Geochemistry of spodumene from pegmatites of the Laghman granitoid complex, Afghanistan

- 1 — Ph.D., Dr.Sci. Professor Empress Catherine II Saint Petersburg Mining University ▪ Orcid ▪ Scopus

- 2 — Postgraduate Student Empress Catherine II Saint Petersburg Mining University ▪ Orcid

Abstract

The article presents the first data on the rare element contents in the compositions of spodumene from pegmatites of the Laghman granitoid complex in Eastern Afghanistan, the Kolatan, Digal, Gulsalak, and Tsamgal deposits. The analyses were performed by SIMS method. The paragenetic features of spodumene were determined. It is present in spodumene-microcline-albite, spodumene-albite, and spodumene-lepidolite-clevelandite pegmatites in amounts of 10-35 %. The crystals range in size from a few mm to 1.5-2 m, sometimes to 3 m long. The crystals are prismatic, board-shaped, and rectangular. The contents of minor and rare elements in spodumene vary significantly from the centre to the edge of the crystals. The increase in the contents of Li (36,571-51,040), Na (378-1542), Mn (103-2877), Ga (24.4-90.1), Sn (5.52-382), Ti (1.3-79.5), Zn (0.37-38.4) ppm is accompanied by a decrease in the concentrations of K (3.86-147), Ca (1.39-105), Mg (0.26-276), B (1.69-57.3), Cr (2.75-15.1), Cu (0.65-11.6), Cs (0.0-8.75), Be (0.03-9.54), Ta (0.03-2.09), Sr (0.03-3.09), V (0.07-3.11), Rb (0.02-1.56), Ba (0.03-3.17), Zr (0.01-1.6) ppm. The amount of Fe decreases from the centre to the edge, and Mn and Sn increase from the centre to the edge in all crystals. In the pinkish-violet zone of the crystal, Mn content is significantly higher than Cr and Fe. A positive correlation is observed between Li and Na, Mn, Fe, Ga, Sn, B, Cr, Ti, Be and a negative correlation with K, Cs, Ta, and Nb. Spodumene from the Dara-e-Pech deposit contains more gallium than from the Kolatan and Tsamgal deposits, which is of practical importance. Sharp boundaries between growth zones indicate a diffusion rate that was less than the rate of crystal growth that occurred in conditions of pegmatite melt crystallization. As a result of the exchange with the residual melt, insignificant post-crystallization diffusion and restoration of equilibrium between the crystal and the environment took place.

Introduction

Spodumene LiAlSi2O6 is the main lithium mineral, which is usually associated with quartz, albite, microcline, mica, beryl, and minor accessory minerals in granitic pegmatites. It typically contains 64.5 % SiO2, 27.4 % Al2O3, and 8.4 % Li2O in average composition [1, 2] and is used as a source of high-purity lithium. The demand for lithium in modern industry is increasing due to its special physical and chemical properties. 43-65 % of mined lithium is used in batteries for electric vehicles [3-5] participating in “green tech” [6-8], 28 % of lithium is used in the production of ceramics andф special glass [9-11], 7 % is used for high-temperature lubricants [12], polymers [4], foundry flux [5], aluminium alloys [13], and pharmaceuticals [3].

Spodumene has three main modifications – α, β, and γ. They differ from each other in their crystal structure and stability to external influences. The stable low-temperature variety is α-spodumene. It crystallizes in the monoclinic crystal system [14, 15]; β-spodumene has a tetragonal crystal lattice, is a product of recrystallization upon heating of α-spodumene to t = 900-1100 °C; γ-spodumene crystallizes in the hexagonal crystal system, is unstable under natural conditions. It is formed during transformation of α-spodumene into β-spodumene upon heating of α-spodumene to t = 700-900 °C [1, 16, 17]. In Afghan pegmatites, α-spodumene (ore-forming) is widespread. It includes gem-quality varieties of kunzite, hiddenite, and tryphane. Gem-quality spodumenes are found in the eastern part of the country, in the provinces of Nuristan, Laghman, Kunar, and Nangarhar.

The study area is considered one of the largest rare-metal metallogenic provinces in the world [18-20]. In 1977, L.N.Rossovsky and V.M.Chmyrev discovered twenty-four deposits of rare-metal pegmatites here [18]. Twenty-one were in the provinces of Nuristan, Kunar, Laghman, Nangarhar, and Badakhshan and three were in Central Afghanistan [20, 21].

The article presents the results of SIMS determination of minor and rare element contents in fourteen spodumene crystals from the Kolatan, Digal, Gulsalak, and Tsamgal deposits in Eastern Afghanistan. The aim of the study is to find patterns of changes in the composition of crystals in different growth zones depending on the crystallization conditions during pegmatite formation.

The colour of spodumene depends on the impurities of minor and rare elements [22, 23]. The study of these elements in spodumene enables to determine their distribution patterns in the mineral structure and to answer long-standing fundamental questions about the causes and features of crystal zoning in granite pegmatites in connection with the transition from the magmatic stage to the hydrothermal stage [24-26]. A change in the physical and chemical conditions of crystal growth can contribute to the formation of varieties of the studied mineral that differ in crystallographic parameters, the growth of microstructural deformation zones, as occurs at the contact between quartz of the hexagonal and trigonal crystal systems.

Detailed SIMS studies of the microelement composition of spodumene from Afghanistan were conducted for the first time. In most publications on the compositions of spodumene from different regions of the world, the mineral was studied using various methods [27-29], such as spectral or cathodoluminescence microscopy, SEM, EMPA, LA-ICP-MS, but none of the studies used a very accurate method – SIMS. Thus, this work represents the first results of determining rare elements in spodumenes from rare-metal pegmatites of the Laghman granitoid complex using the SIMS method. The obtained data are planned to be used to identify geochemical relationships between the compositions of the mineral and the host pegmatites.

The advantage of SIMS analysis is its high accuracy – one milligram per ton, unlike others, where the accuracy does not exceed one gram per ton. For spodumene, this is important when determining the content of microcomponents and lithium, as the main element in the crystal growth zones. Thanks to SIMS, information on the impurity composition and zoning of spodumene from deposits in Eastern Afghanistan was obtained for the first time.

Geological characteristics and field studies of pegmatites

The Nuristan tectonic zone is in Eastern Afghanistan. It is ore controlling for the country’s rare-metal pegmatites. It extends along the Hindu Kush – Pamir mountain ranges within the Nuristan mountain system. The tectonic zone is oriented in the near-N-S and N-E directions. It is 400 km long, and its maximum width in the southwest is 130 km. The tectonic zone passes through the outcrops of the ancient Precambrian basement [19, 20], and partially through a complex of the Paleozoic-Mesozoic deposits. The Precambrian basement complex is represented by gneisses, marbles, amphibolites, quartzites, crystalline schists, and amphibolite facies [30]. The dislocated sedimentary cover is composed of the Carboniferous-Permian marbleized limestones, quartzites, and mica schists [31]. The Triassic strata are represented by quartz-mica, garnet-staurolite, and dark grey phyllitic schists with a small amount of limestones and quartzites [21].

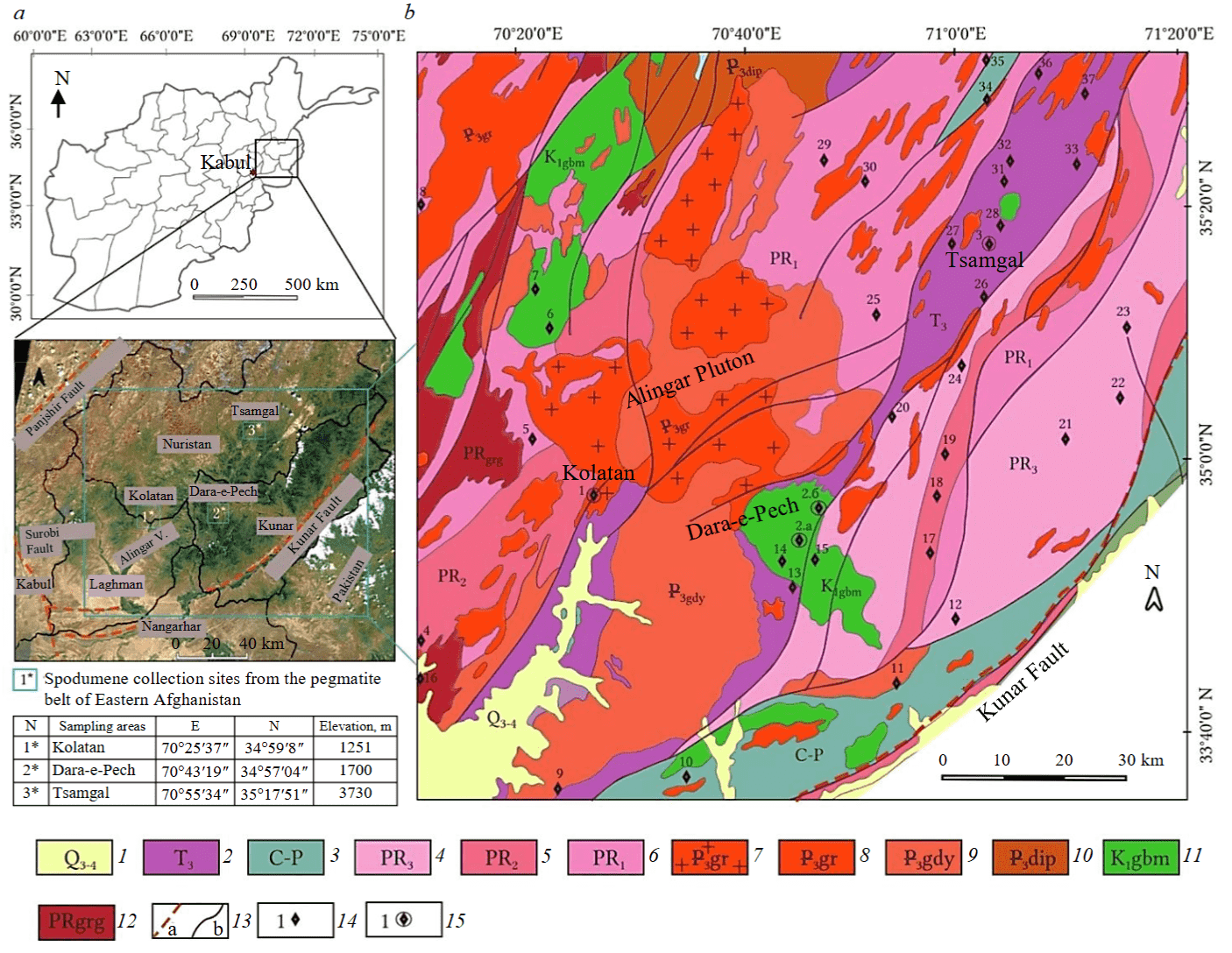

Large faults have mainly a north-eastern strike (Fig.1). Steeply dipping deep Panjshir faults in the northwest, Kunar in the southeast, Surobi in the southwest limit the Nuristan zone on three sides. The strike of the first two faults is N-E, the strike of the third is near-N-S.

In the Nuristan zone, intrusions of the Mesozoic-Cenozoic tectono-magmatic stages of magmatism are very widely developed. Early Cretaceous gabbro-monzonite-diorite rocks (Nilaw complex) and Oligocene granitoid batholiths (Laghman complex) are distinguished.

Oligocene granitoids of the Laghman complex are very widely developed in the Nuristan zone. They form several large and many small massifs developed among the metamorphic strata of the Nuristan series and Upper Triassic schists (Fig.1).

Fig.1. Placement of rare-metal pegmatites of the Laghman granitoid complex: a – location of the pegmatite belt of the Nuristan zone in Afghanistan (with a satellite image, where the research area and deposits are indicated by a rectangle); b – geological map of the central part of the pegmatite belt, compiled based on materials [19, 20, 31]

1 – alluvium, gravels, sands, and clays; 2 – phyllitic schists, siltstones and sandstones; 3 – sandstones, andesites, basalts; 4 – gneisses, schists, quartzites, amphibolites; 5 – marbles, gneisses, amphibolites, quartzites; 6 – gneisses, quartzites, amphibolites; magmatic formations, Laghman Oligocene complex: 7 – Alingar Pluton, granites-III; 8 – small massifs, lens-shaped and stock-like bodies, granites-III; 9 – granodiorite and granosyenites-II; 10 – diorites and plagiogranites-I; 11 – Nilaw complex, gabbro, monzonites, granodiorites and diorites;12 – Panjshir complex, granite gneisses; 13 – major faults (a), separating the Nuristan zone from other zones, and minor faults (b); 14 – pegmatite deposits: 1 – Kolatan, 2 – Dara-e-Pech: Digal (a), Gulsalak (b), 3 – Tsamgal, 4 – Alishang, 5 – Kurgal, 6 – Mavi, 7 – Nilaw-Kolam, 8 – Mandul, 9 – Charbagh, 10 – Darai Nur, 11 – Chaukai, 12 – Badel, 13 – Durahi; 14 – Avargal, 15 – Varadesh, 16 – Shamakat, 17 – Garangal,

The shape of the Laghman complex intrusions is predominantly oval and elongated in the north-eastern direction, less often close to isometric. The long axes of the massifs are parallel to each other and oriented conformable to the strike of the main structures in the region. The largest of the intrusions is the Alinghar Pluton traced over a distance of about 400 km.

The Laghman complex massifs are three-phase [18, 19]. The first phase is represented by diorites and quartz diorites, the second by porphyritic granites and granodiorites, the third by biotite, two-mica and aplite granites. The Laghman complex is notable for numerous rare-metal pegmatite veins, spatially associated with granitoids of the third phase [18-20]. Rare-metal pegmatites form pegmatite fields, which are grouped into large belts. The Nuristan and Hindu Kush pegmatite belts are associated with the Alinghar batholith [32].

Rare-metal pegmatite veins occur in the roof rocks of the granite massifs of the Laghman complex [33, 34], in the exocontact area, not in the granites themselves, but in the Late Triassic black schist strata: in quartz-chlorite-muscovite and phyllitic quartz-biotite-garnet-staurolite schists of the amphibolite facies. Fragmentarily hosting are the Early Cretaceous massifs of gabbro-diorites and quartz diorites of the Nilaw complex comprising two pegmatite fields – Dara-e-Pech and Nilaw-Kulam. A small number of veins are in the diorite and granodiorite massifs of the first phase of the Laghman complex. Pegmatites are rare in the Late Proterozoic dark grey sillimanite-garnet-biotite gneisses. However, the largest and most intensely mineralized bodies are localized in the Late Triassic phyllitic schists [21, 35].

Based on the composition of the main rock-forming and typomorphic minerals, pegmatites of the region are divided into the following main types [19, 20, 32]:

- oligoclase-microcline with biotite, muscovite, schorl, and rare beryl (barren);

- schorl-muscovite-microcline with ore-forming beryl;

- weakly albitized microcline with coarse-crystalline beryl;

- albite pegmatites with spodumene, polychrome tourmaline, kunzite, pollucite, and tantalite-columbite;

- spodumene-microcline-albite and spodumene-albite with polychrome tourmaline, kunzite, and pollucite;

- spodumene-lepidolite-clevelandite with cassiterite, pollucite, tantalite-columbite, and gemstones.

Rare-metal pegmatites in the Nuristan tectonic zone are distributed within three hypsometric levels:

- absolute height of 1200-2000 m – deposits of Shamakat, Kolatan, Kalagush, Nangalam, Tatang and others;

- absolute height of 2000-3400 m – deposits of Dara-e-Pech (Digal and Gulsalak), Tsamgal, Nilaw and others;

- absolute height of 3400-4500 m – deposits of Drumgal, Jamanak, Tsamgal, Pashki, Pasghushta, Yarigal in the Parun pegmatite field [33, 34].

Within the same pegmatite fields, individual pegmatite veins occur at different hypsometric levels.

To determine the differences in the compositions of lithium minerals from pegmatites of various hypsometric levels, the authors analysed spodumenes from three pegmatite deposits: Kolatan, Dara-e-Pech (Digal and Gulsalak), and Tsamgal in Eastern Afghanistan (Fig.1).

Of all the rare metal minerals, spodumene is the most widespread in the pegmatite belt of Eastern Afghanistan. It forms a large number of varieties, is found in different types of pegmatites and in various mineral associations – spodumene-microcline-albite, spodumene-albite, and spodumene-lepidolite-clevelandite.

The Kolatan deposit is in the lower part of the Titin River valley, the left tributary of the Alinghar River, 8 km northeast of Nangarach. The coordinates of the sampling points from the Kolatan deposit are 34°59'8'' N 70°25'37'' E. The topography is rocky, with absolute elevations above sea level ranging from 1251 to 1600 m. Oligocene granites of the Laghman complex, with which pegmatite veins are associated, are widespread. They occupy about 70 % of the area. The host rocks of the pegmatite veins, dark grey thin-layered quartz-chlorite-biotite-muscovite schists with garnet and staurolite, veins of rare-metal pegmatites are confined to a system of northeast and near-E-W striking fractures.

The Digal and Gulsalak deposits are in the central part of the Dara-e-Pech field, 40 km west of Asadabad, Kunar Province. Mesozoic-Cenozoic intrusions are widespread, with which spodumene veins are associated. Intrusive rocks occupy about 50 % of the area, with the Early Cretaceous gabbro-monzonite-diorites of the Nilaw complex and the Oligocene granites of the Laghman complex being prominent. The Nilaw complex intrusive rocks host pegmatite veins. Plagioclase-microcline veins are at the closest distance or in contact with the parent rock. Albitized microcline pegmatites with coarse-crystalline beryl are hypsometrically above them. The spodumene pegmatite veins occupy the highest hypsometric position within the field compared to pegmatites of other types. The pegmatite vein is tabular. The veins have massive and zoned internal structure. The topography in the region is rocky, absolute heights fluctuate from 1500 to 2400 m.

The Tsamgal deposit is in the area of the eastern exocontact of the Alinghar granite massif, in the central part of Nuristan Province, 15 km north of the town of Parun. The field area topography is strongly dissected, of the Alpine type, absolute heights fluctuate from 2600 to 4400 m. The Tsamgal deposit is a tabular spodumene vein, exposed by erosion downdip to a depth exceeding 500 m. Spodumene-microcline-albite pegmatite makes up the lower part of the vein. Higher in hypsometric level is the richer in lithium spodumene-albite deposit Pasghushta.

Internal structure and vertical zoning of spodumene pegmatites

Spodumene crystals have long prismatic shapes, often are perpendicular to the contacts of pegmatite veins, are sometimes replaced by cymatolite, and are rarely found in quartz-spodumene pseudomorphs after petalite.

The pegmatite bodies in the region form two groups by the nature and parameters of the vein bodies occurrence:

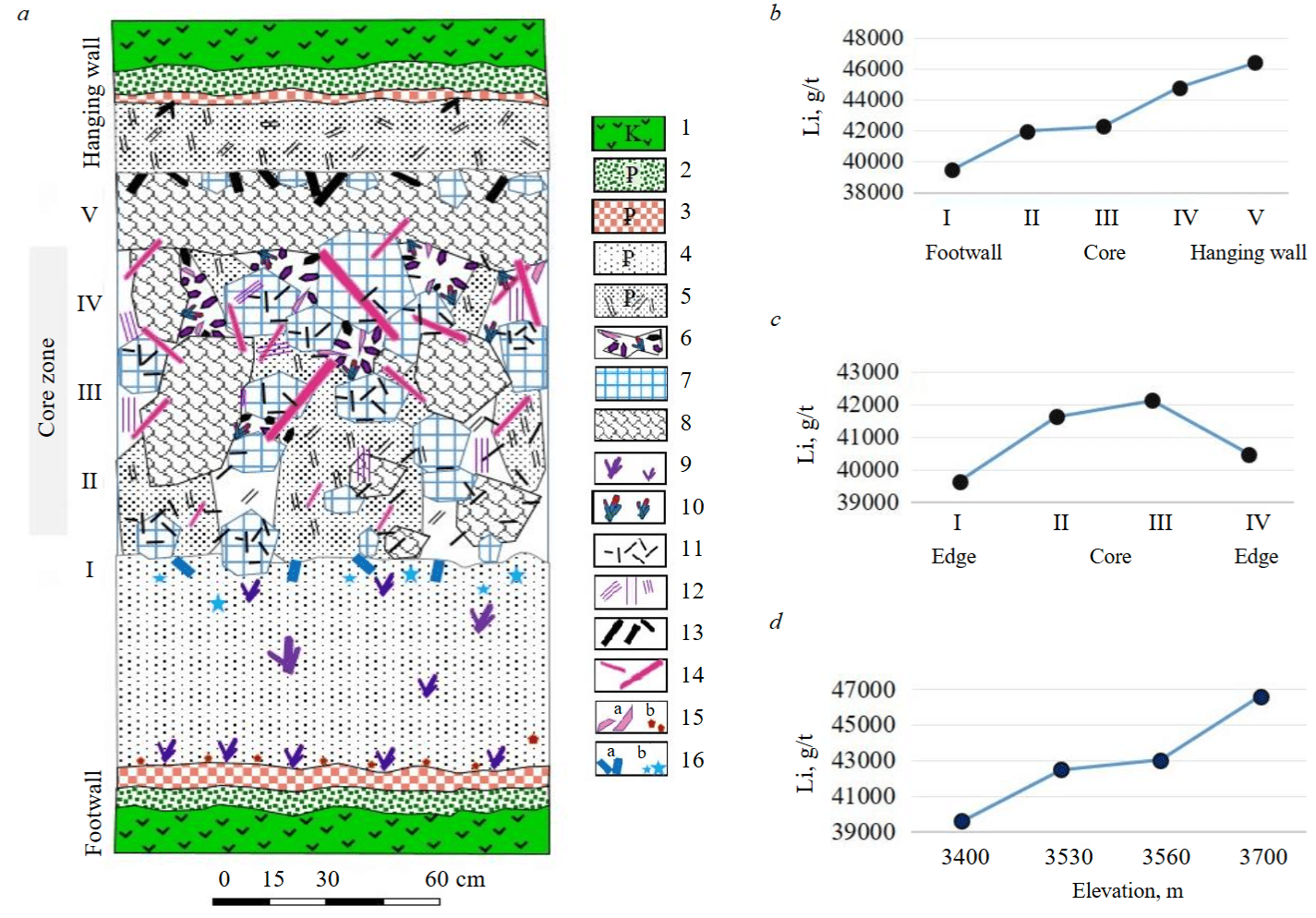

- steeply dipping veins, occurring mainly among phyllitic schists, having a symmetrical zoned structure, with relatively fine-crystalline minerals in the marginal zone, gradually replaced in the core by medium-grained and coarse-grained ones. The average lithium content in spodumene in the central part of the crystal is significantly higher (42,146 g/t) than in the marginal zones (39,640 g/t) (Fig.2, c). Such veins are rarely found among the intrusive rocks of the Nilaw complex gabbro-diorites;

- gently dipping veins, with an asymmetrical zoned structure, relatively fine-crystalline in the footwall, in the hanging wall they gradually become coarse-grained.

The average lithium content increases from the footwall (39,474 g/t) to the hanging wall (46,410 g/t) (Fig.2, b). The bulk of gently pitching pegmatites is among the Nilaw complex gabbro-diorites. The Dara-e-Pech and Nilaw-Kulam gem deposits are known here. The second variety of pegmatites is rarely found in gneisses and very rarely in schists.

One of the studied spodumene veins was exposed by erosion along the strike to 500 m. It is composed of 37 % albite, 34 % quartz, 15 % microcline, and 12 % spodumene. Muscovite, tourmaline, garnet, beryl, tantalite-columbite, cassiterite, and pollucite are also found (1-5 %). The average size of long prismatic spodumene crystals varies from 5 to 30 cm in length. The crystal colour is varied: white, dirty grey, white-pink, purple, and polychrome.

Coarse-grained whitish-pink spodumene is found in the block microcline-quartz core, and white spodumene is found mainly in the hanging wall, in muscovite-clevelandite aggregates. Around the mica nests, a concentration of small columbite-tantalite plates is observed. In such veins, spodumene is oriented mostly near-perpendicular to the vein selvages, but in general its orientation is not strict (Fig.2, a).

Fig.2. Internal structure and textural-paragenetic types of spodumene-microcline-albite pegmatite veins (a) with white and pink spodumene, kunzite, lepidolite, and polychromatic tourmaline from the Digal deposit in the Dara-e-Pech field (Eastern Afghanistan) and diagrams showing the distribution of average lithium content in spodumene from a gently dipping pegmatite vein (b) (zone numbers correspond to numbers in the cross-section); steeply dipping asymmetrical pegmatite vein of the Kolatan deposit (c): I – edge of the aplite zone; II – center of the blocky zone; III – quartz core; IV – edge of the graphic zone; veins occurring at different hypsometric levels as the distance from the granite massif increases, Tsamgal deposit (d)

The content of the element commercially significant for the pegmatites of Eastern Afghanistan, lithium, in spodumene is distributed unevenly, differentiation is observed in gently pitching veins in the hanging and foot selvages (Fig.2, b) – the minimum lithium concentration is in the foot flank of the vein and the maximum content is in the hanging flank. Such distribution of the ore component makes it possible to selectively mine lithium-rich spodumene ore from the upper horizons of gently dipping pegmatites.

Research methods and materials

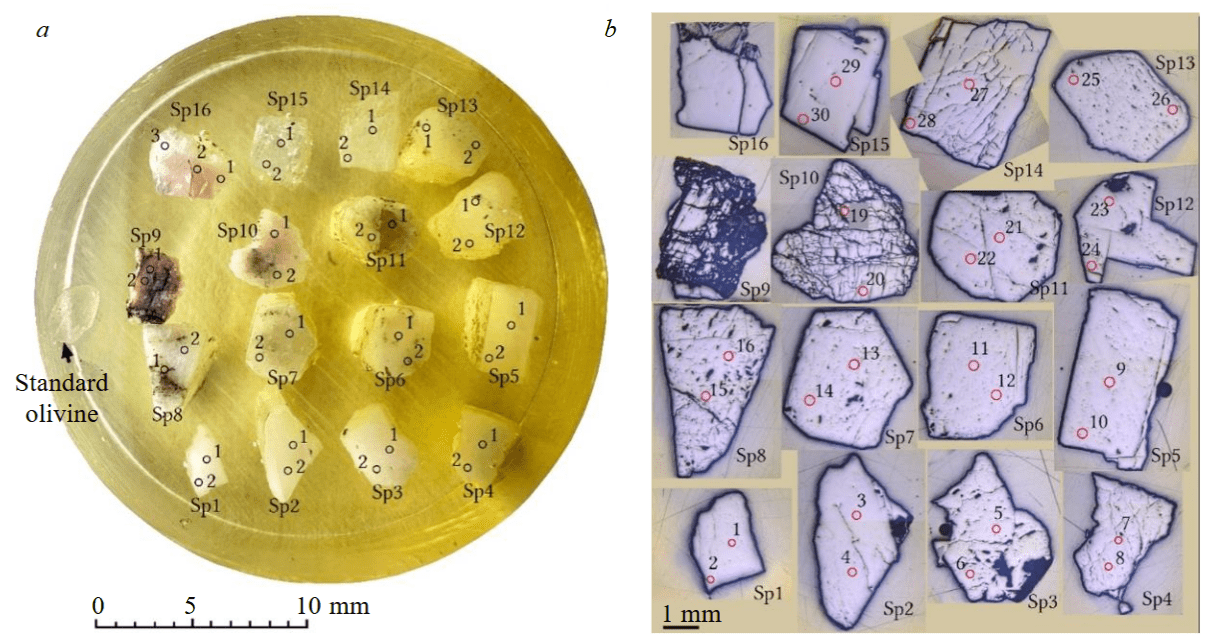

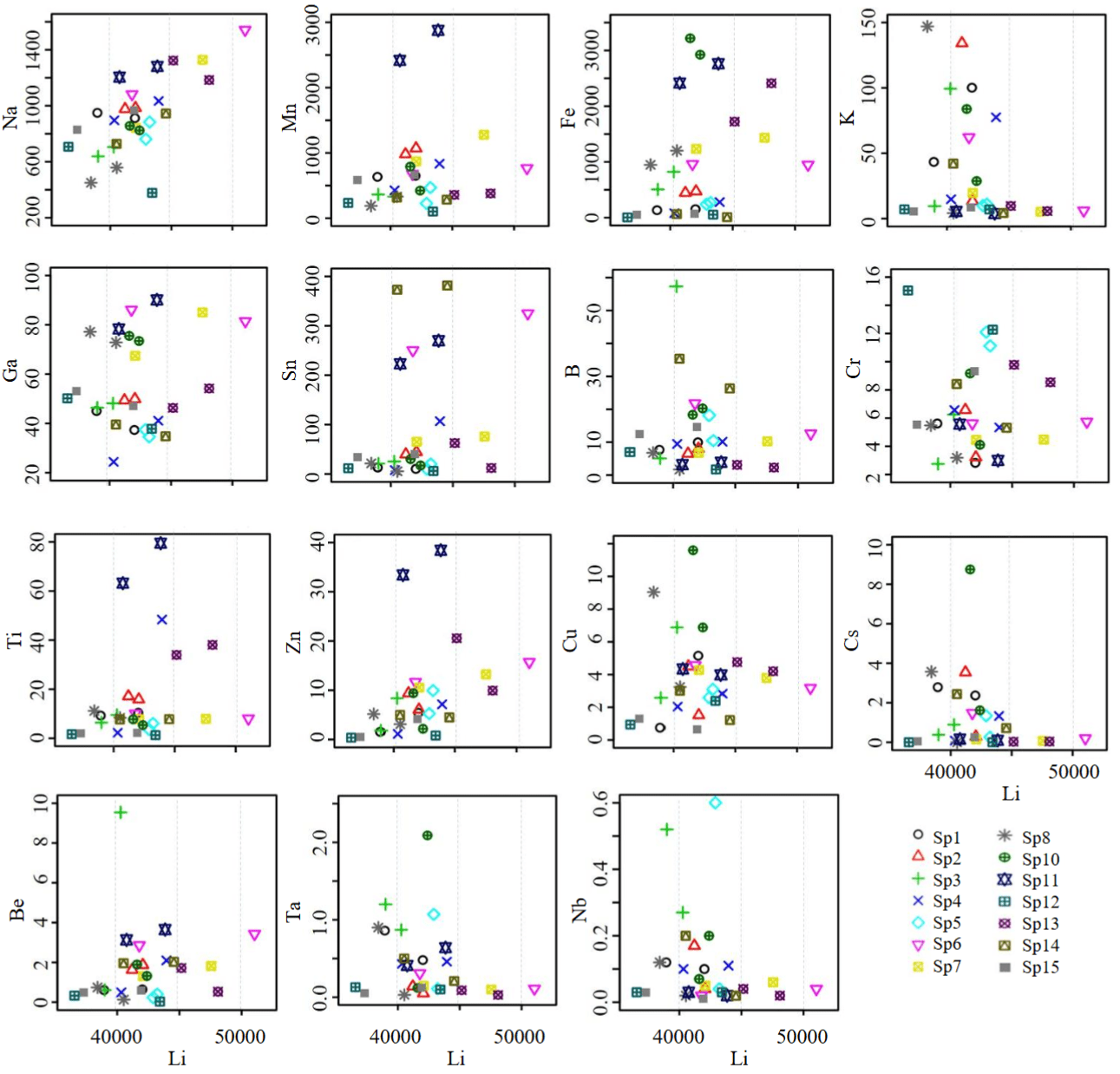

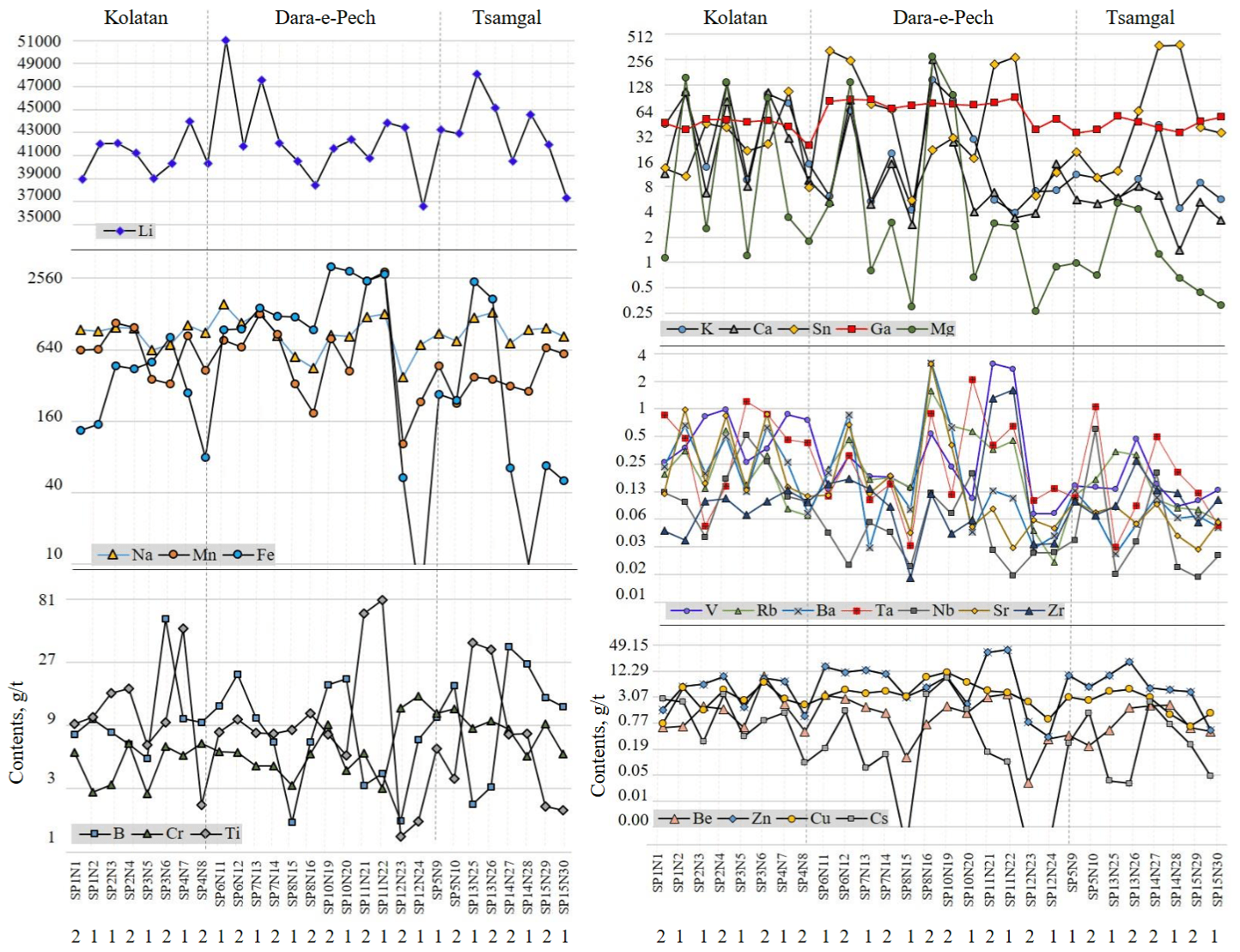

Four spodumene crystals (Sp1, Sp2, Sp3 and Sp4) from the Kolatan deposit were analysed; six crystals (Sp6, Sp7, Sp8, Sp10, Sp11 and Sp12) from the Digal and Gulsalak deposits; four crystals (Sp5, Sp13, Sp14 and Sp15) from the Tsamgal deposit. The Table and Fig.3, 4 clearly show the zoned distribution of minor and rare element contents.

Rare element composition of spodumene from the Kolatan, Digal, Gulsalak, and Tsamgal rare-metal pegmatite deposits of the Laghman granitoid complex, g/t

|

Tsamgal |

Sp15-30 |

1 |

37,305 |

828 |

588 |

50.7 |

5.62 |

53.1 |

3.20 |

34.5 |

12.5 |

5.52 |

2.07 |

0.31 |

0.52 |

1.31 |

0.05 |

0.49 |

0.13 |

0.06 |

0.05 |

0.05 |

0.03 |

0.06 |

0.10 |

0.09 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Sp15-29 |

2 |

41,935 |

969 |

664 |

67.3 |

8.75 |

47.1 |

5.16 |

40.0 |

14.7 |

9.3 |

2.20 |

0.44 |

4.13 |

0.65 |

0.25 |

0.60 |

0.10 |

0.08 |

0.07 |

0.12 |

0.01 |

0.03 |

0.06 |

0.10 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Sp14-28 |

1 |

44,555 |

945 |

285 |

9.88 |

4.36 |

34.8 |

1.39 |

381 |

26.3 |

5.32 |

7.83 |

0.65 |

4.50 |

1.22 |

0.72 |

2.03 |

0.09 |

0.08 |

0.06 |

0.21 |

0.02 |

0.04 |

0.12 |

0.03 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Sp14-27 |

2 |

40,514 |

729 |

319 |

65.1 |

42.1 |

39.6 |

6.24 |

373 |

35.4 |

8.42 |

7.69 |

1.25 |

4.99 |

3.01 |

2.44 |

1.96 |

0.15 |

0.10 |

0.11 |

0.50 |

0.20 |

0.09 |

0.13 |

0.20 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Sp13-26 |

2 |

45,154 |

1324 |

358 |

1723 |

9.64 |

46.3 |

7.95 |

62.6 |

3.09 |

9.78 |

34.0 |

4.28 |

20.6 |

4.76 |

0.03 |

1.72 |

0.47 |

0.32 |

0.05 |

0.09 |

0.04 |

0.06 |

0.27 |

4.81 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Sp13-25 |

1 |

48,099 |

1184 |

379 |

2412 |

5.71 |

54.2 |

5.89 |

12.2 |

2.30 |

8.54 |

38.1 |

5.05 |

9.93 |

4.20 |

0.04 |

0.53 |

0.13 |

0.34 |

0.03 |

0.03 |

0.02 |

0.09 |

0.09 |

6.36 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Sp5-10 |

2 |

42,905 |

762 |

226 |

239 |

9.95 |

37.4 |

4.96 |

10.2 |

18.2 |

12.1 |

3.57 |

0.70 |

5.28 |

2.59 |

1.34 |

0.23 |

0.14 |

0.17 |

0.07 |

1.07 |

0.60 |

0.07 |

0.07 |

1.06 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Sp5-9 |

2 |

43,221 |

884 |

468 |

272 |

11.0 |

34.6 |

5.50 |

20.3 |

10.5 |

11.1 |

6.06 |

0.98 |

9.94 |

3.10 |

0.26 |

0.40 |

0.14 |

0.11 |

0.13 |

0.11 |

0.04 |

0.10 |

0.10 |

0.58 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Digal, Gulsalak |

Sp12-24 |

1 |

36,571 |

707 |

234 |

4.48 |

7.10 |

50.2 |

14.9 |

11.7 |

7.0 |

15.1 |

1.69 |

0.89 |

0.37 |

0.94 |

b.d.l |

0.33 |

0.07 |

0.02 |

0.04 |

0.13 |

0.03 |

0.05 |

0.03 |

0.02 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Sp12-23 |

2 |

43,432 |

378 |

103 |

53.73 |

6.99 |

37.8 |

3.82 |

6.12 |

1.72 |

12.3 |

1.30 |

0.26 |

0.81 |

2.39 |

b.d.l |

0.03 |

0.07 |

0.05 |

0.03 |

0.10 |

0.03 |

0.06 |

0.03 |

0.52 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Sp11-22 |

1 |

43,851 |

1281 |

2877 |

2762 |

3.86 |

90.0 |

3.38 |

270 |

3.89 |

3.0 |

79.5 |

2.68 |

38.4 |

3.98 |

0.10 |

3.65 |

2.74 |

0.45 |

0.11 |

0.64 |

0.02 |

0.03 |

1.60 |

0.96 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Sp11-21 |

2 |

40,754 |

1205 |

2417 |

2415 |

5.50 |

78.3 |

6.75 |

223 |

3.18 |

5.57 |

63.2 |

2.87 |

33.4 |

4.34 |

0.16 |

3.13 |

3.11 |

0.36 |

0.13 |

0.41 |

0.03 |

0.08 |

1.31 |

1.00 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Sp10-20 |

1 |

42,394 |

824 |

424 |

2925 |

28.7 |

73.4 |

3.99 |

17.2 |

20.3 |

4.11 |

5.38 |

0.65 |

2.17 |

6.88 |

1.62 |

1.32 |

0.11 |

0.57 |

0.05 |

2.09 |

0.20 |

0.05 |

0.06 |

6.90 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Sp10-19 |

2 |

41,595 |

857 |

790 |

3219 |

83.9 |

75.5 |

27.1 |

30.2 |

18.3 |

9.17 |

7.74 |

96.2 |

9.41 |

11.60 |

8.75 |

1.89 |

0.23 |

0.65 |

0.63 |

0.12 |

0.07 |

0.40 |

0.04 |

4.07 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Sp8-16 |

2 |

38,420 |

450 |

189 |

948 |

147 |

77.2 |

258* |

21.5 |

6.77 |

5.48 |

11.2 |

276 |

5.17 |

9.04 |

3.57 |

0.74 |

0.53 |

1.56 |

3.17 |

0.90 |

0.12 |

3.09 |

0.12 |

5.02 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Sp8-15 |

1 |

40,529 |

559 |

331 |

1202 |

4.22 |

72.8 |

2.81 |

5.52 |

1.69 |

3.19 |

8.38 |

0.29 |

3.09 |

3.24 |

b.d.l |

0.13 |

0.14 |

0.14 |

0.08 |

0.03 |

0.02 |

0.04 |

0.01 |

3.63 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Sp7-14 |

2 |

42,084 |

842 |

870 |

1233 |

19.6 |

67.4 |

14.8 |

65.1 |

6.76 |

4.46 |

7.82 |

2.95 |

10.6 |

4.28 |

0.15 |

1.31 |

0.18 |

0.18 |

0.17 |

0.15 |

0.05 |

0.18 |

0.09 |

1.42 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Sp7-13 |

1 |

47,557 |

1328 |

1278 |

1433 |

5.25 |

85.1 |

4.93 |

76.2 |

10.3 |

4.48 |

7.91 |

0.80 |

13.2 |

3.79 |

0.07 |

1.82 |

0.18 |

0.17 |

0.03 |

0.10 |

0.06 |

0.12 |

0.14 |

1.12 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Sp6-12 |

2 |

41,779 |

1082 |

679 |

961 |

62.2 |

86.0 |

84.5 |

251 |

21.8 |

5.62 |

10.1 |

136 |

11.7 |

4.57 |

1.48 |

2.86 |

0.31 |

0.46 |

0.86 |

0.31 |

0.02 |

0.67 |

0.17 |

1.42 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Sp6-11 |

1 |

51,040 |

1542 |

767 |

948 |

6.11 |

81.4 |

5.30 |

325 |

12.6 |

5.74 |

8.04 |

4.93 |

15.7 |

3.18 |

0.20 |

3.43 |

0.13 |

0.22 |

0.20 |

0.11 |

0.04 |

0.11 |

0.15 |

1.24 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Kolatan |

Sp4-8 |

2 |

40,331 |

896 |

427 |

79.8 |

14.8 |

24.4 |

9.46 |

7.80 |

9.46 |

6.57 |

2.27 |

1.78 |

1.13 |

2.04 |

0.09 |

0.49 |

0.75 |

0.07 |

0.07 |

0.43 |

0.10 |

0.11 |

0.10 |

0.19 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Sp4-7 |

1 |

43,962 |

1034 |

834 |

279 |

77.5 |

41.1 |

29.6 |

107 |

10.1 |

5.34 |

48.4 |

3.38 |

7.15 |

2.83 |

1.33 |

2.10 |

0.87 |

0.08 |

0.26 |

0.46 |

0.11 |

0.14 |

0.13 |

0.33 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Sp3-6 |

2 |

40,277 |

706 |

329 |

821 |

99.4 |

48.2 |

105 |

25.4 |

57.3 |

6.25 |

9.52 |

89 |

8.37 |

6.88 |

0.89 |

9.54 |

0.37 |

0.31 |

0.63 |

0.87 |

0.27 |

0.88 |

0.10 |

2.49 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Sp3-5 |

1 |

39,003 |

639 |

363 |

507 |

9.53 |

46.4 |

7.93 |

21.2 |

5.08 |

2.75 |

6.42 |

1.20 |

1.82 |

2.58 |

0.38 |

0.61 |

0.26 |

0.15 |

0.12 |

1.20 |

0.52 |

0.13 |

0.07 |

1.40 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Sp2-4 |

2 |

41,211 |

977 |

980 |

444 |

134 |

49.4 |

80.4 |

39.8 |

6.51 |

6.58 |

17.1 |

136 |

9.39 |

4.50 |

3.54 |

1.63 |

0.98 |

0.58 |

0.50 |

0.14 |

0.17 |

0.84 |

0.11 |

0.45 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Sp2-3 |

1 |

42,063 |

985 |

1071 |

472 |

13.4 |

49.9 |

6.65 |

44.4 |

7.99 |

3.22 |

15.9 |

2.50 |

6.07 |

1.52 |

0.29 |

1.87 |

0.83 |

0.14 |

0.20 |

0.05 |

0.04 |

0.15 |

0.10 |

0.44 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Sp1-2 |

1 |

42,017 |

912 |

650 |

152 |

100 |

37.3 |

105 |

10.6 |

9.96 |

2.83 |

10.4 |

155 |

5.43 |

5.15 |

2.37 |

0.64 |

0.38 |

0.35 |

0.66 |

0.48 |

0.10 |

0.98 |

0.04 |

0.23 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Sp1-1 |

2 |

38,941 |

950 |

634 |

134 |

43.4 |

45.0 |

11.4 |

13.2 |

7.69 |

5.62 |

9.25 |

1.13 |

1.56 |

0.75 |

2.79 |

0.61 |

0.26 |

0.20 |

0.23 |

0.86 |

0.12 |

0.12 |

0.05 |

0.21 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Element |

Li |

Na |

Mn |

Fe |

K |

Ga |

Ca |

Sn |

B |

Cr |

Ti |

Mg |

Zn |

Cu |

Cs |

Be |

V |

Rb |

Ba |

Ta |

Nb |

Sr |

Zr |

Fe/Mn |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes: 1 – marginal part of the crystal; 2 – central part of the crystal; b.d.l. – below detection limit; the asterisk notes Ca content in a crystal with microinclusion.

Fig.3. Macrophotographs (a) and microphotographs in reflected light (b) of spodumene samples from the Kolatan, Dara-e-Pech, and Tsamgal deposits, indicating the locations of analytical points

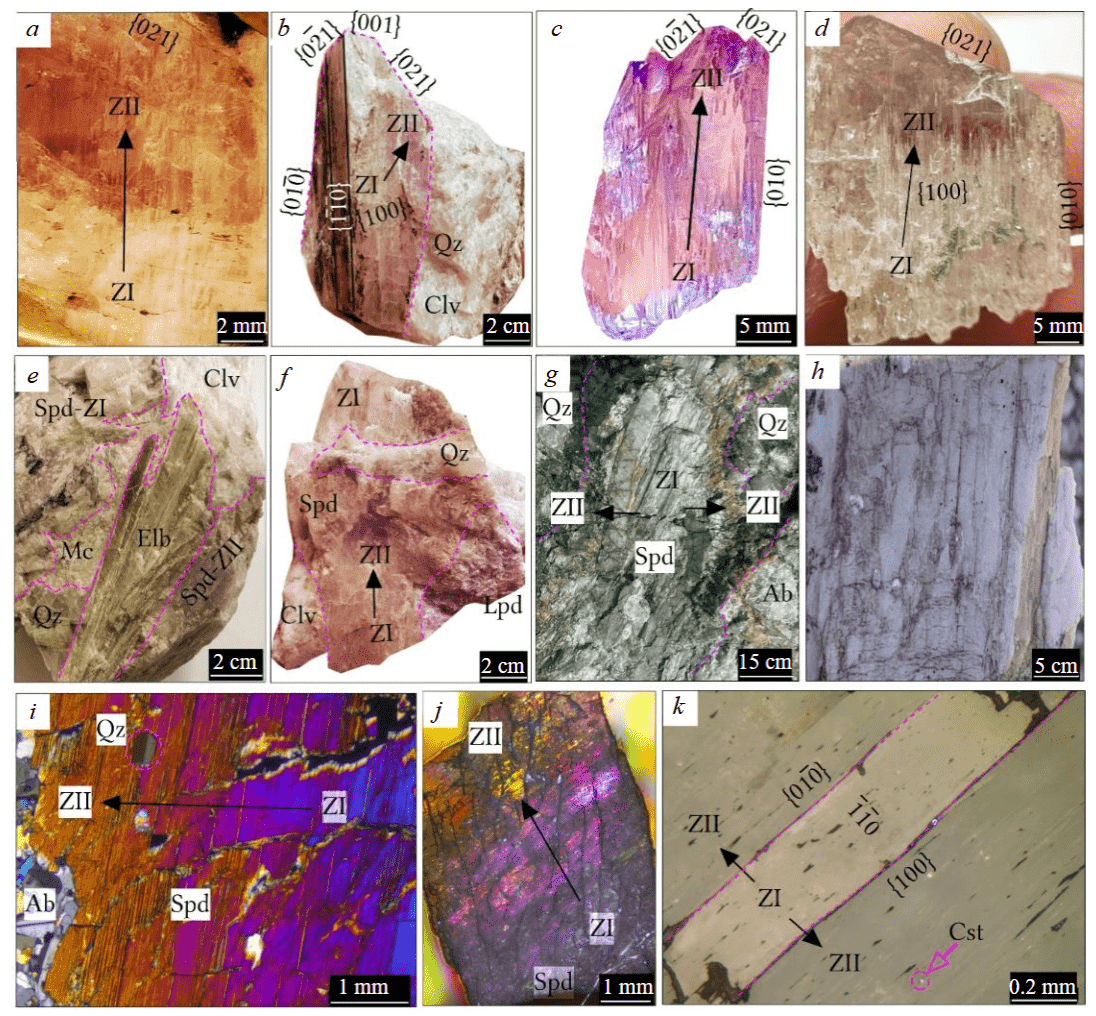

Fig.4. Structural-textural features and zonation of spodumene from the Kolatan (b, e, f, j), Dara-e-Pech (a, c, i, k) and Tsamgal (d, g, h) deposits shown in macrophotographs (a-h) and microphotographs (i-k). The color gradually changes from the crystal center (ZI) to the edge (ZII): polychromatic (from white to violet) with glassy luster (a, b); pinkish-violet with vertical striations (c); colorless with vertical striations (d); light-gray (e); white (f); dirty grayish-green (g); pinkish-white prismatic spodumene crystals in transmitted (i) and reflected light (j, k) Ab – albite; Clv – cleavelandite; Cst – cassiterite; Elb – elbite; Mc – microcline; Qz – quartz; Spd – spodumene; Ta-Nb –tantaline-columbite; Lpd – lepidolite

Spodumene crystal structure was investigated by Leica DM 2500M in transmitted and reflected light [36-38]. Diagnostics of inclusions in spodumene was performed using Raman spectroscopy with a Renishaw InVia Raman spectrometer [22, 39] at the Saint Petersburg Mining University.

The contents of rare and trace elements were determined by secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS) using a Cameca IMS-4f ion probe at the Yaroslavl branch of the Valiev Institute of Physics and Technology of the RAS. Survey conditions: primary beam of 16О2¯ ions with a diameter of approximately 20 μm; ion current 5-7 nA; accelerating voltage of the primary beam 15 keV. Each measurement consisted of three cycles, which made it possible to estimate the individual measurement error. The total analysis time for one point averaged 30-40 min. The measurement error of rare elements is up to 10 % for concentrations above 1 ppm and up to 20 % for the concentration range of 0.1-1 ppm; the detection threshold for different elements varies within 5-10 ppb. The method for measuring the content of minor and rare elements is described in detail in [40-42]. When making the preparation, spodumene crystals were cut perpendicular to the 1 prism faces and pinacoid faces, parallel to the 100 and 8 axes. The objectives of the investigation included studying the growth zoning and sectorial structure of spodumene from the centre towards the edge of the crystal in a plane parallel to the basopinacoid. Spodumene crystal fragments were placed in standard disks together with olivine grains, which was necessary for assessing the background when analysing the content of volatile components.

Results

Based on geochemical, macro- and microscopic studies, considering the morphological features of minerals and their confinement to certain mineral associations, three varieties of spodumene were identified in the study area: opaque spodumene of early and late generations, the main commercial mineral of lithium ores in spodumene-microcline-albite and spodumene-albite pegmatites, ore-forming; finely crystalline acicular spodumene, the main rock-forming mineral of aphanitic dikes; transparent spodumene of gem-quality in miarolitic cavities of the quartz core in spodumene-microcline-albite and spodumene-lepidolite-clevelandite pegmatites.

The size of opaque spodumene crystals of the first variety varies from 5 to 25 cm in length. The largest crystals in the central parts of block pegmatites reach 1-1.5 m, sometimes to 2 m in length. The crystals are prismatic, board-shaped, lamellar, short-columnar. Crystal heads are often found. The largest board-shaped crystal measuring 10×30×150 cm was found in the Kolatan deposit. Quartz-spodumene pseudomorphoses after petalite are usually observed in paragenesis with microcline and fine-lamellar albite in associations where, in addition to them, clevelandite, muscovite, coloured tourmaline, minerals of the tantalite-columbite group are present. The crystal colours are white, pink, purple, grey, dirty green, grey-green. Predominant long-prismatic spodumene is of dirty green and green colours.

Aggregates of acicular spodumene under the microscope reveal a paniculate, felt-like structure and in the form of a solid mass replace petalite, early spodumene, pseudomorphs of spodumene and quartz after petalite and even albite aggregates. Fine-crystalline acicular spodumene was found only by microscopic studies in thin sections. It has a limited distribution in the valleys of Alinghar, Dara-e-Pech, and Parun, and is widespread in the Alishang valley deposit. The crystal size varies from 0.01 to 0.5 mm, the shape is isometric and elongated, the colour is white with a greenish tint.

In the studied area, gem spodumene is represented by varieties with different properties and compositions: kunzite – from pink to purple, green hiddenite and tryphan – from colourless to yellow, distinguished by strong pleochroism [14, 43, 44].

Kunzite occurs mainly in veins of albite-spodumene-microcline pegmatites in paragenesis with lepidolite, blue clevelandite, rock crystal, vorobyevite, polychrome tourmaline, and sometimes with pollucite (Fig.4). Crystals are of thin tabular, board-like, thick tabular, and prismatic shapes. Crystal heads are common, and most crystals have well-developed vertical striations (Fig.4, c, d). Transparent and violet kunzite has Ng 1.675, Nm 1.662, Np 1.658, and Ng-Np 0.017, +2V 56°. The crystal size varies from 3×8×12 mm to 2.5×12×25 cm, and larger ones are rare. The colour of gem spodumenes is varied: colourless, pink- and reddish-violet, crimson, green, bluish- and light bluish-green, yellow and blue. Sometimes a combination of several colours is observed in one crystal.

Spodumene from the Kolatan deposit

In the Kolatan deposit, spodumene (Sp1, Sp2, Sp3, Sp4) occurs in spodumene-microcline-albite and spodumene-lepidolite-clevelandite veins with pollucite, amblygonite, tantalite-columbite (Ta and Nb minerals), cassiterite, and polychrome tourmaline. It is widespread in quartz-spodumene zones. Spodumene content in the veins varies from 15 to 30 %. Spodumene is long-prismatic and tabular, white, greyish-white and white-pink, violet, and polychrome. The crystal length averages from 10-30 to 15-70 cm, sometimes board-shaped spodumene crystals reach 130-150 cm.

The analysis showed that spodumene composition changes sharply – both macro- and microelements (Li, Na, Mn, Ga, Sn, Ti, Zn) increase from the centre to the periphery of the crystals and decrease from the centre to the edge of the crystals (Fe, K, Ca, B, Cr, Mg, Cu, Cs, Be). The most significant changes in content are noted for Li (38,941-43,962), Na (639-1034), Mn (329-1071), Fe (79.8-821), K (9.53-134), Ga (24.4-49.9), Ca (6.65-105), Sn (7.8-106), Mg (1.13-155.4), B (5.08-57.3), Ti (2.27-48.4) ppm. Lower variations in content have Cr (2.75-6.58), Zn (1.13-9.39), Cu (0.75-6.88), Cs (0.09-3.54), Be (0.49-9.54), Ta (0.05-1.2), Sr (0.11-0.98) ppm. Concentrations of V, Rb, Ba, Nb, Zr are less than 0.5 ppm.

Spodumene from the Digal and Gulsalak deposits

Spodumene samples Sp6 and Sp7 were collected from the Gulsalak deposit, the coordinates of the site centre are 34°57'56'' N 70°44'16'' E. Spodumene crystals Sp8, Sp10, Sp11, Sp12 were collected from the Digal deposit, the coordinates of the site centre are 34°57'04'' N 70°43'19'' E.

Analysis of the distribution of macro- and microelements shows that in spodumene from the Digal and Gulsalak deposits their contents in the marginal zones and the centre of the crystals are of a contrasting nature, just like in the Kolatan deposit: the highest fluctuations in contents – an increase from the centre to the edge of the crystals (Li, Na, Fe, Mn, Ga, Sn, Ti, Zn, Be) and a decrease from the centre to the edge (K, Ca, B, Cr, Mg, Cu, Cs) – are characteristic of Li (36,571-51,039), Na (378-1542), Mn (103-2877), Fe (53.7-3219), K (3.86-146), Ga (37.8-90.0), Ca (2.81-257), Sn (5.52-325), Mg (0.26-275), B (1.69-21.8), Ti (1.3-79.5) ppm. Cr (3.0-15.0), Zn (0.37-38.43), Cu (0.94-11.6), Cs (0.01-8.75), Be (0.03-3.65), Ta (0.03-2.09), V (0.07-3.11), Sr (0.03-3.09), Rb (0.02-1.56), Ba (0.03-3.17), Zr (0.011.60) ppm contents change less. Nb content is less than 1 ppm.

The amount of V fluctuates from 0.07 to 0.98 g/t in all spodumenes except Sp11, where it significantly increases to 2.73-3.1 g/t. In addition, Zr and Mg content is noticeably higher – Zr 1.3-1.6, Mg 2417-2876 g/t. In the remaining spodumenes, low contents of Zr 0.01-0.27, Mg 103-1278 g/t are observed. In the marginal part of sample Sp8, the contents of Sr 0.04, Ba 0.08, Rb 0.14, Mg 0.29, and K 4.22 g/t are noticeably lower than in the central part of Sp8: Sr 3.09, Ba 3.17, Rb 1.56, Mg 276, and K 147 g/t. In the remaining samples, the contents of these elements vary in the ranges Sr 0.03-0.88, Ba 0.03-0.65, Rb 0.02-0.65, Mg 0.16-26, Ca 1.05-1.38, K 3.85-134 g/t.

Spodumene from the Tsamgal deposit

The pegmatite bodies from which the spodumene crystal samples were collected have the following coordinates: Sp5 – 35°15'31'' N 70°55'28.4'' E; Sр12, Sр13, Sр14, Sр15 – 35°17'25'' N 70°59'46'' E. Spodumene from the Tsamgal deposit is greenish-grey, greyish-green, dirty-green. The crystals are long-prismatic. The crystal length varies on average from 5 to 25 cm. Spodumene occurs in paragenesis with microcline in albitized regions of pegmatite veins. Spodumene content in the vein is 10-30 %. Spodumene crystals are clearly oriented perpendicular to the vein contacts.

Determination of macro- and microelement compositions of spodumenes at different sampling points showed a pattern identical to that in similar deposits. The highest fluctuations in contents – an increase from the centre to the edge of the crystals (Li, Na, Fe, Mn, Mg, Ga, Ti) and a decrease from the centre to the edge (K, Ca, B, Cr, Cu, Sn, Zn, Be) – are observed for Li (37,304-48,098), Na (729-1324), Mn (226-664), Fe (9.88-2412), K (4.36-42.1), Ga (34.5-54.1), Ca (1.39-7.95), Sn (10.1-381), Mg (0.31-5.05), B (2.30-35.4), Ti (2.07-38.1) ppm. Relatively low variations in content are observed for Cr (5.32-12.1), Zn (0.52-20.8), Cu (0.65-4.76), Cs (0.03-2.44), Be (0.23-2.03), Ta (0.03-1.07) ppm. The content of Sr, V, Rb, Ba, Nb, Zr is less than 1 ppm.

Discussion

The correlation diagrams (Fig.5) show the ratios of Li and rare element contents in spodumenes. Lithium content in spodumene shows a positive correlation with Na, Mn, Fe, Ga, Sn, B, Ti, Zn, Cu, Be and a negative correlation with K, Cs, Ta, Nb, Cr. Compared with all other elements, sodium has a strong positive correlation with lithium content in spodumene, while other elements do not have such a dependence, or it is very weak.

Fig.5. Correlation diagrams of the relationship between trace and rare element contents and Li in spodumene from the deposit of Kolatan (Sp1, Sp2, Sp3, and Sp4), Dara-e-Pech (Sp6, Sp7, Sp8, Sp10, Sp11, and Sp12) and Tsamgal (Sp5, Sp13, Sp14, and Sp15) of the Nuristan zone, g/t

Spodumene crystals in pegmatites of Eastern Afghanistan have different colours, sometimes clearly zoned. This is due to changes in the amount of impurities in different zones of the crystals. In the studied spodumene samples collected in the Dara-e-Pech region, the distribution of magnesium looks contrasting. The amount of Mg in the marginal part is 0.25-4.93 g/t, increasing to 276 g/t in the crystal centre. In spodumene from the Kolatan deposit, there is no noticeable change from the marginal parts to the centre: 1.2-155 g/t in the marginal part and 1.13-137 g/t in the central part. The same is true for grains from the Tsamgal deposit – in the marginal zone of the spodumene grain Mg is 0.31-5 g/t, in the central, 0.44-4.28 g/t. Here, a negative correlation is observed between Na and Mg and a sharply positive one between Mg and Ca, which is explained by isomorphism of these elements.

Ga content in spodumene from the Kolatan deposit varies within 24-49 g/t, 43 g/t on average; Dara-e-Pech – from 39-90 g/t, 73 g/t on average; Tsamgal – 35-54 g/t, 43 g/t on average. Ga is the only rare element in spodumene that does not demonstrate relatively stable content in the marginal central zones of crystals. Ga content in spodumene from the microcline-spodumene-albite veins of the Dara-e-Pech deposit is significantly higher compared to spodumene from the lepidolite-clevelandite-spodumene veins of the Kolatan and Tsamgal deposits (Fig.6).

For spodumenes from lithium pegmatites of Afghanistan, zoning caused by changes in the amount of minor and rare element impurities is very typical in comparison with spodumenes from other countries. This makes Afghan spodumenes similar to minerals from the Chinese deposits. For example, the distribution of transition elements in spodumene from the Lhozhag deposit (China) shows similar variability in Sn, Mg, Fe, and Ti content [29, 45, 46]. In contrast, zoning is not manifested in spodumenes from the Kolmozerskoe deposit in Russia [45].

Fig.6. Distribution of lithium, trace and rare elements in the marginal (1) and central (2) parts of spodumene crystals, indicating the positions of analytical points

The amount of Mn in spodumenes from the studied deposits is significantly higher than in spodumene deposits of Russia, Kazakhstan, and other countries. On the contrary, the amount of Fe in spodumene from the Kolmozerskoe deposit is higher than in spodumenes from Afghanistan. The Fe/Mg correlation of spodumene from the Kolmozerskoe deposit corresponds to greenish-grey spodumene from the Tsamgal deposit. The Sn correlations correspond to those of pink spodumene from the Kolatan deposit and grey spodumene from the Dara-e-Pech deposit.

Spodumene has two non-equivalent metal cations M1 and M2 in one crystallographic plane [23]. Al and Li can be replaced by ions of transition metals Mn, Fe, Cr in various ratios, therefore, the colours of spodumene associated with impurities can be quite diverse (Fig.4, 7) [14]. Mn2+ is found mainly in areas enriched in lithium, not aluminium, and gives a broad emission centred at 600 nm [23]. In crystals rich in Cr, only one R1 line is observed, and Cr3+ emission is noticeable at room temperature.

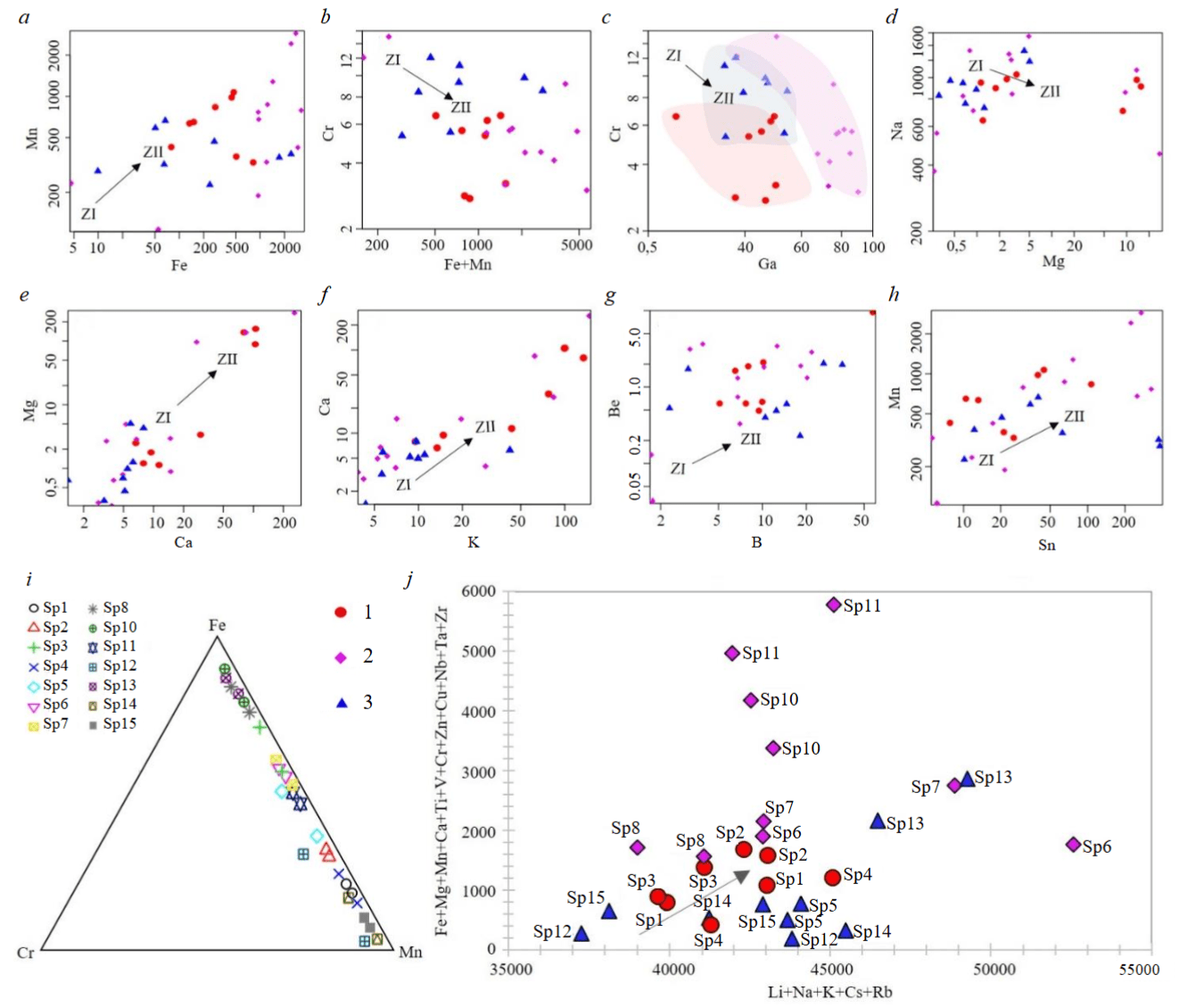

Some researchers [42] suggest that Mn3+ occupies the M2 site of monoclinic symmetry, while others [44] suggest that it may occupy the M1 site if introduced into the spodumene lattice during crystal growth.

Fig.7. Ratios of minor and rare elements, alkali and transition elements in spodumene on binary and ternary diagrams, g/t: Mn/Fe (a), Cr/Fe+Mn (b), Cr/Ga (c), Na/Mg (d), Mg/Ca (e), Ca/K (f), Be/B (g), Mn/Sn (h) and Fe/Cr/Mn (i) in the central (ZI) and marginal zones (ZII) of spodumene crystals from the Kolatan (1), Dara-e-Pech (2), and Tsamgal (3) deposits; alkali to transition element ratio (j)

According to [14], based on the study of the chemical composition and optical properties, we can talk about two varieties of gem spodumene: green chromium spodumene (typical of deposits in North Carolina, USA) and chromium-free spodumene (colourless, yellow, pink, purple or green – natural or synthetic). Studies show that the main chromophores of spodumene are Mn, Fe, Cr, V and sometimes Co [23, 42, 47]. Figure 7 shows the Fe–Mn–Cr, Cr–Cu–Fe/Mn, Ti, and Ga bonds of spodumene from the Kolatan, Dara-e-Pech, and Tsamgal deposits.

Average Fe content in spodumene from the Kolatan deposit is 361 g/t, Dara-e-Pech – 1805 g/t; Tsamgal – 605 g/t. The distribution of Fe in the marginal zone does not change as sharply as that of Mn. The correlation between Mn/Fe is positive (Fig.7, a). Lighter zones compared to dark ones are characterized by a higher Fe/Mn ratio – 0.03-6.9 g/t. A positive correlation is also noted between Mn and Sn (Fig.7, h). In the pinkish-violet zones of the crystal, Mn content is significantly higher than Fe content.

The lilac colour of spodumene appears at a higher Mn/Fe ratio – from 1 g/t [23, 48]. In this case, spodumene (kunzite) acquires a pinkish-lilac hue, which has a higher gem value. The Mn/Fe ratio in spodumene from the Kolatan deposit fluctuates from 2.2-5.35 g/t, except for Sp3 – 0.4-0.72 g/t. The Mn/Fe ratio in spodumene from Dara-e-Pech (Sp6, Sp7, Sp8, and Sp10) fluctuates from 0.14 to 0.89 g/t, in Sp11 1.0-1.04 g/t, and in Sp12 it significantly increases to 1.92-52.3 g/t. This crystal has a sharply zoned colour from white to pinkish-violet. The Mn/Fe ratio in Tsamgal spodumene varies in Sp5 0.95-1.72, Sp13 0.16-0.21, Sp14 4.9-28.8, Sp15 9.88-11.6 g/t.

Average Cr content in spodumene from the Kolatan deposit is 4.9 g/t, Dara-e-Pech – 6.5 g/t, Tsamgal – 8.8 g/t (dirty green) (see Fig.4, g). The correlations between Cr/Fe, Cr/Mn, and Cr/Ga are negative (Fig.7, b, c). In general, spodumene is depleted in chromium (Fig.7, i), and the change in colour is associated with change in the content mainly of manganese and iron. The correlations between Ca/K, Be/B Mn/Fe, Mn/Sn, and Mg/Ca are positive (Fig.7).

Ta content in all spodumenes fluctuates between 0.05-1.2 g/t, increasing to 2 g/t in the marginal part of Sp2. High Be content in the central part of Sp3 is 9.54 g/t and decreases to 0.61 g/t towards the marginal part. In the remaining spodumene samples, Be content is 0.13-3.65 g/t in the marginal part and 0.03-3.13 g/t in the central part.

In the distribution of Mn, Sn, Ti contents, a tendency of significant increase from the central to the marginal part of the crystals is observed. On the contrary, Cr, Fe, Mg, K, Ca, Cu, B contents decrease significantly from the central to the marginal part of the crystals.

In the spodumenes from the Kolatan deposit, a clear sharp increase in the content of Mn (on average 729 g/t in the marginal part (ZII) and 593 g/t in the central (ZI), Fe (352 and 370 g/t), Cr (3.53 and 6.25 g/t), K (50.1 and 72.9 g/t), Sn (45.7 and 21.5 g/t), Ca (37.4 and 51.4 g/t), Ti (20.2 and 9.54 g/t), Mg (40.6 and 57.1 g/t), B (8.29 and 20.2 g/t), Ga (43.7 and 41.7 g/t), and Be (1.3 and 3.07 g/t) is observed. The most contrasting change in the distribution nature is manifested in the contents of Mn, Fe, Cr, K, Sn, Ca, Ti, Mg, B, and Be at the conventional boundary between two simple forms (pinacoid in the central part of the section perpendicular to the crystal elongation axis, and prism in the marginal part).

In spodumenes from the Dara-e-Pech deposit (Digal and Gulsalak), a clear sharp increase in the contents of Mn (on average 985 g/t for the marginal part (ZII) and 841 g/t for the central part (ZII)), Fe (1546 and 1472 g/t, respectively), Cr (5.93 and 7.09 g/t), K (9.21 and 54.1 g/t), Na (1040 and 802 g/t), Sn (117 and 99 g/t), Ca (5.88 and 65.8 g/t), Ti (18.5 and 16.9 g/t), Mg (1.71 and 85.7 g/t), Ga (75.5 and 70.4 g/t), Cs (0.33 and 2.35 g/t), and Cu (3.67 and 6.04 g/t) is observed. At the conventional boundary between the pinacoid (in the centre) and the prism (in the marginal part), the contents of Mn, Fe, Cr, K, Na, Sn, Ca, Ti, Mg, Ga, Cs, and Cu change noticeably.

In spodumene crystals from the Tsamgal deposit, a sharp increase in the content of the following elements is observed from the edge to the centre: Mn (on average from 392 to 430 g/t), Fe (from 524 to 686 g/t), Cr (from 7.63 to 9.9 g/t), K (from 6.68 to 17.6 g/t), Sn (from 112 to 121 g/t), Ca (from 3.99 to 6.08 g/t), Ti (from 11.9 to 13.5 g/t), Ga (from 42.6 to 44.1 g/t), B (from 12.9 to 17.9 g/t), and Zn (from 6.22 to 8.74 g/t). The most contrasting change in the distribution nature is manifested for Mn, Fe, Cr, K, Sn, Ca, Ti, Ga, B, Cs, and Zn.

The alkaline element content (Li, Cs, K, Rb, Na) in spodumene from the Kolatan deposit is 39,652-45,075 g/t, on average 41,926 g/t; from the Dara-e-Pech deposit 37,286-52,289 g/t, on average 43,455 g/t; from the Tsamgal deposit 38,139-49,289 g/t, on average 43,927 g/t. The transition element content (Fe, Mg, Mn, Ca, Ti, V, Cr, Zn, Cu, Nb, Ta, Zr) in spodumene from the Kolatan deposit is from 531 to 1681 g/t, on average 1145 g/t; in spodumene from the Dara-e-Pech deposit from 177 to 5775 g/t, on average 2544 g/t; in spodumene from the Tsamgal deposit from 316 to 2863 g/t, on average 1055 g/t (Fig.7, j).

The binary correlation diagram between alkali and transition elements shows a positive correlation trend in spodumene from the greyish-white centre to the pink-violet edge (Fig.7).

It should be noted that the positive relationship between alkali and transition elements in spodumene correlates with the distance from the parent intrusion (Fig.7, j). Obviously, the consequence of the melt movement from the bottom up the section was the differentiation and fractionation of the fluid as it moved away from the parent intrusion. Zoning is also clearly manifested inside the pegmatite veins. Thus, spodumene with low contents of alkali and transition elements is found in the footwall, large transparent pinkish-violet crystals with high contents of alkali and transition elements are in the quartz core and in miarolitic voids (see Fig.2, 4).

The distribution of lithium in steeply dipping bodies is characterized by an increased concentration in spodumene of the central zone, in contrast to the selvages (see Fig.2, c). This pattern can also be used when developing lithium pegmatites in the region [49]. Here, selective development of rich ore deposits will be oriented toward the near-vertical zones in the central parts of pegmatite veins.

The regular placement of lithium-rich spodumene in the hypsometric sequence of increasing heights (see Fig.2, d) on which spodumene pegmatites lie is important. Lithium concentration in the most distant from the granite intrusion bodies is due to the high migration capacity of lithium.

Internal structure of pegmatite bodies is determined by their formation conditions, the occurrence nature, and the type of pegmatite. Large, well-mineralized voids with multi-coloured gem spodumene formed in albite-microcline and albite veins, occurring only among gabbro-diorites of the Nilaw complex. Pegmatites rich in gem varieties are found in the Dara-e-Pech and Nilaw-Kulam deposits (see Fig.2).

Conclusion

The study of spodumenes from the Kolatan, Dara-e-Pech, and Tsamgal deposits revealed intraphase heterogeneity manifested in the zoned coloration of both transparent and opaque crystals, which is associated with a change in the rare element contents. We found that light-coloured zones have a higher Fe/Mn ratio than brightly coloured ones (0.03 and 6.9 g/t, respectively).

Sn content in spodumenes collected at a great distance from the parent rocks is significantly higher compared to those located nearby. For example, the average Sn content in spodumene from the Kolatan deposit is 33.6 g/t, while in spodumene from the Digal, Gulsalak, and Tsamgal deposits it is 117-128 g/t. We should note a positive correlation between Sn and Na. For zoned spodumene from the Kolatan, Dara-e-Pech, and Tsamgal deposits, a positive correlation was observed between Na, Ti, V, Cr, Mn, Sn, Ga, and Zn. An increase in the content of these elements was noted in transparent pinkish-violet crystals of spodumene, i.e. due to the increase in the content of minor and rare elements, the mineral acquires gemstone properties. In all analysed spodumenes, an increase in the manganese content leads to an improvement in gem qualities – the appearance of a pinkish-violet colour and increased transparency. In the greyish-white zone, as well as in the crystal centre, Fe content is higher than Mn content. In the studied spodumene crystals, the transparency and colour saturation increase from the centre to the edge, the colour from greyish-white to pinkish-violet. We noted a change in the colour intensity depending on the crystallographic directions, with the deepest colours observed along the elongation axis, where the rare element contents increase.

Syngenetic intraphase heterogeneity of spodumene from the three deposits studied is the result of changes in the physical and chemical conditions of mineral formation during pegmatite evolution and is due to the isomorphic replacement of Li and Al by such trace elements as Fe, Mn, Cr, etc.

Opaque white spodumene is predominantly distributed in the hanging wall, and coarse-grained light pink and pinkish-violet is found in the block zone and in the quartz core.

Fine-crystalline acicular spodumene in an aphanitic dyke is formed in aggregates of fine tabular saccharoidal albite as a result of dissolution of early spodumene during albitization and lithium redeposition.

Among rare elements, Ga content in spodumene in microcline-spodumene-albite veins of the Dara-e-Pech deposit is consistently higher than in spodumene from lepidolite-clevelandite-spodumene veins of the Kolatan and Tsamgal deposits. This is due to the difference in the composition of the host rocks at these deposits. Pegmatite veins of the Kolatan and Tsamgal deposits are found among weakly metamorphosed phyllitic schists. Pegmatite veins at the Dara-e-Pech deposit occur among granodiorites. Transparent gem-quality spodumene with high gallium content is found in pegmatite bodies occurring among biotite-amphibole diorites and gabbro-diorites of the Nilaw complex, Dara-e-Pech and Nilaw-Kulam deposits. It crystallized in a relatively calm, tectonically stable environment.

In general, pegmatite bodies occurring in gabbro-diorite massifs of the Nilaw complex have, in comparison with pegmatite bodies from phyllitic schists, all other things being equal (degree of melt mineralization and occurrence nature of pegmatite veins), more distinct zoning and larger grain and block sizes of individual minerals, which is associated with pegmatite bodies morphology and more stable conditions of pegmatite melt crystallization.

A distinct differentiation of lithium content is observed in pegmatite occurring at different hypsometric levels and at different distances from the granitoid massif. The most remote and overlying of them contain spodumene with maximum lithium concentration, which is possibly due to its increased migration capacity in the residual pegmatite melt.

Geochemical criteria for separating magmatic and hydrothermal spodumene are based on the analysis of homogeneity and heterogeneity of compositions in different zones of spodumene crystals. In the central part of all analysed samples, a homogeneous composition formed by the initial stable melt is observed in comparison with the peripheral zones. The spodumene pegmatite-forming melt appeared as a result of multistage fractional crystallization of lithium-bearing leucogranite magma of phase III of the Laghman complex. The distinct zoning of spodumene crystals is associated with changes in the fluid composition as part of crystal growth during magmatic fractionation and transition to the hydrothermal stage. The peripheral zones of crystals are marked by different individual growth zones caused by a change in fluids, the mobility of which suggests variability of their compositions.

References

- Krivolapova O.N., Fureev I.L. Application of microwave radiation for decrepitation of spodumene from the Kolmozerskoe deposit. Izvestiya. Non-Ferrous Metallurgy. 2023. Vol. 29. N 6, p. 5-12. DOI: 10.17073/0021-3438-2023-6-5-12

- Gabriel A., Slavin M., Carl H.F. Minor constituents in spodumene. Economic Geology. 1942. Vol. 37. Iss. 2, p. 116-125. DOI: 10.2113/gsecongeo.37.2.116

- Bibienne T., Magnan J.-F., Rupp A., Laroche N. From Mine to Mind and Mobiles: Society’s Increasing Dependence on Lithium. Elements. 2020. Vol. 16. N 4, p. 265-270. DOI: 10.2138/gselements.16.4.265

- Resentera A.C., Rosales G.D., Esquivel M.R., Rodriguez M.H. Thermal and structural analysis of the reaction pathways of α-spodumene with NH4HF2. Thermochimica Acta. 2020. Vol. 689. N 178609. DOI: 10.1016/j.tca.2020.178609

- Singh Y. Lithium Potential of the Indian Granitic Pegmatites. Journal of the Geological Society of India. 2022. Vol. 98. N 7, p. 917-925. DOI: 10.1007/s12594-022-2095-x

- Gourcerol B., Gloaguen E., Melleton J. et al. Re-assessing the European lithium resource potential – A review of hard-rock resources and metallogeny. Ore Geology Reviews. 2019. Vol. 109, p. 494-519. DOI: 10.1016/j.oregeorev.2019.04.015

- Li Chen, Nannan Zhang, Tongyang Zhao et al. Lithium-Bearing Pegmatite Identification, Based on Spectral Analysis and Machine Learning: A Case Study of the Dahongliutan Area, NW China. Remote Sensing. 2023. Vol. 15. Iss. 2. N 493. DOI: 10.3390/rs15020493

- Müller A., Reimer W., Wall F. et al. GREENPEG – exploration for pegmatite minerals to feed the energy transition: first steps towards the Green Stone Age. Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 2023. Vol. 526, p. 193-218. DOI: 10.1144/SP526-2021-189

- Nuernberg R.B., Faller C.A., Montedo O.R.K. Crystallization kinetic and thermal and electrical properties of β-spodumeness/cordierite glass-ceramics. Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry. 2017. Vol. 127. Iss. 1, p. 355-362. DOI: 10.1007/s10973-016-5397-7

- Peng Xing, Chengyan Wang, Lei Zeng et al. Lithium Extraction and Hydroxysodalite Zeolite Synthesis by Hydrothermal Conversion of α-Spodumene. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering. 2019. Vol. 7. Iss. 10, p. 9498-9505. DOI: 10.1021/acssuschemeng.9b00923

- Ferraz R.F., Sousa J.F., Lima H.R.B.R., Oliveira R.A.P. Structural and Morphological Characterization of the Chromium-doped β-Spodumene to Ceramic Pigment. Brazilian Journal of Radiation Sciences. 2022. Vol. 10. N 2A, p. 15. DOI: 10.15392/bjrs.v10i2A.1772

- Kavanagh L., Keohane J., Garcia Cabellos G. et al. Global Lithium Sources – Industrial Use and Future in the Electric Vehicle Industry: A Review. Resources. 2018. Vol. 7. Iss. 3. N 57. DOI: 10.3390/resources7030057

- Dessemond C., Lajoie-Leroux F., Soucy G. et al. Spodumene: The Lithium Market, Resources and Processes. Minerals. 2019. Vol. 9. Iss. 6. N 334. DOI: 10.3390/min9060334

- Claffy E.W. Composition, tenebrescence and luminescence of spodumene minerals. American Mineralogist. 1953. Vol. 38. N 11-12, p. 919-931.

- Abdullah A.A., Oskierski H.C., Altarawneh M. et al. Phase transformation mechanism of spodumene during its calcination. Minerals Engineering. 2019. Vol. 140. N 105883. DOI: 10.1016/j.mineng.2019.105883

- Dessemond C., Soucy G., Harvey J.P., Ouzilleau P. Phase Transitions in the α-γ-β Spodumene Thermodynamic System and Impact of γ-Spodumene on the Efficiency of Lithium Extraction by Acid Leaching. Minerals. 2020. Vol. 10. Iss. 6. N 519. DOI: 10.3390/min10060519

- Salakjani N.Kh., Singh P., Nikoloski A.N. Mineralogical transformations of spodumene concentrate from Greenbushes, Western Australia. Part 1: Conventional heating. Minerals Engineering. 2016. Vol. 98, p. 71-79. DOI: 10.1016/j.mineng.2016.07.018

- Mashkoor R., Ahmadi H., Rahmani A.B., Pekkan E. Detecting Li-bearing pegmatites using geospatial technology: the case of SW Konar Province, Eastern Afghanistan. Geocarto International. 2022. Vol. 37. Iss. 26, p. 14105-14126. DOI: 10.1080/10106049.2022.2086633

- Evdokimov A.N., Yosufzai A. Geological Position of Rare-Metal Pegmatites of the Laghman Granitoid Complex, Afghanistan. Russian Journal of Earth Sciences. 2025. Vol. 25. Iss. 1. N ES1002 (in Russian). DOI: 10.2205/2025ES000998

- Rossovskiy L.N., Chmyrev V.M. Distribution patterns of rare-metal pegmatites in the Hindu Kush (Afghanistan). International Geology Review. 1977. Vol. 19. Iss. 5, p. 511-520. DOI: 10.1080/00206817709471047

- Rossovskiy L.N., Konovalenko S.I. Features of the formation of the rare-metal pegmatites under conditions of compression and tension (as exemplified by the Hindu Kush region). International Geology Review. 1979. Vol. 21. Iss. 7, p. 755-764. DOI: 10.1080/00206818209467116

- Wesełucha-Birczyńska A., Słowakiewicz M., Natkaniec-Nowak L., Proniewicz L.M. Raman microspectroscopy of organic inclusions in spodumenes from Nilaw (Nuristan, Afghanistan). Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy. 2011. Vol. 79. Iss. 4, p. 789-796. DOI: 10.1016/j.saa.2010.08.054

- Rehman H.U., Martens G., Ying Lai Tsai et al. An X-ray Absorption Near-Edge Structure (XANES) Study on the Oxidation State of Chromophores in Natural Kunzite Samples from Nuristan, Afghanistan. Minerals. 2020. Vol. 10. Iss. 5. N 463. DOI: 10.3390/min10050463

- London D. The origin of primary textures in granitic pegmatites. The Canadian Mineralogist. 2009. Vol. 47. N 4, p. 697-724. DOI: 10.3749/canmin.47.4.697

- Sirbescu M.-L.C., Schmidt C., Veksler I.V. et al. Experimental Crystallization of Undercooled Felsic Liquids: Generation of Pegmatitic Texture. Journal of Petrology. 2017. Vol. 58. Iss. 3, p. 539-568. DOI: 10.1093/petrology/egx027

- Phelps P.R., Lee C.T.A., Morton D.M. Episodes of fast crystal growth in pegmatites. Nature Communications. 2020. Vol. 11. N 4986. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-020-18806-w

- Sirbescu M.-L.C., Doran K., Konieczka V.A. et al. Trace element geochemistry of spodumene megacrystals: A combined portable-XRF and micro-XRF study. Chemical Geology. 2023. Vol. 621. N 121371. DOI: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2023.121371

- Anderson A.J. Microthermometric behavior of crystal-rich inclusions in spodumene under confining pressure. The Canadian Mineralogist. 2019. Vol. 57. N 6, p. 853-865. DOI: 10.3749/canmin.1900013

- Morozova L.N., Bazai A.V. Spodumene from rare-metal pegmatites of the Kolmozerskoe lithium deposit (Kola Peninsula). Zapiski Rossiiskogo mineralogicheskogo obshchestva. 2019. Vol. 148. N 1, p. 65-78 (in Russian). DOI: 10.30695/zrmo/2019.1481.06

- Akbarpuran Haiyati S.A., Gulbin Yu.L., Sirotkin A.N., Gembitskaya I.M. Compositional Evolution of REE- and Ti-Bearing Accessory Minerals in Metamorphic Schists of Atomfjella Series, Western Ny Friesland, Svalbard and Its Petrogenetic Significance. Geology of Ore Deposits. 2021. Vol. 63. № 7. P. 634-653. DOI: 10.1134/S1075701521070047

- Skublov S.G., Yosufzai A., Evdokimov A.N., Gavrilchik A.K. Trace element composition of beryl from spodumene pegmatite deposits of the Kunar Province, Afghanistan. Mineralogy. 2024. Vol. 10. N 2, p. 58-77 (in Russian). DOI: 10.35597/2313-545X-2024-10-2-4

- Rossovskiy L.N., Chmyrev V.M., Salakh A.S. New fields and belts of rare-metal pegmatites in the Hindu Kush (Eastern Afghanistan). International Geology Review. 1976. Vol. 18. Iss. 11, p. 1339-1342. DOI: 10.1080/00206817609471351

- Skublov S.G., Hamdard N., Ivanov M.A., Stativko V.S. Trace element zoning of colorless beryl from spodumene pegmatites of Pashki deposit (Nuristan province, Afghanistan). Frontiers in Earth Science. 2024. Vol. 12. N 1432222. DOI: 10.3389/feart.2024.1432222

- Levashova E.V., Skublov S.G., Hamdard N. et al. Geochemistry of Zircon from Pegmatite-bearing Leucogranites of the Laghman Complex, Nuristan Province, Afghanistan. Russian Journal of Earth Sciences. 2024. Vol. 24. Iss. 2. N ES2011. DOI: 10.2205/2024ES000916

- Beskin S.M., Marin Yu.B. Granite Systems with Rare-Metal Pegmatites. Geology of Ore Deposits. 2020. Vol. 62. N 7, p. 554-563. DOI: 10.1134/S107570152007003X

- Alekseev V.I., Alekseev I.V. The Presence of Wodginite in Lithium – Fluorine Granites as an Indicator of Tantalum and Tin Mineralization: A Study of Abu Dabbab and Nuweibi Massifs (Egypt). Minerals. 2023. Vol. 13. Iss. 11. N 1447. DOI: 10.3390/min13111447

- Zakharova A.A., Voytekhovsky Yu.L., Kompanchenko A.A., Neradovsky Yu.N. Methodology for determination of petrographic structures using the MIU-5M device. Vestnik of MSTU. 2022. Vol. 25, N 1, p. 5-11 (in Russian). DOI: 10.21443/1560-9278-2022-5-11

- Voytekhovsky Yu.L., Zakharova A.A. Petrographic structures: Khibiny ijolites and urtites. Vestnik of MSTU. 2021. Vol. 24. N 2, p. 160-167 (in Russian). DOI: 10.21443/1560-9278-2021-24-2-160-167

- Thomas R., Davidson P., Beurlen H. Tantalite-(Mn) from the Borborema Pegmatite Province, northeastern Brazil: conditions of formation and melt- and fluid-inclusion constraints on experimental studies. Mineralium Deposita. 2011. Vol. 46. Iss. 7, p. 749-759. DOI: 10.1007/s00126-011-0344-9

- Skublov S.G., Gavrilchik A.K., Berezin A.V. Geochemistry of beryl varieties: comparative analysis and visualization of analytical data by principal component analysis (PCA) and t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE). Journal of Mining Institute. 2022. Vol. 255, p. 455-469. DOI: 10.31897/PMI.2022.40

- Skublov S.G., Levashova E.V., Mamykina M.E. et al. The polyphase Belokurikhinsky granite massif, Gorny Altai: isotope-geochemical study of zircon. Journal of Mining Institute. 2024. Vol. 268, p. 552-575.

- Skublov S.G., Petrov D.A., Galankina O.L. et al. Th-Rich Zircon from a Pegmatite Vein Hosted in the Wiborg Rapakivi Granite Massif. Geosciences. 2023. Vol. 13. Iss. 12. N 362. DOI: 10.3390/geosciences13120362

- Czaja M., Lisiecki R., Kądziołka-Gaweł M., Winiarski A. Some Complementary Data about the Spectroscopic Properties of Manganese Ions in Spodumene Crystals. Minerals. 2020. Vol. 10. Iss. 6. N 554. DOI: 10.3390/min10060554

- Duan Yonghua, Ma Lishi, Li Ping, Cao Yong. First-principles calculations of electronic structures and optical, phononic, and thermodynamic properties of monoclinic α-spodumene. Ceramics International. 2017. Vol. 43. Iss. 8. p. 6312-6321. DOI: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2017.02.038

- Morozova L.N., Sokolova E.N., Smirnov S.Z. et al. Spodumene from rare-metal pegmatites of the Kolmozero lithium world-class deposit on the Fennoscandian shield: trace elements and crystal-rich fluid inclusions. Mineralogical Magazine. 2021. Vol. 85. Iss. 2, p. 149-160. DOI: 10.1180/mgm.2020.104

- Jia-Min Wang, Kang-Shi Hou, Lei Yang et al. Mineralogy, petrology and P-T conditions of the spodumene pegmatites and surrounding meta-sediments in Lhozhag, eastern Himalaya. Lithos. 2023. Vol. 456-457. N 107295. DOI: 10.1016/j.lithos.2023.107295

- Ginzburg A.I. Spodumene and the processes of its alteration. Trudy Mineralogicheskogo muzeya. 1959. Iss. 9, p. 19-52 (in Russian).

- Ito A.S., Isotani S. Heating effects on the optical absorption spectra of irradiated, natural spodumene. Radiation Effects and Defects in Solids. 1991. Vol. 116. Iss. 4, p. 307-314. DOI: 10.1080/10420159108220737

- Alekseev V.I., Marin Yu.B. Accessory Cassiterite as an Indicator of Rare Metal Petrogenesis and Mineralization. Geology of Ore Deposits. 2022. Vol. 64. N 7, p. 397-423. DOI: 10.1134/S1075701522070029