Seismicity of tectonic structures of the South Polar Region

- 1 — Ph.D. Leading Researcher Schmidt Institute of Physics of the Earth, RAS ▪ Orcid ▪ Elibrary ▪ Scopus ▪ ResearcherID

- 2 — Ph.D. Senior Researcher Schmidt Institute of Physics of the Earth, RAS ▪ Orcid

Abstract

The paper studies seismicity of the South Polar Region from the South Pole to the 50th parallel of south latitude. During the observation period, earthquakes of various genesis with a magnitude of M > 8 occurred in seismically hazardous zones of the Southern Ocean – the South Sandwich subduction zone, the Macquarie Ridge and the Antarctic Ridge. These events can cause significant tsunamis. The Macquarie Ridge is characterized by a shear mechanism of the earthquake source, while different mechanisms were obtained for the Sandwich subduction zone region. During the instrumental observation period, weak intracontinental seismicity of Antarctica was recorded, which refutes the position of aseismicity of this continent. Seismicity is observed at the boundaries of tectonic blocks or is confined to coastal areas. In the continental intraplate region of Antarctica, earthquakes occur in several settings. The events in the Transantarctic Mountains and some subglacial rift basins, as well as isolated events in the central part of the continent, are probably tectonic. Seismicity in the coastal zone and on the continental margin may be related to glacial isostatic adjustment with a regional tectonic component in some places. The seismicity observed in Antarctica is low compared to other continental intraplate regions. The strongest events within the continent have a magnitude of 5-6. The authors identified intracontinental areas of increased seismicity. A correlation between intracontinental seismicity and subglacial basins of East Antarctica is shown. Some events with magnitudes below the threshold are not recorded. In addition, seismicity is partially suppressed by a thick ice cover.

Funding

The study was carried out under the State assignment of the Schmidt Institute of Physics of the Earth, RAS.

Introduction

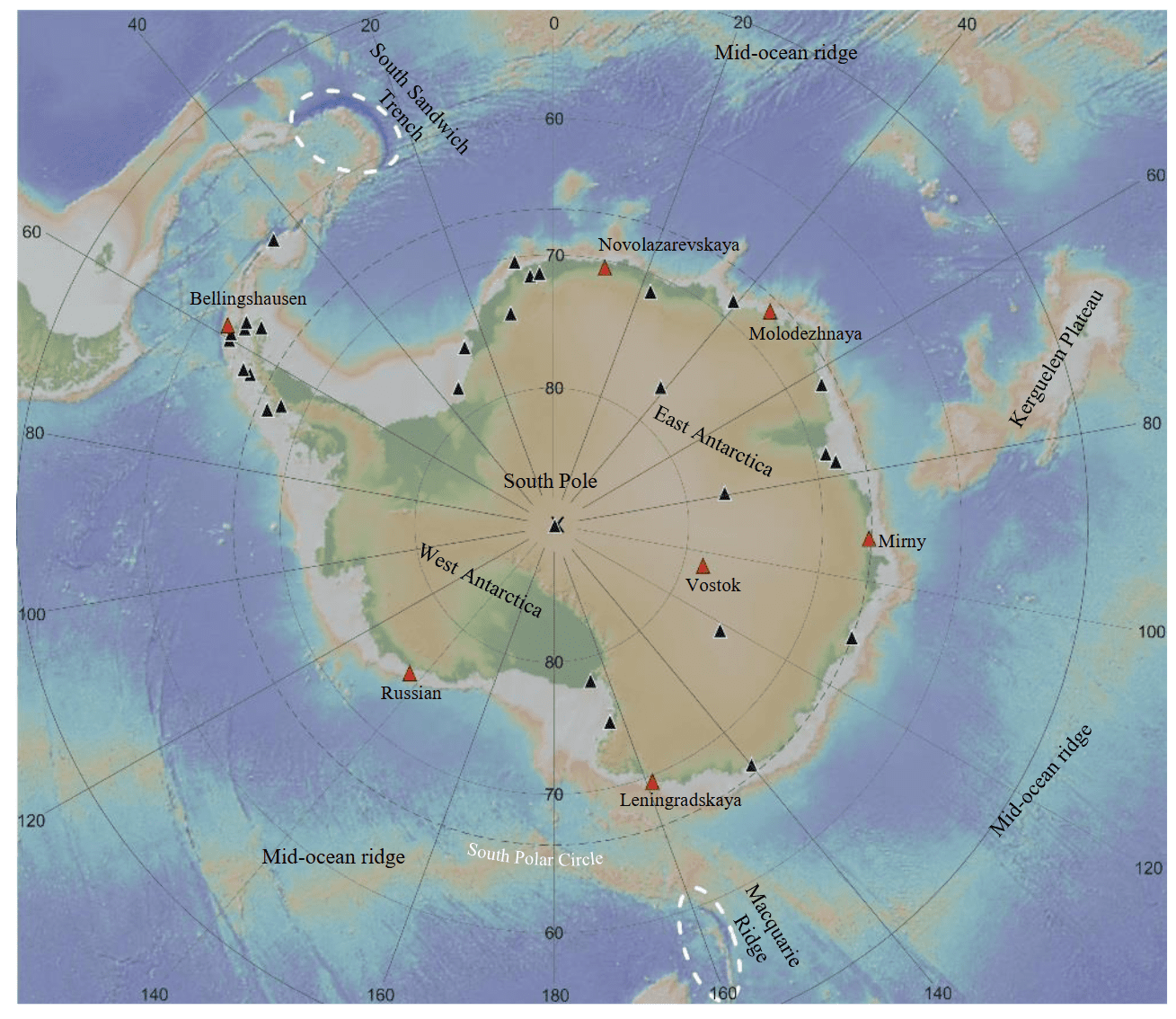

The Antarctic Plate, the fifth largest of all lithospheric plates, extending over an area of approxi-mately 60×106 km2, is mainly surrounded by mid-ocean ridge systems and is bordered by the plates Nazca, South American, Somali, African, Australian, Pacific, Juan Fernandez, Scotia, as well as Sandwich and Shetland microplates. Subduction zones are currently largely absent, except for the Antarctic tectonic margins with the South American, Scotia, and Shetland microplates [1]. Thus, most of the plate boundary is made up of either mid-ocean ridges or transform faults. The Antarctic Plate includes Antarctica, located roughly in the center; the Kerguelen Plateau; isolated volcanic islands and a part of the Southern Ocean (Fig.1).

Fig.1. General map of the South Polar Region (based on [4] with additions). White ovals are areas that generate tsunamis from strong seismic events; red triangles are the locations of Russian stations; black ones are foreign seismic stations operating in Antarctica

The formation of the Antarctic Plate began during the breakup of the supercontinent Gondwana [2, 3]. During the breakup of Gondwana, Antarctica moved south, forming and developing a divergent boundary with Australia. The rupture of the continental isthmus between Antarctica and South America about 35 million years ago, as well as the opening of the ocean between Australia and Antarctica, led to the isolation of Antarctica, the emergence of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (Western Wind Current), followed by complete glaciation and general cooling of the climate [5, 6]. Currently, the prevailing horizontal movement of the Antarctic Plate is estimated at about 1 cm/year towards the Atlantic Ocean [7-9].

Antarctica contains rocks of varying ages and origins, from the Archean to the Cenozoic [10]. Antarcticaʼs area is about 14×106 km2, and the ice sheet covers almost the entire continent, hiding the subglacial terrain and tectonic structures [11]. Bedrock is exposed mainly near the coast and in the mountains. The thickness of the crust and sediments varies greatly depending on the tectonic block and its evolution. West Antarctica is characterized by the presence of thinned crust, large and deep sedimentary basins [12, 13], and a wide distribution of volcanoes of various types, including subglacial ones [14, 15]. The lithosphere beneath West Antarctica is highly heterogeneous and predominantly thinned [16-18], and the heat flow is elevated [19-21]. East Antarctica is a more stable continental block, but areas of thinned crust and sedimentary basins have also been identified there [12, 13]. The lithosphere and heat flow of East Antarctica are also heterogeneous [18-20].

For a long time, there was a concept of aseismicity in Antarctica. The seismicity of the South Polar Region is poorly studied due to its inaccessibility. There are few permanent seismic stations and their distribution is uneven, and seasonal seismic measurements are associated with complex logistics and harsh climatic conditions both on land and at sea. In addition, there are few islands in the Southern Ocean where seismic stations can be located. Due to the active development of global seismic networks (GSN) and an increase in the number of local seismic stations in the Antarctic region, the data flow has increased. In particular, a local seismic network was deployed around the Neumayer III station, seismic observations were carried out by India at the Maitri station, and the Australians developed a broadband seismic network covering a large region between the Mawson and Casey stations, stretching to 75 deg S [22].

With the increase in the number of stations, intracontinental seismicity was discovered, not related to the location of active volcanoes [23, 24]. The latest catalog of seismic events in Antarctica for the period 1 January 2000 – 1 January 2021 contains about 60,000 events with magnitudes from 1 to 4.5 [25].

In central regions, where the ice is several kilometers thick [26], seismicity is suppressed by the ice cover, but rare events with magnitudes of 4 or more have been detected. This paper studies the seismicity of the South Polar Region and its relationship with tectonic structures. Seismicity in Antarctica and the Southern Ocean is analyzed using data collected by the International Seismological Center (ISC) [27, 28]. The relationship between seismicity and various tectonic structures on land and in the ocean is studied.

Research area

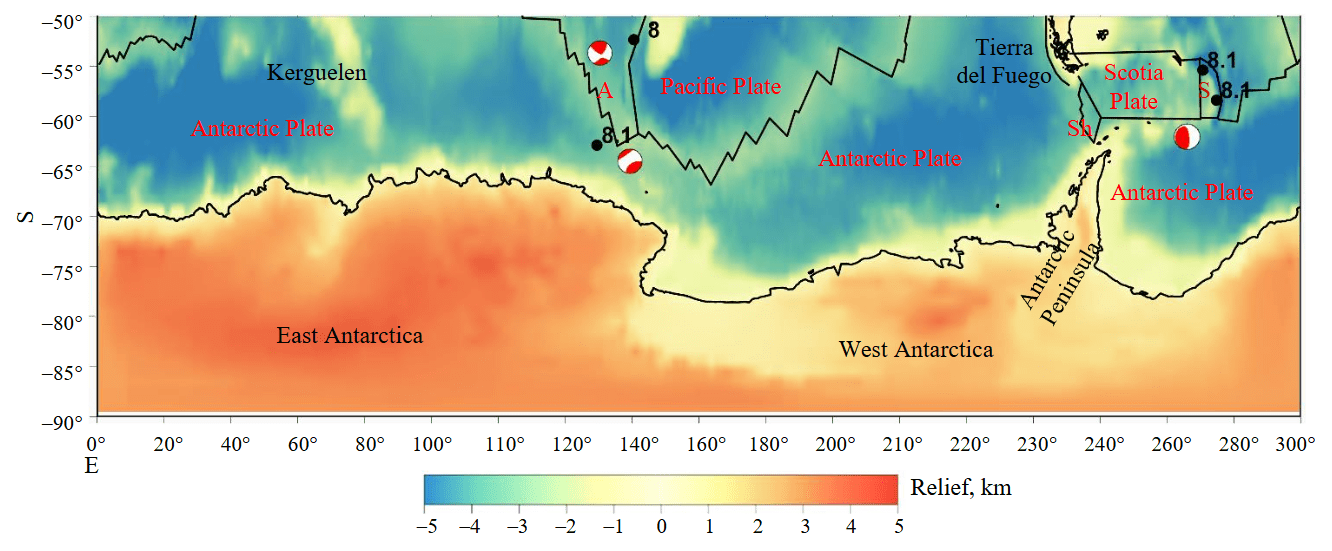

The main object of the study is seismic events in the South Polar Region. In turn, seismicity is determined by the stress state of the region and the rheology of its blocks. Strong earthquakes occur mainly at the boundaries of lithospheric plates (Fig.2). In the South Polar Region, most events are recorded in the Sandwich subduction zone, as well as in the area of the Antarctic Mid-ridge and the Macquarie Ridge [28, 29]. Here, events with a magnitude of Мw > 8 were found. Let us consider the strongest earthquakes of the South Polar Region. Fig.2 shows earthquakes with Mw > 8 south of 50 deg S. Four earthquakes with Mw > 8 occurred south of the 50th parallel: two in the Sandwich subduction zone (1929, Mw = 8.1; 2021, Mw = 8.1); one in the Macquarie Ridge area (1989, Mw = 8) and one in the Balleny Islands area (1998, Mw = 8.1) inside the Antarctic Plate (see Table).

Seismic events with Mw > 8 in the South Polar Region during the instrumental observation period

|

Date |

Time |

Latitude, deg |

Longitude, deg |

Depth, km |

Mw |

Region |

|

27.06.1929 |

12:47:13 |

–55.373 |

–29.345 |

15 |

8.1 |

The South Sandwich Islands arc |

|

23.05.1989 |

10:54:46 |

–52.341 |

160.568 |

10 |

8.0 |

Macquarie Ridge |

|

25.03.1998 |

3:12:25 |

–62.877 |

149.527 |

10 |

8.1 |

The Balleny Islands |

|

12.08.2021 |

18:35:17 |

–58.3753 |

–25.2637 |

23 |

8.1 |

The South Sandwich Islands arc |

Fig.2. Earthquakes in the South Polar Region (south of 50° S) for the period 1900-2024 with Mw > 8 according to the ISC catalog [27, 28]. Black line – plate boundaries; A – Australian Plate; S – Sandwich Microplate; Sh – Shetland Microplate. Focal mechanisms are given for those events for which data are available

The 2021 Sandwich arc earthquake (12.08.2021, Mw = 8.1, h = 23 km) caused a significant tsunami, recorded in the Pacific, Atlantic, and Southern oceans at once for the first time since the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami [30].

The focal mechanism solution is defined as a thrust fault close to a cut (one of the nodal surfaces is almost vertical [31-33]. The earthquake occurred at a depth of approximately 23 km in the Sandwich subduction zone 3 min after a foreshock with a magnitude of Mw = 7.5, which was located at a depth of ~63 km and ~90 km to the north. In the area of the earthquake, the South American Plate is subducting westward under the Scotia plate at a rate of ~7 cm/year relative to the plate.

Within 24 h of the Mw = 8.1 mainshock, 61 aftershocks with magnitudes Mw = 4.5 or greater were detected. The aftershock sequence during this period includes three with magnitudes of at least 6 (Mw = 6, Mw = 6.2, and Mw = 6.3). The aftershocks span a trench-parallel distance of approximately 470 km, extending from the Mw = 7.5 foreshock south to the triple junction between the South American, Scotia, and Antarctic plates.

The Macquarie Ridge earthquake (23.05.1989, Mw = 8, h = 10 km) has a strike-slip mechanism with a small reverse component. This event is one of the strongest strike-slip earthquakes in magnitude [34]. The fault is estimated to be about 120 km long. The rupture propagated from south to north at a relatively high speed. A large strike-slip earthquake like this produces significant vertical displacements on the ocean floor and generates tsunamis. In fact, small tsunamis have been observed off the southern coast of Australia.

The earthquake (25.03.1998, Mw = 8.1, h = 10 km) occurred in the Balleny Islands region, near the triple junction of the Antarctic Ridge with the Macquarie Ridge. This strong oceanic intraplate earthquake also has a normal fault solution of the focal mechanism, but with a small strike-slip component [35, 36], and is characterized by complex behavior with rupture into several fault segments.

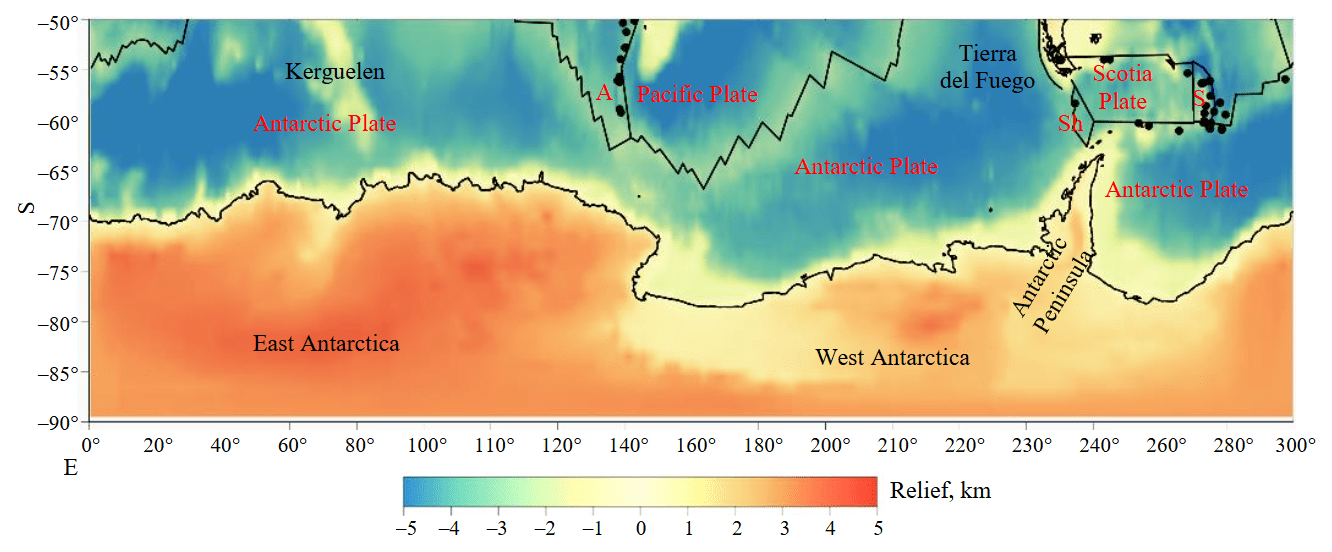

Figure 3 shows earthquakes with Mw > 7 south of 50° S. Events with Mw > 7 were recorded in two areas: in the Macquarie Ridge region on the boundary of the Australian and Pacific plates (transform fault) and along the boundaries of the Scotia Plate, including the Sandwich Microplate (see Fig.1-3).

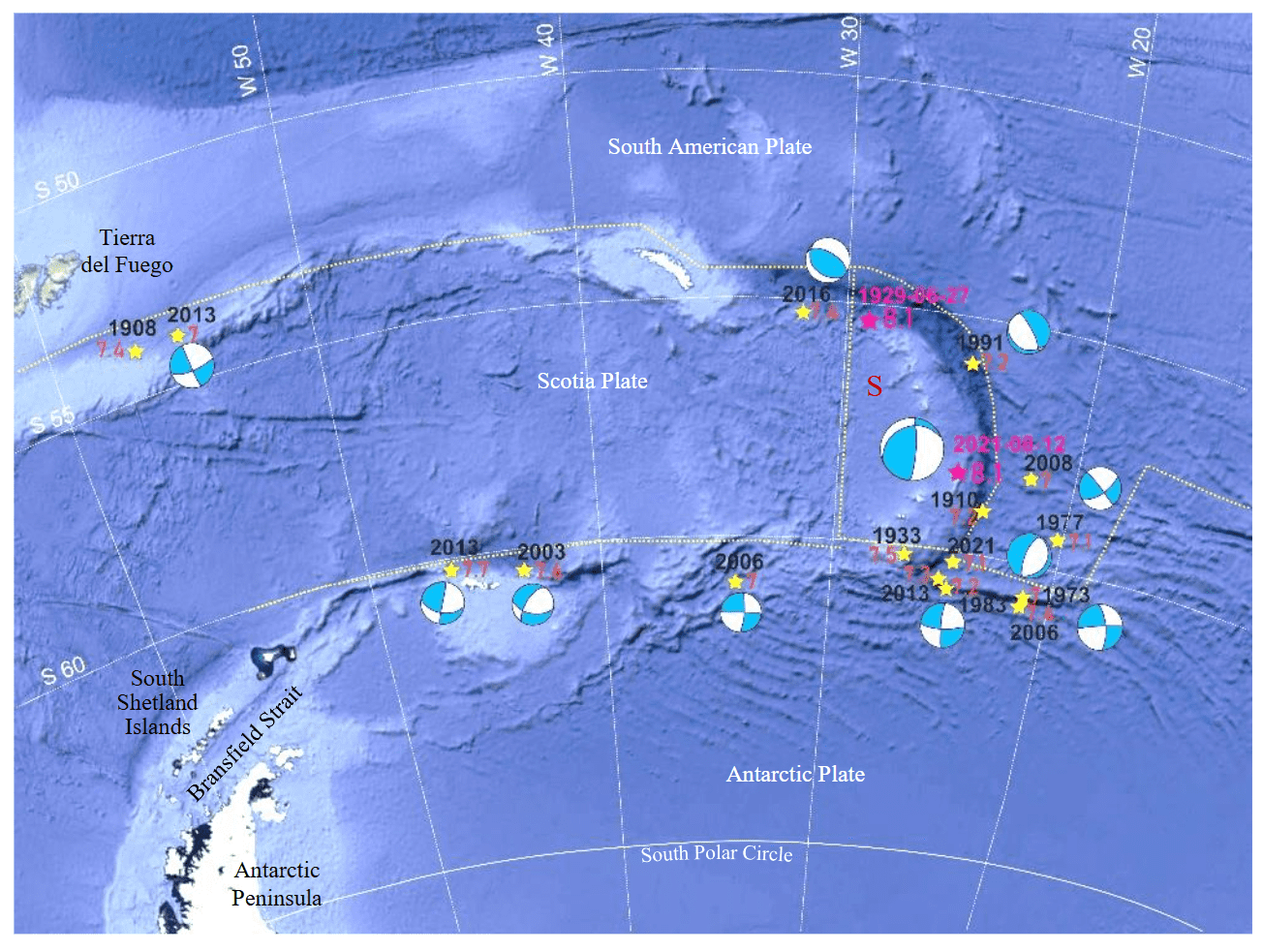

Figure 4 shows in more detail earthquakes with Mw > 7 south of 50 deg S for the Scotia Plate region with a depth of up to 30 km according to the ISC catalog [27, 28]. The focal mechanisms are different: on the northern and southern boundaries of the Scotia Plate, the strike-slip type predominates; in the Sandwich Trench area, the distribution of focal mechanism types is more diverse – there are events with normal, thrust, strike-slip types as well as an intermediate type of movement in the form of oblique fault.

Swarms of relatively weak earthquakes associated with volcanic eruptions have also been re-corded. For example, in the second half of 2020, seismic activity suddenly arose in the form of a large swarm of small-magnitude earthquakes amounting to more than 80,000 tremors that occurred near the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula [37, 38]. This phenomenon has been proposed to be explained by the awakening of a “sleeping” underwater volcano located under the seabed in the Bransfield Strait between the South Shetland Islands and the northwestern tip of Antarctica.

Fig.3. Earthquakes in the South Polar Region (south of 50° S) for the period 1900-2024 with 7 < Mw < 8 according to the ISC catalog [27, 28]. See Fig.2 for legend

Fig.4. Seismic events in the Scotia Plate area Mw ≥ 7 with a depth of up to 30 km according to the ISC catalog [27, 28].

S – Sandwich Microplate; yellow stars indicate epicenters of earthquakes with 7 ≤ Mw < 8, pink ones – with Mw ≥ 8. The sizes of the focal mechanism designations correspond to different magnitudes – large for Mw ≥ 8, smaller – Mw ≥ 7

Intracontinental seismicity

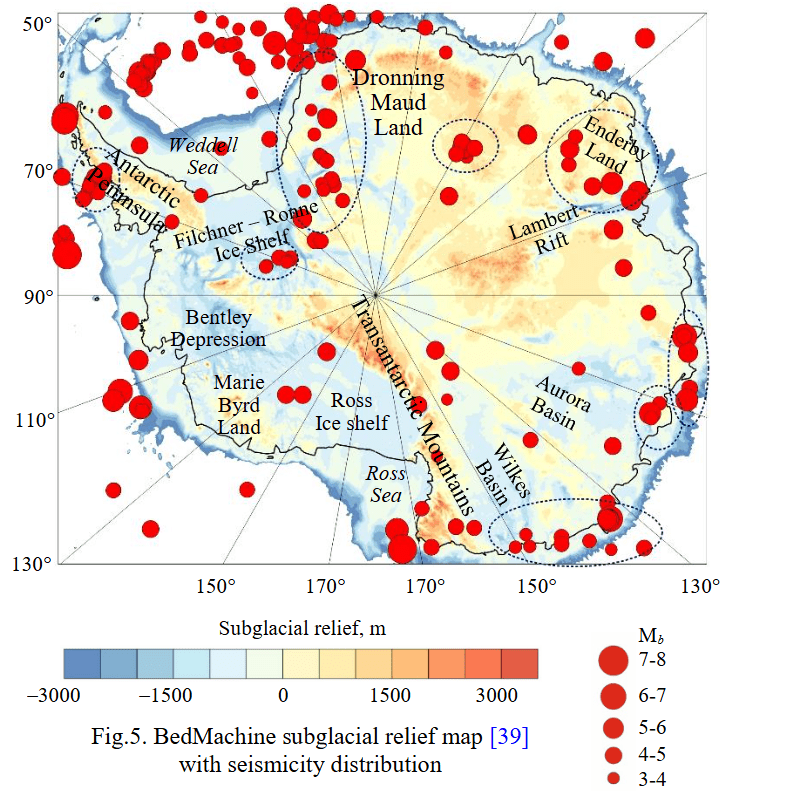

Figure 5 shows seismicity for the entire period of instrumental observations from 1907 to 2024, according to the ISC catalog [27, 28] with Mb > 3 for Antarctica and coastal areas.

The unification of magnitudes for weak events was carried out, to the magnitude Mb using independently derived formulas based on correlation dependencies: Mb = 0.95, Mw = 0.11, the correlation coefficient was 0.73; Mb = 1.29, Ms = 1.75, the correlation coefficient was 0.92.

Fig.5. BedMachine subglacial relief map [39] with seismicity distribution

Weak seismic events are mainly concentrated near the coast of the continent, but there are also rare events inside the continent. In coastal areas, events with a magnitude of Mb > 5 have been recorded. At the same time, in the central areas, where the ice is several kilometers thick, seismicity is suppressed by the ice cover, but rare events with magnitudes up to 5 have been detected. The main areas with a concentration of seismi-city are highlighted by black ovals in Fig.5.

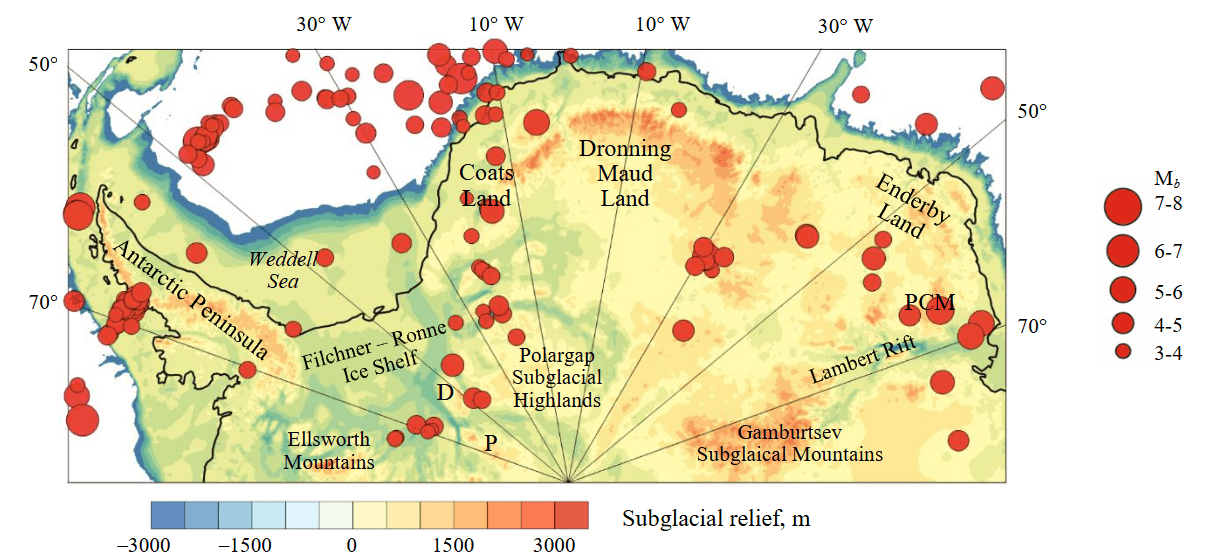

Figure 6 shows earthquakes with Mb > 3 south of 65° S of the Indo-Australian Block of East Antarctica and part of West Antarctica (the Antarctic Peninsula, the Ellsworth Mountains and Filchner – Ronne Ice Shelf). Seismicity at the boundary of West and East Antarctica in the area of Coats Land is associated with ongoing tectonic processes – rifting in narrow subglacial basins of Coats Land. Further south, seismicity is also associated with basins around the boundaries of the Filchner – Ronne Basin with the Dufek Block and the Pensacola Mountains. Further to the east, compact seismicity with magnitudes greater than 4 of unknown genesis was discovered in the central part of Dronning Maud Land.

Fig.6. Seismicity of a part of West Antarctica and the Indo-Antarctic Block of East Antarctica

D – Dufek Block; P – Pensacola Mountains; PCM – Prince Charles Mountains

The seismicity of Enderby Land in the Prince Charles Mountains region is probably related to their vertical uplift caused by rifting processes in the Lambert Basin. Weak events are mainly concentrated near the coast, but there are also rare events within the continent. In the middle of the Antarctic Peninsula there is an area of compact weak seismicity of unknown genesis. This may be a manifestation of subglacial volcanic activity, similar to the volcanic swarm in the Bransfield Strait (see Fig.4).

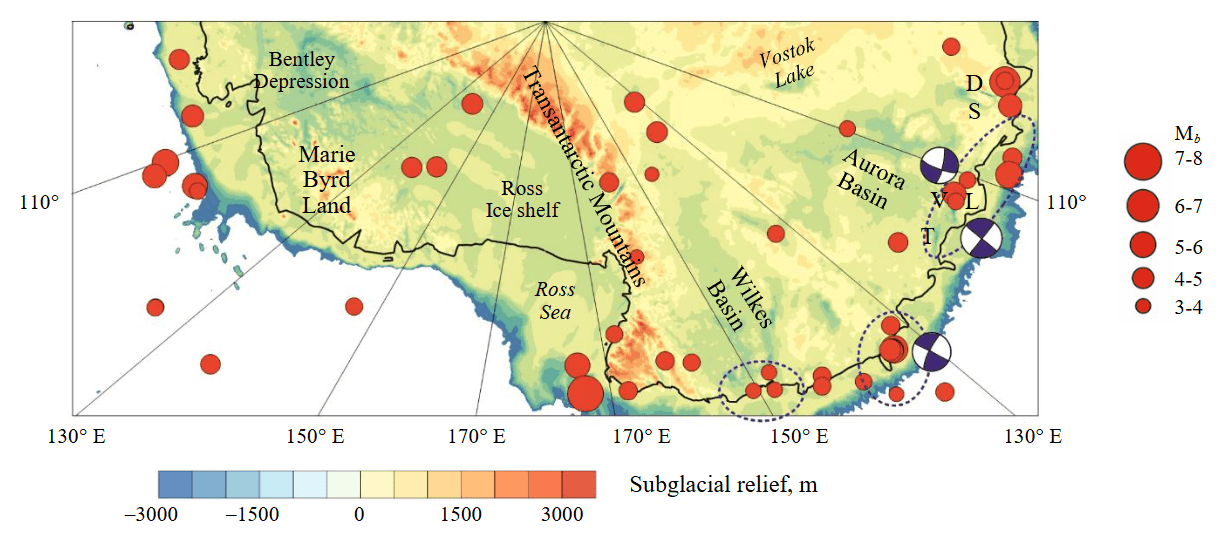

In the Australo-Antarctic Block of East Antarctica, a significant number of seismic events have been recorded in some coastal areas (Fig.7). Thus, in the area where the Denman and Scott glaciers reach the coast, several events have been detected, including 05.02.1977, Mb = 6.2, h = 27 km. To the east, near the coast, for the Vanderford and Totten basins on the boundary with the Low tectonic block, earthquake foci are concentrated in the axial part of the rift, but earthquakes are also noted in the sides of the Vanderford – Totten Depression. The strongest event in this area (04.11.2007, Mb = 5.7, h = 10 km) has a strike-slip mechanism of the focal point [27, 28]. Another event is characterized by a predominantly strike-slip mechanism – 19.05.1984, Mb = 5.1, h = 33 km. To the east, the coastal part of the Wilkes Basin is characterized by moderate seismicity with magnitudes up to 5. The strongest event detected in this area (22.02.2005, Mb = 5.4, h = 10 km) also has a strike-slip mechanism (Fig.7).

Fig.7. Seismicity of the part of West Antarctica and the Australo-Antarctic Block of East Antarctica

D – Denman Depression; S – Scott Depression; V – Vanderford Depression; T – Totten Depression; L – Low Dome

Genesis of seismically active structures

For many decades, Antarctica was considered an aseismic continent. However, recently, small earthquakes have been detected on the Antarctic continent, although the activity is much weaker than on other continents. The number of tectonic earthquakes recorded in Antarctica has increased with the development of seismic networks and local seismic measurements.

Antarctic seismicity may have several controlling factors – tectonic forces acting on the Earth’s plates, including contrasting tectonic province boundaries and major faults; and forces caused by the loading and partial unloading of the ice sheet that dominates the continent. Analysis of the spatial distribution of Antarctic earthquakes lags decades behind other continents due to the lack of global seismic network stations in the Southern Hemisphere and the difficulty of operating temporary seismic networks in Antarctica’s inhospitable interior. Analysis of source mechanisms lags even further due to the low magnitudes of the earthquakes.

Seismicity within each tectonic setting allows us to divide the study area into five regions: highly seismic along the Scotia Plate boundaries; highly seismic in the Macquarie Ridge region; low-seismic coastal regions of Antarctica; continental low-seismic regions; low-seismic region of the marine part of the Antarctic Plate far from the boundaries.

Intraplate earthquakes can have different natures. Shallow earthquakes are usually observed along faults, while deep-focus events occur in the plate subducting into the mantle and are associated with deformations in it. The earthquake of 25.03.1998, Mw = 8.1, h = 10 km [35, 36] was caused by the extension of the Antarctic plate, which occurs from the triple Antarctic Ridge with the Macquarie Ridge to the south towards the Transantarctic Mountains.

The obtained data suggest that intracontinental events are associated with the boundaries of tectonic blocks, mainly with active rifts [40-42], while seismicity along the coasts is associated with isostatic glacial adjustment and calving of large icebergs. Most tectonic earthquakes along the Antarctic coast are caused by residual stresses accumulated after partial deglaciation in the Holocene. The opposite effect is also possible: a tectonic event can trigger the onset of iceberg calving, underwater landslide, or acceleration of sliding of an unstable ice sheet. In turn, a landslide or glacier calving can be initiated by a moderate seismic event. Such phenomena can be accompanied by significant tsunamis.

Now, comprehensive studies are being conducted in the area of Lake Vostok [43]. In particular, modeling of the geomechanical interaction of the ice sheet with the underlying water and solid surface is being carried out [44].

Discussion and conclusions

Seismicity in Antarctica and the Southern Ocean is analyzed based on ISC catalog data for the period from 1900 to 2024. Within the Antarctic Plate, the strongest earthquake occurred near the Balleny Islands (25.03.1998, Mw = 8.1). Low-magnitude seismicity prevails on the Antarctic continent, but there are events with M > 5. Seismic events are grouped into several regions and in the coastal zone. Intracontinental seismicity is caused by tectonic processes and icequakes. Tectonic events are associated with crustal block boundaries, including active rifts, while coastal seismicity may be a consequence of tectonic unloading due to glacier melting in the Holocene. Recorded seismicity confirms the current activity of the Coats Land rifts, Lambert, Scott, Denman, Vanderford, and Totten rifts.

The entire South Polar Region has significant seismicity. The Sandwich Trench and Macquarie Ridge generate events with Mw > 8, which pose a significant tsunamigenic hazard. Numerous events with magnitude Mw > 7 with various focal mechanisms have been recorded in these same areas of the Southern Ocean. The question of possible events with Mw > 8.5 in the Sandwich subduction zone and Macquarie Ridge remains open. None of the named events resulted in fatalities due to the distance from populated areas vulnerable to earthquakes and tsunamis.

An important result is the discovery of two earthquake swarms – a volcanic one in the Bransfield Strait at the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula and one on the coast of the peninsula to the south. It is necessary to take into account the poor coverage of the South Polar Region by seismic stations, since some events were not included in seismic catalogs. More seismic stations in the region are needed for more detailed studies.

References

- Altamimi Z., Métivier L., Rebischung P. et al. ITRF2014 plate motion model. Geophysical Journal International. 2017. Vol. 209. Iss. 3, p. 1906-1912. DOI: 10.1093/gji/ggx136

- Storey B.C., Granot R. Chapter 1.1 Tectonic history of Antarctica over the past 200 million years. Volcanism in Antarctica: 200 Million Years of Subduction, Rifting and Continental Break-up. London: The Geological Society, 2021. Vol. 55, p. 9-17. DOI: 10.1144/M55-2018-38

- Leitchenkov G.L., Dubinin E.P., Grokholsky A.L., Agranov G.D. Formation and Evolution of Microcontinents of the Kerguelen Plateau, Southern Indian Ocean. Geotectonics. 2018. Vol. 52. N 5, p. 499-515. DOI: 10.1134/S0016852118050035

- Ryan W.B.F., Carbotte S.M., Coplan J.O. et al. Global Multi-Resolution Topography synthesis. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems. 2009. Vol. 10. N 3. N Q03014. DOI: 10.1029/2008GC002332

- Pérez L.F., Bohoyo F., Hernández-Molina F.J. et al. Tectonic activity evolution of the Scotia-Antarctic Plate boundary from mass transport deposit analysis. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth. 2016. Vol. 121. Iss. 4, p. 2216-2234. DOI: 10.1002/2015JB012622

- Levitan M.A., Leichenkov G.L. Cenozoic Glaciation of Antarctica and Sedimentation in the Southern Ocean. Lithology and Mineral Resources. 2014. Vol. 49. N 2, p. 117-137. DOI: 10.1134/S0024490214020060

- Savchyn I., Brusak I., Tretyak K. Analysis of recent Antarctic plate kinematics based on GNSS data. Geodesy and Geodynamics. 2023. Vol. 14. Iss. 2, p. 99-110. DOI: 10.1016/j.geog.2022.08.004

- Savchyn I. Establishing the correlation between the changes of absolute rotation poles of major tectonic plates based on conti-nuous GNSS stations data. Acta Geodynamica et Geomaterialia. 2022. Vol. 19. № 2 (206), p. 167-176. DOI: 10.13168/AGG.2022.0006

- Young A., Flament N., Maloney K. et al. Global kinematics of tectonic plates and subduction zones since the late Paleozoic Era. Geoscience Frontiers. 2019. Vol. 10. Iss. 3, p. 989-1013. DOI: 10.1016/j.gsf.2018.05.011

- Leitchenkov G.L., Grikurov G.E. The Tectonic Structure of the Antarctic. Geotectonics. 2023. Vol. 57. Suppl. 1, p. S28-S33. DOI: 10.1134/S0016852123070087

- Morlighem M., Rignot E., Binder T. et al. Deep glacial troughs and stabilizing ridges unveiled beneath the margins of the Antarctic ice sheet. Nature Geoscience. 2020. Vol. 13. Iss. 2, p. 132-137. DOI: 10.1038/s41561-019-0510-8

- Baranov A., Tenzer R., Bagherbandi M. Combined Gravimetric–Seismic Crustal Model for Antarctica. Surveys in Geophysics. 2018. Vol. 39. Iss. 1, p. 23-56. DOI: 10.1007/s10712-017-9423-5

- Baranov A., Morelli A. The structure of sedimentary basins of Antarctica and a new three-layer sediment model. Tectonophysics. 2023. Vol. 846. N 229662. DOI: 10.1016/j.tecto.2022.229662

- van Wyk de Vries M., Bingham R.G., Hein A.S. A new volcanic province: an inventory of subglacial volcanoes in West Antarctica. Exploration of Subsurface Antarctica: Uncovering Past Changes and Modern Processes. London: The Geological Society, 2018. Vol. 461, p. 231-248. DOI: 10.1144/SP461.7

- Geyer A., Roberto A.D., Smellie J.L. et al. Volcanism in Antarctica: An assessment of the present state of research and future directions. Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 2023. Vol. 444. N 107941. DOI: 10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2023.107941

- Wiens D.A., Shen W., Lloyd A.J. The seismic structure of the Antarctic upper mantle. The Geochemistry and Geophysics of the Antarctic Mantle. London: The Geological Society, 2023. Vol. 56, p. 195-212. DOI: 10.1144/M56-2020-18

- Lucas E.M., Soto D., Nyblade A.A. et al. P- and S-wave velocity structure of central West Antarctica: Implications for the tectonic evolution of the West Antarctic Rift System. Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 2020. Vol. 546. N 116437. DOI: 10.1016/j.epsl.2020.116437

- Baranov A.A., Lobkovskii L.I., Bobrov A.M. Global Geodynamic Model of the Modern Earth and Its Application to the Antarctic Region. Doklady Earth Sciences. 2023. Vol. 512. Part 1, p. 854-858. DOI: 10.1134/S1028334X23601086

- Lösing M., Ebbing J., Szwillus W. Geothermal Heat Flux in Antarctica: Assessing Models and Observations by Bayesian Inversion. Frontiers in Earth Science. 2020. Vol. 8. N 105. DOI: 10.3389/feart.2020.00105

- Artemieva I.M. Antarctica ice sheet basal melting enhanced by high mantle heat. Earth-Science Reviews. 2022. Vol. 226. № 103954. DOI: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2022.103954

- Reading A.M., Stål T., Halpin J.A. et al. Antarctic geothermal heat flow and its implications for tectonics and ice sheets. Nature Reviews Earth & Environment. 2022. Vol. 3. Iss. 12, p. 814-831. DOI: 10.1038/s43017-022-00348-y

- Reading A.M. On Seismic Strain-Release within the Antarctic Plate. Antarctica. Springer, 2006, p. 351-356. DOI: 10.1007/3-540-32934-X_43

- Kanao M. Seismicity in the Antarctic Continent and Surrounding Ocean. Open Journal of Earthquake Research. 2014. Vol. 3. N 1, p. 5-14. DOI: 10.4236/ojer.2014.31002

- Mishra O.P. Seismo-Geophysical Studies in the Antarctic Region: Geodynamical Implications. Assessing the Antarctic Environment from a Climate Change Perspective. Springer, 2022, p. 287-341. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-030-87078-2_17

- Castro A.F.P., Schmandt B., Nakai J. et al. (Re)Discovering the Seismicity of Antarctica: A New Seismic Catalog for the Southernmost Continent. Seismological Research Letters. 2024. Vol. 96. N 1, p. 576-594. DOI: 10.1785/0220240076

- Frémand A.C., Fretwell P., Bodart J.A. et al. Antarctic Bedmap data: Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable (FAIR) sharing of 60 years of ice bed, surface, and thickness data. Earth System Science Data. 2023. Vol. 15. Iss. 7, p. 2695-2710. DOI: 10.5194/essd-15-2695-2023

- Storchak D.A., Giacomo D.D., Engdahl E.R. et al. The ISC-GEM Global Instrumental Earthquake Catalogue (1900–2009): Introduction. Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interiors. 2015. Vol. 239, p. 48-63. DOI: 10.1016/j.pepi.2014.06.009

- Giacomo D.D., Engdahl E.R., Storchak D.A. The ISC-GEM Earthquake Catalogue (1904–2014): status after the Extension Project. Earth System Science Data. 2018. Vol. 10. Iss. 4, p. 1877-1899. DOI: 10.5194/essd-10-1877-2018

- Bondár I., Engdahl E.R., Villaseñor A. et al. ISC-GEM: Global Instrumental Earthquake Catalogue (1900–2009), II. Location and seismicity patterns. Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interiors. 2015. Vol. 239, p. 2-13. DOI: 10.1016/j.pepi.2014.06.002

- Roger J.H.M., Jamelot A., Hébert H. et al. The South Sandwich Tsunami of 12 August 2021: An Underestimated Widespread Tsunami Hazard Around the World. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans. 2024. Vol. 129. Iss. 12. N e2024JC021433. DOI: 10.1029/2024JC021433

- Zhe Jia, Zhongwen Zhan, Hiroo Kanamori. The 2021 South Sandwich Island Mw 8.2 Earthquake: A Slow Event Sandwiched Between Regular Ruptures. Geophysical Research Letters. 2022. Vol. 49. Iss. 3. N e2021GL097104. DOI: 10.1029/2021GL097104

- Lutikov A.I., Gabsatarova I.P., Dontsova G.Yu., Zhukovets V.N. The Strong Earthquake of August 12, 2021, Mw = 8.3, near the Southern Sandwich Islands and Its Geodynamic Settings. Izvestiya, Atmospheric and Oceanic Physics. 2022. Vol. 58. Suppl. 1, p. S62-S77. DOI: 10.1134/S0001433822130059

- Metz M., Vera F., Carrillo Ponce A. et al. Seismic and Tsunamigenic Characteristics of a Multimodal Rupture of Rapid and Slow Stages: The Example of the Complex 12 August 2021 South Sandwich Earthquake. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth. 2022. Vol. 127. Iss. 11. DOI: 10.1029/2022JB024646

- Satake K., Kanamori H. Fault parameters and tsunami excitation of the May 23, 1989, MacQuarie Ridge Earthquake. Geophysical Research Letters. 1990. Vol. 17. Iss. 7, p. 997-1000. DOI: 10.1029/GL017i007p00997

- Henry C., Das S., Woodhouse J. H. The great March 25, 1998, Antarctic Plate earthquake: Moment tensor and rupture history. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth. 2000. Vol. 105. Iss. B7, p. 16097-16118. DOI: 10.1029/2000JB900077

- Hjörleifsdóttir V., Kanamori H., Tromp J. Modeling 3-D wave propagation and finite slip for the 1998 Balleny Islands earthquake. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth. 2009. Vol. 114. Iss. B3. N B03301. DOI: 10.1029/2008JB005975

- Cesca S., Sugan M., Rudzinski Ł. et al. Massive earthquake swarm driven by magmatic intrusion at the Bransfield Strait, Antarctica. Communications Earth & Environment. 2022. Vol. 3. N 89. DOI: 10.1038/s43247-022-00418-5

- Olivet J.L., Bettucci L.S., Castro-Artola O.A. et al. A seismic swarm at the Bransfield Rift, Antarctica. Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 2021. Vol. 111. N 103412. DOI: 10.1016/j.jsames.2021.103412

- Morlighem M., Rignot E., Binder T. et al. Deep glacial troughs and stabilizing ridges unveiled beneath the margins of the Antarctic ice sheet. Nature Geoscience. 2020. Vol. 13. Iss. 2, p. 132-137. DOI: 10.1038/s41561-019-0510-8

- Baranov A.A., Lobkovsky L.I. The Deepest Depressions on Land in Antarctica as a Result of Cenosoic Riftogenesis Activation. Doklady Earth Sciences. 2024. Vol. 514. Part 1, p. 38-42. DOI: 10.1134/S1028334X23602420

- Golynsky D.A., Golynsky A.V. Unique geological structures of the Law Dome and Vanderford and Totten glaciers region (Wilkes Land) distinguished by geophysical data. Arctic and Antarctic Research. 2019. Vol. 65. N 2, p. 212-231 (in Russian). DOI: 10.30758/0555-2648-2019-65-2-212-231

- Lough A.C., Wiens D.A., Nyblade A. Reactivation of ancient Antarctic rift zones by intraplate seismicity. Nature Geoscience. 2018. Vol. 11. Iss. 7, p. 515-519. DOI: 10.1038/s41561-018-0140-6

- Bolshunov A.V., Vasilev D.A., Dmitriev A.N. et al. Results of complex experimental studies at Vostok station in Antarctica. Journal of Mining Institute. 2023. Vol. 263, p. 724-741.

- Litvinenko V., Trushko V. Modelling of geomechanical processes of interaction of the ice cover with subglacial Lake Vostok in Antarctica. Antarctic Science. 2025. Vol. 37. Iss. 1, p. 39-48. DOI: 10.1017/S0954102024000506