Geodynamic processes, Cenozoic rifting and the mechanism of formation of the deepest depressions on land in Antarctica

- 1 — Ph.D. Leading Researcher Schmidt Institute of Physics of the Earth, RAS ▪ Orcid

- 2 — Ph.D., Dr.Sci. Head of Laboratory Shirshov Institute of Oceanology, RAS ▪ Orcid ▪ Elibrary ▪ Scopus ▪ ResearcherID

Abstract

New geophysical data have revealed a large number of narrow and deep depressions in the ice sheet bed in various areas of Antarctica with depths of up to 3500 m below sea level (Denman Depression). These depressions have all the features of Cenozoic rifting – steep sides, the greatest depths on land, strong negative gravity anomalies in free air (–100 mGal and less) and high heat flow. The continuation of rifting after the glaciation of Antarctica with almost complete cessation of sedimentation under the ice explains the great depth and steep sides of the depressions with increased heat flow and mass deficit. Important features of the coastal depressions of the ice bed are their retrograde slopes, characteristic only of Antarctica. The subglacial relief of the basins on the approach to the continental coast sharply flattens out, which indicates sedimentation in the transition zone during periods of ice melting and subsequent marine regressions-transgressions in the Late Cenozoic. Increased heat flow can lead to melting of the glacier base and promote their accelerated sliding from the bedrock into the ocean. Another factor affecting the rate of glacier sliding into the ocean is the friction force with the bedrock. The presence of soft young sediments reduces friction and promotes the sliding of ice sheets into the ocean under the influence of gravity. Fast-moving ice sheets in Antarctica are mainly confined to areas of rift basins. Acceleration of glacier runoff along retrograde slopes into the ocean has a positive feedback and creates a potential hazard of global sea level rise. The geodynamic mechanism responsible for the Cenozoic activation of Antarctic rift zones is due to the action of local upper mantle plumes beneath Antarctica during and after the breakup of Gondwana. Further reactivation of extension along weakened zones in the lithosphere is associated with the general acceleration of global mantle convection that began in the Miocene. Numerical three-dimensional geodynamic models of the formation of the Transantarctic Mountains and the uplift of the Gamburtsev intraplate orogen in the Cenozoic are proposed.

Funding

The study was carried out partly under the State assignment of the Shirshov Institute of Oceanology, RAS, N FMWE-2021-0004; partly under the State assignment of the Schmidt Institute of Physics of the Earth, RAS.

Introduction

The Antarctic continental block consists of terranes of varying ages, origins, and geological compositions and is surrounded by the oceanic lithosphere, mainly formed along mid-ocean rift zones [1]. The Antarctic Plate borders six other plates, mostly in the southern hemisphere. The Antarctic continent, which extends over an area 14×106 km2, is almost completely covered by glaciers (about 99 %) with a maximum thickness of 4.6 km and an average thickness of 1.94 km [2].

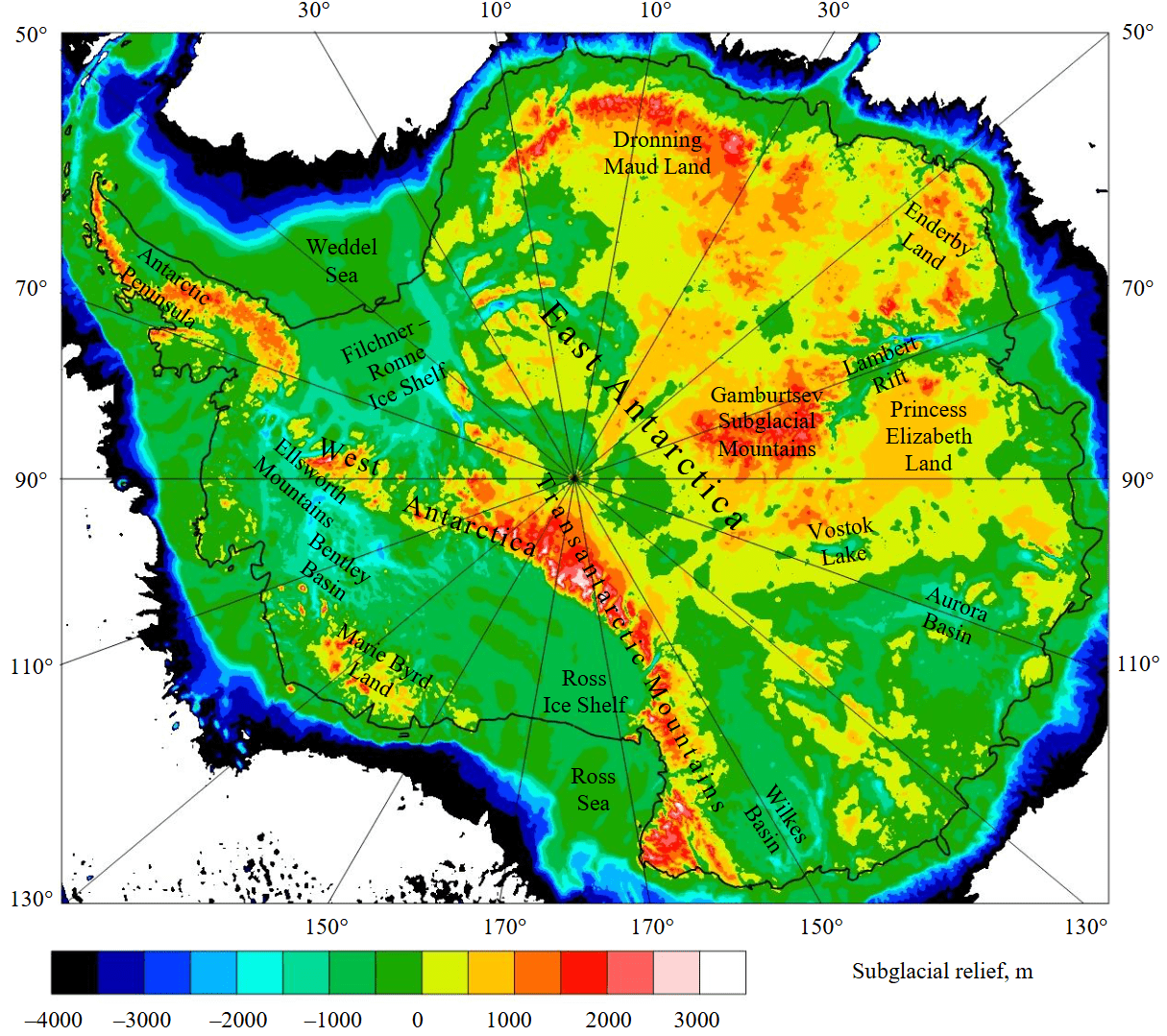

A complex subglacial relief was revealed, which changes from –3.5 to 4 km [2]. The maximum topographic heights reach 4.9 km (Mount Vinson, Ellsworth Mountains, West Antarctica, Fig.1). The BedMachine subglacial relief model [2] discovered subglacial depressions of bedrock relief in West and East Antarctica, lying below sea level, with depths of 1-2 km and more.

According to the model, the Denman Depression in East Antarctica, 3500 m below sea level, is the deepest of those discovered. Its depth is greater than that of Lake Baikal, the Caspian Sea, Tanganyika, and intracontinental depressions on other continents that are not filled with water. Other depressions in different areas of Antarctica also have depths of 2000 m or more. This paper studies the geodynamic processes in deep subglacial depressions in Antarctica and the mechanism of their formation.

Tectonics and geodynamics of the Antarctic continent

The evolution of Antarctica to its present stage has included geological episodes during the Proterozoic, Paleozoic, Mesozoic, and Cenozoic. The Grunehogna, Napier and Mawson cratons of East Antarctica preserve evidence of tectonic activity since the Archean. Archean rocks are also found in the Prince Charles Mountains, parts of Princess Elizabeth Land, and in Adеlie Land [3]. Antarctica consists of two different regions separated by the Transantarctic Mountains (Fig.1). The geological structure and history of West and East Antarctica differ significantly.

Fig.1. Subglacial relief of Antarctica from BedMachine [2]

West Antarctica consists of several terranes of different origins and ages. The West Antarctic Rift System is a key element of West Antarctica [4, 5] and extends from the Ross Sea to the Antarctic Peninsula. More than 30 subglacial volcanoes have been identified within the system and Holocene volcanic activity has been revealed [6]. An important terrane of West Antarctica is the Filchner – Ronne Ice Shelf between the Ellsworth Mountains, the southern part of the Antarctic Peninsula and the western boundary of East Antarctica. It is believed that this is a failed Mesozoic rift, covered by sediments [7]. Along the Pacific coast, the mountainous Antarctic Peninsula, the mountainous Marie Byrd Land are located successively, and West Antarctica is closed by the Ross Ice Shelf with negative subglacial relief, which is part of the West Antarctic Rift System (Fig.1).

The Moho depth for the West Antarctic Rift System is generally in the range of 16-32 km. Beneath the Ross Ice Shelf, the Moho is about 16-24 km, while beneath the Filchner – Ronne Ice Shelf it is deeper (26-30 km). In the central part of the rift zone beneath the Byrd and Bentley basins, deep subglacial depression is found (to about 2.5 km below sea level), a thick ice sheet of 2-3 km, and a depth to the Moho of about 20-22 km. The Moho in West Antarctica deepens beneath Marie Byrd Land, the Ellsworth Mountains, and the Antarctic Peninsula, where it reaches a maximum depth of about 38 km [3]. West Antarctica has a large number of sedimentary basins: the Ross Basin (2-6 km of sediments), the Filchner – Ronne Basin (2-12 km) with extensions into East Antarctica, the Bentley Trench and the Byrd Basin (2-4 km). The deepest basin, the Filchner – Ronne, has a complex structure with multi-layered sediments [8]. Taking into account sedimentary basins, the maximum stretching of the crust occurred on the margins of the Antarctic continent under the Ross Ice Shelf and the Filchner – Ronne Ice Shelf, where the thickness of the continental crust is only 10-20 km [3]. The lithosphere beneath West Antarctica is also thinned, and beneath it (except the Filchner – Ronne Ice Shelf) the hot upper mantle lies [9, 10].

East Antarctica is a Precambrian superterrane that was part of Gondwana and formerly Rodinia, and includes several Archean cratons [1]. The internal boundaries of the tectonic blocks of East Antarctica are poorly understood due to their remoteness and the fact that the rocks are covered by a thick layer of ice. The boundaries and properties of the tectonic blocks are mainly determined by geophysical fields, subglacial relief, and seismic data. The geology of the coastal areas and rocks is similar to the neighboring continental blocks of Gondwana, in which the coast of Dronning Maud Land bordered the southeastern part of Africa. The Kaapvaal Craton and the surrounding Proterozoic belts have continuations in this part of Antarctica (the Grunehogna Craton and the Proterozoic Maudheim Belt). The coastal tectonic structures of Enderby Land, the Lambert Rift, and Princess Elizabeth Land have a continuation in Hindustan. The rest of the coast of East Antarctica bordered the southern coast of Australia (the Proterozoic belts and the Gawler Craton in South Australia). Correlation of tectonic structures and rocks is present only in the coastal areas. At the same time, intracontinental geological structures such as the Gamburtsev Subglacial Mountains, the Polargap Subglacial Highlands and the Vostok Basin are unique.

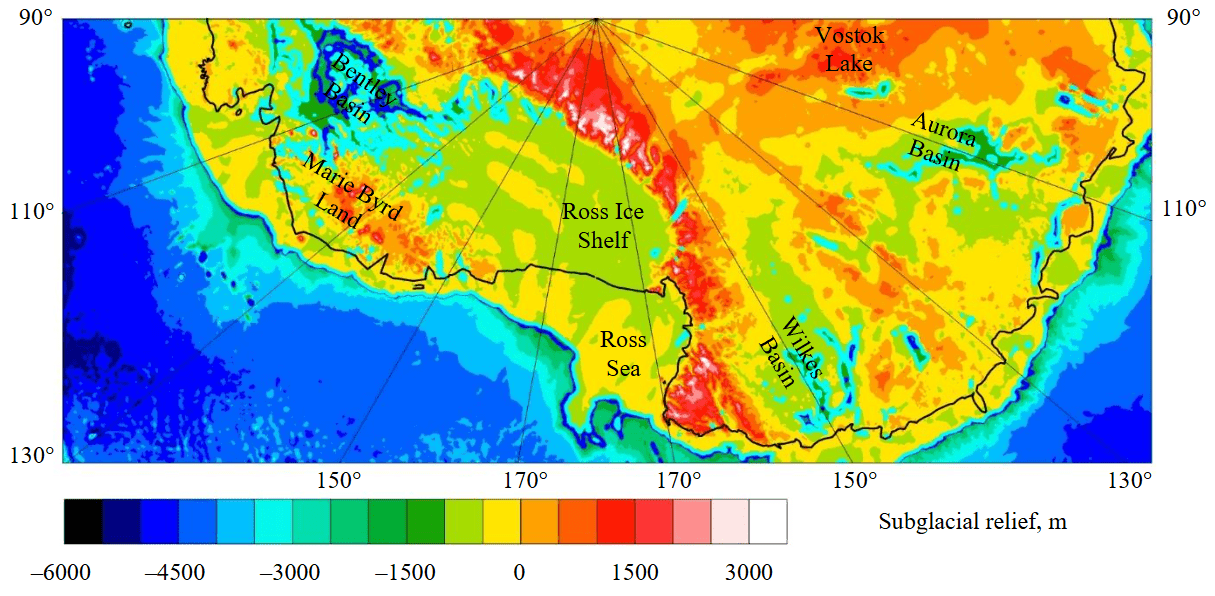

Recently, East Antarctica has been divided by researchers into two parts – the Indo-Antarctic Block with a relatively high subglacial relief and the Australo-Antarctic Block with a low subglacial relief. The Indo-Antarctic Block extends from the western boundary of East Antarctica with the Filchner – Ronne Ice Shelf to Princess Elizabeth Land. The eastern boundary of the Indo-Antarctic Block runs approximately along the axis of Lake Vostok – the Denman Depression (Fig.1, 2). From west to east, the block includes Coats Land on the border with the Filchner – Ronne Ice Shelf (with local mountain ranges and deep subglacial depressions between them). South of Coats Land is the elevated Polargap Subglacial Highlands; to the east is the vast mountainous region of Dronning Maud Land, which passes into Enderby Land. South of Enderby Land the Gamburtsev Subglacial Mountains lie. Enderby Land is separated from Princess Elizabeth Land by the large Lambert Rift, which extends from the coast of Amery hundreds of kilometers south to the Gamburtsev Subglacial Mountains with a possible continuation. The Australo-Antarctic Block includes the subglacial Aurora Basin with continuations to the coast and the Wilkes Basin, bordering the Transantarctic Mountains. This block is characterized by subglacial relief below sea level and a large number of deep intracontinental basins with steep sides (Fig.2). Some of them reach the coast.

Fig.2. Subglacial relief of Australo-Antarctic Block and part of West Antarctica according to BedMachine model [2]

East Antarctica is characterized by Cretaceous and later magmatism [11, 12]. A large number of sedimentary basins with thinned crust have been discovered, especially in the Australo-Antarctic Block [3, 8]. The degree of crustal stretching and magmatic underplating is significantly lower than in West Antarctica. In none of the known seismic sections have the velocities in the lower crust reached 7 km/s, whereas in West Antarctica, in all the obtained seismic profiles, the velocities in the lower crust exceed 7 km/s, which indicates extensive intrusion of mantle material into the crust [3].

The maximum depth to Moho of 56-58 km under the Gamburtsev Subglacial Mountains in East Antarctica confirmed the presence of deep and compact orogenic roots. Another deep Moho in East Antarctica was discovered under the orogens of Dronning Maud Land. The minimum Moho in East Antarctica is under the Lambert Rift (24-28 km). Moho variations under Antarctica are described in more detail in [3, 13]. East Antarctica also contains large sedimentary basins [8], such as the Pensacola Basin (1-2 km of sediments), Coats Land (1-3 km), Dronning Maud Land (1-2 km), Vostok (2-7 km), Aurora (1-3 km), Astrolabe (2-4 km), Adventure (2-4 km), Wilkes (1-4 km), Jutulstraumen (1-2 km), Lambert (2-8 km), Scott, Denman, Vanderford, and Totten (2-4 km).

The initial breakup between Australia, India and Antarctica occurred in the Early Cretaceous. The Late Cretaceous was characterized by a major phase of tectonic extension between East and West Antarctica [11]. Tectonomagmatic processes in West Antarctica were determined by the proximity of the framing subduction zone. The complex tectonic structure of West Antarctica was mainly formed due to compression from subduction on the Pacific margin of Gondwana at the end of the Paleozoic – Mesozoic. At present, a small fragment remains from this subduction at the end of the Antarctic Peninsula. Subsequently, stretching processes shaped the appearance of West Antarctica [4, 5]. The beginning of the opening of the West Antarctic Rift System is closely associated with the uplift and formation of the Transantarctic Mountains in the early Cenozoic.

At the same time, the processes of rifting and magmatism in East Antarctica, located at a considerable distance from the paleosubduction on the Pacific margin of Gondwana, were largely determined by mantle plumes. The heads of the plumes spread under the continental lithosphere when approaching it, causing stretching of the lithosphere. Plumes under this part of Gondwana formed the Karoo magmatic province in South Africa, Maud and Dufek in Antarctica about 180 million years ago, and later, about 130 million years ago, magmatism developed under the influence of the proto-Kerguelen plume [4, 11].

Now, most of the Antarctic Plate with Antarctica in the center is surrounded by mid-ocean ridges where hot upper mantle flows rise. There are also hot spots with lower mantle matter, such as the Kerguelen Plateau. With the emergence of the Drake Passage and the subsequent formation of the cold Antarctic Circumpolar Current in the Eocene, glaciation of Antarctica began (at the boundary of the Eocene and Oligocene). Since then, regressions and transgressions of the sea have occurred in the coastal zone [14].

Deep subglacial depressions as a result of rifting processes in the Cenozoic

On the subglacial relief map (Fig.2) for the West Antarctic Rift System and the Australo-Antarctic Block, the blue contour highlights the depth of 1500 m, and the light blue contour highlights 700 m below sea level. The vast intracontinental Bentley Basin has depths of up to 2500 m, and gravity anomalies in free air reach –60 mGal [15]. At the same time, the Ross Ice Shelf has a moderate subglacial relief, here narrow depressions are practically absent.

There are also several narrow depressions cutting the Transantarctic Mountains, which rapidly flatten out under the Ross Ice Shelf. In the Australo-Antarctic Block of the continent from the Vostok Basin to the Transantarctic Mountains there is a whole system of subglacial grabens in the Aurora Basin with depths of up to 1500 m. Their gravity anomalies in free air are up to –100 mGal, while anomalies of coastal basins can reach –150 mGal [15]. The Vostok Basin is relatively isolated among high subglacial relief and its depths are up to 1400 m, and free-air gravity anomalies reach –80 mGal. Another system of intracontinental subglacial grabens is found in the Wilkes Basin with depths of up to 2000 m reaching the continental coast, where the depth drops rapidly, and free-air anomalies of up to –100 mGal. Isolated Adventure and Astrolabe basins with depths of up to 2000 m and free-air anomalies of up to –100 mGal are found between the Aurora and Wilkes Basin systems [15].

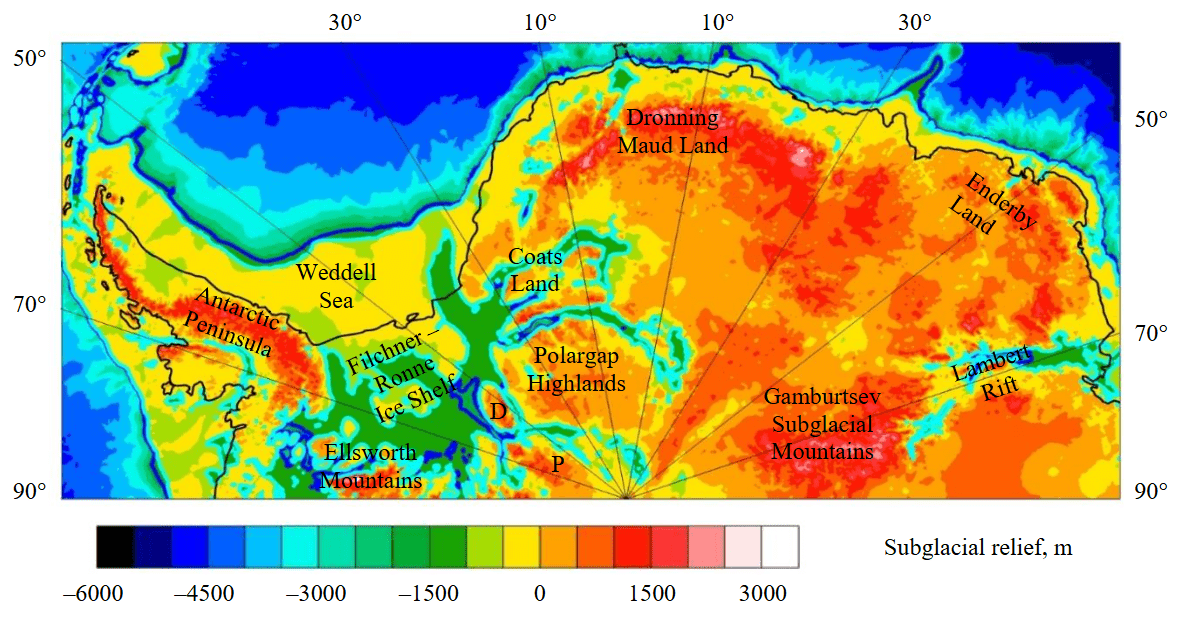

Similarly to Fig.2, the blue contour highlights the depth of 1500 m, and the light blue contour highlights 700 m below sea level (Fig.3). Compared to West Antarctica and the Australo-Antarctic Block, the Indo-Antarctic Block of East Antarctica has a relatively high subglacial relief. The Lambert Rift stands out, penetrating deep into the continent and having depths of 2500 m and more with gravity anomalies in free air up to –100 mGal. The deepest part of the graben is located several hundred kilometers from the coast; as it approaches the coast, its edges widen and the bottom flattens out.

The depths of the Bailey, Slessor, and Recovery depressions on Coats Land on the border with West Antarctica reach 2000 m and more. For them, gravity anomalies in free air are observed from –100 to –160 mGal. Another system of deep basins with similar parameters separates the Pensacola Mountains, the Dufek Block, and the Polargap Subglacial Highlands. These depressions pass into the southern part of the bottom of the Filchner – Ronne Ice Shelf, where their bottom flattens out, and the gravity anomalies decrease several times. An anomalous relief of the bed has been revealed for the Filchner – Ronne Basin bordering East Antarctica. Thus, the bottom of the Weddell Sea shelf is shallower than the subglacial bed of the Filchner – Ronne Ice Shelf.

Fig.3. Subglacial relief of Indo-Antarctic Block of East Antarctica and part of West Antarctica according to BedMachine model [2] D – Dufek Block; P – Pensacola Mountains

Fig.4. Rise and spread of the lower mantle plume for the three-dimensional model of Kotelkin and Lobkovsky [18], modified

Methods

At the first stage, the formation of Antarctica rifts was associated with the processes of stretching and breakup of the Gondwana. The pulling forces of the subduction zone surrounding Gondwana acted along its edges. At the same time, mantle plumes were located under the supercontinent itself [16, 17]. Plume heads spread under the continental lithosphere when approaching the surface, causing it to thin and rupture, forming smaller continental blocks. The breakup of a supercontinent usually occurs along weakened zones of the continental lithosphere at the boundaries of tectonic blocks. This can also be the activation of old rifts.

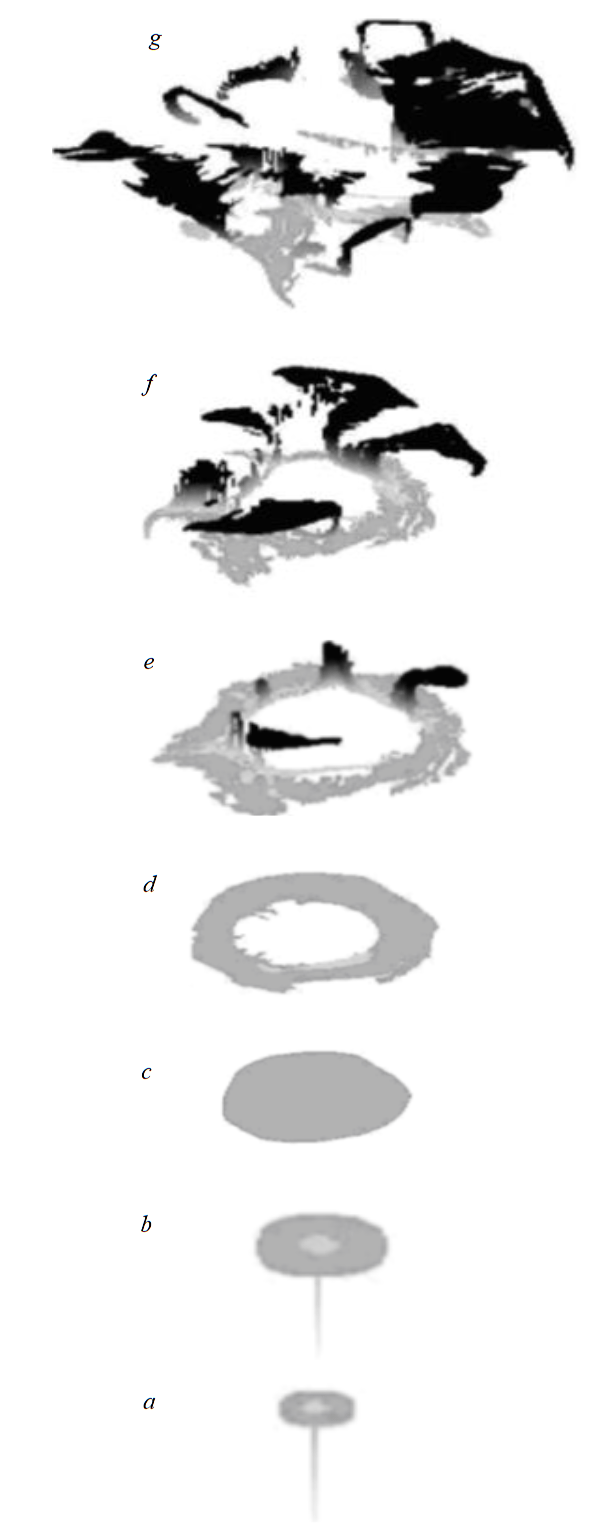

The mechanism of the rise of the lower mantle superplume and its fragmentation into upper mantle plumes is described in detail in the model of Kotelkin and Lobkovsky [18]. Figure 4 shows the main stages of the spreading of hot matter from the lower mantle plume under the phase boundary at a depth of 660 km and the subsequent penetration into the upper mantle. The material with low density floats upward (Fig.4, a, b). Next, the light plume material spreads and transitions to a ring shape (Fig.4, c, d). The moment of the breakthrough of the hot plume material of the phase boundary and the formation of a group of upper mantle plumes (shown in black) is visible on Fig.4, e. Figure 4, f, g shows the subsequent rise of hot material in the upper mantle and its spreading under the lithosphere.

The stages in Fig.4, f, g correspond to the current state of Antarctica. It is assumed that the initial lower mantle plume was proto-Kerguelen plume [19], which has now shifted north of Antarctica to the southern Indian Ocean [20]. The ring structure of hot material as the plume approaches the surface correlates with the submeridional rifts of East Antarctica [21]. The formation of such structures may be associated with the formation of upper mantle convective cells from the lower mantle proto-Kerguelen plume that arose beneath Gondwana [22].

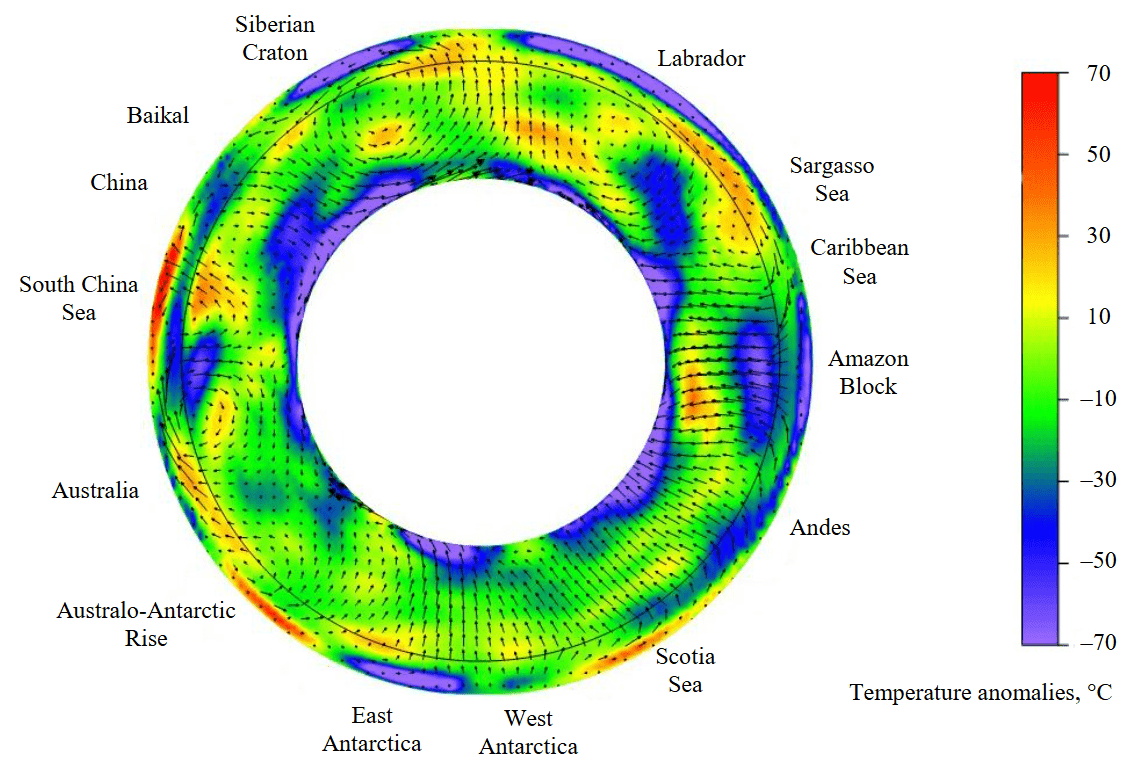

In this study, based on the global seismic tomography model SMEAN2 [23] and non-Newtonian rheology, an instantaneous spherical model of the modern Earth with plate rheology was numerically calculated using a modified CitcomS program. The influence of a large amount of water in bound form at the bottom of the upper mantle and in the transition zone is taken into account [24, 25]. The presence of water leads to a significant decrease in the effective viscosity in this area. The model and numerical scheme are described in detail in [10]. In the global transmeridional section of the Earth at 110 and 290 deg E, descending mantle flows predominate (Fig.5). Under East Antarctica, a vast area with a positive temperature anomaly has been identified in the upper mantle.

Fig.5. Temperature anomalies and flow velocities in the Earth’s mantle (section at 110 and 290 deg E).

The black circle shows the boundary between the upper and lower mantle at a depth of 660 km

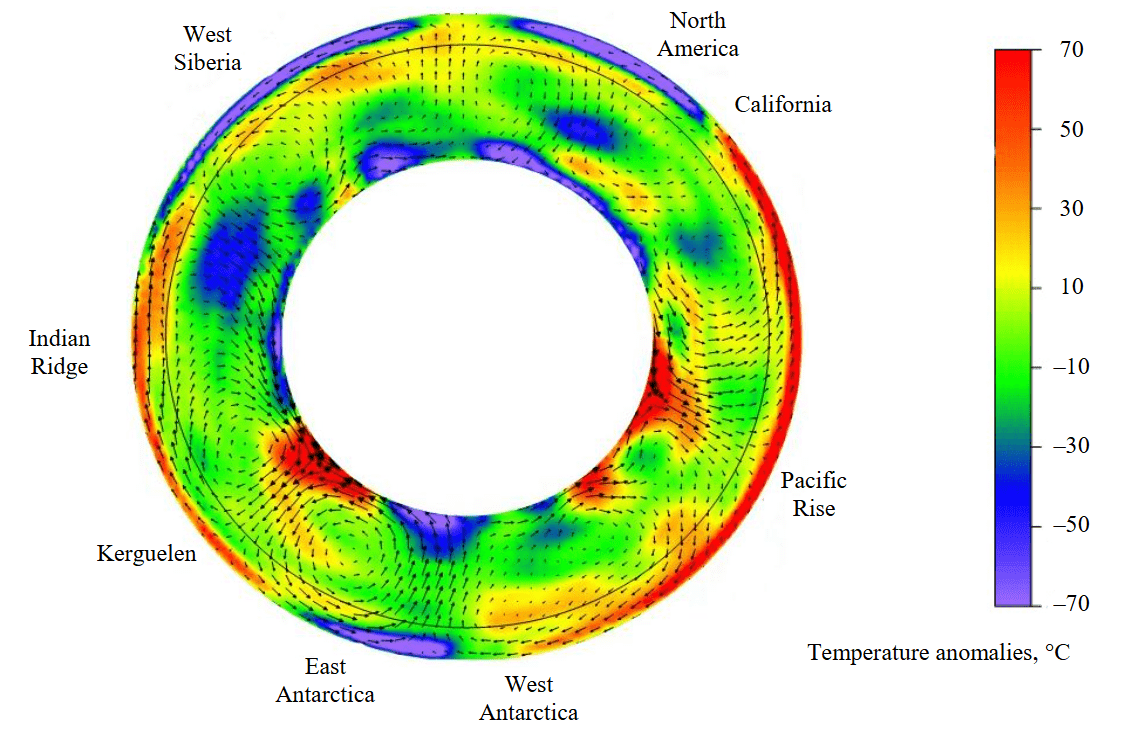

Figure 6 shows the temperature anomalies and flow velocities in the mantle (a spherical transmeridional section of the Earth at 70 and 250 deg E). Hot mantle material is carried under East Antarctica by subhorizontal mantle flows from the African superplume. Further under East Antarctica in the Gamburtsev Mountains area there is a descending mantle flow that closes the convection cell. Similarly, for West Antarctica, hot material is carried by subhorizontal mantle flows from the Pacific superplume, and the cell again closes on the descending flow under the Gamburtsev Mountains. Hot material moves subhorizontally in the upper mantle of West Antarctica towards the South Pole rests against the thick cold lithosphere of East Antarctica (Fig.6). Here part of mantle material floats up, causing the edge of East Antarctica to rise and the formation of the non-collisional Transantarctic Mountains, which lie on the border between West and East Antarctica (see Fig.1). At the same time, both lower mantle plumes (African and Pacific) are located significantly further north. Figures 5 and 6, show the modern distribution of temperature anomalies and the flow velocities, whereas Fig.4 shows possible evolution of the lower mantle plume beneath Gondwana.

Fig.6. Temperature anomalies and flow velocities in the Earth’s mantle (section at 70 and 250 deg E). The black circle shows the boundary between the upper and lower mantle at a depth of 660 km

Tectonomagmatic processes in West Antarctica are associated with framing paleosubduction and are characterized by modern subglacial volcanism of both subduction and plume origin [26]. For the rift systems of West Antarctica (under the Filchner – Ronne Ice Shelf) and the neighboring part of East Antarctica (Coats Land, Slessor and Recovery depressions) that are more distant from the Pacific coast, the mechanism of the return upper mantle cell could have been at work [27]. Subduction along the Pacific margin of West Antarctica and off the coast of the Antarctic Peninsula generated a return cell with mantle upwellings beneath central West Antarctica, as well as at the boundary with East Antarctica in the area of the Slessor Glacier basins and adjacent regions at a distance of about 2000 km. Although subduction currently remains only at the edge of the Antarctic Peninsula at the boundary of the Shetland Plate, the cell itself may continue to exist in the upper mantle, including the ascending part beneath the Filchner – Ronne Ice Shelf and in the area of Coats Land.

Rifting and magmatism of East Antarctica could have developed in a different geodynamic setting. The lower mantle plumes under Gondwana in the upper mantle were transformed into subhorizontal mantle flows, which caused the movement of the continents that make up Gondwana in different directions. At present, the remains of the lower mantle plumes that split the southern part of Gondwana are the Kerguelen plume and plateau [19]. During the breakup of Gondwana along the forming rifts, mantle plumes penetrated into the lithosphere of East Antarctica, forming weakened zones in the lithosphere. Subsequently, the restructuring and acceleration of mantle convection led to the reactivation of existing and the formation of new rift zones in the lithosphere of East Antarctica, previously associated with the action of local mantle plumes.

Thus, the activation of rifting in Antarctica in the Late Cenozoic was caused by the general acceleration of global geodynamic processes [28]. The general acceleration of mantle convection was also manifested in active magmatism in Central and East Asia and intense mountain building in the Alpine-Himalayan collision belt [29].

As a result of the activation of global geodynamic processes, the rifts in East Antarctica were reactivated due to upper mantle convection, and subglacial rifting resumed. Due to the high inertia of mantle flows and the large mantle viscosity, rifting processes can still occur today. This is confirmed by the increased heat flow not only in West Antarctica, but also in part of East Antarctica [30, 31]. High heat flow in some parts of East Antarctica indicates tectonic activity at present.

Discussion

Based on new geophysical data (subglacial relief, thickness of sedimentary basins, crustal structure and gravity anomalies) Cenozoic activity in various regions of Antarctica is shown, in particular tectonic activity after glaciation. Possible mechanisms of formation of the deepest continental basins in Antarctica due to long-term stretching processes before and after the breakup of Gondwana with the formation of upper mantle plumes and subsequent general activation of geodynamic processes with volcanism in the Miocene are considered.

It is important to distinguish between depressions of tectonic origin and erosional glacial valleys. The latter are indeed often encountered (mainly in the Australo-Antarctic Block), but they do not extend deep into the continent and do not form isolated intracontinental depressions such as Adventure, Astrolabe, Vostok, etc. The depression of Lake Vostok, according to all geophysical features (steep sides, great depth, sediment layer on the bottom, negative gravity anomalies), is an analogue of the Cenozoic depressions of Baikal and Khövsgöl of the Baikal rift zone, as well as the depressions of Tanganyika, Nyasa, Rudolf, etc. of the East African rift zone. In addition, not all depressions have a meridional extension. For example, the Vanderford and Totten rift depressions have a latitudinal extension, located near the coast, which is not consistent with the general direction of movement of glaciers from the central regions to the periphery.

These results correlate with independent models of subglacial heat flow, such as [30, 31], which indicate increased heat flow in deep subglacial basins, which is an additional sign of rifting. A significant portion of the ice flow into the ocean occurs along meridional rift depressions near the coast of Antarctica. Understanding the processes that occur is important from the point of view of glacier dynamics and balance [32]. Confirmation of artificial heat flow models by real measurements at the ice-rock interface and other instrumental data is needed. Such work is actively underway at Vostok Station in central East Antarctica [33]. For the Lambert Rift, Cenozoic sediments (Miocene-Pliocene), including marine sediments, were found on the sides, at a height of several hundred meters [34, 35]. The uplift of the sides of rift basins is one of the signs of active rifting.

The present day global model of mantle convection based on seismic tomography of the entire mantle does not have a detailed resolution and does not show small convective cells and plumes in the upper mantle. Only the hot subcrustal mantle of the West Antarctic Rift System and the descending mantle flow under the Gamburtsev Mountains are distinguished. The following possible mechanism for the formation and uplift of the Transantarctic Mountains is proposed. Hot material moves subhorizontally in the upper mantle from the Pacific superplume under West Antarctica. Some of it rises, causing volcanism and increased heat flow at the surface. Then the mantle flows reach a vertical barrier in the form of thick and cold lithosphere of East Antarctica at the border with West Antarctica and plunge into the mantle in a descending flow under the Gamburtsev Mountains. However, some of the hot, light material does not sink into the mantle but floats up, causing the edge of East Antarctica to rise and the Transantarctic Mountains to form, which are characterized by the absence of collision origin and abundant volcanism. The process of transporting hot material beneath West Antarctica probably began in the Early Cenozoic as subduction along the coast ceased. This explains the lack of a continuation of the Transantarctic Mountains at the boundary of the Filchner – Ronne Ice Shelf and East Antarctica (see Fig.1, 2). Here, subduction was maintained and the return cell mechanism was realized, and the influx of hot material was impossible. This also explains the negative temperature anomaly under the Filchner – Ronne Ice Shelf compared to the rest of West Antarctica, as well as the absence of active volcanoes in this region [6, 10, 26].

The structure of mantle flows in the South Polar Region can also explain the so-called Alpine relief of the intracontinental Gamburtsev orogen with a thickened crust [3]. The ancient orogen was strongly eroded on the surface by the beginning of the Cenozoic. The cessation of subduction off the coast of West Antarctica led to the formation of a downwelling flow beneath the Gamburtsev Mountains. Before the glaciation of this region in the Eocene, a drop of cold mantle material broke off. This drop began to sink into the mantle under its own weight, and the Gamburtsev Mountains rose to the surface due to isostatic compensation after its separation. Ice then covered them and protected them from further erosion. At present, a drop of cold material is visible in the lower mantle beneath East Antarctica at a depth of 800-1000 km as an area with a negative temperature anomaly (Fig.6). At an average subsidence rate of 2 cm/year, the cold material will reach this depth in about 50 million years. However, the subsidence time may be longer, taking into account the possible retention of material in the transition zone of the mantle at a depth of 660 km.

Conclusion

The cessation of sedimentation after the glaciation of Antarctica and the ongoing rifting led to the formation of deep subglacial depressions. In places where rift basins approach the coast, so-called retrograde slopes are formed: the negative subglacial relief of the basins flattens out sharply towards the coast. This is explained by periodic sedimentation in the coastal area during partial melting of ice during marine transgressions. Rifting involves an increased heat flow, which can lead to the partial melting of the soles of glaciers, contribute to their accelerated slide from the bedrock into the ocean and cause a rapid rise in sea level by tens of centimeters – a few meters. The increased heat flow and partial melting of glaciers explain the confinement of the fastest moving glaciers in Antarctica to the areas of rift basins.

For the first time, mechanisms of formation of the deepest continental rift basins due to the formation of upper mantle plumes under Antarctica after the breakup of the Gondwana supercontinent and the subsequent activation of riftogenic and tectonomagmatic processes in the Miocene are proposed. Numerical geodynamic models of the formation of the Transantarctic Mountains and the uplift of the Gamburtsev intraplate orogen in the Cenozoic are presented. The reduced viscosity at the lower boundary of the upper mantle plays an important role in our numerical models. Detailed regional tomography models beneath the South Polar Region are needed for more accurate numerical modeling.

References

- Leitchenkov G.L., Grikurov G.E. The Tectonic Structure of the Antarctic. Geotectonics. 2023. Vol. 57. Suppl. 1, p. S28-S33. DOI: 10.1134/S0016852123070087

- Morlighem M., Rignot E., Binder T. et al. Deep glacial troughs and stabilizing ridges unveiled beneath the margins of the Antarctic ice sheet. Nature Geoscience. 2020. Vol. 13. Iss. 2, p. 132-137. DOI: 10.1038/s41561-019-0510-8

- Baranov A., Tenzer R., Bagherbandi M. Combined Gravimetric–Seismic Crustal Model for Antarctica. Surveys in Geophysics. 2018. Vol. 39. Iss. 1, p. 23-56. DOI: 10.1007/s10712-017-9423-5

- Jordan T.A., Riley T.R., Siddoway C.S. The geological history and evolution of West Antarctica. Nature Reviews Earth & Environment. 2020. Vol. 1. Iss. 2, p. 117-133. DOI: 10.1038/s43017-019-0013-6

- Lucas E.M., Soto D., Nyblade A.A. et al. P- and S-wave velocity structure of central West Antarctica: Implications for the tectonic evolution of the West Antarctic Rift System. Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 2020. Vol. 546. N 116437. DOI: 10.1016/j.epsl.2020.116437

- van Wyk de Vries M., Bingham R.G., Hein A.S. A new volcanic province: an inventory of subglacial volcanoes in West Antarctica. Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 2018. Vol. 461, p. 231-248. DOI: 10.1144/SP461.7

- Jokat W., Herter U. Jurassic failed rift system below the Filchner-Ronne-Shelf, Antarctica: New evidence from geophysical data. Tectonophysics. 2016. Vol. 688, p. 65-83. DOI: 10.1016/j.tecto.2016.09.018

- Baranov A., Morelli A. The structure of sedimentary basins of Antarctica and a new three-layer sediment model. Tectonophysics. 2023. Vol. 846. N 229662. DOI: 10.1016/j.tecto.2022.229662

- Meijian An, Wiens D.A., Yue Zhao et al. S-velocity model and inferred Moho topography beneath the Antarctic Plate from Rayleigh waves. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth. 2015. Vol. 120. Iss. 1, p. 359-383. DOI: 10.1002/2014JB011332

- Baranov A.A., Lobkovskii L.I., Bobrov A.M. Global Geodynamic Model of the Modern Earth and Its Application to the Antarctic Region. Doklady Earth Sciences. 2023. Vol. 512. Part 1, p. 854-858. DOI: 10.1134/S1028334X23601086

- Leitchenkov G.L., Belyatsky B.V., Kaminsky V.D. The Age of Rift-Related Basalts in East Antarctica. Doklady Earth Sciences. 2018. Vol. 478. Part 1, p. 11-14. DOI: 10.1134/S1028334X18010051

- Migdisova N.A., Sushchevskaya N.M., Portnyagin M.V. et al. Composition of Phenocrysts in Lamproites of Gaussberg Volcano, East Antarctica. Geochemistry International. 2023. Vol. 61. N 9, p. 911-936. DOI: 10.1134/S0016702923090082

- Pappa F., Ebbing J., Ferraccioli F. Moho Depths of Antarctica: Comparison of Seismic, Gravity, and Isostatic Results. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems. 2019. Vol. 20. Iss. 3, p. 1629-1645. DOI: 10.1029/2018GC008111

- Levitan M.A., Leichenkov G.L. Cenozoic glaciation of Antarctica and sedimentation in the Southern Ocean. Lithology and Mineral Resources. 2014. Vol. 49. N 2, p. 117-137. DOI: 10.1134/S0024490214020060

- Scheinert M., Ferraccioli F., Schwabe J. et al. New Antarctic gravity anomaly grid for enhanced geodetic and geophysical studies in Antarctica. Geophysical Research Letters. 2016. Vol. 43. Iss. 2, p. 600-610. DOI: 10.1002/2015GL067439

- Nan Zhang, Zhuo Dang, Chuan Huang, Zheng-Xiang Li. The dominant driving force for supercontinent breakup: Plume push or subduction retreat? Geoscience Frontiers. 2018. Vol. 9. Iss. 4, p. 997-1007. DOI: 10.1016/j.gsf.2018.01.010

- Yoshida M. On mantle drag force for the formation of a next supercontinent as estimated from a numerical simulation model of global mantle convection. Terra Nova. 2019. Vol. 31. Iss. 2, p. 135-149. DOI: 10.1111/ter.12380

- Kotelkin V.D., Lobkovsky L.I. The Myasnikov Global Theory of the Evolution of Planets and the Modern Thermochemical Model of the Earth’s Evolution. Izvestiya, Physics of the Solid Earth. 2007. Vol. 43. N 1, p. 24-41. DOI: 10.1134/S1069351307010041

- Sushchevskaya N.M., Belyatsky B.V., Dubinin E.P., Levchenko O.V. Evolution of the Kerguelen Plume and Its Impact upon the Continental and Oceanic Magmatism of East Antarctica. Geochemistry International. 2017. Vol. 55. N 9, p. 775-791. DOI: 10.1134/S0016702917090099

- Leitchenkov G.L., Dubinin E.P., Grokholsky A.L., Agranov G.D. Formation and Evolution of Microcontinents of the Kerguelen Plateau, Southern Indian Ocean. Geotectonics. 2018. Vol. 52. N 5, p. 499-515. DOI: 10.1134/S0016852118050035

- Golynsky D.A., Golynsky A.V. Unique geological structures of the Law dome and Vanderford and Totten glaciers region (Wilkes Land) distinguished by geophysical data. Arctic and Antarctic Research. 2019. Vol. 65. N 2, p. 212-231 (in Russian). DOI: 10.30758/0555-2648-2019-65-2-212-231

- Koptev A., Cloetingh S., Ehlers T.A. Longevity of small-scale (“baby”) plumes and their role in lithospheric break-up. Geophysical Journal International. 2021. Vol. 227. Iss. 1, p. 439-471. DOI: 10.1093/gji/ggab223

- Jackson M.G., Konter J.G., Becker T.W. Primordial helium entrained by the hottest mantle plumes. Nature. 2017. Vol. 542. Iss. 7641, p. 340-343. DOI: 10.1038/nature21023

- Schmandt B., Jacobsen S.D., Becker T.W. et al. Dehydration melting at the top of the lower mantle. Science. 2014. Vol. 344. N 6189, p. 1265-1268. DOI: 10.1126/science.1253358

- Sobolev A.V., Asafov E.V., Gurenko A.A. et al. Deep hydrous mantle reservoir provides evidence for crustal recycling before 3.3 billion years ago. Nature. 2019. Vol. 571. Iss. 7766, p. 555-559. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-019-1399-5

- Geyer A., Di Roberto A., Smellie J.L. et al. Volcanism in Antarctica: An assessment of the present state of research and future directions. Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 2023. Vol. 444. N 107941. DOI: 10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2023.107941

- Lobkovsky L.I., Ramazanov M.M., Kotelkin V.D. Upper mantle convection related to subduction zone and application of the model to investigate the Cretaceous-Cenozoic geodynamics of Central East Asia and the Arctic. Geodynamics & Tectonophysics. 2021. Vol. 12. N 3, p. 455-470 (in Russian). DOI: 10.5800/GT-2021-12-3-0533

- Yarmolyuk V.V., Nikiforov A.V., Kozlovsky A.M., Kudryashova E.A. Late Mesozoic East Asian Magmatic Province: Structure, Magmatic Signature, Formation Conditions. Geotectonics. 2019. Vol. 53. N 4, p. 500-516. DOI: 10.1134/S0016852119040071

- Trifonov V.G. Collision and mountain building. Geotectonics. 2016. Vol. 50. N 1, p. 1-20. DOI: 10.1134/S0016852116010052

- Lösing M., Ebbing J., Szwillus W. Geothermal Heat Flux in Antarctica: Assessing Models and Observations by Bayesian Inversion. Frontiers in Earth Science. 2020. Vol. 8. N 105. DOI: 10.3389/feart.2020.00105

- Artemieva I.M. Antarctica ice sheet basal melting enhanced by high mantle heat. Earth-Science Reviews. 2022. Vol. 226. N 103954. DOI: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2022.103954

- Reading A.M., Stål T., Halpin J.A. et al. Antarctic geothermal heat flow and its implications for tectonics and ice sheets. Nature Reviews Earth & Environment. 2022. Vol. 3. Iss. 12, p. 814-831. DOI: 10.1038/s43017-022-00348-y

- Bolshunov A.V., Vasilev D.A., Dmitriev A.N. et al. Results of complex experimental studies at Vostok station in Antarctica. Journal of Mining Institute. 2023. Vol. 263, p. 724-741.

- McKelvey B.C., Hambrey M.J., Harwood D.M. et al. The Pagodroma Group – a Cenozoic record of the East Antarctic ice sheet in the northern Prince Charles Mountains. Antarctic Science. 2001. Vol. 13. Iss. 4. P. 455-468. DOI: 10.1017/S095410200100061X

- Tibbett E.J., Scher H.D., Warny S. et al. Late Eocene Record of Hydrology and Temperature From Prydz Bay, East Antarctica. Paleoceanography and Paleoclimatology. 2021. Vol. 36. Iss. 4. N e2020PA004204. DOI: 10.1029/2020PA004204