Minerals of the crichtonite group in ooids of mineralized volcaniclastic rocks from the Rudnogorskoe iron deposit (Eastern Siberia)

- 1 — Ph.D. Leading Researcher South Ural Scientific Centre Mineralogy and Environmental Geology of the Ural Branch RАS ▪ Orcid

- 2 — Ph.D., Dr.Sci. Chief Researcher South Ural Scientific Centre Mineralogy and Environmental Geology of the Ural Branch RАS ▪ Orcid

- 3 — Junior Researcher South Ural Scientific Centre Mineralogy and Environmental Geology of the Ural Branch RАS ▪ Orcid

- 4 — Junior Researcher South Ural Scientific Centre Mineralogy and Environmental Geology of the Ural Branch RАS ▪ Orcid

- 5 — Ph.D. Researcher South Ural Scientific Centre Mineralogy and Environmental Geology of the Ural Branch RАS ▪ Orcid

Abstract

The article reports on the presence of minerals of the crichtonite group (MCG) in ooids of mineralized volcaniclastic rocks of the Rudnogorskoe iron deposit (Eastern Siberia). The ooids are characterized by a concentric-zoned structure of detrital component, expressed in a sequential change of hematite-smectite core → smectite-chlorite → chlorite-garnet → apatite-chlorite zones, which are rimmed by thin-layered magnetite. Rare crystalline MCG aggregates in ooids are found in the peripheral apatite-chlorite zone. Based on the chemical composition and Raman spectra, the MCG are identified as crichtonite and davidite-Ce. The following components are determined in the composition of crichtonite, wt.%: TiO2 63.73-70.69, FeO 18.03-23.58, SrO 2.24-4.03, CaO 2.22-4.10, MgO 0.33-1.02, Al2O3 up to 2.01, MnO up to 0.54 and Ce2O3 up to 1.88. Davidite-Ce typically occurs along the edges of crichtonite and contains, wt.%: TiO2 60.54-62.28, FeO 22.67-25.77, Ce2O3 3.18-5.0, La2O3 2.47-2.74 and SrO 0.58-0.64. The MCG also contain up to 4.69 wt.% UO2. Complex processes of breakdown of MCG and their replacement by anatase are accompanied by the formation of REE (anzaite-Ce) and U (uraninite) minerals and subsequent transformation of anatase to rutile. A sequence of mineral formation of the ooids indicates that the formation and growth of the MCG crystals is a result of lithification of accumulated Ti and trace elements during smectitization of basaltic clasts. Further processes of mineral transformation are associated with the transformation of crichtonite to simple Ti oxides and the precipitation of REE and U minerals. Titanite is a product of the final skarn stages of ore formation.

Funding

The research was carried out within the framework of the project by the Russian Science Foundation N 22-17-00215. The studies are based on material collected during field works, which were supported by state contract of SUSC MEG UB RAS N 122031600292-6.

Introduction

Minerals of the crichtonite group (MCG) are complex oxides with general structural formula XIIAVIBIVT2VIC18(O, OH, F)38, where XIIA = K, Ba, Sr, Ca, Na, La, Ce, Pb; VIB = Mn, Y, U, Fe, Zr, Sc; VIC18 = Ti, Fe, Cr, V, Nb, Mn, Al and IVT2 = Fe, Mg, Zn, Mn (Roman numerals are the coordination numbers of cations) [1-3]. They systematically contain only Ti, Fe and O, and 10 to 16 Ti atoms per formula [2]. The MCG include more than 16 approved mineral species. According to the predominance of large cations (position A), the MCG include crichtonite (Sr), loveringite (Ca), landauite (Na), davidite (U+REE), senaite (Pb), lindsleyite (Ba), matiasite (K) and dessoite (Sr+Pb) [2-4]. The MCG are found as accessory minerals in various igneous, metamorphic, and metasomatic rocks [2, 4]. These unusual minerals, which combine various incompatible elements, are found as inclusions in garnet xenocrysts in kimberlites [4-6], garnet peridotites [7], and metapelites of granulite facies of metamorphism [8], the genesis of which is traditionally associated with processes of mantle metasomatism. The MCG are also known in hydrothermal quartz veins in metasedimentary rocks [9], and Proterozoic massive sulfide ores and metasomatites of the Kola region [10, 11]. In sedimentary strata, brookite, anatase, and rutile containing various trace elements are described as main authigenic Ti oxides [12-14]. The composition of the MCG in assemblage with anatase, rutile and titanite in ooids of the mineralized volcaniclastic rocks from the Rudnogorskoe iron ore deposit (Eastern Siberia) expand our knowledge on the genesis and distribution of this specific mineral assemblage and can serve an indicator of Ti mobilization during the formation of iron ore deposits.

Geological setting of the deposit

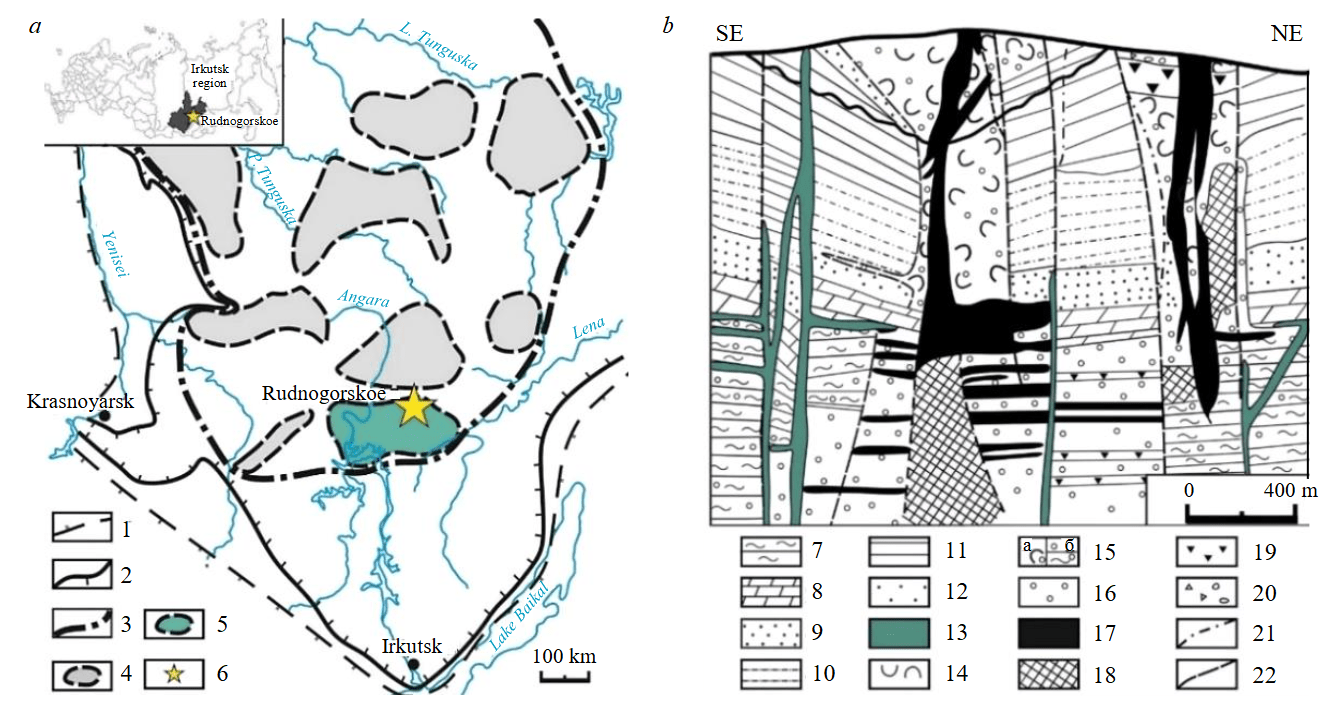

The Rudnogorskoe deposit is one of the largest among the Angara-Ilim iron deposits within the Tunguska depression of Eastern Siberia (Fig.1, a). The geological structure of the region is characterized by widespread occurrence of Cambrian-Ordovician sedimentary and Triassic volcanic-terrigenous rocks [15-17]. Most researchers believe that the mineralization of the Rudnogorskoe deposit, as well as other deposits of the Angara-Ilim iron province, is confined to specific “pipe” structures (“explosion pipes” or “diatremes” extending to a depth of 700-1200 m), which formed during multiphase subalkaline basic volcanism with phreatic processes and periods of calmer gas emission [18]. The ore-bearing “pipes” break through all the stratigraphic levels of the Paleozoic sedimentary strata, forming an extended ring-shaped ore zone on the surface, which is mainly composed of rhythmically layered volcano-sedimentary strata [17]. The formation of a large depression is explained by the release of large volumes of salts from the Lower Cambrian salt-bearing deposits during volcanism and post-volcanic processes [15, 19].

Fig.1. The iron deposits of the Angara-Tunguska province of Eastern Siberia (the inset shows the area of the studied deposit): a – scheme of location of iron deposits with simplifications [20] (1-3 – boundaries: 1 – of the platform fold frame, 2 – sedimentary rocks of the platform cover, 3 – Angara-Tunguska province; 4 – ore regions; 5 – Angara-Ilim region; 6 – location of the deposit); b – geological section of the Rudnogorskoe deposit [21] (7 – Є2-3: siltstone; 8-10 – О1-О3: 8 – dolomite, 9 – quartz sandstone, 10 – claystone and marl; 11, 12 – S1: 11 – claystone and siltstone, 12 – sandstone; 13-19 – C-P1: 13 – dolerite, 14 – volcaniclastic rocks, 15 – volcaniclastic (a) and sedimentary (б) rocks affected by skarn processes, 16 – skarns, 17, 18 – magnetite ores: 17 – Feore content > 25 %, 18 – Feore content 14-25 %, 19 – carbonate rocks with disseminated magnetite; 20, 21 – Q: 20 – alluvium and talus deposits, 21 – eruptive contact; 22 – faults)

The deposit is characterized by the presence of a latitudinal fault with the main ore body ~40 m thick on average, which is traced for a distance of up to 3000 m (Fig.1, b). The ore body crosses the Central pipe, continues in the Western pipe, and is traced in the Ordovician sedimentary rocks outside the pipe structures in the eastern flank of the deposit.

Magnetite ore bodies, mainly represented by massive and banded ores, have a steep (60-80°) dip to a depth of 300-350 m. Further to the depth, the ore bodies are swelled and split on smaller bodies, they are observed outside the pipes and are traced as numerous thin sheet-like bodies, affected by fault zones or dolerite dikes to the next ore body [22]. The ore bodies are hosted in volcaniclastic rocks (often with sedimentary detrital material), the size of clasts of which varies from a millimeter to a few centimeters, less often to several tens of centimeters [23]. Disseminated magnetite ores are abundant in the deeper horizons of the pipes. Some authors [24] consider that the deep channels of the pipes are the ore-feeding structures and that the deposition of magnetite is related to hydrothermal fluids. According to other researchers, the magnetite bodies represent mineralized beds of volcano-sedimentary rocks, which were removed from the horizontal position as a result of shear deformations [22], or are the products of sedimentogenesis and diagenesis of volcaniclastic material, which was transformed by metasomatic processes [25].

The Rudnogorskoe deposit was discovered in the early 1930s by the East Siberian Geological Management. In 1949-1956, the Rudnogorskaya Geological Exploration Expedition, which was organized by the Ministry of Geology of the USSR, restarted exploration and prospecting-evaluation works interrupted by a war and estimated the ore reserves (290.4 Mt). Till the middle of the 1980s, works were aimed at additional exploration of deep horizons and flanks of the deposit and preparation of the deposit for open-pit mining. Since 1982, the Rudnogorskoe deposit has been mined by an open pit, the depth of the open pit is currently about 250 m. In the deposit, the magnetite ores are characterized by various textural varieties (massive, banded, oolitic, crustification, plicated, thin-platy, schistose, breccia, conglomerate, reniform), which are found together and have complex relationships [23]. The oolitic magnetite ores are of special interest, because they rarely form in endogenic conditions. They occur as small lenticular bodies among abundant banded magnetite ores and are concordant to banding (bedding). The oolitic structures are also characteristic of banded and massive ores. The identification of the formation conditions of ooids in magnetite ores of the deposit is therefore important for understanding the ore formation process. The study and recognition of unknown accessory mineralization in ooids can be helpful for the consideration of genetic issues of ore formation processes.

Analytical methods

Samples of magnetite ores and mineralized volcaniclastic rocks were collected during the field works in the open pit of the Rudnogorskoe deposit. All studies were conducted at the SUSC MEG UbRAS. The mineral composition of ores was studied on an Olympus BX51 optical microscope. The chemical composition of minerals was analyzed on a Tescan VEGA 3 SBU scanning electron microscope equipped with an Oxford Instruments X-act energy-dispersive spectrometer. The detection limit of SEM-EDS analysis is no more than 0.1 wt.%. The reproducibility of analyses varies from 1 to 15 rel.%.

The Raman spectra of minerals were registered on a iHR320 HORIBA JOBIN Yvon Raman spectrometer equipped with an Olympus BX41 microscope, a TV camera and a cooled CCD detector (He-Ne laser, Pmax – 20 mW, l = 632.8 nm). The spectra were collected in 180° geometry in a range of 100-2000 cm–1 and represent a combination of 20 intermediate spectra with an accumulation time of 30 s. The spectra were recorded from zones of 10 μm in size. The MCG, as well as other minerals (saponite, titanomagnetite, hematite, chlorite, anatase, brookite, rutile), were identified by comparison with published data and RRUFF database [26].

The trace element content of MCG was determined using LA-ICP-MS analysis on an Agilent 7700x mass spectrometer equipped with a New Wave Research UP-213 laser ablation system at a laser beam diameter of 20 μm, a speed of 10-15 μm/s, an energy of 3-4 J/cm2, and a frequency of 7 Hz, and carrier gases of He (0.6 l/min) and Ar (0.95 l/min). The international standards of synthetic basalt glasses USGS GSD-1G and NIST SRM 610 were used for calibration and calculation.

Results

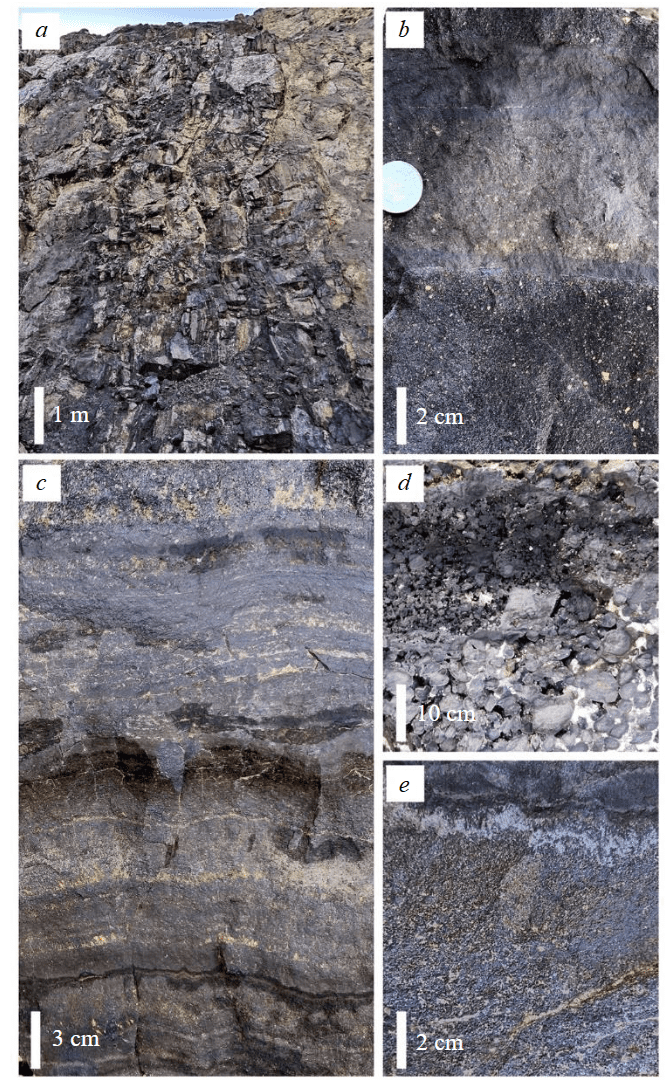

Position of the mineralized volcaniclastic rocks. A steeply dipping magnetite ore body up to ~30 m thick with a consistent strike was exposed in the open-pit of the deposit. The ore body has contact with a nearly conformable horizon of volcaniclastic rocks (Fig.2, a), which gradually transit to magnetite ores. The ores are characterized by massive, banded, thin-laminated and breccia-like textures, which chaotically replace each other. The thickness of these bands varies from a few centimeters to a few meters. The dominant banded ores represent an alternation of beds a few millimeters to 10-20 cm thick consistent along the strike and dip, which are composed of variously granular magnetite, locally, with a minor amount of hematite, chlorite, apatite and calcite. Some intervals of the ore body exhibit alternation of beds of magnetite ores and volcaniclastic rocks (Fig.2, b). The volcaniclastic beds are characterized by a varying degree of replacement by magnetite up to the formation of monomineral magnetite beds with relics of rare volcanic clasts. The thicker massive bands of magnetite ores without relics of detrital material are characterized by coarse-banded structure. Massive ores are often replaced by fine-banded ores, the structure of which resembles fine bedding with typical wavy textures and interbeds of gangue material (Fig.2, c). The oolitic ores occur as small thin lenticular bodies (1.0×3.0 m), which show a successive change in size of the oolitic material (Fig.2, d). In some intervals of the ore body, massive and banded ores are also composed of magnetite ooids in the magnetite matrix (Fig.2, e).

Fig.2.Textures of magnetite ores: a – gradual contact of magnetite ores with volcaniclastic rocks; b – banded magnetite ore; c – thin-bedded magnetite ore; d – gradation-bedded oolitic ore; e – massive oolitic bed. Photos of the open-pit wall

The mineralized volcaniclastic rocks have contact with the ore body in the northwestern part of the open pit. The clasts of these rocks are characterized by the ooid morphology: smoothed-angular and angular dark gray, light gray and greenish gray clasts are enveloped and replaced by a magnetite rim of a varying thickness (Fig.3, a). The thickness of the magnetite rim varies from < 1 mm up to the formation of concentric-zoned magnetite ooids often with relics of detrital material in the core. The ooid-supported matrix consists of magnetite, calcite and chlorite. All stages of the transformation of rock clasts from the formation of the magnetite rim to the transformation to magnetite ooid are often observed even within one sample.

Internal structure of the ooids. The angular clasts with zig-zag boundaries in ooids have glassy structure and are rimmed by magnetite (Fig.3, a). The size of the clasts varies from a few millimeters to 1 cm. In most cases, almost fine spherical to ellipsoidal clasts are transformed to zoned magnetite ooids. The matrix between the ooids is typically heterogeneous and is enriched in magnetite.

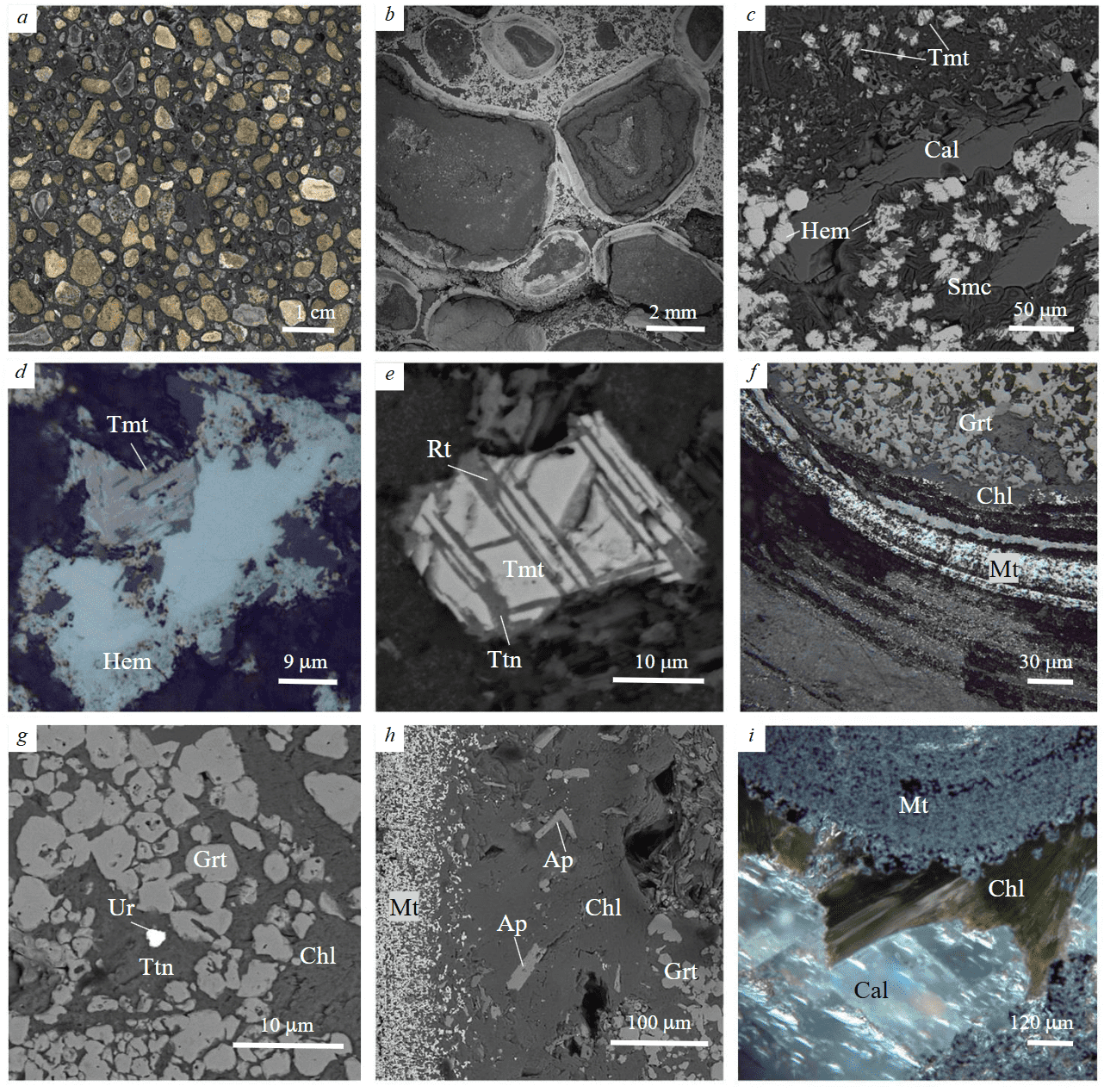

Fig.3. Mineral composition of ooids of volcaniclastic rocks: a – volcaniclastic rock; b – concentrically-zoned structure of volcaniclastic fragments in ooids; c – hematite (Hem)-smectite (Smc) core of the ooids, Cal – calcite veinlets; d – replacement of titanomagnetite (Tmt) by hematite in the core; e – decomposition of titanomagnetite with precipitation of rutile (Rt) and titanite (Ttn) in the smectite-chlorite zone; f – chlorite–garnet (Grt), apatite (Ap)-chlorite (Chl) and magnetite (Mt) zones; g – inclusion of uraninite (Ur) in titanite of chlorite-garnet zone; h – apatite crystals in chlorite zone; i – chlorite on the surface of ooids. Polished sample (а); BSE image (b, c, e, g, h); reflected light (d, f, i), dark-field image (i)

The clasts of the ooids are characterized by concentric-zoned structure represented by the alternation of zones with different mineral composition (Fig.3, b). The most complete zonation includes a core composed of hematite-smectite aggregate, which is successively rimmed by smectite-chlorite, chlorite-garnet (andradite-grossular series), and apatite-chlorite zones and a thin inner magnetite rim.

Smectite in the ooid core occurs as curved variously oriented fine-flaky aggregates and corresponds in composition to saponite Ca0.11-0.41(Fe2+0.50-0.57Mg2.36-2.67)2.9-3.2(Si3.37-3.63Al0.39-0.59)4.00 O10(OH)2.0×n(H2O). It is associated with Ti-bearing hematite (up to 1.15 wt.% TiO2), which replaces numerous titanomagnetite grains (Fig.3, c, d). Hematite forms rounded (spherulitic) aggregates, which are characterized by concentric-zoned structure: massive hematite in the center of spherulites is rimmed by radial-fibrous hematite. With the distance from the core, hematite disappears and smectite is replaced by saponite-Mg-chlorite-1 mixed-layered aggregates, which contain uneven dissemination (size up to 30 μm) of partly decomposed titanomagnetite (Fig.3, c). Mg-chlorite-1 (Mg3.27-5.00Fe0.35-0.98Al0.42-0.65Ca0.04-1.45)5.97-6.10(Si3.26-3.45Al0.55-0.74)4.00O10(OH)8 corresponds to clinochlore. The titanomagnetite grains in chloritized matrix have uneven contours, are characterized by regularly oriented lamellar rutile plates and the formation of titanite along the edges (Fig.3, e).

The chlorite-garnet zone consists of rounded and angular grains of garnet of the andradite–grossular series up to 0.2-0.3 mm in size, which are enclosed in mica-like high-Mg chlorite-2 (Mg5.27-5.61Fe0.00-0.27Al0.39-0.59)6.03-6.19(Si3.20-3.25Al0.75-0.88)4.00O10(OH) (Fig.3, f). Rare titanite aggregates with rutile and uraninite inclusions are observed in this zone (Fig.3, g). The chlorite-garnet zone transit to a narrow chlorite zone (Mg-chlorite-2), with numerous apatite crystals (Fig.3, h). The chlorite zone gradually transits to the outer magnetite zone, which represents a thin rhythmic intercalation of mostly magnetite and chlorite (Mg-chlorite-2) layers (Fig.3, f). The outer chlorite-magnetite zones are typically thinner that the ooid core and are characterized by calcite and Mg-Fe-chlorite-3 veinlets. The matrix consists of coarse-grained carbonate-chlorite-magnetite mass, where ooids are overgrown by coarse-flake Mg-Fe-chlorite-3 (Fig.3, i).

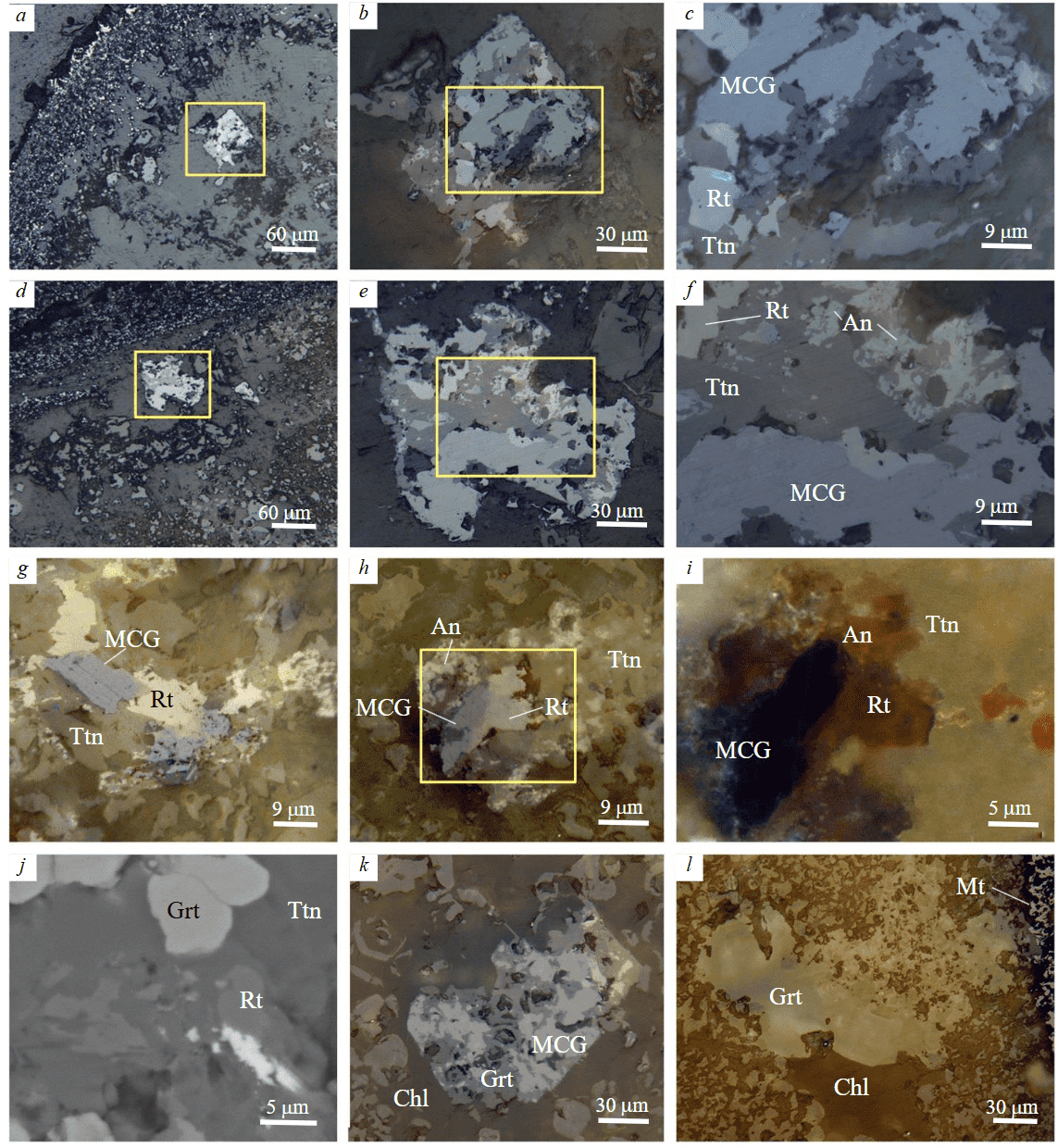

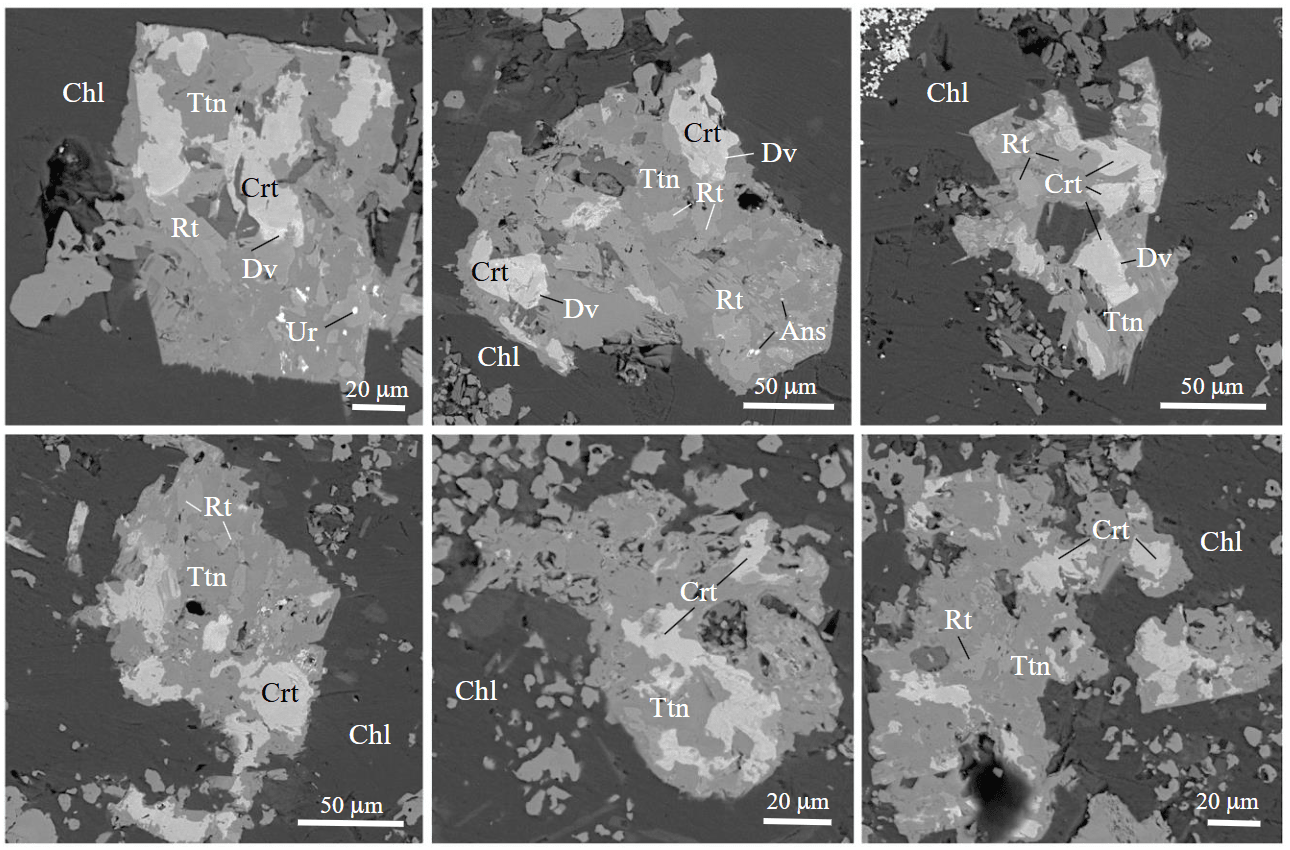

Minerals of the crichtonite group. Rare euhedral to subhedral crystals of Ti oxides with the size of 50 to 150 µm were found in apatite-chlorite zone of the ooids (Fig.4, a, d). They often lose crystallographic edges and acquire sinuous outlines with bay-shaped torn contours (Fig.4, g).These crystals have complex inner structure in reflected light, which is characterized by disordered distribution of variously colored grains in titanite mass (Fig.4, b, c, e, f). Minerals, which are bluish gray color in reflected light (Fig.4, a-h) and opaque dark brown, almost black in dark-field image (Fig.4, i), are attributed to the MCG. These grains are often rimmed by a narrow discontinuous marginal zone of paler minerals. The MCG are closely associated with bright blue anatase aggregates and gray rutile in reflected light and orange-yellow in dark-field image (Fig.4, i). In some samples, the MCG are replaced by anatase and the latter is replaced by rutile (Fig.4, f, i). Anatase contains relic crichtonite and uraninite inclusions. In many cases, only titanite with relic rutile inclusions is preserved in ooids (Fig.4, j). In ooid clasts of mostly garnet-chlorite composition, the MCG are replaced by Ti-bearing garnet (up to 3-4 wt.% TiO2) (Fig.4, k, l).

Fig.4. Minerals of the crichtonite group in ooids: a, d – position of the MCG crystals in chlorite zone; b, c, e, f – details of Figs. a and d: heterogeneous inner structure of crystals and replacement of MCG by anatase (An) (blue)

and anatase by rutile (gray); g – relationship of MCG and rutile aggregates in titanite with uneven contours; h – replacement of MCG by anatase-rutile aggregates; i – detailed dark-field image of Fig. h; j – rutile relics with inclusions of an unidentified Ce-mineral (white) in titanite; k – replacement of the MCG-rutile aggregates by garnet; l – Ti-bearing garnet pseudomorphosis by MCG in chlorite mass; a-i, k, l – reflected light (i – dark-field image); j – BSE images

Symbols of minerals see in Fig.3

Chemical composition of the MCG. The TiO2 content of the MCG covers almost the entire range of concentrations, varying from 60.54 to 70.59 wt.%. The main components of their composition include SrO, CaO, MnO, Ce2O3, La2O3 and UO2 (Fig.5, Table 1) followed by subordinate MgO and Al2O3 and, locally, SiO2. Three groups of complex Ti oxides are distinguished based on optical properties and chemical composition.

Fig.5. Minerals of the crichtonite group: Crt – crichtonite; Dv – davidite-Ce; Ans – anzaite-Ce; U – uraninite; Rt – rutile; Ttn – titanite; Chl – chlorite. BSE images

Group 1 includes bluish gray minerals in reflected light, which contain, wt.%: TiO2 63.73-70.69, FeO 18.03-23.58, SrO 2.24-4.03, CaO 2.22-4.10, MgO 0.33-1.02 and, locally, (up to) Al2O3 2.01, MnO 0.54, Ce2O3 1.88, La2O3 1.21 and UO2 0.94 (Table 1). The change in the mineral color is due to variations in the MnO and Ce2O3 contents up to their complete absence. The structural formula of the mineral recalculated to 38 O atoms is (Sr0.34-0.48Сa0.26-0.45Ce0-0.20La0-0.13)1.00(Ca0-0.79U0-0.06) Fe2.00-2.87(Ti3.92-15.04Fe1.88-3.12Mg0.14-0.43Mn0-0.13Al0-0.67Si0-0.34)17.14-17.99O38, which allows us to ascribe this mineral to crichtonite. The formulas of crichtonite indicate that the “large cations” (Sr and Ce) in the mineral structure fully occupy site A (M0) together with subordinate Ca, whereas U with Ca enters site B (M1).

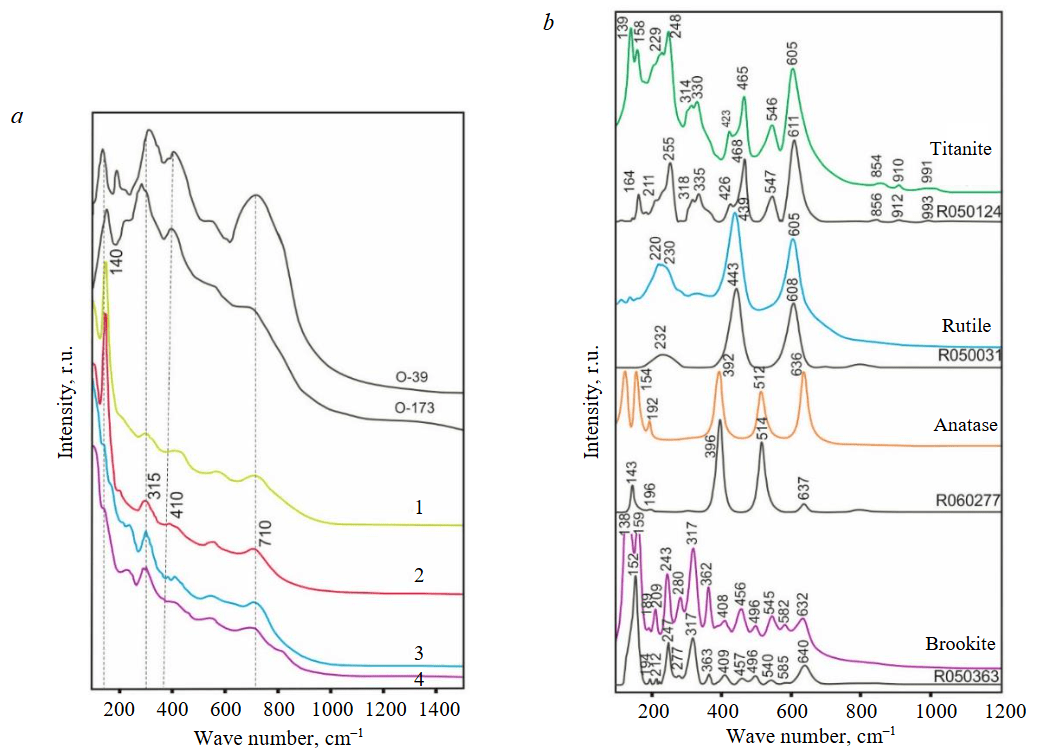

The Raman spectra of the MCG in a range of 100-1400 cm–1 also confirm the presence of crichtonite (Fig.6, a). The main peaks of crichtonite are localized in the ranges of 710-720, 130-200, 300-315, and 410-440 cm–1. In spite of similar shape of spectra of the studied phases, the position of main peaks can be different due to the different content of trace elements in crichtonite.

Group 2 of the MCG includes the mineral phases that form narrow marginal zones or “lenses” around crichtonite with fine uraninite inclusions. Compared to crichtonite, they show a lower content, wt.%: TiO2 60.54-62.28 and SrO 0.58-0.64, and a higher content of FeO 22.67-25.77 and Ce2O3 3.18-5.20 at the constant presence of La2O3 2.47-2.74 and, locally, UO2 up to 4.69. The mineral formula recalculated to 38 O atoms is (Ce0.35-0.56La0.26-0.31Sr0.07-0.10Сa0.08-0.19)Ca0.39-0.71Fe2.00 (Ti13.44-13.92Fe3.07-3.72Mg0.20-0.27Si0-0.21Al0-0.41Si0-0.21)17.38-17.77O38, which is typical of davidite-Ce. No high-quality Raman spectra of davidite-Ce were registered because of numerous uraninite inclusions.

Table 1

Chemical composition of Ti minerals, wt.%

|

TiO2 |

FeO* |

CaO |

MgO |

MnO |

Al2O3 |

SiO2 |

SrO |

Nb2O3 |

La2O3 |

Ce2O3 |

UO2 |

∑ |

Formulas |

|

Crichtonite |

|||||||||||||

|

70.69 |

18.21 |

4.10 |

0.39 |

0.42 |

– |

– |

2.95 |

– |

– |

1.03 |

– |

97.79 |

(Sr0.44Ce0.11Ca0.45)1.00Ca0.79Fe2.00(Ti15.04Fe1.88Mg0.16Mn0.10)17.18O38 |

|

66.85 |

18.03 |

3.48 |

0.53 |

0.54 |

– |

1.16 |

2.83 |

– |

0.84 |

1.78 |

0.89 |

96.93 |

(Sr0.43Ce0.19La0.09Ca0.29)1.00(Ca0.79U0.06)0.85Fe2.00(Ti14.52Fe1.92Si0.34Mg0.23Mn0.13)17. 14O38 |

|

63.73 |

23.37 |

2.22 |

0.66 |

0.40 |

0.58 |

– |

3.10 |

0.23 |

1.11 |

1.30 |

0.94 |

97.64 |

(Sr0.48Ce0.14La0.12Ca0.26)1.00(Ca0.43U0.06Nb0.02)0.51Fe2.00(Ti13.96Fe3.12Mg0.29Al0.20Mn0.10)17.66O38 |

|

66.12 |

22.82 |

2.66 |

1.02 |

0.34 |

0.97 |

– |

2.98 |

– |

– |

1.32 |

– |

98.23 |

(Sr0.45Ce0.14Ca0.41)1.00Ca0.40Fe2.00(Ti14.11Fe2.87Mg0.43Al0.32Mn0.08)17.83O38 |

|

66.84 |

21.88 |

1.37 |

0.49 |

0.75 |

0.23 |

– |

4.03 |

0.28 |

– |

1.41 |

0.92 |

98.20 |

(Sr0.61Ce0.15Ca0.24)1.00(Ca0.18U0.06Nb0.03)0.29Fe2.00(Ti14.47Fe2.74Mg0.21Mn0.18Al0.08)17.68O38 |

|

65.04 |

21.91 |

2.72 |

0.86 |

0.37 |

2.01 |

– |

2.26 |

– |

1.21 |

1.88 |

– |

98.26 |

(Sr0.34Ce0.20La0.13Ca0.33)1.00Ca0.50Fe2.00(Ti13.92Fe2.69Al0.67Mg0.36Mn0.09)17.74O38 |

|

67.56 |

21.83 |

3.47 |

0.54 |

– |

0.55 |

0.42 |

2.59 |

– |

– |

0.90 |

– |

97.25 |

(Sr0.39Ce0.09Ca0.52)1.00Ca0.53Fe2.00(Ti14.36Fe2.64Mg0.23Al0.18Si0.12)17.53O38 |

|

66.93 |

22.10 |

3.11 |

0.77 |

– |

1.12 |

– |

2.24 |

– |

– |

0.85 |

– |

97.12 |

(Sr0.34Ce0.09Ca0.57)1.00Ca0.38Fe2.00(Ti14.30Fe2.73Al0.38Mg0.33)17.73O38 |

|

68.93 |

19.98 |

3.74 |

0.41 |

– |

0.46 |

– |

2.78 |

– |

– |

0.99 |

0.42 |

97.77 |

(Sr0.42Ce0.10Ca0.48)1.00(Ca0.66U0.03)0.69Fe2.00(Ti14.71Fe2.27Mg0.17Al0.15)17.31O38 |

|

69.22 |

20.59 |

3.53 |

0.33 |

– |

0.32 |

– |

2.80 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

96.79 |

(Sr0.42Ca0.48)1.00Ca0.50Fe2.00(Ti14.80Fe2.40Mg0.14Al0.11)17.45O38 |

|

69.28 |

21.45 |

3.86 |

0.49 |

– |

0.44 |

– |

2.63 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

98.14 |

(Sr0.39Ca0.61)1.00Ca0.55Fe2.00(Ti14.62Fe2.53Mg0.20Al0.15)17.50O38 |

|

67.05 |

23.58 |

2.32 |

0.64 |

– |

1.76 |

– |

2.49 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

97.85 |

(Sr0.39Ca0.70)1.07Fe2.00(Ti14.16Fe2.98Al0.58Mg0.27)17.99O38 |

|

Davidite-Ce |

|||||||||||||

|

60.71 |

23.91 |

2.5 |

0.61 |

0.32 |

0.56 |

0.71 |

0.64 |

– |

2.38 |

5.2 |

– |

97.54 |

(Ce0.56La0.26Sr0.10Ca0.08)1.00Ca0.71Fe2.00(Ti13.44Fe3.30Mg0.27Si0.21Al0.19Mn0.08)17.49O38 |

|

60.54 |

25.77 |

1.87 |

0.50 |

– |

1.17 |

– |

0.65 |

– |

2.47 |

3.95 |

– |

96.91 |

(Ce0.43La0.27Sr0.10Ca0.08)1.00Ca0.39Fe2.00(Ti13.43Fe3.72Al0.41Mg0.22)17.77O38 |

|

60.97 |

23.30 |

2.70 |

0.57 |

– |

– |

– |

0.58 |

– |

2.74 |

3.69 |

0.86 |

95.42 |

(Ce0.41La0.31Sr0.09Ca0.19)1.00(Ca0.68U0.06)0.74Fe2.00(Ti13.83Fe3.29Mg0.26)17.38O38 |

|

62.28 |

22.67 |

2.25 |

0.45 |

– |

0.84 |

– |

0.44 |

– |

– |

3.18 |

4.69 |

96.71 |

(Ce0.35Sr0.07Ca0.58)1.00(U0.31Ca0.14)0.45Fe2.00(Ti13.92Fe3.07Al0.29Mg0.20)17.48O38 |

|

Anatase |

|||||||||||||

|

88.67 |

5.30 |

1.25 |

– |

– |

– |

0.68 |

0.08 |

– |

– |

– |

0.62 |

96.60 |

(Ti0.94Fe0.06Ca0.02Si0.01Sr0.001U0.002)1.02O2 |

|

Rutile |

|||||||||||||

|

96.20 |

2.62 |

0.79 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

0.46 |

– |

– |

– |

100.07 |

(Ti0.97Fe0.03Ca0.01Nb0.002)1.01O2 |

|

98.34 |

0.51 |

0.55 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

0.56 |

– |

– |

– |

99.97 |

(Ti0.99Fe0.01Ca0.01Nb0.002)1.01O2 |

|

Titanite |

|||||||||||||

|

35.7 |

0.75 |

28.23 |

– |

– |

2.81 |

31.69 |

– |

– |

– |

1.16 |

– |

100.35 |

(Ca0.98Ce0.01)0.99(Ti0.87Al0.11Fe0.02)1.00Si1.03O5 |

|

34.42 |

0.67 |

28.83 |

– |

– |

3.74 |

32.23 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

99.88 |

Ca1.00(Ti0.84Al0.14Fe0.02)1.00Si1.04O5 |

|

37.18 |

1.23 |

28.99 |

– |

– |

0.97 |

31.82 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

100.2 |

Ca1.01(Ti0.91Al0.04Fe0.03)0.98Si1.03O5 |

|

37.84 |

0.76 |

28.52 |

– |

– |

2.64 |

31.95 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

101.7 |

Ca0.97(Ti0.91Al0.10Fe0.02)1.03Si1.02O5 |

Note. The formulas are recalculated to 2, 5, and 38 oxygen atoms for anatase and rutile, titanite, and crichtonite and davidite-Ce, respectivly; *– iron is accepted as Fe3+.

Group 3 of minerals represents fine inclusions (up to 3-5 μm) in anatase, rutile and, locally, in titanite. Their chemical composition, wt.%: Ce2O3 21.82, La2O3 8.33, Pr2O3 2.01, Nd2O3 5.04, TiO2 36.99 is close to the composition of anzaite-Ce with formula (Ce2.18Nd0.85La0.41Pr0.26)4.15 Ti5.68O18(OH)2 (based on 18 O atoms and two OH groups). Crichtonite is decomposed with the formation of anatase, which is further transformed to rutile (Table 2). Rutile contains, wt.%: CaO 0.55-0.79, FeO 0.51-2.62 and rarely Nb2O5 0.46-0.56. The Raman spectra of simple Ti oxides show the presence of both anatase and brookite (Fig.6, b). The chemical composition of titanite is heterogeneous due to varying FeO and Al2O3 contents; some analyses exhibit the presence of Ce2O3 (see Table 1).

Fig.6. Raman spectra of Ti minerals in ooids: а – spectra of crichtonite (1-4) in comparison with spectra of crichtonite (O-39, O-173) from [6]; b – spectra of rutile, anatase, brookite, and titanite in comparison with spectra from the RRUFF database [26]

Table 2

Trace elements of the crichtonite-anatase-rutile aggregates, ppm

|

Elements |

Contents |

Elements |

Contents |

||||||||

|

Ti |

28.7 |

27.25 |

13.91 |

28.5 |

21.97 |

Nb |

890 |

857 |

290 |

713 |

952 |

|

Fe |

5.45 |

2.13 |

7.28 |

10.25 |

1.1 |

Ba |

1410 |

626 |

340 |

1760 |

220 |

|

Si |

8.38 |

10.06 |

13.5 |

13 |

10.77 |

Th |

202 |

104 |

54.5 |

322 |

245 |

|

Ca |

9.15 |

11.58 |

16.8 |

10.24 |

16.52 |

U |

3520 |

1630 |

636 |

3390 |

757 |

|

Na |

350 |

336 |

92 |

521 |

174 |

La |

3940 |

573 |

401 |

2860 |

638 |

|

Mg |

830 |

2040 |

3240 |

3060 |

2040 |

Ce |

5250 |

2030 |

1203 |

5340 |

2180 |

|

Al |

3030 |

8060 |

18200 |

2860 |

6130 |

Pr |

442 |

365 |

153.6 |

590 |

335 |

|

V |

382 |

481 |

714 |

325 |

318 |

Nd |

1418 |

1580 |

545 |

1990 |

1478 |

|

Cr |

16 |

12 |

83 |

22 |

25 |

Sm |

245 |

301 |

105 |

271 |

260 |

|

Mn |

1549 |

249 |

265 |

1754 |

60 |

Eu |

88 |

87.8 |

39.9 |

108 |

93.1 |

|

Co |

2.9 |

1.98 |

0.88 |

37.9 |

2.4 |

Gd |

203 |

239 |

82 |

246 |

223 |

|

Ni |

0.7 |

2.9 |

1 |

6.8 |

0.6 |

Tb |

32.7 |

31.1 |

10.7 |

30.7 |

28.1 |

|

Zn |

168 |

133 |

29 |

315 |

34 |

Dy |

144 |

156 |

75 |

149 |

148.3 |

|

Ga |

21.6 |

11.8 |

9.8 |

25.1 |

15.9 |

Ho |

24.4 |

22.7 |

12.2 |

24.8 |

22.2 |

|

Sr |

8300 |

670 |

341 |

13030 |

268 |

Er |

67.9 |

51.3 |

29.2 |

50.2 |

35.2 |

|

Y |

459 |

419 |

276 |

426 |

366 |

Tm |

5.9 |

4.9 |

4.12 |

4.83 |

2.96 |

|

Zr |

881 |

779 |

996 |

207 |

349 |

Yb |

24.4 |

23.4 |

26.5 |

16.8 |

17.7 |

|

Lu |

2.86 |

1.75 |

2.87 |

1.83 |

1.25 |

||||||

Note. LA-ICP-MS analyses; Ti, Fe, Si, Ca – wt.%

LA-ICP-MS studies. The crichtonite-anatase-rutile aggregates contain high and varying contents of the following elements, ppm: Sr 268-13030, U 757-3520, Mn 60-1754, V 318-714, Zr 207-996, Y 276-459, Nb 290-952, Ba 220-176, Zn 29-315, Na 92-521 and Th 54.5-322 (Table 2). The high contents, wt.%: Si 8.38-13.50 and Ca 9.15-16.80 are probably related to the entrapment of titanite. The crichtonite-rutile aggregates also exhibit the high REE contents (∑REE 2678-12832 ppm) including high content, ppm: La 401-3940, Ce 1203-5340, Nd 545-1990 and Pr 154-590 (Table 2).

Discussion

Matter source for ooids. The origin of oolitic ores of the Angara-Ilim region is explained by various processes: the metasomatic replacement of carbonate ooliths and their fragments, which inherit concentric-zoned structure; limestones with massive, banded and other textures and silicate clasts and the precipitation of ooids directly from hydrothermal fluids [23, 27]. Note that many issues of the formation of both ooids and magnetite ores of this area, which are confined to an intracontinental rift zone [22], are still a matter debate and are reconsidered due to the accumulation of new factual material. Our material reflects the ideas about pre-skarn (sedimentary) and skarn stages of ore formation [23-25]. The ore textures indicate that the magnetite ores formed as a result of transformations of volcaniclastic rocks with accumulation of Fe similarly to some sedimentary Fe deposits [28]. The horizontally bedded structure, locally, asymmetric gradational structure of ore beds and gradual or sharp transition to adjacent barren beds are one of the most important morphological arguments for the deposition of volcaniclastic material and ore mud in a water basin. The steep occurrence of the ore body can be interpreted as sliding of volcano-sedimentary deposits and ore bodies into the “pipe” structures with the formation of steep folds and violation of initial horizontal bedding [22]. The transformation of the precursor hematite ores to magnetite is related to later hydrothermal fluids circulated during skarn processes [23]. However, the authors also suggest other styles of metasomatosis and deposition of ores.

The structural and textural features and mineral composition of detrital material of ooids correspond to smectitized basaltic clasts, which consist of products of the decomposed volcanic glass with rare inclusions of calcic plagioclase and interstitial titanomagnetite, characterized by a higher FeO+Fe2O3 (up to 20 wt.%) and TiO2 (2,0-2,5 wt.%) content [22, 23]. The saponite-hematite core of the ooid clasts resembles mineral assemblages, which form during the transformation of basaltic glass to saponite accompanied by the formation of Fe minerals under low-temperature interaction with seawater [29]. Colloidal hematite in assemblage with saponite in the ooid core can be important evidence of primary Fe oxy-hydroxides during their formation. The formation of zoned magnetite and chlorite-magnetite zones around detrital grains, which often occurred together with their replacement, can be explained by the ooid growth due to absorption of ferrous and clayey material (due to hydrolysis and dissolution of volcanic material) on fine-dispersed and high-porous decomposition products of volcanic glass in the conditions of a local isolated highly saline basin characterized by frequently repeated sediment rolling due to pulsated gas emissions. The presence of the deformed ooids is evidence of their soft state at the burial time and, therefore, of their primary formation. Similar mineral composition of the ooids and matrix of volcaniclastic rocks indicates that the fluid composition remained constant from the moment of the formation of ooids to the precipitation of matrix.

The sequential character of authigenic mineral transformations, which is characterized by successive replacement of saponite in the ooid core to chlorite at the periphery of detrital material, indicates alterations related to later hydrothermal fluids. In some cases, the changes affected the periphery of the clasts, while in other cases the decomposition of clasts is stronger, when their central parts are replaced by chlorite and garnet. The evolutionary series of transformations of Mg-chlorite of similar composition Altotal < 2.2 and KFe = 0-0.30, где Altotal = AlIV + AlVI, KFe = Fe/(Fe + Mg) is characteristic of chlorite from salt-bearing basins [30], which is consistent with the participation of gas-saturated brine Cl-Mg waters in ore formation processes, which are supplied from the Lower Cambrian salt-bearing units [24]. The formation of the magnetite-chlorite rim and the replacement of clasts by magnetite are attributed to the final skarn stages of ore formation.

Formation sequence of Ti minerals. Titanomagnetite in the ooid clasts is a relic mineral, which occurs in weakly altered (smectitized) glassy groundmass of the core and is replaced by Ti-bearing hematite (up to 1.15 wt.% TiO2) (see Fig.3, d). The presence of the lattice lamella in titanomagnetite can indicate the early magmatic oxidation of ilmenite in primary substance of basaltic clasts. The replacement of titanomagnetite by hematite is explained by low-temperature oxidation of Fe2+ to Fe3+ and its partial removal in the oxidized alkaline conditions of the transformation of clasts of tholeiitic basalts. It is reported that titanomagnetite transits to titanomaghemite and further titanohematite during initial stages of low-temperature basalt – seawater interaction, when the silicate part of the rock still weakly reacts with seawater [31, 32].

Affected by aggressive alkaline waters, Ti, which is released during smectitization of basalts, could accumulate as heterogeneous colloidal gel (TiO2 × nH2O) due to its low mobility and could be retained by smectitized amorphous matter. It is believed that basaltic glasses are altered with the removal of most elements and accumulation of Fe and Ti on the glass surface [30, 33]. It is known, for example, that Ti can be released from pore fluids in form of Ti(OH)4 and precipitate as fine-dispersed TiO2 during the dehydration of sediments [34]. It is suggested that the accumulated TiO2 gel in ooids is an excellent sorbent facilitating the selective fixation of elements of the decomposed basaltic glass. According to [35], the sorption capacity of aqueous Ti hydroxide TiO2 × 9H2O for the uranyl ion UO22– is 2.43∙10–4 mole/g, which is equal to 5.88 wt.% U.

The lithification of smectitized material was accompanied by collective crystallization of trace element-enriched metastable fine-dispersed TiO2 aggregates in pores between the detrital component and authigenic Fe rim. The Fe oxy-hydroxide rim around the rock clasts could prevent the removal of trace elements from the ooids [36]. The presence of brines was favorable for rapid crystallization of authigenic Ti oxides of more complex composition and their growth in weakly consolidated sediments [37]. Thus, the MCG result from recrystallization of clusters of fine-dispersed TiO2 aggregates enriched in trace elements. It is considered that the high Sr content reflects the final stages of basalt – seawater interaction at low (<50) water – rock ratios and the enrichment of gel-like Ti phases in Sr [38]. The release of excess components in form of mineral phases (anzaite-Ce, uraninite) is related to the replacement of the MCG by anatase and later by most stable rutile. It is known that the anatase-to-rutile transition is thermodynamically favorable at all temperatures, whereas the formation of anatase requires low-temperature alkaline conditions controlled by chemistry of pore waters [39]. The presence of REE oxides apparently facilitates the crystallization of anatase in comparison with rutile [40]. The presence of garnet pseudomorphoses after the MCG indicates the formation of crichtonite before the skarn processes. The crichtonite – rutile assemblage was replaced by titanite during later stages of ore formation related to further concentration of brines, which acquire the properties of hydrothermal fluids leading to metasomatic alteration [15, 20-22].

MCG in various mineral formation conditions. The MCG are the most widespread and well-studied from ultra-high pressure metamorphic rocks, mantle peridotites and pyroxenites [4, 7, 8]. Crichtonite in mantle garnets belong to Cr-titanates (16 wt.% Cr2O3, 58 wt.% TiO2), which are enriched in ZrO2 (up to 5 wt.%), K, Ba, Ca and REE (up to 5 wt.% oxides [4, 7, 8, 41]. The MCG, which are enriched in Al (1.1-4.5 wt.% Al2O3), moderately enriched in Zr (1.3-4.3 wt.% ZrO2) and are Ca-, Sr- and, locally, Ba-dominant based on the occupancy of site A and contain a significant amount of Na and light REE, are described in garnets from kimberlite pipes as stable minerals under lithospheric mantle conditions [5, 6].

Numerous MCG are known in lenses of dolomitized limestones of barite-hematite ores of the Buca della Vena deposit (Italy), which is hosted in phyllitic schists (metamorphism of greenschist facies, 250-340 °C) [2, 9, 42]. The MCG as small flattened rhombohedral crystals in dolomite correspond to dessoite, which can be characterized as an intermediate member between Y, U-crichtonite, wt.%: UO2 2.63-8.74, Y2O3 1.37-2.64 and Sr, Pb-davidite, wt.%: SrO 2.19-2.45, PbO 2.90-3.39 [2, 3]. Quartz-chlorite-sulfide veins of Alpine volcano-sedimentary rocks in western Switzerland contain kleisonite (Pb, Sr)(U4+, U6+)(Fe2+, Zn)2(Ti, Fe2+, Fe3+)18(O,OH)38, a U representative of crichtonite, wt.%: UO2 10.07, UO3 4.12, PbO 9.34 [42]. Closely intergrown abundant diverse MCG (crichtonite, senaite, davidite, lovengite, lindsleyite) were found in a narrow contact zone of massive sulfide ore bodies with hydrothermal-metasomatic altered rocks, often with a skarn mineral assemblage, in the Proterozoic structures of the Kola region (Russia) [10, 11]. These minerals are characterized by high Sc2O3 up to 2.4 wt.% and V2O5 up to 20 wt.% contents [10]. The extremely low Cr2O3 content and the presence of chalcophile elements (Pb, Zn) can therefore be indicators of the formation of MCG from low-temperature hydrothermal fluids.

The Ti source and the origin of Ti minerals (anatase, rutile, brookite, Ti-bearing silicates) in sedimentary rocks are a matter of debate. No complex Ti oxides have been identified in them. There are, however, data on the formation of anatase crystals as a result of crystallization of TiO2 amorphous phases and their further merging to globules and clusters, which reflects the ambient mobilization of Ti, which is released during low-temperature submarine transformation processes of volcanic glass and the formation of Fe oxyhydroxides in both modern [43] and ancient [44] Fe oxide sediments. Anatase contains tens to hundreds ppm of V, U, Pb, and Th and the inclusions of authigenic apatite and REE phosphates are observed in the peripheral parts of the anatase aggregates [44].

In spite of long history of study of iron deposits of the Angara-Ilim region, the Ti mineralogy of ores has not been sufficiently studied. Among the Ti minerals, most works describe titanomagnetite, ilmenite, and rutile as relics of ore-hosting volcaniclastic rocks and skarn titanite [20-24]. The processes of transformations of Ti minerals during the formation of magnetite ores and the MCG have not been characterized. The finding of the MCG in magnetite ores of the Rudnogorskoe deposit is the first in both iron deposits of the Angara-Ilim region and iron formations in general.

Conclusion

The clasts of tholeiitic basalt enriched in trace elements are the matter source for the formation of ooids. The successive transformation of volcanic clasts in ooids from saponite to high-Mg chlorite is revealed. The formation of Ti minerals is related to the decomposition of volcanic glass and titanomagnetite of volcaniclastic rocks during the reaction with gas-saturated brines of a shallow basin and the accumulation of fine-dispersed TiO2 aggregates in smectitized amorphous matter with subsequent crystallization of complex Ti oxides during the lithification of clastic rocks. The minerals of the crichtonite group include crichtonite and davidite-Ce are characterized by complex varying chemical composition. During further dehydration processes, the minerals of the crichtonite group were replaced by intermediate metastable anatase and then rutile followed by the precipitation of anzaite-Ce and uraninite. Titanite in ooids formed due to subsequent metasomatic transformations under the influence of brines, which acted as hydrothermal fluids during basalt intrusions. Our material reflects the geochemical behavior of Ti, which includes the evolution change of its mineral phases during the transformation of primary substrate upon Fe-forming processes. This scenario of formation of mineral assemblages of Ti oxides can be applied to other oolitic iron deposits with minor changes.

References

- Grey I.E., Lloyd D.J. The crystal structure of senaite. Acta Crystallographica Section B: Structural Science, Crystal Engineering, and Materials. 1976. Vol. B32. Part 5, p. 1509-1513. DOI: 10.1107/S0567740876012478

- Orlandi P., Pasero M., Duchi G., Olmi F. Dessauite, (Sr,Pb) (Y,U) (Ti,Fe 3+)20O38, a new mineral of the crichtonite group from Buca della Vena Mine, Tuscany, Italy. American Mineralogist. 1997. Vol. 82. Iss. 7-8, p. 807-811. DOI: 10.2138/am-1997-7-819

- Rastsvetaeva R.K. Crichtonite and Its Family: the Story of the Discovery of Two New Minerals. Priroda. 2020, p. 39-47 (in Russian). DOI: 10.7868/S0032874X20080049

- Haggerty S.E. The mineral chemistry of new titanates from the jagersfontein kimberlite, South Africa: Implications for metasomatism in the upper mantle. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 1983. Vol. 47. Iss. 11, p. 1833-1854.

- Rezvukhin D.I., Malkovets V.G., Sharygin I.S. et al. Inclusions of crichtonite-group minerals in Cr-pyropes from the Internatsionalnaya kimberlite pipe, Siberian Craton: Crystal chemistry, parageneses and relationships to mantle metasomatism. Lithos. 2018. Vol. 308-309, p. 181-195. DOI: 10.1016/j.lithos.2018.02.026

- Alifirova T., Rezvukhin D., Nikolenko E. et al. Micro-Raman study of crichtonite group minerals enclosed into mantle garnet. Journal of Raman Spectroscopy. 2018. Vol. 51. Iss. 9, p. 1493-1512. DOI: 10.1002/jrs.5979

- Vrána S. Mineral inclusions in pyrope from garnet peridotites, Kolín area, central Czech Republic. Journal of Geosciences. 2008. Vol. 53. Iss. 1, p. 17-30. DOI: 10.3190/jgeosci.018

- Ague J.J., Eckert J.O. Precipitation of rutile and ilmenite needles in garnet: Implications for extreme metamorphic conditions in the Acadian Orogen, U.S.A. American Mineralogist. 2012. Vol. 97. Iss. 5-6, p. 840-855. DOI: 10.2138/am.2012.4015

- Mario Luiz de Sá Carneiro Chaves, Luiz Alberto Dias Menezes Filho. Minerais do grupo da crichtonita em veios de quartzo da Serra do Espinhaço (Minas Gerais e Bahia). Geologia USP. Série Científica. 2017. Vol. 17. N 1, p. 31-40. DOI: 10.11606/issn.2316-9095.v17-392

- Karpov S.M., Voloshin A.V., Kompanchenko A.A. et al. Crichtonite group minerals in massive sulfide ores and ore metasomatites of the proterozoic structures of the Kola region. Zapiski Rossiiskogo Mineralogicheskogo Obshchestva. 2016. Vol. 145. N 5, p. 39-56 (in Russian).

- Kompanchenko A.A., Voloshin A.V., Bazai A.V. The Mineral Composition of Paleoproterozoic Metamorphosed Massive Sulfide Ores in the Kola Region (A Case Study of the Bragino Ore Occurrence, Southern Pechenga). Geology of Ore Deposits. 2020. Vol. 62. N 7, p. 618-628. DOI: 10.1134/S1075701520070077

- Parnell J. Titanium mobilization by hydrocarbon fluids related to sill intrusion in a sedimentary sequence, Scotland. Ore Geology Reviews. 2004. Vol. 24. Iss. 1-2, p. 155-167. DOI: 10.1016/j.oregeorev.2003.08.010

- Schulz H.-M., Wirth R., Schreiber A. Nano-Crystal Formation of Tio2 Polymorphs Brookite and Anatase Due To Organic – Inorganic Rock–Fluid Interactions. Journal of Sedimentary Research. 2016. Vol. 86. N 2, p. 59-72. DOI: 10.2110/jsr.2016.1

- Chaikovskiy I.I., Chaikovskaya E.V., Korotchenkova O.V. et al. Authigenic Titanium and Zirconium Minerals at the Verkhnekamskoe Salt Deposit. Geochemistry International. 2019. Vol. 57. N 2, p. 184-196. DOI: 10.1134/S0016702919020046

- Vakhrushev V.A. Halite-magnetite ores of the Siberian platform. Geologiya rudnykh mestorozhdenii. 1981. N 6, p. 100-104 (in Russian).

- Nikulin I.V., Fon-Der-Flaas G.S., Baryshev A.S. Explosion-volcanic basaltic ore-forming systems, the Angara iron-ore province. Geologiya rudnykh mestorozhdenii. 1991. N 3, p. 26-40 (in Russian).

- Fon-Der-Flaas G.S., Permyakov A.A., Speshilov V.M. The Rudnogorsk magnetite deposit – magmatism, structure and mineralization. Geologiya rudnykh mestorozhdenii. 1992. N 2, p. 51-67 (in Russian).

- Kalugun I.A., Tremyakov G.A., Fon-Der-Flaas G.S. Origin of iron ores in traps: formation of an ore-bearing diatreme with a root zone of interaction between basaltic magma and evaporites. Novosibirsk: Obedinennyi institut geologii, geofiziki i mineralogii SO RAN, 1994. Preprint N 4, p. 45 (in Russian).

- Polozov A.G., Svensen H.H., Planke S. et al. The basalt pipes of the Tunguska Basin (Siberia, Russia): High temperature processes and volatile degassing into the end-Permian atmosphere. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 2016. Vol. 441. Part 1, p. 51-64. DOI: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2015.06.035

- Pukhnarevich M.M., Naumov V.B., Bannikova L.A. et al. Genesis of mineral-forming fluids of the Korshunovskoe iron deposit. Geologiya rudnykh mestorozhdenii. 1985. N 6, p. 51-59 (in Russian).

- Kalugin A.S., Kalugina T.S., Ivanov V.I. et al. Iron deposits of Siberia. Novosibirsk: Nauka, 1981, p. 238 (in Russian).

- Platform magnomagnetite formation (on the example of the Angara iron ore province). Ed. by G.S.Momdzhi. Moscow: Nedra, 1976, p. 204 (in Russian).

- Zhuk-Pochekutov K.A. Magnetite oolites of the Rudnogorskoe iron deposit. Geologiya rudnykh mestorozhdenii. 1986. N 4, p. 72-83 (in Russian).

- Mazurov M.P., Grishina S.N., Titov A.T., Shikhova A.V. Evolution of Ore-Forming Metasomatic Processes at Large Skarn Iron Deposits Related to the Traps of the Siberian Platform. Petrology. 2018. Vol. 26. N 3, p. 265-279. DOI: 10.1134/S0869591118030049

- Korabelnikova V.V., Fon-Der-Flaas G.S. On sedimentary nature of the “Patellate” magnetite ores of Neryundinsk and Kapaevsk deposits. Geologiya i geofizika. 1979. N 2, p. 98-107 (in Russian).

- Highlights in Mineralogical Crystallography. Ed. by T.Armbruster, R.M.Danisi. De Gruyter, 2016, p. 201. DOI: 10.1515/9783110417104

- Vakhrushev V.A., Vorontsov A.E. Mineralogy and geochemistry of iron deposits in the south of the Siberian platform. Novosibirsk: Nauka, 1976, p. 199 (in Russian).

- Kalugin A.S. Atlas of textures and structures of volcanogenic-sedimentary iron ores of Altai (sources of matter, conditions and mechanism of deposition, phenomena of diagenesis, epigenesis, and metamorphism of ores). Leningrad: Nedra, 1970, p. 176 (in Russian).

- Kossovskaya A.G., Petrova V.V., Shutov V.D. Mineral associations of palagonitization of oceanic basalts and problems of extraction of ore components. Litologiya i poleznye iskopaemye. 1982. N 4, p. 10-31 (in Russian).

- Drits V.A., Kossowskaya A.G. Clay minerals: Micas, chlorites. Moscow: Nauka, 1991, p. 176 (in Russian).

- Bleil U., Petersen N. Variations in magnetization intensity and low-temperature titanomagnetite oxidation of ocean floor basalts. Nature. 1983. Vol. 301. Iss. 5899, p. 384-388. DOI: 10.1038/301384a0

- Swanson-Hysell N.L., Feinberg J.M., Berquó T.S., Maloof A.C. Self-reversed magnetization held by martite in basalt flows from the 1.1-billion-year-old Keweenawan rift, Canada. Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 2011. Vol. 305. Iss. 1-2, p. 171-184. DOI: 10.1016/j.epsl.2011.02.053

- Walton A.W., Schiffman P., Macpherson G.L. Alteration of hyaloclastites in the HSDP 2 Phase 1 Drill Core: 2. Mass balance of the conversion of sideromelane to palagonite and chabazite. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems. 2005. Vol. 6. N 9. N Q09G19. DOI: 10.1029/2004GC000903

- Banfield J.F., Jones B.F., Veblen D.R. An AEM-TEM study of weathering and diagenesis, Abert Lake, Oregon: I. Weathering reactions in the volcanics. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 1991. Vol. 55. Iss. 10, p. 2781-2793. DOI: 10.1016/0016-7037(91)90444-A

- Kuznetsov V.A., Generalova V.A. Radionuclides mid titanium colloidal compounds in landscapes. Litasfera. 1999. N 10-11, p. 118-125 (in Russian).

- Cornell R.M., Schwertmann U. The Iron Oxides: Structure, Properties, Reactions, Occurrences and Uses. Wiley-VCH, 2003, p. 703.

- Hanlie Hong, Kaipeng Ji, Chen Liu et al. Authigenic anatase nanoparticles as a proxy for sedimentary environment and porewater pH. American Mineralogist. 2022. Vol. 107. Iss. 12, p. 2176-2187. DOI: 10.2138/am-2022-8330

- Menzies M., Seyfried Jr. W.E. Basalt-seawater interaction: trace element and strontium isotopic variations in experimentally altered glassy basalt. Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 1979. Vol. 44. Iss. 3, p. 463-472. DOI: 10.1016/0012-821X(79)90084-0

- Smith S.J., Stevens R., Shengfeng Liu et al. Heat capacities and thermodynamic functions of TiO2 anatase and rutile: Analysis of phase stability. American Mineralogist. 2009. Vol. 94. Iss. 2-3, p. 236-243. DOI: 10.2138/am.2009.3050

- Hishita S., Mutoh I., Koumoto K., Yanagida H. Inhibition mechanism of the anatase-rutile phase transformation by rare earth oxides. Ceramics International. 1983. Vol. 9. Iss. 2, p. 61-67. DOI: 10.1016/0272-8842(83)90025-1

- Liping Wang, Essene E.J., Youxue Zhang. Mineral inclusions in pyrope crystals from Garnet Ridge, Arizona, USA: implications for processes in the upper mantle. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology. 1999. Vol. 135. Iss. 2-3, p. 164-178. DOI: 10.1007/s004100050504

- Wülser P.-A., Brugger J., Meisser N. The crichtonite group of minerals: a review of the classification. Bull. Liaison S.F.M.C. 2004. Vol. 16, p. 76-77.

- Dekov V., Scholten J., Garbe-Schönberg C.-D. et al. Hydrothermal sediment alteration at a seafloor vent field: Grimsey Graben, Tjörnes Fracture Zone, north of Iceland. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth. 2008. Vol. 113. Iss. B11. N B11101. DOI: 10.1029/2007JB005526

- Ayupova N.R., Maslennikov V.V, Melekestseva I.Yu. et al. The Fate of “Immobile” Ti in Hyaloclastites: An Evidence from Silica–Iron-Rich Sedimentary Rocks of the Urals Paleozoic Massive Sulfide Deposits. Minerals. 2024. Vol. 14. Iss. 9. N 939. DOI: 10.3390/min14090939