Early stages of ocean formation between Australia and Antarctica

- 1 — Researcher VNIIOkeangeologia ▪ Orcid

- 2 — Ph.D., Dr.Sci. Deputy Director General VNIIOkeangeologia ▪ Orcid ▪ Elibrary ▪ Scopus ▪ ResearcherID

Abstract

The paper deals with geodynamic reconstructions of Australia and Antarctica (using the GPlates program) 79, 68-61, 48, 44, and 40 Ma based on the comparison of conjugate single-age magnetic anomalies. The relevance of the present study is determined by the increased scientific interest in the problems of Gondwana break-up and the influence of lithospheric block tectonics on the processes of riftogenesis and ocean opening. The early stage of oceanic opening between Australia and Antarctica is characterised by a series of distinct linear magnetic anomalies. Oceanic spreading occurred in an ultra-slow to slow regime with rates of 20-26 mm/year between 33o and 21u anomalies (80-48 Ma) and 40 mm/year between 21u and 18o anomalies (48-40 Ma). According to the studies, there is a clear correlation between the change in spreading rate and the position of the rotation poles. Between 80 and 48 Ma, the rotation pole was located to the west, in the Kerguelen Plateau region, and Australia shifted westward relative to Antarctica. About 48 million years ago, the rate of seafloor spreading almost doubled (from ultra-slow to slow), and Australia began to migrate northwards. The rotation pole was near the southern edge of Tasmania and continued to move southeast towards the Pacific Ocean. The separation of Australia and Antarctica was associated with the advance of the spreading axes of the Indian and Pacific oceans towards each other, with orthogonal inter-section of the ancient lithospheric blocks of the two continents, and was determined by the geometry of the marginal rift structures.

Introduction

Until the end of the Late Cretaceous, Australia and Antarctica constituted a single continent within the East Gondwana [1], which included the areas of the Archean cratons, Proterozoic-Palaeozoic orogens [2-7]. During the break-up of the Australo-Antarctic continent, rifting and subsequent oceanic spreading crossed all tectonic provinces (Fig.1), including the ancient Archean cratons with high lithospheric strength. Synchronous processes of advancing spreading axes from the Indian and Pacific oceans towards each other are responsible for the continuous separation [2, 8].

The aim of this study is to investigate the interaction of two counteracting spreading axes from the Pacific and Indian Oceans during the period 80-40 Ma and the influence of this interaction on the process of oceanic opening with the break-up of the Australo-Antarctic Palaeoplate, which took place in the regime of ultra-slow and unstable spreading [9-11]. The study is based on a series of palaeoreconstructions of Australia and Antarctica constructed by combining conjugate single-age-band (spreading) magnetic anomalies.

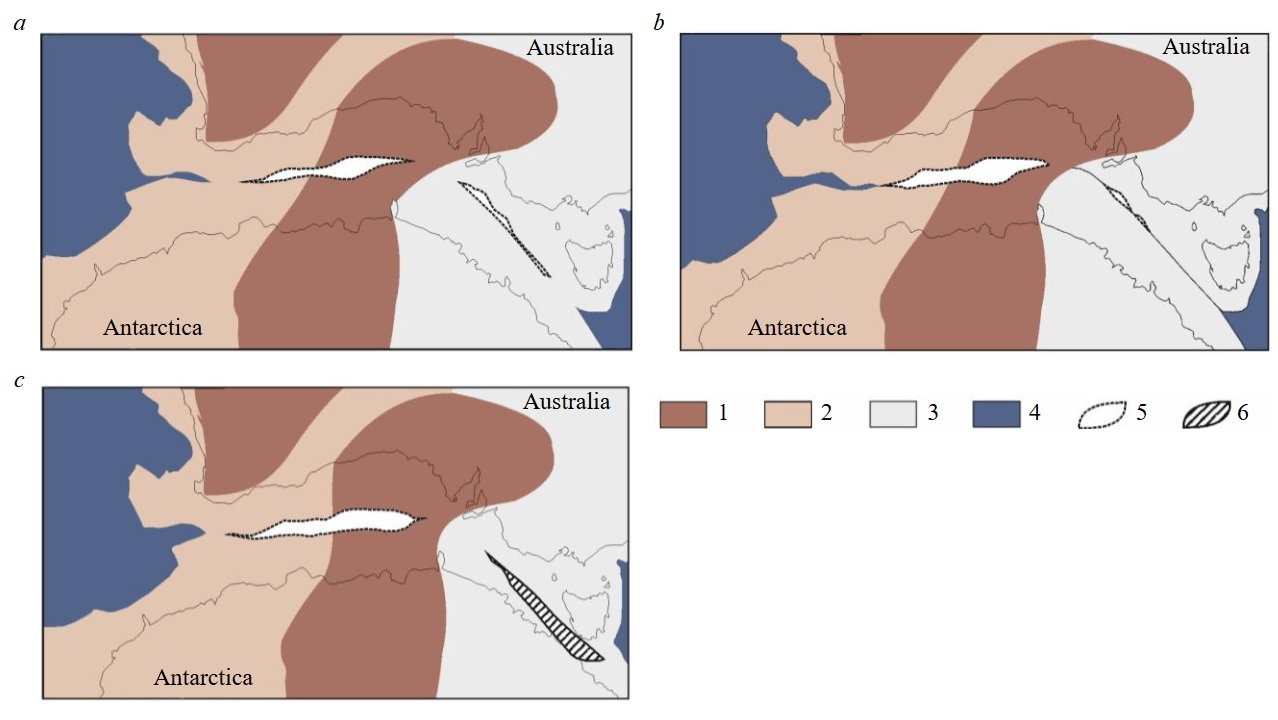

The position of Australia relative to Antarctica within a single lithospheric block and the early history of continental break-up are still debated [12]. The plate reconstructions proposed for the lithospheric rifting of the Australo-Antarctic continent around 80 Ma do not fully agree with the boun-daries between the continental and oceanic crusts (hereafter referred to as the continent-ocean boundary) inferred from geophysical data [3, 5, 6]. There are several models of the mutual position of Australia and Antarctica before spreading, and all the reconstructions proposed so far indicate the mismatch of the continent-ocean boundaries, with a gap in the central part of the divided Australo-Antarctic continent and an overlap in its western and eastern parts [4-6] (Fig.2).

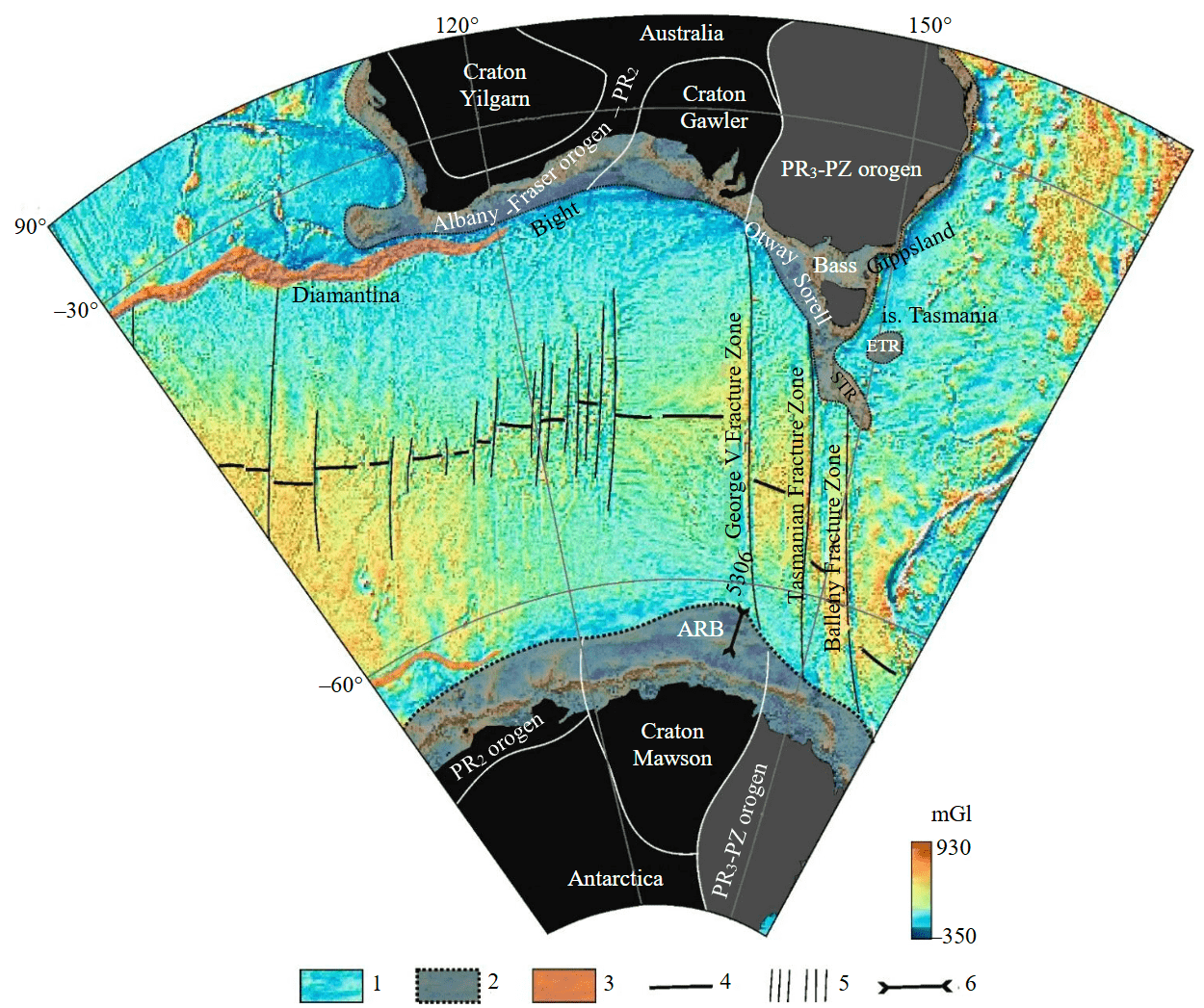

Fig.1. Main structural-tectonic elements of the south-eastern part of the Indian Ocean.

Based on the map of the gravity field (reduction in free air) obtained from satellite altimetry data [13]. The Archean cratons and Proterozoic-Palaeozoic orogens are shown on the continents [14]; on the continental margin of Australia, the sedimentary basins Bight, Otway, Sorell, Gippsland, Bass [2, 15]; on the continental margin of East Antarctica, the Adelie Rift Block (ARB) [16, 17]; near Tasmania Island are the East Tasmanian Rise (ETR) and the South Tasmanian Rise (STR)

1 – oceanic crust; 2 – shelf; 3 – amagmatic rises of oceanic crust; 4 – spreading axis; 5 – transform faults; 6 – seismic profile

Fig.2. Models of the mutual position of Australia and Antarctica at the time of lithospheric break-up between Australia and Antarctica: a – from [4]; b – from [5]; c – from [6]

1 – Archean cratons; 2 – Middle Proterozoic orogen; 3 – Late Proterozoic-Palaeozoic orogen; 4 – oceanic crust; 5 – gap; 6 – overlap

Geological and geophysical knowledge

Australo-Antarctic continent is composed of regions with different lithospheric rheological properties, and their break-up during ocean opening occurred under different geodynamic conditions. In the western part of the Australo-Antarctic continent, the area of Precambrian basement development consists of Archean cratons and, between them, Proterozoic orogens (see Fig.1). At least from the Early Palaeozoic to the mid-Late Cretaceous, the Australo-Antarctic continent was a single lithospheric block that was part of Gondwana [18, 19], with a thick and relatively cold lithosphere that provided increased resistance to destructive processes leading to supercontinent collapse.

The break-up of the Australo-Antarctic continent began with continental rifting, which lasted for a long time, 75-80 Ma. Rifting between Australia and Antarctica began in the west at 160-150 Ma and later in the east at 150-145 Ma [2]. As a result of the long continental rifting, extremely wide (300 to 500 km) conjugate amagmatic margins characterised by mantle exhumation were formed (Fig.3) [20-22]. The age of rifting has been determined from drilling data and analysis of seismic profiles in the Bight Basin (southwestern Australia) [21-23].

It is probably the high strength of the ancient, relatively cold lithosphere that determined the ultra-slow rates of continental rifting and subsequent oceanic spreading within the ancient part of the Australo-Antarctic plate.

The weaker Late Proterozoic-Palaeozoic orogen developed to the east of the Australo-Antarctic continent along the Pacific margin and had a blocky structure. Previously, the unified folded region was wider and included Zealandia, Lord Howe Rise, Chatham Rise and the Campbell Plateau [2] to the east of the region under discussion. The main rheological difference of this lithosphere was its structural heterogeneity and hotter upper mantle compared to the relatively monolithic upper mantle of the Archean-Middle Proterozoic. During the Early-Middle Cretaceous, a zone of the proto-Pacific subduction zone developed here until the Chatham Rise began to separate from Antarctica during the peri-period of normal polarity of the magnetic field (90-83 Ma) [25-27]. Later, the Campbell Plateau separated from the Antarctic margin (83-79.1 Ma) [28, 29]. Thus, by the time the Australo-Antarctic palaeocontinent began to break up at 80 Ma, there was intense an separation of small terranes within the Palaeozoic orogen on the Pacific Ocean side, and long-term slow continental rifting within the Archean-Middle Proterozoic lithosphere on the Indian Ocean side.

The onset of ocean spreading between Australia and Antarctica was preceded by exhumation of the continental lithospheric mantle of serpentinised peridotites. On the continental margin of Wilkes – George V Land and in the waters of the Great Australian Bight, the zones of mantle stripping have been identified, which are clearly manifested in the gravity field and anomalous magnetic field by positive long wave anomalies [21]. The magnetic anomaly over the mantle unroofing zone, extending over 1500 km, was previously identified as a C34-band magnetic anomaly of spreading origin [9]. The gravity anomaly above the exhumed lithospheric mantle confirms this conclusion, indicating the increased density of the exhumed mantle relative to the surrounding blocks of continental crust [21].

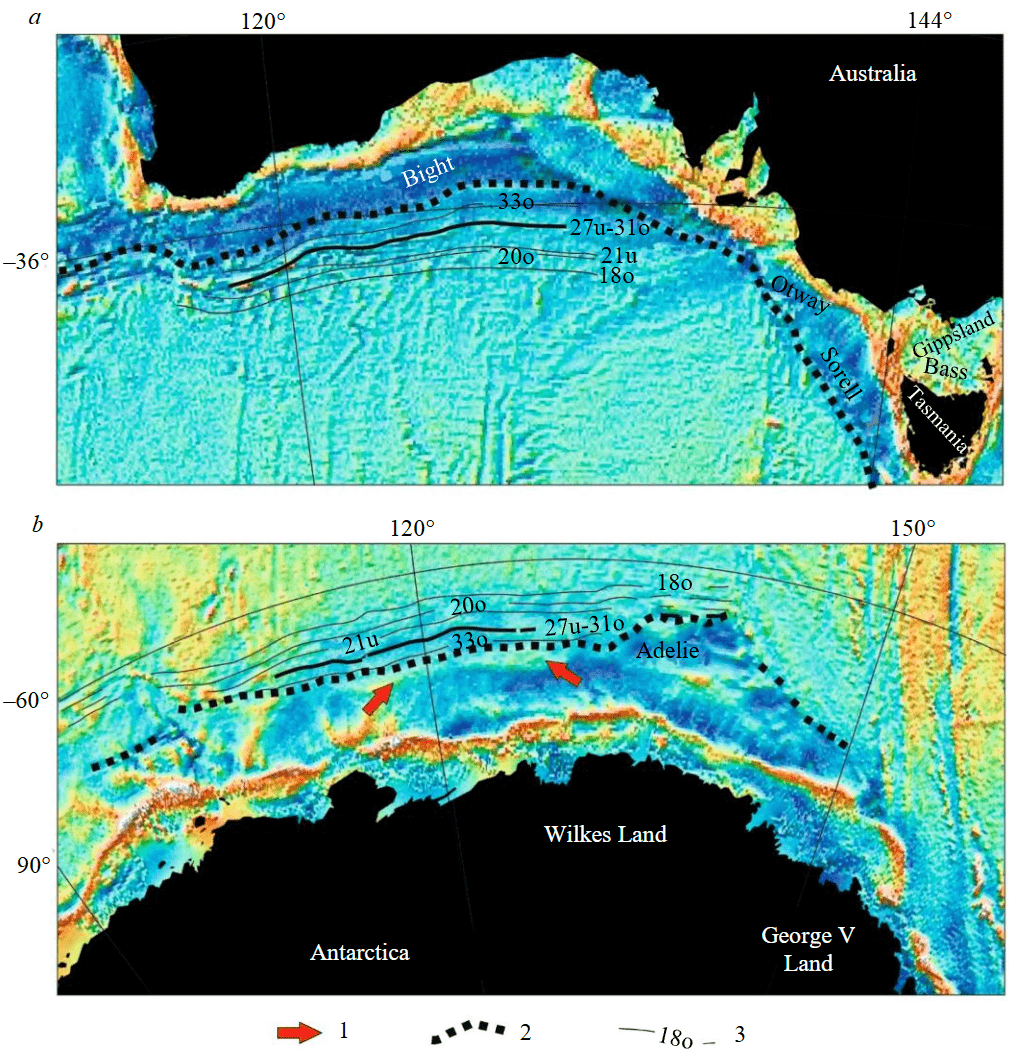

The early stage of oceanic opening between Australia and Antarctica is characterized by a sequence of distinct linear magnetic anomalies [21, 30, 31]. Oceanic spreading occurred in an ultra-slow to slow regime with rates of 20-26 mm/year between 33o and 21u anomalies (80-48 Ma) and 40 mm/year between 21u and 18o anomalies (48-40 Ma) [9, 21]. Studies show that in the Australian sector (Bight Basin) and in the conjugate section along the Antarctic margin, the average spreading rate between anomalies 31 and 27 (68-61 Ma) decreases significantly and is less than 6.0 mm/year with a possible complete cessation of ocean opening [9, 21, 32].

Fig.3. Location of 33o-18o band magnetic anomalies corresponding to the early stage of opening of the south-eastern Indian Ocean in Australia (a) [9] and Antarctica (b) [21, 24]

Based on the gravity field (free air reduction) map obtained from satellite altimetry data [13]

1 – gravity anomaly [21] associated with mantle exhumation; 2 – continent-ocean boundary; 3 – band magnetic anomalies

In Australia, the uplift system is called the Diamantina Zone, which is fairly well studied. The morphology of the oceanic crust in the Diamantina Zone consists of a series of alternating ridges and troughs of sublatitudinal strike length. It is 200 km wide and extends east to 120° E in the eastern part. Most of the ridges represent exposed basement and even in the troughs the sedimentary cover is thin (first hundreds of metres) and fragmentary. The southern boundary of the Diamantina Zone with the Australo-Antarctic Basin is represented by a sharp decrease in depth from 6000-6500 to 4500-5000 m and a change in the morphology of the basement to a less contrasting one [33].

In the Antarctic Davis and Mawson seas, linear rises are not expressed in seafloor relief structures, but are clearly observed on seismic sections and from satellite altimetry data [21]. Large contrasting uplifts of the seafloor basement with amplitudes of up to 2.5 km and more can be traced west of 110° E, where they correspond to a chain of isolated oval gravity field anomalies with amplitudes of 30-40 mGal [21]. The identified uplifts are amagmatic segments of palaeoridges composed of gabbro and/or serpentinised peridotites to varying degrees [21, 33]. These rocks were dredged in the eastern part of the Diamantina fault zone [33].

Based on the analysis of magnetic anomalies in the area of the amagmatic rises, extremely low (less than 1.0 mm/year) rates of ultra-slow spreading are assumed. Along both the Antarctic and Australian continental margins, the two chains of amagmatic palaeoridges begin at the convergence of 31 and 27 magnetic anomalies. This has allowed us to suggest that their formation is associated with the critical drop in spreading velocities at 68-61 Ma [9]. The possibility of the formation of such bottom relief structures as a result of a temporary cessation of ocean spreading has been confirmed experimentally [32].

The linearity of the magnetic anomalies is broken in some places, which is probably related to an in-sufficiently dense observing system and/or a complex, unstable opening of the ocean resulting in jumping of the mid-ocean ridge axes or temporary stopping of spreading [9, 21, 30]. The instability of the open-ing was suggested in a number of papers [9, 20] and later confirmed experimentally [32]. After the 18 magnetic anomaly, the modern stable and symmetric ocean spreading was established, operating in a me-dium-rate opening regime – about 40 mm/year [9, 30].

In Aptian-Albian time, rifting faults (later transformed into oceanic spreading axes) were laid on the thinnest and weakest parts of the lithosphere from the Pacific Ocean side within the Australo-Antarctic continent [33], enveloping the stronger terranes of the continental crust. The processes of rifting and subsequent ocean opening generally moved to the northwest – from the Pacific Ocean deep into the Australo-Antarctic continent [34].

North of Tasmania, the Otway and Gippsland basins opened towards each other and experienced two phases of rift extension at 115-100 and 91-80 Ma [35]. The opening of the Gippsland and Otway basins started the separation of the Tasmanian block from Australia in the Bass Strait, but the continental crustal break-up in the Bass Strait never occurred [35]. About 80 Ma, the Sorell Rift Basin began to form west of Tasmania [13]. Compressional and torsional deformation has been interpreted in Palaeogene sediments on the abyssal in the Sorell Basin [35].

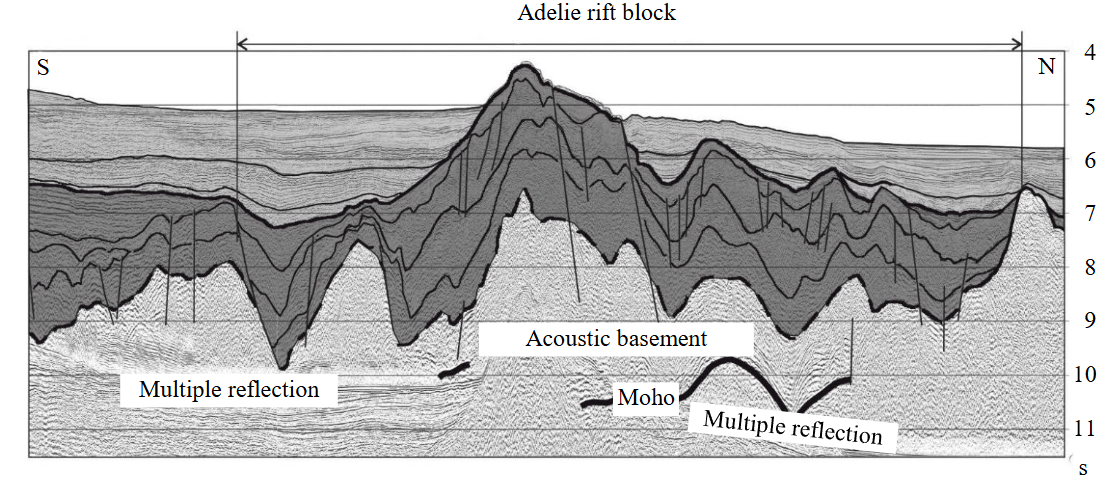

In the Late Cretaceous, the Adelie Block was adjacent to the Sorell Basin to the west, which is now part of the East Antarctic rift margin. The Adelie Block is separated from Antarctica by a rift branch that was actively developed during the 82-67 Ma interval. The basement of this block has been strongly altered by extension, mantle intrusion and basic magmatism, and the lower structural floor of the Adelie Block sedimentary cover has been folded (Fig.4) [21, 36-38]. The separation of the Adélie Block from the East Antarctic continental margin probably occurred as a result of the jumping of the crustal extensional focus (rift axis) from south to north during the Palaeocene. Later, the oceanic space between Tasmania and Antarctica began to open along this new direction about 44 Ma ago [2, 37].

Methods

Palaeoreconstructions of Australia and Antarctica were made using GPlates lithospheric plate tectonics software, which allows modelling of palaeogeographic features in the geologic past [39]. Magnetic anomalies [9] for the Australian margin and [24] for the Antarctic margin were used as input data. The rigid plate model underlying the reconstruction method in the GPlates software does not allow us to obtain a reliable configuration of the Australo-Antarctic palaeocontinent for ages older than 80 Ma. As mentioned above, the problem is the mismatch of geological and geophysical information in the western and eastern parts of the Australo-Antarctic Palaeoplate and the presence of a false broad continental crustal gap in the central part. In this respect, the comparison of Australia and Antarctica in the geological past has been based primarily on the coincidence of the same age conjugate band magnetic anomalies of oceanic origin, whose geometry has not changed significantly since their formation. In the present study, reconstructions were made for the period from 33 anomalies (the onset of ocean spread-ing) to 18 anomalies (the transition to the present mode of spreading).

Results and discussion

Reconstructions of the break-up of Australia and Antarctica have been compiled for the bounda-ries of 79 Ma (chron 33o), 68-61 Ma (chrons 31u-27o), 48 Ma (chron 21), 44 Ma (chron 20) and 40 Ma (chron 18), reflecting the major stages of the early opening of the southeastern Indian Ocean.

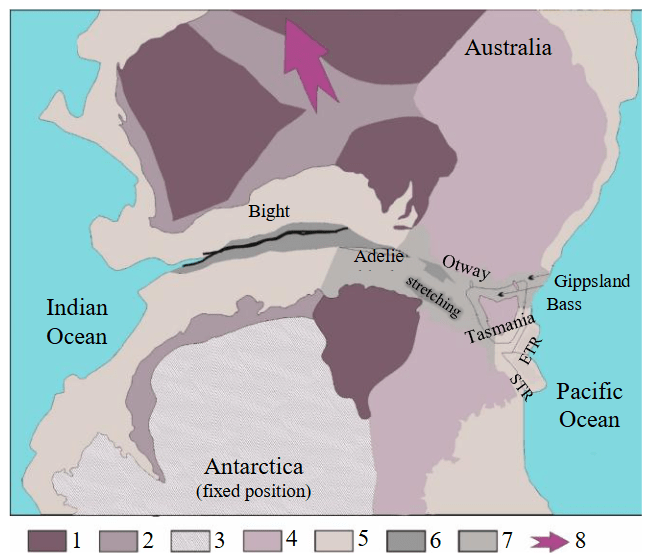

The 33o spreading anomaly is the oldest in the eastern Indian Ocean between Australia and Antarctica. The coincidence of the conjugate 33o anomalies (Fig.5) requires a 2° clockwise rotation of Australia relative to the modern orientation of the continent (the position and orientation of Antarctica remained unchanged in the construction of the palaeoreconstructions).

In the western part of the forming ocean, a space is observed between the conjugate continent-ocean boundaries. This space between the continental margin and the 33o anomaly is composed of serpentinised peridotites formed by exhumation of the upper mantle of the rifting continent.

In the eastern part of the Australo-Antarctic continent, oceanic opening had not yet begun 79 Ma ago. This area is composed of continental crust that is undergoing intense stretching. To align the conjugate continent-ocean boundaries between Tasmania and southeastern Australia on the one hand, and Adelie Land and George V Land on the other, the continental blocks were rotated and shifted.

Fig.4. Seismic profile through the Adelie rift block with deformed lower structural stage of the sedimentary cover (after [21, 36], with additions). The position of the profile is shown in Fig.1

Fig.5. Palaeoreconstruction of Australia – Antarctica by 33 magnetic anomalies (79 Ma)

1 – Archean cratons; 2 – Proterozoic orogens; 3 – undissected Precambrian continental crust; 4 – Late Proterozoic-Palaeozoic orogens; 5 – continental margin; 6 – exhumed mantle of serpentinised peridotites; 7 – continental margin undergoing stretching; 8 – direction of drift of Australia away from Antarctica

Tasmania was rotated 10° counterclockwise and shifted north towards Australia, reducing the width of the present-day Bass Strait by a factor of 3. By the Late Cretaceous (about 79 Ma), the Otway and Gippsland rift basins had already formed north of Tasmania, but the Bass Basin was still opening. The reconstruction shows an overlap of the conjugate continent-ocean boundaries along the western margin of Tasmania. This overlap can be explained by the fact that the Sorell rift basin, whose continental crust will be subject to strong extension, is still in its early stages of formation along the western margin of Tasmania.

The Adélie rift block on the continental margin of George V Land at 79 Ma was still part of the normal or weakly stretched continental crust of Antarctica [21, 37], so in the reconstruction it was rotated clockwise by 7° and its width was reduced by 40 % relative to the modern one.

By around 79 million years ago, Australia had rotated 3-4° anticlockwise and moved slightly north-northwest relative to its position. The pole of rotation was located in the Indian Ocean, near the Kerguelen hotspot. Continental stretching continued in the eastern part of the still coupled Australia and Antarctica.

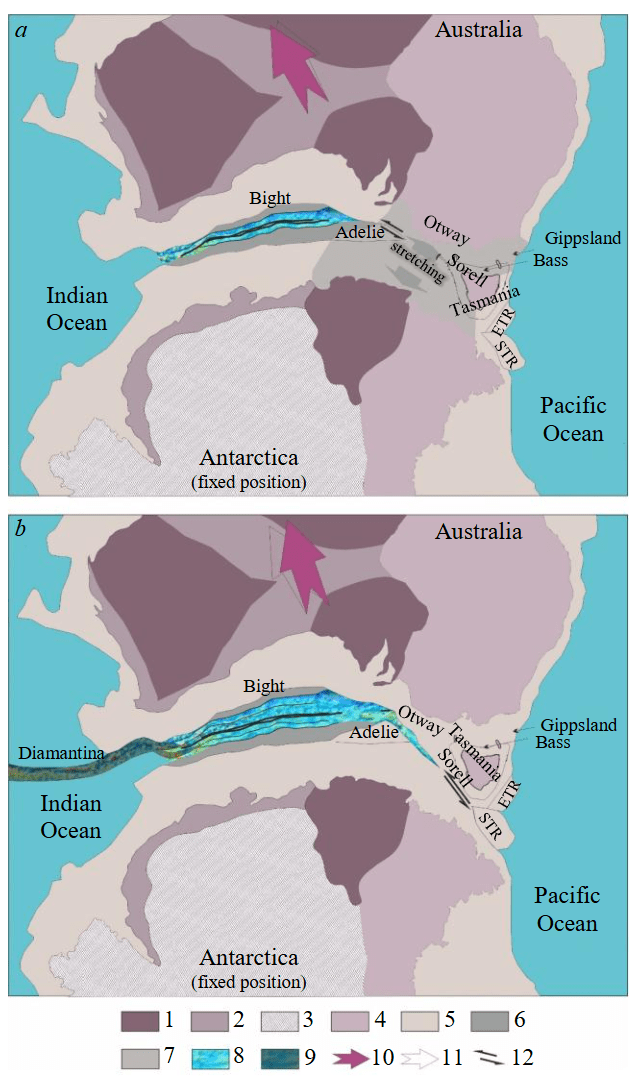

From its position at 79 Ma, Tasmania underwent a 4° clockwise rotation and moved away from southeastern Australia through the opening of the Bass Rift Basin. By 68-61 Ma (chrons 31o-27u, Fig.6, а), the stretching of the continental crust was virtually complete and the Adelie block was in a position almost identical to its present one, but under local transpression stress associated with the north-northeastward drift of Australia.

Fig.6. Palaeoreconstruction of Australia – Antarctica: a – by 31-27 magnetic anomalies (68-61 Ma); b – by 21 magnetic anomalies (48 Ma)

1 – Archean cratons; 2 – Proterozoic orogens; 3 – undissected Precambrian continental crust; 4 – Early Proterozoic-Palaeozoic orogens; 5 – continental margin; 6 – exhumed mantle composed of serpentinised peridotites; 7 – continental margin during extension; 8 – newly formed oceanic crust of the Indian Ocean; 9 – amagmatic rises composed of serpentinised peridotites; 10 – direction of Australia's drift relative to Antarctica; 11 – direction of Australia's drift relative to Antarctica in the previous reconstruction; 12 – left-lateral shear

At the turn of 48 Ma (chron 21u, Fig.6, b), most of the oceanic crust of the early ocean opening between Australia and Antarctica was formed. The Diamantina amagmatic rise zone (along the Australian margin) and its associated unnamed analogue (along the Antarctic margin) formed around this time. Compared to the previous reconstruction (61 Ma), Australia expe-rienced a 4° counterclockwise rotation and continued to move away from Antarctica. The spreading axis advances from northwest to southeast towards the Pacific Ocean. The pole of opening is between Tasmania and Antarctica. The onset of ocean spreading between Antarctica and Tasmania is indirectly indicated by seismic profiling data (see Fig.4) – in the sedimentary cover of the Adelie Block, deformation of the lower part of the post-rift sediments has stopped, which can be explained by the cessation of local transpression in conditions of regional shear between Australia and Antarctica. Tasmania and the Adelie Block assumed their present positions and spatial orientations relative to their parent continents.

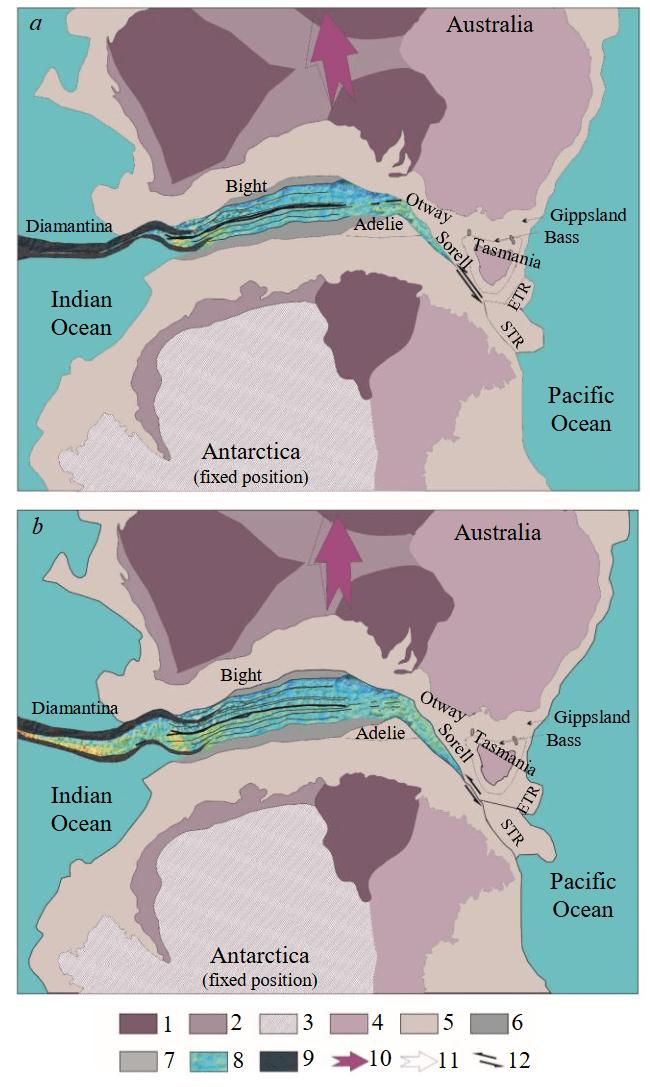

In the mid-Eocene (about 44 Ma, chron 20o, Fig.7, а), the spreading axis continues to move eastwards, but the final separation of Australia (Tasmania) and Antarctica has not yet occurred and there is still a bridge of stretched continental crust between them.

Compared to its position 48 million years ago, Australia has rotated 2° clockwise and the direction of its migration has changed to the north. The change in the direction of Australia's movement is related to the fact that, from 48 Ma, the character of the oceanic space opening between Australia and Antarctica began to be influenced by the young eastern segment of the Indian Ocean.

At 40 Ma (chron 18o, Fig.7, b), the early stage of spreading between Australia and Antarctica, characterized by an unstable mode of oceanic space opening and ultra-slow spreading rates, ended. After 40 Ma, the eastern Indian Ocean opened with moderate spreading rates along the entire length of the conjugate continental margins. At this time, an oceanic strait formed between southwest Tasmania and Antarctica (George V Land).

Fig.7. Palaeoreconstruction of Australia – Antarctica: a – by 20o magnetic anomaly (44 Ma); b – by 18o magnetic anomaly (40 Ma)

See the legend in Fig.6

Conclusion

As a result of these studies, it has been possible to clarify the history of the expansion of the ocean floor between Australia and Antarctica. The formation of the earliest oceanic crust began about 80 million years ago. At that time, ultra-slow seafloor spreading developed in the western part of the opening segment of the Indian Ocean, at a time when a significant part of the eastern region of the Australo-Antarctic Palaeoplate (between modern Tasmania and George V Land) was a single (undivided) massif of continental crust. The pole of ocean opening in the period 80-50 Ma was to the west, in the area of the southern part of the Kerguelen Plateau, and Australia was moving northwestwards relative to Antarctica. At this time, in the eastern part of the Australo-Antarctic continent, the continental crust was undergoing rifting extension, the rift axis south of the Adélie rift block was extinguished, and a left-lateral shear was formed between Tasmania and the conjugate Antarctic continental margin at about 65 Ma.

Between 80 and 48 million years ago, when Tasmania and Antarctica were still coupled, ultra-slow sea-floor spreading (20-26 mm/year) occurred in the west. A critical drop in the spreading rate between 68 and 61 Ma (C31-27) led to the formation of amagmatic ridges composed of serpentinized peridotites (the Diamantine Zone and its conjugate analogue in Antarctica). This event coincided with the extinction of the active rift axis to the south of the Adelie Block and the formation of a left-lateral shear zone between Tasmania and Antarctica.

Around 48 Ma (polarity chron 21), the oceanic rifting rate increased to 40 mm/year (slow spreading mode). During 48-40 Ma (polarity chrons C21, C20, and C18), the oceanic rift continued to advance eastward (from the Indian Ocean side) and northwestward (from the Pacific Ocean side), although the break-up of Australia (Tasmania) and Antarctica was not yet complete. The pole of opening at this time was near the southern edge of Tasmania and was moving further southeast towards the Pacific Ocean. The change in the direction of motion of Australia relative to Antarctica from north-northwest to northward resulted in a change in the geometry of the opening of the southeastern Indian Ocean. The slow spreading of the early stage of opening of the southeastern part of the Indian Ocean ended 40 Ma (polarity chron C18) with the transition to the present stable regime of ocean opening times (70 mm/year).

References

- Aitken A.R.A., Young, D.A., Ferraccioli F. et al. The subglacial geology of Wilkes Land, East Antarctica. Geophysical Research Letters. 2014. Vol. 41. Iss. 7, p. 2390-2400. DOI: 10.1002/2014GL059405

- Norvick M.S., Smith M.A. Mapping the plate tectonic reconstruction of Southern and Southeastern Australia and implications for petroleum systems. The APPEA Journal. 2001. Vol. 41, p. 15-35. DOI: 10.1071/AJ00001

- Williams S.E., Whittaker J.M., Müller R.D. Full-fit, palinspastic reconstruction of the conjugate Australian-Antarctic margins. Tectonics. 2011. Vol. 30. Iss. 6. N TC6012. DOI: 10.1029/2011TC002912

- Williams S.E., Whittaker J.M., Halpin J.A., Müller R.D. Australian-Antarctic breakup and seafloor spreading: Balancing geological and geophysical constraints. Earth-Science Reviews. 2019. Vol. 188, p. 41-58. DOI: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2018.10.011

- Powell C.McA., Roots S.R., Veevers J.J. Pre-breakup continental extension in East Gondwanaland and the early opening of the eastern Indian Ocean. Tectonophysics. 1988. Vol. 155. Iss. 1-4, p. 261-283. DOI: 10.1016/0040-1951(88)90269-7

- Royer J.-Y., Sandwell D.T. Evolution of the eastern Indian Ocean since the Late Cretaceous: Constraints from Geosat altimetry. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth. 1989. Vol. 94. Iss. B10, p. 13755-13782. DOI: 10.1029/JB094iB10p13755

- Glen R.A. The Tasmanides of eastern Australia. Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 2005. Vol. 246, p. 23-96. DOI: 10.1144/GSL.SP.2005.246.01.02

- Ball P., Eagles G., Ebinger C. et al. The spatial and temporal evolution of strain during the separation of Australia and Antarctica. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems. 2013. Vol. 14. Iss. 8, p. 2771-2799. DOI: 10.1002/ggge.20160

- Tikku A.A., Cande S.C. The oldest magnetic anomalies in the Australian-Antarctic Basin: Are they isochrons? Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth. 1999. Vol. 104. Iss. B1, p. 661-677. DOI: 10.1029/1998JB900034

- Whittaker J.M., Williams S.E., Müller R.D. Revised tectonic evolution of the Eastern Indian Ocean. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems. 2013. Vol. 14. Iss. 6, p. 1891-1909. DOI: 10.1002/ggge.20120

- Close D.I., Watts A.B., Stagg H.M.J. A marine geophysical study of the Wilkes Land rifted continental margin, Antarctica. Geophysical Journal International. 2009. Vol. 177. Iss. 2, p. 430-450. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-246X.2008.04066.x

- Halpin J.A., Daczko N.R., Direen N.G. et al. Provenance of rifted continental crust at the nexus of East Gondwana breakup. Lithos. 2020. Vol. 354-355. N 105363. DOI: 10.1016/j.lithos.2019.105363

- Sandwell D.T., Müller R.D., Smith W.H.F. et al. New global marine gravity model from CryoSat-2 and Jason-1 reveals buried tectonic structure. Science. 2014. Vol. 346. Iss. 6205, p. 65-67. DOI: 10.1126/science.1258213

- Tooze S., Halpin J.A., Noble T.L. et al. Scratching the Surface: A Marine Sediment Provenance Record From the Continental Slope of Central Wilkes Land, East Antarctica. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems. 2020. Vol. 21. Iss. 11. N e2020GC009156. DOI: 10.1029/2020GC009156

- Sauermilch I., Whittaker J.M., Bijl P.K. et al. Tectonic, Oceanographic, and Climatic Controls on the Cretaceous-Cenozoic Sedimentary Record of the Australian-Antarctic Basin. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth. 2019. Vol. 124. Iss. 8, p. 7699-7724. DOI: 10.1029/2018JB016683

- Sergeeva V.M., Leitchenkov G.L., Dubinin E.P., Groholsky A.L. Experimental Simulation of Conditions of the Tasmania and Adélie Continental Blocks Formation at the Early Stage of the Break-Up of the Australian-Antarctic Paleocontinent. Geotectonics. 2020. Vol. 54. N 6, p. 741-753. DOI: 10.1134/S0016852120060138

- Espurt N., Callot J.-P., Roure F. et al. Transition from symmetry to asymmetry during continental rifting: an example from the Bight Basin–Terre Adélie (Australian and Antarctic conjugate margins). Terra Nova. 2012. Vol. 24. Iss. 3. P. 167-180. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-3121.2011.01055.x

- Boger S.D. Antarctica – Before and after Gondwana. Gondwana Research. 2011. Vol. 19. Iss. 2, p. 335-371. DOI: 10.1016/j.gr.2010.09.003

- Maritati A., Halpin J.A., Whittaker J.M., Daczko N.R. Fingerprinting Proterozoic Bedrock in Interior Wilkes Land, East Antarctica. Scientific Report. 2019. Vol. 9. N 10192. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-019-46612-y

- Sayers J., Symonds P.A., Direen N.G., Bernardel G. Nature of the continent-ocean transition on the non-volcanic rifted margin of the central Great Australian Bight. Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 2001. Vol. 187, p. 51-76. DOI: 10.1144/GSL.SP.2001.187.01.04

- Leitchenkov G.L., Guseva Yu.B., Gandyukhin V.V. et al. Structure of the Earth’s Crust and Tectonic Evolution History of the Southern Indian Ocean (Antarctica). Geotectonics. 2014. Vol. 48. N 1, p. 5-23. DOI: 10.1134/S001685211401004X

- Gillard M., Autin J., Manatschal G. et al. Tectonomagmatic evolution of the final stages of rifting along the deep conjugate Australian-Antarctic magma-poor rifted margins: Constraints from seismic observations. Tectonics. 2015. Vol. 34. Iss. 4, p. 753-783. DOI: 10.1002/2015TC003850

- Direen N.G., Borissova I., Stagg H.M.J. et al. Nature of the continent–ocean transition zone along the southern Australian continental margin: a comparison of the Naturaliste Plateau, SW Australia, and the central Great Australian Bight sectors. Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 2007. Vol. 282, p. 239-263. DOI: 10.1144/SP282.12

- Leitchenkov G.L., Grikurov G.E. The Tectonic Structure of the Antarctic. Geotectonics. 2023. Vol. 57. Suppl. 1, p. S28-S33. DOI: 10.1134/s0016852123070087

- Larter R.D., Barker P.F. Effects of ridge crest-trench interaction on Antarctic-Phoenix Spreading: Forces on a young subducting plate. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth. 1991. Vol. 96. Iss. B12, p. 19583-19607. DOI: 10.1029/91JB02053

- Seebeck H., Strogen D.P., Nicol A. et al. A tectonic reconstruction model for Aotearoa-New Zealand from the mid-Late Cretaceous to the present day. New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics. 2024. Vol. 67. Iss. 4, p. 527-550. DOI: 10.1080/00288306.2023.2239175

- Gardner R.L., Daczko N.R., Halpin J.A., Whittaker J.M. Discovery of a microcontinent (Gulden Draak Knoll) offshore Western Australia: Implications for East Gondwana reconstructions. Gondwana Research. 2015. Vol. 28. Iss. 3, p. 1019-1031. DOI: 10.1016/j.gr.2014.08.013

- Gibson G.M., Totterdell J.M., White L.T. et al. Pre-existing basement structure and its influence on continental rifting and fracture zone development along Australia’s southern rifted margin. Journal of the Geological Society. 2013. Vol. 170. N 2, p. 365-377. DOI: 10.1144/jgs2012-040

- Eagles G., Gohl K., Larter R.D. High-resolution animated tectonic reconstruction of the South Pacific and West Antarctic Margin. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems. 2004. Vol. 5. Iss. 7. N Q07002. DOI: 10.1029/2003GC000657

- Golynsky A.V., Ivanov S.V., Kazankov A.Ju. et al. New continental margin magnetic anomalies of East Antarctica. Tectonophysics. 2013. Vol. 585, p. 172-184. DOI: 10.1016/j.tecto.2012.06.043

- Bronner A., Sauter D., Manatschal G. et al. Magmatic breakup as an explanation for magnetic anomalies at magma-poor rifted margins. Nature Geoscience. 2011. Vol. 4. Iss. 8, p. 549-553. DOI: 10.1038/ngeo1201

- Dubinin E.P., Leitchenkov G.L., Grokholsky A.L. et al. Structure-Forming Peculiarities at the Early Stage of Antarctic–Australia Separation Based on Physical Modeling. Izvestiya, Physics of the Solid Earth. 2019. Vol. 55. N 2, p. 256-269. DOI: 10.1134/S1069351319020022

- Beslier M.-O., Royer J.-Y., Girardeau J. et al. A wide ocean-continent transition along the south-west Australian margin: first results of the MARGAU/MD110 cruise. Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France. 2004. Vol. 175. N 6, p. 629-641. DOI: 10.2113/175.6.629

- Vérard C., Stampfli G.M. Geodynamic Reconstructions of the Australides–2: Mesozoic–Cainozoic. Geosciences. 2013. Vol. 3. Iss. 2, p. 331-353. DOI: 10.3390/geosciences3020331

- Stickley C.E., Brinkhuis H., Schellenberg S.A. et al. Timing and nature of the deepening of the Tasmanian Gateway. Paleoceanography. 2004. Vol. 19. Iss. 4. N PA4027. DOI: 10.1029/2004PA001022

- Varova L.V., Leichenkov G.L., Guseva Yu.B. Tectonic structure of the continental margin of the Adelie Land – George V Land and the adjacent abyssal basin (East Antarctica). Problemy Arktiki i Antarktiki. 2011. N 2 (88), p. 69-80.

- McCarthy A., Falloon T.J., Sauermilch I. et al. Revisiting the Australian-Antarctic Ocean-Continent Transition Zone Using Petrological and Geophysical Characterization of Exhumed Subcontinental Mantle. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems. 2020. Vol. 21. Iss. 7. N e2020GC009040. DOI: 10.1029/2020GC009040

- Tauxe L., Stickley C.E., Sugisaki S. et al. Chronostratigraphic framework for the IODP Expedition 318 cores from the Wilkes Land Margin: Constraints for paleoceanographic reconstruction. Paleoceanography. 2012. Vol. 27. Iss. 2. N PA2214. DOI: 10.1029/2012PA002308

- Müller R.D., Cannon J., Xiaodong Qin et al. GPlates: Building a Virtual Earth Through Deep Time. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems. 2018. Vol. 19. Iss. 7, p. 2243-2261. DOI: 10.1029/2018GC007584