Pegmatites of the Larsemann Hills oasis, East Antarctica: new field geological and geophysical data

- 1 — Postgraduate Student Empress Catherine II Saint Petersburg Mining University ▪ Orcid

- 2 — Ph.D., Dr.Sci. Head of Department Empress Catherine II Saint Petersburg Mining University ▪ Orcid

- 3 — Leading Engineer Empress Catherine II Saint Petersburg Mining University ▪ Orcid

- 4 — Leading Engineer Empress Catherine II Saint Petersburg Mining University ▪ Orcid

Abstract

This paper presents new data on various types of pegmatites from the Larsemann Hills oasis (Princess Elizabeth Land, East Antarctica), collected during the 70th Russian Antarctic Expedition in 2024-2025. As a result of comprehensive geological and geophysical investigations, all pegmatite occurrences in the area belonging to different stages of the Pan-African orogeny have been described, analyzed, and systematically classified in a unified context for the first time. In addition to previously known pegmatites associated with deformation stages D2-3, D4, and post-D4, a further subdivision is proposed based on mineralogical-geochemical characteristics and the content of natural radionuclides. These include borosilicate D2-3 pegmatites, rare-metal D4 pegmatites, muscovite-bearing post-D4 pegmatites, as well as two newly identified types not previously described in the region: K-feldspar D4' pegmatites and miarolitic rare-metal post-D4' pegmatites, which differ in morphology, mineralogy, and geochemical features. Special attention is given to the structural-tectonic control of pegmatite bodies, their geological setting, zoning patterns, and the results of gamma spectrometric and magnetic surveys. Pegmatitic formations containing rare typomorphic minerals – such as tourmaline, boralsilite, grandidierite, and chrysoberyl – are also examined. The results indicate a significant diversity of pegmatite formation conditions, help refine the PT parameters and timing of the initial and final stages of the Pan-African metamorphic event, and confirm the genetic link between pegmatite development and D2-D4 deformation stages. These findings contribute to the reconstruction of Early Paleozoic pegmatite-forming stages during anatectic processes in the geodynamic evolution of East Antarctica and Gondwana.

Funding

This research was carried out with support from the State assignment grant for scientific research in 2024 (N FSRW-2024-0003).

Introduction

Pegmatites are highly differentiated late-magmatic formations that play a crucial role in understanding the final stages of magmatic system evolution. They act as natural concentrators of rare and dispersed elements, serve as sources of strategically important minerals, and provide valuable insight into melt fractionation, degassing processes, and the tectono-magmatic evolution of the continental crust. Since pegmatites often form in post-metamorphic settings, they are also informative for reconstructing the late stages of regional geodynamic development.

In East Antarctica, pegmatites are widespread within ancient metamorphic complexes and have been the subject of multiple local-scale studies over recent decades. However, systematic and integrated research on these formations remains limited.

The Larsemann Hills oasis, located in the coastal part of Princess Elizabeth Land, represents a unique geological setting where metamorphic and magmatic rocks of various ages are exposed in a relatively small area, preserving evidence of multiple global tectono-thermal events. The presence of well-exposed pegmatite bodies, often retaining primary zoning, makes this area especially valuable for studying pegmatite formation processes in the context of deep continental crust evolution. Despite attracting research attention over the past thirty years, key questions regarding the formation conditions, timing, and internal classification of these pegmatites remain unresolved [1-3]. This study aims to address these gaps through a comprehensive investigation of the morphological, mineralogical-geochemical, and geophysical characteristics of specific pegmatite types. Special emphasis is placed on the detailed description of miarolitic and rare-metal pegmatites that have not previously been reported in this region.

During the 70th Russian Antarctic Expedition (2024-2025), a team from Saint Petersburg Mining University conducted integrated geological and geophysical surveys on the Broknes Peninsula (Larsemann Hills oasis, Princess Elizabeth Land, East Antarctica). The research focused on the Upper Proterozoic metamorphic complexes forming the peninsula, including mapping and mineralogical-geochemical sampling. Another component of the study involved examining fault structures, with detailed descriptions and photographic documentation aimed at producing a tectonic map of the area.

Geological setting

East Antarctica represents a cratonic region predominantly composed of Archean and Proterozoic metamorphic rocks [4, 5]. The geological evolution of the region is associated with several orogenic phases, the most significant of which occurred in the Late Archean, Early Proterozoic, and Late Riphean to Ediacaran, corresponding to the formation of the supercontinents Columbia, Rodinia, and Gondwana [6-8]. The most extensive rock exposures are found along the coastal belt of East Antarctica, where granulites, gneisses, and migmatites are widespread [9-11], along with relatively rare, younger intrusive bodies of various compositions, including pegmatites. These pegmatites formed during the late stages of granitoid magma crystallization in the Early Paleozoic within a collisional tectonic setting [12].

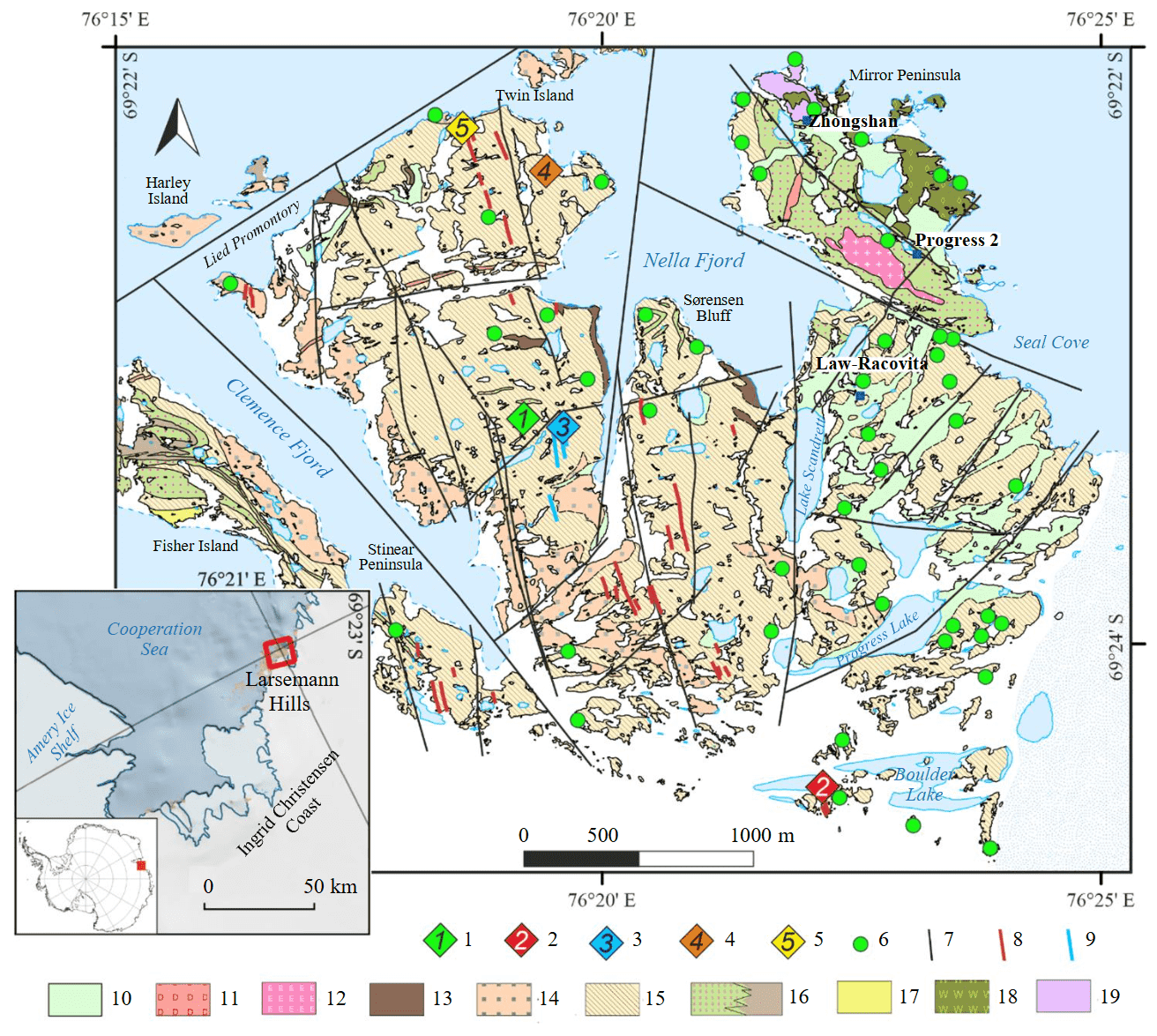

The geological structure of the Larsemann Hills oasis, located on the coast of Prydz Bay in East Antarctica, comprises both ortho- and paragneisses of amphibolite to granulite facies [13], forming a heterogeneous complex of metamorphic formations. The main units of the geological section in the study area include: mesoproterozoic Nella mafic granulites, Zhongshan leucogneisses, and Blundell orthogneisses; as well as neoproterosoic paragneisses of the Brattstrand sequence, which are subdivided into several subunits – Stüwe metapelites, Lake Ferris metapelites, Broknes paragneisses, Gentner metapsammites, and White Hill leucogneisses [14] (Fig.1).

The Nella mafic granulites are composed of ortho- and clinopyroxene, amphibole, plagioclase, and biotite, with minor amounts of quartz and magnetite. The mineral composition of the remaining rock complexes is predominantly represented by quartz and feldspar, with variable amounts of biotite, garnet, sillimanite, and cordierite. The protoliths of the orthogneisses are believed to have been mafic and felsic rocks dated to 940-1126 Ma [15]. The timing of protolith formation for the paragneisses remains a subject of debate. Some researchers attribute the age of sediment deposition to the Ediacaran period (600-575 Ma) [16-18] while others suggest a Cambrian age of around 515 Ma [19], while others argue that these processes occurred much earlier, during the Mesoproterozoic to Early Neoproterozoic (1100-970 Ma) [15, 20]. It is widely accepted among researchers that the region experienced two major high-temperature metamorphic events: the first occurred around 1000-900 Ma during the Grenvillian orogeny (D1), and the second took place around 580-510 Ma during the Pan-African orogeny (D2-4) [13, 20-22]. The latter event was associated with widespread anatexis, the emplacement of Cambrian granitoids of the Progress Complex, and the formation of a diverse array of pegmatite bodies differing in structural-tectonic setting and internal zoning – these pegmatites constitute the primary focus of the present study. Within the Larsemann Hills oasis, previous studies have identified two [1, 2], or in other interpretations, three [3] types of pegmatites associated with different stages of the Pan-African orogeny – D2-3 (578-531 Ma) [1, 23], D4 (526-510 Ma) [23], and post-D4 (circa 515 Ma) [3].

Fig.1. Location of the study area on the map of Antarctica and geological map of the Broknes Peninsula, Larsemann Hills oasis [14] (with authors’ additions)

Key outcrops 1-5: 1 – borosilicate pegmatite D2-3, 2 – rare-metal pegmatite D4, 3 – K-feldspar pegmatite D4', 4 – muscovite pegmatite post-D4, 5 – miarolitic pegmatite post-D4'; 6 – bodies of borosilicate pegmatites D2-3; 7 – faults; 8 – veins of rare-metal pegmatites D4; 9 – veins of K-feldspar pegmatites D4'; 10 – loose sediments (Q); 11 – Progress microgranite (ϵ1); 12 – Progress granite (ϵ1); paragneisses of the Brattstrand formation (R3) 13-16: 13 – White Hill leucogneiss, 14 – Gentner metapsammite, 15 – Broknes paragneiss, 16 – Lake Ferris / Stüwe metapelite; 17 – Blundell orthogneiss (R3); 18 – Zhongshan gneiss (R3); 19 – Nella mafic granulite (R3)

This study proposes an expanded classification of pegmatites, taking into account new field geological and geophysical data on their structural-tectonic position, zoning patterns, and mineral composition. The revised typology includes borosilicate D2-3 pegmatites, rare-metal D4 pegmatites, muscovite post-D4 pegmatites, as well as two newly identified types: K-feldspar D4' pegmatites and miarolitic rare-metal post-D4' pegmatites. In addition to these distinguishing features, the pegmatites differ in age, protolith composition, mineralogical-geochemical characteristics, and structural-textural attributes.

Methods

Comprehensive geological and geophysical fieldwork in the area of Progress Station included geological traverses, descriptions of key outcrops, magnetometry, and gamma spectrometric surveys. A total of 87 pegmatite occurrences were identified and described during the field campaign. Some pegmatite bodies were initially delineated through interpretation of aerial photographs obtained during the creation of orthophotomaps using a DJI Mavic Air 2 UAV (DJI, China). Additional pegmatite bodies were detected based on ground magnetic surveys conducted at a scale of 1:10,000 using a MiniMag Overhauser magnetometer (GeoDevice LLC, Russia). At key pegmatite outcrops, detailed investigations were carried out to assess geological structure, relationships with tectonically weakened zones, and internal zoning. Gamma spectrometric measurements were performed both on specific localities and along survey profiles using the MKCP-01 portable gamma spectrometer (NTC RADEK LLC, Russia), with exposure times ranging from 600 to 1800 s. Selected rock samples were promptly delivered to Saint Petersburg and analyzed at the Laboratory of the Institute of Precambrian Geology and Geochronology, RAS, using a SPECTROSCAN MAX-GVM X-ray fluorescence analyzer (SPEKTRON NPO LLC, Russia).

Results

The most representative pegmatite bodies of different types were described at key outcrops: borosilicate D2-3 (N 1), rare-metal D4 (N 2), K-feldspar D4' (N 3), muscovite-bearing post-D4 (N 4), and miarolitic post-D4' (N 5) (Fig.1).

The following section provides a detailed examination of the identified pegmatite types, including both newly described varieties and those previously mentioned in the literature [1-3, 23], but not previously studied within a unified context and remaining insufficiently characterized.

Borosilicate pegmatites D2-3

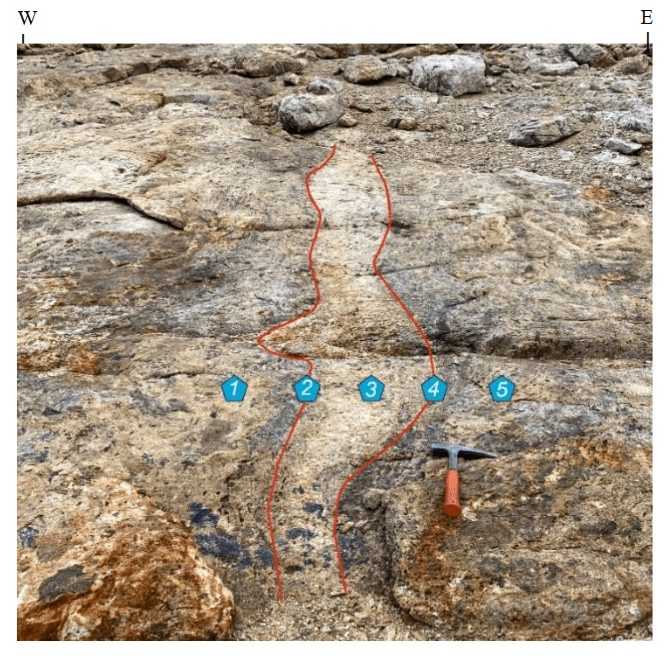

The earliest pegmatites in the study area are associated with the D2 and D3 deformation events, which occurred during the Pan-African orogeny [1], and are represented by borosilicate pegmatites of the D2-3 type. These pegmatites are believed to have formed as a result of melt differentiation during partial melting of borosilicate-rich paragneisses in the Early Paleozoic, between 578 and 531 Ma [1, 23]. During subsequent tectonic events, these formations underwent deformation [2]. D2-3 pegmatite bodies were observed at 48 locations, primarily within the Broknes subformation paragneisses, and less commonly within the Gentner metapsammites. Structurally, these rocks occur as subconcordant lenses and vein-like bodies aligned with the host metamorphic foliation, reaching lengths of several tens of meters and thicknesses of up to 1-2 m (Fig.2), the dip of which in most cases corresponds to the dip of the host rocks. Their contacts with host rocks are sharp and irregular. These pegmatites lack well-developed internal zoning. The main rock-forming minerals include K-feldspar, plagioclase, gray to milky-white quartz, and coarse-flaky biotite. A distinctive feature of this type is the high content of rare borosilicate minerals, such as dumortierite, prismatine, grandidierite, boralsilite, and tourmaline (Table 1) [2, 3, 24]. Boron mineralization is particularly widespread in the western part of the Larsemann Hills oasis, on the Stornes Peninsula, which led to the establishment of a specially protected natural area within this territory [25].

Fig.2. Vein body of borosilicate pegmatite D2–3 (key outcrop N 1) within host paragneisses of the Broknes subformation (hammer length for scale – 30 cm)

1-5 – points of gamma spectrometry observations

Table 1

Comparative geological and mineralogical characteristics of pegmatite types in the Larsemann Hills oasis

|

Characteristics |

Pegmatite type |

||||

|

Borosilicate pegmatites D2-3 |

Rare-metal pegmatites D4 |

K-feldspar pegmatitesD4' |

Muscovite-bearing pegmatitespost-D4 |

Miarolitic pegmatitespost-D4' |

|

|

Age, Ma |

578-531 [1, 23] |

526-510 [23] |

521-517 [1] |

515? [3] |

? |

|

Distribution |

Widespread |

Western and central parts of the Broknes Peninsula |

Westernand central parts of the Broknes Peninsula |

Northwestern part of the BroknesPeninsula and nearby islands |

Northwestern part of the Broknes Peninsula |

|

Host rock |

Brattstrand paragneiss (Neoproterozoic) |

||||

|

Mode of occurrence |

Lenses [26] / vein bodies |

Veins |

Veins |

Veins / lenses |

Lenses |

|

Zoning |

Absent |

Well-defined |

Well-defined |

Well-defined |

Well-defined |

|

Formation temperature, °C |

750-800 [3] |

>800 [3] |

550-650 [27] |

490-580 [3] |

350-500? [28-30] |

|

Pressure, GPa |

0.4-0.7 [3] |

>0.4-0.7 [3] |

0.15-0.45 [27] |

0.35-0.2 [3] |

>0.25? [28] |

|

Effective specific activity Aₑff, Bq/kg |

56.70-59.00 |

61.50-103.00 |

17.40-206.00 |

45.90-67.60 |

52.20-910.00 |

|

Dominant feldspar |

K-feldspar + plagioclase |

K-feldspar + plagioclase |

K-feldspar |

K-feldspar |

K-feldspar |

|

Dominant mica type |

Biotite |

Biotite |

Biotite |

Muscovite |

Biotite |

|

Quartz SiO2 |

Gray |

White |

Gray |

Light gray |

Gray to smoky |

|

Sillimanite Al2SiO5 |

XXX |

XXX |

|

|

|

|

Andalusite Al2SiO5 |

(*) [2] |

|

|

(*) [3] |

XXХ? |

|

Beryl Al2Be3[Si6O18] |

|

? |

|

XXX [3] |

|

|

Tourmaline NaR3Al6(OH)1+3|(BO3)3[Si6O18] |

X / ХXХ |

XXХ |

XXX |

X [3] |

|

|

Garnet (almandine) Fe2+3Al2[SiO4]3 |

XXX |

XXX |

XXX |

|

X |

|

Cordierite Al3Mg2[AlSi5O18] |

XXX |

|

|

|

|

|

Orthopyroxene |

|

X [26] |

|

|

|

|

Grandidierite (Mg, Fe)Al3[O|BO4|SiO4] |

X / XXX [2, 3] |

|

|

|

|

|

Boralsilite Al16B6Si2O37 |

ХXX [3, 24] |

Х [3] |

|

|

|

|

Prismatine (Mg, Na)2Mg(Al, Fe, Mg)6 [Si2O7][(Al, Si)2(Si, B)O10]O4(O, OH) |

XXX |

|

|

|

|

|

Dumortierite Al4[(Al4BSi3)O19OH] |

(*) [3] |

Х [3] |

|

|

|

|

VerdingiteAl8[(Mg, Fe)2Al4(Al, Fe)2Si4(B, Al)4]O37 |

X [24] |

|

|

|

|

|

Apatite Ca5[(PO4)3|( F, Cl, OH)] |

X [24] |

Х |

? |

|

XXХ |

|

Monazite (Ce, La, Y)[PO4] |

X [3] |

X [26] |

Х |

|

X |

|

Xenotime YPO4 |

X [24] |

X [24] |

Х |

|

X |

|

Zircon (Zr, Hf, Th, U, TR, Ca, Na) [(Si, Al, P, S) (Ti, Zr, Th)3O7] |

X [24] |

X [24] |

X [1] |

|

X |

|

Uranium-bearing mineral |

|

|

|

|

ХХХ |

|

Chrysoberyl Al2BeO4 |

|

XXX |

|

|

|

|

Magnetite Fe2+Fe3+2O4 |

XXX |

ХXX |

ХXX |

|

X |

|

Spinel MgAl2O4 |

|

XХX [26] |

|

|

|

|

Ilmenite FeTiO2 |

|

X [26] |

|

|

|

|

Rutile TiO2 |

X [24] |

Х [23] |

|

|

X |

|

Corundum Al2O3 |

|

(*) [26] |

|

|

|

|

Diaspore AlOOH |

|

(*) [26] |

|

|

|

|

Pyrite FeS2 |

X [24] |

|

|

|

XXX |

Note.XXX – mineral occurs in significant amounts; X – mineral occurs as small grains in thin sections or concentrates; (*) – secondary mineral; ? – requires further clarification. Field identifications were made visually or using X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analysis.

According to gamma spectrometry data, the identified borosilicate D2-3 pegmatites show isotope concentrations of potassium, uranium, and thorium that are nearly indistinguishable from those of the host paragneisses (Table 2).

Table 2

Average concentrations of natural radionuclides and effective activity of borosilicate D2-3 pegmatite and host paragneisses of the Broknes subformation based on gamma spectrometry data (key outcrop N 1)

|

Zone |

Concentration |

||||

|

40K, % |

U (226Ra), ppm |

232Th, ppm |

Aeff, Bq/kg |

Th/U |

|

|

Host paragneisses |

5.34 |

1.50 |

41.82 |

56.70 |

27.84 |

|

Contact between host paragneisses and pegmatites |

7.31 |

1.36 |

42.10 |

57.10 |

31.05 |

|

Central part of the pegmatite body |

7.39 |

1.20 |

43.62 |

59.00 |

36.35 |

Rare-metal pegmatites D4

The emplacement of the younger rare-metal D4 pegmatites is also linked to the Pan-African orogeny [1]. They are believed to have formed through melt differentiation derived from multiple sources during anatexis processes [3] between 526 and 510 Ma [23]. D4 pegmatite bodies were recorded at 35 observation points, mainly within the Broknes subformation paragneisses. Structurally, these pegmatites form extensive (up to 150-200 m long), subvertical, cross-cutting veins up to 1 m thick, trending north-northwest and controlled by submeridional fault zones. This pegmatite type is most prominently developed in the western part of the Broknes Peninsula (see Fig.1). They are periodically observed to cross-cut the D2-3 pegmatites. Frequently, these bodies are affected by later linear deformations, represented by mylonite zones up to 20 cm thick and extensive fractures. The main rock-forming minerals of these pegmatites include orange to pink and flesh-red potassium feldspar, plagioclase, white quartz, and coarse-flaky biotite. Accessory minerals comprise magnetite, spinel, garnet (almandine), sillimanite, tourmaline, and chrysoberyl – which is described here for the first time in the Larsemann Hills oasis and, more broadly, in Princess Elizabeth Land – forming relatively large (up to 2-3 cm) characteristic twins and triplets. Interestingly, similar abyssal pegmatites described in other parts of the world never exhibit simultaneous development of boron and beryllium mineralization [31].

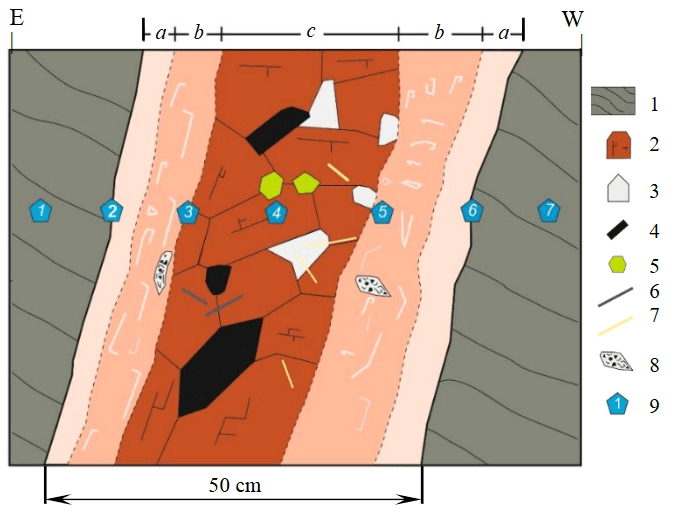

All veins of this type exhibit distinct zonation (Fig.3) with gradual contacts between zones (from margins to center, illustrated by a K-feldspar pegmatite from key outcrop N 2):

a – the marginal zones consist of fine- to medium-grained feldspar-quartz aggregates. Clusters of magnetite are observed in the western, typically footwall, marginal zones;

b – the graphic zone is not ubiquitous and is characterized by large feldspar aggregates with sparse quartz ichthyoglypts and rare small (1-2 cm) graphic intergrowths of quartz and tourmaline;

c – the blocky zone comprises large idiomorphic potassium feldspar crystals, often accompanied by coarse-flaky biotite and much less commonly by quartz. In some rare-metal veins within this zone, well-formed twins and triplets of chrysoberyl up to several centimeters in size, as well as sillimanite and tourmaline crystals, have been documented.

Fig.3. Schematic cross-sectional sketch of the zonal structure of a rare-metal pegmatite vein D4 (key outcrop N 2).

Zones: а – marginal; b – graphic; с – blocky 1 – Broknes paragneiss; 2 – potassium feldspar; 3 – quartz; 4 – biotite; 5 – chrysoberyl; 6 – tourmaline; 7 – sillimanite; 8 – graphic intergrowths of quartz and tourmaline; 9 – points of gamma spectrometry observation

Rare-metal D4 pegmatites show slightly elevated concentrations of natural radionuclides and effective activity compared to the host paragneisses (Table 3).

Table 3

Average concentrations of natural radionuclides and effective activity of rare-metal D4 pegmatite and host paragneisses of the Broknes subformation based on gamma spectrometry data (key outcrop N 2)

|

Zone |

Concentration |

||||

|

40K, % |

U (226Ra), ppm |

232Th, ppm |

Aeff, Bq/kg |

Th/U |

|

|

Host paragneisses |

3.05 |

1.92 |

45.30 |

61.50 |

23.64 |

|

Contact between host paragneisses and pegmatites |

3.68 |

3.24 |

53.87 |

74.10 |

16.61 |

|

Blocky zone of the pegmatite |

5.25 |

4.38 |

75.03 |

103.00 |

17.13 |

K-feldspar pegmatites D4' are significantly less common in the study area, having been identified at only three observation points in the western part of the Broknes Peninsula. U-Pb isotopic dating indicates their age to be 517-521 Ma [1]. Structurally and in terms of their association with fault zones, these pegmatites do not differ from the previously described rare-metal D4 pegmatites and have not been distinguished as a separate group by other researchers. However, they are reliably distinguished by their mineral composition – they consist almost entirely of large (up to 30-40 cm) white elongated orthoclase crystals, often displaying macroscopic twins. Subordinate minerals include gray quartz, typically found in the selvages of veins or as chains of small (up to 1 cm) quartz aggregates forming in the blocky zone at the boundaries of orthoclase crystals, and coarse-flaky idiomorphic biotite. Accessory minerals include magnetite and garnet (almandine) crystals. These pegmatites also exhibit zonal structure (Fig.4).

Fig.4. Schematic cross-sectional sketch of the structure of a K-feldspar pegmatite vein D4' (key outcrop N 3).

Zones: а – marginal (Ort-Bt-Q-(Mag); b – blocky (Ort-Q); c – mylonitization (Pl-Bt)

Ort – orthoclase; Bt – biotite; Q – quartz; Mag – magnetite; 1 – paragneisses; 2 – orthoclase; 3 – quartz; 4 – biotite; 5 – garnet; 6 – points of gamma spectrometry observations

According to gamma spectrometry data, K-feldspar pegmatites D4' also differ from rare-metal pegmatites by elevated thorium isotope concentrations, higher effective activity values, and increased thorium-to-uranium ratios (Table 4).

Table 4

Average concentrations of natural radionuclides and effective activity of K-feldspar D4' pegmatite and host paragneisses of the Broknes subformation based on gamma spectrometry data (key outcrop N 3)

|

Zone |

Concentration |

||||

|

40K, % |

U (226Ra), ppm |

232Th, ppm |

Aeff, Bq/kg |

Th/U |

|

|

Host paragneisses |

3.58 |

1.13 |

12.20 |

17.40 |

10.77 |

|

Contact between host paragneisses and pegmatites |

6.41 |

2.86 |

79.32 |

107.00 |

27.73 |

|

Blocky zone of the pegmatite |

8.00 |

4.65 |

152.80 |

206.00 |

32.83 |

Muscovite pegmatites post-D4

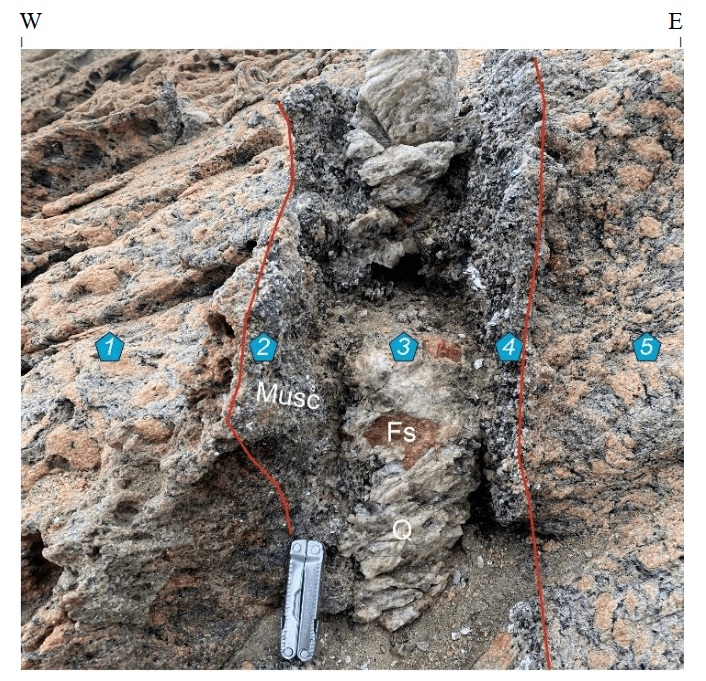

The younger pegmatite formations associated with the Pan-African orogeny are distinguished by some researchers as a separate group [3]. It is suggested that they formed contemporaneously with the Progress granites around 515 Ma from a common protolith [22]. These pegmatites have a very limited distribution in the study area, restricted to the northwest part of the Broknes Peninsula; post-D4 pegmatite bodies were identified at only two observation points. They occur as cross-cutting and sub-concordant veins and lenses trending north-northwest, with lengths up to 100-150 m and thicknesses up to 30 cm, often displaying clear zonal structure (Fig.5). The main rock-forming minerals include pale orange potassium feldspar, coarse-flaky idiomorphic muscovite, and light gray quartz.

Fig.5. Vein of muscovite post-D4 pegmatite in paragneisses of the Broknes subformation (key outcrop N 4). Knife length 10 cm

Q – quartz; Musc – muscovite; Fs – potassium feldspar

Similar pegmatites described in [3], occurring on some northern islands of the oasis, may also contain beryl. The presence of large idiomorphic muscovite crystals, which are absent in other pegmatite types, justifies distinguishing these pegmatites as a separate group. This fact, along with the possible presence of beryl, suggests that the emplacement of post-D4 muscovite pegmatites occurred at lower temperatures and likely corresponds to a younger age. Gamma spectrometry data indicate that these rocks are relatively depleted in radioactive elements compared to the rare-metal, K-feldspar-rich, and miarolitic pegmatites (Table 5).

Table 5

Average concentrations of natural radionuclides and effective activity of muscovite post-D4 pegmatite and host paragneisses of the Broknes subformation based on gamma spectrometry data (key outcrop N 4)

|

Zone |

Concentration |

||||

|

40K, % |

U (226Ra), ppm |

232Th, ppm |

Aeff, Bq/kg |

Th/U |

|

|

Host paragneisses |

5.25 |

2.49 |

32.80 |

45.90 |

13.18 |

|

Contact between host paragneisses and pegmatites |

4.09 |

2.04 |

34.78 |

48.00 |

17.07 |

|

Central zone of the pegmatite |

5.11 |

3.71 |

48.47 |

67.60 |

13.05 |

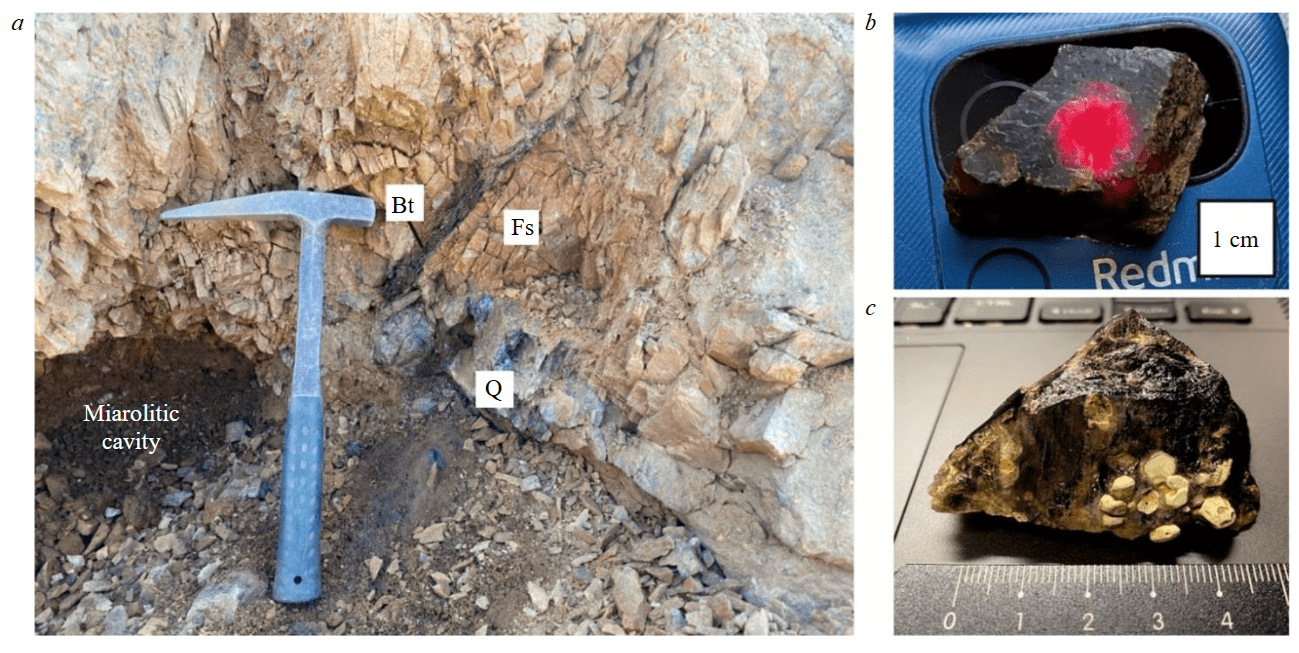

Miarolitic pegmatites post-D4'

Miarolitic pegmatites represent some of the most intriguing geological formations. Currently, there is no publicly available information on the discovery of miarolitic pegmatite bodies in Antarctica. Such formations are rare in ancient high-grade metamorphic terrains, making the discovery of a miarolitic pegmatite among the metamorphics of the Larsemann Hills a significant finding. The miarolitic pegmatite was initially identified from numerous fragments of quartz crystals exhibiting euhedral growth faces, found within deluvial deposits in Upper Proterozoic migmatized paragneisses in the western part of the Broknes Peninsula. Continued exploration led to the discovery of a relatively large (1×0.5×1 m3) zoned body, lying horizontally and subconcordantly within the Broknes paragneisses. The presence of asymmetric zoning, cavities lined with euhedral crystals (Fig.6), and a marked difference in natural isotope concentrations and their activity distinguish this pegmatite as a separate group.

Fig.6. Structure of the miarolitic post-D4′ pegmatite (a) and selected minerals found within it: apatite illuminated by a flashlight (b), and smoky quartz with inclusions of a strongly weathered unknown mineral (c)

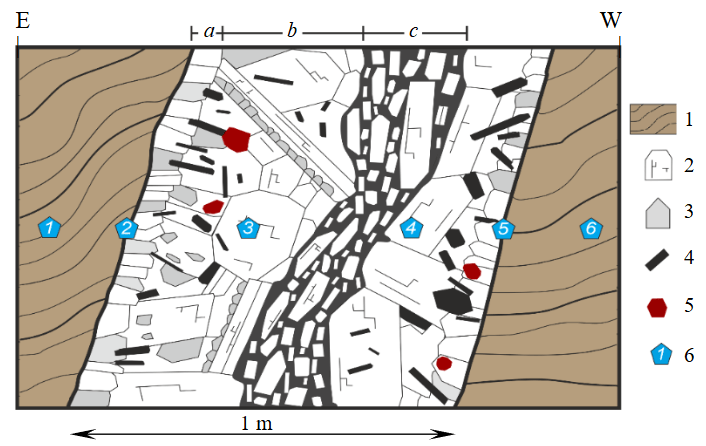

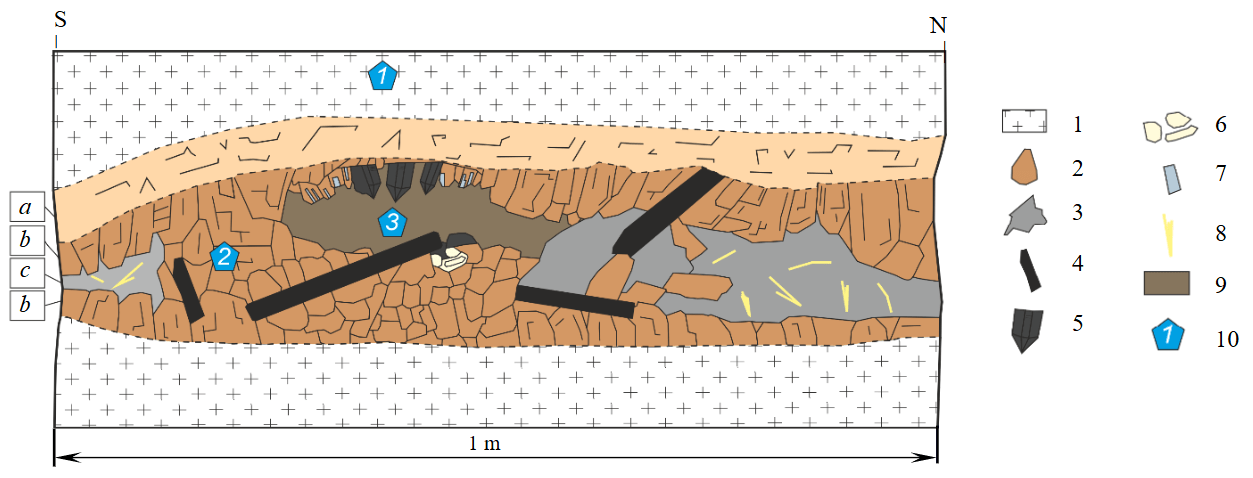

The structure of the described miarolitic pegmatite comprises several gradually transitioning zones (Fig.7):

a – the graphic zone, characterized by not always clearly defined intergrowths of potassium feldspar and quartz;

b – the blocky zone, consisting of large aggregates of potassium feldspar with occasional large biotite crystals up to 30 cm in size (Fig.6, a). This zone contains numerous miarolitic cavities ranging from 15 to 30 cm in size, lined with crystals of smoky quartz (Fig.6, c), potassium feldspar, bluish iridescent plagioclase, rutile (as inclusions in quartz), ilmenite, brownish-red apatite (Fig.6, b) with inclusions of yttrium-bearing monazite, as well as dark radioactive cryptocrystalline phases and several as yet unidentified weathered minerals. The cavities are filled with a loose clayey material containing abundant small golden crystals of xenotime and monazite;

c – the core, composed of massive gray quartz aggregates with numerous, often curved, greenish-yellow matte crystals – likely andalusite – up to 7-10 cm long, along with rare pyrite inclusions.

Fig.7. Schematic cross-sectional sketch of the miarolitic pegmatite structure (key outcrop N 5)

Zones: a – graphic; b – blocky; c – quartz core

1 – Broknes paragneisses; 2 – potassium feldspar; 3 – quartz core; 4 – biotite; 5 – quartz crystals; 6 – ilmenite (?); 7 – plagioclase; 8 – andalusite (?); 9 – clay from miarolitic cavity; 10 – points of gamma spectrometry observations

Gamma spectrometry measurements conducted across the zoning profile of the pegmatite body show some of the highest concentrations of natural radionuclides and effective activity values recorded in the study area (Table 6).

Table 6

Average concentrations of natural radionuclides and effective activity in miarolitic post-D4′ pegmatite and host migmatized metamorphics based on gamma spectrometry data (key outcrop N 5)

|

Zone |

Concentration |

||||

|

40K, % |

U (226Ra), ppm |

232Th, ppm |

Aeff, Bq/kg |

Th/U |

|

|

Migmatized metamorphic host rocks |

5.36 |

0.70 |

39.00 |

52.20 |

55.47 |

|

Block zone of the pegmatite body |

10.89 |

21.71 |

592.00 |

798.00 |

27.27 |

|

Miarolitic cavity |

7.21 |

39.85 |

663.70 |

910.00 |

16.66 |

This pegmatite body, together with the host migmatized paragneisses, is also distinguished by a negative linear magnetic anomaly recorded during the surveys, extending approximately 150 m in length and up to 30 m in width.

Discussion

Several types of pegmatites associated with Pan-African orogenic events (circa 580-510 Ma) are distinguished within the Larsemann Hills oasis. Their formation corresponds to the global peak of tectono-magmatic activity in the Early Paleozoic, which was manifested over extensive areas worldwide during the collisional orogeny and the assembly of supercontinents [32].

Recently, several attempts have been made to systematize information on the pegmatites of the Larsemann Hills oasis and to clarify the conditions and sequence of their formation. One of the main challenges in these studies is that absolute dating of different pegmatite types is not always indicative, as the results often overlap or differ only within the margin of analytical uncertainty. For K-feldspar-rich, muscovite, and miarolitic pegmatites, very few reliable data exist on their absolute ages and thermobaric formation conditions, or such data are completely lacking. From this perspective, primary field observations on the relationships between these pegmatite types are of great value.

It is suggested that the emplacement of the earliest pegmatites is associated with the deformation events D2 and D3, which led to the formation of extensional zones trending submeridionally [1]. The D2-3 pegmatites are characterized by abundant boron mineralization and contain very rare minerals such as grandidierite and prismatine, as well as newly described minerals previously known only from meteorites, like boralsilite [3, 24, 25]. Based on PT stability conditions of boralsilite, it is proposed that the D2-3 pegmatites formed at temperatures of 750-800 °C and pressures of 0.4-0.7 GPa (see Table 1) during partial melting of boron-rich paragneisses [3]. Absolute age determinations of these formations, obtained from monazite and zircon by various authors, are broadly consistent – 578-531 Ma [23] and 562-534 Ma [1] – corresponding to the timing of the tectono-magmatic event that triggered partial melting of the host rocks. It is considered that during subsequent processes these bodies were folded, mostly concordantly with the host rocks, and in some cases disrupted by brittle dislocations along which later pegmatites were emplaced.

Field observations indicate that D2-3 pegmatite formations are widespread throughout the study area, occurring as lenses and short veins up to a few meters thick with irregular contacts, generally concordant with the host rocks. On the Broknes Peninsula, boron mineralization is almost absent in D2-3 pegmatites; the largest occurrences are concentrated in the western part of the oasis, on the Stornes Peninsula. Gamma spectrometry data show that D2-3 pegmatites do not exhibit significant differences in radionuclide content compared to the host Broknes paragneisses and Gentner metapsammites, while they are characterized by lower values relative to the rare-metal D4, K-feldspar D4′, and miarolitic post-D4′ pegmatites. This may be related both to the high-temperature crystallization conditions of these pegmatites and to enhanced Th and U mobility during subsequent metamorphic processes [33].

Subsequently, late deformation processes D4 [1] were superimposed on the areas that experienced extension during the D3 event, resulting in further extension and emplacement of D4 pegmatites within weakened zones. Rare boralsilite inclusions have also been found in these rocks, suggesting that D4 pegmatites formed under thermobaric conditions similar to those of the D2-3 pegmatites [3]. Monazite dating indicates that the D4 pegmatites were formed between 526 and 510 Ma [23] as a result of partial melting of a substrate derived from multiple sources [3]. Field observations show that D4 pegmatites are predominantly localized in the western and central parts of the Broknes Peninsula, within a zone approximately 5 km long and 2 km wide, corresponding to submeridional fault zones identified during geological traverses and previous studies. Gamma spectrometry data indicate that rare-metal D4 pegmatites have lower concentrations of natural radionuclides compared to K-feldspar D4' and miarolitic pegmatites, but exhibit elevated values relative to D2-3 and muscovite post-D4 pegmatites. This is likely related to the high-temperature and high-pressure crystallization conditions of these pegmatites, where Th and U remained largely in the melt. Of particular interest is the presence of a well-developed high-temperature mineral assemblage – potassium feldspar, sillimanite, and chrysoberyl – in these formations. According to numerous studies [34-36], chrysoberyls in pegmatites generally form on pre-existing beryl crystals. However, the absence of relic primary beryllium minerals and the high degree of idiomorphism of chrysoberyl crystals observed by the authors in D4 pegmatites suggest its primary origin. Moreover, the presence of chryso-beryl may indicate local enrichment of the melt in alumina derived from the host rocks [37, 38]. Beryllium could have been mobilized from metamorphic beryllium minerals (e.g., sapphirine Mg2.73Fe1.00Al1.14Be0.12B0.01Si2.4О20), as described in the granite pegmatites of the Napier Complex, Antarctica [31]. This evidence supports a higher-temperature nature of formation for the rare-metal D4 pegmatites [27, 31, 38].

Rare K-feldspar pegmatites D4', which occur locally within the zone of rare-metal D4 pegmatites and do not differ from them in structural position, are not distinguished as a separate type by other researchers. Nevertheless, based on their mineral composition – primarily the predominance of large (30-40 cm) potassium feldspar crystals – it can be inferred that these pegmatites formed later and at lower temperatures than the rare-metal D4 pegmatites. This conclusion is supported by zircon dating results from similar lightly colored pegmatites, indicating an age of formation between 521 and 517 Ma [1]. K-feldspar pegmatites typically crystallize at temperatures ranging from 550 to 650 °C [39]. Such conditions are characteristic of the late magmatic and pneumatolytic-hydrothermal stages of mineral formation, when residual volatile-rich fluids crystallize in fractures within the host rocks. Furthermore, gamma spectrometry data show that K-feldspar D4' pegmatites have higher radionuclide concentrations than borosilicate D2-3, rare-metal D4, and muscovite post-D4 pegmatites. This can be explained by the tendency of potassium feldspar to retain radionuclides within its structure, and the stated temperatures promote the accumulation of thorium and uranium in certain minerals [40].

Another, later type of pegmatite distinguished only in studies [3, 23] are the muscovite post-D4 pegmatites. It is assumed that this type is the most distant from the melt source and formed at lower temperatures (490-580 °C) and pressures below 0.4 GPa [3]. Currently, no publicly available data exist on the absolute age of these bodies; however, study [3] demonstrates that isotopic characteristics of muscovite pegmatites are similar to those of the Cambrian Progress granites (see Fig.1), suggesting their formation age to be approximately 515 Ma [41]. These pegmatites have a very limited distribution in the study area. Geographically, they are localized in the northern part of the weakened zone, intruded by rare-metal and K-feldspar D4 pegmatites. Gamma spectrometry observations indicate that these formations have some of the lowest recorded concentrations of natural isotopes among the pegmatites – muscovite and quartz weakly accumulate uranium and thorium, and radionuclides may migrate with later hydrothermal fluids, reducing their concentration in the rock. It is likely that muscovite pegmatites are associated with the final stage of anatectic processes.

Of particular interest is the discovery of miarolitic pegmatites within the Larsemann Hills oasis. Such formations have not been previously described in the study area, and this finding warrants further detailed and comprehensive investigation. The described body significantly differs from all other studied pegmatites in terms of structure, mineral composition, and gamma spectrometry results, which show a sharp increase in natural isotope concentrations and their activity. Moreover, unlike all other pegmatites, it is distinctly distinguished by magnetic survey data, exhibiting characteristics similar to those described in [42-44]. Based on initial field data, it is hypothesized that the formation of this body occurred during the latest stages of the pegmatitic process at the lowest temperatures among the considered pegmatite types, likely around 350-500 °C [28, 45], from an aluminosilicate melt enriched in dissolved water and volatile components (e.g., phosphorus). According to precursor calculations, the temperatures of the final retrograde stages of the Pan-African metamorphic event ranged from 550 to 650 °C [21]. High concentrations of volatile components and slow crystallization led to the formation of minerals with well-developed crystallographic forms and elevated natural radionuclide contents in this body. The absence of sharp boundaries with the host rocks and its distinctive mineral paragenesis allow it to be initially classified as a rare-element abyssal pegmatite associated with S-type granitoids [46, 47].

According to current understanding, all the described pegmatite types belong to the abyssal pegmatites of the LCT family, formed as a result of partial melting of one or more protoliths. High-temperature varieties, such as borosilicate and rare-metal pegmatites, likely crystallized under granulite-facies metamorphic conditions associated with the Pan-African orogeny. Other pegmatite types formed at lower temperatures during subsequent stages of geodynamic evolution [23].

Conclusion

Based on the data obtained from comprehensive geological and geophysical studies and in agreement with previous research, five distinct types of pegmatites are confidently distinguished within the Larsemann Hills oasis: borosilicate D2-3, rare-metal D4, K-feldspar D4′, muscovite post-D4, and miarolitic post-D4′ pegmatites. These pegmatites predominantly occur within the Upper Proterozoic paragneisses of the Broknes subformation. All are associated with different stages of the Pan-African orogeny and correspond to the global Early Paleozoic peak of pegmatite formation. Field measurements indicate that all pegmatite types are well differentiated by the morphology of pegmatite bodies, zoning patterns, mineral composition, gamma spectrometry data, and in some cases, magnetic surveys. For example, D2-3 pegmatites commonly form concordant vein-like and lens-shaped bodies, characterized by rare borosilicate mineralization. Cross-cutting rare-metal D4 pegmatites, K-feldspar D4′ pegmatites, and muscovite post-D4 pegmatites are localized within a zone of maximum development of parallel north-northwest faults, interpreted as a weakened structural zone healed by the described pegmatite formations. Within this same zone, the miarolitic pegmatite is also found, whose nature and timing of formation raise the most questions. Maximum radionuclide concentrations are observed in K-feldspar and miarolitic pegmatites, somewhat lower in rare-metal pegmatites, and the lowest isotope contents are recorded in borosilicate and muscovite pegmatites.

The information collected by the authors during the field season, along with the discovery of new, previously undescribed geological bodies, expands the understanding not only of the history and characteristics of pegmatite formation in the Larsemann Hills oasis but also of the geodynamic evolution stages of the region and adjacent areas, such as the Indian craton and other fragments of the former Gondwana. Future work will focus on detailed studies of the identified pegmatite types using precise geochemical analyses of both primary and accessory minerals, refinement of the thermobaric conditions of their crystallization, and determination of their absolute ages and formation sequence.

References

- Shi Zong, Yingchun Cui, Liudong Ren et al. Geochemical Characteristics, Zircon U-Pb Ages and Lu-Hf Isotopes of Pan-African Pegmatites from the Larsemann Hills, Prydz Bay, East Antarctica and Their Tectonic Implications. Minerals. 2024. Vol. 14. Iss. 1. N 55. DOI: 10.3390/min14010055

- Wadoski E.R., Grew E.S., Yates M.G. Compositional evolution of tourmaline-supergroup minerals from granitic pegmatites in the Larsemann Hills, East Antarctica. The Canadian Mineralogist. 2011. Vol. 49. N 1, p. 381-405. DOI: 10.3749/canmin.49.1.381

- Maas R., Grew E.S., Carson C.J. Isotopic constraints (Pb, Rb-Sr, Sm-Nd) on the sources of early Cambrian Pegmatites with boron and beryllium minerals in the Larsemann hills, Prydz Bay, Antarctica. The Canadian Mineralogist. 2015. Vol. 53. N 2, p. 249-272. DOI: 10.3749/canmin.1400081

- Leitchenkov G.L., Grikurov G.E. The Tectonic Structure of the Antarctic. Geotectonics. 2023. Vol. 57. Suppl. 1, p. S28-S33. DOI: 10.1134/S0016852123070087

- Gorelik G.D., Egorov A.S., Shuklin I.A., Ushakov D.E. Substantiation of optimal range of geophysical surveys to study deep structure of the Lake Vostok area. Gornyi zhurnal. 2024. N 9, p. 56-61 (in Russian). DOI: 10.17580/gzh.2024.09.09

- Satish-Kumar M., Motoyoshi Y., Osanai Y. et al. Geodynamic Evolution of East Antarctica: A Key to East–West Gondwana Connection. London: The Geological Society, 2008. Geological Society Special Publication N 308, p. 464.

- Grikurov G.E., Mikhalskii E.V. Tectonic structure and evolution of East Antarctica in the light of knowledge about supercontinents. Russian Journal of Earth Sciences. 2002. Vol. 4. N 4, p. 247-257. DOI: 10.2205/2002ES000099

- Abdrakhmanov I.A., Gulbin Yu.L., Gembitskaya I.M. Assemblage of Fe–Mg–Al–Ti–Zn Oxides in Granulites of the Bunger Hills, East Antarctica: Evidence of Ultrahigh-Temperature Metamorphism. Geology of Ore Deposits. 2022. Vol. 64. N 8, p. 519-549. DOI: 10.1134/S1075701522080025

- Sadiq M., Bhandari A., Arora D. et al. Late Neoproterozoic metamorphic evolution of Larsemann Hills, East Antarctica: Insights from pseudosection modelling and monazite–zircon geochronology of Easther Island porphyroblastic gneiss. Journal of Earth System Science. 2024. Vol. 133. Iss. 4. N 238. DOI: 10.1007/s12040-024-02434-9

- Gulbin Yu.L., Abdrakhmanov I.A., Gembitskaya I.M., Vasiliev E.A. Oriented Microinclusions of Al–Fe–Mg–Ti Oxides in Quartz from Metapelitic Granulites of the Bunger Hills, East Antarctica. Geology of Ore Deposits. 2023. Vol. 65. N 7, p. 656-668. DOI: 10.1134/S1075701523070048

- Mikhalsky E.V., Belyatsky B.V., Presnyakov S.L. et al. The geological composition of the hidden Wilhelm II Land in East Antarctica: SHRIMP zircon, Nd isotopic and geochemical studies with implications for Proterozoic supercontinent reconstructions. Precambrian Research. 2015. Vol. 258, p. 171-185. DOI: 10.1016/j.precamres.2014.12.011

- Abdrakhmanov I.A., Gulbin Y.L., Skublov S.G., Galankina O.L. Mineralogical Constraints on the Pressure–Temperature Evolution of Granulites in the Bunger Hills, East Antarctica. Minerals. 2024. Vol. 14. Iss. 5. N 488. DOI: 10.3390/min14050488

- Carson C.J., Dirks P.G.H.M., Hand M. et al. Compressional and extensional tectonics in low-medium pressure granulites from the Larsemann Hills, East Antarctica. Geological Magazine. 1995. Vol. 132. Iss. 2, p. 151-170. DOI: 10.1017/S0016756800011729

- Geology of the Larsemann Hills. Princess Elizabeth Land. Antarctica. 1:25 000 scale. First Edition. Canberra: Geoscience Australia, 2007.

- Grew E.S., Carson C.J., Christy A.G. et al. New constraints from U–Pb, Lu–Hf and Sm–Nd isotopic data on the timing of sedimentation and felsic magmatism in the Larsemann Hills, Prydz Bay, East Antarctica. Precambrian Research. 2012. Vol. 206-207, p. 87-108. DOI: 10.1016/j.precamres.2012.02.016

- Glazunov V.V., Efimova N.N., Zelikman D.I., Bukatov A.A. Zones Localization of Hazardous Geological Processes Habit of the Coastal Cliff According to 3D Seismotomography Sounding Data. Russian Journal of Earth Sciences. 2025. Vol. 25. N 1. N ES1001 (in Russian). DOI: 10.2205/2025es000993

- Kelsey D.E., Hand M., Clark C., Wilson C.J.L. On the application of in situ monazite chemical geochronology to constraining P–T–t histories in high-temperature (>850 °C) polymetamorphic granulites from Prydz Bay, East Antarctica. Journal of the Geological Society. 2007. Vol. 164. N 3, p. 667-683. DOI: 10.1144/0016-76492006-013

- Kelsey D.E., Wade B.P., Collins A.S. et al. Discovery of a Neoproterozoic basin in the Prydz belt in East Antarctica and its implications for Gondwana assembly and ultrahigh temperature metamorphism. Precambrian Research. 2008. Vol. 161. Iss. 3-4, p. 355-388. DOI: 10.1016/j.precamres.2007.09.003

- Hensen B.J., Zhou B. A Pan‐African granulite facies metamorphic episode in Prydz Bay, Antarctica: Evidence from Sm‐Nd garnet dating. Australian Journal of Earth Sciences. 1995. Vol. 42. Iss. 3, p. 249-258. DOI: 10.1080/08120099508728199

- Grew E.S., Carson C.J., Christy A.G., Boger S.D. Boron- and phosphate-rich rocks in the Larsemann Hills, Prydz Bay, East Antarctica: tectonic implications. Antarctica and Supercontinent Evolution. London: The Geological Society, 2013. Vol. 383, p. 73-94. DOI: 10.1144/SP383.8

- Fitzsimons I.C.W., Harley S.L. Geological relationships in high‐grade gneiss of the Brattstrand Bluffs coastline, Prydz Bay, East Antarctica. Australian Journal of Earth Sciences. 1991. Vol. 38. Iss. 5, p. 497-519. DOI: 10.1080/08120099108727987

- Yanbin Wang, Dunyi Liu, Sun-Lin Chung et al. SHRIMP Zircon Age Constraints From the Larsemann Hills Region, Prydz Bay, for a Late Mesoproterozoic to Early Neoproterozoic Tectono-Thermal Event in East Antarctica. American Journal of Science. 2008. Vol. 308. Iss. 4, p. 573-617. DOI: 10.2475/04.2008.07

- Spreitzer S.K. In Situ Dating of Multiple Events in Granulite-Facies Rocks of the Larsemann Hills, Prydz Bay, East Antarctica Using Electron Microprobe Analysis of Monazite: A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science (in Earth Science and Climate Sciences). USA, Main, 2017. N 2762, p. 347.

- Grew E.S., McGee J.J., Yates M.G. et al. Boralsilite (Al16B6Si2O37): A new mineral related to sillimanite from pegmatites in granulite-facies rocks. American Mineralogist. 1998. Vol. 83. Iss. 5-6, p. 638-651. DOI: 10.2138/am-1998-5-623

- Grew E., Carson C. A treasure trove of minerals discovered in the Larsemann Hills. Australian Antarctic Magazine. 2007. Iss. 13, p. 18-19.

- Bose S., Mondal A. K., Bakshi A.K., Jose J.R. Petrogenetic re-examination of spinel + quartz assemblage in the Larsemann Hills, East Antarctica. Polar Science. 2020. Vol. 26. N 100588. DOI: 10.1016/j.polar.2020.100588

- London D., Evensen J.M. Beryllium in Silicic Magmas and the Origin of Beryl-Bearing Pegmatites. Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry. 2002. Vol. 50. N 1, p. 445-486. DOI: 10.2138/rmg.2002.50.11

- London D. Crystal-Filled Cavities in Granitic Pegmatites: Bursting the Bubble. Rocks & Minerals. 2013. Vol. 88. Iss. 6, p. 527-538. DOI: 10.1080/00357529.2013.826090

- Evdokimov A.N., Yosufzai A. Geological Position of Rare-Metal Pegmatites of the Laghman Granitoid Complex, Afghanistan. Russian Journal of Earth Sciences. 2025. Vol. 25. N 1. N ES1002 (in Russian). DOI: 10.2205/2025ES000998

- Skublov S.G., Yosufzai A., Evdokimov A.N., Galankina O.L. Composition of Cs-rich analcime in spodumene pegmatites of Afghanistan (Kolatan Deposit, Nuristan province). Zapiski Rossiiskogo mineralogicheskogo obshchestva. 2024. Vol. 153. N 6, p. 122-140 (in Russian). DOI: 10.31857/S0869605524060053

- Grew E.S. Boron and beryllium minerals in granulite-facies pegmatites and implications of beryllium pegmatites for the origin and evolution of the Archean Napier Complex of East Antarctica. Memoirs of National Institute of Polar Research. 1998. Special Issue 53, p. 74-92.

- Kudryashov N.M., Galeeva E.V., Udoratina O.V. et al. The Archean stage of rare-metal (Li, Cs) pegmatite formation in the north-eastern part of the Fennoscandian Shield. Transactions of Karelian Research Centre of Russian Academy of Science. 2022. N 5, p. 68-72 (in Russian). DOI: 10.17076/geo1670

- Bea F., Montero P. Behavior of accessory phases and redistribution of Zr, REE, Y, Th, and U during metamorphism and partial melting of metapelites in the lower crust: an example from the Kinzigite Formation of Ivrea-Verbano, NW Italy. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 1999. Vol. 63. Iss. 7/8, p. 1133-1153. DOI: 10.1016/S0016-7037(98)00292-0

- Franz G., Morteani G. The Formation of Chrysoberyl in Metamorphosed Pegmatites // Journal of Petrology. 1984. Vol. 25. Iss. 1, p. 27-52. DOI: 10.1093/petrology/25.1.27

- Rybnikova O., Uher P., Novák M. et al. Chrysoberyl and associated beryllium minerals resulting from metamorphic overprinting of the Maršíkov–Schinderhübel III pegmatite, Czech Republic. Mineralogical Magazine. 2023. Vol. 87. Iss. 3, p. 369-381. DOI: 10.1180/mgm.2023.22

- Skublov S.G, Hamdard N., Ivanov M.A., Stativko V.S. Trace element zoning of colorless beryl from spodumene pegmatites of Pashki deposit (Nuristan province, Afghanistan). Frontiers in Earth Science. 2024. Vol. 12. N 1432222. DOI: 10.3389/feart.2024.1432222

- Rossovskii L.N., Shostatskii A.N. Pegmatites with chrysoberyl in one of the regions of Central Asia. Mineraly SSSR. 1964. Iss. 15, p. 154-161 (in Russian).

- London D. Reading Pegmatites: Part 1 – What Beryl Says. Rocks & Minerals. 2015. Vol. 90. Iss. 2, p. 138-153. DOI: 10.1080/00357529.2014.949173

- Ponomareva N.I., Gordienko V.V., Shurekova N.S. Physicochemical circumstances of beryl generation in “Bolshoy Lapot” deposit (Kola Peninsula). Vestnik Sankt-Peterburgskogo universiteta. Seriya 7. Geologiya. Geografiya. 2015. Iss. 3, p. 4-20 (in Russian).

- Gaafar I., Elbarbary M., Sayyed M.I. et al. Assessment of Radioactive Materials in Albite Granites from Abu Rusheid and Um Naggat, Central Eastern Desert, Egypt. Minerals. 2022. Vol. 12. Iss. 2. N 120. DOI: 10.3390/min12020120

- Carson C.J., Fanning C.M., Wilson C.J.L. Timing of the progress granite, Larsemann hills: Additional evidence for early Palaeozoic orogenesis within the east Antarctic Shield and implications for Gondwana assembly. Australian Journal of Earth Sciences. 1996. Vol. 43. Iss. 5, p. 539-553. DOI: 10.1080/08120099608728275

- Daniliev S.M., Mulev S.N., Shnyukova O.M. Correlation and regression analysis of natural electromagnetic and acoustic emission activity in rock samples of the Oktyabrsky deposit. Gornyi zhurnal. 2024. N 9, p. 51-55 (in Russian). DOI: 10.17580/gzh.2024.09.08

- Yakovleva A.A., Movchan I.B., Medinskaia D.K., Sadykova Z.I. Quantitative interpretations of potential fields: from parametric to geostructural recalculations. Bulletin of the Tomsk Polytechnic University. Geo Assets Engineering. 2023. Vol. 334. N 11, p. 198-215 (in Russian). DOI: 10.18799/24131830/2023/11/4152

- Davydkina T.V., Yankilevich A.A., Naumova A.N. Specifics of magnetotelluric studies in Antarctica. Journal of Mining Institute. 2025. Vol. 273, p. 80-93.

- London D., Hunt L.E., Duval C.L. Temperatures and duration of crystallization within gem-bearing cavities of granitic pegmatites. Lithos. 2020. Vol. 360-361. N 105417. DOI: 10.1016/j.lithos.2020.105417

- Bea F., Fershtater G., Corretgé L.G. The geochemistry of phosphorus in granite rocks and the effect of aluminium. Lithos. 1992. Vol. 29. Iss. 1-2, p. 43-56. DOI: 10.1016/0024-4937(92)90033-U

- Rogova I.V., Stativko V.S., Petrov D.A., Skublov S.G. Trace Element Composition of Zircons from Rapakivi Granites of the Gubanov Intrusion, the Wiborg Massif, as a Reflection of the Fluid Saturation of the Melt. Geochemistry International. 2024. Vol. 62. N 11, p. 1123-1136. DOI: 10.1134/S0016702924700630