Environmental assessment of biochar application for remediation of oil-contaminated soils under various economic uses

- 1 — Ph.D. Leading Researcher Southern Federal University ▪ Orcid

- 2 — Ph.D., Dr.Sci. Head of Department Southern Federal University ▪ Orcid

Abstract

Remediation is an important area of oil-contaminated soil restoration in Russia, since oil refining industry is the major one for Russia and neighbouring countries, and the issues of environmentally effective and economically profitable remediation of oil contamination have not yet been solved. Soils under various economic uses have different surface areas and degrees of soil particles envelopment with oil due to the presence or absence of cultivation, the amount of precipitation and plant litter. The introduction of various substances for remediation into oil-contaminated soils of steppes (arable land), forests, and semi-deserts, considering their differences, gives different results. Biochar is coal obtained by pyrolysis at high temperatures and in the absence of oxygen. The uniqueness of this coal lies in the combination of biostimulating and adsorbing properties. The purpose of the study is to conduct an environmental assessment of biochar application for remediation of oil-contaminated soils under various economic uses. The article compares the environmental assessments of biochar application in oil-contaminated soils with different particle size fraction. The following indicators of soil bioactivity were determined: enzymes, indicators of initial growth and development intensity of radish, microbiological indicators. We found that the most informative bioindicator correlating with residual oil content is the total bacteria count, and the most sensitive ones are the roots length (ordinary chernozem and brown forest soil) and the shoots length (brown semi-desert soil). The use of biochar on arable land and in forest soil (ordinary chernozem and brown forest soil) is less environmentally efficient than in semi-desert soil (brown semi-desert soil). The study results can serve to develop measures and managerial and technical solutions for remediation of oil-contaminated soils under various economic uses.

Funding

The study was conducted with the financial support of the project of the Strategic Academic Leadership Program of the Southern Federal University (Priority 2030) N SP-12-23-01; the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation in the Soil Health laboratory of the Southern Federal University, agreement N 075-15-2022-1122; the project of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation and the support of the youth laboratory under the Interregional Scientific and Educational Centre of the South of Russia, N FENW-2024-0001.

Introduction

Oil is the most common raw material for fuel production in the world [1]. Despite modern protection systems for tankers and pipelines during oil transportation, the number of accidents has increased significantly over the past couple of years both abroad and in Russia. In addition, clean soils without an external source of contamination also contain hydrocarbons, which are mainly of autochthonous natural origin [2]. As a result of contamination with oil and oil products, the biological condition of soils deteriorates due to the disruption of environmental and agricultural functions [3]. There are two directions for reducing the level of soil contamination with oil and oil products: 1) contamination prevention; 2) elimination of the contamination consequences with minimal damage to the environment [4-6].

In the Perm Region, monitoring of various sources of environmental pollution with oil and oil products is conducted using unmanned aerial vehicles [7]. For soil cleaning, radical sanitation methods such as removal of the contaminated layer is unacceptable, since it leads to degradation of the topsoil and its alienation. Phytoremediation is one of poorly effective but very gentle methods of restoring the soil condition [8]. The effectiveness of phytoremediation is limited by the high concentration of oil (no more than 1.5 %), soil hydrophobicity, and the need to select plants for each contamination situation [9, 10]. High soil hydrophobicity causes a decrease in plant growth and development due to disruption of water exchange in the cells of both the photosynthetic apparatus and in the stems and root system [11, 12]. Therefore, it is recommended to combine phytoreme-diation with other types of remediation, such as the introduction of calcium oxide or carbonate encapsulation [13].

It is necessary to evaluate the modern methods of bioremediation of oil-contaminated soils without expensive removal of the upper fertile layer or the use of ineffective phytoremediants [14, 15]. Bioremediation methods involve the use of biostimulants and bioaugmenters, which reduce the oil content and return the soil to an environmental state close to that of before contamination. One of the substances often used for bioremediation of soil contaminated with oil and oil products, heavy metals is biochar [16, 17]. Biochar is mainly produced from agricultural waste (rice and wheat straw, corn and cotton stalks, other remains of grass vegetation), forest waste (wood of various tree species), livestock waste (pig, cow manure), and municipal wastewater sludge. The use of rice husk biochar together with bacterial preparations (BP) in oil-contaminated soil regulates the microbial community succession and increases the number of microorganisms associated with oil degradation at the genus level [18]. Rice husk biochar also contributes to an increase in the number of soil fungi [19]. The application of biochar with compost together with a decrease in the oil content increases the growth and development of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.), corn (Zea mays L.), white clover (Trifolium repens L.), alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.), and ryegrass (Lolium multiflorum Lam.) [20]. Biochar introduced together with mycorrhiza into contaminated soil had a beneficial effect on the growth and development of clover (Trifolium arvense L.) and mallow (Malva sylvestris L.) as well as contributed to oil degradation [21]. Biochar obtained from corn was selected as a carrier to immobilize oil-degrading microorganisms: the best particle size fraction was 0.08 mm, and the best immobilization time was 18 h [22]. The application of biochar and rhamnolipid into oil-contaminated swampy soil in Louisiana wetlands (USA) allowed to increase the algae biomass, led to the growth of gram-positive bacteria, actinomycetes, arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and to a decrease in oil concentration [23]. Despite the advantages of biochar over other substances, its application in remediation of soil contaminated with oil and oil products is not always environmentally rational [24-26]. In remediation with biochar, the soil type and the substance concentration play an important role [27-29]. The application of biochar can both promote remediation and have a toxic effect on soil biota and cause soil alienation [30-32].

The objective is to conduct an environmental assessment of biochar application for remediation of oil-contaminated soils under various economic uses. The following tasks were set: to assess the residual oil content in soils under various economic uses (arable land, forest, and semi-desert) after introducing biochar; to analyse the change in bioindicators of soil condition; to assess the environmental efficiency of biochar in soils after oil contamination.

Methods

To study the biochar efficiency in remediation of oil-contaminated soils under various economic uses (arable land, forest, and semi-desert), the following were considered: ordinary chernozem (Haplic Chernozem Loamic), brown forest (Haplic Cambisols), and brown semi-desert soils (Endosalic Calcisols Yermic) [33] (Table 1). The choice of soil types was due to the fact that in the Rostov Region (ordinary chernozem), in the beech-hornbeam forest of the Republic of Adygeya (brown forest soil), and in the steppes of the Republic of Kalmykiya (brown semi-desert soil) oil and oil products are extracted, processed, or transported [34, 35]. Soil types differ in the land type, vegetation types, particle size fraction, soil reaction (pH), cation exchange capacity (CEC), and organic matter content (Corg).

Air-dry soil of each type was sifted through a 2 mm sieve and moistened, and then oil was added to the vegetation vessel at a concentration of 5 % of the soil mass. After the soil was contaminated, biochar was added to it in three concentrations: recommended – 5 %; half the recommended – 2.5 %; twice the recommended – 10 % of the soil mass.

Table 1

Sampling locations and characteristics of uncontaminated soils

|

Soil type |

Coordinates |

Sampling location |

Land type |

рН |

Сorg, % |

CEC, mEq/100 g [36] |

Particle size fraction |

|

Ordinary chernozem |

47°14'17.54''N; 39°38'33.22''E |

Rostov Region, Rostov-on-Don, Botanical Garden of the Southern Federal University |

Arable land |

7.3 |

7.6 |

33.6 |

Heavy loam |

|

Brown forest |

44°10'39.76"N; 40° 9'27.47"E |

Republic of Adygeya, Maikop district, Nikel village |

Beech-hornbeam forest |

5.3 |

1.3 |

24.3 |

Heavy loam |

|

Brown semi-desert |

46°17'48.65"N; 46°41'40.06"E |

Republic of Kalmykiya, Narimanovskii district, Drofinyi village |

Semi-desert |

6.7 |

1.0 |

6.5 |

Light loam |

After incubation of contaminated soils, the residual content of oil and oil products was analysed by infrared spectroscopy using carbon tetrachloride as an extractant (PND F 16.1: 2.2.22-98).

To assess the environmental efficiency of biochar application, the residual content of oil and bioindicators characterizing the environmental state of the soil were studied (Table 2).

Table 2

Methods for assessing the environmental state of oil-contaminated soils after remediation

|

Bioindicator |

Measurement method |

Source |

|

Catalase activity (Н2О2: Н2О2 – oxidoreductase, EC 1.11.1.6) |

Volumetric, assessing the volume of water displaced by oxygen as a result of hydrogen peroxide decomposition upon contact with soil, ml O2/1 g of soil in 1 min |

[37] |

|

Dehydrogenase activity (substrate: NAD(P) – oxidoreductase, EC 1.1.1) |

Reduction of triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) to triphenylformazans (TPF) under anaerobic conditions with spectrophotometric termination, mg TPF/10 g of soil in 24 h |

[38] |

|

Total bacteria count |

Fluorescence microscopy using acridine orange dye at ×40 magnification. Bacterial count, billion bacteria/1 g of soil |

[39] |

|

Radish shoots length |

After 7 days from the start of the phytotoxic experiment, radish (Raphanus sativus L.) shoots length was measured, mm |

[40] |

|

Radish roots length |

After 7 days from the start of the phytotoxic experiment, radish (Raphanus sativus L.) roots length was measured, mm |

[40] |

|

Radish germination |

Evaluation of radish (Raphanus sativus L.) germination after 7 days of the experiment, % |

[40] |

Based on the results of bioindicator determination, the integral indicator of the biological state of soils (IIBS) was estimated [41]. For the IIBS of ordinary chernozem, the relative values of each indicator were estimated in comparison with uncontaminated soil (control – 100 %). Relative values of this indicator for other experimental variants:

where B1 is the relative score of the indicator; Bх is the actual value of the bioindicator; Bmax is the maximum value of the indicator in the control.

The next stage of estimating the IIBS is summing up the relative values of bioindicators and estimating the average scores:

where Bavg is the average assessment score of the indicators; N is the number of indicators.

Final stage of estimation:

where Bref is the control value averaged over all biological indicators.

Statistical processing of the results was performed in the Statistica 12.0 software. Mean values and variance were determined using variance analysis (Studentʼs t-test).

Discussion of results

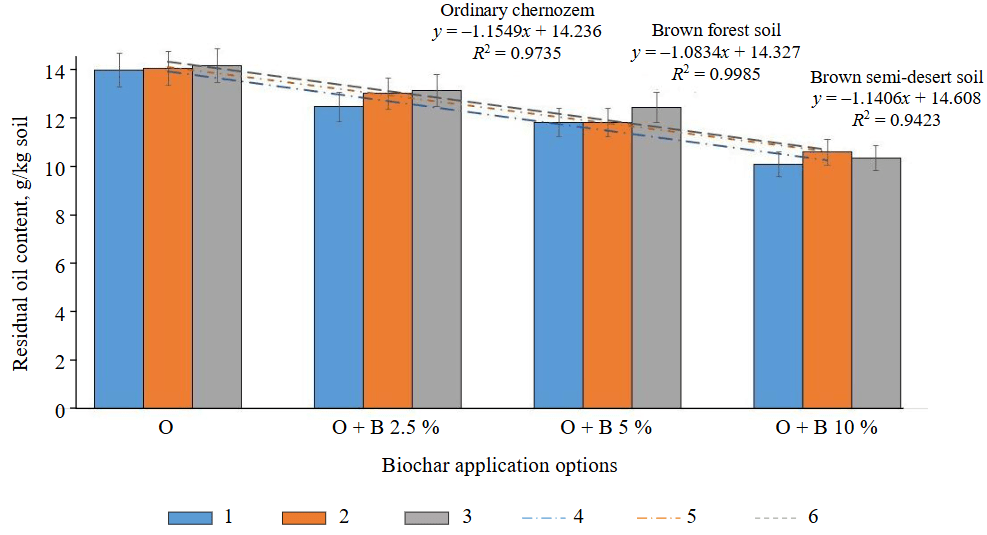

The residual oil content (Fig.1) after 30 days of the experiment and biochar application decreased by 10-27 % (ordinary chernozem), 7-24 % (brown forest), and 7-27 % (brown semi-desert). The higher the dose of biochar, the more effective the oil decomposition in the soil.

Fig.1. Residual oil content in soils after application of biochar at doses of 2.5; 5, and 10 % of the soil mass: O – soil after application of oil; B – biochar

1 – ordinary chernozem; 2 – brown forest soil; 3 – brown semi-desert soil; 4 – linear (ordinary chernozem); 5 – linear (brown forest soil); 6 – linear (brown semi-desert soil)

According to the regression equations and determination coefficients, the closest relationship between oil decomposition and the effect of biochar in different doses corresponds to brown forest soil (R2 = 0.9985), the least close to brown semi-desert (R2 = 0.9423), and ordinary chernozem corresponds to an intermediate value (R2 = 0.9735). The difference in oil decomposition in soils is associated with the particle size fraction, organic matter content, and reaction of the soil environment [32]. In heavy loamy soils, such as brown forest soil and ordinary chernozem, the biochar application reduces the oil content to a greater extent than in brown semi-desert soil, which has a sandy loam particle size fraction. Thus, the series of biochar efficiency for oil decomposition in soils is as follows: brown forest soil > ordinary chernozem > brown semi-desert soil.

The biological parameters of the studied soils after the biochar application are given in Table 3. After the introduction of oil into ordinary chernozem, the decrease in biological parameters relative to the control was from 34 % (catalase activity) to 99 % (radish shoots and roots length). During the remediation of oil-contaminated brown forest soil, the bioactivity varied from 12 % (dehydrogenase activity) to 74 and 87 % (shoots length and roots length, respectively) relative to the control. In brown semi-desert soil, oil inhibited bioactivity in the range from 11 % (dehydrogenase activity) to 44 % (shoots length). The difference in the bioindicator sensitivity is due to the soil structure: in heavy loamy soils, a significant decrease in the radish shoots and roots length was observed, while in light loamy soil, a decrease was found in the bacteria count and the radish shoots length.

When adding biochar at 2.5, 5 and 10 % of the ordinary chernozem mass, it was noted that with an increase in the biochar concentration, bioactivity increases: catalase activity by 5-19 %; dehydrogenase activity by 0.5-9 %; total bacteria count by 17-50 %; germination by 33-600 %; shoots length by 2-39 times; roots length by 2-54 times compared to the oil-contaminated background.

In brown forest soil, biochar, just like in chernozem, stimulated biological parameters with concentration increase: catalase activity by 8-20 %; dehydrogenase activity by 10-203 %; total bacteria count by 84-133 %; radish germination by 72-105 %; shoots length by 43-156 %; roots length by 73-274 % compared to oil-polluted background. In brown semi-desert soil, biochar stimulated catalase activity by 7-31 %; dehydrogenase activity by 3-8 %; total bacteria count by 11-18 %; germination by 15-28 %; shoots length by 20-31 %; roots length by 5-18 % compared to oil-polluted background.

Table 3

Change in biological parameters after adding biochar, abs. units

|

Variants |

Catalase activity, ml O2/1 g per 1 min |

Dehydrogenase activity, mg TPP/10 g per 24 h |

Radish (Raphanus sativus L.) germination, % |

Radish (Raphanus sativus L.) shoots length, mm |

Radish (Raphanus sativus L.) roots length, mm |

Total bacteria count, billion/1 g of soil |

|

|

Ordinary chernozem |

|||||||

|

Control |

7.4 |

29.9 |

84 |

24.7 |

50.7 |

1.60 |

|

|

O |

4.9 |

18.6 |

6 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

0.60 |

|

|

O + B 2.5 % |

5.1 |

18.7 |

8 |

0.5 |

0.9 |

0.70 |

|

|

O + B 5 % |

5.6 |

20.1 |

12 |

1.5 |

1.4 |

0.75 |

|

|

O + B 10 % |

5.8 |

20.3 |

42 |

8.2 |

16.6 |

0.90 |

|

|

Brown forest soil |

|||||||

|

Control |

6.4 |

9.8 |

90 |

27.1 |

44.2 |

1.20 |

|

|

O |

3.8 |

8.7 |

36 |

7.0 |

5.8 |

0.48 |

|

|

O + B 2.5 % |

4.1 |

9.6 |

62 |

10.1 |

10.2 |

0.89 |

|

|

O + B 5 % |

4.3 |

10.7 |

70 |

13.1 |

13.8 |

1.08 |

|

|

O + B 10 % |

4.6 |

26.5 |

74 |

18.1 |

21.9 |

1.13 |

|

|

Brown semi-desert soil |

|||||||

|

Control |

2.1 |

18.9 |

86 |

25.0 |

27.4 |

1.00 |

|

|

O |

1.3 |

16.9 |

66 |

14.0 |

24.2 |

0.62 |

|

|

O + B 2.5 % |

1.4 |

17.4 |

76 |

16.8 |

25.4 |

0.69 |

|

|

O + B 5 % |

1.52 |

17.8 |

78 |

18.3 |

26.9 |

0.70 |

|

|

O + B 10 % |

1.77 |

18.3 |

85 |

18.4 |

28.5 |

0.73 |

|

During remediation of ordinary chernozem and brown forest soil, a decrease in soil phytotoxicity was observed due to an increase in the length of radish shoots and roots by 15-399 and 27-543 times, respectively, compared to the oil-contaminated background. This effect is probably due to the porous structure of biochar, which allows partial adsorption of oil and stimulation of its decomposition, as well as improvement of the soil structure, which is important for the growth and development of the root system of plants [17, 31]. However, stimulation of phytotoxic indicators relative to oil-contaminated soils did not allow achieving the control level, which is an indicator of the state of soils with a heavy loamy composition under oil contamination. In brown semi-desert soil, control values were achieved already at a biochar dose of 5 % for germination and roots length of radish.

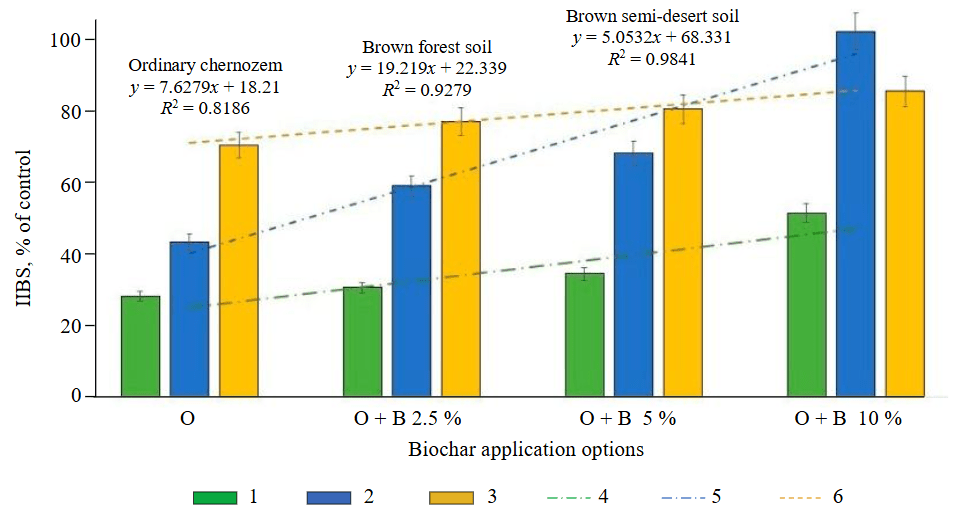

Fig.2. Change in the integral indicator of the biological state of soils after the biochar application in different doses

1 – ordinary chernozem; 2 – brown forest soil; 3 – brown semi-desert soil; 4 – linear (ordinary chernozem); 5 – linear (brown forest soil); 6 – linear (brown semi-desert soil)

According to Table 3, the integral indicator of the biological state was determined for each soil type after biochar application (Fig.2). According to estimations, in the soil without remediants, the IIBS of ordinary chernozem, brown forest, and brown semi-desert soils is 70, 55 and 27 % relative to the control. With the application of 2.5, 5, and 10 % biochar, the IIBS of ordinary chernozem changed by 46-68 % relative to the control. After applying biochar, the IIBS value of chernozem close to the control was not observed. The IIBS of brown forest soil increased at biochar doses of 2.5 and 5 % by 16 and 25 % relative to the oil-contaminated background (39 and 29 % lower than the control, respectively). At a biochar dose of 10 %, the IIBS of brown forest soil reached the control. In brown semi-desert soil, the IIBS value increased proportionally to the increase in the biochar dose of 2.5, 5, and 10 % by 20, 16, and 11 % below the control, respectively.

According to the regression equations presented in Fig.2, it is obvious that the change in the IIBS of each soil after remediation correlated differently with the oil content: from the highest correlation degree for brown semi-desert soil (R2 = –0.98) to the lowest one among the three soils for ordinary chernozem (R2 = –0.82). According to the efficiency of biochar application taken from the IIBS value, a series of soils was compiled: brown semi-desert soil > brown forest soil > ordinary chernozem.

The information content of each indicator and each soil type was assessed based on the strength of the correlation between the residual oil content and the value of all bioindicators (Table 4).

All bioindicators in the remediation of ordinary chernozem are informative (r > 0.90), but the most informative is the total bacteria count (r = –1.00). In the remediation of brown forest soil, the most informative indicator is the catalase activity (r = –1.00), and the least informative is the dehydrogenases activity (r = 0.04). For brown semi-desert soil, the most informative bioindicator is the total bacteria count (r = –0.99), and the least informative is the radish roots length (r = –0.51).

Coefficient r of correlation between the bioindicator value and the residual oil content

|

Catalase activity |

Dehydrogenase activity |

Radish germination |

Radish shoots length |

Radish roots length |

Total bacteria count |

|

Ordinary chernozem |

|||||

|

–0.98** |

–0.99** |

–0.97** |

–0.99** |

–0.99** |

–1.00** |

|

Brown forest soil |

|||||

|

–1.00** |

0.04 |

–0.80* |

–0.95** |

–0.98** |

–0.64* |

|

Brown semi-desert soil |

|||||

|

–0.96** |

–0.88** |

–0.72* |

–0.96** |

–0.51 |

–0.99** |

Notes:

Significance of difference from control: * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.001.

For remediation of oil-contaminated ordinary chernozem and brown semi-desert soil with biochar, the most informative indicator is the total bacteria count, and for brown forest soil, the most informative indicator is catalase activity. Differences in the informativeness of the indicators for each soil type are due not only to their structure, but also to the content of organic matter and the soil environment reaction [42]. Among the studied samples, only in brown forest soil the soil environment reaction is acid (pH = 5.7), while in brown semi-desert soil (pH = 6.7) and ordinary chernozem (pH = 7.3) it is alkaline (see Table 1). The soil bacteria count is an informative bioindicator of oil-contaminated soil remediation [43].

The sensitivity of bioindicators was assessed by the difference with the control: the higher the value is than the control, the more sensitive the soil is to remediation (Table 5). The greater the difference from oil-contaminated soil without remediants, the more sensitive the indicator. Thus, for remediation of ordinary chernozem and brown forest soil with biochar, the most sensitive bioindicator is the roots length, and the least sensitive is the dehydrogenases and catalase activity.

Table 5

Relative values of bioindicators for each soil type (averaged by biochar doses), % of oil-contaminated soil without remediants

|

Catalase activity |

Dehydrogenase activity |

Radish germination |

Radish shoots length |

Radish roots length |

Total bacteria count |

|

Ordinary chernozem |

|||||

|

113 |

106 |

344 |

1,697 |

2,104 |

131 |

|

Brown forest soil |

|||||

|

113 |

179 |

191 |

195 |

261 |

214 |

|

Brown semi-desert soil |

|||||

|

117 |

106 |

121 |

127 |

111 |

114 |

For remediation of brown semi-desert soil, the most sensitive bioindicator is shoots length, and the least sensitive is dehydrogenase activity. Brown semi-desert soil of the Chernozemel’skii district of the Republic of Kalmykiya, when contaminated with fuel oil and kerosene at a rate of 2.5 % of the soil mass, stimulated the growth of radish shoots and roots [44]. It was also previously determined that the combined treatment with biochar and rhamnolipid has the lowest ecotoxicity for plants and algae when used for remediation of oil-polluted wetlands [23].

The most sensitive indicator in the remediation of oil-contaminated ordinary chernozem (arable land, steppe soil) and brown forest soil (forest soil) with biochar is the radish roots length, and in brown semi-desert soil (semi-desert) – the radish shoots length.

The study results are important since thousands of hectares of soil are contaminated with oil and oil products every year due to various economic uses. The application of a single concentration of biochar for all types of soil is environmentally ineffective. The use of biochar for cleaning oil-contaminated soil depends on the soil type, the natural material from which the biochar is made, and the contamination level [45]. When remediating oil-contaminated soils with biochar, in addition to oil concentration, it is necessary to consider the agroclimatic (air temperature, amount of precipitation, wind speed), agrochemical (N content), and physicochemical parameters of the soil (humus, pH, particle size fraction, BOD, COD, easily soluble salt content). Biochar, due to the adsorbent properties, can be used in any climatic zone, since the adsorption rate does not depend on the temperature and moisture content of the soil [46-48]. Biochar as a biostimulant is more effective in soils formed in climatic conditions with a sufficient number of sunny days and precipitation, such as in soils of the steppe and forest zones.

The use of biochar is inextricably linked with the soil type (ordinary chernozem, brown forest, chestnut, brown semi-desert, solonchak, etc.) and the type of agricultural use (steppe, forest, and semi-desert). In the steppe zone of Russia (for example, in the Rostov Region and Krasnodar Territory), arable and virgin soils predominate, represented by various chernozems and chestnut soil subtypes, with a heavy loamy particle size fraction, high and medium humus and nitrogen content in the soil, and high soil buffering. As a result, in case of oil contamination of such soils, biochar application is effective, and the efficiency increases in combination with microbial preparations and humic substances [49-53]. The degradation of petroleum hydrocarbons in forest soils is influenced by the carbon and nitrogen ratio, which promotes the development of native microbiota, including oil-degrading bacteria [54-56]. The use of biochar for the remediation of forests and forest-steppes, as in the Republic of Adygeya, allows stimulating native microbiota due to the carbon introduced into the soil. The application of biochar in semi-desert soils, for example, in the Republic of Kalmykiya and the Astrakhan Region, is less effective, since it is directly related to the light particle size fraction of the soils, the virtual absence of vegetation in the soil cover, and the low content of humus and nitrogen. Therefore, the most sensitive bioindicator in the remediation of brown semi-desert soil is not the roots length, as in steppe and forest soils, but the radish shoots length. The greater sensitivity of shoots length is associated with the greater number of sunny days in the region. Thus, the application of biochar for oil contamination remediation and environmental restoration of the soil helps to reduce the pollutant concentration and is of great importance for the sustainable development of plants.

The informativeness of the bioindicator in case of contamination by oil and oil products is important first of all, since the connection between the amount of decomposed oil and the response of the bioindicator is considered [53, 57, 58]. The activity of microorganisms (fungi and bacteria) is one of the most informative, but not the most sensitive indicators [59]. The bioindicator sensitivity is determined by the indicator stimulation relative to the control. In case of oil contamination, the sensitivity is judged by the ratio of the bioindicator and the oil-polluted background, as well as the control. The use of microbiological preparations containing bacteria, fungi, and algae, i.e. microbial consortia, is most effective [60]. In case of oil contamination of sod-podzolic, light-gray, sod-carbonate, dark-gray, and floodplain soils, phytotesting methods (garden cress (Lepidium sativum L.), soft wheat (Triticum aestivum L.), Siberian spruce (Picea obovata Ledeb.), and Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) observed the greatest resistance to oil contamination in floodplain soil, and the greatest vulnerability in sod-carbonate and light-gray soils [61]. In some cases, despite the set of measures such as collection and removal of spilled oil, the use of specialized oil extraction units, the application of nitrogen fertilizers, loosening and phytoremediation, the oil content in peat-gley soil is not reduced sufficiently and is dangerous for the surrounding ecosystem [62]. The application of biochar inoculated with Bacillus and Paenibacillus microorganisms is also effective with preliminary BP inoculation in biochar – stimulation of dehydrogenase activity by 27 % of the background value. The most informative bioindicators of the soil are obtained when biochar is applied with Bacillus and Paenibacillus. Their application stimulates catalase activity, the total bacteria count in oil-contaminated chernozem, and increases the barley roots length, showing the greatest sensitivity [63].

Conclusion

The application of biochar for remediation of oil contaminated soils under various economic uses has different environmental efficiency. The oil content after biochar application decreases in all soils, regardless of the type of economic use. The most sensitive bioindicators for biochar remediation of arable land and forest soil are the roots length, and for semi-deserts, the shoots length. The most informative indicators for biochar remediation of oil-contaminated ordinary chernozem and brown semi-desert soil are the total bacteria count, and for brown forest soil, the catalase activity. From the point of view of environmental efficiency assessed by the integral indicator of the biological state of soils, the application of biochar on arable land and in forest soil (ordinary chernozem and brown forest soil) is less environmentally efficient than in semi-deserts (brown semi-desert soil). The obtained results serve to develop measures and managerial and technical solutions for the remediation of oil-contaminated soils under various economic uses.

References

- Vasileva G.K., Strizhakova E.R., Bocharnikova E.A. et al. Oil and oil products as soil pollutants. Technology of combined physical and biological decontamination of soils. Rossiiskii khimicheskii zhurnal. 2013. Vol. 57. N 1, p. 79-104.

- Pikovskii Yu.I., Smirnova M.A., Gennadiev A.N. et al. Parameters of the Native Hydrocarbon Status of Soils in Different Bioclimatic Zones. Eurasian Soil Science. 2019. Vol. 52. N 11, p. 1333-1346. DOI: 10.1134/S1064229319110085

- Vodyanitskii Yu.N., Shoba S.A. Biogeochemical barriers for soil and groundwater bioremediation. Lomonosov Soil Science Journal. 2016. N 3, p. 3-15 (in Russian).

- Bykova M.V., Pashkevich M.A. Assessment of oil pollution of soils of production facilities of different soil and climatic zones of the Russian Federation. News of the Tula state university. Sciences of Earth. 2020. N 1, p. 46-59 (in Russian). DOI: 10.46689/2218-5194-2020-1-1-46-59

- Polyakov R.Yu., Khotnikov E.L., Mozgovoi N.V., Bokadarov S.A. Modern means and technologies for eliminating the consequences of soil contamination by oil and oil products. Pozharnaya bezopasnost: problemy i perspektivy. 2013. N 1 (4), p. 343-345.

- Shuguang Wang, Yan Xu, Zhaofeng Lin et al. The harm of petroleum-polluted soil and its remediation research. AIP Conference Proceedings. 2017. Vol. 1864. Iss. 1. N 020222. DOI: 10.1063/1.4993039

- Buzmakov S.A., Sannikov P.Yu., Kuchin L.S. et al. The use of unmanned aerial photography for interpreting the technogenic transformation of the natural environment during the oilfield operation. Journal of Mining Institute. 2023. Vol. 260, p. 180-193. DOI: 10.31897/PMI.2023.22

- Ahmad A.A., Muhammad I., Shah T. et al. Remediation Methods of Crude Oil Contaminated Soil. World Journal of Agriculture and Soil Science. 2020. Vol. 4. Iss. 4. N WJASS.MS.ID.000595. DOI: 10.33552/WJASS.2020.04.000595

- Okoye P.C., Ikhajiagbe B., Obayuwana H.O., Ehiarinmwian R.I. Plant-assisted remediation of oil-polluted soil by five commonly cultivated local edible shrubs. Nigerian Journal of Scientific Research. 2018. Vol. 17 (1), p. 55-63.

- Telysheva G., Jashina L., Lebedeva G. et al. Use of Plants to Remediate Soil Polluted With Oil. Environment. Technology. Resources. Proceedings of the 8th International Scientific and Practical Conference, 20-22 June 2011, Rēzekne, Latvia. Rēzekne, 2011. Vol. 1, p. 38-45. DOI: 10.17770/ETR2011VOL1.925

- Vysotskaya L.B., Arkhipova T.N., Kuzina E.V. et al. Comparison of responses of different plant species to oil pollution. Biomics. 2019. Vol. 11. N 1, p. 86-100. DOI: 10.31301/2221-6197.bmcs.2019-06

- Tang K.H.D., Angela J. Phytoremediation of crude oil-contaminated soil with local plant species. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. 2019. Vol. 495. N 012054. DOI: 10.1088/1757-899X/495/1/012054

- Pashayan A.A., Nesterov A.V., Shchetinskaya O.S., Melnikova E.A. Recultivation of Oil-Contaminated Soils by Reagent Encapsulation with their Subsequent Phytoremediation. Ecology and Industry of Russia. 2022. Vol. 26. N 9, p. 20-25 (in Russian). DOI: 10.18412/1816-0395-2022-9-20-25

- Slusarevsky A.V., Zinnatshina L.V., Vasilyeva G.K. Comparative Environmental and Economic Analysis of Methods for the Remediation of Oil-Contaminated Soils by in situ Bioremediation and Mechanical Soil Replacement. Ecology and Industry of Russia. 2018. Vol. 22. N 11, p. 40-45 (in Russian). DOI: 10.18412/1816-0395-2018-11-40-45

- Kuzina E.V., Rafikova G.F., Stolyarova E.A., Loginov O.N. Efficiency of Associations of Legume Plants and Growth-Stimulating Bacteria for Restoration of Oil-Contaminated Soils. Agrohimia. 2021. N 4, p. 87-96 (in Russian). DOI: 10.31857/S0002188121040074

- Anae J., Ahmad N., Kumar V. et al. Recent advances in biochar engineering for soil contaminated with complex chemical mixtures: Remediation strategies and future perspectives. Science of the Total Environment. 2021. Vol. 767. N 144351. DOI: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.144351

- Zahed M.A., Salehi S., Madadi R., Hejabi F. Biochar as a sustainable product for remediation of petroleum contaminated soil. Current Research in Green and Sustainable Chemistry. 2021. Vol. 4. N 100055. DOI: 10.1016/j.crgsc.2021.100055

- Yuanfei Lv, Jianfeng Bao, Dongyang Liu et al. Synergistic effects of rice husk biochar and aerobic composting for heavy oil-contaminated soil remediation and microbial community succession evaluation. Journal of Hazardous Materials. 2023. Vol. 448. N 130929. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2023.130929

- Chuan Yin, Huan Yan, Yuancheng Cao, Huanfang Gao. Enhanced bioremediation performance of diesel-contaminated soil by immobilized composite fungi on rice husk biochar. Environmental Research. 2023. Vol. 226. N 115663. DOI: 10.1016/j.envres.2023.115663

- Yousaf U., Khan A.H.A., Farooqi A. et al. Interactive effect of biochar and compost with Poaceae and Fabaceae plants on remediation of total petroleum hydrocarbons in crude oil contaminated soil. Chemosphere. 2022. Vol. 286. Part 2. N 131782. DOI: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.131782

- Abbaspour A., Zohrabi F., Dorostkar V. et al. Remediation of an oil-contaminated soil by two native plants treated with biochar and mycorrhizae. Journal of Environmental Management. 2020. Vol. 254. N 109755. DOI: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.109755

- Hongyang Ren, Yuanpeng Deng, Liang Ma et al. Enhanced biodegradation of oil-contaminated soil oil in shale gas exploitation by biochar immobilization. Biodegradation. 2022. Vol. 33. Iss. 6, p. 621-639. DOI: 10.1007/s10532-022-09999-6

- Zhuo Wei, Jim J. Wang, Yili Meng et al. Potential use of biochar and rhamnolipid biosurfactant for remediation of crude oil-contaminated coastal wetland soil: Ecotoxicity assessment. Chemosphere. 2020. Vol. 253. N 126617. DOI: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.126617

- Smirnova E.V., Okunev R.V., Giniyatullin K.G. Influence of carbon sorbents on the potential ability of soils to self-cleaning from petroleum pollution. Georesources. 2022. Vol. 24. N 3, p. 210-218 (in Russian). DOI: 10.18599/grs.2022.3.18

- Dike C.C., Shahsavari E., Surapaneni A. et al. Can biochar be an effective and reliable biostimulating agent for the remediation of hydrocarbon-contaminated soils? Environment International. 2021. Vol. 154. N 106553. DOI: 10.1016/j.envint.2021.106553

- Dike C.C., Hakeem I.G., Rani A. et al. The co-application of biochar with bioremediation for the removal of petroleum hydrocarbons from contaminated soil. Science of the Total Environment. 2022. Vol. 849. N 157753. DOI: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.157753

- Gorovtsov A.V., Minkina T.M., Mandzhieva S.S. et al. The mechanisms of biochar interactions with microorganisms in soil. Environmental Geochemistry and Health. 2020. Vol. 42. Iss. 8, p. 2495-2518. DOI: 10.1007/s10653-019-00412-5

- Hongyang Lin, Yang Yang, Zhenxiao Shang et al. Study on the Enhanced Remediation of Petroleum-Contaminated Soil by Biochar/g-C3N4 Composites. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022. Vol. 19. Iss. 14. N 8290. DOI: 10.3390/ijerph19148290

- Minnikova T., Ruseva A., Kolesnikov S. Assessment of Ecological State of Soils Contaminated by Petroleum Hydrocarbons after Bioremediation. Environmental Processes. 2022. Vol. 9. Iss. 3. N 49. DOI: 10.1007/s40710-022-00604-9

- Haider F.U., Xiukang Wang, Zulfiqar U. et al. Biochar application for remediation of organic toxic pollutants in contaminated soils; An update. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety. 2022. Vol. 248. N 114322. DOI: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2022.114322

- Murtaza G., Ahmed Z., Eldin S.M. et al. Biochar as a Green Sorbent for Remediation of Polluted Soils and Associated Toxicity Risks: A Critical Review. Separations. 2023. Vol. 10. Iss. 3. N 197. DOI: 10.3390/separations10030197

- Xin Sui, Xuemei Wang, Yuhuan Li, Hongbing Ji. Remediation of Petroleum-Contaminated Soils with Microbial and Microbial Combined Methods: Advances, Mechanisms, and Challenges. Sustainability. 2021. Vol. 13. Iss. 16. N 9267. DOI: 10.3390/su13169267

- World Reference Base for Soil Resources. International soil classification system for naming soils and creating legends for soil maps. Vienna: International Union of Soil Sciences, 2022. 236 p. URL: https://www.isric.org/sites/default/files/WRB_fourth_edition_2022-12-18.pdf

- Daud R.M., Kolesnikov S.I., Minnikova T.V. et al. Biodiagnostics of arid soils resistance in the South of Russia to conta-mination by heavy metals, petroleum hydrocarbons, and biocides. Rostov-on-Don: Izd-vo Yuzhnogo federalnogo universiteta, 2021, p. 217.

- Sangadzhieva L.Ch., Davaeva Ts.D., Buluktaev A.A. Influence of oil pollution on phytotoxicity of light brown soils of Kalmykia. Bulletin of Kalmyk university. 2013. N 1 (17), p. 44-47 (in Russian).

- Valkov V.F., Kazeev K.Sh., Kolesnikov S.I. Soils of the South of Russia. Rostov-na-Donu: Everest, 2008, p. 276.

- Baikhamurova M.O., Yuldashbek D.H., Sainova G.A., Anarbekova G.D. Change of catalase and urease activity at high content of heavy metals (Pb, Zn, Cd) in serozem. European Journal of Natural History. 2020. N 3, p. 70-73.

- Małachowska-Jutsz A., Matyja K. Discussion on methods of soil dehydrogenase determination. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology. 2019. Vol. 16. Iss. 12, p. 7777-7790. DOI: 10.1007/s13762-019-02375-7

- Polyanskaya L.M., Pinchuk I.P., Stepanov A.L. Comparative Analysis of the Luminescence Microscopy and Cascade Filtration Methods for Estimating Bacterial Abundance and Biomass in the Soil: Role of Soil Suspension Dilution. Eurasian Soil Science. 2017. Vol. 50. N 10, p. 1173-1176. DOI: 10.1134/S1064229317100088

- Quintela-Sabarís C., Marchand L., Kidd P.S. et al. Assessing phytotoxicity of trace element-contaminated soils phytomanaged with gentle remediation options at ten European field trials. Science of the Total Environment. 2017. Vol. 599-600, p. 1388-1398. DOI: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.04.187

- Kolesnikov S.I., Kazeev K.S., Akimenko Y.V. Development of regional standards for pollutants in the soil using biological parameters. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment. 2019. Vol. 191. Iss. 9. N 544. DOI: 10.1007/s10661-019-7718-3

- Tunç E., Şahin E.Z., Demir M. et al. Investigation of Factors Affecting Catalase Enzyme Activity In Different Agricultural Soils. 1st International Congress on Sustainable Agriculture and Technology, 1-3 April 2019, Gaziantep, Turkey. Gaziantep University, 2019, p. 103-116.

- Bakaeva M.D., Kuzina E.V., Rafikova G.F. et al. Application of auxin producing bacteria in phytoremediation of oil-contaminated soil. Theoretical and Applied Ecology. 2020. N 1, p. 144-150 (in Russian). DOI: 10.25750/1995-4301-2020-1-144-150

- Buluktaev A.A. Phytotoxicity of oil-polluted soils in arid territories: analyzing results of simulation experiments. Russian Journal of Ecosystem Ecology. 2019. Vol. 4 (3), p. 10 (in Russian). DOI: 10.21685/2500-0578-2019-3-5

- Xue Yang, Shiqiu Zhang, Meiting Ju, Le Liu. Preparation and Modification of Biochar Materials and their Application in Soil Remediation. Applied Sciences. 2019. Vol. 9. Iss. 7. N 1365. DOI: 10.3390/app9071365

- Masiello C.A., Dugan B., Brewer C.E. et al. Biochar effects on soil hydrology. Biochar for Environmental Management. Science, Technology and Implementation. Routledge. 2015, p. 543-562. DOI: 10.4324/9780203762264

- Kinney T.J., Masiello C.A., Dugan B. et al. Hydrologic properties of biochars produced at different temperatures. Biomass and Bioenergy. 2012. Vol. 41, p. 34-43. DOI: 10.1016/j.biombioe.2012.01.033

- Van Gestel M., Ladd J.N., Amato M. Microbial biomass responses to seasonal change and imposed drying regimes at increasing depths of undisturbed topsoil profiles. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 1992. Vol. 24. Iss. 2, p. 103-111. DOI: 10.1016/0038-0717(92)90265-Y

- Muratova A.Yu., Panchenko L.V., Dubrovskaya E.V. et al. Bioremediation Potential of Biochar-Immobilized Cells of Azospirillum brasilense. Microbiology. 2022. Vol. 91. N 5, p. 514-522. DOI: 10.1134/S0026261722601336

- Minnikova T.V., Kolesnikov S.I., Minin N.S. Evaluation of dehydrogenases and invertase activity in petroleum-hydrocarbon-contaminated haplic chernozem during remediation with biochar and bacterial preparation. Biosphere. 2024. Vol. 16. N 1, p. 36-44 (in Russian). DOI: 10.24855/biosfera.v16i1.891

- Minnikova T., Kolesnikov S., Minkina T., Mandzhieva S. Assessment of Ecological Condition of Haplic Chernozem Calcic Contaminated with Petroleum Hydrocarbons during Application of Bioremediation Agents of Various Natures. Land. 2021. Vol. 10. Iss. 2. N 169. DOI: 10.3390/land10020169

- Minnikova T., Kolesnikov S., Minin N. et al. The Influence of Remediation with Bacillus and Paenibacillus Strains and Biochar on the Biological Activity of Petroleum-Hydrocarbon-Contaminated Haplic Chernozem. Agriculture. 2023. Vol. 13. Iss. 3. N 719. DOI: 10.3390/agriculture13030719

- Ruseva A., Minnikova T., Kolesnikov S. et al. Assessment of the ecological state of haplic chernozem contaminated by oil, fuel oil and gasoline after remediation. Petroleum Research. 2024. Vol. 9. Iss. 1, p. 155-164. DOI: 10.1016/j.ptlrs.2023.03.002

- Kudeyarov V.N. The agrobiogeochemical cycles of carbon and nitrogen of Russian croplands. Agrohimia. 2019. N 12, p. 3-15 (in Russian). DOI: 10.1134/S000218811912007X

- Uligova T.S., Tsepkova N.L., Rapoport I.B. et al. Forest Biogeocoenoses in the Area of Brown Forest Soils of the Western Caucasus. Biology Bulletin. 2023. Vol. 50. N 1, p. 70-84. DOI: 10.1134/S1062359023010132

- Ryzhova I.M., Podvezennaya M.A., Kirillova N.P. Analysis of the effect of moisture content on the spatial variability of carbon stock in forest soil of European Russia using databases. Lomonosov Soil Science Journal. 2022. N 2, p. 20-27 (in Russian).

- Lukoshkova A.A., Popova L.F. Microbiological activity of soils contaminated with oil products. Nauchnye mezhdistsiplinarnye issledovaniya. Sbornik statei VI Mezhdunarodnoi nauchno-prakticheskoi konferentsii, 25 oktyabrya 2020, Saratov, Russia. Saratov: Nauchno-obrazovatelnaya organizatsiya “Tsifrovaya nauka”, 2020, p. 11-15 (in Russian). DOI: 10.24412/cl-36007-2020-6-11-15

- Morachevskaya E.V., Voronina L.P. Bioassay as a method of integral assessment for remediation of oil-contaminated ecosystems. Theoretical and Applied Ecology. 2022. N 1, p. 34-43. DOI: 10.25750/1995-4301-2022-1-034-043

- Usacheva Yu.N. Methods of bioindication in assessment of oil-contaminated soils under recultivation work. Ecology and Industry of Russia. 2012. N 11, p. 40-43 (in Russian). DOI: 10.18412/1816-0395-2012-11-40-43

- Sozina I.D., Danilov A.S. Microbiological remediation of oil-contaminated soils. Journal of Mining Institute. 2023. Vol. 260, p. 297-312. DOI: 10.31897/PMI.2023.8

- Buzmakov S.A., Andreev D.N., Nazarov A.V. et al. Responses of Different Test Objects to Experimental Soil Contamination with Crude Oil. Russian Journal of Ecology. 2021. Vol. 52. N 4, p. 267-274. DOI: 10.1134/S1067413621040056

- Maslov M.N., Maslova O.A., Ezhelev Z.S. Microbiological Transformation of Organic Matter in Oil-Polluted Tundra Soils after Their Reclamation. Eurasian Soil Science. 2019. Vol. 52. N 1, p. 58-65. DOI: 10.1134/S1064229319010101

- Minnikova T., Kolesnikov S., Revina S. et al. Enzymatic Assessment of the State of Oil-Contaminated Soils in the South of Russia after Bioremediation. Toxics. 2023. Vol. 11. Iss. 4. N 355. DOI: 10.3390/toxics11040355