Digital transformation of industrial machinery repair and maintenance to build an industrial metaverse

- 1 — Ph.D. Associate Professor Empress Catherine II Saint Petersburg Mining University ▪ Orcid

- 2 — Postgraduate Student Empress Catherine II Saint Petersburg Mining University ▪ Orcid

- 3 — Ph.D. Associate professor Empress Catherine II Saint Petersburg Mining University ▪ Orcid

- 4 — Ph.D. Head of Department Shiraz University ▪ Orcid

Abstract

Industrial metaverse is a new direction for development of industrial enterprises. Nowadays the process of full understanding term “industrial metaverse”, its conception, its effectiveness for enterprises is not actualy completed. The methodology, tools, and methods for building an industrial metaverse have not been clearly defined. Therefore, it is advisable to experimentally implement a part of the metaverse on one or several processes with future scaling to other processes. The process of industrial machinery repair and maintenance is proposed as an experimental zone for implementing the industrial metaverse. This process is well suited as an experimental zone. Launching the industrial metaverse concept on it will solve a number of problems, such as the diversity of equipment with unique diagnostic and repair methods, human errors made during repair work, etc. This article presents the concept of building and the architecture of industrial metaverse. A general description of the physical, cyber-physical, and social spaces and the interaction layer between them is provided, without any details of qualitative and quantitative indicators. The avatar of a service engineer is highlighted as one of the elements of the cyber-physical space. The process of creating an avatar of a cyber-physical service engineer is considered: a description of the main functionality is provided, it is shown that a combined system of wearable devices – a glove and a video camera integrated into glasses, a vest, a helmet, or represented by an independent device – is sufficient for its creation. Laboratory experiments were conducted, where the created avatar was tested to determine the task of servicing a centrifugal pump. The results of processing 518 experimental datasets of 10 points, each of which belongs to one of six classes corresponding to a specific technological operation during servicing of a centrifugal pump are shown. Three types of models were obtained (accuracy on training data 0.99; 1.0; 1.0, accuracy on test data 0.625; 0.7; 1.0). It has been shown that achieving 1.0 accuracy on training and test data requires first identifying features representing frequency and temporal characteristics obtained through time series processing. The obtained results allow to make conclusions about the readiness of these technologies for industrial implementation.

Introduction

Modern industrial machinery repair and maintenance is a guarantee of operational safety of any industrial enterprise [1, 2]. Modern maintenance is understood as equipment maintenance performed on time in the required volume, during which the decrease in the enterprise’s operational efficiency is either absent or minimal [3, 4]. During maintenance, enterprises can flow to four strategies [5, 6]: 1) reactive maintenance or maintenance that must be performed upon an incident (repair, accident, etc.); 2) preventive maintenance or scheduled maintenance (according to the manufacturer’s recommendations or regulations); 3) predictive maintenance or maintenance based on defect development forecasts; 4) maintenance based on actual condition (i.e., only when really necessary). Modern enterprises try to move to maintenance based on actual condition and reduce the need for reactive maintenance [7, 8]. During maintenance, enterprises face a number of problems [9, 10], for example:

- lack of labor;

- a huge variety of equipment with unique diagnostic and repair methods;

- a lack of personnel skills and competencies in equipment maintenance;

- a lack of tools for monitoring the actual condition, assessing the service life, and predicting the development of various equipment defects;

- personnel errors occurred during installation or maintenance of equipment, timely logging of these errors and diagnosis;

- a lack of an automated system for monitoring maintenance and personnel actions;

- limited access to real-time information about the life condition of equipment at the facility during repairs.

To solve these and other problems arising during an industrial machinery repair and maintenance, it is necessary to develop new approaches. It made possible by the digital transformation, which is making the transition through Industry 4.0 to Industry 5.0 [11, 12]. Digital transformation today spreads almost all types of human activity [13, 14]. Of course, industry is not immune to it [15, 16]. One of the areas of digital transformation of enterprises and the concept of Industry 5.0 is the creation of an industrial metaverse [17, 18]. The metaverse is a new concept describing a completely immersive digital environment in which people can interact both with digital objects and with each other in virtual space [19]. However, the concept of the “industrial metaverse” is quite new, the principles, methodology and tools of the industrial metaverse have not been clearly defined [20, 21]. There are several problems that hinder its creation in enterprises [22, 23]. For example, the adaptation of existing technological solutions to a specific process and enterprise, the lack of a regulatory framework and standards, insufficient information security, and the absence of a data management system and resource distribution between the real, virtual, and mixed reality. Considering these problems, researchers agree that implementation, i.e., the creation of an industrial metaverse, is necessary today [24, 25].

According to the authors, the implementation of the industrial metaverse should be realized conservatively: a part of the industrial metaverse should be experimentally deployed on one or more processes and then scaled up. However, it is important to remember that even the experimental implementation of a part of the metaverse should not harm the activities of the enterprise or reduce its operational efficiency. The correct selection of an object or process is an important task for the initial deployment of the industrial metaverse. A study [26], the purpose of which was to find out how companies perceive the potential for using the industrial metaverse, showed that maintenance and repair processes have the greatest potential for the implementation of the industrial metaverse: 44 % of votes (first place) versus 15 % for design and planning (second place). This gap proves the advisability of choosing maintenance and repair processes as an experimental zone for the implementation of the industrial metaverse concept. Other studies [27, 28] directly or indirectly choose the equipment maintenance and repair process as the most suitable for the initial implementation of the industrial metaverse concept at an industrial enterprise.

The aim of this work is to develop technical solutions for creating a part of the industrial metauniverse for the equipment maintenance and repair process.

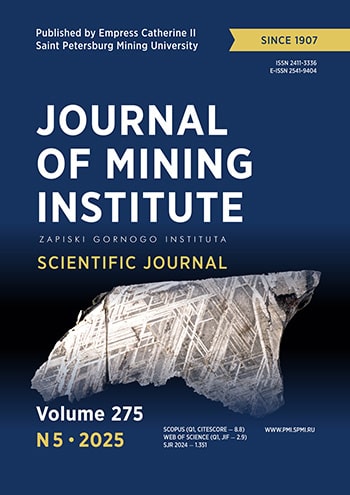

Fig.1. The architecture of the industrial metaverse of industrial machinery repair and maintenance: а – the whole model; b – model in the plane of physical and cyber-physical space

Methods

To build an industrial metaverse of the industrial machinery repair and maintenance process, four mandatory levels or layers are assumed: the physical level (real-world objects), the level of interaction between the physical and virtual worlds (IoT devices, wearable devices, special interaction protocols, communication systems, robots and drones), the mixed reality level (virtual world objects, digital twins, virtual and augmented reality), the decision-making level (objects and algorithms that synchronize the operation of the real and virtual parts of the metaverse). For example, in [29] the industrial metaverse includes physical, cyber-physical, and social spaces. According to this terminology and expanding the industrial metaverse concept, a model of the industrial metaverse was developed, the architecture of which is presented in Fig.1, а.

The difference between this model and the one presented in [29], is that the common layer is called the interaction layer (in [29] the common layer is called the fusion layer, the interaction layer is the layer between the social and cyber-physical space, and additionally introduced are the configuration layer – the layer between the social and physical space, the network layer – the layer between the physical and cyber-physical space, and the perception layer – the layer between the physical and cyber-physical space). The developed architecture allows for a more detailed presentation of the interactions of the three spatial components from different planes. For example, Fig.1, b presents an examination of the industrial metaverse in the plane of interaction between the physical and cyber-physical space.

The real and virtual parts of the industrial metaverse overlap. At the intersection of each part there are data (information models), software services, hardware, and a network layer. At the same time, there is data generated only by the real part of the metaverse, and there is only that which relates to the virtual part, also with software services and hardware. However, the infrastructure should be built in such a way that the parts are independent and can interact with each other.

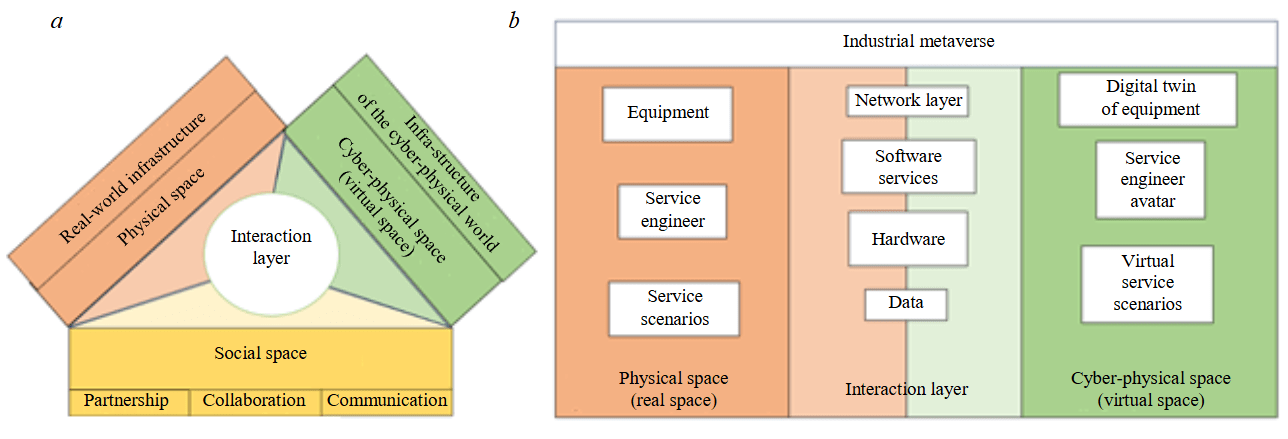

For the presented industrial metaverse architecture, the decision-making system [30] will be located in layers of social space, as shown in Fig.2. The light colors used in Fig.2 for each of the three spaces indicate the boundaries of interaction between the spaces.

Fig.2. Decision-making system in industrial metaverse for industrial machinery repair and maintenance: h – only human, m – only machine, c – collaboration mode

The decision-making system can operate in three modes: human-only, system-only, and interaction mode (expert assistant, where the system generates possible solutions to the problem, and the human makes the final decision). Companies are more willing to delegate decision-making to humans. The system is involved in fewer cases. As trust increases, the degree of system participation in decision-making should certainly increase.

The creation of an industrial metaverse does not occur from scratch. Conceptually, this is certainly a new question, but it is based on existing developments and solutions. For example, for the equipment maintenance and repair process, the physical space exists completely, while the cyber-physical space exists partially. This means that to build an industrial metaverse and understand it in terms of the plane of interaction between the physical and cyber-physical space, it is necessary to improve or supplement the cyber-physical space, as well as the interaction layer. Today, almost all parts of the model in Fig.2 are presented in one form or another as specific technological solutions [31, 32]. The authors see only one element that has not been sufficiently developed in the form of specific software and hardware solutions. This is the avatar of a service engineer or a digital model of a service engineer in cyber-physical space. The experimental part of this study allows to obtaining an avatar of a service engineer. It allows for recording the actions of a service engineer and comparing them with the actual actions performed during repairs. Data suppliers for the development of a service engineer can be special sensors [33, 34] or a machine vision system [35, 36], but the main devices are wearable devices, the range of which on the market is quite wide – helmets [37], glasses [38], vests [39] and even insoles [40].

The hypothesis of experimental part of this research is that to create a digital avatar of a service engineer and implement a system for comparing real maintenance scenes, it is necessary and sufficient to use a combination of devices: a smart glove and a wearable video camera (either a standalone device or integrated into glasses or a hard hat). We emphasize that, despite a certain degree of readiness, even existing solutions require certain upgrades. For example, at the physical level, when interacting with social space, it is necessary to assess personnel's readiness to use various technologies (cognitive-psychological state when using wearable devices, adaptation to interaction with virtual experts, advisory agents, increasing the degree of trust in these technologies), readiness to partner with robots and drones, the availability of regulatory documentation, and ensuring industrial safety of facilities when building a metaverse.

Experiments

Building an industrial metaverse is a resource-intensive process that defies a comprehensive solution. The experiments demonstrate the implementability of only part of the proposed concept. Specifically, they demonstrate the implementation of an avatar of the service engineer in the cyber-physical space of the metaverse. A service engineer in cyber-physical space is defined as an information model with different types of data: the service engineer's position in time and space during repairs; the service engineer's actions and their sequence; and the types and methods of interaction between the service engineer and the equipment.

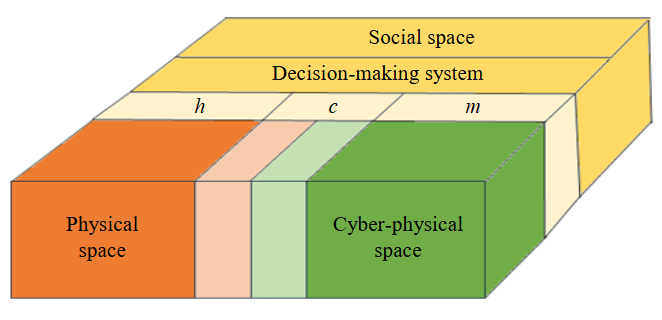

The functionality of the industrial metaverse that can be realized with the implementation of the cyber-physical avatar of the service engineer: generation and creation of maintenance and repair instructions (using digital twins) and their issuance to the service engineer (AR, XR); verification of instruction execution (sequence and correctness of actions); maintenance and repair logging (recording, manual input, voice command, photo recording, video recording, neural interface); assessment of the service engineer competence level; optimization of maintenance and repair process; assessment of the psychophysical and emotional state of the service engineer during maintenance and repair (Fig.3).

Fig.3. A workflow for obtaining a service engineer avatar in the cyber-physical space of the metaverse

Figure 3 shows a workflow for obtaining a service engineer avatar in the cyber-physical space of the metaverse.

To obtain an avatar of a service engineer in the industrial metaverse, three subsystems were developed: a subsystem for determining the position of the service engineer in space, a subsystem for obtaining information about maintenance and repair by processing a video sequence received through a wearable video camera [41], and a subsystem for processing data coming from a smart glove [42].

The subsystem for determining the position of a service engineer in space can be implemented in several ways, at least three. The first method is the simplest, using a locator beacon. The system scans the position of a service engineer relative to the locator beacon. When a service engineer approaches the beacon, the service engineer is within the equipment's service area [43]. The second method is the use of spatial computing (via augmented reality glasses) [44]. The third method is via ZigBee modems [45], for example, using ToF and RSSI methods [46].

Below is the pseudocode for the system's operating algorithm:

Algorithm 1. Get a service engineer avatar in the cyber-physical space of the metaverse.

Output data. Object coordinates (xob, yob, zob), instruction list (a1 … an), mode (collaboration, glove, video).

Step 1. Determine the service engineer's position in space (x, y, z).

Step 2. Check whether the object coordinates match the service engineer's coordinates → Step 1.

Step 3. Accuse hand coordinates and signals from tactile sensors.

Step 4. Check if the mode is collaboration mode → Step 8.

Step 5. Calculate the probability for each class using the video processing system (ρSa1…ρSan) and the glove signal processing system (ρGa1 … ρGan).

Step 6. Determine action ∃an ∈N, max (ρSa1…ρSan, ρGa1 … ρGan).

Step 7. Output data an, t, where an – action from input instruction list, t – current time (timestamp).

Step 8. Check if the mode is glove mode → Step 11.

Step 9. Calculate the probability for each class using the glove signal processing system (ρGa1…ρGan).

Step 10. Determine action ∃an ∈N, max (ρGa1…ρGan) → Step 7.

Step 11. Check if the mode is video mode → Step 4.

Step 12. Calculate the probability for each class using the video processing system (ρSa1 … ρSan).

Step 13. Determine action ∃an ∈N, max (ρSa1 … ρSan) → Step 7.

While solving the same problem, subsystems can be used to label data during model training. For example, a trained video processing subsystem divides the data into specific stages, labeling them, and this information is then used to train a glove signal processing subsystem, and vice versa.

To create a classification model for two processing subsystems, several feature extraction methods were selected and subsequently used for training. Feature extraction significantly improves the quality of time series classification, allowing the model to focus on the most important parts of the data [47]. The wavelet transform method, whose values are characterized by the entropy and energy of the wavelet transform coefficients, was used as a feature extraction method, as well as the calculation of statistical parameters of the time series.

For the video processing subsystem, a dimensionality reduction unit was additionally added. The 42 time series at the input of the dimensionality reduction unit were transformed into 12 time series, 10 of which are the Euler distance between the fingertips and key points of hand N 2, 3, 5, 9, and 17. Two time series are the area of the figure formed by each hand of the service engineer.

Results

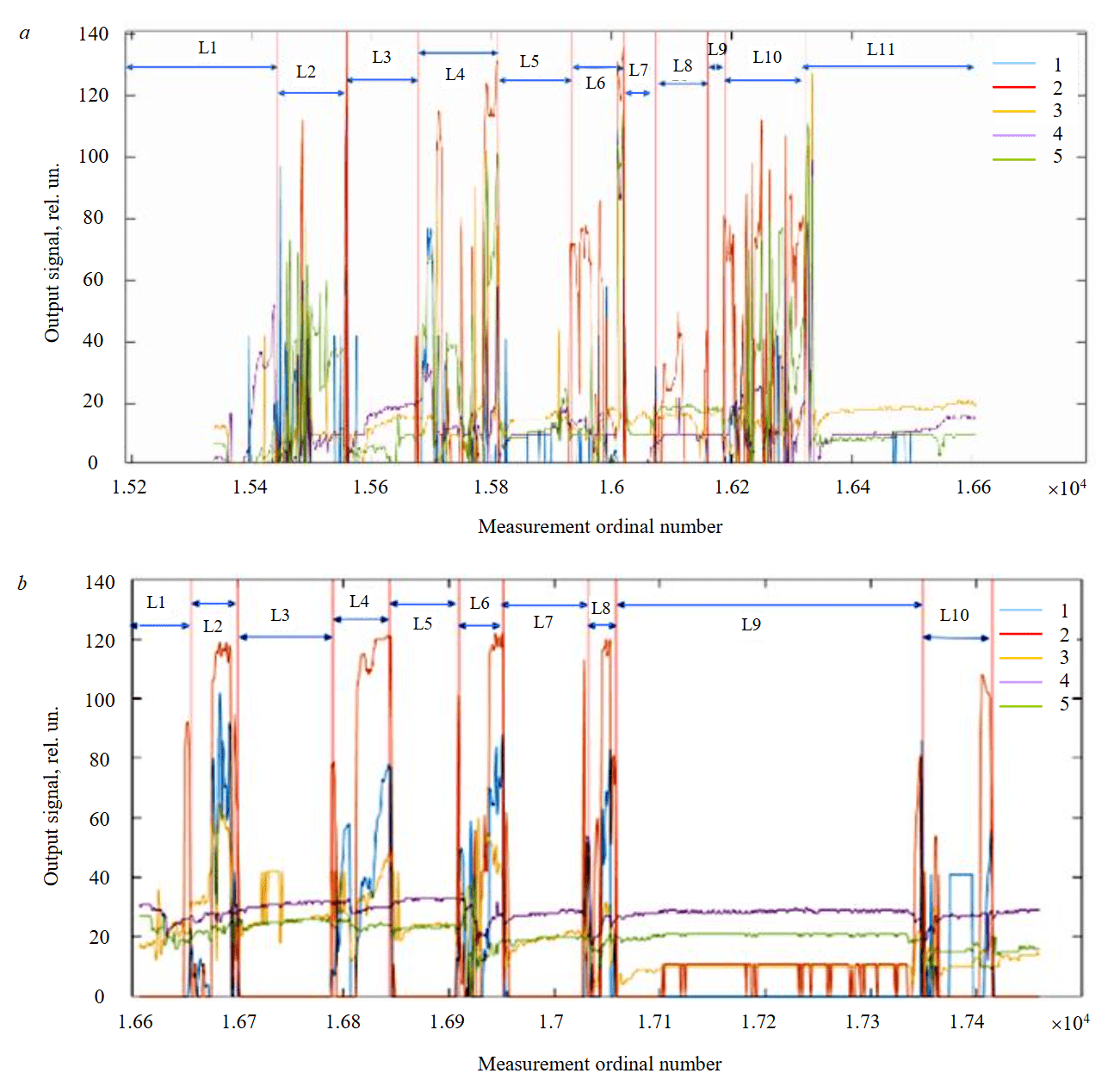

The replacement of the lip seals during maintenance and repair of a centrifugal pump is carried out in the following sequence: removing the protective covers of the coupling; removing the half coupling; removing four nuts from the screws; disconnecting the engine. The following technological operations were used to check the operability of the glove signal processing subsystem: removing and installing the nuts securing the main parts of the pump; loosening and tightening the screws securing the protective cover of the pump electronics unit; recording values in the repair log – recording a short word (parameter value) and recording a long word – recording the features of the repair being performed. The video processing subsystem was not tested, because its description was given earlier [41]. For the experiments, the following classes were determined: class 1 – removing nuts, class 2 – installing nuts, class 3 – loosening a screw, class 4 – tightening a screw, class 5 – recording a short word, class 6 – recording a long word. Figure 4 shows the signal received from five glove sensors.

Fig.4. Sensors data from smart glove, getting during different service operation: a – removing a nut; b – writing a short word

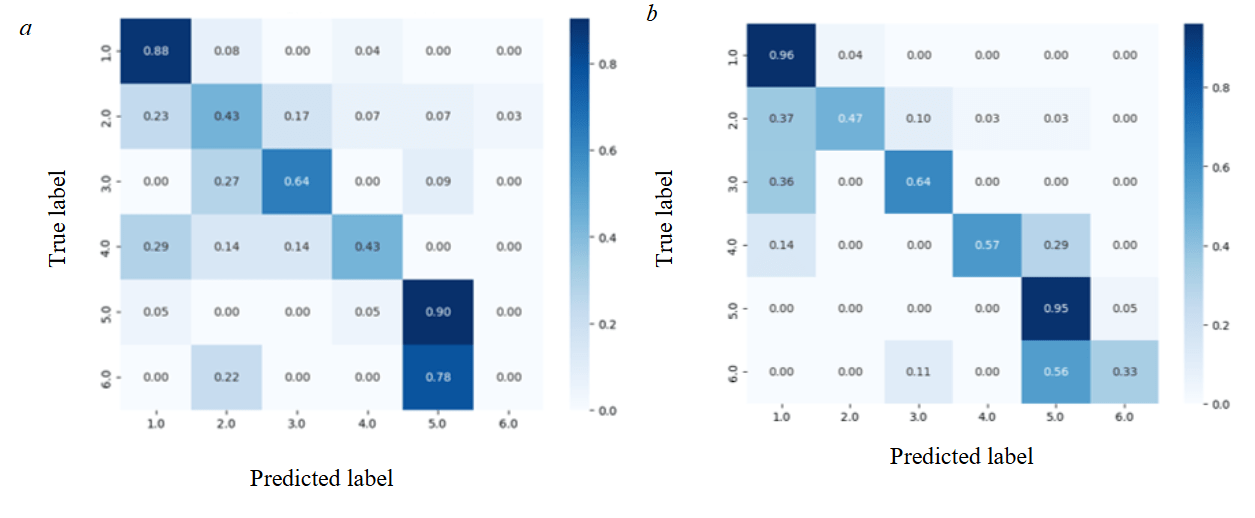

Fig.5. Confusion matrix: а – for method Elastic Ensemble (accuracy train = 0.99, accuracy test = 0.625); b – for method Rocket (accuracy train = 1, accuracy test = 0.7)

As Fig.4, a shows, the data was divided into 11 areas. The initial labeling areas L2, L4, L6, L8, and L10 were revealed as significant. During the servicing, it was additionally recorded that the service engineer removed the nut four times instead of five. Accordingly, one of the regions was identified incorrectly. The video processing system was also launched. Using this system's data, it was determined that region L8 had been labeled incorrectly and that data from regions L2, L4, L6, and L10 should be used for training.

In Fig.4, b, the initial labeling revealed significant regions L2, L4, L6, L8, and L10. The video processing system was also launched. Further verification revealed that all five regions were identified and labeled correctly. Thus, data from five regions was added for training.

Figure 5 shows the results of training the AutoML model using algorithms without preprocessing. The Aeon package and two of its methods suitable for processing multivariable time series data – Rocket [48] and Elastic Ensemble [49] – were used for training. The accuracy values for the Elastic Ensemble training set were 0.99, for Rocket – 1.00, and for the test set – Elastic Ensemble – 0.625, for Rocket – 0.7.

The results obtained during training demonstrate, on the one hand, easy trainability, distinguishability, and satisfactory performance on the task. As can be seen in Fig.5, on the test set, the model most often confused classes are 5 and 6 – “recording a short word” and “recording a long word”. On the other hand, we see signs of overfitting, specifically high performance on the training set and lower performance on the test set. To improve results, it is necessary to perform preprocessing transformations of the time series data and additionally apply feature extraction methods to the algorithms.

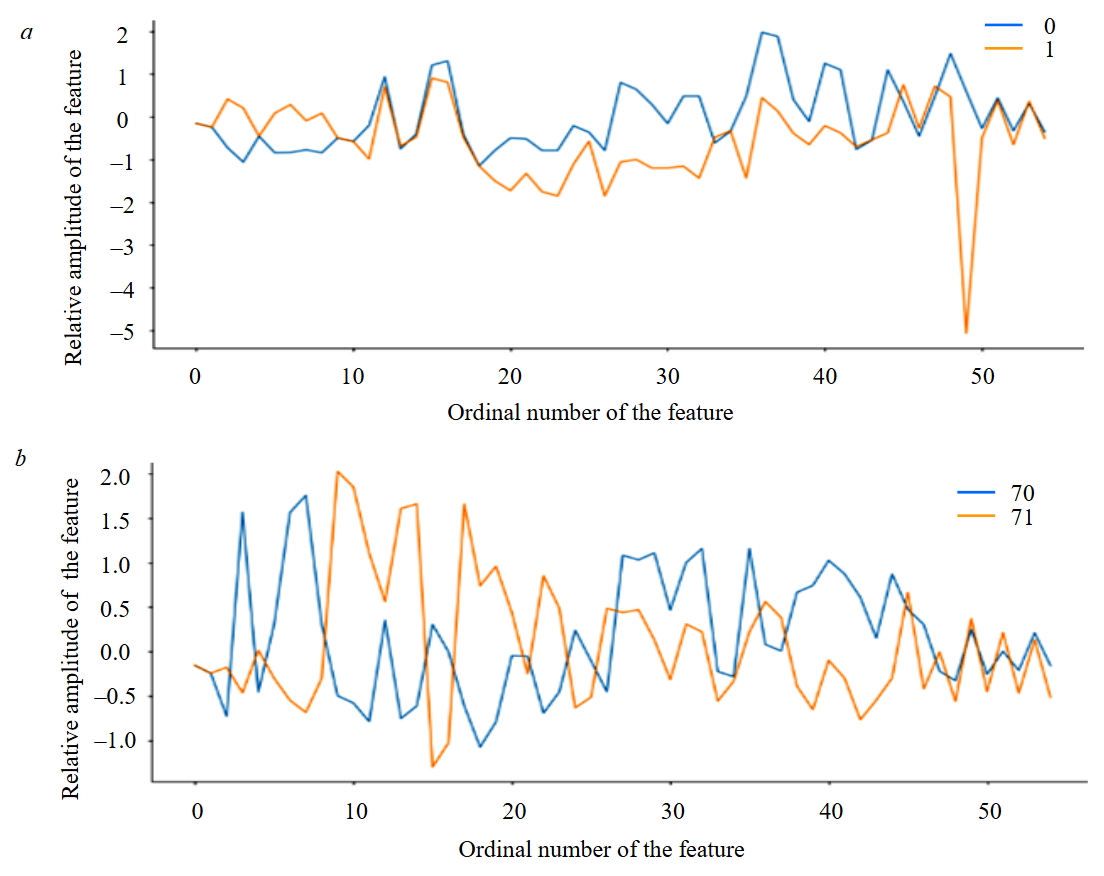

Figure 6 shows a plot of class distinguishability after applying feature extraction methods. Figure 6, a shows class 1 for datasets 0 and 1, and Fig.6, b shows class 2 for datasets 70 and 71. Despite the classes being very similar in the nature of the actions performed, they are visually distinguishable from each other and similar internally.

Fig.6. Class distinguishability graph: a – class 1, data set numbers 0 and 1; b – class 2, data set numbers 70 and 71

The model using feature extraction methods trained perfectly on both the training and test sets, with an accuracy of 1.00.

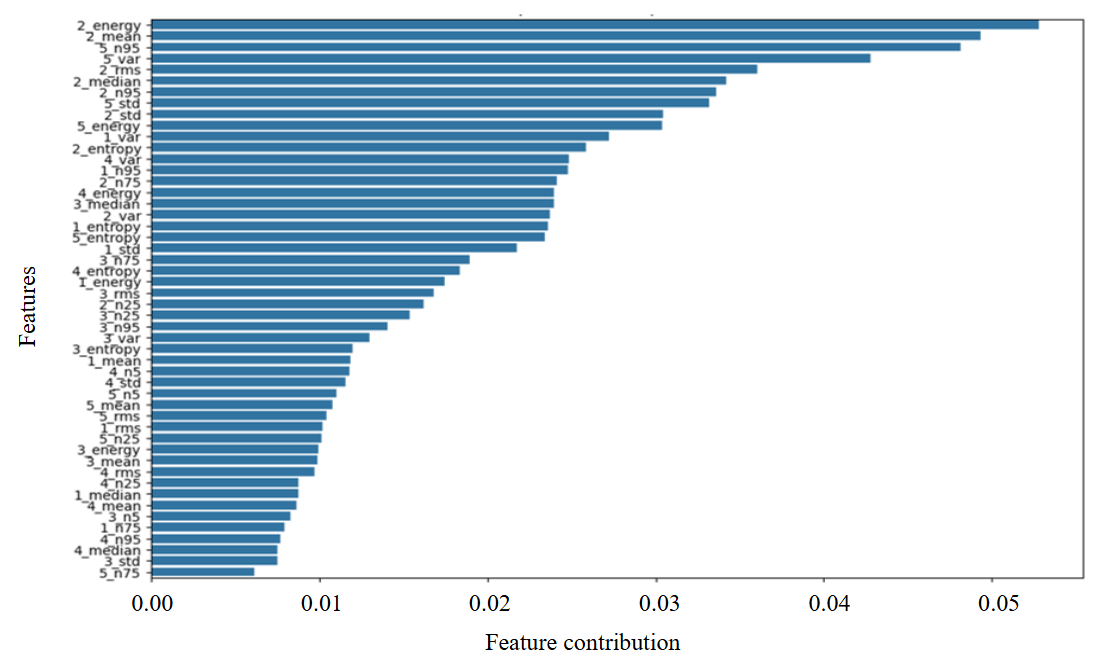

Figure 7 shows the contribution of each feature (the top 20), based on the values of which the model obtained the results. It should be noted that the fingers in the study were coded as follows: 1 – thumb, 2 – index, 3 – middle, 4 – ring, 5 – little finger. It is noteworthy that the index and little fingers made it into the top 10.

Further analysis of such information can help determine the qualifications, work characteristics of the service engineer and other useful information.

Fig.7. Feature contribution

Discussion

Building an industrial metaverse is an important task and provides a foundation for the future development of an industrial enterprise. However, it is important to remember that many solutions have been developed that can be integrated and adapted into the industrial metaverse concept. The collaboration of new and existing solutions and their use within a single conceptual framework should bring profit to the enterprise and open new horizons for production operations.

An example of the new solutions discussed in this article is the creation of a service engineer avatar for use in cyberspace. Integrating the service engineer avatar and its interaction with digital twins of equipment will take an industrial machinery repair and maintenance to a new level.

The experimental part of the study demonstrates the development of only a part of the industrial metaverse for an industrial machinery repair and maintenance. Further work can be focused on various directions, but the most interesting is the following workflow for creating an industrial metaverse: development of a subsystem for monitoring the position of a service engineer in space (especially simplified methods, for example, based on ZigBee network data), development of automatic maintenance and repair scenarios and work plans for the maintenance and repair system, development of a system for evaluating the maintenance and repair system's actions, development of methods for machine-human interaction during maintenance and repair processes, development of methods for optimizing maintenance and repair processes, adaptation of digital twins for use in the industrial metaverse, and verification of the full concept of implementing an industrial metaverse for an industrial machinery repair and maintenance. The extensive plan for further work clearly demonstrates that this work is the initial stage in the construction of an industrial metaverse for the maintenance and repair process.

We emphasize that the smart glove and wearable video camera represent the minimum set of wearable devices that can be used to determine the actions of the service engineer during maintenance and repair. The list of devices and the data obtained from them can be expanded, provided that their data expands the existing functionality. The specified devices and the data obtained from them are sufficient for the presented functions.

When implementing an industrial metaverse, it is necessary to consider potential scaling issues with these solutions. Such issues may include network limitations when using a large number of devices, an exponentially increasing load on the system computing nodes (however, the modularity inherent in the conceptual model will allow for parallelization of computations), and low reliability characteristics of wearable devices, especially when operating in the field.

At all stages of building an industrial metaverse, information security issues must be additionally considered [50]. The interactions of physical space and its operation in unified layers with cyber-physical and social space raise the major issue of information security. The use of new approaches, network protocols, and modern cybersecurity principles (e.g., zero trust security [51, 52], etc.) is key to building an industrial metauniverse. However, it is important to remember that these technologies introduce adjustments to established principles and may require significant changes to the network, software, and hardware implementation of the proposed solutions.

Conclusion

A concept for building an industrial metaverse presents in this article. The applicability of this concept to an industrial machinery repair and maintenance is demonstrated. The analytical section reveals that this process offers the most promising initial approach to building an industrial metaverse. Three types of spaces – physical, cyber-physical, and social – are considered for the industrial metaverse, as well as the interaction layer between them. When considering the industrial metaverse in terms of physical and cyber-physical space, it is necessary to develop missing technological solutions, such as solutions for creating a service engineer's avatar in the cyber-physical space. The experimental section of the study demonstrates that two types of wearable devices – a wearable video camera and a smart glove – are necessary and sufficient for creating an avatar. The process of creating models for comparing data obtained from wearable devices and the work performed by a service engineer is considered. Current developments and future research will reduce costs and maximize profits not only during the operation of the finished “industrial metaverse” product, but also during its development. The company’s transition to Industry 5.0 through Industry 4.0 will enable a new level of production. A key step in implementing new technologies is assessing their readiness and adaptability to existing production realities. Informed decisions, avoiding blind adherence to new trends, ensuring information security, and understanding the global nature of processes during the transition to a new industrial era are essential components of digital transformation.

References

- Bouabid D.A., Hadef H., Innal F. Maintenance as a sustainability tool in high-risk process industries: A review and future directions. Journal of Loss Prevention in the Process Industries. 2024. Vol. 89. N 105318. DOI: 10.1016/j.jlp.2024.105318

- Tokarev I.S., Nazarychev A.N., Shklyarsky Ya.E., Skvortsov I.V. Ensuring the sustainable operation of autonomous power systems in the gas industry. Energetik. 2024. N 7, p. 15-19 (in Russian).

- Mallioris P., Aivazidou E., Bechtsis D. Predictive maintenance in Industry 4.0: A systematic multi-sector mapping. CIRP Journal of Manufacturing Science and Technology. 2024. Vol. 50, p. 80-103. DOI: 10.1016/j.cirpj.2024.02.003

- Nedashkovskaya E.S., Sheshukova E.I., Korogodin A.S. et al. Structure of the system of maintenance and repair of mining machines. Transport, mining and construction engineering: science and production. 2024. N 25, p. 155-162 (in Russian). DOI: 10.26160/2658-3305-2024-25-155-162

- Dayo-Olupona O., Genc B., Celik T., Bada S. Adoptable approaches to predictive maintenance in mining industry: An overview. Resources Policy. 2023. Vol. 86. Part A. N 104291. DOI: 10.1016/j.resourpol.2023.104291

- Wari E., Weihang Zhu, Gino Lim. Maintenance in the downstream petroleum industry: A review on methodology and implementation. Computers & Chemical Engineering. 2023. Vol. 172. N 108177. DOI: 10.1016/j.compchemeng.2023.108177

- Zhukovsky Yu.L., Suslikov P.K. Assessment of the potential effect of applying demand management technology at mining enterprises. Sustainable Development of Mountain Territories. 2024. Vol. 16. N 3 (61), p. 895-908 (in Russian). DOI: 10.21177/1998-4502-2024-16-3-895-908

- Psarommatis F., May G., Azamfirei V. Envisioning maintenance 5.0: Insights from a systematic literature review of Industry 4.0 and a proposed framework. Journal of Manufacturing Systems. 2023. Vol. 68, p. 376-399. DOI: 10.1016/j.jmsy.2023.04.009

- Alves F.F., Ravetti M.G. Hybrid proactive approach for solving maintenance and planning problems in the scenario of Industry 4.0. IFAC-PapersOnLine. 2020. Vol. 53. Iss. 3, p. 216-221. DOI: 10.1016/j.ifacol.2020.11.035

- Palmitessa E., Premoli A., Roda I., Macchi M. Integrating maintenance and energy problems through a Digital Twin-based decision support framework under the guidance of Asset Management. IFAC-PapersOnLine. 2024. Vol. 58. Iss. 8, p. 7-12. DOI: 10.1016/j.ifacol.2024.08.042

- Kans M., Campos J. Digital capabilities driving industry 4.0 and 5.0 transformation: Insights from an interview study in the maintenance domain. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity. 2024. Vol. 10. Iss. 4. N 100384. DOI: 10.1016/j.joitmc.2024.100384

- Ahmed Murtaza A., Saher A., Hamza Zafar M et al. Paradigm shift for predictive maintenance and condition monitoring from Industry 4.0 to Industry 5.0: A systematic review, challenges and case study. Results in Engineering. 2024. Vol. 24. N 102935. DOI: 10.1016/j.rineng.2024.102935

- Litvinenko V.S. Digital Economy as a Factor in the Technological Development of the Mineral Sector. Natural Resources Research. 2020. Vol. 29. Iss. 3, p. 1521-1541. DOI: 10.1007/s11053-020-09716-1

- Korolev N., Kozyaruk A., Morenov V. Efficiency Increase of Energy Systems in Oil and Gas Industry by Evaluation of Electric Drive Lifecycle. Energies. 2021. Vol. 14. Iss. 19, p. 6074. DOI: 10.3390/en14196074

- Cherepovitsyn A., Solovyova V., Dmitrieva D. New challenges for the sustainable development of the rare-earth metals sector in Russia: Transforming industrial policies. Resources Policy. 2023. Vol. 81. N 103347. DOI: 10.1016/j.resourpol.2023.103347

- Makhovikov A.B., Filyasova Yu.A. Information technologies for solid mineral extraction in the Arctic. Sustainable Development of Mountain Territories. 2024. Vol. 16. N 3 (61), p. 1110-1117 (in Russian). DOI: 10.21177/1998-4502-2024-16-3-1110-1117

- Xiao Wang, Yutong Wang, Jing Yang et al. The survey on multi-source data fusion in cyber-physical-social systems: Foundational infrastructure for industrial metaverses and industries 5.0. Information Fusion. 2024. Vol. 107. N 102321. DOI: 10.1016/j.inffus.2024.102321

- Martínez-Gutiérrez A., Díez-González J., Perez H., Araújo M. Towards industry 5.0 through metaverse. Robotics and Computer-Integrated Manufacturing. 2024. Vol. 89. N 102764. DOI: 10.1016/j.rcim.2024.102764

- Alkaeed M., Qayyum A., Qadir J. Privacy preservation in Artificial Intelligence and Extended Reality (AI-XR) metaverses: A survey. Journal of Network and Computer Applications. 2024. Vol. 231. N 103989. DOI: 10.1016/j.jnca.2024.103989

- Hosseini S., Abbasi A., Magalhaes L.G. et al. Immersive Interaction in Digital Factory: Metaverse in Manufacturing. Procedia Computer Science. 2024. Vol. 232, p. 2310-2320. DOI: 10.1016/j.procs.2024.02.050

- Starly B., Koprov P., Bharadwaj A. et al. “Unreal” factories: Next generation of digital twins of machines and factories in the Industrial Metaverse. Manufacturing Letters. 2023. Vol. 37, p. 50-52. DOI: 10.1016/j.mfglet.2023.07.021

- Hosseini S., Abbasi A., Magalhaes L.G. Immersive Interaction in Digital Factory: Metaverse in Manufacturing. Procedia Computer Science. 2024. Vol. 232, p. 2310-2320. DOI: 10.1016/j.procs.2024.02.050

- Shankar A., Gupta R., Kumar A. et al. Exploring the adoption of Enterprise Metaverse in Business-to-Business (B2B) organisations. Industrial Marketing Management. 2025. Vol. 124, p. 224-238. DOI: 10.1016/j.indmarman.2024.11.017

- Kumar A., Shankar A., Behl A. et al. Implementing enterprise metaverse as a means of enhancing growth hacking performance: Will adopting the metaverse be a success in organizations? Journal of Business Research. 2025. Vol. 188. N 115079. DOI: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2024.115079

- Shahzad K., Ashfaq M., Zafar A.U., Basahel S. Is the future of the metaverse bleak or bright? Role of realism, facilitators, and inhibitors in metaverse adoption. Technological Forecasting and Social Change. 2024. Vol. 209. N 123768. DOI: 10.1016/j.techfore.2024.123768

- Salminen K., Aromaa S. Industrial metaverse – company perspectives. Procedia Computer Science. 2024. Vol. 232, p. 2108-2116. DOI: 10.1016/j.procs.2024.02.031

- Shufei Li, Hai-Long Xie, Pai Zheng, Lihui Wang. Industrial Metaverse: A proactive human-robot collaboration perspective. Journal of Manufacturing Systems. 2024. Vol. 76, p. 314-319. DOI: 10.1016/j.jmsy.2024.08.003

- Menezes C., Cunha H., Siqueira G. et al. Metaverse framework for power systems: Proposal and case study. Electric Power Systems Research. 2024. Vol. 237. N 111039. DOI: 10.1016/j.epsr.2024.111039

- Junlang Guo, Jiewu Leng, J. Leon Zhao et al. Industrial metaverse towards Industry 5.0: Connotation, architecture, enablers, and challenges. Journal of Manufacturing Systems. 2024. Vol. 76, p. 25-42. DOI: 10.1016/j.jmsy.2024.07.007

- Oliveri L.M., Lo Iacono N., Chiacchio F. et al. A Decision Support System tailored to the Maintenance Activities of Industry 5.0 Operators. IFAC-PapersOnLine. 2024. Vol. 58. Iss. 8, p. 186-191. DOI: 10.1016/j.ifacol.2024.08.118

- Fede G., Sgarbossa F., Paltrinieri N. Integrating production and maintenance planning in process industries using Digital Twin: A literature review. IFAC-PapersOnLine. 2024. Vol. 58. Iss. 19, p. 151-156. DOI: 10.1016/j.ifacol.2024.09.124

- Sai S., Sharma P., Gaur A., Chamola V. Pivotal role of digital twins in the metaverse: A review. Digital Communications and Networks. 2024. DOI: 10.1016/j.dcan.2024.12.003

- Brahma M., Rejula M.A., Srinivasan B. et al. Learning impact of recent ICT advances based on virtual reality IoT sensors in a metaverse environment. Measurement: Sensors. 2023. Vol. 27. N 100754. DOI: 10.1016/j.measen.2023.100754

- Khokhlov S., Abiev Z., Makkoev V. The Choice of Optical Flame Detectors for Automatic Explosion Containment Systems Based on the Results of Explosion Radiation Analysis of Methane- and Dust-Air Mixtures. Applied Sciences. 2022. Vol. 12. Iss. 3. N 1515. DOI: 10.3390/app12031515

- Romashev A.O., Nikolaeva N.V., Gatiatullin B.L. Adaptive approach formation using machine vision technology to determine the parameters of enrichment products deposition. Journal of Mining Institute. 2022. Vol. 256, p. 677-685. DOI: 10.31897/PMI.2022.77

- Boykov A.V., Payor V.A. Machine vision system for monitoring the process of levitation melting of non-ferrous metals. Tsvetnye Metally. 2023. N 4, p. 85-89 (in Russian). DOI: 10.17580/tsm.2023.04.11

- Lee P., Heepyung Kim, Zitouni M.S. et al. Trends in Smart Helmets With Multimodal Sensing for Health and Safety: Scoping Review. JMIR mHealth and uHealth. 2022. Vol. 10. N 11. N e40797. DOI: 10.2196/40797

- Wagner M., Leubner C., Strunk J. Mixed Reality or Simply Mobile? A Case Study on Enabling Less Skilled Workers to Perform Routine Maintenance Tasks. Procedia Computer Science. 2023. Vol. 217, p. 728-736. DOI: 10.1016/j.procs.2022.12.269

- Rajendran S.D., Wahab S.N., Yeap S.P. Design of a Smart Safety Vest Incorporated With Metal Detector Kits for Enhanced Personal Protection. Safety and Health at Work. 2020. Vol. 11. Iss. 4, p. 537-542. DOI: 10.1016/j.shaw.2020.06.007

- Abdollahi M., Quan Zhou, Wei Yuan. Smart wearable insoles in industrial environments: A systematic review. Applied Ergonomics. 2024. Vol. 118. N 104250. DOI: 10.1016/j.apergo.2024.104250

- Koteleva N., Valnev V. Automatic Detection of Maintenance Scenarios for Equipment and Control Systems in Industry. Applied Science. 2023. Vol. 13. Iss. 24. N 12997. DOI: 10.3390/app132412997

- Koteleva N., Simakov A., Korolev N. Smart Glove for Maintenance of Industrial Equipment. Sensors. 2025. Vol. 25. Iss. 3. N 722. DOI: 10.3390/s25030722

- Surian D., Kim V., Menon R. et al. Tracking a moving user in indoor environments using Bluetooth low energy beacons. Journal of Biomedical Informatics. 2019. Vol. 98. N 103288. DOI: 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103288

- Yuhao Guo, Yicheng Li, Shaohua Wang et al. Pedestrian multi-object tracking combining appearance and spatial characteristics. Expert Systems with Applications. 2025. Vol. 272. N 126772. DOI: 10.1016/j.eswa.2025.126772

- Padma B., Erukala S.B. End-to-end communication protocol in IoT-enabled ZigBee network: Investigation and performance analysis. Internet of Things. 2023. Vol. 22. N 100796. DOI: 10.1016/j.iot.2023.100796

- Pease S.G., Conway P.P., West A.A. Hybrid ToF and RSSI real-time semantic tracking with an adaptive industrial internet of things architecture. Journal of Network and Computer Applications. 2017. Vol. 99, p. 98-109. DOI: 10.1016/j.jnca.2017.10.010

- Mingsen Du, Yanxuan Wei, Yupeng Hu et al. Multivariate time series classification based on fusion features. Expert Systems with Applications. 2024. Vol. 248. N 123452. DOI: 10.1016/j.eswa.2024.123452

- Dempster A., Petitjean F., Webb G.I. ROCKET: exceptionally fast and accurate time series classification using random convolutional kernels. Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery. 2020. Vol. 34. Iss. 5, p. 1454-1495. DOI: 10.1007/s10618-020-00701-z

- Lines J., Bagnall A. Time series classification with ensembles of elastic distance measures. Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery. 2015. Vol. 29. Iss. 3, p. 565-592. DOI: 10.1007/s10618-014-0361-2

- Chaudhuri A., Behera R.K., Bala P.K. Factors impacting cybersecurity transformation: An Industry 5.0 perspective. Computers & Security. 2025. Vol. 150. N 104267. DOI: 10.1016/j.cose.2024.104267

- Azad M.A., Abdullah S., Arshad J. et al. Verify and trust: A multidimensional survey of zero-trust security in the age of IoT. Internet of Things. 2024. Vol. 27. N 101227. DOI: 10.1016/j.iot.2024.101227

- Itodo C., Ozer M. Multivocal literature review on zero-trust security implementation. Computers & Security. 2024. Vol. 141. N 103827. DOI: 10.1016/j.cose.2024.103827