New source of noble corundum in Kenya

- 1 — Ph.D. Assistant Professor Saint-Petersburg State Mining Institute (Technical University)

- 2 — President of Company Kennedy International Ltd

- 3 — Geologist of 1st category All-Russian State Research Geological Institute

Abstract

The large-scale occurrence of ruby and sapphire in Kenya is represented by contemporary river-bed and valley alluvial placers. The first ones are characterized by a high content of ruby (up to 10,4 ct/m3), the second type is interesting due to the amount of forecasted resources: up to 2,3 million ct of ruby and 1,2 million ct of sapphire. It turned out to trace the mechanism of corundum concentrations forming, the mineral crystallized in Archean high-alumina gneisses affected by Precambrian basites (ultrabasites), and then survived a complicated way: – ancient eluvium – ancient alluvium – transportation by basaltic Pleistocenic magma – Holocenic weathering crust of volcanites – talus – contemporary alluvium.

The market for jewelry varieties of corundum, which include ruby and the less valuable numerous varieties of sapphire, is based on high-quality raw materials from a very limited number of countries. For ruby, these are, first and foremost, Myanmar (Mogok), followed by Thailand, Cambodia, Sri Lanka, Afghanistan, Vietnam, Tanzania, and Kenya. For sapphire, this list is headed by India (Kashmir) and Myanmar (Mogok) and continued by Thailand, Cambodia, Sri Lanka, Australia, China, Vietnam, USA (Montana), Nigeria, and Tanzania. Thus, for Kenya and neighboring Tanzania, noble corundums are a raw material that is, to a certain extent, traditional.

In four regions of Kenya, five occurrences (deposits and showings) with rubies are known, two of which also contain sapphires, and another eight showings containing only sapphires. In neighboring Tanzania, which, largely due to the development of unique tanzanite and tsavorite deposits, has a higher level of development in the jewelry raw material industry, there are already 25 ruby occurrences (four of them with sapphires) and six sapphire ones. Tanzanian sapphires have fancy colors, i.e., not red and not blue. Pink and purple stones predominate, padparadscha is found, as well as sapphires with color reversal [2]. Several Tanzanian deposits are located near the border with Kenya.

The geology and genesis of noble corundum deposits in Kenya are extremely poorly covered in the literature. The most important primary ruby deposits – Penny Lane and John Saul – are located in Precambrian rocks in the southern part of Tsavo West National Park. According to [2], in the first case, rubies are located in tremolite-actinolite-talc-chlorite rocks of desilicated veins cutting altered serpentinized ultrabasites, and in the second – in the contact zone of a small intrusion of serpentinized ultrabasites and plumeazite pegmatites.

In 2005, in Kenya, a significant in area showing of noble corundums in placers on the slopes of a Quaternary volcano was discovered accidentally, i.e., without geological exploration. In August 2007, the authors carried out a number of geological traverses on the Kennedy area and conducted sampling. The first results of the geological studies of the showing are considered noteworthy.

The Kennedy showing is located in the south of the country, outside known corundum-bearing fields. The relief of the area is characterized by the presence of a ridge of low hills of volcanic origin in its center and a relatively low-angler foothill area composed of weathered Archean metamorphic rocks. The Kennedy area has an elevation difference within 410 m. The slopes of the volcanic ridge in its axial part are relatively steep (in places up to 30°), but on the periphery of the volcano they flatten out (to a few degrees). These slopes are noticeably asymmetrical: the eastern ones are steeper, and the western ones are relatively low-angle. From the south, the area is bounded by a river, into which temporary watercourses (streams and small rivers) flow, crossing the western, southern, and eastern slopes of the volcano.

The area of the showing was studied in sufficient detail by the country’s geological service during 1:125,000 scale mapping in 1956-1957. Nevertheless, in the geological description of the area compiled from its results [3], rubies and sapphires in this territory were not mentioned.

The area is characterized by a two-tiered structure. The foundation of the territory is composed of complexly dislocated Archean rocks, metamorphosed under conditions reaching granulite facies metamorphism. They are intruded by small Precambrian intrusions of acid, basic, and ultrabasic composition. On the surface of the Archean sequence, leveled in Late Cretaceous – pre-Miocene time, lie the rocks of the upper structural tier – multiphase sheets and cones of Pleistocene basic volcanic rocks, belonging to both the normal (olivine basalts) and alkaline petrochemical series (analcime basanites) [3].

Directly within the territory of the Kennedy showing, the Archean package of metamorphic rocks, including various gneisses, as well as para-amphibolites and plagioclase amphibolites, is folded into an anticline with relatively steeply dipping limbs (50-65°) and a hinge plunging to the north-northeast. An extinct volcano is located on the metamorphic rocks, with five low-angle cones lying on a line oriented in a north-northwest direction. The length of the volcanic rock body in plan is 5 km, the width is 2.5 km. The vertical thickness of the volcanic edifice is about 200 m.

According to our data, the volcano was formed only by lava of basic composition of the normal petrochemical series. Its body is composed mainly of pyroclastic rocks: agglomerate tuffs, tuff lavas, and ignimbrites, interbedded with olivine basalts. The thickness of individual olivine-basalt flows ranges from 2 to 20 m, while the thickness of pyroclastic rock layers reaches 50 m. The chemical composition of the olivine basalts is shown in Table 1. For comparison, an analysis of analcime basanites outcropping to the southwest of the area is given.

In a number of cases, in stream beds, it was possible to observe the contact of volcanic rocks with the underlying Archean sequence: alluvial deposits with pebbles and gravel of these rocks were found on the metamorphic rocks. The assumption of lava pouring into a river channel was confirmed by the discovery of distinct spheroidal parting in the lower layer of basalts in one of the outcrops.

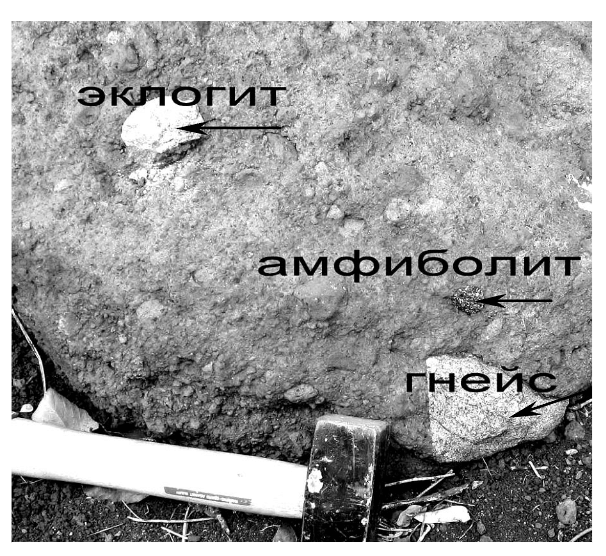

The volcanites are characterized by the widespread occurrence of xenoliths of basement rocks – variously rounded fragments of gneisses, amphibolites, altered basic-ultrabasic rocks, and vein quartz (Fig. 1). It is important that finds of corundum in the deluvium are most frequent in places where rounded pebbles of these Archean rocks accumulate in it.

The altered basic-ultrabasic rocks have been studied preliminarily. They represent variably metamorphosed, mostly melanocratic gabbro, melanocratic gabbro-norite, as well as pyroxenites, in some cases containing green spinel (hercynite?, up to 15%). The development of brown reaction rims, consisting mainly of iron hydroxides (?) and magnetite in association with other secondary minerals, including colorless corundum and ruby (up to 3%), is extremely characteristic.

The rims envelop grains of monoclinic pyroxene and spinel. It can be assumed that at least part of the rubies in the area could have formed by replacement of chromian hercynite during the metamorphism of these rocks.

Table 1

Chemical composition of rocks in the Kennedy manifestation area, % by weight

|

Component |

Sample number |

|||||||||

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

|

|

SiO2 |

41.80 |

45.57 |

48.10 |

53.60 |

46.70 |

47.80 |

46.70 |

47.85 |

48.60 |

48.60 |

|

Al2O3 |

9.34 |

10.50 |

17.20 |

21.90 |

18.90 |

19.10 |

18.10 |

11.60 |

15.80 |

16.40 |

|

Fe2O3 |

13.80 |

2.40 |

7.60 |

6.39 |

7.20 |

6.74 |

8.40 |

9.40 |

6.30 |

4.84 |

|

Cr2O3 |

0.061 |

N.d. |

0.090 |

0.022 |

0.083 |

0.171 |

0.091 |

0.075 |

0.057 |

0.051 |

|

FeO |

N.d. |

10.15 |

N.d. |

N.d. |

N.d. |

N.d. |

N.d. |

N.d. |

N.d. |

N.d. |

|

MgO |

10.1 |

10.85 |

10.5 |

5.90 |

12.50 |

5.80 |

12.00 |

15.90 |

9.70 |

7.50 |

|

CaO |

9.20 |

12.16 |

8.80 |

8.80 |

8.80 |

11.4 |

8.40 |

8.30 |

9.50 |

11.30 |

|

Na2O |

0.10 |

3.46 |

1.08 |

2.38 |

1.39 |

2.26 |

1.23 |

0.08 |

2.09 |

2.50 |

|

K2O |

0.27 |

0.90 |

0.25 |

0.24 |

0.12 |

0.29 |

0.12 |

0.08 |

0.13 |

0.17 |

|

H2O + |

N.d. |

0.76 |

N.d. |

N.d. |

N.d. |

N.d. |

N.d. |

N.d. |

N.d. |

N.d. |

|

H2O |

N.d. |

0.40 |

N.d. |

N.d. |

N.d. |

N.d. |

N.d. |

N.d. |

N.d. |

N.d. |

|

TiO2 |

6.82 |

2.72 |

0.22 |

0.14 |

0.09 |

0.44 |

0.08 |

0.18 |

0.06 |

Tr. |

|

P2O5 |

N.d. |

0.45 |

N.d. |

N.d. |

N.d. |

N.d. |

N.d. |

N.d. |

N.d. |

N.d. |

|

MnO |

0.20 |

0.09 |

0.15 |

0.09 |

0.12 |

0.13 |

0.13 |

0.19 |

0.12 |

0.13 |

|

CO2 |

N.d. |

0.09 |

N.d. |

N.d. |

N.d. |

N.d. |

N.d. |

N.d. |

N.d. |

N.d. |

|

LoI |

10.1 |

N.d. |

2.02 |

2.16 |

1.61 |

3.15 |

1.9 |

6.42 |

7.70 |

8.56 |

|

Total |

101.79 |

100.5 |

96.01 |

101.62 |

97.51 |

97.28 |

97.15 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

Note. N.d. – not determined; Tr. – traces. Samples: 1 – olivine basalt of the Kennedy site; 2 – basanites of the area [3]; 3-10 – modified basic-ultrabasic rocks. The analyses of samples 1, 3-10 were performed in the laboratory of the Mining and Geological Department of the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources of Kenya and are being published for the first time.

The modern weathering crust on the volcanic rocks is represented only by a disintegration zone and has developed to a depth of merely 0.3-0.5 m because, firstly, the young (Pleistocene) age of the volcanic rocks did not allow the weathering process to act over a long period, and secondly, the weathering products on the relatively steep slopes of the central part of the volcano are intensively washed down to its periphery during the rainy seasons, where they form a layer of deluvium and colluvium. It is noticeable that porous pyroclastic rocks weather significantly more intensively than the less permeable basalts, which stand out as low remnants.

Due to strong sheet erosion, the thickness of the deluvium on the slopes of the central part of the volcano is also small and is no more than 0.2 m. It increases on the low-angle surfaces of the volcano’s peripheral zone, where its value reaches 2 m.

Alluvial deposits in the Kennedy area differ noticeably from each other under different landscape conditions, which determines their differing potential for accumulating placers with significant reserves. In the upper part of the volcanic cone, in barely pronounced gullies, the distribution of alluvium, both laterally and vertically, is very insignificant. In these young gullies, it is practically indistinguishable from deluvium and has a small thickness (up to 0.2 m). On the middle part of the volcano’s slope, in the channels of temporary streams on relatively steep slopes, heterogeneous-grained (from boulders to coarse sand) alluvial deposits lie in shallow U- or V-shaped troughs. As the slope decreases over sections tens of meters long, the width of the channel deposits sometimes increases to 10 m. The thickness of the alluvium here reaches 1.5 m. Importantly, during the rainy seasons, the alluvium in this part of the volcano is very dynamically moved downstream and intensively renewed. Finally, in the low-angle part of the area, in the valleys of temporary rivers, the alluvium has the greatest thickness. Here, the width of the valley deposits laterally in places exceeds 80 m, and the thickness reaches 3 m.

Fragments of jewelry rubies and sapphires are sporadically collected from the rain-washed surface of the deluvium or extracted by manual panning, usually from the alluvium of small temporary watercourses on the middle parts of the slopes. The zone of frequent ruby finds in the deluvium almost completely encircles the largest of its cones like a ring, where the slopes are not flattened and the deluvium is intensively washed during the rainy season. The collection of noble corundums is somewhat more successful on the eastern, steeper slope, where the deluvium is more mobile. Over the rest of the low-angle area of the volcano, finds are rarer, despite the significant thickness of the deluvium. The relatively even distribution of jewelry stones across the volcano’s area suggests that corundums enter the loose deposits from the main volcanic rocks – agglomerates and basalts – and not from any locally distributed epigenetic formations.

In the alluvium of the middle slopes, finds of rubies and sapphires occur predominantly on the west and south of the volcano near the most powerful deluvial deposits. Artisanal mining is carried out in trough-shaped channels of temporary streams or in “pools” – depressions in the channel under small waterfalls. Sampling results for rubies in such deposits (Table 2) showed that the weighted average (per sample volume) ruby content in the channel alluvium was 2.43 ct/m³

Table 2

The results of testing of channel alluvium in the middle part of the slopes of the volcano

|

Observation point |

Total weight of rubies, ct |

Sample volume, m3 |

Ruby content, ct/m3 |

|

14, “pool” |

0.15 |

0.14 |

1.07 |

|

57, “pool” |

1.56 |

1.5 |

1.04 |

|

15-20 m above the observation point 57 |

0.94 |

0.2 |

4.70 |

|

73, a young stream on a powerful gently sloping deluvium |

0.56 |

0.5 |

1.12 |

|

74, same |

– |

0.6 |

– |

|

77, “ “ |

1.22 |

0.55 |

2.22 |

|

76, “ “ |

6.24 |

0.6 |

10.40 |

|

79, “ “ |

0.59 |

0.7 |

1.41 |

Fig.1. Xenoliths of basement rocks in the Kennedy site agglomerate

Fig.2. Rubies from quaternary sediments of the Kennedy site (Gemstone International Mining Ltd. collection). Large stones look dark due to cracks.

Fig. 3. Ruby (dark), replacing distene (light). Deluvium pebbles from the volcano slope (Gemstone International Mining Ltd collection)м

Fig. 4. Ruby crystals from the alluvium of a river flowing through Archean metamorphites outside the Kennedy site (Gemstone International Mining Ltd. collection)

Among the found corundums, approximately half are rubies. The remainder is represented by sapphires and grey corundums. Both rubies and sapphires are always found as rounded fragments of crystals or their pieces – initially rounded and then re-fractured – which indicates very prolonged transport. An idea of the fragment shapes can be obtained from Fig. 2. Relatively large stones contain cracks and “curtains,” but after splitting or sawing, they yield blocks suitable for faceting.

Rubies are more often transparent and have a saturated red color with a slight violet hue, i.e., a color typical of the best Burmese rubies. It varies little from sample to sample. The average weight of stones in the Gemstone International Mining Ltd collection is 1.72 carats. The largest monoblocks allow for faceted stones weighing up to 2.1 carats.

Sapphires are found as translucent or less frequently transparent rounded fragments. Among sapphires, there is a great diversity of colors – from violet, lilac, pinkish-violet, orange, brownish-orange to grey and even black. Blue sapphires were not encountered. The average weight of facet-quality sapphire fragments is somewhat higher than that of rubies – 2.83 carats. The color of the rounded black sapphire fragments is caused by microscopic inclusions of hematite. Inside the black sapphire samples, plate-like zones of light violet sapphire 0.8-1.5 mm thick are visible within the fragments.

Among rare finds are noted rounded fragments of aggregates consisting of small tabular ruby crystals up to 2 mm in diameter intergrown with magnetite individuals and iron hydroxide crusts, as well as rounded fragments of blue kyanite crystals up to 2 1 0.5 cm in size, corroded by tabular ruby crystals up to 4 mm in diameter (Fig. 3).

The prognostic assessment of the largest (valley) placers in the Kennedy area yielded 2.3 million carats of rubies (by categories P1 + P2) and 1.2 million carats of sapphires (by category P2).

The task of detecting zones of corundum concentration in the Kennedy area is inextricably linked to the problem of their genesis. When considering the hypothesis of crystallization in basic magma, several contradictions arise:

- Known magmatic deposits of jewelry corundum worldwide are associated with eruptions of alkaline basalts, yet the alkalinity of the basalts in the Kennedy area is low (K₂O + Na₂O = 0.37%, Table 1).

- Deposits of jewelry corundum in alkaline basalts usually contain only sapphire, not ruby, as in our case.

- In the placers on the volcano’s slopes, despite the short assumed transport distance (tens to first hundreds of meters), not whole corundum crystals are found, but their fragments, and almost always preliminarily rounded.

- The magmatic hypothesis does not explain the finds on the slope of the basaltic volcano of the mentioned aggregates, recording the replacement of giant-grained kyanite by ruby (Fig. 3).

The last fact allows us to suggest that ruby was formed by a metasomatic process replacing kyanite in Archean sillimanite-muscovite or sillimanite-garnet-biotite gneisses under the influence of Precambrian basic or ultrabasic injections, which enriched the corundum with chromium. This assumption is supported by the fact that precisely in such a geological setting, several kilometers from the Kennedy area in a zone of development of high-alumina gneisses in contact with amphibolites and metagabbro, large, practically unrounded ruby crystals of good preservation were encountered in alluvium (Fig. 4).

Subsequently, the corundum crystals were liberated from the metamorphic rocks due to ancient weathering, rounded and fragmented during transport in a river flow, and concentrated in an alluvial placer. It is quite probable that the paleo-river that formed this placer extended along a north-northeast trending fault, along which the effusion of the Kennedy area basalts occurred later and on which the five volcano cones are located. This fits perfectly with both the finds of alluvial deposits at the base of the volcanites and with the spheroidal parting of the latter. Then, the corundums, together with other alluvial material, were uplifted by the lava into the layers of the volcanic edifice (see Fig. 1). Modern weathering has once again liberated the corundum fragments and allowed them to be secondarily concentrated in the deluvium and alluvium on the volcano’s slopes.

Such a transport mechanism for rubies is proposed for Kenyan deposits for the first time. However, in world geological literature, a similar transport scheme by a volcano was suggested as one of the hypotheses for several jewelry corundum deposits: on the northeastern edge of the Little Belt Mountains (Montana, USA), as well as Pailin and Bo Keo in Cambodia, Kanburi and Bo Ploy in Thailand. As for the primary origin of rubies, a genetic analogue for the Kennedy area can be considered the Cowee Creek deposits in the northeastern part of Macon County (North Carolina, USA). Similar primary sources of rubies are assumed for placers in Sri Lanka, Madagascar, Tanzania, Finland [1], and Cambodia [4].

From global practice, it is known that ruby from regional-metamorphic sequences is of industrial interest only in the case of it forming alluvial placers [1]. In the Kennedy area, volcanic transport rather served as a diluting factor for the ancient alluvial placer. In this situation, the greatest industrial interest is probably presented by the alluvial placers near the primary ruby sources in the metamorphic rocks. Their prognosis and search constitute the main task of the next stage of work.

Kenyan rubies have appeared on the market quite a long time ago and are in the same price group as stones from Thailand, Cambodia, Sri Lanka, Afghanistan, Vietnam, and Tanzania [2]. Therefore, it can be hoped that in the case of rubies from a new Kenyan deposit appearing on the market, the world jewelry market will accept them quite favorably.

The research was carried out on the initiative and with the financial support of LLC Sokolov (Russia) and Gemstone International Mining Ltd (Kenya), to whose leaders the authors express their immense gratitude.

References

- Kievlenko E.Ya. Geology of deposits of jewels / E.Ya.Kievlenko, N.N.Senkevich, A.P.Gavrilov. 2-nd ed. Moscow: Nedra, 1982, 279 p.

- Haghes R.W. Ruby & Sapphire / RWH publishing Boulder. Colorado. USA. 1997. 512 p.

- Saggerson Е.P. Geology of the Simba – Kibwezi area / Ministry of Commerce and Industry, geological survey of Kenya. Rep. № 58. 1963. 70 p.

- Saurin E. Some gem occurrences in Cambodia // Rocks & Miner. 1957. Vol.32, № 7-8, pp.397-398.