Application of digital simulation methods for predicting parameters of blasted rock muckpile

- Ph.D. Associate Professor Empress Catherine ΙΙ Saint Petersburg Mining University ▪ Orcid

Abstract

The paper considers the features of simulating the blasted rock muckpile formation. We describe various applied approaches and algorithms, as well as discuss the further development of national digital technologies in the mining industry. The study addresses key challenges in simulating explosive impact on rock mass. Due to the significant complexity of mathematical description of rock mass and explosive destruction processes, simulation requires various assumptions that inevitably affect its quality in terms of correspondence to real-world processes. The research compares two approaches to rock fragment dispersion: classical solution based on Newton’s laws and alternative approach assuming that the blasted rock moves as a single indivisible volume at the initial moment of time and fractures only upon contact with the surface. The study demonstrates that, given identical explosive impact and different rock mass representations (2D model with pieces of different sizes and densities), the resulting muckpiles differ significantly. The closest in shape muckpiles for both computation methods are obtained for rock mass simulated with 50 and 100 mm fragments. The obtained results suggest that under certain conditions, it is feasible to use a simplified (alternative) method for simulating the muckpile formation. This approach involves treating the rock movement after explosive impact as a single piece with subsequent fragmentation upon landing.

Introduction

The introduction of various digital solutions in the mining industry is taking place across all areas used in mineral extraction [1, 2], starting with deposit digitalization [3], process simulation [4-6], risk assessment [7, 8], organization of stable and secure communication [9], application of artificial intelligence methods [10, 11], creation of digital twins, introduction of digital assistants, development of automation systems [12, 13], equipment condition diagnostics [14, 15], and ending with the development of full-fledged software packages that store all information about the deposit and stages of its development with full or partial use of Industry 4.0 tools [16, 17].

The computing power of modern computers allows us to return to various mining production tasks that were posed by researchers in the middle of the 20th century, at the dawn of the computer technology era, but could not be solved at that time.

One of these global tasks is predicting the formation of the blasted rock muckpile, which has evolved over time into a more specific task – predicting the location of each point of the blasted block in the muckpile. Thus, the initial task of determining the geometric parameters of the muckpile (width, length, and height) has evolved into a full-scale simulation of rock mass movement during blasting, with determination of any block point’s location at any moment in time. Over the past 50-60 years, there has been a clear trend towards increasing complexity both in problem formulation and in applied solutions. Initially, efforts began with determining 2D or 3D geometry of the muckpile shape and approximate maps of useful component distribution [18], with empirical coefficients (values determined individually for each target) accounting for the influence of blasting parameters and rock mass characteristics. Today, complete simulation of all destruction processes is performed (explosive detonation, stress wave propagation, explosive destruction of the rock mass, and muckpile formation) [19-21], yielding a complete muckpile profile and detailed distribution of the useful component [22] within it. The rock mass was simulated as a matrix of circles (spheres) or squares (cubes) [23, 24], represented as separate blocks (templates), whose dynamics was computed in advance [21, 25, 26]. Various simplifications were introduced to represent the structure of the real rock mass, considering it as an isotropic medium, etc. [27, 28]. The analysis showed that the mechanism of energy transfer from the explosion to the surrounding environment, the specifics of its occurrence [29, 30], and distribution across work types largely determine the formation of the blasted rock muckpile.

Methods

Mathematical modelling of blasted rock muckpile should consider numerous aspects. However, this article focuses on the most essential ones, without which the simulation would be meaningless. These are mathematical descriptions of the research target and the simulated process, which should realistically describe the target’s behaviour in the real world. Otherwise, the simulation results could only be used in the gaming industry or for presentation purposes (visual representations).

For the task under consideration, the research target is a rock mass prepared for blasting (the blasted block or its part); the process is the movement of the blasted rock (movement of each piece). As is known, explosive destruction occurs in several stages [31-33]. In this regard, it is necessary to simulate each stage of the blast. This raises the following issues:

- Different approaches are used when simulating each stage, and the stages overlap in time (they do not occur sequentially).

- Simulation of the research target. Currently, from a simulation perspective, almost nothing is known about the rock mass. For quality simulation, it is necessary to know the rock mass structure (fracturing or initial fragmentation), physical and mechanical properties of each initial rock mass piece (jointing), and its position in space.

- Mathematical description of the rock mass after explosive impact (before movement begins).

While the second problem can still be attempted to be solved using modern technical means (sounding, etc.), the state of the rock mass at the moment of movement is unlikely to be determined experimentally. Many scientists have attempted to perform a complete simulation of the explosion and its impact on the rock mass, but due to the noted complexities, the task has not been solved yet. Therefore, during simulation, researchers resort to major assumptions that, although they allow computations to be performed within an acceptable timeframe, do not always reflect the actual state of things. For example, they represent the rock mass in the form of cubic particles measuring 1×1×1 or 2×2×2 m and simulate the muckpile formation. In real conditions, it is difficult to imagine that the muckpile forms precisely from such particles of blasted rock.

The representation of the rock mass in the form of particles of equal size is considered the most common approach to simulation, used by many researchers (companies like Geomix, Blast Maker, etc.). Simulating the formation of detonation products (impact on the target under study – rock), the propagation of stress waves, and the associated explosive destruction of rocks requires a separate description and is not presented in this article. We use only the final result of these studies. Explosive impact can be simulated differently in various software, therefore it is not specified in the article, just as the blasting parameters used are not mentioned.

The process of rock mass movement is directly related to the mechanism of energy transfer from the explosion to the rock mass. That is, the dispersion of blasted rock occurs due to the pressure exerted on the rock mass by detonation products (gases). With conditionally known explosive impact on the rock mass (pressure of explosion products) and conditionally known state of the rock mass at the initial moment of movement (initial fragmentation), it is possible to simulate the movement of each piece of blasted rock. For this purpose, various libraries are used (physics engines, LS-DYNA, SIMULIA Abaqus, Rocky DEM), actively applied in scientific and gaming computer industries. These tools ensure that target movement strictly follows Newton’s classical mechanics laws [34] and appears quite realistic. With proper tuning of input parameters, good convergence with experimental data can be achieved.

Simulation of blasted block

The main elements used to construct a model of a rock mass prepared for blasting:

- Particle (body) – a rigid target where the distance between any two points remains constant. Bodies can represent ground surface, undisturbed rock mass (static bodies), as well as movable targets (dynamic targets), e.g., fragmented rock pieces.

- Shape – a geometric target that follows the body’s contour, necessary for assigning properties to targets (e.g., elasticity, density) and checking body interactions (collisions).

- Special constraints required for simulating friction between bodies and preventing mutual penetration of bodies, which is permissible in simulation but not in real life.

- Computation module determines body movement over time according to all constraints using discrete time steps.

When resolving one constraint, we violate others, so to obtain an acceptable solution, it is necessary to iterate through all constraints several times (the most resource-intensive task). To simplify the model, the rock mass prepared for blasting is usually simulated from dynamic targets of the same size (square for solving a planar problem, cube for solving a volumetric problem). Each target is placed geometrically so that it describes the contour of the blasted block or its part. The target size can vary, but it is necessary to consider the fact that reducing the size increases the complexity and computation time. Therefore, most often the targets are made with a side equal to 1 or 0.5 m. In this case, we will simulate the target under study in the Rocky software package (the result will be exactly the same in other software packages, since they all use the laws of classical mechanics).

The model under study was constructed as part of a blasted block, limited by the bench and the first row of blastholes. The bench height was 10 m, the slope angle was 70°, the toe burden was 5.6 m, and the first row to the bench edge distance was 2 m. The influence of rock conditions, blasting parameters, and delay intervals are not presented in this article.

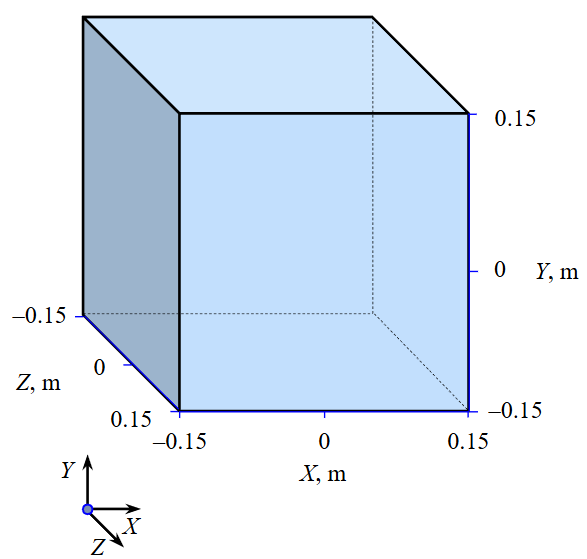

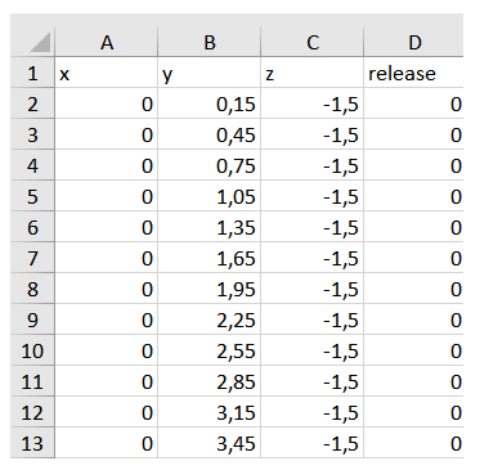

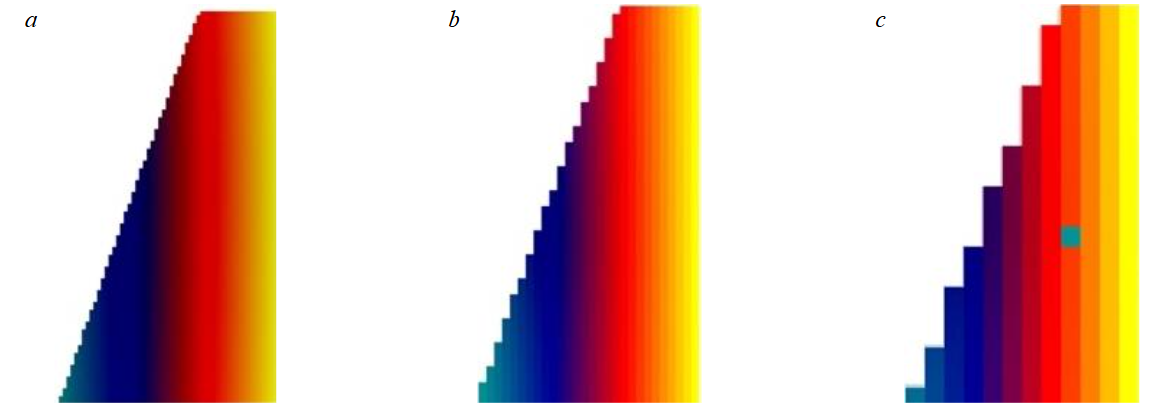

The model was always formed from identical particles of different sizes – ranging from 0.5 to 0.05 m (Fig.1). Since the software used does not provide cubic particles, they were created in an external software (Space Claim graphic editor) and subsequently integrated into the Rocky software. The behaviour of particles with two density values was studied: 1800 and 2500 kg/m3; elastic modulus of 1 GPa; Poisson’s ratio of 0.24; friction coefficient of 0.8; dynamic friction coefficient of 0.7. Particle coordinates were set via CSV files, which specified coordinates and indicated the time of particle appearance in the simulation (Fig.2). The final graphical representation of the models is shown in Fig.3.

Fig.1. Simulated particle with a size of 0.3 m

Fig.2. Fragment of CSV file with particle coordinate information

Fig.3. Models formed from particles of different sizes: a – 0.1 m; b – 0.2 m; c – 0.3 m

In this case, the colour scheme does not carry any semantic meaning and serves purely for presentation purposes. However, all similar software provides the ability to track the movement of individual parts of the rock mass. Despite the fact that the particles were set as solid bodies, in this particular case, a planar problem was solved. To prevent particle movement in the third dimension, two transparent walls with a zero friction coefficient were artificially added to the model, between which the particles moved. The already blast-destroyed rock mass is being simulated, so the fact that blastholes are overdrilled and rock masses below the bench toe are exposed to blast impact is ignored.

Simulation of dispersion

After developing the rock mass model, it is necessary to simulate the explosive impact. For this purpose, the applied physics engine (similar in others) provides the following capabilities: setting force, torque, and impulse. Full-scale simulation of blasted rock fragment dispersion and muckpile formation is quite a challenging task. This study compares two methods of muckpile simulation: classical and with assumptions (alternative):

- Particle dispersion along ballistic trajectories with determination of particle coordinates at any moment in time (classical problem).

- Initial movement of rock mass as a single piece with subsequent dispersion at the moment of landing (simplified problem).

Our study tests the hypothesis about the formation of the muckpile as the movement of the entire volume of blasted rock to a certain distance, followed by dispersion of rock mass fragments upon impact with the surface. This assumption was based on the analysis of high-speed camera video recordings of explosions made during research work at one of the deposits in Yakutia.

Experiments

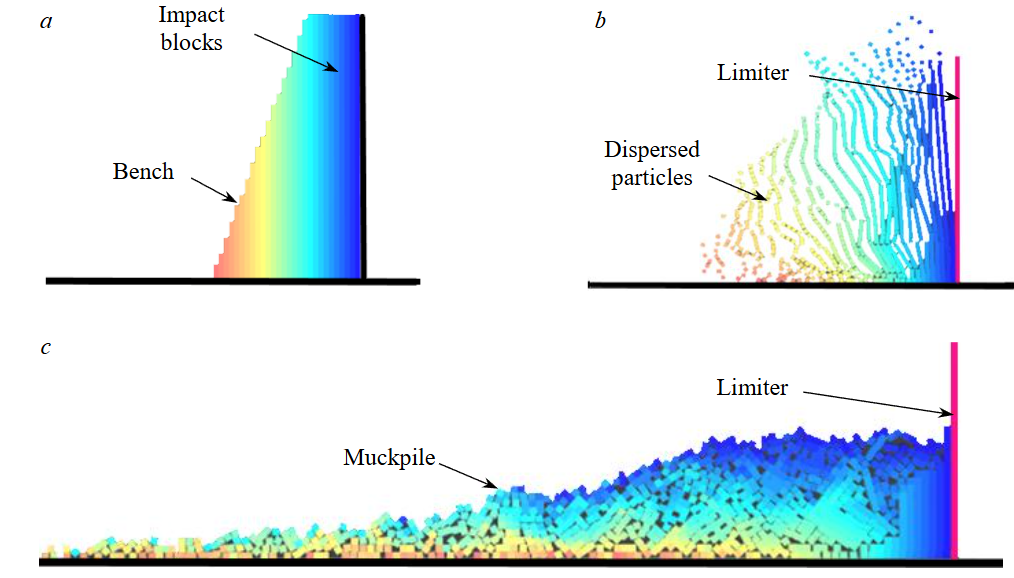

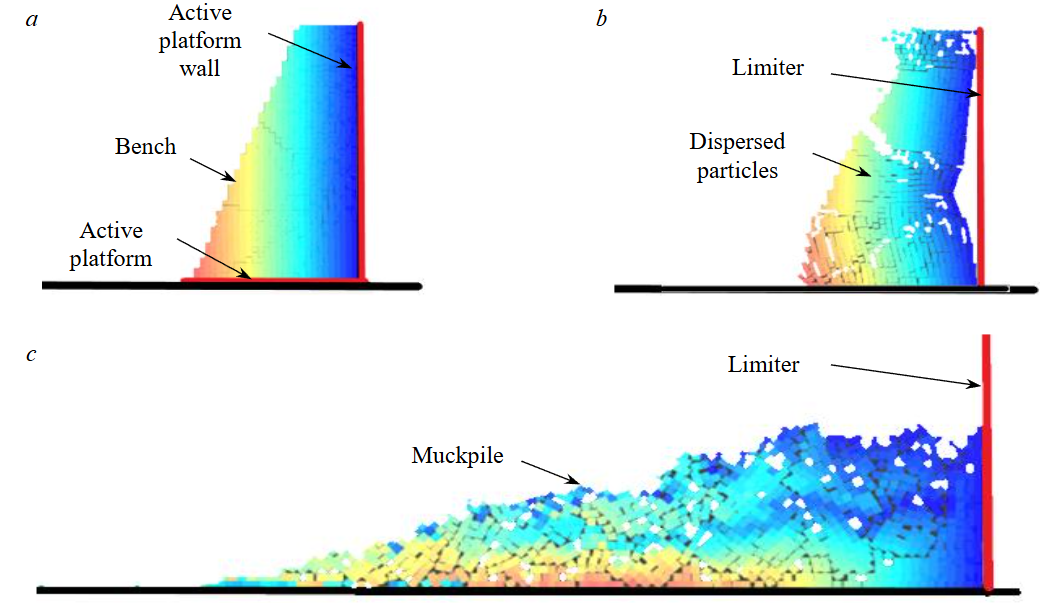

Particle dispersion along ballistic trajectories with determination of particle coordinates at any moment in time. In the classical case, the explosive impact on particles (setting rocks in motion) was specified through the Motion Frames function. After the start of movement, a special limiter was created to prevent particles from dispersion to the right, towards the undisturbed rock mass. The initial state of the model (before the start of movement) (Fig.4, a), the moment of particle dispersion (Fig.4, b), and the final state (muckpile) (Fig.4, c) are presented.

Initial movement of rock mass as a single piece with subsequent dispersion at the moment of landing. This alternative task considers the movement of the block as a single piece. In this case, after explosive impact, the block moves as a single piece and destroys into parts only at the moment of its contact with the surface. The movement of rocks is specified using a platform that moves the centre of gravity of the block at an angle of 45° with a speed of 2 m/s along the vertical and horizontal axes (Fig.5, a). After 0.05 s, the impact ceased, the block continued to move under the influence of inertial forces and dispersed upon contact with the surface. As in the first case, a special limiter was created to prevent particles from dispersion to the right, towards the undisturbed rock mass (Fig.5, b). Figure 5, c presents the final state of the rocks.

Fig.4. Simulation stages according to the classical variant [35]

Fig.5. Simulation stages according to the alternative variant [35]

Research results

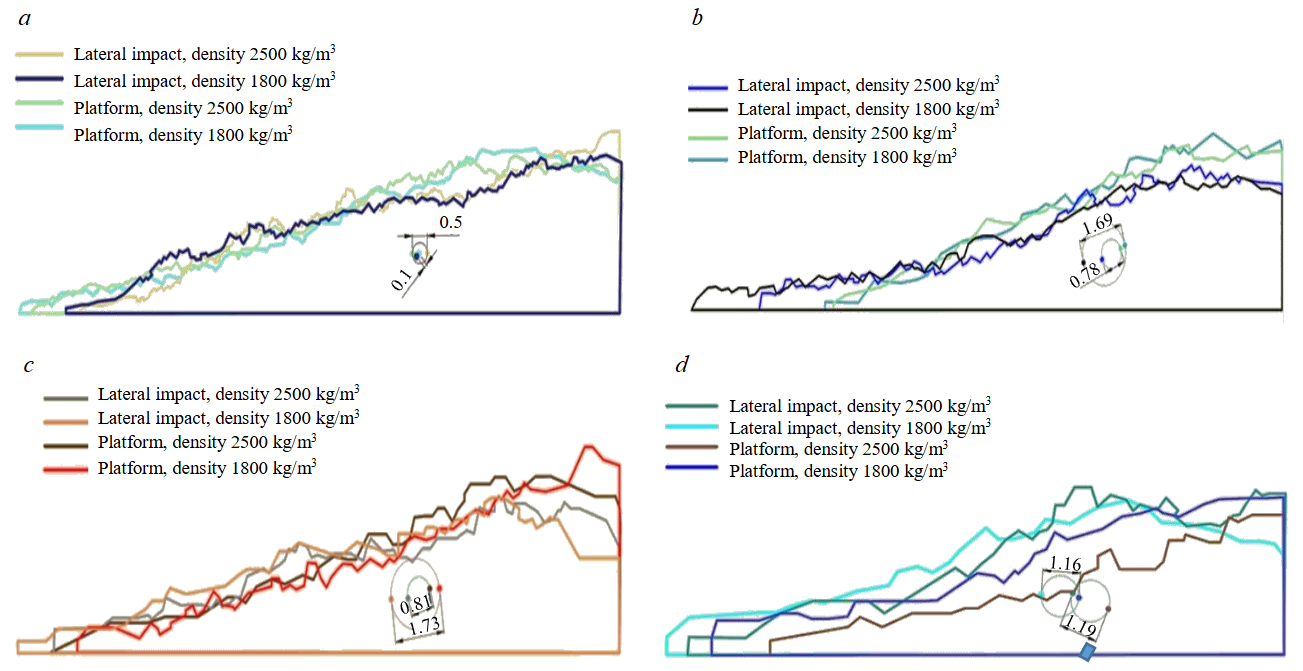

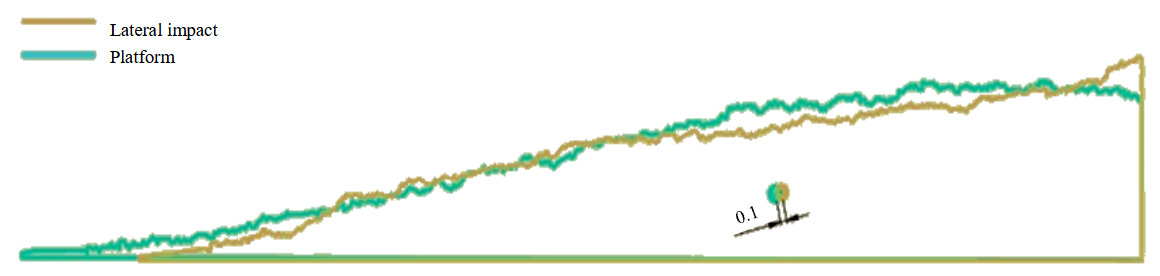

When comparing muckpiles obtained using different methods, the following parameters were selected as criteria: muckpile width, height, and angle; distance to the muckpile centre of mass; difference between centres of mass, and time required for simulation. The centre of gravity coordinates of the muckpiles were determined using the Space Claim software, while the contour of the obtained muckpiles was traced in AutoCAD. The parameters of the muckpiles obtained in this way are presented in Fig.6. The numbers in the figures show the difference in metres between the centres of mass of the muckpiles obtained using different methods. For example, the difference in centres of mass of the muckpiles for particles measuring 100 mm with a density of 2500 kg/m3 is 0.5 m (Fig.6, a). For particles measuring 0.05 m, the muckpiles were simulated only under the condition that their density was 1800 kg/m3 (Fig.7). The results of discrepancies in the parameters of the muckpile obtained using different methods for particles of the same size and density are presented in the Table.

Fig.6. Comparison of muckpile contours and centres of mass [35] for particles of different sizes: a – 0.1 m; b – 0.2 m; c – 0.3 m; d – 0.5 m

Fig.7. Comparison of muckpile contours and centres of mass distribution [35]

Simulation results

|

Particle size, m |

Density, kg/m3 |

Difference between centres of mass, m |

Difference in muckpile height, m |

Difference in muckpile width, m |

Difference in muckpile height, % |

Difference in muckpile width, % |

|

0.5 |

1800 |

1.16 |

0.06 |

1.39 |

1.36 |

7.29 |

|

0.5 |

2500 |

1.19 |

0.79 |

2.57 |

16.53 |

13.92 |

|

0.3 |

1800 |

1.73 |

0.37 |

2.10 |

9.76 |

9.86 |

|

0.3 |

2500 |

0.81 |

0.52 |

0.15 |

13.72 |

0.75 |

|

0.2 |

1800 |

1.69 |

0.81 |

5.49 |

22.50 |

23.71 |

|

0.2 |

2500 |

0.78 |

0.84 |

2.58 |

21.71 |

12.54 |

|

0.1 |

1800 |

0.10 |

0.02 |

1.14 |

0.53 |

6.08 |

|

0.1 |

2500 |

0.50 |

0.05 |

1.85 |

1.28 |

10.05 |

|

0.05 |

1800 |

0.10 |

0.01 |

1.15 |

0.32 |

5.24 |

Discussion

The results of simulation strongly depend on the specified boundary conditions. For example, under identical conditions, the muckpile height for particles measuring 0.5×0.5 m is 4.41-4.47 m, while for particles measuring 0.1×0.1 m it is 3.9-3.95 m. The results of simulating muckpile formation using various approaches showed that as the piece size and density decrease, the difference between the centres of mass of the muckpiles formed according to the first and second problems decreases. The smallest deviation of 0.1 m is observed for particle density of 1800 kg/m3 and particle sizes of 0.05 and 0.1 m. The remaining parameters for these particles differ by no more than 5 %.

This allowed us to conclude that under certain conditions, muckpile formation can be carried out using a simplified method – considering the movement of the rock mass as a single piece with subsequent dispersion at the moment of landing. This approach was implemented in the developed software [36]. In the first approximation, the problem was solved in a planar formulation, which is a very significant assumption [37]. Modern computing capabilities make it possible to perform this research in a 3D formulation. Currently, these works are being actively conducted at the Educational Centre of Digital Technologies of the Mining University.

Due to the market-out of foreign companies from Russia, there is a shift towards software packages developed by Russian experts. The simplest and fastest way is to copy all existing solutions. In this process, both solutions and terms used in the original product are copied into software packages. It should be noted that Russian legislation prohibits the use of foreign words when Russian equivalents exist.

A simple replacement of foreign software with a similar Russian development (which copies the foreign product) will not increase enterprise efficiency. It is necessary to create new software products with solutions that surpass existing foreign developments. A technological and scientific breakthrough will occur through the joint efforts of all developers (at least in terms of standardization and data exchange). Without this, it is impossible to create an advanced software package with functionality that meets the needs of the entire mining industry. To use complex software packages effectively, it is necessary to have a deep understanding of all the intricacies of mining production processes, which is impossible without receiving quality specialized education [38].

While digital technologies are transforming our world, they remain merely tools for accomplishing our goals. Recently, mining science was considered an art form [39], with many uncertainties that are difficult to describe in mathematical terms. Often, in the author’s opinion, it is necessary to simply listen to one’s intuition and to people who work directly in production and know all the intricacies of the work. It seems that the final adjustment of the used software package together with such people is the right management decision for leaders.

Conclusion

From a scientific point of view, the most correct solution for simulating the muckpile (the final stage of explosive destruction) is to estimate the movement of each individual piece of blasted rock based on classical Newtonian mechanics. However, this requires significant computational resources, and the rock pieces must be of different sizes and shapes. The use of alternative approaches, such as those presented in this article, requires firstly scientific justification, secondly, a description of the boundaries of use (it may not be suitable for all conditions), as well as mandatory industrial validation.

The formation of the blasted rock muckpile is a complex and still unsolved problem. Currently, there are only certain simplifications of the classical problem solution. If the boundary conditions are incorrectly specified, researchers will obtain results that differ from reality. Simplification of the problem should be based on knowledge [38] about explosive destruction processes; otherwise, researchers will go down the wrong path. When implementing any solution using software tools, all simplifications and assumptions used must be communicated to potential users.

References

- Makhovikov A.B., Filyasova Yu.A. Information technologies for solid mineral extraction in the Arctic. Sustainable Devel-opment of Mountain Territories. 2024. Vol. 16. N 3, p. 1110-1117 (in Russian). DOI: 10.21177/1998-4502-2024-16-3-1110-1117

- Fomin S.I., Govorov A.S. Strategy of formation of operating space in open pit mines based on cut-off grade control. Mining Informational and Analytical Bulletin. 2024. N 11, p. 165-179 (in Russian). DOI: 10.25018/0236_1493_2024_11_0_165

- Egorov A.S., Kalinin D.F., Sekerina D.D. Geotectonic model of the deep structure of the Zmeinogorsky ore district of Rudny Altai according to geological interpretation of geophysical survey complex. Bulletin of the Tomsk Polytechnic University. Geo Assets Engineering. 2024. Vol. 335. N 8, p. 148-160 (in Russian). DOI: 10.18799/24131830/2024/8/4431

- Bagautdinov I.I., Belyakov N.A., Sevryukov V.V., Rasskazov M.I. Hardening soil model in prediction of plastic deformation zone in soft rock mass of Yakovlevo iron ore deposit. Gornyi zhurnal. 2022. N 12, p. 16-21 (in Russian). DOI: 10.17580/gzh.2022.12.03

- Zhukovskiy Yu.L., Suslikov P.K. Assessment of the potential effect of applying demand management technology at mining enterprises. Sustainable Development of Mountain Territories. 2024. Vol. 16. N 3, p. 895-908 (in Russian). DOI: 10.21177/1998-4502-2024-16-3-895-908

- Galimyanov A.A., Kazarina E.N. Clarification of the formula for the relevance of well collection. Bulletin of the Kuzbass State Technical University. 2025. N 2 (168), p. 94-100 (in Russian). DOI: 10.26730/1999-4125-2025-2-94-100

- Shojaee Barjoee S., Rodionov V. Mathematical modeling and optimization of workplace illumination in ceramic industries (Iran) using DIALux evo. Journal of Infrastructure, Policy and Development. 2024. Vol. 8. N 15. N 5918. DOI: 10.24294/jipd5918

- Shojaee Barjoee S., Rodionov V.A. Respirable Dust in Ceramic Industries (Iran) and its Health Risk Assessment using De-terministic and Probabilistic Approaches. Pollution. 2024. Vol. 10. Iss. 4, p. 1206-1226. DOI: 10.22059/POLL.2024.376043.2360

- Makhovikov A.B., Kryltsov S.B., Matrokhina K.V., Trofimets V.Ya. Secured communication system for a metallurgical company. Tsvetnye metally. 2023. N 4, p. 5-13 (in Russian). DOI: 10.17580/tsm.2023.04.01

- Sekerina D.D., Saitgaleev M.M., Senchina N.P. et al. Role of strike-slips and graben-rifts in controlling oil and gas reser-voirs in deep horizons of the Russko-Chaselsky Ridge (West Siberian Province). Mining Science and Technology. 2025. Vol. 10. N 2, p. 109-117. DOI: 10.17073/2500-0632-2025-02-399

- Zaytseva E.V., Kochneva A.A., Katuntsov E.V., Kiba M.R. Approaches to digital image processing in the mining industry. XXI Century: Resumes of the Past and Challenges of the Present plus. 2024. Vol. 13. N 1 (65), p. 62-67 (in Russian).

- Romashev A.O., Nikolaeva N.V., Gatiatullin B.L. Adaptive approach formation using machine vision technology to determine the parameters of enrichment products deposition. Journal of Mining Institute. 2022. Vol. 256, p. 677-685. DOI: 10.31897/PMI.2022.77

- Rasskazov I.Yu., Fedotova Yu.V., Anikin P.A. et al. Improvement of the automated system of geomechanical monitoring and early prevention of dangerous geodynamic phenomena. Mining Informational and Analytical Bulletin. 2022. N 12-1, p. 106-121 (in Russian). DOI: 10.25018/0236_1493_2022_121_0_106

- Koteleva N., Korolev N. A Diagnostic Curve for Online Fault Detection in AC Drives. Energies. 2024. Vol. 17. Iss. 5. N 1234. DOI: 10.3390/en17051234

- Koteleva N., Valnev V. Automatic Detection of Maintenance Scenarios for Equipment and Control Systems in Industry. Applied Sciences. 2023. Vol. 13. Iss. 24. N 12997. DOI: 10.3390/app132412997

- Klebanov A.F., Bondarenko A.V., Zhukovsky Yu.L., Klebanov D.A. Establishing remote control centers of a mining operation: strategic prerequisites and implementation stages. Russian Mining Industry. 2024. N 4, p. 174-183 (in Russian). DOI: 10.30686/1609-9192-2024-4-174-183

- Lukichev S.V., Nagovitsyn O.V. Digital transformation and technological independence of the mining industry. Russian Mining Industry. 2022. N 5, p. 74-78 (in Russian). DOI: 10.30686/1609-9192-2022-5-74-78

- Yang R.L., Kavetsky A. A three dimensional model of muckpile formation and grade boundary movement in open pit blasting. International Journal of Mining and Geological Engineering. 1990. Vol. 8. Iss. 1, p. 13-34. DOI: 10.1007/BF00881125

- Zhi Yu, Xiu-Zhi Shi, Zong-Xian Zhang et al. Numerical Investigation of Blast-Induced Rock Movement Characteristics in Open-Pit Bench Blasting Using Bonded-Particle Method. Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering. 2022. Vol. 55. Iss. 6, p. 3599-3619. DOI: 10.1007/s00603-022-02831-w

- Wei Fu, Furtney J., Valencia J. Blast Movement Simulation Through a Hybrid Approach of Continuum, Discontinuum, and Machine Learning Modeling. 57th U.S. Rock Mechanics/Geomechanics Symposium, 25-28 June 2023, Atlanta, GA, USA. OnePetro, 2023. N ARMA-2023-0831. DOI: 10.56952/ARMA-2023-0831

- Zhixian Hong, Ming Tao, Mingsheng Zhao et al. Numerical modelling of rock fragmentation under high in-situ stresses and short-delay blast loading. Engineering Fracture Mechanics. 2023. Vol. 293. N 109727. DOI: 10.1016/j.engfracmech.2023.109727

- Yanitskii E.B., Kabelko S.G., Dunaev V.A., Rakhmanov R.A. Computer simulation of displacement of rock mass and estimation of ore dilution as a result of massive explosion in the open mining. Explosion technology. 2018. N 120/77, p. 94-108 (in Russian).

- Kucewicz M., Łukasz M., Baranowski P. et al. Numerical modeling of blast-induced rock fragmentation in deep mining with 3D and 2D FEM method approaches. Journal of Rock Mechanics and Geotechnical Engineering. 2024. Vol. 16. Iss. 11, p. 4532-4553. DOI: 10.1016/j.jrmge.2024.01.017

- Sellers E., Furtney J., Onederra I., Chitombo G. Improved understanding of explosive–rock interactions using the hybrid stress blasting model. The Journal of The Southern African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy. 2012. Vol. 112. Iss. 8, p. 721-728.

- Vasylchuk Y.V., Deutsch C.V. Approximate blast movement modelling for improved grade control. Mining Technology. 2019. Vol. 128. Iss. 3, p. 152-161. DOI: 10.1080/25726668.2019.1583843

- Cundall P.A., Strack O.D.L. A discrete numerical model for granular assemblies. Géotechnique. 1979. Vol. 29. Iss. 1, p. 47-65. DOI: 10.1680/geot.1979.29.1.47

- Hosseini S., Poormirzaee R., Hajihassani M. An uncertainty hybrid model for risk assessment and prediction of blast-induced rock mass fragmentation. International Journal of Rock Mechanics and Mining Sciences. 2022. Vol. 160. N 105250. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijrmms.2022.105250

- Zharikov I.F., Zakharov V.N., Norel B.K. Strength passport and relation equation between stress and strain invariants for inhomogeneous rocks under volumetric stress state. Izvestiya Rossiiskoi akademii nauk. Mekhanika tverdogo tela. 2015. N 6, p. 49-60 (in Russian).

- Moldovan D.V., Chernobay V.I., Yastrebova K.N. The influence of composite material in the stemming design on its operability. Mining Informational and Analytical Bulletin. 2023. N 9-1, p. 110-121 (in Russian). DOI: 10.25018/0236_1493_2023_91_0_110

- Moldovan D.V., Chernobay V.I., Sokolov S.T., Bazhenova A.V. Design concepts for explosion products locking in chamber. Mining Informational and Analytical Bulletin. 2022. N 6-2, p. 5-17 (in Russian). DOI: 10.25018/0236_1493_2022_62_0_5

- Kazakov N.N., Viktorov S.D., Shlyapin A.V., Lapikov I.N. Rock crushing by blasting in open-pit mines. Мoscow: Rossiiskaya akademiya nauk, 2020, p. 520 (in Russian).

- Kurinnoi V.P. Theoretical foundations of explosive rock destruction. Dnepr, 2018, p. 280 (in Russian).

- Peng Xu, Renshu Yang, Jinjing Zuo et al. Research progress of the fundamental theory and technology of rock blasting. International Journal of Minerals, Metallurgy and Materials. 2022. Vol. 29. Iss. 4, p. 705-716. DOI: 10.1007/s12613-022-2464-x

- Verbilo P., Karasev M., Belyakov N., Iovlev G. Experimental and numerical research of jointed rock mass anisotropy in a three-dimensional stress field. Rudarsko-geološko-naftni zbornik. 2022. Vol. 37. N 2, p. 109-122. DOI: 10.17794/rgn.2022.2.10

- Bazhenova A.V. Forecasting ore contour displacement during blasted rock muckpile formation in open-pit mines: Avtoref. kand. dis. … tekhn. nauk. Saint Petersburg: Sankt-Peterburgskii gornyi universitet, 2023, p. 20 (in Russian).

- Koteleva N.I., Khokhlov S.V., Bazhenova A.V. Certificate of state registration of computer program N 2024660948 of the Russian Federation. Program for determining ore contour displacement during blasted rock muckpile formation. Publ. 14.05.2024. Bul. N 5 (in Russian).

- Engmann E., Ako S., Bisiaux B. et al. Measurement and Modelling of Blast Movement to Reduce Ore Losses and Dilution at Ahafo Gold Mine in Ghana. Ghana Mining Journal. 2013. Vol. 14, p. 27-36.

- Litvinenko V.S. Digital Economy as a Factor in the Technological Development of the Mineral Sector. Natural Resources Research. 2020. Vol. 29. Iss. 3, p. 1521-1541. DOI: 10.1007/s11053-019-09568-4

- Rudnik S.N., Afanasev V.G., Samylovskaya E.A. 250 years in the service of the Fatherland: Empress Catherine II Saint Petersburg Mining University in facts and figures. Journal of Mining Institute. 2023. Vol. 263, p. 810-830.