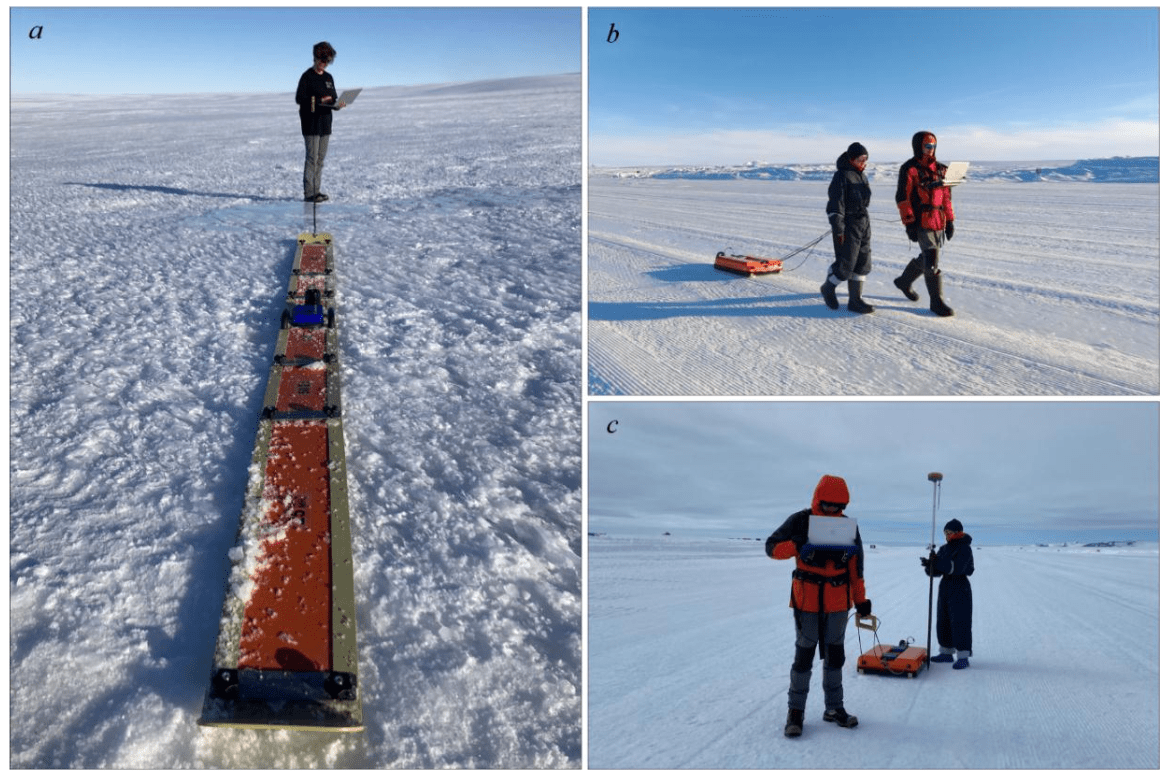

The survey was carried out on foot (Fig.2). When working with Triton-M, the recording was made in continuous mode (Fig.2, a). When working with the OKO-3 GPR with a 150 MHz antenna, an odometer was used to increase accuracy, which ensured uniform data recording along the route every 10 cm (Fig.2, b). GPR routes were positioned by the EFT M2 GNSS DGPS complex (Fig.2, c), and when the distance from the geodetic point at Novolazarevskaya Station was more than 3 km, by the Garmin GPSMap 64st satellite receiver using GPS and GLONASS navigation satellites. Since the survey took place in conditions of rugged terrain and significant elevations, planar and altitude referencing was made at defined topographic points every 100 m. Such points were marked in the radar images using the “marker” tool. Further, during office processing after interpolation, each route acquired its own coordinate. This method ensures referencing accuracy of the sought features to the first tens of centimetres. Processing and construction of deep sections considered the heights of the day surface.

Data recording and subsequent processing were performed in the CartScan and Geoscan32 software (Logic Systems LLC, Russia) using a standard procedure, which included removing stopping places, adjusting the line length in accordance with satellite referencing, adjusting brightness, contrast, and gain, and in some cases filtering and introducing daylight surface topography.

The complexity of processing and subsequent interpretation of GPR data is often associated with the choice of a kinematic model of the medium, which determines the correct conversion of time sections to depth sections. In our case, the situation is simplified, since the work area is on blue ice, on which the snow cover is either absent or insignificant. Thus, the GPR section is converted to a depth section in a model of a homogeneous medium with a permittivity of ε = 3.17, which corresponds to the propagation speed of electromagnetic waves of 16.8 cm/ns. The estimate of ε of ice was based on numerous diffracted wave travel time curves in the glacier and the common depth point (CDP) method. The CDP was used with the OKO-2 GPR with AB-150 extendable antennas. The generator and receiving antennas were spaced symmetrically relative to the centre with a step of 0.5 m. The maximum spacing was 20 m. The CDP arrangements were in areas with horizontal limits of the subglacial rock base, for which a GPR survey was previously carried out along a system of perpendicular lines. The obtained values of the permittivity and, accordingly, the propagation speed of electromagnetic waves, are in good agreement with similar characteristics of ice considered in [43, 44]. The depth of limits within the glacier under study were repeatedly confirmed by auger drilling when studying lakes covered by ice and englacial tunnels. The error was no more than 3-4 %.

Fig.2. Survey in the Novo Runway area

Triton-M GPR

The shape and structure of the Triton-M GPR antenna (an extendable flexible monoski) allow it to be easily moved along the glacier surface, passing around snowdrifts, zastrugas, and other obstacles. Another advantage is the absence of wires, cables, and other connections that greatly complicate work in conditions of low temperatures, snow, and strong wind. The autonomous recording and control unit is connected to a laptop via Wi-Fi. During the work, various combinations of survey parameters were tested: the sounding pulse frequency, the record length, the number of points per route.

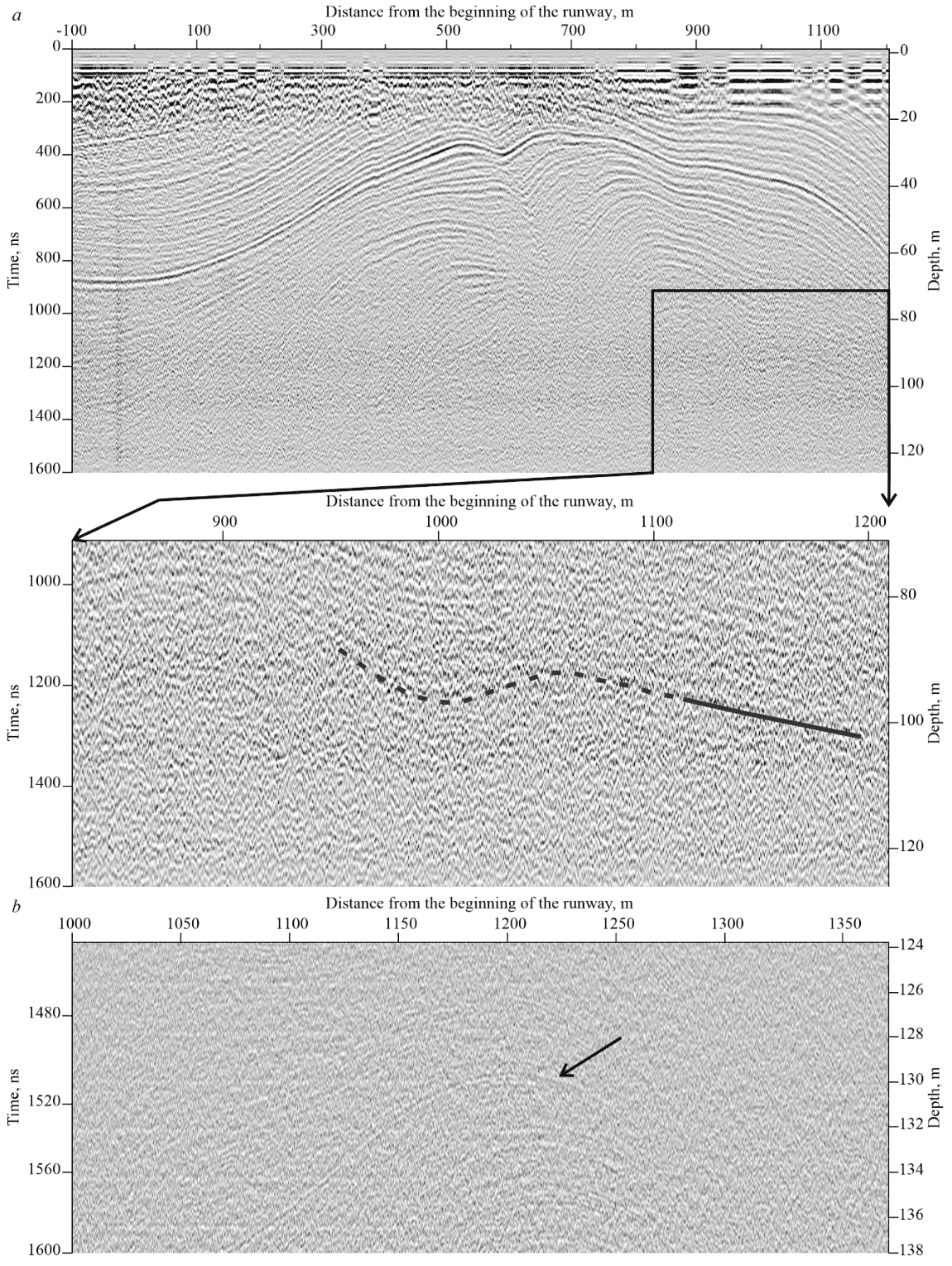

A survey with a 25 MHz antenna, a 1,600 ns sweep time, and 1,024 points per route was performed on the RW line along the runway axis over a 1,300 m segment from the starting point. The resulting radar image (Fig.3, a) shows that the first 100 ns, corresponding to a 9-metre ice strata, are noisy due to the low-frequency signal and contrast reflection, presumably from the operator. Nume-rous reverberations, also masking the upper part of the GPR section, correspond to minor crevasses, mostly healed. The crevasses are seasonal, appearing on open ice areas in spring (October – November) due to sharp day and night temperature changes. During the Antarctic summer, these minor crevasses fill with water, then freeze and, as a rule, completely heal.

Fig.3. GPR section along the RW line along the central axis of the runway: a – obtained by the Triton-M GPR with a 25 MHz antenna (the inset shows an enlarged section, in a square); b – obtained by the OKO-3 GPR, AB-150 antenna, the arrow indicates one of the layers in the glacier body

At long recording times, the glacier layering is clearly observed. Thus, to the 1,200 ns mark (depth of about 100 m), the patterns are still visible (Fig.3, a, inset). The layers observed in the radar images reflect ice accumulation and are poorly distinguishable by permittivity. The phenomenon of the intense reflections in radar images with weak differentiation of layers by electrophysical properties can be explained by the low attenuation of the electromagnetic wave in a homogeneous and high-resistance medium. Ice is exactly such a medium, where the presence of even minor inhomogeneities at the contact of two layers is sufficient to form a high-amplitude reflection. Such inhomogeneities can presumably be different densities of interlayers, mineral inclusions, as well as the shape, orientation, and size of crystals, which is explained by different weather conditions during the snow accumulation and its metamorphism. Thus, providing the minimal difference in permittivity in the glacier body layers, the obtained result can be considered quite satisfactory.

OKO-3 GPR

The improved OKO-3 GPR with the antenna monoblock AB-150 (see Fig.2, b) was tested in Antarctica for the first time. It allows setting a longer record length, proportionally increasing the number of points per route. This makes it much more suitable for studying glaciers and compares favourably with the previous generation OKO-2 equipment, where the record length was limited by the number of discrete points per route (512 points), which on a 1,600 ns sweep time made the radar image almost unreadable, the patterns were poorly traced, the layers were broken into rectangles.

Figure 3, b shows a fragment of the section along the RW route (central part), obtained with the OKO-3 GPR, AB-150 with a 1,600 ns sweep time and 2,048 points per route. Due to the weak attenuation of the electromagnetic wave in the continental ice and the absence of contrasting interfaces in the upper section, the signal amplitude is enough to form a clear reflected signal even at maximum recording times. Due to the high resolution provided by a sufficient number of samples and a powerful transmitter antenna, the layers in the glacier are clearly distinguishable at depths exceeding 130 m.

Comparison of the OKO-3 and Triton-M GPR for studying the internal structure of a glacier

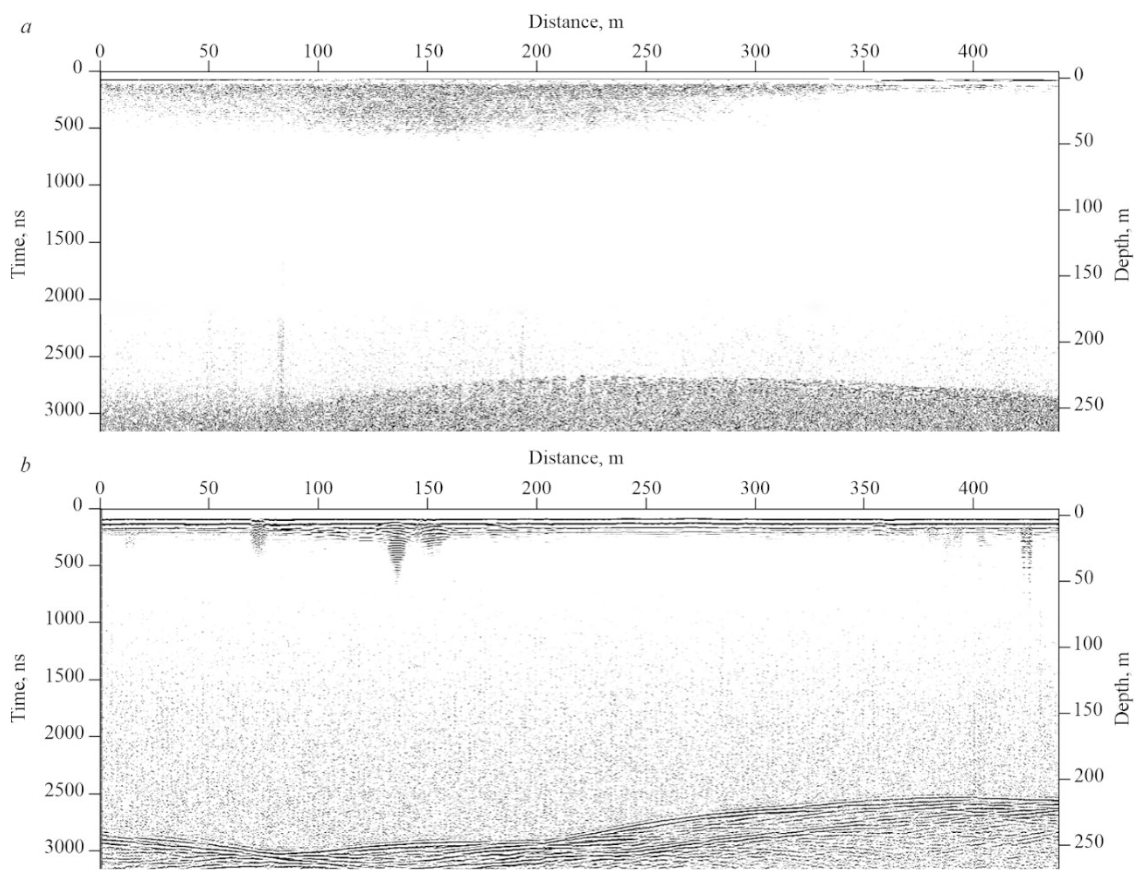

During the field trial, sections with a record length of 800 ns obtained on the same RW line section using the OKO-3 GPR with a 150 MHz antenna unit (Fig.4, a) and the Triton-M GPR with a frequency of 50 MHz were compared (Fig.4, b).

Due to the absence of contrasting interfaces in the glacier strata, an insignificant difference in the permittivity of the features under study, and often their minor sizes (ice layers differing in the degree of metamorphism and the presence of mineral inclusions; crevasses filled with air, snow, or healed with ice), the OKO-3 GPR with an AB-150 antenna is more effective for studying the internal structure of a glacier.

The AB-150 antenna unit, on the one hand, has a powerful generator, which ensures the required depth of investigation and allows, with the used sweep time, to confidently trace the internal structure of the glacier to a depth of 65 m. On the other hand, it has sufficient resolution (layers less than 0.5 m thick are distinguished in the horizontal and vertical directions). In both presented sections (Fig.4), folds and large structures are equally clearly traced. However, Triton-M radar images determine individual crevasses, their sizes and morphology much worse. Moreover, the unshielded antenna used in the Triton-M GPR records additional reflections from man-made metal features on the surface, such as metal fragments of runway markings and others (120 and 980 m from the starting point of the line), which represents additional interference and can mask useful information.

Fig.4. GPR sections along line RW

Comparison of OKO-3 and Triton-M GPR for bedrock mapping

The capabilities of the GPR using maximum sweep times (3,200 ns for Triton-M and 6,400 ns for OKO-3 with AB-150) for mapping the roof of underlying rocks were tested on two parallel N-S lines on an ice cap approximately 4 km south of the Schirmacher Oasis. The Triton-M GPR survey passed along route TR1 along the road connecting the Novolazarevskaya Station with the runway, and the OKO-3 GPR survey passed 4.5 km to the west (route PR1) along the road to the Maitri Station near Aerodromnaya Hill (see Fig.1).

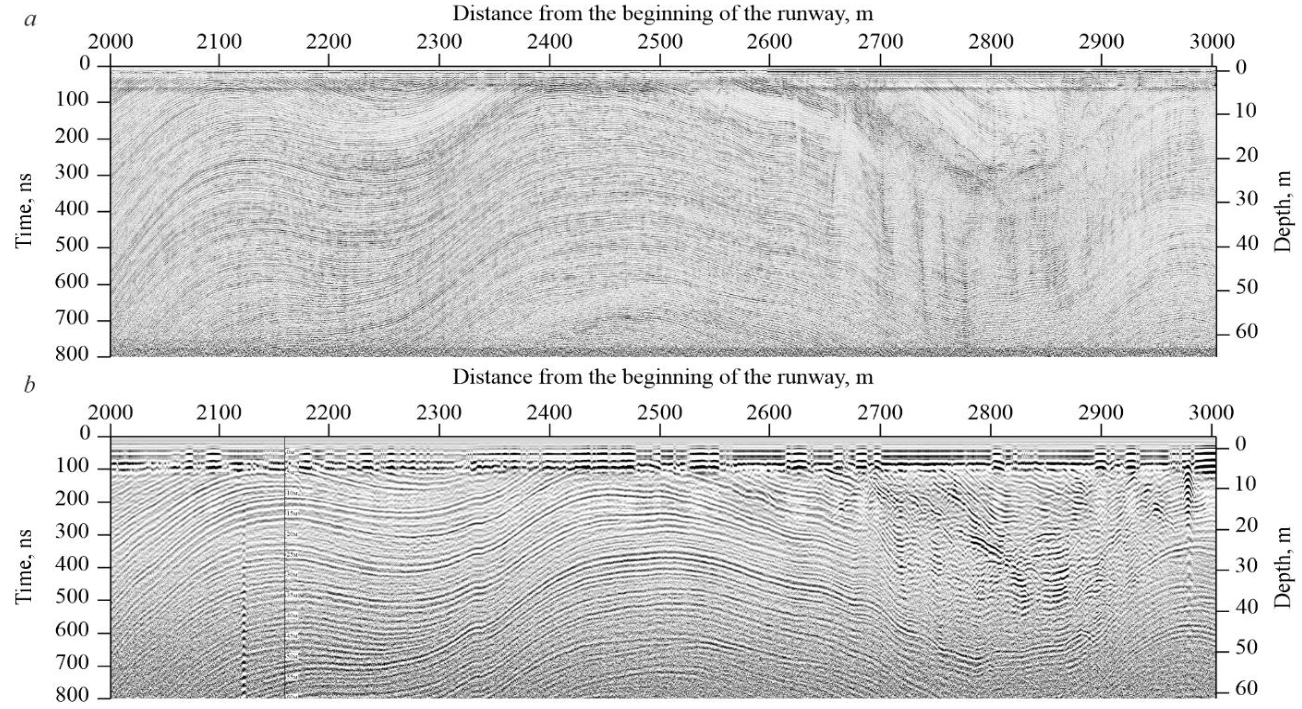

Figure 5 shows a comparison of GPR sections obtained with OKO-3 and Triton-M at the same ice sheet thickness (250-260 m), which corresponds to reflections from underlying rocks at 3,000-3,200 ns sweep time. As expected, the OKO-3 GPR emitted pulse power is inferior to that of the Triton-M GPR. In addition, the frequency of 150 MHz in this case seems too high compared to the frequency of 25 MHz. Reflections from the rock in the Triton-M GPR images remain clear, have high amplitude, and are perfectly traced against the background noise. Unfortunately, it was not possible to trace the reflection from the rock base deeper than 260 m, since the maximum sweep time of the Triton-M is 3,200 ns. OKO-3 radar images obtained at the same recording times and under similar conditions do not show such clear reflections. The useful signal/noise ratio is much inferior to those obtained with Triton-M. However, the use of OKO-3 can be recommended for cases when the Triton-M sweep time is insufficient. Thus, the maximum depth at which a reflection from a rock base was recorded with the OKO-3 AB-150 equipment was 320 m (1.7 km north of the runway). Deeper, the signal completely disappeared against the background noise.

Fig.5. Radar images obtained along parallel routes 4 km south of the southern limit of the Schirmacher Oasis: a – OKO-3 GPR survey result, 150 MHz antenna, fragment of line PR1; b – Triton-M GPR survey result, 50 MHz antenna, fragment of line TR1

Work results

Field trial aimed at selecting equipment and optimal survey modes showed that it is preferable to use the OKO-3 GPR with a 150 MHz antenna to study the internal structure of the glacier, and the Triton-M GPR with a 25 MHz antenna to map the topography of rocks below the ice sheet. The first practical results obtained by the authors using the selected equipment and survey methods show the structural features of the ice sheet to the south of the Schirmacher Oasis and the position of the rock roof below the ice cap in the vicinity of the oasis.

Structure of the near-surface part of the ice sheet near the Novo Runway

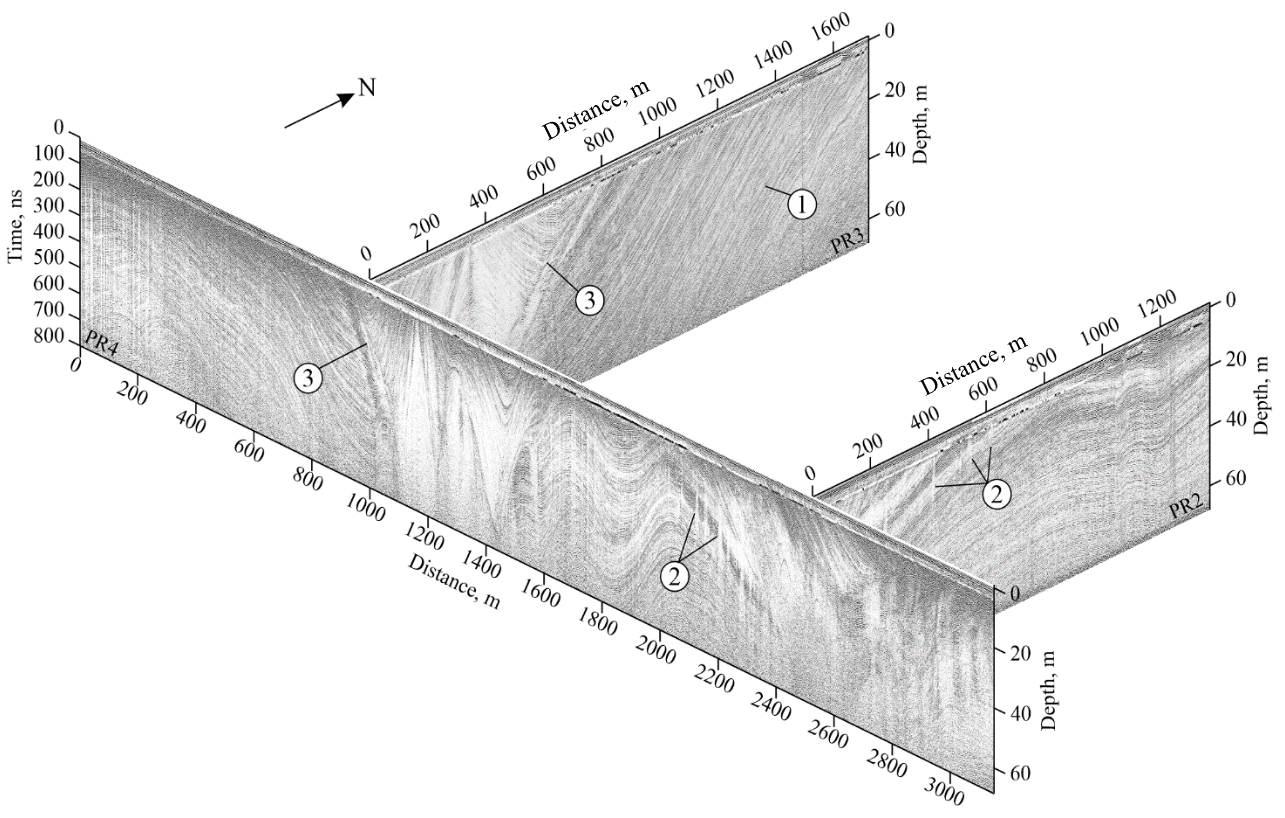

Areal GPR survey at 1:25,000 scale was performed on an area of 6 km2. Detailed results are presented in [26], which, based on GPR and geodetic surveys, assesses the safety of the operating runway, describes the internal structure of the glacier, and identifies the most stable and dynamically developing areas. This work presents only a fragment of the survey 2 km south of the Novo Runway (Fig.6) to show the OKO-3 GPR capabilities.

Fig.6. Internal structure of the ice sheet to a depth of 70 m according to GPR data to the south of the Novo Runway

1 – near-horizontal undisturbed strata; 2 – crevasses on the crest of the anticlinal fold; 3 – unconformable contact

On the N-S trending PR2 and PR3 lines, in the northern part, the glacier is represented by near-horizontal or low-angle undisturbed strata. This is where the runway is located. In the southern part of the lines, the glacier has a more complex structure. On the PR2 line, crevasses are clearly visible on the crest of the anticlinal fold, and on the PR3 line, an unconformably occurring synclinal fold of superimposed ice can be traced. On the E-W trending PR4 line, a folded structure is observed in the central part. The anticlinal dome-shaped folds characterized by local areas of extension are accompanied by a fairly large number of crevasses. Synclinal concave folds, corresponding to compression zones, do not comprise crevasses. The GPR section of the PR4 line also shows a near-vertical unconformable contact between the near-horizontal strata in the western part and the one crumpled into steep folds in the central and eastern parts of the line.

The folded structures are apparently related to the uneven movement of the glacier, which is confirmed by high-precision geodetic surveys [26], as well as the dissected topography of the underlying rock base, as evidenced by the presence of rock outcrops (nunataks) within a radius of 4-7 km, the slopes of which plunge sharply below the glacier. It has not yet been possible to map the subglacial topography in this particular area due to the limited record length of the GPR used. Further investigations to clarify the correlation between the internal structure of the glacier and the underlying rock base topography seems promising and interesting from a scientific and practical viewpoint.

Thus, areal GPR survey using the OKO-3 GPR makes it possible to examine the internal structure of the glacier in great detail, construct its 3D model, and make assumptions about the history of its development. By supplementing the obtained GPR sections with drilling results, including isotope analysis of the core, it is possible to move on to solving the glacial stratigraphy issues. Based on the characteristic wave pattern and clear marker horizons, it is possible to identify GPR facies, spatially tracing the strata of certain ages and formation conditions by analogy with seismic stratigraphy.

At the moment, there are no methods that enable to study any of the geological media with the same detail and to the same depth. Only a unique combination of the physical properties of ice and the GPR capabilities allows us to “look inside” the glacier and obtain a clear pattern of its internal structure.

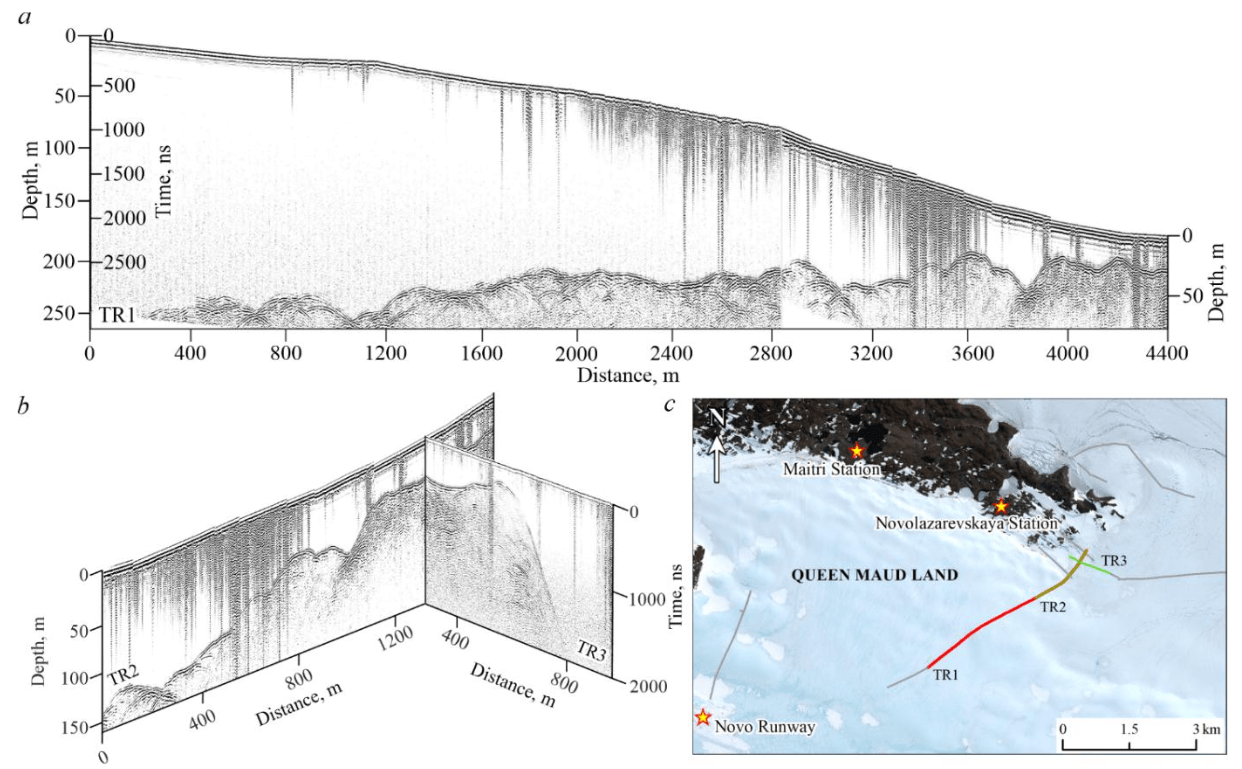

Subglacial topography near the Schirmacher Oasis

The rock base is clearly traced in the Triton-M radar images. The interface is very contrasting (Fig.7). Figure 7, a shows a fragment of the TR1 line 4,500 m long, running from the eastern end of the oasis towards the runway. Unfortunately, reverberations from the presence of water in the creek beds and near-surface englacial channels partially contaminate the radar images, especially near the oasis and on the ice cap slope. However, the reflection from the ice-rock interface is so contrasting even at the maximum possible sweep times that the reverberations did not prevent the target interface from being identified. Near the oasis, the rock can be traced at a depth of 20-40 m. Further, as one ascends the glacier, closer to the zero stacks, the interface is observed at a depth below 250 m from the day surface. Unfortunately, it was not possible to trace the reflection from the rock base deeper than 260 m, since the maximum sweep time of the Triton-M is 3,200 ns.

On the TR1 line, the subglacial topography is quite flat. Individual uplifts and depressions do not exceed 30 m. A slight topographic low is observed in the southwest direction. All additional routes passing in the runway direction did not yield results, since the rock base turned out to be below the maximum possible recording depth, which indicates the absence of sharp rises. On the perpendicular line TR3 passing in the eastern direction, a sharp depression of the subglacial base is observed. On a 200 m long segment, its roof descends from the –20 m mark to the –180 m mark. The GPR route shot with a 3,200 ns sweep time in continuation of line TR3 showed that the specified interface continues to descend at a steep angle and after about 100 m goes beyond the recording window, i.e. to a depth below 260 m.

The above line was extended 4.5 km to the east of the oasis to trace a possible re-uplift of the interface to the day surface. However, this did not happen, and the glacier is more than 260 m thick along its entire length. A similar pattern is observed on a parallel line located 2.5 km to the south. Thus, the Schirmacher Oasis is probably limited from the east by a steep fault.

Fig.7. Bedrock near the eastern end of the Schirmacher Oasis: a – along the road between the Novolazarevskaya Station and the runway; b – at the intersection of the road and the perpendicular east-trending line; c – position of GPR routes shown in Fig. a and b

Conclusions

The GPR survey showed the possibility of using both radar types both for studying the internal structure of the glacier to a depth of about 140 m and for mapping the roof of the underlying rock base to a depth of 250-300 m. However, the OKO-3 GPR with the AB-150 antenna makes it pos-sible to examine in more detail the glacier strata layering, its discontinuities, and the internal structure of the glacier as a whole. The Triton-M GPR with a frequency of 25 MHz is more suitable for studying the subglacial topography. At the maximum possible sweep time of 3,200 ns, which corresponds to a depth of 260 m, it shows clear reflections from the underlying rocks. Thus, the improved, with a long record length, medium- and low-frequency OKO-3 GPR with a 150 MHz antenna and Triton-M GPR with an extendable 25-50-100 MHz antenna have high resolution and provide the necessary depth of research. They have shown reliable results, are convenient to use in polar regions, and can be recommended for studying Antarctic ice caps to 250 m thick and similar features.

References

- Popov S. Fifty-five years of Russian radio-echo sounding investigations in Antarctica. Annals of Glaciology. 2020. Vol. 61. Iss. 81, p. 14-24. DOI: 10.1017/aog.2020.4

- Annan A.P. GPR Methods for Hydrogeological Studies. Hydrogeophysics. Springer, 2005. Vol. 50, p. 185-213. DOI: 10.1007/1-4020-3102-5_7

- Schroeder D.M., Bingham R.G., Blankenship D.D. et al. Five decades of radioglaciology. Annals of Glaciology. 2020. Vol. 61. Iss. 81, p. 1-13. DOI: 10.1017/aog.2020.11

- Taurisano A., Tronstad S., Brandt O., Kohler J. On the use of ground penetrating radar for detecting and reducing crevasse-hazard in Dronning Maud Land, Antarctica. Cold Regions Science and Technology. 2006. Vol. 45. Iss. 3, p. 166-177. DOI: 10.1016/j.coldregions.2006.03.005

- Tess X.H. Luo, Wallace W.L. Lai, Ray K.W. Chang, Goodman D. GPR imaging criteria. Journal of Applied Geophysics. 2019. Vol. 165, p. 37-48. DOI: 10.1016/j.jappgeo.2019.04.008

- Williams R.M., Ray L.E., Lever J.H., Burzynski A.M. Crevasse Detection in Ice Sheets Using Ground Penetrating Radar and Machine Learning. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing. 2014. Vol. 7. Iss. 12, p. 4836-4848. DOI: 10.1109/JSTARS.2014.2332872

- Pattyn F., Carter S.P., Thoma M. Advances in modelling subglacial lakes and their interaction with the Antarctic ice sheet. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A. 2016. Vol. 374. Iss. 2059. N 20140296. DOI: 10.1098/rsta.2014.0296

- Couston L-A., Siegert M. Dynamic flows create potentially habitable conditions in Antarctic subglacial lakes. Science Advances. 2021. Vol. 7. Iss. 8. N eabc3972. DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.abc3972

- Fürst J.J., Rybak O., Goelzer H. et al. Improved convergence and stability properties in a three-dimensional higher-order ice sheet model. Geoscientific Model Development. 2011. Vol. 4. Iss. 4, p. 1133-1149. DOI: 10.5194/gmd-4-1133-2011

- Johari G.P., Whalley E. The dielectric properties of ice Ih in the range 272-133 K. The Journal of Chemical Physics. 1981. Vol. 75. Iss. 3, p. 1333-1340. DOI: 10.1063/1.442139

- Evans S. Radio techniques for the measurement of ice thickness. Polar Record. 1963. Vol. 11. Iss. 73, p. 406-410. DOI: 10.1017/S0032247400053523

- Frémand A.C., Fretwell P., Bodart J.A. et al. Antarctic Bedmap data: Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable (FAIR) sharing of 60 years of ice bed, surface, and thickness data. Earth System Science Data. 2023. Vol. 15. Iss. 7, p. 2695-2710. DOI: 10.5194/essd-15-2695-2023

- Siegert M.J. A 60-year international history of Antarctic subglacial lake exploration. Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 2018. Vol. 461, p. 7-21. DOI: 10.1144/SP461.5

- Kapitsa A.P., Ridley J.K., Robin G. de Q. et al. A large deep freshwater lake beneath the ice of central East Antarctica. Nature. 1996. Vol. 381. Iss. 6584, p. 684-686. DOI: 10.1038/381684a0

- Livingstone S.J., Yan Li, Anja Rutishauser et al. Subglacial lakes and their changing role in a warming climate. Nature Reviews Earth & Environment. 2022. Vol. 3. Iss. 2, p. 106-124. DOI: 10.1038/s43017-021-00246-9

- Siegert M.J., Ross N., Le Brocq A.M. Recent advances in understanding Antarctic subglacial lakes and hydrology. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A. 2016. Vol. 374. Iss. 2059. N 20140306. DOI: 10.1098/rsta.2014.0306

- Siegert M.J., Priscu J.C., Alekhina I.A. et al. Antarctic subglacial lake exploration: first results and future plans. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A. 2016. Vol. 374. Iss. 2059. N 20140466. DOI: 10.1098/rsta.2014.0466

- Popov S.V., Boronina A.S., Ekaykin A.A. et al. Remote sensing and mathematical modelling of Lake Vostok, East Antarctica: past, present and future research. Arctic and Antarctic Research. 2024. Vol. 70. N 4, p. 460-476. DOI: 10.30758/0555-2648-2024-70-4-460-476

- Forte E., Bondini M.B., Bortoletto A. et al. Pros and Cons in Helicopter-Borne GPR Data Acquisition on Rugged Mountainous Areas: Critical Analysis and Practical Guidelines. Pure and Applied Geophysics. 2019. Vol. 176. Iss. 10, p. 4533-4554. DOI: 10.1007/s00024-019-02196-2

- Campbell S., Affleck R.T., Sinclair S. Ground-penetrating radar studies of permafrost, periglacial, and near-surface geology at McMurdo Station, Antarctica. Cold Regions Science and Technology. 2018. Vol. 148, p. 38-49. DOI: 10.1016/j.coldregions.2017.12.008

- Popov S.V., Polyakov S.P., Pryakhin S.S. et al. Structure of the upper part of the glacier in the area of the designed snow-runway of Mirny station, East Antarctica (based on the data compiled in 2014/15 field season). Earth’s Cryosphere. 2017. Vol. XXI. N 1, p. 73-84 (in Russian). DOI: 10.21782/KZ1560-7496-2017-1(73-84)

- Boronina A., Popov S., Pryakhina G. et al. Formation of a large ice depression on Dålk Glacier (Larsemann Hills, East Antarctica) caused by the rapid drainage of an englacial cavity. Journal of Glaciology. 2021. Vol. 67. Iss. 266, p. 1121-1136. DOI: 10.1017/jog.2021.58

- Grigoreva S.D., Kinyabaeva E.R., Kuznetsova M.R. Comprehensive monitoring program for geohazards in the Progress station area: main results of work in 2017-2021. Rossiiskie polyarnye issledovaniya. 2021. N 3, p. 13-15.

- Lili Cheng, Ji Lu, Cheng Zhou. Non-destructive compaction quality evaluation of runway construction based on GPR data. Nondestructive Testing and Evaluation. 2024. Vol. 39. Iss. 6, p. 1379-1406. DOI: 10.1080/10589759.2023.2255363

- Nansha Li, Renbiao Wu, Haifeng Li et al. MV-GPRNet: Multi-View Subsurface Defect Detection Network for Airport Runway Inspection Based on GPR. Remote Sensing. 2022. Vol. 14. Iss. 18. N 4472. DOI: 10.3390/rs14184472

- Boronina A.S., Kashkevich M.P., Popov S.V. et al. New data on the structure and motion of the ice sheet in the area of a runway of the Novolazarevskaya Research Station (East Antarctica). Ice and Snow. 2024. Vol. 64. N 3, p. 387-402 (in Russian). DOI: 10.31857/S2076673424030065

- Campbell S., Affleck R.T., Sinclair S. Ground-penetrating radar studies of permafrost, periglacial, and near-surface geology at McMurdo Station, Antarctica. Cold Regions Science and Technology. 2018. Vol. 148, p. 38-49. DOI: 10.1016/j.coldregions.2017.12.008

- Forte E., French H.M., Raffi R. et al. Investigations of polygonal patterned ground in continuous Antarctic permafrost by means of ground penetrating radar and electrical resistivity tomography: Some unexpected correlations. Permafrost and Periglacial Processes. 2022. Vol. 33. Iss. 3, p. 226-240. DOI: 10.1002/ppp.2156

- Jingxue Guo, Lin Li, Juncheng Liu et al. Ground-penetrating radar survey of subsurface features at the margin of ice sheet, East Antarctica. Journal of Applied Geophysics. 2022. Vol. 206. N 104816. DOI: 10.1016/j.jappgeo.2022.104816

- Dunmire D., Lenaerts J.T.M., Banwell A.F. et al. Observations of Buried Lake Drainage on the Antarctic Ice Sheet. Geophysical Research Letters. 2020. Vol. 47. Iss. 15. N e2020GL087970. DOI: 10.1029/2020GL087970

- Dugan H.A., Doran P.T., Tulaczyk S. et al. Subsurface imaging reveals a confined aquifer beneath an ice-sealed Antarctic lake. Geophysical Research Letters. 2015. Vol. 42. Iss. 1, p. 96-103. DOI: 10.1002/2014GL062431

- Swain A.K., Goswami S. Continuous GPR survey using Multiple Low Frequency antennas – case studies from Schirmacher Oasis, East Antarctica. International Journal of Earth Sciences and Engineering. 2014. Vol. 7. N 4, p. 1623-1629.

- Grigoreva S.D., Kuznetsova M.R., Kiniabaeva E.R. New data on Progress Lake (Larsemann Hills, East Antarctica): Recently discovered subglacial part of the basin. Polar Science. 2023. Vol. 38. N 100925. DOI: 10.1016/j.polar.2023.100925

- Saks T., Rinterknecht V., Lavrentiev I. et al. Acceleration of Abramov Glacier (Pamir-Alay) retreat since the Little Ice Age. Boreas. 2024. Vol. 53. Iss. 3, p. 415-429. DOI: 10.1111/bor.12659

- Kutuzov S., Lavrentiev I., Smirnov A. et al. Volume Changes of Elbrus Glaciers From 1997 to 2017. Frontiers in Earth Science. 2019. Vol. 7. N 153. DOI: 10.3389/feart.2019.00153

- Borisik A.L., Novikov A.L., Glazovsky A.F. et al. Structure and dynamics of Aldegondabreen, Spitsbergen, according to repeated GPR surveys in 1999, 2018 and 2019. Ice and Snow. 2024. Vol. 61. N 1, p. 26-37 (in Russian). DOI: 10.31857/S2076673421010069

- Borisik A.L., Demidov V.E., Romashova K.V., Novikov A.L. Internal drainage network and characteristics of the Aldegondabreen runoff (West Spitsbergen). Arctic and Antarctic Research. 2021. Vol. 67. N 1, p. 67-88 (in Russian). DOI: 10.30758/0555-2648-2021-67-1-67-88

- Terekhov A.V., Verkulich S., Borisik A. et al. Mass balance, ice volume, and flow velocity of the Vestre Grønfjordbreen (Svalbard) from 2013/14 to 2019/20. Arctic, Antarctic, and Alpine Research. 2022. Vol. 54. Iss. 1, p. 584-602. DOI: 10.1080/15230430.2022.2150122

- Nielsen L., Bendixen M., Kroon A. et al. Sea-level proxies in Holocene raised beach ridge deposits (Greenland) revealed by ground-penetrating radar. Scientific Reports. 2017. Vol. 7. N 46460. DOI: 10.1038/srep46460

- Lamsters K., Karušs J., Krievāns M., Ješkins J. High-Resolution surface and BED topography mapping of Russell Glacier (SW Greenland) using UAV and GPR. ISPRS Annals of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences: XXIV ISPRS Congress, Commission II, 31 August – 2 September 2020, Nice, France. 2020. Vol. V-2-2020, p. 757-763. DOI: 10.5194/isprs-annals-V-2-2020-757-2020

- Wilken D., Wunderlich T., Zori D. et al. Integrated GPR and archaeological investigations reveal internal structure of man-made Skiphóll mound in Leiruvogur, Iceland. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports. 2016. Vol. 9, p. 64-72. DOI: 10.1016/j.jasrep.2016.07.005

- Harrison D., Ross N., Russell A.J., Jones S.J. Ground-penetrating radar (GPR) investigations of a large-scale buried ice-marginal landsystem, Skeiðarársandur, SE Iceland. Boreas. 2022. Vol. 51. Iss. 4, p. 824-846. DOI: 10.1111/bor.12587

- Glazovsky A.F., Macheret Yu.Ya. Water in glaciers. Methods and results of geophysical and remote sensing studies. Moscow: GEOS, 2014, 528 p. (in Russian).

- Galley R.J., Trachtenberg M., Langlois A. et al. Observations of geophysical and dielectric properties and ground penetrating radar signatures for discrimination of snow, sea ice and freshwater ice thickness. Cold Regions Science and Technology. 2009. Vol. 57. Iss. 1, p. 29-38. DOI: 10.1016/j.coldregions.2009.01.003